1. Introduction

In recent decades, economic globalization has brought about significant changes in regional development possibilities, altering the way multinational corporations (MNCs) and national and local/international institutions interact. These changes required a broader theoretical framework [

1]. The Global Production Networks (GPNs) framework, especially its focal concept of “strategic coupling”, has become a widely used analytical approach for studying regional development in the context of globalization [

2,

3]. With the gradual establishment of awareness of sustainable development, the international community is paying increasing attention to the coordinated development of economic growth, social progress, and environmental protection. Scholars call attention to the environmental and social impacts of global production networks to achieve economic growth as well as social–environmental sustainability [

2], with the fruits of development benefiting more people [

4].

Strategic coupling refers to the intentional integration and interface between regional economies and actors in global production networks [

5]. Previous strategic coupling studies have been lead-firm-centric, but taking a firm as an entry point is not a must [

6]. Entering from the point of workers, consumers, government agencies or social organizations can place more emphasis on the perspectives and experiences of different actors and their agency [

7]. An issue focused on in the strategic coupling literature is “how to establish linkages between local firms and global production networks?”, which refers to the coupling mechanism. From an actor-centered perspective, many studies have examined how different actors and institutions influence strategic coupling processes through active and purposeful interventions [

2], such as different levels of government agencies [

8,

9], international cooperation zones [

10]. However, few studies have focused on the role of civil society (including nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), other social groups, and citizens). In the era of globalization, improved global communications have increased public awareness of corporate economic activities [

11]. Moreover, increasing global connectivity has enabled affected local communities to access the support and assistance of influential international or national social organizations to bargain with mining firms [

12]. While they have established economic ties with local enterprises and won support from national institutions, some MNCs ignore the demands of social actors, causing dissatisfaction and protests from local society, and they face the possibility of decoupling [

13]. The mining industry has been an important area in which civil society has been active due to its complex social and environmental impacts. The fact that many mining projects have been suspended or permanently halted due to social resistance shows the growing power of social actors, represented by local communities, to bargain with foreign companies [

14]. The influence of the strategic intentions of social actors, such as local communities, on the coupling process between mining capital and resource areas should not be ignored [

15,

16].

This study expands the scope of actors considered in existing strategic coupling studies to include local communities and NGOs. This article argues that social actors (represented by local communities and NGOs) in the global production network may have interests conflicting with those of firms on common concerns, such as land use, livelihoods, and environmental impacts, which constitute social barriers to strategic coupling. To illustrate the argument, this study employs a case study of the Letpadaung Copper Mine (LCM) in Myanmar, which was invested in by a Chinese state-owned firm. The LCM project has undergone a dramatic series of protests, shutdowns, and resumptions in the past ten years, providing researchers with a great deal of factual information. Research data were obtained through field visits, interview surveys, and secondary literature collection. The authors went to Myanmar for field research in November 2018 and December 2019 and conducted semi-structured interviews (

Table A1). Secondary sources include corporate social responsibility (CSR) reports, NGO research reports, government investigation reports, and media news about the LCM project from 2012 to 2020. It should be noted that due to the double impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and the coup in Myanmar in 2021, LCM started a semi-shutdown in 2020 and was completely shut down in early February 2021. Interactions between various actors surrounding the project’s production activities have decreased. Therefore, the case study focuses on copper production activities from 2010 (when the project cooperation agreement was signed between China and Myanmar) to 2020.

The remainder of the article is organized as follows. The next section reviews the literature on strategic coupling, especially their perspectives on social actors and the extractive industry, and then develops an analytical framework of social barriers in the global production networks. The third section begins with a brief introduction of the LCM and the formation of social barriers. Taking land acquisition and environmental impact, the key issues that constitute social barriers, as examples, this article reveals the bargaining process involving firms and the Myanmar state, NGOs, and local communities at multiple scales. The final bargaining outcomes and coupling results will also be presented. The final section concludes and discusses issues that require further research.

3. Strategic Coupling in the Presence of Social Barriers: The Case Study of the Letpadaung Copper Mine

3.1. LCM and Its Construction Process

LCM in Monywa Township, Sagaing region, Myanmar, is the largest hydrometallurgical copper project in Asia. In June 2010, Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao and Myanmar President U Thein Sein jointly witnessed the signing of the production-sharing agreement. Myanmar Economic Holding Limited (MEHL), which has a large-scale mineral production license, was responsible for land acquisition; and the Chinese firm, Wanbao was responsible for investment, development, and management of the project [

43]. MEHL and Wanbao owned 51% and 49% shares of their project products, respectively.

