Planning behind Closed Doors: Unlocking Large-Scale Urban Development Projects Using the Stakeholder Approach on Tenerife, Spain

Abstract

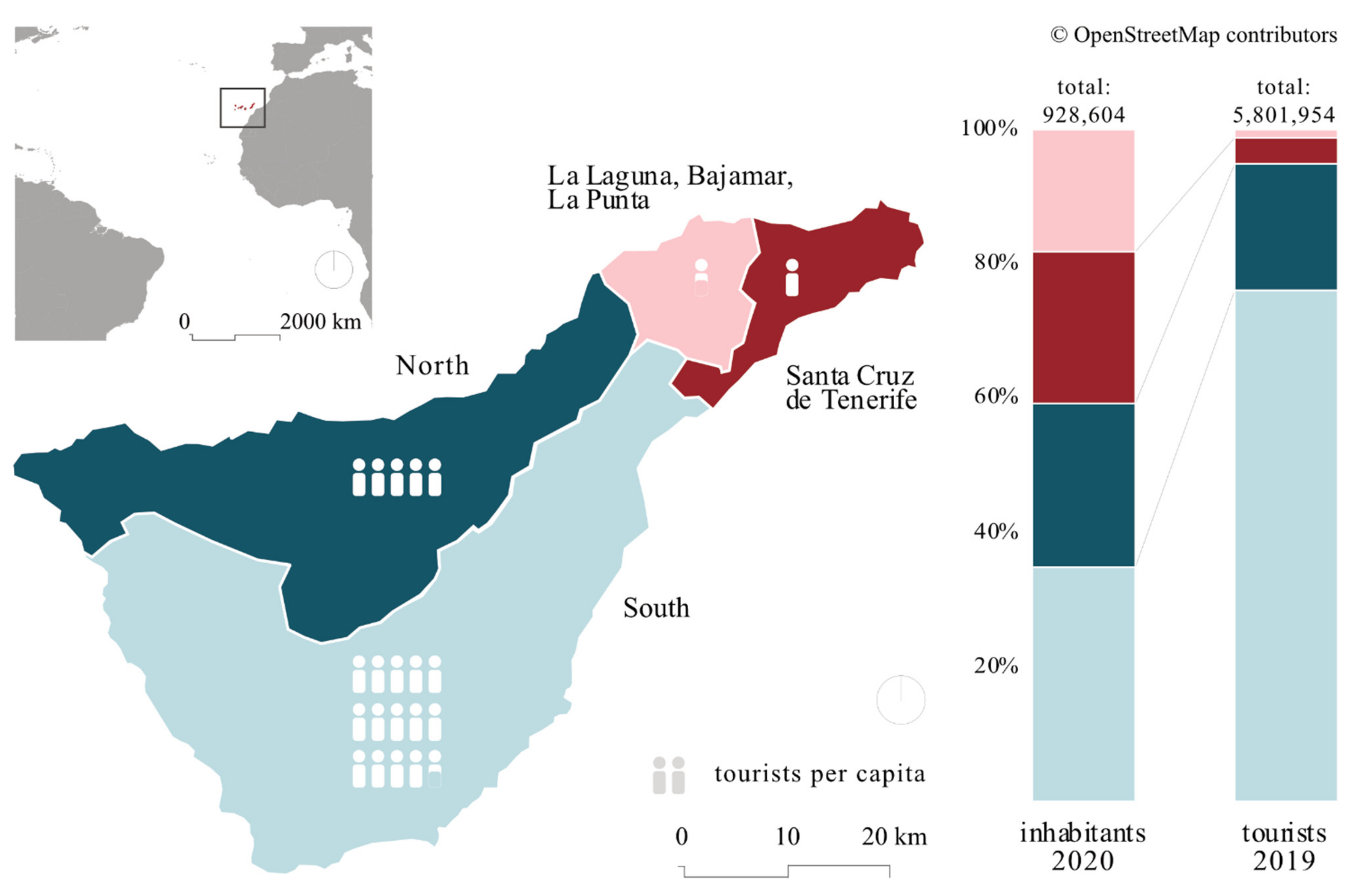

:1. Introduction

2. Tourism and Megaprojects: The Stakeholders’ Perspectives

2.1. Unleashing Tourism through Megaprojects

2.2. Stakeholder Approaches to Megaprojects

3. Method and Material

3.1. Qualitative Interviews as Approach to the Case

3.2. Quantitative Analysis as First Analytical Step

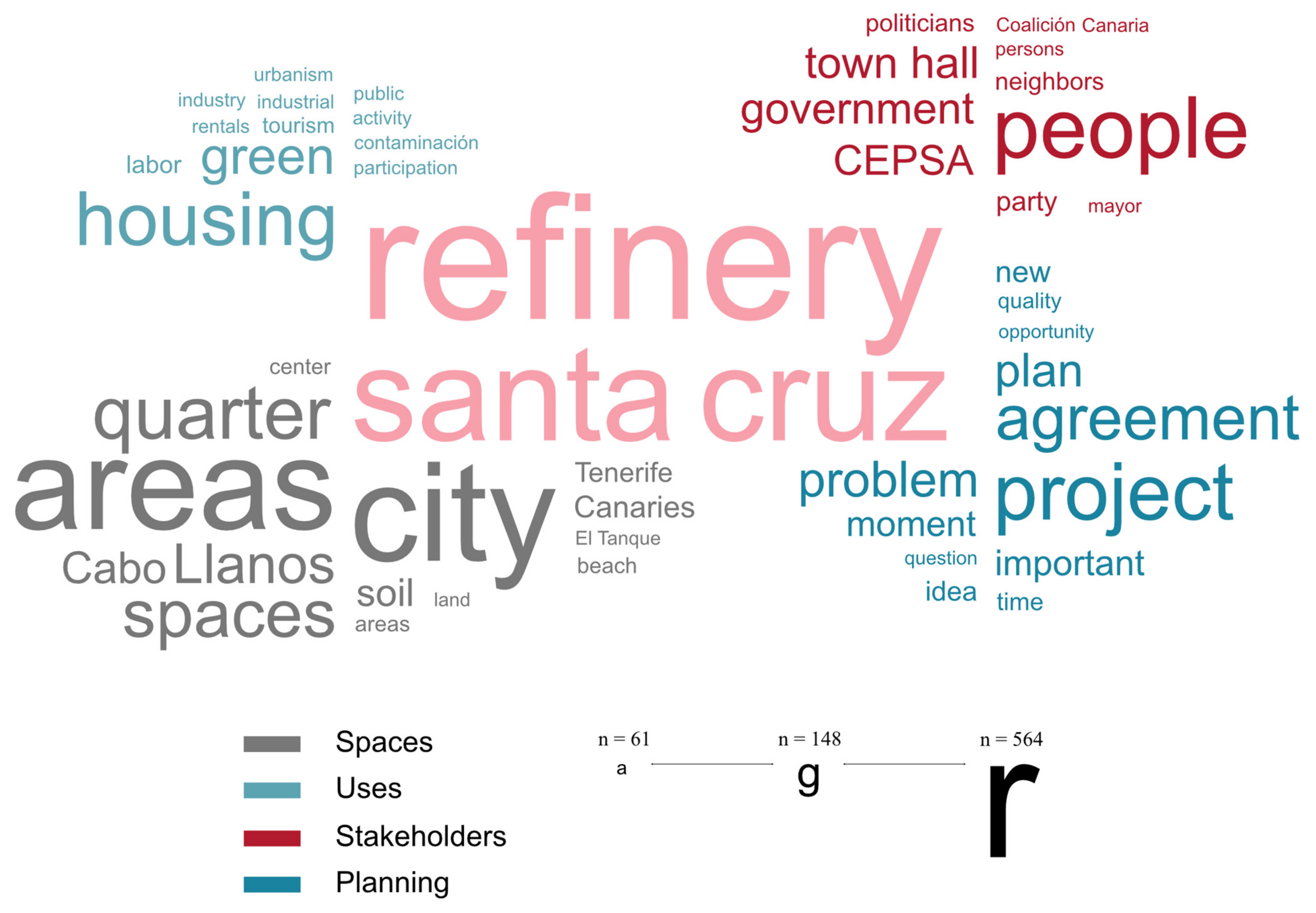

- Firstly, the words cluster around four main topics, namely, space, stakeholders, uses, and planning;

