Access to Landscape Finance for Small-Scale Producers and Local Communities: A Literature Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. The Challenges of Financing Small-Scale Producers, Community-Based Enterprises, and MSMEs

1.2. Objectives and Organization of the Review

- What are the challenges for inclusive integrated landscape finance as a path to resilient landscapes?

- What innovations are being used to address those challenges?

- What can be learned from successful innovations and how can these lessons be applied in the design and assessment of mechanisms for landscape finance?

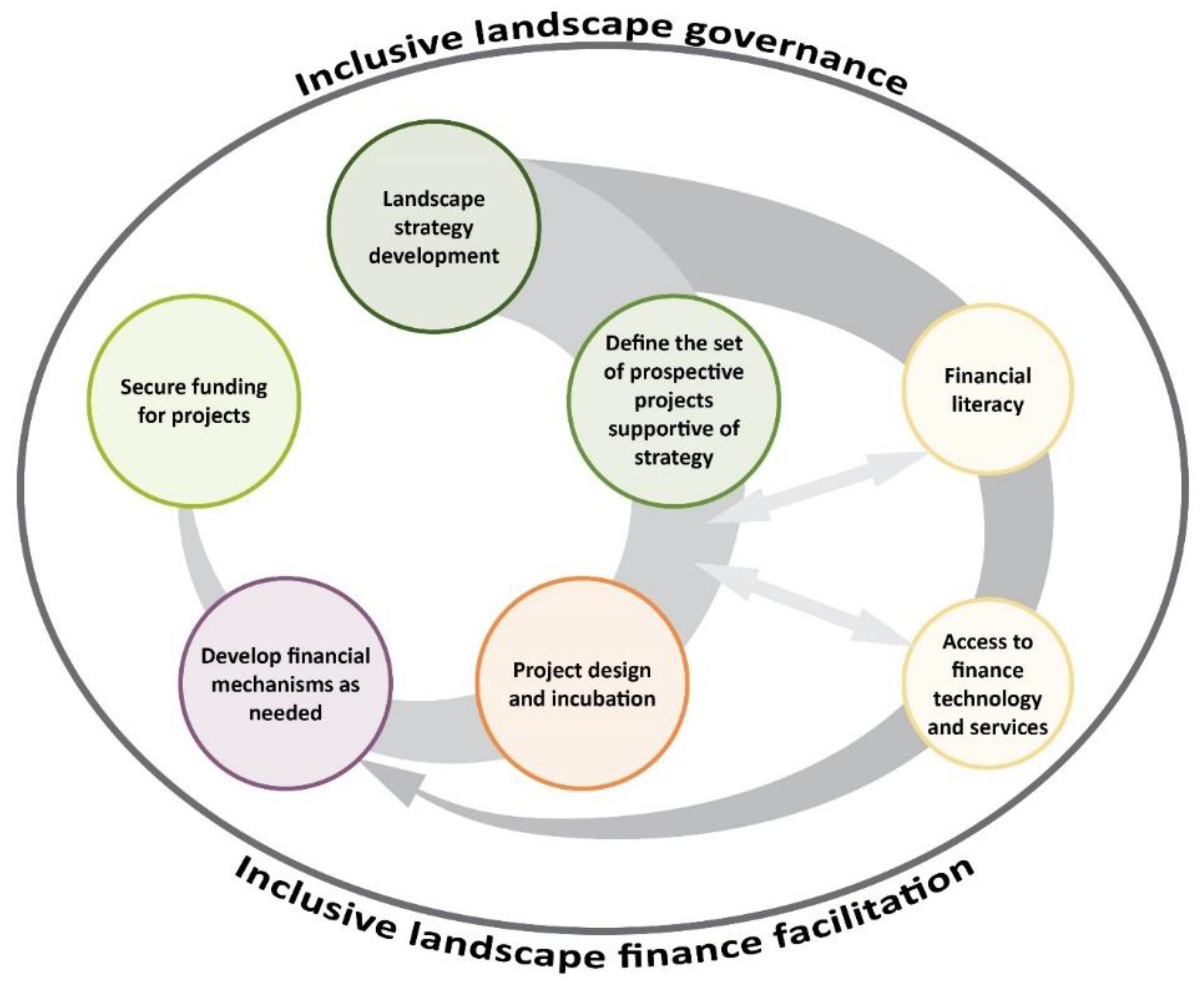

2. Integrated Landscape Finance

- Developing a strategy to meet the long-term vision of the landscape partnership’

- Defining prospective projects that support the strategy (i.e., a set of assets and enabling investments that together can transform the whole landscape);

- Designing or incubating businesses/projects or scaling key landscape investments;

- Identifying or designing finance mechanisms to support the portfolio of investments and projects and components of them;

- Securing financial resources for the landscape investment portfolio that contribute to the transformation strategy.