In March 2012, the Letpadaung copper project began, and in June, hundreds of villagers besieged the camp [

44]. Between 3 March and 15 November 2012, 124 incidents of obstruction, verbal abuse, threats, vandalism, and demonstrations occurred [

45]. Following a series of clashes, Myanmar suspended the Letpadaung project and set up an investigation committee headed by Aung San Suu Kyi in December 2012 for a comprehensive evaluation of the project. In March 2013, the investigation committee recommended the continuation of the project, but highlighted further improvements in profit-sharing, land acquisition and compensation, and environmental protection.

Against this backdrop, China and Myanmar resigned their cooperation agreement in July 2013. The state-owned No. 1 Mining Enterprise (ME1) participated in product sharing on behalf of the federal government. Under the new cooperation framework, ME1 held 51% of the shares, while Wanbao and MEHL held the remaining 49% [

43]. Upon recommendation by the investigation committee, the LCM was finally resumed in January 2015 through the continuing efforts of all the parties involved. In March 2016, the project was completed and put into production. In 2018, the output of copper cathode reached 100,000 tons, achieving the design capacity.

3.2. Social Barriers in the Letpadaung Copper Mine

Wanbao negotiated and coordinated with actors such as the Myanmar state, local communities, cooperative enterprises, and NGOs around a range of issues, including land acquisition, environmental protection, the relocation of pagodas, the resettlement of new villages, and the livelihoods of villagers who lost their land. The differences in demand between firms and social actors on these issues constitute social barriers that affect the coupling of MNCs with local assets. In particular, land acquisition and environmental impacts are the root causes of all controversial issues [

46]. This study uses land acquisition and environmental impact as examples to explain the formation of social barriers, the bargaining process between actors, and the coupling results achieved. Although land acquisition and environmental impacts mainly occur at the local community scale, extrafirm actors at other scales are also involved in bargaining over these disputes. They have an impact on the local community scale, so it is also necessary to understand their preferences. These actors have different interests and goals, and play different roles in the bargaining process.

Copper production is limited by geographical location. The hydrometallurgical process of copper refining requires a large area of land, including the mountain containing ore deposits, heap leach fields for ore stockpiling, and drainage fields for waste soil. The availability of sufficient land is directly related to whether the copper mine can continue to produce and generate economic benefits. On the other hand, the land is essential capital for villagers’ livelihoods. Therefore, land acquisition is vital for the “survival” of Wanbao and the local community. Because of differences in living conditions and sources of livelihood, villagers’ views on the copper mine project were diverse. There were two main types of demands from villagers who opposed land expropriation: (1) higher land compensation standards, and (2) recompense for the loss of their livelihoods after the state expropriated of farmland [

47].

Wanbao took over the project during a democratic transition, when civil society became more active in political, economic, and social development. During the transition, the elected government preferred that companies consult with local communities to maintain social stability. NGOs advocated that the government strengthen its supervision of the companies, that the companies comply with laws and regulations, and respect the legitimate rights of villagers on the land. The support of the elected government and NGOs increases the space and opportunities for local communities to bargain with companies, thus giving villagers a greater opportunity to realize their intentions.

Regarding the issue of environmental impact, the difference between actors’ preferences is rooted in Myanmar’s inadequate regulatory system regarding environmental conservation. Myanmar introduced the Environment Conservation Law in 2012, and a revised Mining Law in 2015 that stipulates that feasibility studies should include environmental and social impact assessments (ESIA) and procedures in 2016. However, when Wanbao signed a cooperation agreement with Myanmar partners in 2010, there were no corresponding national standards to follow. The transition from a military government to a democratically elected one in 2010 triggered many changes in the institutional environment. In the face of such institutional uncertainty, actors demonstrated preferences for the standards they chose to follow—the ones that benefited them the most.

Wanbao representatives stated that the company took over the project from Ivanhoe, and initially thought it could follow the ESIA report completed by Ivanhoe in the 1990s without a reassessment (Interviews C1, C2). Instead, communities and NGOs argued that Wanbao invested in a new project for which the ESIA report from Ivanhoe was no longer applicable. Moreover, the social and environmental conditions in the affected areas have changed considerably over the previous decade. The company needed to reassess the project’s potential social and environmental risks (Interviews N1, V1, and V2). In addition, during Ivanhoe’s operation period, villagers in the local community found environmental problems, such as acid leakage and heavy metal pollution. Villagers therefore became more disapproving of the ESIA during Ivanhoe’s time and expected Wanbao to take practical environmental protection measures to reduce its negative impacts (Interview N4). NGOs believe that in the absence of a perfect legal system, companies should follow international standards and assess the environmental and social risks of copper mining projects. As for the state, one of the first areas assessed by the investigation committee was whether the project had been implemented according to international environmental protection standards.

