1. Introduction

The creation, protection and transmission of values and meanings (either in a tangible or intangible form) is one of the basic characteristics of every individual and society. It is a manifestation of culture and identity, defining ourselves in relation to the outside world and creating references to our existence. It defines and determines what is meaningful to us, reflects behavior and actions in space and time, successes and failures or situations, objects or elements and personalities that we do not want to forget for some specific reason. No facts stated are permanent; on the contrary, they are constantly evolving as humans and society develop. During life cycles, there is a constant re-evaluation of what we consider important or significant and what we do not. Whether due to changes in one’s own systems of values or attitudes; changes in the political, economic or cultural environment; natural events; and the influence of the environment, the creation of heritage takes place. This heritage is part of everyday space, as well as any landscape.

Heritage can be seen as a kind of mirror of a place and a time that presents to individuals and society what someone has chosen to protect and what they consider important. Of course, this mirror is not, and cannot always, be objective and universal for all. Therein lies its essence. We create heritage in such a way that it depicts what we want to see in it. It reflects the current state of society and it can also point out mistakes or injustices that are happening or have happened in the past. It then depends again on the state and values of the given society how are the reflected topics approached and whether the society learns from them or ignores them and risks their repetition.

The study of heritage is a very complex matter, it combines the approaches of many scientific disciplines and fields and it requires a very detailed insight into the issue as well as a critical approach to be understood and evaluated. Heritage research combines different methods to facilitate a holistic view. It is necessary to combine approaches and concepts relating to and exploring the tangible and intangible components of heritage, their temporal and spatial context, natural and social aspects, but at the same time not to forget about mutual cultural, economic, or social ties and relationships. The synthesis of these spheres then leads to a comprehensive understanding of the studied heritage, which can contribute to its understanding or development, and, at the same time, to its semantic differentiation on various geographical scales. Heritage is, in a way, a reflection of the values in the settings of companies and individuals in different regions of the world. In the complex of our natural and cultural heritage, we can identify our approach towards nature conservation, natural resource management, historical events, war conflicts and important personalities. At the same time, it reflects the social, cultural and political, but also economic, development of society, ways of farming in the landscape and social relations.

2. Heritage Research

The concept of heritage has been discussed internationally for quite a long time and it is considered one of the key concepts of cultural or historical geography [

1,

2]. Heritage research is interdisciplinary in nature, and a combination of approaches from multiple scientific disciplines and fields is necessary to understand its meaning and essence. At the beginning of the 1990s, a new multidisciplinary field called

heritage studies was formed. The field is dedicated to heritage research and combines approaches and methods, such as archaeology, historiography, social and cultural anthropology, historical and cultural geography, or ethnography [

1,

3]. Heritage research focuses not only on heritage types, forms, but above all on values or meanings, their representation and interpretation by individual stakeholders, influences on the formation of identities and conflicts arising from different perceptions of heritage [

1,

4]. One of the disciplines dealing with the study of heritage is geography, which can investigate the differentiation of heritage in space and the consequences of its presence in the territory on local and regional development, tourism, economy or influences on the inhabitants living in heritage areas [

5].

In cultural geography, interests in heritage issues develop roughly at the same time as in historical geography. In the 1980s, in the context of the birth of the postmodern (post-material) society, the so-called new cultural geography was formed. It focuses more on the issue of culture in broad social contexts [

6]. It is the study of the use of certain elements and the values and meanings that are given to them in time, which is the essence of heritage [

7]. It also studies the benefits of heritage occurrence in the territory on local or regional development, tourism, or influences on the social and political functioning of society [

1]. However, the conceptualization of heritage as a meaning (whether cultural or ideological) and process, rather than as an artifact, inevitably leads to conflicts and tensions caused by different ways of perceiving (the same) heritage by different stakeholders, entities, or interest groups [

4,

8].

In the context of the geographical approach to the study of heritage, it is important to mention some of the other geographical concepts that are closely related to heritage. Since heritage helps to create the meanings of places, its values and meanings are reflected in the perception of these places by inhabitants—both local and from other places. Geographical spaces (landscapes) differ from each other due to many attributes [

9], which also include heritage. Another of these attributes, in addition to the heritage, is also the meaning of the place. It is, therefore, important to mention the concept and concept of “place”, which is studied primarily in human geography [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. The place is understood as part of a large and undifferentiated geographical space. Tuan [

15] p. 6 argues that “

space is more abstract than place”. In cultural geography, heritage is often associated with the perception of a place (a specific space where the heritage is located), which is also associated with its subsequent interpretation, especially in the formation of spatial identity [

19]. According to Tuan [

16], space becomes a place when it is given a meaning that distinguishes it from others, and it is possible to identify with such a place. Certain places have stronger meanings for individuals or groups (communities) than other places (sense of place). An example might be that an interesting event, a major battle, or natural disaster took place in a place in the past, or a significant economic activity took place there. The importance of the place is associated with the identity of both residents, members of the local community and visitors [

18]. Its meanings can also be strengthened by the institutional dimension, i.e., when it is protected at the national or international level (e.g., designation as a cultural or national cultural monument by the state heritage authorities of Czechia or inclusion on the UNESCO World Heritage List).