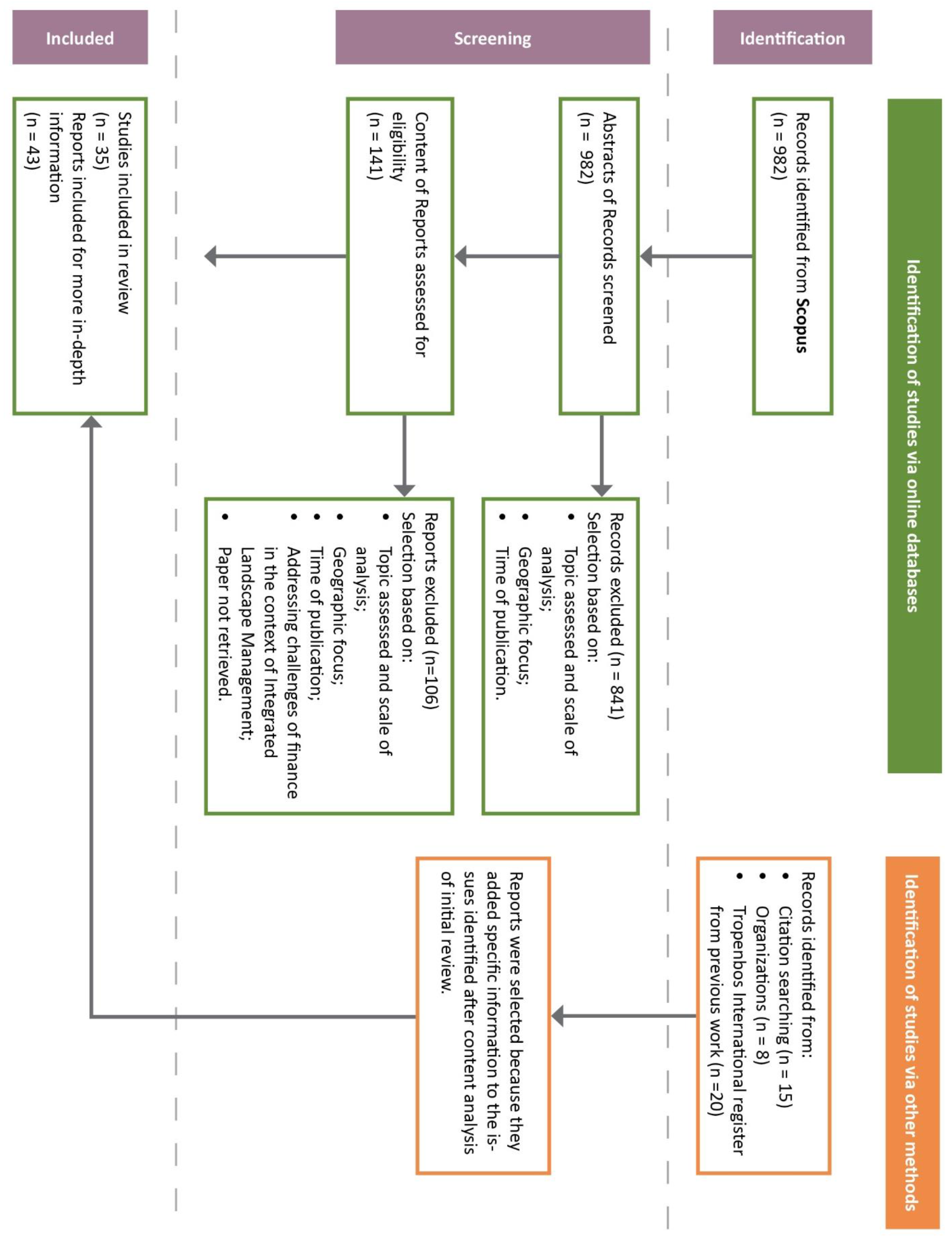

3. Methodology

- Geographic focus. Priority was given to publications that focused on the Global South. Studies carried out in other landscapes could be included in the ILR if their findings were relevant to tropical landscapes;

- Date of publication. Only studies published from 2010 onwards were considered. Exceptions could be made if the study was relevant for the ILR;

- Language. Publications had to be in English, French, or Spanish;

- Publication type. We included peer-reviewed journal articles, peer-reviewed book chapters, working/discussion papers, reports, policy briefs/ notes, and project notes.

- v.

- Topic assessed and scale of analysis. We excluded all publications that focused on finance for renewable energies, transportation, cities, and infrastructure. Scientific papers concerning finance at the household or individual level were excluded as well, as we were interested in exploring finance at the landscape scale;

- General study details (i.e., author(s), title, year of publication, academic journal, and database);

- Study methodology (i.e., database, publication type, data collection type, sample size, data analysis, robustness of methodology, geographic focus, country, case study, general focus, specific focus on landscape, specific focus on finance);

- Challenges for and factors in success (i.e., governance and institutions hampering positive outcomes, contextual factors hampering positive outcomes, any other challenges, trade-offs, specific financial gaps, governance and institutions fostering positive outcomes, contextual factors fostering positive outcomes, any other enabling factors, and synergies);