3.3. Actors’ Strategy: Multi-Scale, Multi-Participant Bargaining

The signing of the cooperation agreement coincided with a political transition in Myanmar, which led to significant changes in the institutional environment faced by the company. Moreover, owing to its complex historical background and social environment impact, LCM attracted the attention and involvement of actors at different scales. The actors involved in this production activity include Wanbao, MEHL, ME1, the Myanmar government, civil society organizations, and residents of the surrounding communities (

Figure 2).

3.3.1. Firm

The mining rights of LCM were initially held by ME1, a state-owned enterprise under the Ministry of Mines (later reorganized to form the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Protection [MNREC]). Before the democratic transition, the military government transferred mining rights from the Ministry of Mines to MEHL, a military-controlled enterprise. Therefore, foreign investors were forced to cooperate with MEHL to obtain the mining interest of LCM. Wanbao Mining is a young, global company backed by a large Chinese state-owned enterprise, which has the expertise, involvement in the entire mineral industry chain, and strong financial strength. This constituted the strategic resource base for Wanbao to exercise its bargaining power when negotiating with the host country.

After years of competition with several resource companies including Newmont Mining, Gold Field, and BHP Billiton, Wanbao acquired a cooperative right to develop the LCM.

(Interview C2)

According to the 2010 cooperation agreement, MEHL was responsible for acquiring mineral rights and negotiating with local communities to deal with the issues of land acquisition, compensation, and resettlement. However, Myanmar partners’ lack of capacity to properly handle their share of the work had a significant impact on the project’s progress. Wanbao offered to communicate with the villagers, but MEHL refused—it was not Wanbao’s responsibility or obligation to handle community relations according to the contract, and MEHL warned that it would be personally dangerous to enter the village (Interview C4). As a result, Wanbao began negotiating with MEHL and was not allowed to enter the community on a large scale or communicate directly with villagers until 2014.

3.3.2. Myanmar State

The state plays a role in the global mining production network mainly in two ways: as an operator (generally operating as a state-owned enterprise entity, such as ME1), and as a regulator, overseeing taxation, access to mineral resources, health, safety, and environmental issues [

20]. The investment in LCM coincided with a period of transition in Myanmar that saw an intensive restructuring of laws related to mining activities, such as mining, environmental conservation, and land laws (

Table 1) [

48,

49]. Prior to 2011, there were 73 laws and policies related to land governance in Myanmar, and the legal and institutional framework for land management was fragmented, complex, and outdated [

50]. Legal refinement represents an adjustment to the goals pursued by the state in terms of economic and social development. This also implies a change in the constraints MNCs face when conducting economic activities in Myanmar over time, which may lead to changes in their relative bargaining power in the network.

In March 2013, the investigation committee released a report and made detailed recommendations for corrective measures. These recommendations have largely limited the scope for subsequent decisions by the company and have helped the state achieve its strategic interests. To implement the 42 recommendations of the report, the investigation committee reconstituted the Implementation Committee for the Investigation Report of the Letpaduang Copper Mine Project, which was subsequently transformed into a joint management committee with representatives from all stakeholders to continue monitoring and coordinating LCM. As the provincial government where the project was located, the authority and responsibility of the Sagaing regional government were closely related to mining activities, including employment, tax revenue, the supporting infrastructure invested, and the impact on the surrounding ecological environment. The chief minister of Sagaing appointed two provincial ministers as representatives to form a joint management committee, with ME1 and MEHL to guide the operation and management of LCM. The committee meets regularly and is an important platform for dialogue and institutional coordination between the interests of various actors.

Overall, in the process of institutional change, the role of the Myanmar state has shifted from being a more singular corporate partner to one of regulation, oversight, and cooperation. The government has imposed more constraints on MNCs and provided civil society with more opportunities for voice, communication channels, and the possibility of changing policy.

3.3.3. NGOs

Myanmar’s democratic transition has promoted the development of NGOs in Myanmar, creating a suitable institutional environment for NGOs to participate in decision-making on local affairs and defend the rights and interests of residents. The controversial events arising from the Letpaduang copper project, which involve environmental, community, and human rights issues, have attracted the attention of many NGOs. NGOs, including international and local, often function as connectors between different scales.

