1. Introduction

This paper aims at exploring the implementation of sustainability issues in the Historic Preservation field. The focus of such research on techniques and procedures of heritage preservation delves into the multiple roles of cultural heritage in fostering and empowering sustainable development processes, imagining cultural heritage to become a laboratory for (urban) innovation and creativity. In this sense, conservation is no longer explored within the traditional disciplinary borders, but it investigates the ways of contributing to the economy and society.

The case study to be discussed is the ongoing restoration of the Romanesque church of St. James (S. Giacomo) in Como [

1]. The church itself is currently underused and mostly closed to the public. However, thanks to a legacy left by a generous lady, it will be restored to complete and enhance the new museum of Como Cathedral.

Given these premises, this paper will analyze the strategies that could link the restoration of this kind of cultural heritage and the foundation of a new museum with urban development and regeneration strategies in a context that encompasses tourism as a primary economic sector in the region.

Associated scientific questions as such are therefore manifold.

The importance of cultural tourism and cultural economy for cities has been ever-growing in recent decades, pointing out expressly the role of museums [

2,

3,

4]. Furthermore, since 2011, the concept of Historic Urban Landscape (HUL) was introduced; the topic has been more often explored for sites inscribed in the UNESCO World Heritage List [

5,

6], but several studies investigated middle-size cases, which could be understood as more similar to the Como case, where networking seems to be a key factor for success [

7].

The conflictual relationships between preservation and tourism management have been intensely investigated, as many authors underscored the risks of overtourism and its negative effects, exploring the topic of carrying capacity [

8,

9]. Other studies tend to see the related social conflicts as less dramatic, showing data from surveys involving more or less directly affected persons in the related processes [

10,

11]. Besides the concerns related to the social conflicts and the economic effects on the sustainability of the local economy, the main concerns about overtourism focus on the changes affecting the urban structure, meaning the changes of the functions and the population, and therefore, the impact on historical buildings and the broader neighborhood context, including environmental effects [

12]. The growing importance of the tourism sector in urban economies often produces effects similar to what has been called gentrification [

13]; in this sense, the Como case study is quite interesting for further diachronic examinations.

Recent studies illustrate experiences of urban regeneration based on the awareness of such complex issues [

14]; in that direction, it is essential to take into account also the potentialities introduced by the digitization of cultural institutions as a tool to empower the cooperation opportunities between urban material structure and the nonmaterial cultural and economic background [

15].

In this perspective, the implementation of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in the cultural heritage sector, not only in developing countries [

16] but also for an urban agenda to be implemented in Europe [

17], became crucial, in line with the target to empower an approach respectful of complexity. The point here is to demystify those unidimensional proposals promising to get the individual target yet seem unable to be conscious of the side effects and risks of undesired feedback in the long run.

It seems clear at first glance that many mistakes can occur if simple recipes are implemented without a more comprehensive analysis of relationships, collateral impacts, negative and positive externalities, potential spillovers, and feedback. Environmental transition opened a series of conflicts, for instance, on the effects of the insertion of devices for renewable energy in sensitive landscapes. Such conflicts cannot be simply discussed in terms of abstract priorities; they require a deeper investigation of what heritage values could work for the future, in a perspective of strong sustainability [

18], dealing with a better transition and not against the transition.

Thus, this paper aims to debate significant open questions about the implementation of sustainability criteria as an instrumental mode of enhancing policies in the heritage field, with a particular focus on the territorial and/or urban development programs led by policies related to heritage assets.

2. Methodology

The research, carried out around the St. James’ conservation project and Como Cathedral Museums, investigated the urban context for its long process of urban policies, also presented as a best practice in the literature.

The literature analysis and the collection of relevant data on demographic trends provided the elements to highlight the outcomes of those policies and the current opportunities/threats for the local development model. In that regard, culture and rules for the redevelopment of the inner city played an essential synergistic role.

The literature analysis involved the multiple fields that are relevant for the investigation in the practice of the problem of theoretical and practical links between urban strategies:

Architectural, archaeological, and symbolic importance of the involved historical buildings;

The cultural environment, which produced the currently being condition of the historic center of Como, referring both to planning issues and the issue of authenticity as a nodal point in the discussion on the interventions carried out in the last fifty years, which shaped the current image of Como historic center;

The economic structure of the region and its trends;

The tourism industry in Como and the Lake Como region also refers to the impact of tourism on the real estate market.