- Secondly, function-related aspects of the project, such as housing or green spaces, were not as present during the conversations as, for example, particular stakeholders or places. Tourism even played a minor role;

- Thirdly, primary stakeholders, such as CEPSA and the town hall, were named very often. However, the society in general, as a secondary stakeholder, gained the most hits;

- Fourthly, with regard to places, terms were used that refer to sites beside the megaproject itself. This is the case for “neighborhoods” in general, but also “center” and “Cabo-Llanos”, which had the most hits of all the surrounding neighborhoods.

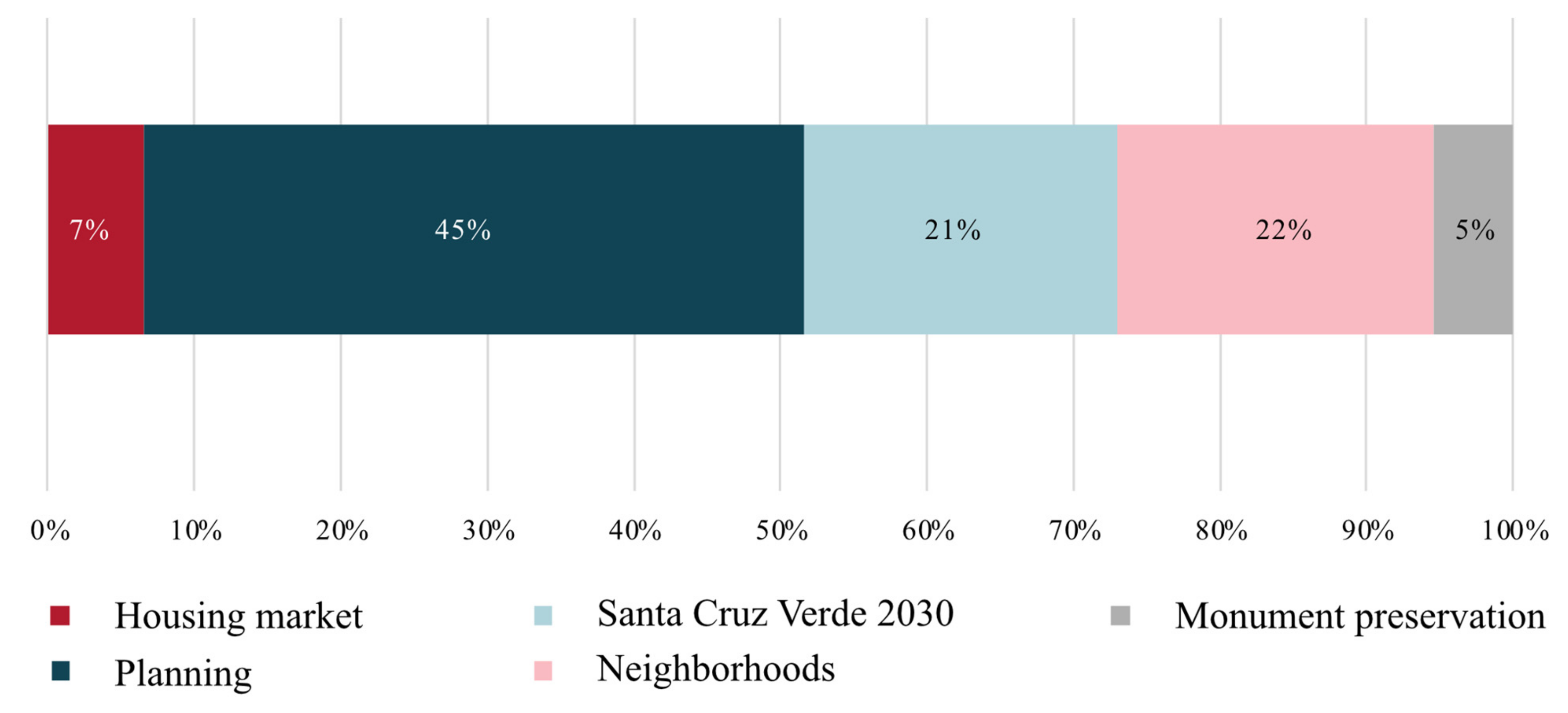

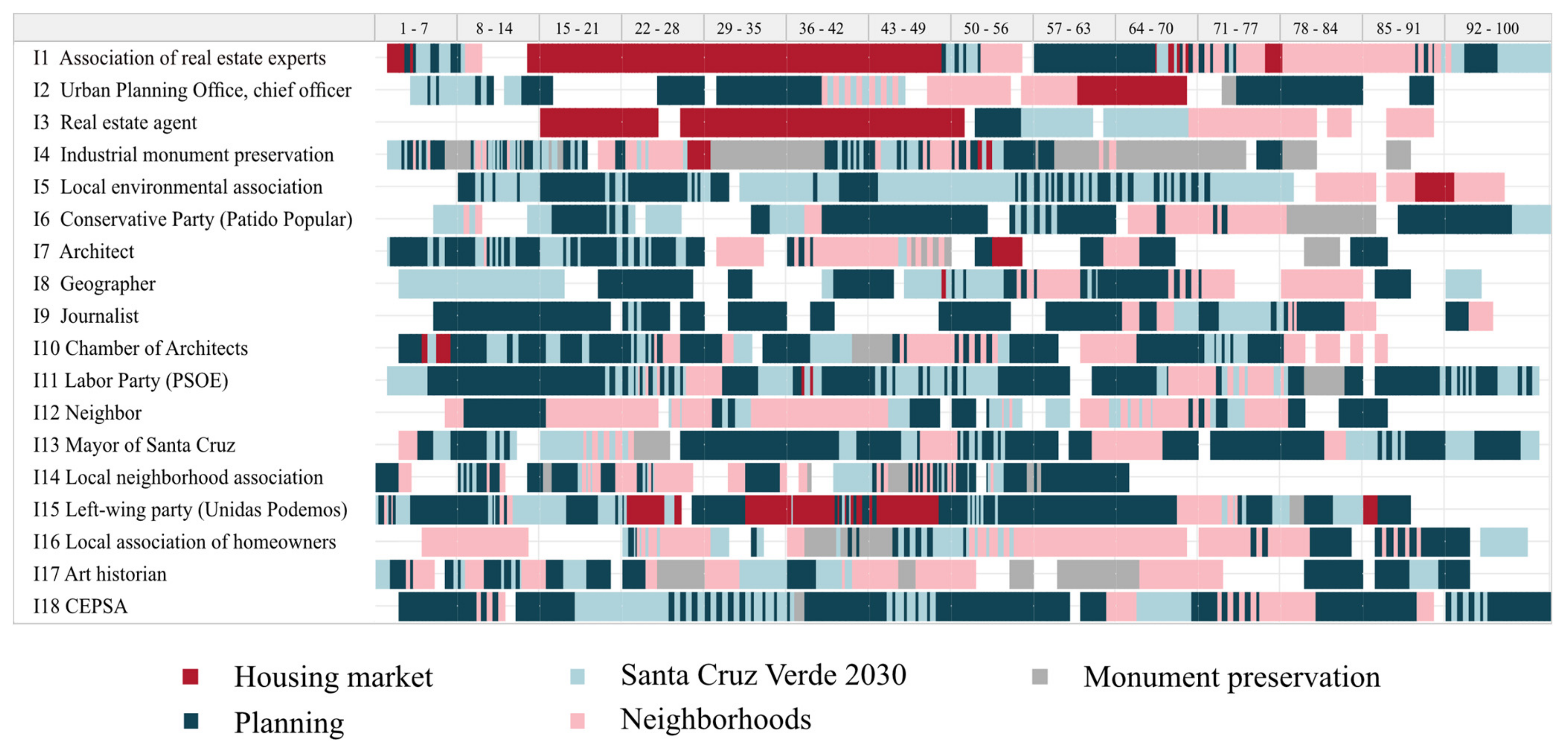

- Firstly, planning (dark blue) and neighborhoods (light red) appeared in every interview, although to a different extent. In most of the interviews, one of these topics was the most dominant;

- Secondly, the discussion of the megaproject itself (contents) varied strongly between the interviews. Surprisingly, the conversations with the primary stakeholders focused less on contents, although I used comparable guidelines. Additionally, there are some longer sections in the transcripts wherein the megaproject concept was discussed in-depth, but it is striking that many interviewees referred to the project along the way (represented by the numerous short light-blue lines);

- Thirdly, Figure 4 shows that some interviews had a higher density of information, such as I1 or I11, while others contained large parts that were not coded because they were not considered to be relevant for this study (I14, I7).

