Tourism Industry Attitudes towards National Parks and Wilderness: A Case Study from the Icelandic Central Highlands

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Management and Governance of Protected Areas

3. National Parks and the Tourism Industry

4. Study Area

4.1. Iceland and its National Parks

4.2. The Central Highlands of Iceland

4.3. Regional Planning in the Central Highlands

5. Methods

5.1. Methodological Approach

5.2. Online Survey

5.3. Semi-Structured Interviews

6. Results

6.1. The Attraction of the Central Highlands

[The Central Highlands], that’s the reason Iceland is so special. It’s because we have this untouched wilderness and this gem, the Highlands where you see no man-made structures. You can walk and hike for days, and there is only you and black sand, and you know, glacier rivers. And it’s rare and we should protect it.

6.2. Attitudes towards the Central Highlands National Park

A national park has the advantage of raising a set of questions regarding what the suitable development for the entire area is, and that should be a public debate. It is also an opportunity to reflect on all the land uses that are in the area and try to address them in a more comprehensive using a more holistic approach. As of today, the Highlands is just sliced between municipalities who if they want to benefit from their backcountry, they will either want to have their own dam, their own accommodation or tourist attraction or fishing area or whatever. That they can retrieve some sort of financial income out of it. I think this kind of current situation is calling for everyone to look within their own area which part should be developed and which part should be preserved and as such that is kind of leading to a more developer approach of the Highlands, where you have this project of building up the roads, the development of accommodations, footbridges and this kind of things. Whenever you start to group municipalities together and try to look at the more regional plan, there are more interesting approaches that start to emerge.

It’s a big area and it’s very difficult to protect it so we need strong regulations. We need to have tools to respond when people are driving off road or even when private ownership is doing something with land that will break up the scenery for very big area, you know. We need tools to do something about it. So, it [the CHNP] is a very good idea. Of course, all regulation needs to be implemented carefully and it needs to consider all sides. But it’s necessary in my opinion, yes.

We have taken care of our nature and try to bring it to the next generation as the best we can. Now, the situation in Iceland is that 80 percent of the people that live in Iceland are living in the south west corner […] Now suddenly these people that are living there […] they do not trust me anymore to take care of my land […] My grandfather he took care of this land here. I am born in this land here and I die in this land. […] These park things are taking it from the people who have taken care of it all their lives, all the generations. Generation, after generation, after generation. Now it’s not good enough what we have done and some agency in Reykjavík or whatever should tell me what is best.

Let’s say a bridge needs to be built because the river changes its path or someone needs to build a cabin or fix something, to fix a trail, to create a new trail, just to react to the everchanging nature. I’m scared that if all the power is away from the locals and in Reykjavik and the locals can’t change where the bridge is or change something, that it would be just like a mammoth that can’t move, like a big, big ship and you can’t turn it because it’s so big.