The picture emerging from the discussed analysis introducing the models and concepts seems helpful for the purpose. The most important points are the implementation of what happened in Como Walled City and the options currently under debate of the concepts of gentrification, commodification, and sustainability, the latter being also discussed in the perspective of the UN 2030 Agenda.

The conclusions have, therefore, a double direction: on the one hand, some recommendations seem to emerge, which could be helpful to guide the program of the restoration and the design of the new museum; on the other hand, some general remarks appear on the urban regeneration strategies for historic cities whose economy is growing as related to the tourism market.

3. Results

St. James’ church is in the middle of the Walled City of Como, next to the Cathedral. Its long history produced an extremely rich and layered monument, whose significance can be found both in the original structure and its further developments.

To date, scholarly research debates agree that the church was founded by Bishop Rainaldus, a significant historical figure due to his diplomatic work between the Pope and the German Empire; the church’s architectural features are meaningfully close to the characters of the so-called Hirsauer Bauschule [

19,

20]. Moreover, as founded by the Bishop in a position next to the Cathedral and the Bishop Palace, St. James was undoubtedly part of the Cathedral complex; actually, the space between the two churches became the symbolic and practical center of the political life of the medieval town, as proposed by recent studies [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26] (p. 134) (

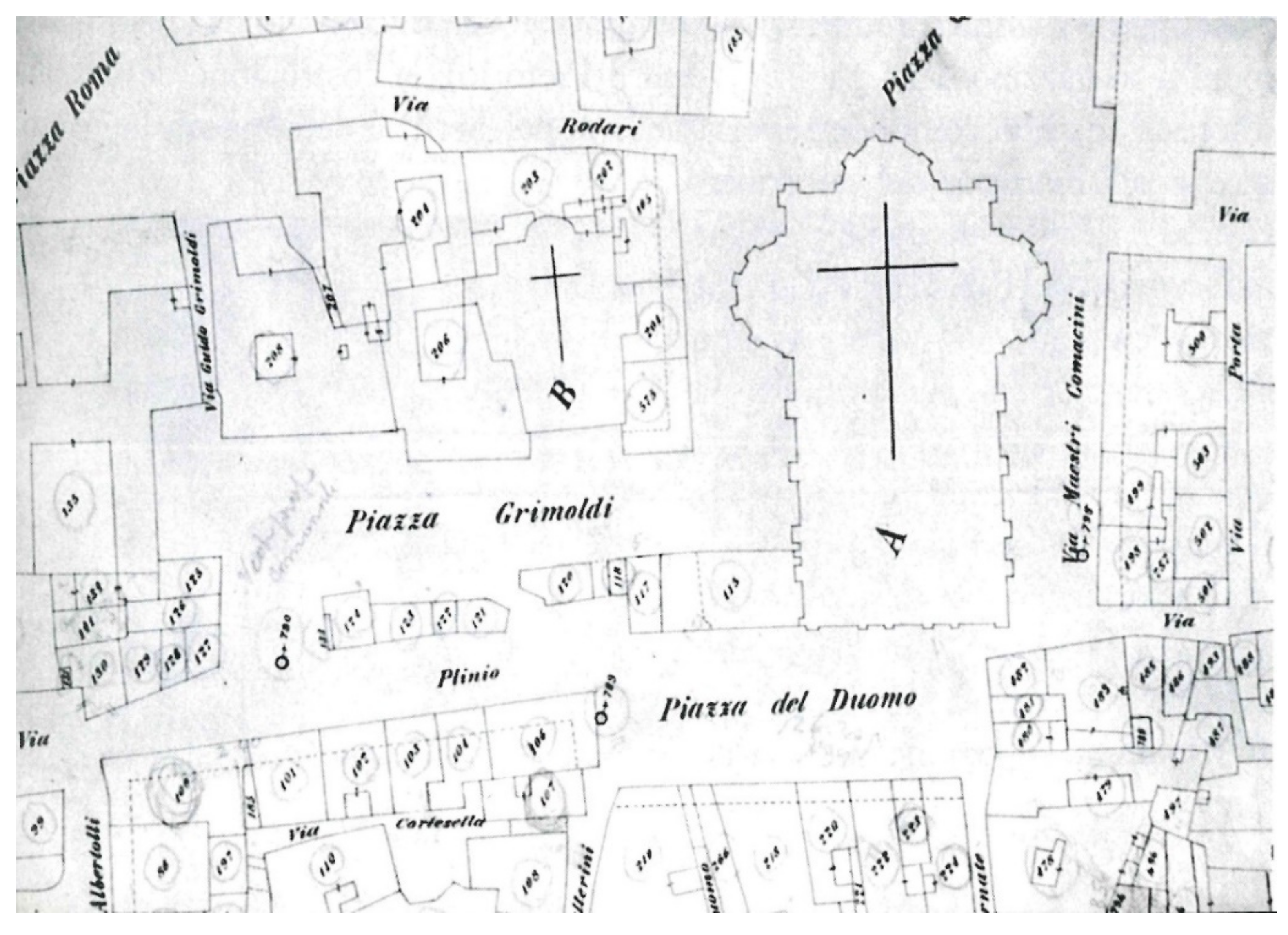

Figure 1).

Transformed in several different phases, the church was “discovered” by scholars already in the 1800s [

27] and went through a pretty hard restoration in 1970, which put into light several elements of the medieval construction. Unfortunately, some layers have been removed during that intervention without a methodology capable of keeping at least the material evidence’s readability (

Figure 2).

As introduced above, the case study of St. James church in Como is located in the inner core of the town, that is the historic center of Como, which keeps the orthogonal grid given by the Romans, the medieval walls, and also mostly medieval buildings aligned on the narrow streets. The Walled City is an interesting case because of the planning policies promoted at the end of the Sixties by the mayor Antonio Spallino [

28], contemporary to the better-known experiences carried out in other Italian cities such as Bologna [

29,

30]. It is worth mentioning that the intervention in St. James’ was consistent with the approach implemented in the same years in the frame of such policies for the historic center.