- Quality assessment. The quality of the reporting was evaluated based on a quality assessment form inspired by Nyambe et al. [21] (Table 2. The assessment was based on the following indicators: clarity of research questions/hypothesis/study aim; clarity of data collection methods; clarity of sampling plan; clarity of sampling size; clarity of analysis method; clarity of conclusions; clarity of limitations; citations; and ability to cross-reference. Each quality indicator allowed for a score from 0 to 2, except ability to cross-reference, which allowed a score from 0 to 1.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Characteristics of Literature Reviewed

4.2. Types of Challenges

| Category of Stakeholders | Challenges | Authors | No. of Mentions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recipients of finance | A. Product characteristics | [9,15,23,24,27,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43] | 20 |

| B. Livelihood assets | [9,15,23,27,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,44,45] | 18 | |

| Finance providers | C. Knowledge of agriculture and forestry sectors and of landscape finance | [9,27,33,36,42,43] | 6 |

| D. Scale, costs of services | [9,15,23,24,26,29,30,31,32,34,36,41,46] | 13 | |

| E. Transparency, trust, governance | [9,15,24,26,27,28,29,30,32,33,34,35,37,38,40,43,45,47] | 18 | |

| Cross-cutting—both finance recipients and providers | F. Production, climate, price, and policy risks | [9,24,27,29,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,42,43,46,47] | 15 |

| G. Lack of information, communication, roads | [9,23,27,29,30,31,32,34,39,41,42,44,45] | 14 | |

| H. Other benefits, policies, and regulations | [9,15,23,24,26,27,28,29,30,31,35,37,40,45,46,47] | 16 |