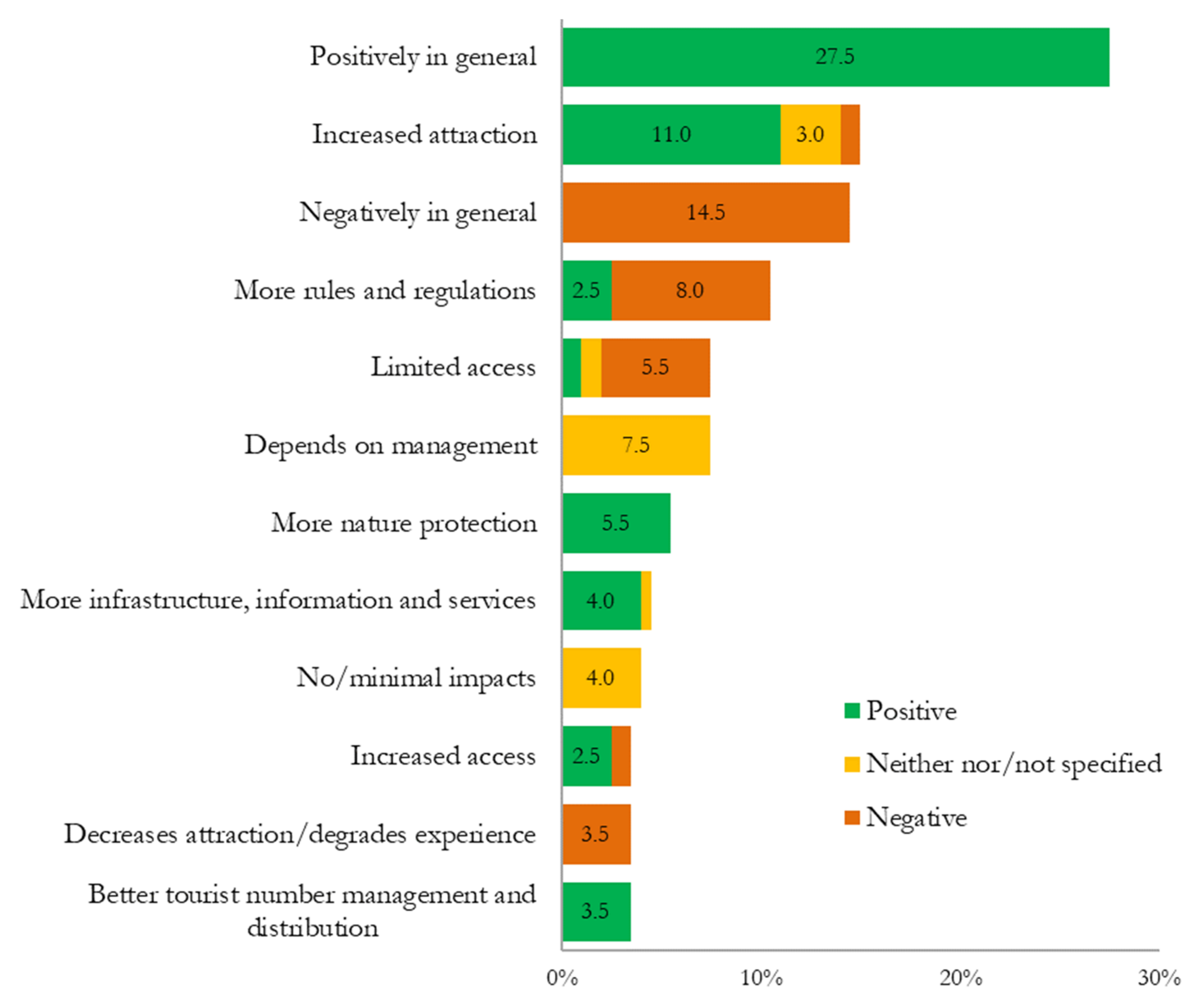

6.3. Perceived Impacts of the Establishment of the Central Highlands National Park

6.4. Preferences for the Governance of Central Highlands National Park

7. Discussion and Conclusions

7.1. Conflicting Views among Tourism Service Providers Regarding National Parks

7.2. Governance of National Parks and Wilderness Areas

7.3. Coexistence between Nature-Based Tourism and Nature Conservation

Like most other industries, tourism stresses natural environments through a range of infrastructure development, resource consumption and waste generation processes. In contrast to many other industries, these processes occur in some of the most ecologically fragile locations on the planet. In addition, tourism is often the only industry in locations where other kinds of operations and industries would never be permitted

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Worboys, G.; Lockwood, M.; Kothari, A.; Feary, S.; Pulsford, I. Protected Area Governance and Management; ANU Press: Canberra, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Newsome, D.; Moore, S.A.; Dowling, R.K. Natural Area Tourism: Ecology, Impacts, and Management; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Saarinen, J. Wilderness use, conservation and tourism: What do we protect and for and from whom? Tour. Geogr. 2016, 18, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M.; Frost, W. (Eds.) Introduction: The making of the national park concept. In Tourism and National Parks: International Perspectives on Development, Histories and Change; Routledge: London, UK, 2009; pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.M. Wasteland to World Heritage: Preserving Australia’s Wilderness; Melbourne University Press: Carlton, Australia, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Fredman, P.; Sandell, K. ‘Protect, preserve, present’—The role of tourism in Swedish national parks. In Tourism and National Parks: International Perspectives on Development, Histories and Change; Frost, W., Hall, C.M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2009; pp. 197–208. [Google Scholar]