4. Exploring Santa Cruz Verde 2030 through the Stakeholders’ Lenses

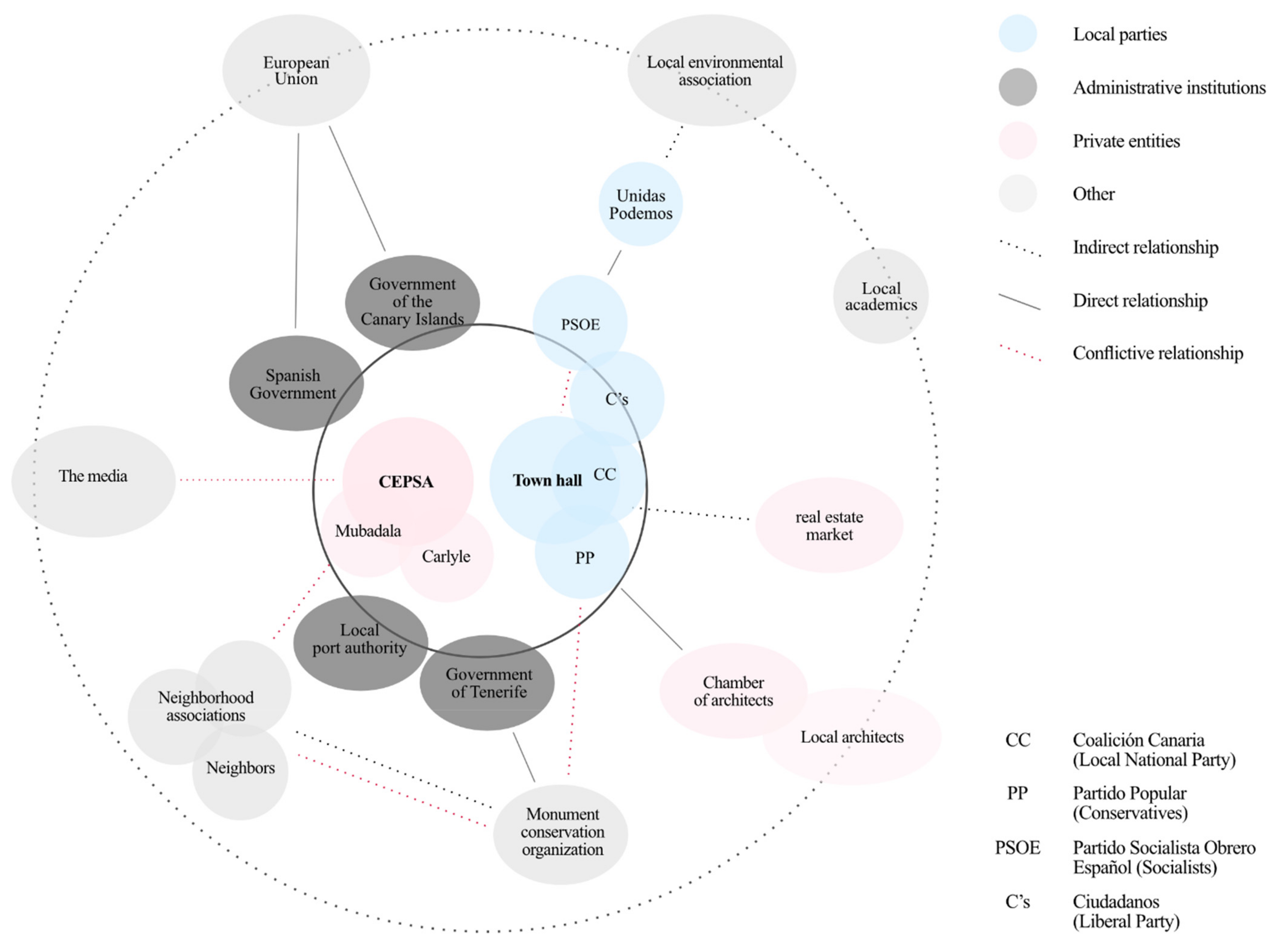

4.1. The Stakeholders and Their Roles

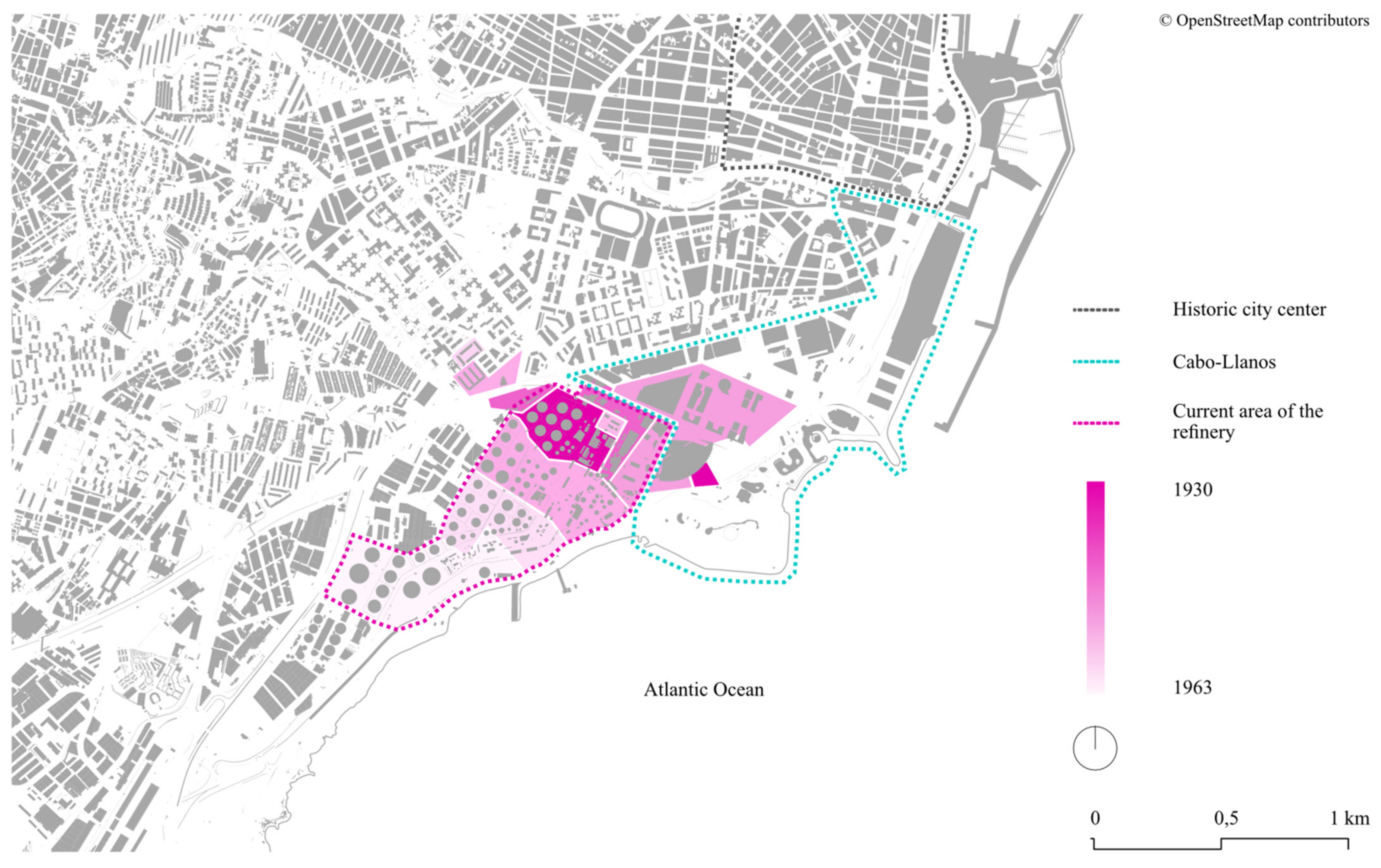

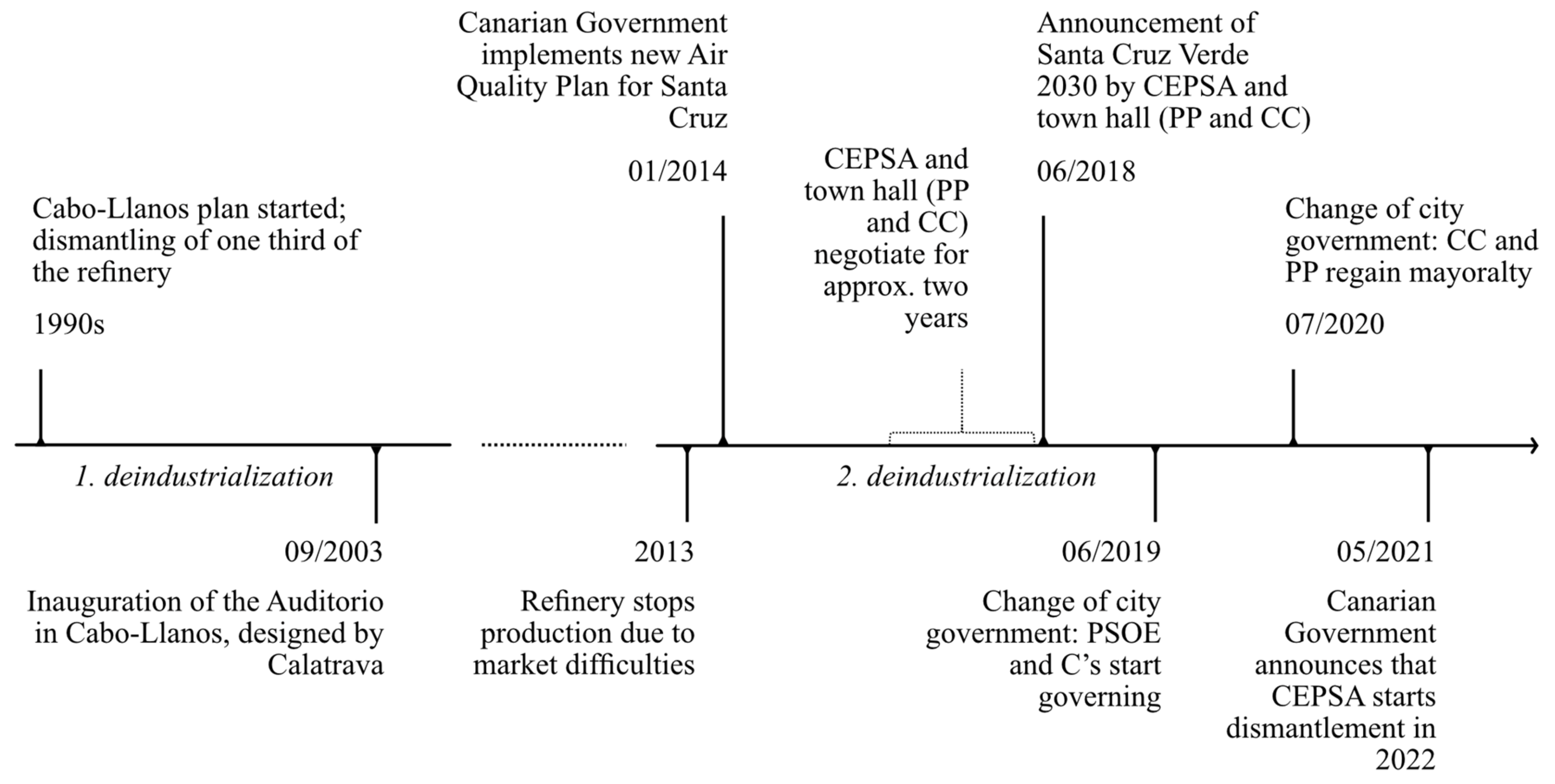

4.2. The Oil Refinery: Moving or Being Moved?

4.3. The Role of Tourism

- Compared to less controversial uses such as housing and green spaces, tourism accounts for a relatively small share—“these 10% [of tourism] do no frighten me” (I1: 59, Real estate association)—although it still accounts for 57,300 square meters. Additionally, for several interviewees, the other functions (housing and green spaces) were more relevant;

- Tourism infrastructure in the megaproject is linked to the demands of the inhabitants. One example is the planned construction of a beach, a project with high prestige that many inhabitants wish to pursue: “Santa Cruz has lost a beach a long time ago […]. Santa Cruz to the sea, I like that” (I12: 81, Neighbor);

- The economic dependency of the island on tourism is obvious, and tourism is linked to economic growth. This is seen as a major reason for why there is no critical discussion about tourism in Santa Cruz (I5: 68, Environmental association).