Hundreds of international NGOs are active in Myanmar. Most come from Western countries [

51]. They are well funded and mainly engaged in social welfare and human rights advocacy. International NGOs provide funding and capacity-building support to local NGOs in Myanmar, and some are directly involved in social and environmental impact studies and advocacy for copper mining projects. Some organizations do not have a branch office in Myanmar, so they work with local organizations to complete the corresponding research and advocacy. In the case of LCM, one NGO donated 500,000–1 million kyats per year to villages near the mine to purchase utility equipment such as power generators, and funded the organization of skills training courses (Interview V1). The Justice Trust, an international NGO that supports national efforts to advance rule of law and human rights, has partnered with a local Myanmar NGO Lawyers Network to conduct research on villagers’ land rights issues in the LCM project. In 2013, the two NGOs jointly published their

Report of Evidence Regarding Controversies at the Letpadaung Hill Copper Mine Project [

52]. The NGOs are close to villagers’ needs and provide social services, earning the trust of residents—they have not only provided training, coordination, and communications support for community protests, but also have published research in multiple languages to speak out in the international community, amplify the LCM controversy, and exerting strong and sustained pressure on the company from multiple angles.

There are also many active community-based organizations (CBOs) in Myanmar. CBOs are rooted in local communities, usually arising from specific social and environmental issues, with members coming directly from local villagers. Therefore, the organizational goals of CBOs are focused more on the interests and demands of villagers, such as their economic, health, and faith needs. Most CBOs are unregistered, informal, and loosely organized, and such organizations may disband when issues are addressed (Interview N3). In October 2012, with the participation and support of environmentalist and student groups, villagers from communities surrounding the copper mine in Letpadaung joined together to form the 26-member Letpadaung Salvation Committee to urge a complete halt to the copper project and proper protection of Letpadaung Mountain [

53].

3.3.4. Local Community

The surrounding communities are the main groups affected by mining activities. LCM covers an area of 6964 acres (the project originally planned to acquire 7687 acres of land. However, later, Wanbao returned 903.74 acres of land (including 294.75 acres of agricultural land, 42.66 acres of road land, 20.33 acres of irrigation canal land, and 546 acres of environmental land), as recommended by the investigation committee report. Hence, the actual area of land acquired was 6964 acres). It required the relocation of 441 households from four nearby villages and the use of more than 6200 acres of farmland from more than 30 villages. Approximately 70% of the villagers nearby depend on farming and seasonal farming for their livelihoods [

54]. Land acquisition would not only cause some villagers to leave their homes, but would also deprive them of their livelihood. Surrounding communities are also the main bearers of negative environmental impacts caused by mining operations such as ecological damage, and soil and water pollution.

Under the cooperation agreement signed in 2010, MEHL was responsible for land acquisition, while Wanbao was not allowed to communicate directly with villagers. Due to the lack of transparency in the distribution of land acquisition compensation by the MEHL, many problems occurred, such as reduced and delayed payment of compensation, which made villagers quite dissatisfied—even enraged. The failure to properly resolve issues including compensation for land acquisition, relocation and resettlement, livelihoods of displaced villagers, and environmental protection has led to an increasing number of villagers resisting the copper project [

55]. Hundreds of villagers began the first wave of protests in June 2012. With the support of some NGOs, a much larger mobilization broke out in early September 2012, with about 5000 villagers protesting at the mining site. The protests continued to rise from local communities to higher scales, with the support of several social groups, quickly raising public attention to the copper project. In November 2012, protests spread to major cities such as Yangon and Mandalay, and demonstrations were held in front of the Chinese embassy in Myanmar. Protests at the mine continued to escalate as hundreds of protesters occupied the mining operation area. On November 29, the Myanmar government forcefully dispersed the protesting crowds at the camp, injuring some villagers and monks [

56] and making the LCM project internationally controversial. Finally, LCM was forced to stop its construction completely.

LCM resumed on a low-profile basis on 3 October 2013. However, nearly half of the land in the mine area involving relocation and land compensation remained unavailable, as some local villagers did not fully accept their land compensation as planned. The local communities refused to relocate, occupied camps, obstructed construction, or cut off roads, making it impossible to continue production activities at the mine site. Wanbao was forced to adjust its strategy to resume economic activities, as it faced economic losses after huge investments turned into high sunk costs. “We had already invested several hundred million dollars in the construction according to the contract, and we realized that our partner was not capable, so we had to solve the problem ourselves” (Interview C3).

Chinese firms have always worked exclusively with the Myanmar government in the past, ignoring the interests of other social actors. This time, local communities had access to land resources that companies desperately needed and, therefore, had relatively high bargaining power. Wanbao learned the villagers’ demands regarding land acquisition through household visits, the selection of village representatives, and village meetings, then implemented them one by one.