- Butzmann, E.; Job, H. Developing a typology of sustainable protected area tourism products. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 1736–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slocum, S.L. Operationalising both sustainability and neo-liberalism in protected areas: Implications from the USA’s National Park Service’s evolving experiences and challenges. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 1848–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, S.W.; Butler, R.W. Tourism and the Canadian national park system: Protection, use and balance. In Tourism and National Parks: International Perspectives on Development, Histories and Change; Frost, W., Hall, C.M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2009; pp. 102–113. [Google Scholar]

- Nash, R.F. Wilderness and the America Mind; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wall-Reinius, S.; Fredman, P. Protected areas as attractions. Ann. Tour. Res. 2007, 34, 839–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiper, N. Tourism Systems: An Interdisciplinary Perspective; Massey University: Palmerston North, NZ, USA, 1990; 289p. [Google Scholar]

- Weiler, S.; Seidl, A. What’s in a name? Extracting econometric drivers to assess the impact of national park designation. J. Reg. Sci. 2004, 44, 245–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haukeland, J.V. Tourism stakeholders’ perceptions of national park management in Norway. J. Sustain. Tour. 2011, 19, 133–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esfandiar, K.; Dowling, R.; Pearce, J.; Goh, E. Personal norms and the adoption of pro-environmental binning behaviour in national parks: An integrated structural model approach. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 10–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhakka, R.; Saarinen, J. New Role of Tourism in National Park Planning in Finland. J. Environ. Dev. 2013, 22, 411–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Iceland. Selected Items of the Exports of Goods and Services 2013–2021. 2021. Available online: https://px.hagstofa.is/pxen/pxweb/en/Efnahagur/Efnahagur__utanrikisverslun__3_voruthjonusta__voruthjonusta/UTA05003.px (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Óladóttir, O.Þ. Erlendir ferðamenn á Íslandi 2021: Lýðfræði, ferðahegðun og viðhorf [International Tourists in Iceland 2021: Demographic, Travel Behaviour and Attitudes]; Icelandic Tourist Board: Reykjavík, Iceland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Dudley, N. Guidelines for Applying Protected Area Management Categories; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Nyaupane, G.P.; Poudel, S.; York, A. Governance of protected areas: An institutional analysis of conservation, community livelihood, and tourism outcomes. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 30, 2686–2705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, K.S.; Clark, D.A.; Slocombe, D.S. Introduction: Protected areas in a changing world. In Transforming Parks and Protected Areas: Policy and Governance in a Changing World; Routledge: London, UK, 2008; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- UNDP. Governance for Sustainable Human Development—A UNDP Policy Document; UNDP: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Borrini-Feyerabend, G.; Hill, R. Governance for the conservation of nature. In Protected area governance and management; Worboys, G.L., Lockwood, M., Kothari, A., Feary, S., Pulsford, I., Eds.; ANU Press: Canberra, Australia, 2015; pp. 169–206. [Google Scholar]

- Eagles, P.F.J. Governance of recreation and tourism partnerships in parks and protected areas. J. Sustain. Tour. 2009, 17, 231–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaltenborn, B.P.; Qvenild, M.; Nellemann, C. Local governance of national parks: The perception of tourism operators in Dovre-Sunndalsfjella National Park, Norway. Nor. Geogr. Tidsskr. Nor. J. Geogr. 2011, 65, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagles, P.F.J.; Romagosa, F.; Buteau-Duitschaever, W.C.; Havitz, M.; Glover, T.D.; McCutcheon, B. Good governance in protected areas: An evaluation of stakeholders’ perceptions in British Columbia and Ontario Provincial Parks. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 60–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagles, P.F.J. Governance models for parks, recreation, and tourism. In Transforming Parks and Protected Areas: Policy and Governance in a Changing World; Hanna, K.S., Clark, D.A., Slocombe, D.S., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2008; pp. 39–61. [Google Scholar]