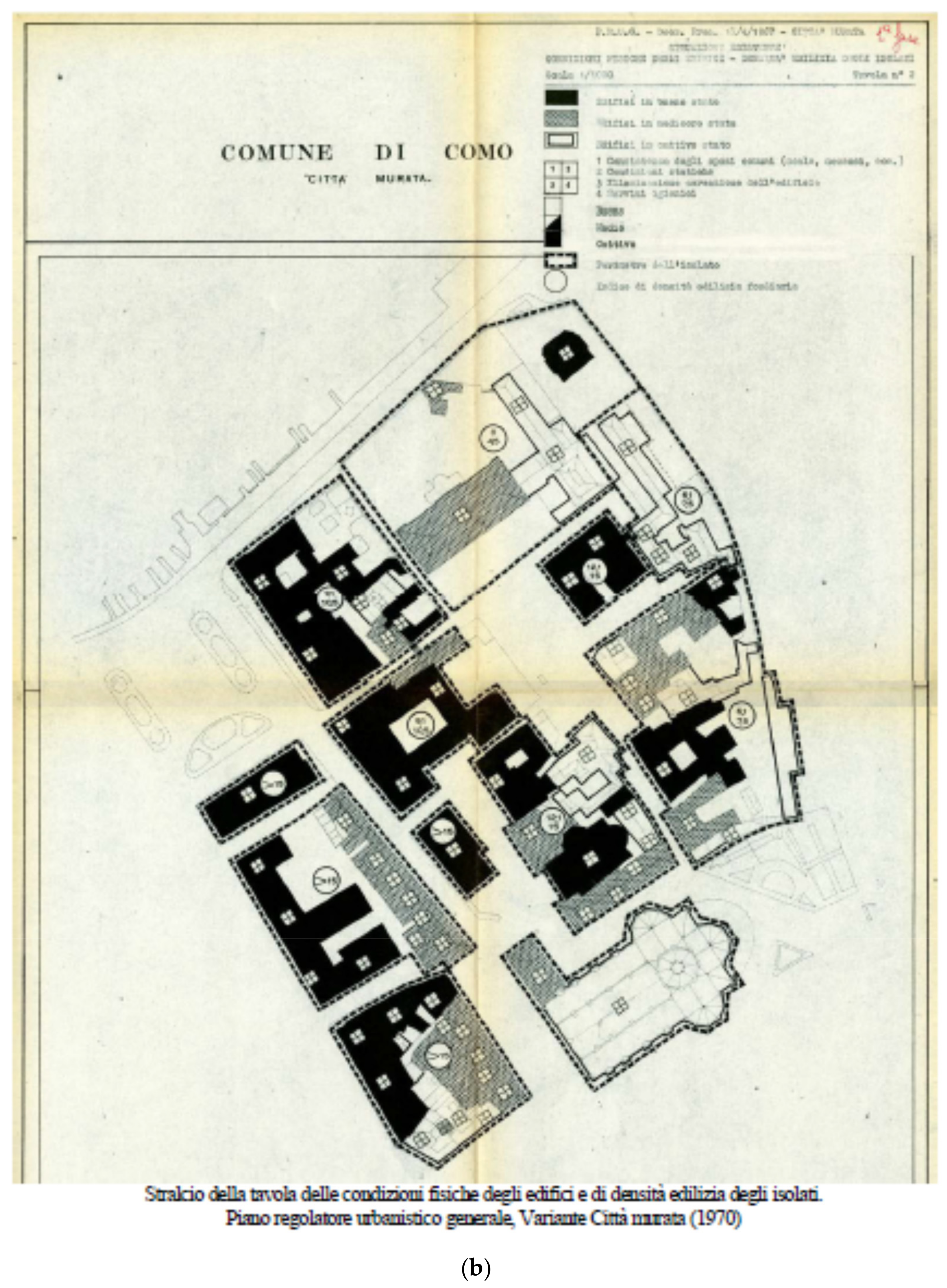

In the preparatory studies for the special urban plan of the Walled City (

piano particolareggiato), while conventional urban planning specialists were involved for the first time, planning methodologies were implemented based on the theory of typology as developed by Gianfranco Caniggia in line with Muratori’s theory [

31]. Then, this plan was exported to other contexts, including the Walled City of Nicosia, Cyprus [

32]. Como’s case is then often considered in urban morphology studies [

33,

34,

35,

36]. It is worthy of underscoring that in Como, the attention paid to the historic fabric of the buildings in the central district turned into strict regulations and development processes, which started with the firm will to not exclude social housing from the central district. However, maybe this process ended up in something different (

Figure 3a,b).

As for most ancient, fortified cities, the inner part of the urban structure of Como has consistently been recognized as a distinguished part that is also manifested in the collection of statistical data. It is worthy to notice that in 1881, the population of the Walled City was one-third of the whole population of the municipality, while after World War II, in 1951, even if the percentage was lowered to one-sixth, the number of residents was more or less the same. (

Table 1).

That means that the planning policies focused on the development of new fringes have also been boosted by the rationalist movement heralded in Como by the famous architect Giuseppe Terragni. Not to be overlooked, in the inner part of the town, the rationalist architects came to well-known clashes with the historic urban structure [

37], presented as a form of urban blight, when depreciation and decline of the attractiveness of the central quarters were ongoing. In other words, the social composition and role of the population of the inner quarters were changing. In that situation, the politics presented the destruction of the urban center as a case of “

risanamento”, a word coined for the extensive intervention on Naples in 1885, meaning “redevelopment”, but regarding health. The mainstream rhetoric about the need to destroy the old neighborhoods for public health reasons was then well expressed for Como by a young filmmaker, in a celebrative movie, in which the first sequences describe the removal of the central neighborhood named

Cortesella as performed with a surgical knife [

38] (

Figure 4).

Later, between 1951 and 1968, the Walled City tended toward abandonment; the number of residents decreased from 11,047 to 8184 (−26%), while in the same years, the population of the whole municipality increased by 32%, from 70,447 to 91,792. The trend has been the same for the Walled City and the whole town. However, the loss of population has been dramatic in the twenty years after the enforcement by the municipality promoted the plan (

Table 1).