4.2.1. Main Challenges for Recipients

4.2.2. Main Challenges for the Finance Providers

4.2.3. Cross-Cutting Challenges

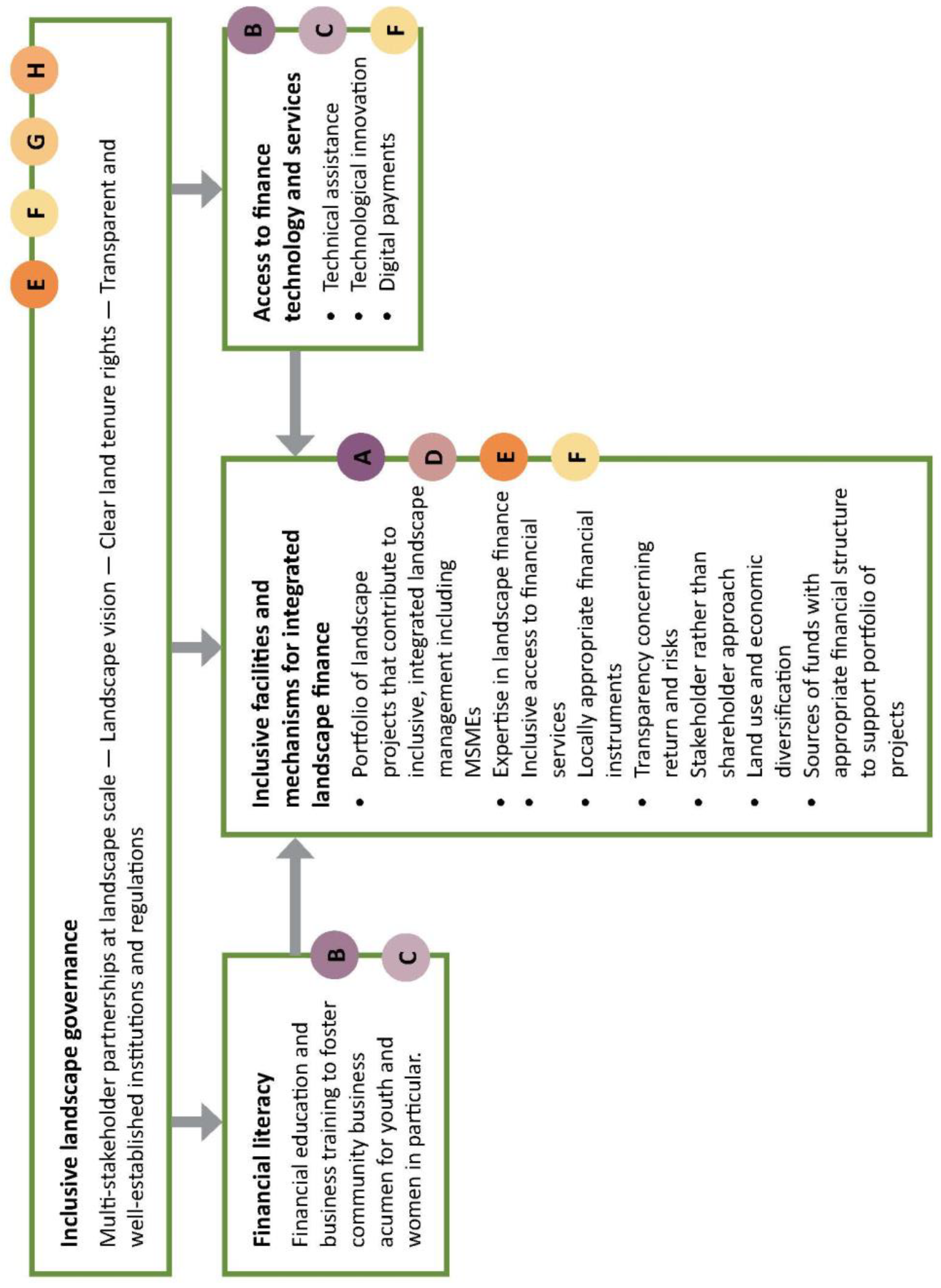

4.3. Overcoming the Challenges in Accessing Integrated Landscape Finance

4.3.1. Inclusive Landscape Governance and Local Stakeholder Collaboration

4.3.2. Strengthening the Financial Literacy of MSMEs

4.3.3. Access to Finance Technology and Services

4.3.4. Facilities and Mechanisms for Inclusive Integrated Landscape Finance

5. Towards Inclusive Finance for Integrated Landscape Management

5.1. Institutional Development for Inclusive Landscape Finance

- CSOs that build capacities in financial literacy, business acumen, and technical issues related to production and market access;

- Local financial institutions that develop locally appropriate financial instruments;

- Fund managers who translate the needs of the MSMEs into investible projects and design financial instruments through which public and private investors can invest in them;

- Landscape finance support service providers who can help connect MSMEs with FPs, coordinate and aggregate projects for synergies to meet landscape objectives, and incubate inclusive green businesses;

- In some cases, knowledge platforms through which fund managers can access investors and work with organizations that can provide the technical knowledge needed by local CSOs.

5.2. Enhancing the Landscape Finance Framework to Explicitly Address Inclusion

5.3. Implementing the Framework

6. Conclusions

6.1. Challenges and Innovations in Addressing Them

6.2. Lessons Learned

- How should facilities for inclusive integrated landscape finance be structured, and what are successful strategies to make them relate to local inclusive governance mechanisms?

- What actors need to be involved to be able to implement inclusive integrated landscape finance, and how should they relate to each other?

- Who should pay for improvements in the enabling conditions that facilitate the involvement of local actors (e.g., strengthening capacities, building trust)? Will such payments ensure future integrated investments or do they favor only those involved in a particular agrocommodity value chain?

- How can inclusiveness, as well as scale, impact, and diversity of investments, be achieved in landscapes with different sizes and mixes of stakeholders?

- What combinations of financial products best align with local circumstances to achieve various types of non-financial benefits, including health, education, and ecosystem services?

- Do inclusive integrated finance facilities lead to more sustainable landscapes (e.g., low or negative greenhouse gas emissions, maintenance or enhancement of biodiversity and of locally essential ecosystem services, contributions to income and well-being)? How do we measure this in a transparent way that is understandable to all actors?

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- 1000 Landscapes for 1 Billion People. Landscape Finance Framework; EcoAgriculture Partners, on behalf of 1000 Landscapes for 1 Billion People: Washington, DC, USA, 2022; in press. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change). Climate Change 2014 Mitigation of Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014; ISBN 978-11-0-741541-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO; UNEP. The State of the World’s Forests. Forests, Biodiversity and People; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020; ISBN 978-92-5-132419-6. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, B.M.; Hansen, J.; Rioux, J.; Stirling, C.M.; Twomlow, S.; Wollenberg, E.L. Urgent Action to Combat Climate Change and Its Impacts (SDG 13): Transforming Agriculture and Food Systems. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2018, 34, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, R.; Reed, J.; Sunderland, T. Bridging Funding Gaps for Climate and Sustainable Development: Pitfalls, Progress and Potential of Private Finance. Land Use Policy 2018, 71, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutz, A.; Heal, G.M.; Niu, R.; Swanson, E.; Townshend, T.; Zhu, L.; Delmar, A.; Meghji, A.; Sethi, S.A.; Tobin-de la Puente, J. Financing Nature: Closing the Global Biodiversity Financing Gap; The Paulson Institute: Chicago, IL, USA; The Nature Conservancy: Arlington, VA, USA; The Cornell Atkinson Center for Sustainability: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chiriac, D.; Naran, B. Examining the Climate Finance Gap for Small-Scale Agriculture; Climate Policy Initiative: Washington, DC, USA; IFAD: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Garnett, S.T.; Burgess, N.D.; Fa, J.E.; Fernández-Llamazares, Á.; Molnár, Z.; Robinson, C.J.; Watson, J.E.M.; Zander, K.K.; Austin, B.; Brondizio, E.S.; et al. A Spatial Overview of the Global Importance of Indigenous Lands for Conservation. Nat. Sustain. 2018, 1, 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louman, B.; Meybeck, A.; Mulder, G.; Brady, M.; Fremy, L.; Savenije, H.; Gitz, V.; Trines, E. Innovative Finance for Sustainable Landscapes; FTA Working Paper 7; The CGIAR Research Program on Forests, Trees and Agroforestry (FTA): Bogor, Indonesia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Shankar, S. Bridging the “Missing Middle” between Microfinance and SME Finance in South Asia. In SMEs in Developing Asia New Approaches to Overcoming Market Failures; Vandenberg, P., Chantapacdepong, P., Yoshino, N., Eds.; Asian Development Bank Institute: Tokyo, Japan, 2016; pp. 242–269. ISBN 978-4-89974-068-1. [Google Scholar]