- Allendorf, T.D. A global summary of local residents’ attitudes toward protected areas. Hum. Ecol. 2020, 48, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, M.J. The power of trust: Toward a theory of local opposition to neighboring protected areas. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2008, 21, 859–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredman, P.; Friberg, L.H.; Emmelin, L. Increased Visitation from National Park Designation. Curr. Issues Tour. 2007, 10, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, M.; Müller, M.; Woltering, M.; Arnegger, J.; Job, H. The economic impact of tourism in six German national parks. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2010, 97, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siltanen, J. Economic Impact of Iceland’s Protected Areas and Nature-Based Tourism Sites. Report for the Ministry for the Environment and Natural Resources; Hagfræðistofnun Háskóla Íslands: Reykjavík, Iceland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Iceland. Population—Key Figures 1703-2021. 2021. Available online: https://px.hagstofa.is/pxen/pxweb/en/Ibuar/Ibuar__mannfjoldi__1_yfirlit__yfirlit_mannfjolda/MAN00000.px (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Icelandic Tourist Board. Numbers of Foreign Visitors. Available online: https://www.ferdamalastofa.is/en/recearch-and-statistics/numbers-of-foreign-visitors (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Icelandic Tourist Board. Fyrstu spár um meginstærðir ferðaþjónustu [First Predications on Main Tourism Indicators]; Icelandic Tourist Board: Reykjavík, Iceland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Karl Benediktsson; Guðríður Þorvarðardóttir. Frozen opportunities? Local communities and the establishment of Vatnajökull National Park, Iceland. In Mountains of Northern Europe: Conservation, Management, People and Nature; Thompson, D.B.A., Price, M.F., Galbraith, C.A., Eds.; TSO Scotland: Edinburgh, Scotland, 2005; pp. 335–348. [Google Scholar]

- Ólafsdóttir, R.; Runnström, M.C. How wild is Iceland? Assessing wilderness quality with respect to nature based tourism. Tour. Geogr. 2011, 13, 280–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waage, E.R.H. Vatnajökulsþjóðgarður: Spegilmynd samfélagslegra gilda [Vatnajökull National Park: The Reflection of Societal Values]; Raunvísindadeild Háskóla Íslands: Reykjavík, Iceland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lög um Vatnajökulsþjóðgarð, nr. 60/2007. Available online: https://www.althingi.is/lagas/nuna/2007060.html (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Samráðsgátt. Drög að frumvarpi til laga um Hálendisþjóðgarð [Draft of a Bill for a Central Highlands National Park]. Available online: https://samradsgatt.island.is/oll-mal/$Cases/Details/?id=2575 (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Bishop, M.V. Public Views on the Central Highland National Park: Conditions for a Consensus among Recreational Users; University of Iceland: Reykjavík, Iceland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Social Science Research Institute. Þjóðmálakönnun—Unnið fyrir faghóp um samfélagsleg áhrif virkjana [National Survey—For the Expert Group on Social Impacts of Power Plants]; Social Science Research Institute: Tokyo, Japan, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Capacent Gallup. Náttúruverndarsamtök Íslands—Viðhorf til þjóðgarðs á miðhálendi Íslands [The Icelandic Nature Conservation Association—Attitudes towards a Central Highlands National Park]; Capacent Gallup: Reykjavik, Iceland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Capacent Gallup. Fleiri andvígir en fylgjandi frumvarpi um hálendisþjóðgarð [More Opposed Than in Favour of the Bill on the Central Highlands National Park]; Capacent Gallup: Reykjavik, Iceland, 18 January 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Capacent Gallup. Landvernd og Náttúruverndarsamtök Íslands—Hálendisverkefni [The Icelandic Environment Association and the Icelandic Nature Conservation Association—Central Highlands Project]; Capacent Gallup: Reykjavik, Iceland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Alþingi. Þingsályktun um landsskipulagsstefnu 2015-2026. Þskj. 1027-101. mál. (Parliamentary Resolution on National Planning Strategy. Number 1027-101 case). Available online: http://www.althingi.is/altext/145/s/1027.html (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Ministry for the Environment; The National Planning Agency. Miðhálendi Íslands, Svæðisskipulag 2015 [The Central Highlands, Regional Plan 2015]; Ministry for the Environment & The National Planning Agency: Reykjavík, Iceland, 1999.