The physical conservation of the historic fabric could not stop the obsolescence of the urban structure, including buildings, but above all, narrow streets are hardly usable by cars in front of new lifestyles. Therefore, one of the most questioned issues was the restricted use of streets open to pedestrians and bicycles, not to cars and motorcycles, unless for residents requiring parking and for commercial deliveries only in some hours of the day. As enforced by the municipality, these restrictions had faced strong opposition from the owners, shopkeepers, and residents. Maybe there was a partial improvement in the real estate values, but in the long run, the real effect was to make the site more attractive for shops, and less for housing.

Nowadays, prices in the central district of the town are very high. As a result, most ground floors have been turned into shops, but many upper floors are not used, and their market value risks are being reduced because of the difficult accessibility. Nevertheless, the market logic seems to have chosen to exploit the best opportunities and a “wait and see” strategy for cases that look more difficult to be requalified; the average real estate prices are very high in the lake region and the downtown neighborhoods as well.

In recent years, as a new trend, many apartments have been requalified and put on the market not for dwelling, but as non-hotel accommodation facilities. The space available in the historic center is not enough for investments in new hotels. However, the conversion of empty apartments into small and privately managed non-hotel facilities is much easier. Data collecting on this process is not very accessible, but the statistical offices estimate that in five years after 2014, the number of non-hotel facilities grew by more than 20%.

The process of converting spaces into tourism accommodation was supported by the impressive trend of Como as a tourist destination; according to the Operative Unit “Studi e Statistica” of the Como-Lecco Chamber of Commerce, focusing just on the years before the COVID-19 pandemic, in 2014, Como had 465,625 “presenze” (nights spent) and in 2018 779,985, with the percentage of foreigners growing from 77.1 to 81.4. Furthermore, the number of visitors for one-day trips was much higher, as visiting and shopping in Como downtown was always a “must” for tourists staying in hosting facilities (hotels and other types of accommodations) in the lake region.

Therefore, even during the last ten years, despite the construction sector crisis, especially during the pandemic since 2020, the described trend went on, supporting the market prices of buildings in the Walled City (and, of course, on the lakeshore). As a result, the number of residents is growing slowly, but renovation works on historic buildings grow, supported by the tourism market. Nevertheless, the works still tend to follow the cultural lines set up fifty years ago, extending the pedestrian zones and controlling the quality of private works, even on legally nonprotected historic buildings.

The dramatic reduction of residents in the Walled City of Como between 1970 and 1990 corresponded with the substitution of homes and crafts with banks and often luxurious shops; the aesthetic quality of restored buildings was more and more appreciated and became a factor for higher real estate prices, especially for shops. Despite the discourse on the enforced policies, which should have protected the poor living conditions in the old central quarters and conserved a social mix in the Walled City, spatial segregation happened in the progress of time. In the last years, the immigrants’ neighborhoods settled not in the center but the fringes of the town.

Undoubtedly, the process can be inscribed in the category named by Ruth Glass in 1964 “gentrification”, with the pros and cons of a category whose interpretation has been evolving in the last decades.

4. Discussion

4.1. The Outcomes of 1970 Como Walled City Plan: Gentrification, Commodification, Authenticity

The depopulation process in Como Walled City could be described as an instance of what since 1964 has been known as gentrification: the movement of middle and upper-class residents into the former working-class districts of cities. Such a topic has been widely debated worldwide for its processes affecting the cities’ nature and destiny and its impact on the real estate market and the social composition of local communities.

In that regard, there are a variety of valid interpretations of the gentrification concept. For instance, some authors focused on the “unfortunate desecration of interesting and ‘authentic’ urban neighborhoods, a dilution of vibrant ethnic neighborhoods into something bland and uninteresting. At worst, the critics of gentrification have viewed the phenomenon as a major source of disadvantage for low-income urban residents who, having established a community with all of its complex social networks, must now see it torn apart as they are displaced—either by choice or compulsion—to move to other housing that is less desirable” [

13] (p. 2). However, on the other hand, other authors have viewed it as a beneficial undoing of abandonment due to the obsolescence of old districts in front of changing lifestyles, seeing the refurbishment and requalification of the abandoned buildings as a positive process. In other words, it is two-fold: what has been called “gentrification” may be unfortunate for the former residents, either forced to displace or decided to leave by themselves, can also be understood as a natural part of urban development, connected to the aging of durable housing stock.