4.4. Impacts

4.5. Planning the Megaproject: From Hiding to Not Letting Participate

5. Discussion: The Right to Santa Cruz Verde 2030

5.1. A Megaproject—For Whom?

5.2. A Megaproject—By Whom?

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Keul, A. Tourism Neoliberalism and the Swamp as Enterprise. Area 2014, 46, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagermeier, A.; Amzil, L.; Elfasskoui, B. Touristification of the Moroccan Oasis Landscape: New Dimensions, New Approaches, New Stakeholders and New Consumer Formulas. Chang. et Formes D’adaptation Dans Les Espaces Ruraux. 2019. Available online: http://wordpress.kagermeier.de/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Kagermeier-Amzil-Elfasskaoui_Colloque-Ait-Hamza_Tourisme-Oasis-Maroc_26-09-2017.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Burgold, J.; Frenzel, F.; Rolfes, M. Observations on slums and their touristification. Die Erde 2013, 144, 99–104. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco-Romero, A.; Blázquez-Salom, M.; Morell, M.; Fletcher, R. Not tourism-phobia but urban-philia: Understanding stakeholders’ perceptions of urban touristification. Bol. Asoc. Geógr. Esp. 2019, 83, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sequera, J.; Nofre, J. Shaken, not stirred. New debates on touristification and the limits of gentrification. City 2018, 22, 843–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, L. Tourism Gentrification in Lisbon. The Panacea of Touristification as a Scenario of Post-Capitalist Crisis. In Crisis, Austerity, and Transformation. How Disciplinary Neoliberalism is Changing Portugal; David, I., Ed.; Lexington Books: Lanham, MD, USA, 2018; pp. 25–47. [Google Scholar]

- Del Romero Renau, L. Touristification, Sharing Economies and the New Geography of Urban Conflicts. Urban Sci. 2018, 2, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- UNWTO. World Tourism Organization. International Tourism Highlights; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2019; Available online: https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/book/10.18111/9789284421152 (accessed on 11 January 2022).

- Statista. Evolución Anual del Número de Visitantes Internacionales en España de 2006 a 2020, Por Tipo. Available online: https://es.statista.com/estadisticas/474658/visitantes-extranjeros-en-espana-por-tipo/ (accessed on 11 January 2022).

- Bugalski, Ł. The Undisrupted Growth of the Airbnb Phenomenon between 2014–2020. The Touristification of European Cities before the COVID-19 Outbreak. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fainstein, S. Mega-projects in New York, London and Amsterdam. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2009, 768–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majoor, S. Framing Large-Scale Projects: Barcelona Forum and the Challenge of Balancing Local and Global Needs. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2011, 31, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz Orueta, F.; Fainstein, S. The New Mega-Projects: Genesis and Impacts. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2009, 32, 759–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehrer, U.; Laidley, J. Old Mega-Projects Newly Packaged? Waterfront Redevelopment in Toronto. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2008, 32, 786–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordhus-Lier, D. Community resistance to megaprojects: The case of the N2 Gateway project in Joe Slovo informal settlement, Cape Town. Habitat Int. 2015, 45, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Maddaloni, F.; Davis, K. The influence of local community stakeholders in megaprojects: Rethinking their inclusiveness to improve project performance. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2017, 35, 1537–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Millet, D. El Gobierno Local Allana el Camino a la «Mayor Operación Urbanística del País». El Día. 2022. Available online: https://www.eldia.es/santa-cruz-de-tenerife/2022/01/31/gobierno-local-allana-camino-mayor-62129684.html?pimec-source=www.eldia.es&pimec-widget=1&pimec-config=2&pimec-mod=0&pimec-pos=2 (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- ISTAC Instituto Canario de Estadística. Población. Municipios por Islas de Canarias y Años. Available online: http://www.gobiernodecanarias.org/istac/jaxi-istac/tabla.do (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- González Chávez, C.M. Nuevas propuestas arquitectónicas y de equipamiento urbano en el siglo XXI. El futuro de Cabo-Llanos en Santa Cruz de Tenerife (Canarias). Arte Y Ciudad. Rev. De Investig. 2018, 14, 33–64. [Google Scholar]

- García Herrera, L.M.; Smith, N.; Mejías Vera, M.Á. Gentrification, Displacement, and Tourism in Santa Cruz de Tenerife. Urban Geogr. 2007, 28, 276–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayuntamiento de Santa Cruz de Tenerife; CEPSA. Acuerdo de Colaboración Público-Privada para el Plan Santa Cruz Verde 2030. Available online: https://www.santacruzdetenerife.es/scverde2030/fileadmin/user_upload/web/SCverde2030/NotadePrensa26062018.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2019).

- Gonar, H. ‘Santa Cruz 2030’ Supondrá un Ahorro en el Proyecto del Tren del Sur. El Día 2022. Available online: https://www.eldia.es/santa-cruz-de-tenerife/2022/02/09/santa-cruz-2030-supondra-ahorro-62474037.html (accessed on 2 March 2022).

- Hübscher, M. From megaprojects to tourism gentrification? The case of Santa Cruz Verde 2030 (Canary Islands, Spain). Bol. Asoc. Geógr. Esp. 2019, 83, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hübscher, M.; Schulze, J.; Zur Lage, F.; Ringel, J. The Impact of Airbnb on a Non-Touristic City. A Case Study of Short-Term Rentals in Santa Cruz de Tenerife (Spain). Erdkunde 2020, 74, 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INE—Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Número de Turistas Según Comunidad Autónoma de Destino Principal. Available online: https://www.ine.es/jaxiT3/Datos.htm?t=10823 (accessed on 11 January 2022).

- Cheer, J.; Cole, S.; Reeves, K.; Kato, K. Tourism and Islandscapes: Cultural realignment, social-ecological resilience and change. Shima 2017, 11, 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baixinho, A.; Santos, C.; Couto, G.; de Albergaria, I.S.; da Silva, L.S.; Medeiros, P.D.; Simas, R.M.N. Islandscapes and Sustainable Creative Tourism: A Conceptual Framework and Guidelines for Best Practices. Land 2021, 10, 1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armas-Díaz, A.; SaBaté-Bel, F.; Murray, I.; Blázquez-Salom, M. Beyond the Right to the Island: Exploring Protests against the Neoliberalization of Nature in Tenerfie (Canary Islands, Spain). Erdkunde 2020, 74, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hof, D. Home Dispossession and Commercial Real Estate Dispossession in Tourist Conurbations. Analyzing the Reconfiguration of Displacement Dynamics in Los Cristianos/Las Américas (Tenerife). Urban Sci. 2021, 5, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimführ, S.; Otto, L. Doing research on, with and about the island: Reflections on islandscape. Isl. Stud. J. 2020, 15, 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabildo de Tenerife. Cifras Padronales. Available online: https://www.tenerifedata.com/dataset/cifras-padronales (accessed on 11. January 2022).

- Turismo de Tenerife. Indicadores Turísticos de Tenerife. 2022. Available online: https://www.webtenerife.com/investigacion/situacion-turistica/indicadores-turisticos/?filter-year=2019 (accessed on 11 January 2022).

- Open Street Map; Geofabrik GmbH. OpenStreetMap Data Extracts. Available online: https://download.geofabrik.de (accessed on 11 January 2022).