Table 2 summarizes the actors’ roles in the network, the sources, and the scale of their bargaining power. These strategic resources and constraints will change over time; for example, trust in NGOs may decline as public perceptions change and access to land resources owned by community residents may diminish as land acquisition proceeds.

3.4. Coupling Results

3.4.1. Compensation for Land Acquisition

A large part of the local villagers’ dissatisfaction with the land acquisition was because they did not receive compensation that matched the value of the land, and the NGOs and CBOs also argued that the companies did not respect the villagers’ legal rights to the land. In April 2011, the firm paid land compensation to villagers who lost their land. When determining the compensation rate, the firm compared the land compensation rate required by law at the time (12–20 times the land rent, about MMK 5–80) with the crop compensation rate (three times the villagers’ crop income, about MMK 520,000–555,000) and found that the latter was much higher. Hence, the firm finally settled on crop compensation instead of land compensation. It was marked as “received compensation for seedlings” in the agreement, which was questioned by villagers and NGOs. Local villagers said they only received compensation for crops and not for land. Some villagers felt that the company did not explain clearly when paying compensation, and deliberately confused compensation for seedlings with land, which was not transparent enough and increased their dissatisfaction with the company.

After 2013, Wanbao increased its compensation standard and made two more rounds of land compensation payments in accordance with the corrective recommendations of the investigation committee. As of March 2019, Wanbao had made three rounds of land compensation payments, for a total of MMK 12.2 billion (about USD 8 million), guaranteeing that villagers receive compensation for land acquisition in line with market value. Land compensation has been accepted by the majority so far.

3.4.2. Sustainable Livelihoods for Displaced Villagers

Another primary demand of the local villagers regarding the land acquisition was a new way for them to sustain their livelihood after losing their farmland. The investigation committee also proposed providing more jobs for villagers. Temporary land compensation, relocation allowance, and other subsidies cannot sustain villagers’ livelihoods overall, and the company should create more employment opportunities for villagers. By the end of November 2013, Wanbao had invested more than USD 1 million in infrastructure improvement projects. However, villagers believed that there was a misalignment between their actual needs and the company’s “social responsibility” actions [

55].

We don’t care about schools and hospitals. Job opportunities are the top priority for us, most of the time we ask for jobs, and there are still some difficult households inside the village just because they don’t get jobs... Many students graduate every year, and I hope that the copper mine will add more jobs in the future.

(Interviews V1, V2)

Although these projects were important, corporate efforts to build community development projects did not address the villagers’ urgent livelihood needs. This led some villagers to resent the company, be uncooperative in discussing and communicating their needs face-to-face with the company, and persist in their opposition to the copper mining project [

55]. Some social activists took advantage of the villagers’ defiant sentiments and continued to launch protests among the villagers (Interviews V1 and W3) and even kidnapped Wanbao employees in May 2014, leading to the villagers’ deaths [

57].

Wanbao realized that it was essential to evaluate what makes a social responsibility program effective. Only when Wanbao met the villagers’ actual needs did they gain support from locals. Local villagers lack awareness and the ability to manage their funds. Most use compensation money to pay for daily expenses instead of investing in their livelihoods, which does not bring sustainable income to their families. When the compensation money is exhausted and job opportunities remain uncertain, villagers may make new demands on the company. It also highlights the necessity of addressing the issue of sustainable livelihoods for villagers for companies to move forward with land acquisition.

To meet the villagers’ needs for a livelihood, Wanbao took two main actions. First, it launched a Contribution Plan. Each family can obtain one to three jobs, depending on how much land was expropriated. If they are not employed, each household can still receive a corresponding subsidy according to the standard. The subsidy is paid every six months to ensure that the basic needs of landless farmers are met while waiting for employment. As of June 2020, 1021 households (91.13%) of landless villagers had accepted the job grant program. Second, it created as many job opportunities as possible. In response to local villagers’ concerns about working in the mine, Wanbao purposely set up many low-threshold employment positions, such as cooks, cleaners, and laundry workers (Interview W2). Simultaneously, employee skills training was provided to improve villagers’ employability. As of June 2020, LCM and subcontractors employed more than 6100 Myanmar workers, most of whom were from surrounding communities [

58]. Wanbao pays its employees an average salary of USD 400/month, far above the original local income level.

Compared to industries of the same size, the mining industry has less labor demand. Therefore, apart from the localized employment strategy, Wanbao launched the SME (small and medium enterprise) program to support local villagers in developing SMEs such as transportation, quarrying, and construction teams. The SME project created diversified employment opportunities and helped displaced villagers gain new sources of livelihood. Currently, the SME project has helped nearly 900 villagers to find jobs.