Heritage provides representations of values and meanings from the past that support the meanings of places or the sense of belonging of a particular community [

20,

21,

22], interpreting and presenting itself externally considering the given values [

23]. Heritage can be seen as one of the attributes that shape not only people’s personal values, opinions, or identities, but also influences the patterns of behavior and actions of persons or groups and it shapes the collective memory [

24]. Within the topics of the new cultural geography, not only the importance of heritage for the formation of territorial identities and the meanings of heritage for the formation of identities of a given (cultural) society are studied, but also their conflicts. Research into identities in relation to heritage is mainly conditioned by their mutual relationship [

25].

An important component of the heritage complex is also the landscape, which is part of our environment, it is part of the world that shapes us, and it has an impact on the quality of our life. It has many functions—in addition to the working environment or a source of livelihood, it is also a place of rest and regeneration. It is indispensable and its aesthetic value is often crucial as well. The landscape is, therefore, part of the cultural heritage, or it is possible to talk about the heritage of the landscape. What we perceive today as nature is mainly a cultural landscape transformed by human activity during the process of settlement and cultivation. The thousand-year development of the country has left several traces in the landscape. It has become an open chronicle of our history, culture and identity. That is why the 1972 UNESCO Convention for the Protection of the Cultural Heritage characterizes the cultural landscape as “a combined work of nature and man and evidence of the development of human society and settlements throughout history.” Selected parts of the cultural landscape are, therefore, protected by law or international conventions. An important means of gaining respect and esteem, which lead to protection and preservation for future generations, is to acquaint the public with the landscape as part of our cultural heritage and the legacy contained in it.

The European Landscape Convention is also an important document dealing with landscape protection. It covers all landscapes, both outstanding and ordinary, that determine the quality of people’s living environment. The text provides a flexible approach to the landscape, the specific features of which require different types of actions, from strict protection through protection, management and improvement to self-creation.

3. Mining Landscape as a Heritage

Heritage is formed in all fields of human activity, industrial production, and the activities associated with it are therefore no exception. Howard [

1] distinguishes seven categories of heritage (nature, landscape, monuments, places, artifacts, activities and people), Mazáč [

26] classifies heritage according to the fields of human activity (transport, spa, metallurgy, mining, glassmaking, etc.). Industry is an important sector of national and world economies, employs many people and conditions the economic development of regions. At the same time, it is developing and changing very dynamically, while it is closely linked to education and scientific and technical progress. Thus, within the framework of industrial activities and activities, a wide spectrum of both tangible and intangible heritage can arise, representing values and meanings related to various aspects of industrial production. This complex can be called an industrial heritage and creates industrial and mining landscapes.

As a result of social changes, industry and its individual elements (plants, premises) cease to fulfil their original functions on a large scale, and, therefore, discussions about their future use appear [

27]. The basic problem discussed is the identification and determination of industrial elements or landscapes that should be preserved, protected and, finally, used if they become industrial landscape heritage [

28].

Industrial heritage often arises secondarily, i.e., by transforming the original function of a given element. This is where the intersection takes place, where it is possible to state that brownfields can be the basic constituting elements in the creation of industrial heritage. However, the role of individual actors and entities in the brownfield management is important. In order to be described as transformed into heritage, the elements need to represent and interpret certain values and meanings associated with industry or its meanings (see above for the general definition of heritage).

In order to employ the industrial elements further in the fulfillment of the function of heritage, it is necessary to change their perception by the society as it is often affected by their current state, environmental burdens, or unresolved property disputes. If industrial history or its legacies and meanings are not to disappear, but, on the contrary, become an important part of cultural and social life, there are certain characteristics that industrial elements should meet to become attractive in terms of the future development or investment and to become industrial heritage [

29]. These are the characteristics that industrial elements should contain and combine:

enrichment of the environment—evidence of artistic ambition and technical innovation, authenticity of the place—genius loci;

destination—connecting people, dominant landmarks of the city and landscape, identification of inhabitants with projects, memory of the place, continuity of traditions;

sustainable development—recognition of values and differentiated approach, financial and technical adequacy, balancing of risks and benefits, method of gradual steps, interconnection of public interest and business structures, formulation of a vision.

For the industrial heritage to be preserved for future generations, it is necessary to set up effective systems for its protection (both at the national and international level), which will regulate and guarantee the preservation of its specific values and meanings, provide quality management strategies and, at the same time, outline visions for development into the future.