- Füller, H.; Michel, B. ‘Stop Being a Tourist!’ New Dynamics of Urban Tourism in Berlin-Kreuzberg. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2014, 38, 1304–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, D. From Managerialism to Entrepreneurialism: The Transformation in Urban Governance in Late Capitalism. Geogr. Annaler. Ser. B Hum. Geogr. 1989, 71, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fainstein, S.; Judd, D. Cities as Places to Play. In The Tourist City; Judd, D.F., Susan, S.F., Eds.; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA; London, UK, 1999; pp. 261–272. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, E. Authenticity and Commoditization in Tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1988, 15, 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aytar, V.; Rath, J. Selling Ethnic Neighborhoods. The Rise of Neighborhoods as Places of Leisure and Consumption; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Dirksmeier, P.; Helbrecht, I. Resident Perceptions of New Urban Tourism: A Neglected Geography of Prejudice. Geogr. Compass 2015, 9, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voase, R. Creating the Tourist Destination: Narrating the Undiscovered and the Paradox of Consumption. In Tourism, Consumption and Representation: Narratives of Place and Self; Meethan, K., Anderson, A., Miles, S., Eds.; CABI: Kings Lynn, UK, 2006; pp. 284–300. [Google Scholar]

- Sequera, J.; Nofre, J. Touristification, transnational gentrification and urban change in Lisbon: The neighbourhood of Alfama. Urban Stud. 2019, 57, 3169–3189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojeda, A.; Kieffer, M. Touristification. Empty concept or element of analysis in tourism geography? Geoforum 2020, 115, 143–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotham, K.F. Tourism Gentrification: The Case of New Orleans’ Vieux Carre (French Quarter). Urban Stud. 2005, 42, 1099–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachsmuth, D.; Weisler, A. Airbnb and the Rent Gap: Gentrification Through the Sharing Economy. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2018, 50, 1147–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enright, T. The political topology of urban uprisings. Urban Geogr. 2017, 38, 557–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doucet, B.; Van Kempen, R.; Van Weesep, J. Resident Perceptions of Flagship Waterfront Regeneration: The Case of the Kop Van Zuid in Rotterdam. Tijdschr. Voor Econ. En Soc. Geogr. 2010, 102, 125–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hübscher, M. Megaprojects, Gentrification, and Tourism. A Systematic Review on Intertwined Phenomena. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salom, J.; Pitarch, M.; Albertos, J. Desired and undesired effects of the tourism development policy based on megaprojects: The case of Valencia (Spain). Eur. J. Geogr. 2019, 10, 132–148. [Google Scholar]

- Del Cerro Santamaría, G. The Alleged Bilbao Miracle and its Discontents. In Urban Megaprojects: A Worldwide View; Del Cerro Santamaría, G., Ed.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2013; Volume 13, pp. 27–59. [Google Scholar]

- Moulaert, F.; Swyngedouw, E.; Rodriguez, A. Large Scale Urban Development Projects and Local Governance: From Democratic Urban Planning to Besieged Local Governance. Geogr. Z. 2001, 89, 71–84. [Google Scholar]

- Hufeisen, J. Der “Sprung über die Elbe”—Zivilgesellschaftliche Strategien der Teilhabe an Stadtentwicklungsprozessen auf den Hamburger Elbinseln. In Sozialraum und Governance. Handeln und Aushandeln in der Sozialraumentwicklung; Alisch, M., Ed.; Verlag Barbara Budrich: Opladen/Berlin, Germany; Toronto, ON, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, M. Competitive Precinct Projects: The Five Consistent Criticisms of “Global” Mixed-Use Megaprojects. Proj. Manag. J. 2017, 48, 76–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adityanandana, M.; Gerber, J.-F. Post-growth in the Tropics? Contestations over Tri Hita Karana and a tourism megaproject in Bali. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1839–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girma, M.; Singh, M. The Impact of Megaprojects on Branding Ethiopia as an Appealing Tourist Destination. J. Environ. Manag. Tour. 2018, 8, 1733–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocola-Gant, A. Tourism gentrification. In Handbook of Gentrification Studies; Lees, L., Phillips, M., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham/Northampton, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Colomb, C.; Novy, J. Protest and Resistance in the Tourist City; Routledge, Tayler & Francis: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ardura Urquiaga, A.; Lorente-Riverola, I.; Ruiz Sanchez, J. Platform-mediated short-term rentals and gentrification in Madrid. Urban Stud. 2020, 57, 3095–3115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravari Barbas, M.; Guinand, S. Tourism and Gentrification in Contemporary Metropolises. International Perspectives; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Parra, I.; Jover, J. Overtourism, place alienation and the right to the city: Insights from the historic centre of Seville, Spain. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 158–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torkington, K.; Perdigão Ribeiro, F. Whose right to the city? An analysis of the mediatized politics of place surrounding alojamento local issues in Lisbon and Porto. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plichta, J. The co-management and stakeholders theory as a useful approach to manage the problem of overtourism in historical cities—illustrated with an example of Krakow. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2019, 5, 685–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Tourism Organization (UNWTO); Centre of Expertise Leisure, Tourism & Hospitality; NHTV Breda University of Applied Sciences; NHL Stenden University of Applied Sciences. ‘Overtourism’?—Understanding and Managing Urban Tourism Growth beyond Perceptions, Executive Summary; Madrid, Spain, 2018. Available online: https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/book/10.18111/9789284420070 (accessed on 2 March 2022).

- Goodwin, H. The Challenge of Overtourism. Responsible Tour. Partnership. 2017. Available online: https://www.millennium-destinations.com/uploads/4/1/9/7/41979675/rtpwp4overtourism012017.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Brookes, N. Mankind and Mega-projects. Front. Eng. Manag. 2014, 1, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leick, A.; Hesse, M.; Becker, T. From the “project within the project” to the “city within the city”? Governance and Management Problems in Large Urban Development Projects Using the Example of the Science City Belval, Luxembourg. Spat. Res. Plan. 2020, 78, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Gellert, P.; Lynch, B. Mega-projects as displacements. Int. Soc. Sci. J. 2003, 55, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruzelius, N.; Flyvbjerg, B.; Rothengatter, W. Big decisions, big risks. Improving accountability in mega projects. Transp. Policy 2002, 9, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz Orueta, F. Madrid: Urban regeneration projects and social mobilization. Cities 2007, 24, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flyvbjerg, B. The Oxford Handbook of Megaproject Management; Flyvbjerg, B., Ed.; CPI Group: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Flyvbjerg, B.; Bruzelius, N.; Rothengatter, W. Megaprojects and Risk: An Anatomy of Ambition; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Del Cerro Santamaría, G. Urban Megaprojects: A Worldwide View; Emerald: Bingley, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Flyvbjerg, B. Machiavellian megaprojects. Antipode 2005, 37, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Habitat. Sustainable Development Goals. Monitoring Human Settlements Indicators. 2015. Available online: https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/2020/06/sustainable_development_goals_summary_version.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- BBSR—Federal Institute for Research on Building. The New Leipzig Charter. The Transformative Power of Cities for the Common Good. 2021. Available online: https://www.bmi.bund.de/SharedDocs/downloads/EN/eu-presidency/gemeinsame-erklaerungen/new-leipzig-charta-2020.pdf;jsessionid=ADE8FB60A490BDA3AEAA0F3672A82E6F.1_cid364?__blob=publicationFile&v=7 (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- Gobierno de España. Urbana, M.d.T.M.y.A. AUE—Agenda Urbana Española 2019, Plan de Acción. 2019. Available online: https://www.aue.gob.es/recursos_aue/06_plan_de_accion_age.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- Ajam, M. Leading Megaprojects. A Tailored Approach; Auerbach Publications: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Drouin, N.; Sankaran, S.; Marrewijk, A.; Müller, R. 18. Conclusions and reflections: What have we learnt about megaproject leaders? In Megaproject Leaders. Reflections on Personal Life Stories; Drouin, N., Sankaran, S., Marrewijk, A., Müller, R., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2021; pp. 288–297. [Google Scholar]

- Di Maddaloni, F.; Davis, K. Project manager’s perception of the local communities’ stakeholder in megaprojects. An empirical investigation in the UK. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2017, 36, 542–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Delphine; Witte, P.; Spit, T. Megaprojects–An anatomy of perception: Local people’s perceptions of megaprojects: The case of Suramadu, Indonesia. disP-Plan. Rev. 2019, 55, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzoise, V.; Slanzi, D.; Poli, I. Local stakeholders’ narratives about large-scale urban development: The Zhejiang Hangzhou Future Sci-Tech City. Urban Stud. 2020, 57, 655–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Porras, L.; Heikkinen, A.; Kujala, J. Understanding stakeholder influence: Lessons from a controversial megaproject. Int. J. Resour. Dev. Manag. 2021, 21, 191–213. [Google Scholar]