Some NGO groups have accused Wanbao of addressing the livelihoods of only a small percentage of villagers in the affected communities. They argue that copper production has affected 25,000 villagers, yet Wanbao has provided only a few thousand jobs. Most of the remaining villagers still face livelihood problems and are forced to leave their hometowns to find work [

44]. This study believes that a firm’s ultimate purpose is always to realize its economic interests. To gain the support and permission of local villagers, companies must address the urgent livelihood needs of the residents of the affected communities. It is a trade-off between addressing the jobs of tens of thousands of villagers and the economic benefits. After much communication and coordination, Wanbao addressed the livelihoods of landless villagers based on the degree of impact on the local communities. For example, the villagers of the four relocated villages within the mine area, who are the most affected by the copper mine, enjoy priority employment rights. Those in other areas will be gradually addressed. According to the CSR reports released by Wanbao over the years, the number of jobs created for local villagers gradually increased as the copper mine project progressed and SME projects developed.

The resolution of livelihood issues has eased the relationship between the company and the local villagers. The Letpadaung project received support and approval from most villagers. “The villagers’ attitude has changed a great deal, and now it is useless for some organizations to come to the nearby villages, because the surrounding villagers no longer follow their lead” (Interviews C1, C3, and C4).

3.4.3. Environmental Conservation

The different outcome preferences for the issue of environmental impact are rooted in the uncertainty of the system. Faced with pressure from various actors, Wanbao followed international standards in conducting ESIA and developing an international standard environmental management system based on the recommendations of the investigation committee to rectify the situation. The ESIA of LCM resolved more than 600 technical issues and was formally approved by the Myanmar government in March 2015, after full communication and coordination with 33 villages in the past 20 months. This is the first ESIA report of a large-scale project officially approved by the Myanmar government. It not only serves as a guide for implementing environmental protection and community relations maintenance during the construction and operation phases of the project, but also sets the standard for ESIA regarding large-scale projects in Myanmar.

Moreover, Wanbao has developed a complete health, safety, security, and environmental protection (HSSE) management system to make the project go smoothly. In 2017, the environmental management system was successfully audited and certified by SGS. In January 2018, MNREC issued an environmental conformity certificate to the company. Wanbao also set up a pit closure fund in accordance with international standards to implement the principle of simultaneous mining and protection, to minimize the environmental impact from exploration to pit closure. According to the pit closure plan, once the project enters operation, Wanbao will contribute USD 2 million annually to the fund account as an environmental management guarantee fund for continuous reclamation, vegetation restoration, and pit closure. By the end of 2019, 478,000 square meters of reclamation work had been completed. Many environmental measures taken by Wanbao have been recognized by the community, NGOs, and the state.

We have built a complete monitoring system for water quality, noise, air, and vibration. Monitoring points were set up at the project site as well as in the surrounding communities. These monitoring data can fully demonstrate the environmental conditions of the surrounding communities. NGOs who originally claimed that copper production would damage the environment no longer resist once they saw the data.

(Interview C3)

Wanbao stated that many initiatives have been included as standards in Myanmar’s new mining laws and regulations (Interviews C2, N2), as evidenced by the new amendments to the mining law [

59].

3.4.4. Multi-Win Inclusive Coupling

Since the signing of the cooperation agreement, the Letpadaung copper production network has gone through a democratic transition in Myanmar, encountering difficulties such as public protests and project stoppages. Wanbao has bargained with the state, NGOs, and local communities at different scales to realize their respective interests, and finally achieved strategic coupling with localities. In the early stages, Wanbao only negotiated with the state, ignoring the interests of other social actors, especially the demands of the affected local communities on the issues of land acquisition and environmental impact. After fully realizing the importance of social actors in the production network, Wanbao began actively fulfilling its social responsibility and achieved an inclusive multi-win coupling (

