Spatial Evolution and Driving Mechanism of City Networks in the Middle and Lower Ganges Valley from the 16th to the Mid-18th Century

Abstract

:1. Introduction

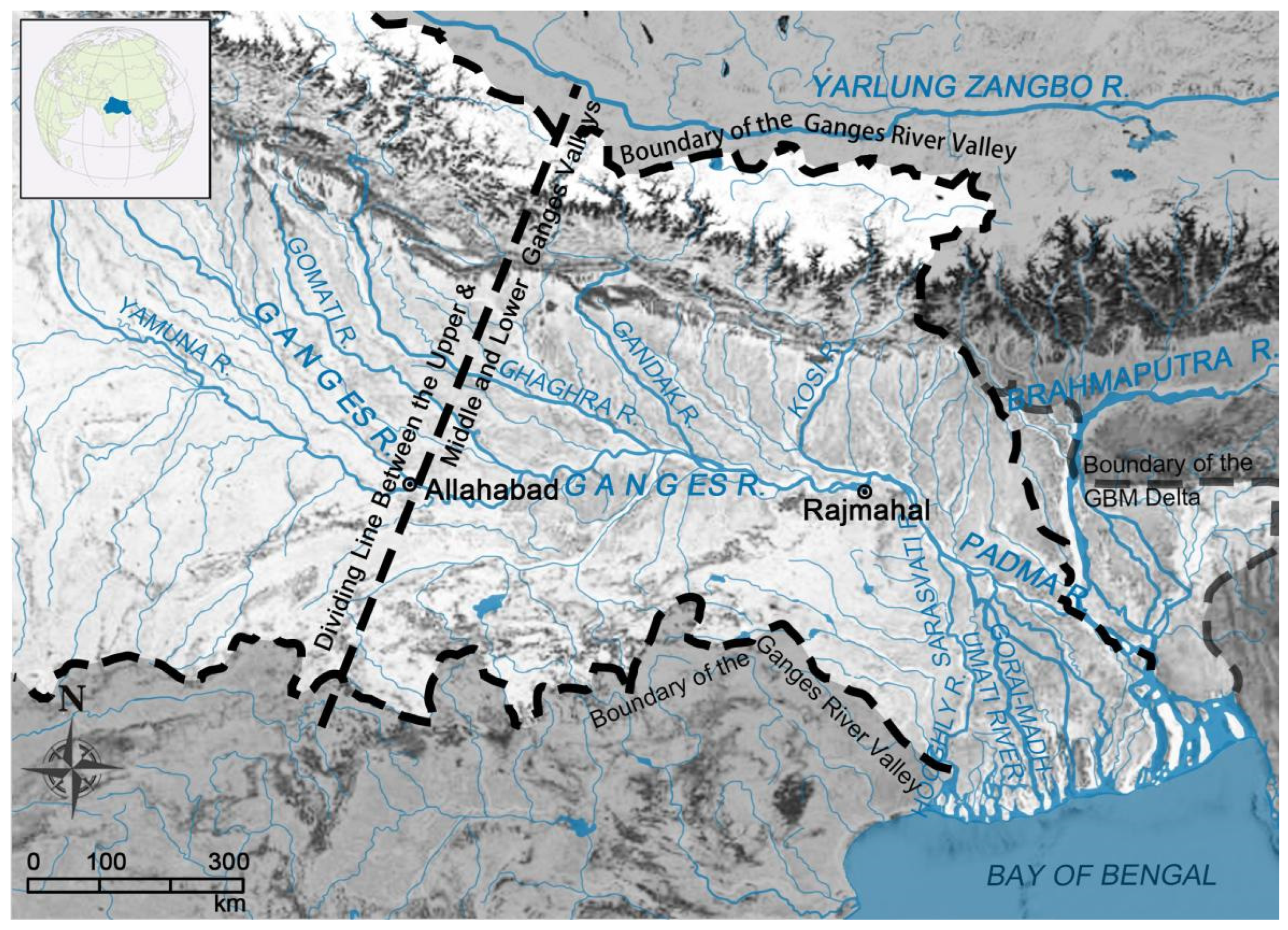

2. Historical Background and Basic Factors Influencing City Networks

2.1. Geographical Environment

2.2. Political System

2.3. Industry and Commerce

2.4. Ideology and Culture

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Analytical Methods

3.2. Materials and Technical Methods

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Analysis of the Forces and Mechanism Driving the Evolution of City Networks