- Eskerod, P.; Huemann, M.; Savage, G. Project Stakeholder Management—Past and Present. Proj. Manag. J. 2015, 46, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, M. Public Participation in Planning: An intellectual history. Aust. Geogr. 2005, 36, 283–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarazona Vento, A. Mega-project meltdown: Post-politics, neoliberal urban regeneration and Valencia’s fiscal crisis. Urban Stud. 2017, 54, 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibert, O. Megaprojekte und Partizipation. Konflikte zwischen handlungsorientierter und diskursiver Rationalität in der Stadtentwicklungsplanung. disP-Plan. Rev. 2007, 171, 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shatkin, G. Planning Privatopolis: Representation and Contestation in the Development of Urban Integrated Mega-Projects. In Worlding Cities: Asian Experiments and the Art of Being Global; Roy, A., Ong, A., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2011; pp. 77–97. [Google Scholar]

- Zeković, S.; Maričić, T.; Vujošević, M. Megaprojects as an instrument of urban planning and development: Example of Belgrade Waterfront. In Technologies for Development: From Innovation to Social Impact; Hostettler, S., Najih Besson, S., Bolay, J.-C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 153–164. [Google Scholar]

- Soja, E. The city and spatial justice. In Proceedings of the Spatial Justice, Nanterre, Paris, France, 12–14 March 2009; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Marcuse, P. Spatial justice: Derivative but Causal of Social Justice. In Justice et Injustices Spatiales; Bret, B., Gervais-Lambony, P., Hancock, C., Landy, F., Eds.; Presses Universitaires de Paris Nanterre: Nanterre, France, 2010; pp. 76–92. [Google Scholar]

- Swyngedouw, E.; Moulaert, F.; Rodriguez, A. Neoliberal Urbanization in Europe: Large-Scale Urban Development Projects and the New Urban Policy. Antipode 2002, 34, 542–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferber, U.; Grimski, D.; Millar, K.; Nathanail, P. Sustainable Brownfield Regeneration; University of Nottingham: Nottingham, 2006; Available online: https://issuu.com/guspin/docs/nameaa6734 (accessed on 20 November 2020).

- Ortiz, A. The Qualitative Interview. In Research in the College Context, 2nd ed.; Stage, F., Manning, K., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; pp. 57–71. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, C. Interviewing. In Qualitative Research in Health Care; Holloway, I., Ed.; McGraw-Hill: Maidenhead, UK, 2005; pp. 39–54. [Google Scholar]

- Kallio, H.; Pietilä, A.-M.; Johnson, M.; Kangasniemi, M. Systematic methodological review: Developing a framework for a qualitative semi-structured interview guide. J. Adv. Nurs. 2016, 72, 2954–2965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández Sempieri, R.; Fernández Collado, C.; Baptista Lucio, M.d.P. Metodología de la Investigación, 5th ed.; Mc Graw Hill: Mexico City, Mexico, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Dierckx de Casterle, B.; Gastmans, C.; Bryon, E.; Denier, Y. QUAGOL: A guide for qualitative data analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2012, 49, 360–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kuckartz, U. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse. Methoden, Praxis, Computerunterstützung, 4th ed.; Beltz Juventa: Weinheim, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mayring, P. Qualitative Content Analysis. Theoretical Foundation, Basic Procedures and Software Solution; Beltz: Klagenfurt, Slovenia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Queirós, A.; Faria, D.; Almeida, F. Strengths and Limitations of Qualitative and Quantitative Research Methods. Eur. J. Educ. Stud. 2017, 3, 369–387. [Google Scholar]

- Alsaawi, A. A Critical Review of Qualitative Interviews. Eur. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2014, 3, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Peräkylä, A. Validity in Qualitative Research. In Qualitative Research, 3rd ed.; Silverman, D., Ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011; pp. 413–427. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, D. Introducing Qualitative Research. In Qualitative Research, 3rd ed.; Silverman, D., Ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011; pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Genz, C.; Tschoepe, A.Y. Ethnographie als Methodologie. Zur Erforschung von Räumen und Raumpraktiken. In Handbuch Qualitative und Visuelle Methoden der Raumforschung; Heinrich, A.J., Marguin, S., Million, A., Stollmann, J., Eds.; Transcript: Bielefeld, Germany, 2021; pp. 225–236. [Google Scholar]

- Crouch, M.; McKenzie, H. The logic of small samples in interview-based qualitative research. Soc. Sci. Inf. 2006, 45, 483–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rädiker, S.; Kuckartz, U. Focused Analysis of Qualitative Interviews with MAXQDA. Step by Step; MAXQDA Press: Berlin, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- El País. El Fondo IPIC de Abu Dabi Compra el 100% de Cepsa. El País. 2011. Available online: https://elpais.com/economia/2011/02/16/actualidad/1297845181_850215.html (accessed on 14 January 2022).

- Mubadala; The Carlyle Group. Media Release; 14.01.2022. 2019. Available online: https://www.cepsa.com/stfls/corporativo/FICHEROS/NOTAS_DE_PRENSA/Mubadala-Carlyle-Press-Release.pdf (accessed on 14 January 2022).

- El País. 26M Elecciones Municipales, Santa Cruz de Tenerife. El País. 2019. Available online: https://resultados.elpais.com/elecciones/2019/municipales/05/38/38.html (accessed on 5 January 2022).

- Reverón, E. El edil de Urbanismo de Santa Cruz insta al Gobierno de Canarias a desmantelar El Tanque. El Día 2021. Available online: https://www.eldia.es/santa-cruz-de-tenerife/2021/10/18/edil-urbanismo-santa-cruz-insta-58476282.html (accessed on 5 January 2021).

- Arencibia de Torres, J. Refinería de Tenerife, 1930—2005: 75 Años de Historia; CEPSA: Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz Rodríguez, M.d.C.; García Herrera, L.M.; Armas Díaz, A. Puertos y espacios públicos renovados: El puerto de Santa Cruz de Tenerife. In Proceedings of the XVIII Coloquio de Historia Canario-Americana, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain, 13–17 October 2008; pp. 914–922. [Google Scholar]

- INE—Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Hogares por Régimen de Tenencia de la Vivienda y Comunidades Autónomas. Available online: https://www.ine.es/dyngs/INEbase/es/categoria.htm?c=Estadistica_P&cid=1254735570688 (accessed on 7 May 2020).

- Torres, N. El PSOE sigue adelante con la denuncia del Santa Cruz Verde 2030. Diario de Avisos 2018. Available online: https://diariodeavisos.elespanol.com/2018/12/el-psoe-sigue-adelante-con-la-denuncia-del-santa-cruz-verde-2030/ (accessed on 7 December 2020).

- Gobierno de Canarias. Plan de Calidad del Aire de la Aglomeración Santa Cruz de Tenerife—San Cristobal de la Laguna, por Dióxido de Azufre. Available online: http://www.gobiernodecanarias.org/cptss/sostenibilidad/temas/planificacion-ambiental/planes_calidad_aire/ (accessed on 18 November 2019).

- Reverón, E. El Gobierno de Canarias Anuncia que Cepsa Desmantelará la Refinería en 2022. El Día. 2021. Available online: https://www.eldia.es/santa-cruz-de-tenerife/2021/05/12/gobierno-anuncia-cepsa-desmantelara-refineria-51704906.html (accessed on 7 February 2022).