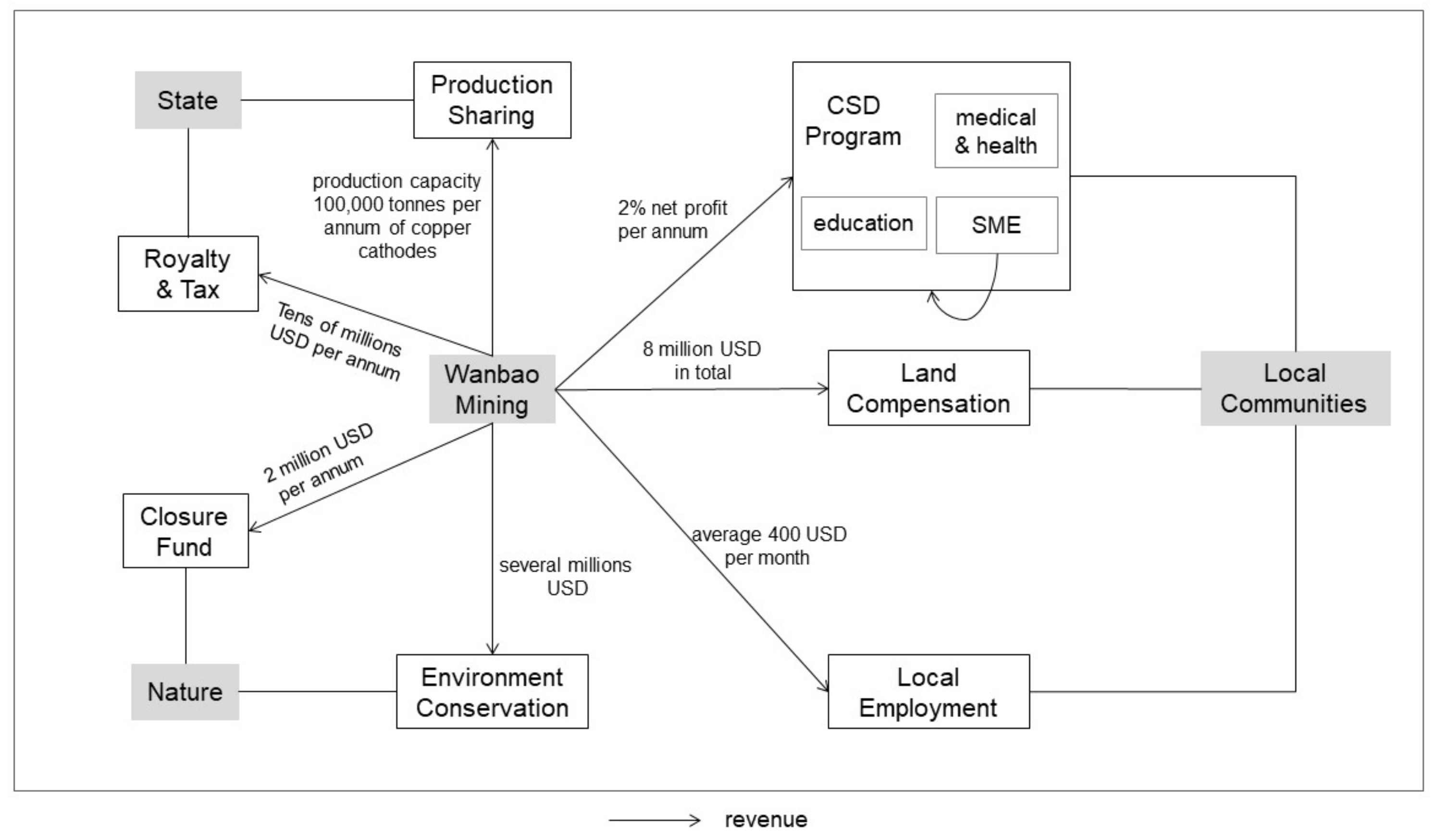

Figure 3).

For Wanbao, the successful construction and commissioning of LCM meant achieving economic goals. Wanbao invested hundreds of millions of dollars in costs at the beginning of the mine construction shutdown, losing approximately USD 2 million each month. After a successful start-up, LCM would be able to produce 100,000 tons of copper cathodes per year, and the copper project is currently making profits in hundreds of millions of dollars (Interview C1, C4). “Despite spending some money (on social responsibility), there are still significant economic benefits for the copper project, and it is worthwhile to invest even USD 10 million as resource projects will develop in the same place for decades” (Interviews C4). For Myanmar companies, MEHL can share ten million dollars of profit per year without bearing the costs. More than 20 local Myanmar companies were also involved in constructing the copper mine, reaping huge economic benefits (Interview J1).

For Myanmar state, the successful coupling of LCM is beneficial for maintaining relations between China and Myanmar and increasing other foreign investors’ confidence. In terms of direct economic benefits, the Myanmar central government receives a 4% royalty and a 15% income tax, while a 51% share of the copper product goes to ME1, representing the national interest, with a cumulative value of hundreds of millions of dollars. The direct benefit to the Sagaing provincial government is the personal income tax paid by the project employees. In terms of indirect economic benefits, the LCM project will bring a steady stream of economic value to Myanmar by creating several jobs, enhancing the employment skills of local villagers, and driving the development of SMEs.