One of the categories of industrial heritage is, in relation to the origins of industry, mining and metallurgy. Mining heritage refers to the extraction of mineral resources and the associated accompanying processes (exploration, energy sources, horizontal or vertical transport, etc.) as well as the ways of life of mining communities. Mining is considered an important industry, but the material remnants of mining activities (especially from the period of massive industrialization) have long been referred to as unsightly landscape elements. In the past, efforts to erase traces of mining from the landscape and memory of the inhabitants prevailed rather than to preserve them and use them for new purposes as a heritage [

29]. However, the remains of mining activities often represent historical and cultural values associated with the technical maturity and skill of our ancestors, as well as the lives of mining communities, their traditions, customs, or religion [

30].

Mining is also interesting because without mining, almost no (not only) industrial production could be conducted and it is, therefore, a kind of starting link of the whole process of production and construction activities. In addition to the food production, mining and processing of mineral resources is one of the basic human activities that can be reliably detected in prehistoric times [

31]. Entire eras of human history are then named after the predominant raw material extracted and used (Bronze Age, Iron Age, etc.). In the past, mining was usually associated with the development of entire regions. Miners brought to the territory not only specific knowledge and skills, but also culture, traditions and religion. With the gradual development of science and technology, people got deeper and deeper underground, discovering new sources of raw materials and ways of their processing and use. At the same time, they improved mining techniques and increased the amount of material extracted. However, mining leaves extensive traces, it transforms the landscape and society, and after the end of mining activities, the question always arises of what to do with the complex of relics [

32,

33]. With the end of mining, there is also usually stagnation and transformation of the local and regional economy and social environment, and new economic activities are sought to compensate for the loss of income. At the same time, mining and accompanying operations employ a number of people who are at risk of unemployment after the mining processes have ended.

The history of mining is very varied and several hundreds (up to thousands) of years long. The time aspect is one of the important aspects of the management of landscape heritage and the given heritage complexes (in this case the mining heritage) must be viewed from a broad and detached perspective. There are many landscape complexes representing the mining heritage. Internationally, the UNESCO Heritage Listing can be considered the highest level of protection, with more than one hundred industrial heritage sites (e.g., the industrial landscape around Blaenavon in the United Kingdom or the copper mining area around Falun in Sweden) as of 2021.

Each mining area is characterized primarily by the mined raw material (or their combination), the time and spatial extent of mining or the mining technology used. However, it is possible to define certain common features and problems inherent in most mining areas. A fundamental and frequent phenomenon is the vastness of the area concerned, especially in surface mining. However, even in underground mining, large areas on the surface are taken over, for example, due to the deposition of the excavated material that is not subsequently processed (tailings). Environmental burdens, such as the presence of heavy metals in the soil or the contamination of groundwater by operating fluids [

32], can be a risk. After the closure of mining activities, it is necessary to treat the affected or contaminated areas in a certain way. As a rule, mine reclamation takes place in order to remediate polluted areas, obliterate anthropogenic interventions in the landscape and, thus, create a completely new type of landscape for a subsequent use. The aim of the reclamation is to restore the ecological and aesthetic functions as well as the economic and recreational potential of the area degraded or devastated by anthropogenic influences and to integrate the site into the context of the surrounding landscape. This is a very complex process, but the aim of which should not be to completely “erase” the image of mining from the landscape and to create the illusion that it has never taken place in the area. It is important to preserve and develop the essential elements referring to mining and miners, i.e., to shape the mining heritage. However, there are many remains left after mining, and it is not possible or appropriate to consider all of them as heritage. Professional selection of elements and identification of their specific cultural or other values and meanings that should be preserved, protected and interpreted is necessary. These tasks are based on actors, entities and interest groups involved in the process of heritage creation, i.e., public, private or non-profit institutions [

34]. The remains of mining activities are an integral part of the post-industrial or post- mining landscape, which deserves increased protection and attention, as it is evidence not only of the mining, but also of the cultural, social and environmental history of the regions [

35]. The mining heritage represents the shift of society from material to post-material values.

4. Mining Cultural Landscape of the Krušnohoří/Erzgebirge

In Czechia, one of the important examples of mining landscapes is the Mining Cultural Landscape of the Krušnohoří/Erzgebirge, which was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2019. This step is a fundamental shift in the perception of the values and meanings of the landscape’s mining heritage, both locally and mainly internationally, and it confirms the direction set after 1990, i.e., the selection and protection of selected mining elements as an important part of the cultural heritage of (not only) Czechia and of the efforts to preserve it for future generations.

The Ore Mountains are situated on the western border of the Czechia and Germany, where they form a continuous mountain range without significant crossings and passes with a length of almost 130 and a width of about 40 km. Thanks to the diverse geological development, the area has been very important since the 12th century. Mining landscapes can be found on both sides of the border, while the whole region is specific by their high concentration, extraordinary preservation, and diversity, but also by territorial vastness and long-standing mining traditions such as mining processions, celebrations, or mining bands [

36].