The perspectives are different, as they look alternatively to the whole story or just to the consequential phases. The question is whether conditions such as abandonment, aging, and obsolescence are “natural”, or they are the outcome of political decisions, which favor “creative class” with the hope of turning the historic districts into new and fashionable urban scenarios. Nevertheless, once the former “authentic” neighborhood has been gentrified, a new urban regeneration strategy must be carefully set up, as the new urban perspective will be different, facing the reality of the place.

The case of Como, in particular, must be understood, paying attention also to the driving forces of the local economy, which in the same years experienced a dramatic change, so that Como is now in search of an identity, and this opens a different perspective and moves the emphasis towards a different understanding of this “gentrification” process and its outcomes.

At the time of the special plan for the Walled City, Como was an important industrial district for the textiles industry, internationally well known for the production of precious silk fabrics for the world of high fashion [

39]. However, after a rapid decline related to globalization processes [

40,

41], nowadays, Como and its lake is mainly a classy tourist destination with a strong international appeal, sometimes reinforced by the label of a creative city, as industrial activities are not entirely over, and some of the silk brands are still active, also opening to digital transition [

42].

Therefore, Como is at a crossroads: on one side, there is the perspective to find a place among creative cities; on the other side, there is the perspective to exploit the brand of the lake and the related cultural resources. In the latter case, the risk is no longer gentrification, which may be considered a process already carried out, but with commodification. Here is where “authenticity” comes to the discussion because of the risks of commodification related to tourism.

Nowadays, authenticity is understood as highly desired by tourists, where they “search for authenticity of experiences” [

43] (p. 589) and where “tourism promotes local awareness” [

44] (p. 10). However, some misunderstandings about the authenticity concept can turn into management practices while putting heritage on stage and over-restoring buildings and sites to enhance attractiveness by something that looks merely authentic, but it is not. The risk is to compromise a more complex understanding, which implies slower times, maybe not compatible with mass tourism. The sustainability of a tourism-oriented approach should then be inquired, not to refuse the economic benefits of tourism for local systems but to understand which policies may make these benefits more durable and safer from negative side effects.

The special plan for the Walled City was enforced in the Seventies with the support of a particular sector of the municipality technical offices and with the support of a kind of cultural tendency, which made fashionable among local architects the attention paid to the typological and constructive character of the buildings in the historic center. Gianfranco Caniggia’s method, therefore, was adopted not only for the approach to understanding the urban structure but also to guide restoration projects. The basis of the method was the respect for a particular form of authenticity, reflected in the typological process more than in the material fabric; despite ideas on conservation developed by contemporary scholars, Caniggia and his followers practiced a systematic scraping off all the layers of plasters, substitutions, and local reconstructions. In a few years, these interventions went through severe criticism by most Italian academics, oriented towards an idea of authenticity more focused on material authenticity [

45,

46]. As articulated above, the restoration of St. James’s church belongs to this local stream.

Even if the methodologies implemented by Caniggia and followers may be under question today, in reflections on the theory of architectural conservation, complaints can concern the loss of the more decadent layers, not the creation of a fake environment. In the backstage of Caniggia’s method, genuine and honest research produced further debate and a deeper understanding. The scholarly research outcomes on Como and its arts and architecture history show that the items are considerable and increased in number year by year. Additionally, it is noteworthy that all the periods and styles have been investigated. Such studies have been produced not just on the favorite medieval architecture with its stone-façade features but also those Renaissance and Baroque phases, which were witnessed by the painted plasters that have often been the victims of Caniggia’s scrapes, starting from the restoration of Casa Bazzi in via Olginati (1968–69), which was the manifesto of Caniggia’s method (

Figure 5).