- Louman, B.; Keenan, R.; Kleinschmit, D.; Atmadja, S.; Sitoe, A.; Nhantumbo, I.; de Camino, R.; Morales, J. SDG 13: Climate Action—Impacts on Forests and People. In Sustainable Development Goals: Their Impacts on Forests and People; Katila, P., Pierce Colfer, C., De Jong, W., Galloway, G., Pacheco, P., Winkel, G., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019; pp. 419–444. ISBN 978-1-10876-501-5. [Google Scholar]

- Soanes, M.; Shakya, C.; Walnycki, A.; Greene, S. Money Where It Matters: Designing Funds for the Frontier; IIED Issue Paper; IIED: London, UK, 2019; ISBN 978-1-78431-667-9. [Google Scholar]

- Guarnaschelli, S.; Limketkai, B.; Vandeputte, P. Financing Sustainable Land Use. Unlocking Business Opportunities in Sustainable Land Use with Blended Finance; Kois Invest: Elsene, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- IDH (The Sustainable Trade Initiative). Landscape Approaches: Raising the Bar through Landscape Approaches for Sustainable Production, Environmental Protection and Social Inclusion; IDH: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Shames, S.; Scherr, S. Mobilizing Finance across Sectors and Projects to Achieve Sustainable Landscapes: Emerging Models; EcoAgriculture Partners: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- IFC (International Finance Corporation). IFC Definition of Targeted Sectors. Available online: https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/industry_ext_content/ifc_external_corporate_site/financial+institutions/priorities/ifcs+definitions+of+targeted+sectors (accessed on 4 July 2022).

- Whittemore, R.; Knafl, K. The Integrative Review: Updated Methodology. J. Adv. Nurs. 2005, 52, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torraco, R.J. Writing Integrative Literature Reviews: Guidelines and Examples. Human. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2005, 4, 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, H. Literature Review as a Research Methodology—An Overview and Guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 104, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toronto, C.E.; Remington, R. A Step-by-Step Guide to Conducting an Integrative Review; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; ISBN 978-3-030-37504-1. [Google Scholar]