4.1.1. Analysis of Centripetal Forces

4.1.2. Analysis of Centrifugal Forces

4.2. Analysis of Spatial Pattern Formed by the Evolution of City Networks

4.2.1. Polycentric Axis Network: Overall Pattern of City Networks in the Middle and Lower Ganges Valley

4.2.2. Diverse Secondary Networks: Subregional Patterns of City Networks in the Middle and Lower Ganges Valley

4.3. The Functional Structure of the City Network

4.4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Name of Province and Sarkar | Area (Square Miles) | Tax Unit Jama (Dams) * | Tax Per Square Mile |

|---|---|---|---|

| BENGAL | 71,160 | 254,370,562 | 3574.62847 |

| Tanda/Udambar (Rajmahal, Murshidabad and North Birbhum) | 3511 | 24,078,700.5 | 6858.07477 |

| Guar/Lukhnauti (mainly Malda) | 1772 | 18,846,976 | 10,635.991 |

| Fatehabad (Faridpur, South Bakarganj) | 3063 | 7,969,568 | 2601.88312 |

| Mahmudabad (North Nadia, North Jessore and West Faridpur) | 5110 | 11,610,256 | 2272.06575 |

| Khalifatabad (South Jessore and West Bakarganj) | 5157 | 5,402,140 | 1047.53539 |

| Bakla (North and West Bakarganj and South-west Dhaka) | 2020 | 7,131,641 | 3530.51535 |

| Purnea | 2182 | 6,408,793 | 2937.1187 |

| Tajpur (West Dinajpur) | 2209 | 6,483,857 | 2935.20009 |

| Ghoraghat (South Rangpur, South-East Dinajpur and North Bogra) | 3761 | 8,983,072.5 | 2388.47979 |

| Panjra/Pinjarah (Dinajpur, part of Rangpur and Rajshahi) | 1861 | 5,803,275 | 3118.36378 |

| Barbakabad (mainly Rajshahi, South-west Bogra and South-east Malda) | 2878 | 17,451,532 | 6063.77067 |

| Bazuha (Partly Rajshahi, Bogra, Pabna and Dhaka) | 8548 | 39,516,871 | 4622.93765 |

| Sonargaon (West Tripura and Noakhali) | 3975 | 10,331,333 | 2599.07748 |

| Silhat/Sylhet (Srihatta) | 5488 | 6,681,308 | 1217.4395 |

| Chatgaon/Chittagong | 2483 | 11,424,310 | 4601.01087 |

| Sharifabad (Mostly Burdwan) | 2105 | 22,488,750 | 10,683.4917 |

| Sulaimanabad (North Hooghli, part of Nadia and East Burdwan) | 2388 | 17,629,964 | 7382.73199 |

| Satgaon/Saptgram (24 Parganas, West Nadia and Hawrah) | 5600 | 16,724,824 | 2986.57571 |

| Madaran (Bankura, Vishnupur, South-east Burdwan) | 7049 | 9,403,400 | 1334.00482 |