The efforts to recognize the unique values of the local mining heritage were evident earlier on the German side than on the Czech side of the mountains. At the end of the 1990s, initiatives of citizens and institutions seeking to inscribe the mining region’s mining heritage on the UNESCO list came to the fore. On the German side, the first steps towards the nomination were implemented already in 1998 and in 2003 the association Förderverein Montanregion Erzgebirge was established. After roughly ten years, Czechia got also involved, and in 2013, a joint Czech-German nomination was submitted to UNESCO. It was then approved in 2019. An overview of the parts of the mining cultural landscape of the Krušnohoří/Erzgebirge inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List can be found in

Table 1.

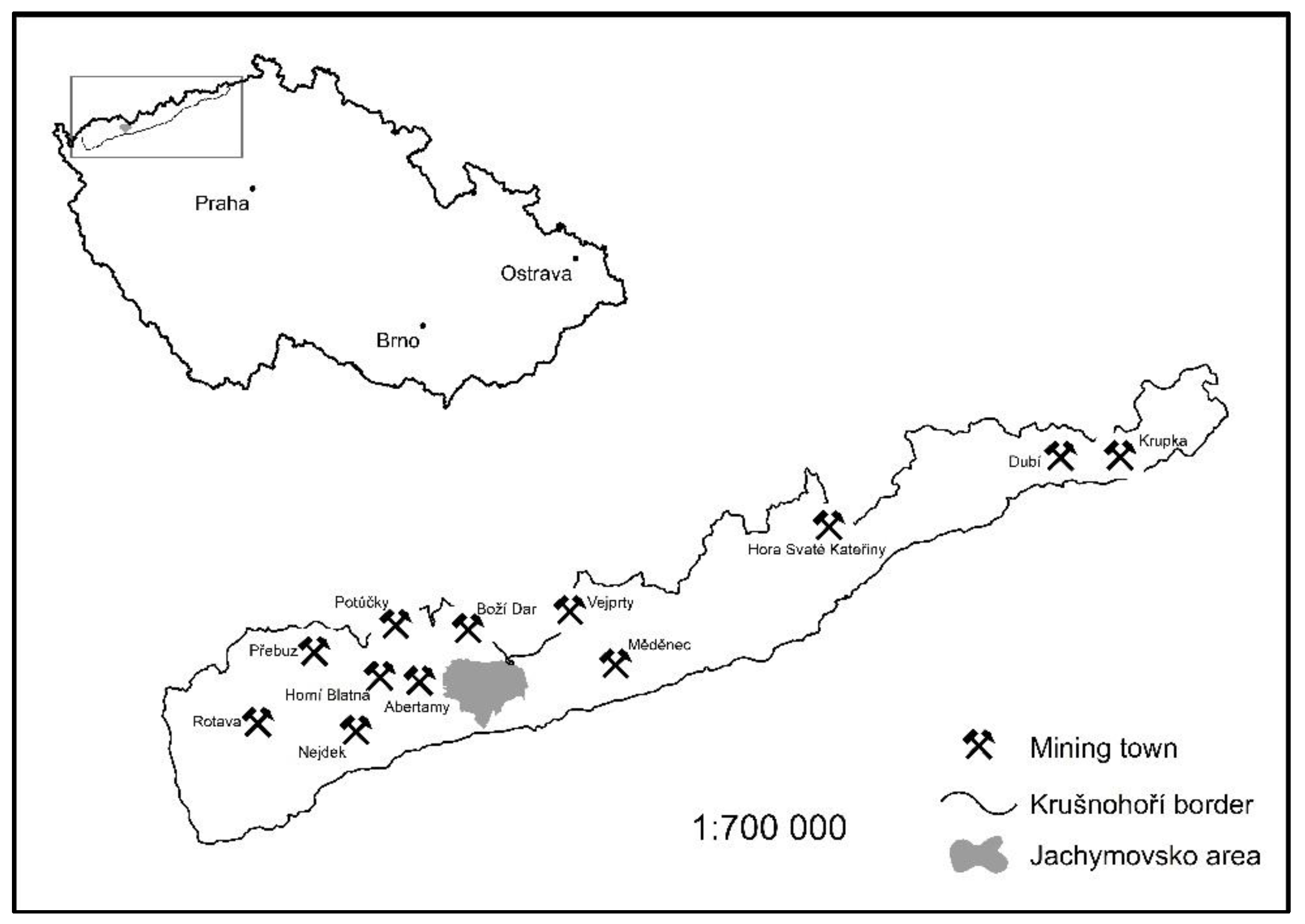

One of the components of the Czech part is the mining cultural landscape of Jáchymov, which is very diverse in the structure and approach of individual actors to the management of the mining heritage. At the same time, it is a key region of the nomination (due to the values and meanings that the local mining heritage represents) and there are very often clashes of visions of the actors, entities and interest groups, and of their expectations and assumptions about the development after the inscription of the heritage on the UNESCO World Heritage List. Not only for these reasons, the Jáchymov region was chosen as an area of interest for intensive research (location of the area of interest see in

Figure 1). As part of the doctoral research for the dissertation.

The mining heritage of the Jáchymov region as a dynamic sociocultural process [

36], this area was subject to long-term intensive research, which was focused on how the local mining heritage and mining landscapes are formed by the actors in the territory (private, public, and non-profit sectors).