For some NGOs, the goals advocated by these organizations, such as improving the legal and regulatory systems, environmental protection, and respecting the legitimate rights of villagers, have been achieved. For example, Myanmar revised the Mining Law, introduced the Environment Conservation Law and the ESIA procedure. The firm has developed an environmental management system in accordance with international standards, and measures such as zero discharge of sewage and innocuous treatment of waste rock have significantly reduced the negative environmental impact of the mine. The ecological environment around the mine has been greatly improved compared with Ivanhoe’s operation period [

60]. Data analysis of remote sensing quantitative monitoring of the ecological environment of LCM shows that Wanbao has done a good job of preventing ecological risks, which has reduced the ecological occupation of mine development and its impact on the surroundings. Wanbao has done an even better job at protecting water resources, as industrial waters remain concentrated in the mine area without polluting the surrounding waters [

61]. Therefore, the NGO’s advocacy contributed to reducing the value destruction of the copper production network.

For local communities, the villagers have gained new sustainable livelihoods, their incomes have improved significantly compared to before, as have their living conditions. Wanbao has also established a community sustainable development (CSD) project fund to support 33 nearby villages, with an annual investment of US$1 million during the construction phase and 2% of net profits (approximately US$2 million) during the operational phase. As of June 2020, USD 12.1 million had been invested in community development projects. The CSD fund was set up to enable different groups in the surrounding communities to enjoy the fruits of copper mining development equally, and to achieve inclusive growth. Investments in education and healthcare will promote social capital development overall, avoiding overreliance on mining development and contributing to sustainable local development.

4. Conclusions

Owing to its complex historical background and social and environmental impact, LCM involves multiple actors—especially extrafirm actors such as the state, NGOs, and local communities, who have a non-negligible influence on copper production activities. Firms and extrafirm actors support or constrain each other, seek to achieve their respective goals through bargaining, and collectively influence changes in the production network of LCM. The findings of this study are as follows.

First, there are social barriers in the coupling process between mining production networks and local assets. The differences in actors’ outcome preferences were particularly evident in land acquisition and environmental impacts, which constituted social barriers affecting the coupling. Residents who were directly affected by the copper mine’s production activities expected reasonable compensation for their land, and sustainable livelihoods for landless villagers. Civil society organizations actively expressed and participated in the deregulated social situation, advocating for stronger government regulation, corporate social and environmental performance supervision, and support for villagers in negotiations and coordination, thus raising public concerns about the LCM. During the democratic transition, the Myanmar government’s outdated legal framework and imperfect governance capacity resulted in the demands of local communities not being adequately addressed at the outset, exacerbating the severity of the corporate–civil society conflict. In such a complex network of relationships, the demands of different actors vary, and are dynamic, unstable, and conflicting.

Second, there is an interplay between bargaining at different scales. Bargaining is inherently spatial, with each bargaining process occurring at a different node in the network. The geographic location and scale of the node determine the range of influence of the bargaining outcomes. Bargaining processes at lower scales occur under the influence of bargaining outcomes at higher scales, and vice versa. The recommendations of the investigation committee were reflected in subsequent mining laws in Myanmar, such as the requirement for companies to submit evidence that they had negotiated with and obtained the consent of local communities on social responsibility when applying for mineral licenses. Even negotiations between companies and area residents may set local precedents that eventually influence legislation at the national level. Previous GPN studies have not yet delved into local community-level analyses, which is one of the contributions of this study.

Based on the above findings, this paper suggests the following recommendations for MNCs. First, MNCs should consider the interests of actors at multiple scales. Enterprises should be fully aware of obtaining support from local communities, especially when the projects tend to have complex social and environmental impacts. Companies should be more active and proactive in the pre-investment stage to understand the demands of affected groups and establish regular communication and grievance mechanisms to respond to the dynamic needs. MNCs should implement CSR programs with an attitude closer to that of local people. Benefit distribution should be fully communicated to all relevant actors to achieve procedural and outcome fairness. Second, take advantage of the correlation between scales. The higher the scale of standard, the greater the scope it applies. When coupling with places where the rule of law is not yet well established, MNCs should follow international standards and norms of social responsibility to minimize social risks in the case of political unrest and institutional reforms in the host country.

Many aspects require further exploration. This article defines three levels of bargaining power, but the third level, in which perceptions can be changed over time, is not clearly reflected in the LCM case. Future research on strategic coupling over a longer period should consider the bargaining power of actors to influence others’ perceptions. In addition, other comparative studies are required to support the theoretical framework proposed here, such as comparing mining production networks in different countries and regions, or comparing the role of extrafirm actors, especially civil society, in different industries.