- Nyambe, A.; van Hal, G.; Kampen, J.K. Screening and Vaccination as Determined by the Social Ecological Model and the Theory of Triadic Influence: A Systematic Review. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamsheer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ Clin. Res. 2021, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boitano, G.; Abanto, D. Challenges of Financial Inclusion Policies in Peru. Rev. Finanz. Politica Econ. 2020, 12, 89–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shames, S.; Clarvis, M.H.; Kissinger, G. Financing Strategies for Integrated Landscape Investment: Synthesis Report; EcoAgriculture Partners: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, L. Financial Access of Latin America and Caribbean Firms: What Are the Roles of Institutional, Financial, and Economic Development? J. Emerg. Mark. Financ. 2021, 20, 227–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commonland; Conservation International; EcoAgriculture Partners; Landscape Finance Lab; Rainforest Alliance; Tech Matters; UN Development Programme. 1000 Landscapes for 1 Billion People. Strategy for Scaling Sustainable Landscape Solutions for People and Planet; EcoAgriculture Partners: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sleurink, A. Financing Integrated Water and Landscape Management in Africa: Barriers and Practices. Master’s Thesis, Erasmus University, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Setyowati, A.B. Governing Sustainable Finance: Insights from Indonesia. Clim. Policy 2020, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macqueen, D.; Benni, N.; Boscolo, M.; Zapata, J. Access to Finance for Forest and Farm Producer Organisations (FFPOs); FAO and IIED: London, UK, 2018; ISBN 978-92-5-131132-5. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, K.; Neufeldt, H. Biocarbon Projects in Agroforestry: Lessons from the Past for Future Development. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2014, 6, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayed, M.N.; Shusha, A. Determinants of Financial Inclusion in Egypt. Asian Econ. Financ. Rev. 2019, 9, 1383–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Joshi, P.; Cheng, E.; Birthal, P. Innovations in Financing of Agri-Food Value Chains in China and India: Lessons and Policies for Inclusive Financing. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2015, 7, 616–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarvis, M.; Bohensky, E.; Yarime, M. Can Resilience Thinking Inform Resilience Investments? Learning from Resilience Principles for Disaster Risk Reduction. Sustainability 2015, 7, 9048–9066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, A.; Gupta, A.K.; Singh, G. Innovation, Investment and Enterprise: Climate Resilient Entrepreneurial Pathways for Overcoming Poverty. Agric. Syst. 2019, 172, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnieux, G. Access to Finance for Cocoa Farmers; Access to Finance Working Group, Swiss Platform for Sustainable Cocoa: Bern, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Havemann, T.; Negra, C.; Werneck, F. Blended Finance for Agriculture: Exploring the Constraints and Possibilities of Combining Financial Instruments for Sustainable Transitions. Agric. Hum. Values 2020, 37, 1281–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middelberg, S.L. Value Chain Financing: Evidence from Zambia on Smallholder Access to Finance for Mechanization. Enterp. Dev. Microfinance 2017, 28, 112–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oostendorp, R.; Van Asseldonk, M.; Gathiaka, J.; Mulwa, R.; Radeny, M.; Recha, J.; Wattel, C.; van Wesenbeeck, L. Inclusive Agribusiness under Climate Change: A Brief Review of the Role of Finance. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2019, 41, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zougmore, R.B.; Läderach, P.; Campbell, B.M. Transforming Food Systems in Africa under Climate Change Pressure: Role of Climate-Smart Agriculture. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shames, S.; Scherr, S. Scaling Up Investment & Finance for Integrated Landscape Management: Challenges & Innovations; Finance Working Group of the Landscapes for People, Food and Nature Initiative: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Chima, M.; Babajide, A.; Adegboye, A.; Kehinde, S.; Fasheyitan, O. The Relevance of Financial Inclusion on Sustainable Economic Growth in Sub-Saharan African Nations. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchin, J.W. Environmental Conservation and the Risk Industry: A Natural Alignment of Interests. Geneva Pap. Risk Insur. Issues Pract. 2002, 27, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyers, D.; Bohorquez, J.; Cumming, T.; Emerton, L.; van den Heuvel, O.; Riva, M.; Victurine, R. Conservation Finance: A Framework; Conservation Finance Alliance: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, M.; Le, T.; Hoque, A. How Does Financial Literacy Impact on Inclusive Finance? Financ. Innov. 2021, 7, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenstock, T.S.; Lubberink, R.; Gondwe, S.; Manyise, T.; Dentoni, D. Inclusive and Adaptive Business Models for Climate-Smart Value Creation. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2020, 42, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenmaker, D. From Risk to Opportunity: A Framework for Sustainable Finance; RSM Series on Positive Change; Rotterdam School of Management, Erasmus University: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Govaerts, B.; Negra, C.; Camacho Villa, T.C.; Chavez Suarez, X.; Espinosa, A.D.; Fonteyne, S.; Gardeazabal, A.; Gonzalez, G.; Gopal Singh, R.; Kommerell, V.; et al. One CGIAR and the Integrated Agri-Food Systems Initiative: From Short-Termism to Transformation of the World’s Food Systems. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0252832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scoones, I. Sustainable Rural Livelihoods: A Framework for Analysis; IDS Working Paper 72; Institute of Development Studies: Brighton, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, M.; Mishra, R.; Mishra, K. Correlates of Financial Literacy: Strategic Precursor to Financial Inclusion. SCMS J. Indian Manag. 2019, 16, 16–30. Available online: https://www.scms.edu.in/uploads/journal/October-December-2019.pdf (accessed on 28 November 2021).

- Ullah, K.; Mohsin, A.Q.; Saboor, A.; Baig, S. Financial Inclusion, Socioeconomic Disaster Risks and Sustainable Mountain Development: Empirical Evidence from the Karakoram Valleys of Pakistan. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byakagaba, P.; Nantango, P.; Kalibwani, F. Finance for Integrated Landscape Management. De-Risking Smallholder Farmer Investments in Integrated Landscape Management: ECOTRUST’s Trees for Global Benefit (TGB) in Uganda; Environmental Conservation Trust of Uganda: Kampala, Uganda; Tropenbos International: Ede, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Louman, B. Financial Products Should Be Adjusted to Better Meet Needs of Community Forest Enterprises, Interview Series, Tropenbos News. 2019. Available online: https://www.tropenbos.org/news/financial+products+should+be+adjusted+to+better+meet+needs+of+community+forest+enterprises (accessed on 4 July 2022).

- Duong, T.T.; Brewer, T.; Luck, J.; Zander, K. A Global Review of Farmers’ Perceptions of Agricultural Risks and Risk Management Strategies. Agriculture 2019, 9, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, M.R.; De Janvry, A.; Sadoulet, E.; Sarris, A. Index-Based Weather Insurance for Developing Countries: A Review of Evidence and a Set of Propositions for up-Scaling; Working Paper 111; Fondation pour les études et Recherches sur le Développement International (Ferdi): Clermont-Ferrand, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hardaker, B.; Lien, G.; Anderson, J.; Huirne, R. Coping with Risk in Agriculture. Applied Decision Analysis, 3rd ed.; CABI Publishing: Wallingford, UK, 2015; ISBN 978-17-8-064574-2. [Google Scholar]

- OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). Managing Risk in Agriculture: A Holistic Approach; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mawesti, D.; Aryanto, T.; Yogi, Y.; Louman, B. Finance for Integrated Landscape Management: The Potential of Credit Unions in Indonesia to Catalyze Local Rural Development. The Case of Semandang Jaya Credit Union; Tropenbos International: Ede, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Worldbank; CIAT; CATIE. Agricultura Climáticamente Inteligente En Costa Rica; Serie de perfiles nacionales de agricultura climáticamente inteligente para América Latina; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2015.