5. Data and Methods

The main goal of the article is to analyze and evaluate the approaches groups of actors to the management of mining heritage in the presented area of the Jáchymov region. Three groups of actors have been identified: the public, the private and the non-profit sector. For each group, the initial hypotheses were determined in advance and subsequently verified. The hypotheses are based primarily on the general functioning and settings of individual groups of actors. The aim was, therefore, to verify whether the philosophies presented in the hypotheses are also held by the actors in the area of interest. Furthermore, it is possible to notice any changes over time [

4,

5,

21,

37]. The basic research question is that the presented hypotheses correspond to reality

The public sector will be greatly influenced by current political events. It is possible to assume the use of the values and meanings of the mining heritage to consolidate power or to promote the position and visibility of individual subjects;

The private sector will tend to commodify heritage and use it only for tourism or other gainful activities. Here it is possible to assume a lower interest in transmitting the values or meanings of the heritage;

The non-profit sector will overestimate the importance of the mining heritage. At the same time, there is a presumption of lower professional qualification of individual entities, or a more problematic approach to the funding of individual projects. On the contrary, this can be compensated by a personal approach and enthusiasm.

Qualitative research in the area of interest was carried out using semi-structured interviews and it took place at three levels. At the first level, interviews were conducted with actors involved in the formation, interpretation, use, management and protection of the mining heritage, with emphasis on the inclusion of actors from all sectors (public, private, non-profit). These actors include, for example, owners or managers of exhibitions and museums, representatives of selected institutions, members of local mining associations and others. The survey was focused on the attitudes towards the mining heritage, but also, for example, on the links or relationships between the individual actors. At the second level, interviews with residents were carried out. These interviews are used to gather information about the influence of the presence of the mining heritage on the formation of their subjective values, attitudes, and identities. The research focused on the analysis of the relationship of the inhabitants to the mining heritage in their surroundings. At the last level, interviews with visitors to the territory were carried out. Interviews of this type investigated visitors’ awareness of the local mining heritage or the perception of its presentation and interpretation by institutions. The combination of these three levels allows a comprehensive view of the studied issue from different perspectives and seeks interconnection of activities, relationships and links between their originators and target groups.

Interviews with all research participants took place in the form of personal meetings, which gave individual respondents the opportunity to assess their personal attitudes, while meetings with individual respondents took place in the area of interest. Each group of interviews was conducted according to a pre-prepared syllabus, respectively. Structures of questions, but as a rule, the interviews were of a more unformal nature, so that the respondents did not feel limited and could express themselves freely on the topic. For this reason, audio recording was not strictly required, i.e., if the respondents showed reluctance or shyness to record, only written notes were taken from the interview. The interviews were designed so that respondents had maximum space to express their views and attitudes, so the majority of questions were open.

Both research interviews parts (with residents and with representatives of institutions) had a similar structure both among the representatives of the institutions and among the local population. The representatives of the institutions first introduced their institutions, then they had to evaluate how they participate in the management of the montane heritage or for what purpose they manage it.

On the contrary, the local inhabitants had to express their attitudes and opinions on the specific institutions, they had to evaluate how they deal with the montane heritage and how they perceive it.

The duration of each interview was usually 30 to 60 min, all participants were acquainted with its purpose, anonymization of data and agreed to use the answers for the needs of the dissertation. The obtained textual materials (audio recordings were converted into written form) were subsequently evaluated by the text coding method, which collected specific information that was needed to meet the research objectives. In some cases (e.g., when asking about the perception of various facts), the respondents chose the answers on a given scale (completely positive × rather positive × rather negative × completely negative) [

38,

39,

40].

The field research took place in the Jáchymov region between 2017 and 2020. A total of 157 research interviews took place over four years, of which 95 were with residents and 62 with representatives of institutions. Overviews of the number of interviews with respondents can be found in

Table 2 and

Table 3. Given that it was an effort to address the same respondents and to record shifts in their perception and views on the Jáchymov mining heritage over time, it can be stated that the presented research covers a short but significant part of the process of the existence of the heritage and that it records probably the most important shift in the process of its protection, namely the inscription on the UNESCO World Heritage List.

6. Results

Prior to the research itself, three assumptions were established

- 1.

The public sector will be greatly influenced by current political events. It is possible to assume the use of the values and meanings of the mining heritage to consolidate power or to promote the position and visibility of individual subjects.