In other words, ingenuous research has been the cure against the risk of losing authenticity, and this seems to be an important lesson learned for future strategies. For the discourse we are developing here, the point is relevant not under the perspective of conservation theories but because of the relevance of authenticity in the discussion about gentrification and commodification. Fifty years later, the effects of the new attention driven on the Walled City, no longer as a blight to be removed but as an asset to be valorized with sensitive policies, can also be evaluated in their links with the categories of gentrification and commodification.

4.2. Management Integration and SDGs

As we know, the Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, adopted by United Nations General Assembly in 2015, is a global action plan for “people”, “planet” and “prosperity”, which pursues the improvement of “peace” in more considerable freedom and “partnership” universally. At the same time, underscoring the 17 SDGs, the UN Agenda argues that there is a need to focus on the 5Ps (people, planet, prosperity, peace, partnership) to measure the SDGs progress effectively [

47]. Thus, the essential point is to understand the link between cultural heritage and sustainable development/SDGs. In other words, how culture and cultural heritage can contribute to 5Ps [

48] in a more holistic perspective while underlying the interrelated nature of SDGs and in what manner their role can empower the “humanistic and ecological paradigm of a sustainable city” [

17] are as much significant.

With the implementation of sustainable development through such an action plan, the UN Agenda went beyond the general idea of sustainable development as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” [

49] (p. 43). With that perspective, the Agenda is structured along four dimensions of a holistic approach: “inclusive social development”, “inclusive economic development”, “environmental sustainability” and “peace and security” [

50]. However, despite great scholarly efforts, heritage and cultural policies, conventions, and programs highlighting the relationship between heritage and sustainable development, culture and heritage are not comprehensively integrated into the 17 SDGs and their targets. Such recognition is explicitly expressed in Target 11.4 to “protect and safeguard the world’s cultural and natural heritage” in a broader urban strategy with the purpose to “make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable” (SDG11, so-called “Urban SDG”). In this sense, there are systematic synergies among the UN SDG11 and the 2016 New Urban Agenda (Habitat III) process in a way that the effective “integration of culture and cultural heritage into urban development plans and policies” [

17] (p. 2). Such recognition can improve essential services, facilities, infrastructures, transportation, and local people’s quality of life through land regeneration and urban rehabilitation, creating jobs by reusing historical buildings, etc.

In the case of Como, the area certainly requires integrated policies to exploit its assets in a sustainable way, keeping off the risks of overtourism and including culture and tourism in a new development model. The fact itself that Como Walled City hosts nowadays less than the 40% of the residents living there one century ago implies that an effective development model and a set of smart regulations on the reuse of existing buildings can still exploit a wide potential of underused buildings for urban redevelopment and regeneration. Yet, the main critical point is to understand SDGs as a matrix of implementations in a holistic perspective, moving beyond the most obvious outputs, to reach the nexus between preservation, urban systems, values, and development policies. In this sense, the investment in this (privately funded) operation on St. James’s church could be decisive if it turns into a proof of concept of the potential of heritage as a factor for the implementation of SDGs in a European country.

In the ongoing St. James’s operation, the most advanced digital techniques are implemented [

51], such as the 3D survey carried out by a team from Politecnico di Milano under the responsibility of Marco Scaioni (

Figure 6); the traditional stone slabs covering the roofs will be treated, extending their service life, instead of disposing and replacing them with new stones transported from a far distance quarries with a high carbon footprint [

52]; and a more efficient heating system will reduce the energy consumption, as already tested in other important churches in Italy [

53], which is an issue to be dealt with also taking into account the Climate Change impacts [

54]. However, as advanced and noninvasive as they are, those methodological choices will not fully reach their targets without comprehensive reflections on the potential role of such an important monument in the urban system and the set of targets that could be hit, enhancing the integration of the cultural offers, the training institutes, the return on the investment in conservation, the cooperation among the players in the local economy. In other words, to improve the effectiveness of the essential and critical ongoing experiments/operations and valorize the Walled City of Como, it is vital to introduce/design and promote a new reading for their network of resources to initiate a new economy for the Como interventions empowering the local development [

55].