- Kopparthi, M.S.; Kagabo, N. Is Value Chain Financing a Solution to the Problems and Challenges of Access to Finance of Small-scale Farmers in Rwanda? Manag. Financ. 2012, 38, 993–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumming, T.; Seidl, A.; Emerton, L.; Spenseley, A.; Kroner, R.; Uwineza, Y.; van Zyl, H. Building Sustainable Finance for Resilient Protected and Conserved Areas: Lessons from COVID-19. Parks 2021, 27, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villares, L. Blockchain and Conservation: Why Does It Matter. In Proceedings of the IDEAS 2019: Interdisciplinary Conference on Innovation, Desgin, Entrepreneurship, and Sustainable Systems, Manaus, Brazil, 17–19 July 2019; Smart Innovation, Systems and Technology. Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 198, pp. 346–355, ISBN 978-30-3-055373-9. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons, L.V.; Cloutier, S.A.; Coseo, P.J.; Barakat, A. Regenerative Development as an Integrative Paradigm and Methodology for Landscape Sustainability. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada-Carmona, N.; Hart, A.K.; DeClerck, F.A.; Harvey, C.A.; Milder, J.C. Integrated Landscape Management for Agriculture, Rural Livelihoods, and Ecosystem Conservation: An Assessment of Experience from Latin America and the Caribbean. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 129, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherr, S.J.; Shames, S.; Friedman, R. From Climate-Smart Agriculture to Climate Smart Landscapes. Agric. Food Sec. 2012, 1, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossanda, D.; Pamerneckyte, G.; Koesoetjahjo, I.; Louman, B. Report on Implementation of the Landscape Assessment of Financial Flows (LAFF) in Gunung Tarak Landscape, Indonesia; Tropenbos International: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hagazi, N.; Kassa, H.; Livingstone, J.; Haile, M.; Teshome, M. Financing Landscape Restoration in Ethiopia: A Case Study on the Bale Mountains Eco-Region REDD+ Carbon Finance Project; Technical Report; Penha: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, J.; Ickowitz, A.; Chervier, C.; Djoudi, H.; Moombe, K.; Ros-Tonen, M.; Yanou, M.; Yuliani, L.; Sunderland, T. Integrated Landscape Approaches in the Tropics: A Brief Stock-Take. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 104822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, D.; Louman, B. Finance for Integrated Landscape Management: A Landscape Approach to Climate-Smart Cocoa in the JuabesoBia Landscape, Ghana; Tropenbos International: Ede, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Degryse, H.; Ioannidou, V.; Liberti, J.M.; Sturgess, J. How Do Laws and Institutions Affect Recovery Rates for Collateral? Rev. Corp. Finance Stud. 2020, 9, 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, I.; Martinez Peria, M.S.; Singh, S. Collateral Registries for Movable Assets: Does Their Introduction Spur Firms’ Access to Bank Finance? Policy Research Working Paper 6477; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Starfinger, M. Financing Smallholder Tree Planting: Tree Collateral & Thai ‘Tree Banks’-Collateral 2.0? Land Use Policy 2021, 111, 105765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusters, K.; De Graaf, M.; Buck, L.; Galido, K.; Maindo, A.; Mendoza, H.; Nghi, T.H.; Purwanto, E.; Zagt, R. Inclusive Landscape Governance for Sustainable Development: Assessment Methodology and Lessons for Civil Society Organizations. Land 2020, 9, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siekei, J.; Wagoki, J.; Kalio, A. An Assessment of the Role of Financial Literacy on Performance of Small and Micro Enterprises: Case of Equity Group Foundation Training Program on SMEs in Njoro District, Kenya. Bus. Appl. Sci. 2013, 1, 250–271. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, J.; Kulathunga, K. How Does Financial Literacy Promote Sustainability in SMEs? A Developing Country Perspective. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korutaro Nkundabanyanga, S.; Kasozi, D.; Nalukenge, I.; Tauringana, V. Lending Terms, Financial Literacy and Formal Credit Accessibility. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2014, 41, 342–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaumba, A.A.; Wiafe, E.A.; Chawinga, S. Performance of Micro and Small Enterprises in Malawi: Do Village Savings and Loans Associations Matter? Small Enterp. Res. 2021, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ksoll, C.; Lilleør, H.B.; Lønborg, J.H.; Rasmussen, O.D. Impact of Village Savings and Loan Associations: Evidence from a Cluster Randomized Trial. J. Dev. Econ. 2016, 120, 70–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- imelton, E.; Mulia, R.; Nguyen, T.T.; Duong, T.M.; Le, H.X.; Tran, L.H.; Halbherr, L. Women’s Involvement in Coffee Agroforestry Value-Chains: Financial Training, Village Savings and Loans Associations, and Decision Power in Northwest Vietnam; CCAFS Working Paper 340; CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS): Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Proscovia, N.R.; Mugisha, J.; Bangizi, R.; Namwanje, D.; Kalyebara, R. Influence of Informal Financial Literacy Training on Financial Knowledge and Behavior of Rural Farmers: Evidence from Uganda. J. Dev. Agric. Econ. 2021, 13, 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development). OECD/INFE Core Competencies Framework on Financial Literacy for MSMEs; OECD: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Financial Access. Enhancing Financial Literacy: A Strategic Framework for Improving the Financial Literacy of MSMEs in Forest and Agricultura Value Chains; Tropenbos International: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas Rodriguez, E.; Saba Frick, N.; Ortiz Salvatierra, E.; Suarez Hoyos, L. Financiamiento Para La Gestión Integrada Del Paisaje. Fondo Rotatorio de La Asociación Forestal Indígena “Ascensión” Santa Cruz, Bolivia; Estudio de Caso: Santa Cruz de La Sierra, Bolivia; Fundación PROFIN: La Paz, Bolivia; Tropenbos International: Ede, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chien, J. Financing Gender Empowering Green Growth in Indonesia; Case Studies on Innovative Financing Mechanisms; IIX (Impact Investment Exchange): Singapore, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Demirgüç-Kunt, A.; Klapper, L.; Singer, D.; Ansar, S.; Hess, J. The Global Findex Database 2017: Measuring Financial Inclusion and the Fintech Revolution. Overview; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, W.; Huang, X.; Fang, H.; Wang, V.; Hua, Y.; Wang, J.; Haining, Y.; Dewei, Y.; Laihung, Y. Blockchain Technology in Current Agricultural Systems: From Techniques to Applications. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 143920–143937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indradjaja, B. Deloitte Indonesia Business and Industry Update. The Accelerating Digital Payments Landscape in Indonesia; Deloitte Touche Solutions: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Nan, W.; Zhu, X.; Lynne Markus, M. What We Know and Don’t Know about the Socioeconomic Impacts of Mobile Money in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Systematic Literature Review. Electron. J. Inf. Syst. Dev. Ctries 2021, 87, e12155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokossi, T. Mobile Money and Economic Activity: Evidence from Kenya. Unpublished Paper. 2017. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/31016100/Mobile_Money_and_Economic_Activity_Evidence_from_Kenya (accessed on 20 January 2022).