This assumption was only partially confirmed in the partial findings. The influence of the current political situation is particularly evident in the topic referring to uranium ore mining in the second half of the 20th century. The presentation and interpretation of this heritage is very complex, and the institutions pride themselves on a neutral approach and presentation of facts. It is quite possible to confirm that the mining heritage is used to raise the profile of individual subjects. Over time, there is a certain shift; especially after 2019 (after the inscription on the UNESCO list), the public sector is trying to present and use the mining heritage for the general public. The inscription of the Jáchymov mining heritage on the UNESCO World Heritage List was used by all local or regional politicians for their own PR. Institutions established by the public sector use the mining heritage to make themselves visible and attract visitors (some are directly established for this purpose—e.g., regional museums), but they are usually institutions at the local or regional level. Institutions at national level use mining heritage only if they have the task of managing and protecting values, while others use its values and meanings very rarely or not at all. At the same time, during the research period, elections to the Jáchymov municipal council took place (autumn 2018), but it was not found that some candidates or parties used the topic of mining heritage in election campaigns. At the same time, these elections did not bring any fundamental change in the town management (the mayor of town has been the same person since 2008).

- 2.

The private sector will tend to commodify heritage, use it only for tourism or other gainful activities. Here it is possible to assume a lower interest in transmitting the values or meanings of the heritage.

This assumption has been confirmed at almost completely at all the levels. At the local level, the private sector makes purposeful use of the mining heritage to present and promote its commercial activities, whether they are restaurants or accommodation facilities. The use of material heritage (various objects or artefacts) is used to increase the attractiveness of the place, but also the mining symbolism itself or the connection with the mining past in names, promotional materials, or equipment of the operations. An example at the regional level can be the Jáchymov spa, which uses the Svornost mine almost exclusively for commercial purposes (pumping radon-containing water for the needs of the spa). The representation and presentation of the mining heritage is up to the point. While there are efforts to present certain specific elements, the most valuable heritage remains out of focus. Similarly, private companies do not attach as much importance to the transmission of values. Even here, however, a slight shift is evident during the research years, since the inscription on the UNESCO list, most actors promise an influx of a larger number of tourists. This is associated with the expectation of higher profits. However, at the end of the research, a COVID-19 pandemic broke out, so actors also mentioned that they were afraid of future developments.

- 3.

The non-profit sector will overestimate the importance of the mining heritage. At the same time, there is a presumption of lower professional qualification of individual entities, or a more problematic approach to the funding of individual projects. On the contrary, this can be compensated by a personal approach and enthusiasm.

This assumption has also been confirmed, although its empirical verification is only partial. It was not possible to find out the professional qualifications or education of all representatives of the non-profit sector, so it is not possible to state with certainty that they have insufficient professional qualifications for dealing with heritage (some respondents refused to disclose their level of education). It is also possible to confirm that the non-profit sector does not draw subsidies to a greater extent, the funding is rather obtained via contributions from individual members. Finally, it is certainly possible to confirm that the non-profit sector attaches the highest importance to the mining heritage of all the sectors, it considers it to be a significant development potential of the town and at the same time it places great hopes in it for the future development. This is also related to the confirmation of the last part that members of the non-profit sector have a personal approach to the administration or management.

Research also shows that actors and residents are proud of the presence of the mining heritage in the area and that they would like to use it both to strengthen their internal identity and, above all, for the needs of the mining tourism, the strengthening of which is expected from the inscription of the site on the UNESCO World Heritage List. However, the analysis of the steps that should lead to the use of the UNESCO label shows that the approach of the actors is very “lukewarm” and there are recognizable tendencies relying on the brand itself rather than on the follow-up activities of other entities, as Hall [

41] warns. In the interviews, it is possible to observe an interesting clash of expectations of benefits, but, at the same time, the absence of specific steps. This can lead to negative consequences. As stated by VanBlarcom, Kayahan [

42], it is not possible to rely only on the UNESCO label itself, but it is necessary to initiate and implement partial steps taken by all the stakeholders. Here again, a very important element is manifested, which is mentioned by Yuksel F., Brambwell, Yuksel A. [

43], and that is communication and cooperation between individual actors and entities. However, it is clear from the research that the cooperation does not take place between all subjects or levels, the most noticeable is the absence of cooperation between the town of Jáchymov and the non-profit sector, there is also minimal cooperation between institutions at the regional level (museums) and the town or between the private sector represented by the spa and the public or diverse associations with specific interests. In the future, there may be a problem of a clash of expectations, where all actors state that they expect positive effects on employment in the region or on tourism, while the lack of catering and accommodation facilities is very often mentioned. However, the same is true of new exhibitions.

In conclusion, it is important to state that the research was focused only on a certain selected direction and that it provides a view of the Jáchymov mining heritage only from the point of view of the actors and residents. For a more comprehensive view or to obtain further information, it would be possible to carry out research, for example, among visitors to the town (tourists), and in terms of information about the Jáchymov mining heritage, other possibilities are offered, such as a survey in schools, which would be aimed at determining the knowledge and awareness of primary and secondary school pupils about the Jáchymov region and its mining heritage. It would be also possible to carry out an investigation in other parts of the Karlovy Vary Region or the Czechia, which could reveal awareness and perception of this type of heritage in other territories as well.