- Veal, A.J. Research Methods for Leisure and Tourism: A Practical Guide; Pearson Education: Harlow, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hung, K.; Law, R. An overview of internet-based surveys in hospitality and tourism journals. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 717–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods, 5th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A. Basics of Qualitative Research—Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Frost, W.; Hall, C.M. (Eds.) Tourism and National Parks: International Perspectives on Development, Histories and Change; Routledge: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Holden, A. Environment and Tourism; Routledge: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.M. Tourism Planning: Policies, Processes and Relationships; Pearson Prentice Hall: Harlow, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ólafsdóttir, R.; Sæþórsdóttir, A.D.; Runnström, M. Purism scale approach for wilderness mapping in Iceland. In Mapping Wilderness. Concepts, Techniques and Applications; Carver, S., Fritz, S., Eds.; Springer: London, UK, 2016; pp. 157–176. [Google Scholar]

- Ólafsdóttir, R.; Haraldsson, H. Tourism spatial dynamics and causal relations: A need for holistic understanding. In A Research Agenda for Tourism Geographies; Müller, D., Ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2019; pp. 128–137. [Google Scholar]

- Haraldsson, H.V.; Ólafsdóttir, R. Evolution of tourism in natural destinations and dynamic sustainable thresholds over time. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, R. Interactive elephants: Nature, tourism and neoliberalism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 44, 88–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCannell, D. The Tourist: A New Theory of the Leisure Class; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Büscher, B. Transforming the Frontier: Peace Parks and the Politics of Neoliberal Conservation in Southern Africa; Duke University Press: Durham, UK; London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sæþórsdóttir, A.D. Preserving Wilderness at an Emerging Tourist Destination. J. Manag. Sustain. 2014, 4, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sæþórsdóttir, A.D. Ferðamennska á miðhálendi Íslands: Staða og spá um framtíðarhorfur [Tourism in the Central Highlands: Current Status and Future Prospects]; Institute of Life and Environmental Sciences: Reykjavik, Iceland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sæþórsdóttir, A.D.; Ólafsdóttir, R. Planning the wild: In times of tourist invasion. J. Tour. Res. Hosp. 2017, 6, 1000163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sæþórsdóttir, A.D.; Hall, C.M. Visitor satisfaction in wilderness in times of overtourism: A longitudinal study. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 123–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sæþórsdóttir, A.D. Managing popularity: Changes in tourist attitudes to a wilderness destination. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2013, 7, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.; Ólafsdóttir, R. Nature-based tourism as therapeutic landscape in a COVID era: Autoethnographic learnings from a visitor’s experience in Iceland. GeoJournal 2022, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, A. Turning ideas on their head: The new paradigm for protected areas. Georg. Wright Forum 2003, 20, 8–32. [Google Scholar]

- Dearden, P.; Bennet, M.; Johnston, J. Trends in protected area governance, 1992–2002. Environ. Manag. 2005, 36, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkhata, B.A.; McCool, S.F. Coupling Protected Area Governance and Management ghrough Planning. J. Enviromental Policy Plan. 2012, 14, 394–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nastran, M. Why does nobody ask us? Impacts on local perception of a protected area in designation, Slovenia. Land Use Policy 2015, 46, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliku, O.; Schraml, U. Making sense of protected area conflicts and management approaches: A review of causes, contexts and conflict management strategies. Biol. Conserv. 2018, 222, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, J.; Amos, B.; Plumptre, T.W. Governance Principles for Protected Areas in the 21st Century; Institute on Governance: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.M.; Page, S.J. The Geography of Tourism and Recreation: Environment, Place and Space, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- McDonagh, J.; Ólafsdóttir, R.; Weir, L.; Mahon, M.; Farrell, M.; Welling, J.T.; Conway, T. ‘There’s no transfer of knowledge, it’s all one way’: The importance of integrating local knowledge and fostering knowledge sharing practices in natural resource utalisation. In Sharing Knowledge for Land Use Management: Decision-Making and Expertise in Europe’s Northern Periphery; McDonagh, J., Tuulentie, S., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2020; pp. 116–129. [Google Scholar]