- Tropical Landscape Finance Facility. South East Asia’s First Sustainability Project Bond. 2021. Available online: https://www.tlffindonesia.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/RLU-Factsheet.pdf (accessed on 18 January 2022).

- Abraham, B.M. Ideology and Non-state Climate Action: Partnering and Design of REDD+ Projects. Int. Environ. Agreem. 2021, 21, 669–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dompreh, E.B.; Asare, R.; Gasparatos, A. Stakeholder Perceptions about the Drivers, Impacts and Barriers of Certification in the Ghanaian Cocoa and Oil Palm Sectors. Sustain. Sci. 2021, 16, 2101–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.; Samuelson, M.; Libanda, B.M.; Roe, D.; Alhassan, L. Getting Blended Finance to Where It’s Needed: The Case of CBNRM Enterprises in Southern Africa. Land 2022, 11, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otek Ntsama, U.Y.; Yan, C.; Nasiri, A.; Mbouombouo Mboungam, A.H. Green Bonds Issuance: Insights in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Int. J. Corporate Soc. Responsib. 2021, 6, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumarwan, A.; Kusuma, S.E. Why Do Individuals Choose to Become Credit Union Members? An Exploratory Study of Five Credit Unions in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Management & Entrepreneurship (2nd i-CoME), Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 26–28 July 2018; Petra Christian University: Surabaya, Indonesia, 2018; pp. 76–89. [Google Scholar]

| Framework Components | Guiding Questions |

|---|---|

| Inclusive landscape governance |

|

| Financial literacy of MSMEs |

|

| Access to finance technologies and services |

|

| Facilities and mechanisms for inclusive integrated landscape finance |

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Louman, B.; Girolami, E.D.; Shames, S.; Primo, L.G.; Gitz, V.; Scherr, S.J.; Meybeck, A.; Brady, M. Access to Landscape Finance for Small-Scale Producers and Local Communities: A Literature Review. Land 2022, 11, 1444. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11091444

Louman B, Girolami ED, Shames S, Primo LG, Gitz V, Scherr SJ, Meybeck A, Brady M. Access to Landscape Finance for Small-Scale Producers and Local Communities: A Literature Review. Land. 2022; 11(9):1444. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11091444

Chicago/Turabian StyleLouman, Bas, Erica Di Girolami, Seth Shames, Luis Gomes Primo, Vincent Gitz, Sara J. Scherr, Alexandre Meybeck, and Michael Brady. 2022. "Access to Landscape Finance for Small-Scale Producers and Local Communities: A Literature Review" Land 11, no. 9: 1444. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11091444

APA StyleLouman, B., Girolami, E. D., Shames, S., Primo, L. G., Gitz, V., Scherr, S. J., Meybeck, A., & Brady, M. (2022). Access to Landscape Finance for Small-Scale Producers and Local Communities: A Literature Review. Land, 11(9), 1444. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11091444