7. Discussion

The presented research provides a unique insight into the thinking and perception of individual actors in four time periods that are not distant from each other. It captures the opinions of respondents before the actual inscription of the Mining Cultural Landscape of the Krušnohoří/Erzgebirge on the UNESCO World Heritage List (2017–2018), just after its implementation (2019) and then one year later (2020). However, it is important to remember that the interviews do not involve all actors. The results of the research also need to be seen in a broader context, as they may be influenced by other factors, one of which is, for example, the global COVID-19 pandemic and the related emergency measures in 2020.

As to the selection of actors, it has already been stated that they were representatives from all sectors and levels, and the overall view shows a considerable fragmentation and inconsistency in dealing with the Jáchymov mining heritage. Individual actors manage different types of heritage through diverse institutions, but due to the rich mining history and the abundance of elements in the territory, there are also many different approaches. In terms of the ways of managing the public sector at the local level, there is no larger institution. Although the town of Jáchymov runs an information centre, the largest exhibitions (the Royal Mint Museum and the Gallery No. 1, Jáchymov, Czechia) are administered by regional institutions (Muzeum Karlovy Vary, Karlovy Vary, Czechia and Muzeum Sokolov, Sokolov, Czechia), i.e., from the regional level. This situation has its historical origins and there are no efforts or tendencies to change it. However, there can be a potential conflict where the town citizens may feel that the local government is not involved sufficiently in the management of the mining heritage. In general, the analysis of the mining heritage shows that individual actors manage, interpret, and present the administered heritage according to their position. This was confirmed by the first phase of the research, during which the attitudes and approaches of actors dealing with the mining heritage from different levels or sectors were examined.

From the point of view of the chosen methodology, it is important to evaluate its disadvantages, which may include, for example, the risk of the researcher interfering in the monitored situation, and, thus, the risk of skewing the results in data collection or evaluation and interpretation. Thus, personal attitudes, previous experience, researcher’s preferences and possible sympathy/antipathy towards respondents are inevitably reflected in the survey results [

44]. In the research, the effort was to reduce these negative aspects of the chosen method by verifying the findings from secondary sources or by conducting interviews with several representatives of one institution (in the case of visitors and locals were then implemented with a sufficient number of people to representative sample). Despite the above-mentioned disadvantages, the chosen methods outweigh its advantages, especially the possibility to look into the depth of the studied problem, which other methods do not allow.

8. Conclusions

In each landscape, it is possible to find products of human activities that are important to individuals or communities, contain specific values or meanings intended to be passed on to future generations [

1,

4]. These meanings can be assigned to elements at the time of their formation, but they can also be discovered only during their life cycle. In today’s dynamically changing society, rapid development takes place, and some elements lose their original purpose very shortly after their creation. Sometimes, so quickly that there is no realization that with their demise there may be the extinction of a part of history and significant values that may contain or have been given to them. Therefore, it is very important to constantly re-evaluate whether in certain phases of life cycles it is not time to re-vocalize their perception, or whether to try to discover these values and meanings and work with them—that is, whether to start the process of creating the landscape heritage [

8,

42,

43,

44]. Landscape developments can be created in almost all aspects of human activity, as well as the values and meanings of natural phenomena and elements.

If a certain human activity (industrial or agricultural activity, etc.) has been carried out in a region for a long time, there is usually an accumulation of remains that document, remind or are in some way connected with its existence. The more intensive this activity is, the more people it employs or transforms the landscape and the more are its remains engraved in people’s memories, creating specific environments and communities, and usually starting the process of creating heritage [

45]. It is no different in the case of mineral extraction areas, with one of the largest and most important regions in Czechia being the Ore Mountains [

46]. More than 800 years of mineral extraction have left a unique complex of remains on the Czech and German side of the mountains, which has been formed, processed, interpreted and protected as a mining heritage for several decades. Its significance is underlined, among other things, by its inscription on the UNESCO World Heritage List, which can be considered not only an important act in terms of its institutional protection, but a confirmation of the values and significance of local mining activities not only for Czechia, but also for the world.

The Jáchymov region is interesting not only for the diversity and number of elements of the mining heritage, but also for the existing approaches that also influence the heritage. In terms of historical development and represented values and meanings, the Jáchymov heritage is closely intertwined with and forms a complex of a world importance. However, it is no longer possible to talk about a comprehensive approach to this heritage from the point of view of the actors mentioned, whether it is approaches to its protection or interpretation or management. Jáchymov is also the scene of a clash of views and disputes of various actors involved or interest groups from various sectors that participate in the process of creating a mining heritage.

For the successful management of heritage (not only mining), the involvement and cooperation of all groups of actors operating across levels in the territory is crucial, and at the same time close cooperation with residents is very important. What is important is the realization that the heritage does not only serve the needs of one interest group, which can unilaterally use it; for example, the needs of tourism or economic purposes. Heritage should be created for a wide range of inhabitants and visitors, and it should primarily serve both for the representation and interpretation of values and meanings, as well as for residents, fulfilling and forming their territorial identities or building relationships and attitudes towards it. Without participation from the bottom up, i.e., the involvement of the local population, there may be a commodification of heritage and the loss of the values represented by it, which can be demonstrated in various specific cases. The environment administered and interpreted by local stakeholders is often perceived much more positively by the inhabitants of the region in which it occurs than that which is managed by private actors and institutions. Active and continuous cooperation between the various sectors and an open dialogue with representatives of local governments are important, and its absence can break the very delicate balance of relations in the territory between the use of heritage by visitors and residents. It is important that the locals feel a sense of belonging to the heritage, consider it their own (they are proud of it), which is a necessary step towards its quality interpretation (also towards visitors to the city).