- Armas Díaz, A. Reestructuración urbana y producción de imagen: Los espacios públicos en Santa Cruz de Tenerife. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de la Laguna, Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Strauch, L.; Takano, G.; Hordijk, M. Mixed-use spaces and mixed social responses: Popular resistance to a megaproject in Central Lima, Peru. Habitat Int. 2015, 45, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, C.; Sim, V.; Scott, D. Contested discourses of a mixed-use megaproject: Cornubia, Durban. Habitat Int. 2015, 45, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Jurado, E.; Romero-Padilla, Y.; Romero-Martínez, J.M.; Serrano-Muñoz, E.; Habegger, S.; Mora-Esteban, R. Growth machines and social movements in mature tourist destinations Costa del Sol-Málaga. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1786–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, D.M.W.; Tang, B.S. Social order, leisure, or tourist attraction? The changing planning missions for waterfront space in Hong Kong. Habitat Int. 2015, 47, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, W. ‘From the Frying Pan to the Oven’: Gentrification and the Experience of Industrial Displacement in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. Urban Stud. 2007, 44, 1427–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Herrera, L.M.; Sabaté Bel, F. Global Geopolitics and Local Geoeconomics in Northwest Africa: The Industrial Port of Granadilla (Canary Islands, Spain). Geopolitics 2009, 14, 589–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, V. Lofts in translation: Gentrification in the Warehouse District, Regina, Saskatchewan. Can. Geogr. /Le Géographe Can. 2019, 63, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giloth, R.; Betancur, J. Where Downtown Meets Neighborhood: Industrial Displacement in Chicago, 1978–1987. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 1988, 54, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuk, M.; Bierbaum, A.; Chapple, K.; Gorska, K.; Loukaitou-Sideris, A. Gentrification, Displacement, and the Role of Public Investment. J. Plan. Lit. 2018, 33, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcuse, P. Gentrification, Abandonment, and Displacement: Connections, Causes, and Policy Responses in New York City. Wash. Univ. J. Urban Contemp. Law 1985, 28, 195–240. [Google Scholar]

- Majoor, S. The Disconnected Innovation of New Urbanity in Zuidas Amsterdam, Ørestad Copenhagen and Forum Barcelona. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2009, 17, 1379–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziomba, M. Städtebauliche Grossprojekte der Urbanen Renaissance. Projektziele im Spannungsfeld zwischen öffentlicher Steuerung und Immobilienmarktmechanismen. disP-Plan. Rev. 2007, 43, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, R. Emerging Urbanity: Global Urban Projects in the Asia Pacific Rim; Spon Press: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hanakata, N.; Gasco, A. The Grand Projet politics of an urban age: Urban megaprojects in Asia and Europe. Palgrave Commun. 2018, 4, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bornstein, L. Mega-projects, city-building and community benefits. City Cult. Soc. 2010, 1, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleibert, J.M.; Kippers, L. Living the good life? The rise of urban mixed-use enclaves in Metro Manila. Urban Geogr. 2016, 37, 373–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Organization/Institution | Function | Date | Place |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I1 | Professional Association of Real Estate Experts (APEI) | Regional delegate | 23.08.2019 | Office, Santa Cruz |

| I2 | Urban Planning office, town hall Santa Cruz | Chief officer (Ciudadanos, C’s) | 30.08.2019 | Office, Santa Cruz |

| I3 | Real estate agent | Self-employed | 02.09.2019 | Office, Santa Cruz |

| I4 | Local association of industrial monument preservation | President | 04.09.2019 | Public café, Santa Cruz |

| I5 | Local environmental association (Ecologistas en Acción) | Representative | 12.09.2019 | Public café, San Cristóbal de la Laguna |

| I6 | Conservative Party (Partido Popular, PP) | Member of city parliament, former chief officer in the urban planning office | 09.03.2020 | Public café, Santa Cruz |

| I7 | Architect | Self-employed, former president of the Chamber of Architect of the Canary Islands | 12.03.2020 | Office, Santa Cruz |

| I8 | University of La Laguna, Department of Geography | Geographer, research associate | 03.09.2020 | Office, San Cristóbal de la Laguna |

| I9 | Local journalist | Self-employed, former head of a local newspaper | 03.09.2020 | Public café, Santa Cruz |

| I10 | Chamber of Architects of the Canary Islands | Three employees/members | 07.09.2020 | Public café, Santa Cruz |

| I11 | Labor Party (Partido Socialista Obrero Español; PSOE) | Member of the city parliament, former chief officer in the urban planning office | 09.09.2020 | Online |

| I12 | Buenos Aires Neighborhood | Neighbor | 10.09.2020 | Public café, Santa Cruz |

| I13 | Local government of Santa Cruz | Mayor | 11.09.2020 | Town hall, Santa Cruz |

| I14 | Local neighborhood association (preservation of history) | President and vice president | 11.09.2020 | Online |

| I15 | Left-wing Party (Unidas Podemos) | Member of the city parliament | 11.09.2020 | Town hall, Santa Cruz |

| I16 | Local neighborhood association of homeowners | President | 11.09.2020 | Public café, Santa Cruz |

| I17 | Institute for History of Art, University of La Laguna | Art historian, research associate | 17.09.2020 | Online |

| I18 | CEPSA (oil refinery) | Representative | 26.01.2021 | Written document |

| Main Topics | Subtopics |

|---|---|

| Refinery and the city | Public/political protest against the industrial activity Importance of the refinery for the city Demolition of the refinery Relation between refinery and adjacent quarters |

| Santa Cruz Verde 2030 | Opinion of the proposed uses and functions General perception of the megaproject Public discussion Possible positive and negative effects |

| Possible positive and negative effects | Positive and negative impacts Housing market Quality of life Current status and future of adjacent neighborhoods (Buenos Aires, Chamberí, Cabo-Llanos) |

| Planning | Planning Validity Participation Examples/references in the world Transparency |

| Cabo-Llanos | First phase of deindustrialization/reasons Conflicts in the neighborhoods Learning process/lessons learnt Monument preservation/el Tanque |

| Politics | Change of government Role of the two different governments Political dimension of the project Instrument for the election campaign |

| European Union | |

|---|---|

| |

| Spanish Government | |

| |

| Government of the Canary Islands | |

| |

| Government of Tenerife | |

| |

| Local Port Authority | |

| |

| Monument Preservation Association | |

|---|---|

| |

| Chamber of Architects of Tenerife, La Gomera and El Hierro | |

| |

| The Media | |

| |

| Real Estate Experts | |

| |

| Neighbors and Neighborhood Organizations | |

|---|---|

| |

| Local Environmental Association | |

| |

| Free Architects/Other Experts | |

| |

| Local University | |

| |

| Unidas Podemos (Left-Wing Party) | |

| |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hübscher, M. Planning behind Closed Doors: Unlocking Large-Scale Urban Development Projects Using the Stakeholder Approach on Tenerife, Spain. Land 2022, 11, 390. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11030390

Hübscher M. Planning behind Closed Doors: Unlocking Large-Scale Urban Development Projects Using the Stakeholder Approach on Tenerife, Spain. Land. 2022; 11(3):390. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11030390

Chicago/Turabian StyleHübscher, Marcus. 2022. "Planning behind Closed Doors: Unlocking Large-Scale Urban Development Projects Using the Stakeholder Approach on Tenerife, Spain" Land 11, no. 3: 390. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11030390

APA StyleHübscher, M. (2022). Planning behind Closed Doors: Unlocking Large-Scale Urban Development Projects Using the Stakeholder Approach on Tenerife, Spain. Land, 11(3), 390. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11030390