Taking advantage of being in Lombardy Region, where advanced models of wide-area comprehensive programs for heritage-led local development have been successfully tested since 2000 [

56,

57] (pp. 195–197), the business plan for the new Cathedral Museum could be the opportunity to develop an alliance on the urban basis for sustainable management of the important and until today, under-valorized cultural assets of the town. In that sense, the vision of a sustainable management system gave us the key to the intervention of the St. James’s and Cathedral Museum that is going to be planned not simply as the business plan of museum thought as a firm, strictly focusing on its value-chain, but working on the relationships and externalities, which the opportune models can represent and evaluate [

4].

The most apparent network is the one that connects the new Cathedral Museum with the Pinacoteca in the Volpi palace, where artworks from the Middle Ages to the Modern period are exhibited [

58]. Many relationships can be highlighted among the collections in the Pinacoteca and the new museum; many arts historical concepts may be understood only by visiting both the collections, which explain each other. Furthermore, integrated ticketing, promotion, and cultural, educational, and research activities may be easily organized through collaboration and cooperation with public and private educational institutes and cultural and creative industries.

The need for such a network is due to organizational problems and to enhance the number of visitors. As said above, the number of tourists in Como is very high, and most of them do not miss visiting the Cathedral. However, the number of visitors of the Pinacoteca is definitely unsatisfactory: according to the data provided by Como Municipality, an average of 10,000 visitors in the years pre-COVID, among which more than half were for free. Therefore, if the Pinacoteca is taken as a benchmark for the Cathedral Museum, the first lesson to be learned is that the attractiveness of these art collections should be enhanced by promotion, and new ticketing strategies should be introduced to reach a number of visitors corresponding to an acceptable percentage of the managing costs.

However, even more interesting are the opportunities related to some special characters of the Cathedral collections, which encompasses important Renaissance tapestries and a rare and outstanding textile object recently discovered in the Cathedral [

59]. The textiles sector is extremely important in Como, where a Silk Museum has been working already for some years, building the basis for a cultural policy that contributes to the vision of Como networking with creative cities [

60].

Therefore, a network among the different local museums could be useful both to seek a better performance of all the different museums standing alone and nonreaching a critical mass, as well as structure connections and cooperation among the cultural actors, widening the constellation of stakeholders involved in a policy that could keep the town far from the risks of commodification. The issue of networking has been developed on the basis of several on field experiences in the peculiar Italian context; the network capability of such local museums should be promoted by raising awareness of the potential and limits of such local assets in the tourism market, and their scale should also be rationally appropriated “to the efficient margin of different services”, in order to ensure not only the survival of its network but also promote their development toward active contribution to sustainable tourism [

7]. Networking is now officially recommended in the frame of the Italian National Museums System started up in 2018.

5. Conclusions

To sum up, developing a new business plan for the new Cathedral Museum, which will work on the vision of urban complex networks of Como resources to create an alliance among them, is fundamental as much. Such a plan should have an impact on the level of urban strategies, calling all the stakeholders at different levels, to share decisions on the integration of cultural offer, cultural institutes, the variety and spatial distribution of hotels and other facilities, the coordination of opening times, the road and public transportation infrastructures, and, above all, the engagement in the different activities. Among those stakeholders, it would be strategic to include the educational sector and the industries acting in environmental and digital transition, which could turn cultural heritage into a laboratory for engaging and connecting people, implementing a business model capable of producing more and more positive externalities.

We envision all those issues to be evaluated in terms of opportunities, practical to control the ongoing trends, for preventing commodification and the other unsustainable effects, which are now impacting not only Como Walled City but also most historic cores of European towns. That is the vision of a correctly understood conservation program that can improve the implementation of several SDGs through their interrelated nature. Last but not least, the comprehensive consideration of such opportunities enables us to show a much more complex system of relationships among preservation activities and urban/spatial mechanisms. To effectively work, such a new “relational model” [

61] should contemplate “active cultural participation” of diverse actors and their “collective actions, collective learning through cooperation” [

61], hopefully enabling them to be actively and collectively involved in cultural/cultural heritage activities, the problems solving and the co-creation processes [

55]. In that sense, leveraging culture and cultural heritage in such a “participatory inclusiveness framework” becomes crucial for implementing SDGs effectively.