Another generalizable finding resulting from the research is that heritage must be perceived as a complex, i.e., a coherent set of phenomena and elements. The historical development of the territory does not have to be continuous [

47], and all development phases are reflected in some way in the present. Without an understanding of the context, there may be misinterpretations or misunderstandings related to this. Therefore, it is not possible to exclude certain periods of time or specific activities from the creation and complex of heritage, although they may be perceived as contradictory and cause conflicts between actors. Even a negative or contradictory heritage can contain important values and meanings that need to be preserved and transmitted. The essence of the definition implies that any heritage can be perceived inconsistently [

21,

48] and it is important to take positions and to provide a quality interpretation.

The final observation is that the value and significance of the heritage are not necessarily related to and correspond to the ways of its interpretation and protection. Even a world-renowned locality or element may be overlooked in the landscape (figuratively speaking), or the values and meanings it represents may not be represented, as there is no rule or regulation that determines how the heritage is to be transmitted and presented. It is, therefore, possible to observe situations where the primary function of heritage is de facto suppressed by purposeful exploitation. Therefore, it can be concluded that it is very important to first thoroughly evaluate and define the values and meanings that a particular element can represent and transmit and interpret them accordingly. It is essential to discover these values and meanings in time and not to neglect them. In the case of use for purposes other than cultural tourism, it is necessary to look for compromises and intersections in the usually commercial use and representation of values (even though this may often seem very difficult). Sometimes the absence of a definition of values and expert discussion when deciding on the use of certain elements can lead to an irreversible situation (see, for example, the establishment of a radioactive waste repository in the Bratrství mine).

From the implemented research, it is then possible to synthesize several general findings related to both the theoretical and application level of geographical research. At the level of basic research, it has been confirmed that heritage cannot be seen as a static set of artefacts, but it must be seen as a dynamic socio-cultural process that is influenced and conditioned by actors, subjects and interest groups that operate in a certain area of heritage occurrence [

49,

50,

51,

52]. Actors play a key role in the way heritage is handled and tend to pursue their own goals to meet their subjective needs. This behavior is then reflected in the management and use of the heritage, as well as its presentation and interpretation. The public sector considers it the most important to protect heritage, often at the expense of the presentation and transmission of its values and meanings. Private entities see the potential primarily in the commodification of heritage and its use for profit generation. The non-profit sector then very often combines the previous approaches, trying to use the heritage to promote, improve the image, but of course it also tries to protect it. It is essential to investigate the interconnectedness and relationships of these individual sectors, which usually do not act separately, but complement each other or come into conflict. Heritage is a product of the networks mentioned above and the actors, but if these networks are fragmented and do not cooperate, the full potential of the heritage is not used.

The mining heritage holds great potential, which is often underused at a local scale by all stakeholders. The impetus for the development and strengthening of activities can be a change in the state of protection, which in the case of the Krušnohoří/Erzgebirge is an inscription on the UNESCO World Heritage List. However, it is necessary to use this potential. The actual announcement of various higher levels of protection does not in itself bring development (which can be seen, for example, in the existence of the mentioned landscape heritage zone in Jáchymov). It is, therefore, necessary to initiate the activity of residents and institutions after the inscription of the Krušnohoří/Erzgebirge on the UNESCO World Heritage List, which would lead to more sophisticated forms of management of the mining heritage. The inscription on the UNESCO World Heritage List can bring significant economic and social benefits, but these are highly dependent on what steps will follow in the near future. It is necessary to prepare for the upcoming changes in a timely and high-quality manner and not to wait passively for what the future brings. It may happen that due to lack of action, the chance for progress will be missed. The complex of the mining heritage of the Jáchymov region, but also of the entire Ore Mountains, is very extensive and since the management of a UNESCO site is mainly the responsibility of individual local governments, private or interest groups, it is not possible to generalize the situation in the whole region. However, it is important to point out any gaps and shortcomings and to discuss possibilities for improvement. Only in this way it will be possible to achieve a high-quality transmission of (not only) the mining heritage to future generations and thus the preservation of its essence and meaning.

It is evident from the above that heritage is a living and ever-evolving complex that needs to be explored in the longer term. The area of the Krušnohoří/Erzgebirge (and Jáchymov region) has reached an extraordinary level of heritage protection, but in the future, it will be necessary to use the offered potential economically, culturally and socially. It follows that the area may be the target of further research in the future to assess how the inclusion on the UNESCO list will affect the way the area is managed.