- Ólafsdóttir, R. The role of public participation for determining sustainability indicators for Arctic tourism. Sustainability 2021, 13, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, D. Justice, Nature and the Geography of Difference; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Relph, E. Place and Placelessness; Pion: London, UK, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Saarinen, J. Wilderness, tourism development, and sustainability: Wilderness attitudes and place ethics. In Personal, Societal, and Ecological Values of Wilderness: Sixth World Wilderness Congress Proceedings on Research, Management, and Allocation, Volume I, Bangalore, India, 1998; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station: Ogden, UT, USA, 1998; pp. 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, P.; Ponsford, I. Confronting tourism’s environmental paradox: Transitioning for sustainable tourism. Futures 2009, 41, 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutter, P.S. Driven Wild. How the Fight against Automobiles Launched the Modern Wilderness Movement; University of Washington Press: Seattle, WA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

| Number | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| N | % | |

| Type of business | ||

| Daytour operators | 181 | 65 |

| Travel agencies | 127 | 46 |

| Other | 26 | 9 |

| Location of company’s headquarters | ||

| Capital area | 135 | 51 |

| North Iceland | 47 | 18 |

| South Iceland | 42 | 16 |

| West Iceland | 13 | 5 |

| Westfjords | 10 | 4 |

| Reykjanes | 9 | 3 |

| East Iceland | 7 | 3 |

| Length of company’s operation in years | ||

| Less than 5 years | 69 | 26 |

| 5 to 9 years | 71 | 26 |

| 10 to 14 years | 51 | 19 |

| 15 to 24 years | 42 | 16 |

| 25 years or longer | 37 | 14 |

| Number of full time employees in August 2019 | ||

| None | 39 | 15 |

| 1 | 97 | 36 |

| 2 to 3 | 70 | 26 |

| 4 to 9 | 28 | 11 |

| 10 to 19 | 10 | 4 |

| 20 or more | 22 | 8 |

| Areas used by the participating company’s | ||

| South Iceland | 278 | 74 |

| Central Highlands | 221 | 59 |

| West Iceland | 207 | 55 |

| North Iceland | 198 | 53 |

| Capital area | 197 | 52 |

| Reykjanes | 186 | 49 |

| East Iceland | 154 | 41 |

| Westfjords | 125 | 33 |

| N | Avg. | SD | t-Test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Do not use the Central Highlands | 88 | 3.18 | 1.459 | t = 2.865 |

| Use the Central Highlands | 157 | 2.69 | 1.523 | p = 0.004 |

| N | Avg. | SD | t-test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| National parks attract tourists | Do not use the Central Highlands | 112 | 3.97 | 1.127 | t = 3.041 |

| Use the Central Highlands | 177 | 3.53 | 1.353 | p = 0.003 | |

| Public investment in national parks is positive for the tourism industry | Do not use the Central Highlands | 108 | 3.79 | 1.136 | t = 2.029 |

| Use the Central Highlands | 176 | 3.49 | 1.305 | p = 0.043 | |

| Public investment in national parks is positive for nature | Do not use the Central Highlands | 108 | 3.66 | 1.224 | t = 0.917 |

| Use the Central Highlands | 176 | 3.52 | 1.269 | p = 0.360 | |

| National parks have positive effects on local communities | Do not use the Central Highlands | 111 | 3.62 | 1.258 | t = 1.632 |

| Use the Central Highlands | 172 | 3.37 | 1.302 | p = 0.104 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sæþórsdóttir, A.D.; Wendt, M.; Ólafsdóttir, R. Tourism Industry Attitudes towards National Parks and Wilderness: A Case Study from the Icelandic Central Highlands. Land 2022, 11, 2066. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11112066

Sæþórsdóttir AD, Wendt M, Ólafsdóttir R. Tourism Industry Attitudes towards National Parks and Wilderness: A Case Study from the Icelandic Central Highlands. Land. 2022; 11(11):2066. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11112066

Chicago/Turabian StyleSæþórsdóttir, Anna Dóra, Margrét Wendt, and Rannveig Ólafsdóttir. 2022. "Tourism Industry Attitudes towards National Parks and Wilderness: A Case Study from the Icelandic Central Highlands" Land 11, no. 11: 2066. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11112066

APA StyleSæþórsdóttir, A. D., Wendt, M., & Ólafsdóttir, R. (2022). Tourism Industry Attitudes towards National Parks and Wilderness: A Case Study from the Icelandic Central Highlands. Land, 11(11), 2066. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11112066