| BIHAR | 55,478 | 221,848,096.5 | 4000.13346 |

| Bihar | 17,204 | 83,196,390 | 4835.8748 |

| Monghyr | 7745 | 29,625,981.5 | 3825.17515 |

| Champaran | 3376 | 5,513,420 | 1633.12204 |

| Hajipur (Patna) | 2479 | 27,331,030 | 11,025.0222 |

| Saran | 4028 | 16,172,004.5 | 4014.89685 |

| Tirhut | 6509 | 19,189,777.5 | 2948.19135 |

| Rohtas (Sasaram) | 6466 | 40,819,493 | 6312.94355 |

| Khokhra | 7671 | - | |

| ALLAHABAD | 34,613 | 212,427,565 212,427,819 | 6137.22645 |

| Allahabad | 2587 | 22,831,999 | 8825.66641 |

| Ghazipur | 1475 | 13,431,325 | 9105.98305 |

| Banaras | 587 | 8,860,318 | 15,094.2385 |

| Jaunpur | 6164 | 56,394,927 | 9144.21269 |

| Manikpur | 2600 | 33,916,527 | 13,044.8181 |

| Chunar | 1561 | 5,810,604 | 3722.36003 |

| Bartha Gahora | 10,781 | 7,262,780 | 637.664781 |

| Kalinjar | 5937 | 23,839,470 | 4015.40677 |

| Korra | 1333 | 17,397,567 | 13,051.4381 |

| Kara | 1588 | 22,682,048 | 14,283.4055 |

| AWADH | 26,463 | 201,364,203 | 7609.27344 |

| Awadh (Ayhodya/Faizabad) | 3063 | 40,956,347 | 13,371.318 |

| Gorakhpur | 8552 | 11,926,790 | 1394.61997 |

| Bahraich | 4137 | 24,120,525 | 5830.43872 |

| Khairabad | 4828 | 43,644,381 | 9039.84693 |

| Lucknow | 5883 | 80,716,160 | 13,720.238 |

References

- ICMOS. The ICOMOS Charter on Cultural Routes. 2008. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/images/DOCUMENTS/Charters/culturalroutes_e.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Duara, P. The Crisis of Global Modernity; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batty, M. Urban Modelling; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1976; Available online: http://www.casa.ucl.ac.uk/rits/batty-urban-modelling-2009.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Getis, A.; Getis, J. Christaller’s Central Place Theory. J. Geogr. 1966, 65, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jefferson, M. Why Geography? The Law of the Primate City. Geogr. Rev. 1989, 79, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabaix, X. Zipf’s Law for Cities: An Explanation. Q. J. Econ. 1999, 114, 739–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jacobs, J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, J.H.; Page, S.E. Complex Adaptive Systems: An Introduction to Computational Models of Social Life; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bettencourt, L.; West, G. A unified theory of urban living. Nature 2010, 467, 912–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrester, J.W. Urban Dynamics; MIT Press: Cambridge, UK, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Bourne, L.S.; Simmons, J.W. Systems of Cities; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Krugman, P. The Self-Organizing Economy; Blackwell Publishers: Cambridge, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Coffey, W.J. Urban systems research: An overview. Can. J. Reg. Sci. 1998, 21, 327–364. Available online: https://idjs.ca/images/rcsr/archives/V21N3-Coffey.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2020).

- Portugali, J. Self-Organization and the City; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, P.M. Self-organization and evolution in urban systems. In Cities and Regions as Nonlinear Decision Systems; Crosby, R.W., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 29–62. Available online: https://books.google.com/books?hl=zh-CN&lr=&id=u8PADwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=Cities+and+Regions+as+Nonlinear+Decision+Systems&ots=-QEtMlHbq3&sig=VFvDRratbZegGC4WqU26KbuAtdQ#v=onepage&q=Cities%20and%20Regions%20as%20Nonlinear%20Decision%20Systems&f=false (accessed on 1 November 2020).

- Wilson, A.G. A family of spatial interaction models, and associated developments. Environment and Planning A 1971, 3, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Allen, P.M.; Sanglier, M. Dynamic models of urban growth. J. Soc. Biol. Struct. 1978, 1, 265–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, A. Entropy in urban and regional modelling. In Handbook on Entropy, Complexity and Spatial Dynamics; Reggiani, A., Ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2021; pp. 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegener, M. Operational urban models state of the art. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 1994, 60, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedmann, J.; Wolff, G. World City Formation: An Agenda for Research and Action. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 1982, 6, 309–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedmann, J. The world city hypothesis. In World Cities in A World System; Knox, P.L., Taylor, P.J., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995; pp. 317–331. [Google Scholar]

- Castells, M. The Rise of the Network Society; Blackwell Publishing Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camagni, R.; Capello, R. The City Network Paradigm: Theory and Empirical Evidence. Contrib. Econ. Anal. 2004, 266, 495–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malecki, E.J. Entrepreneurs, Networks, and Economic Development: A Review of Recent Research. In Reflections and Extensions on Key Papers of the First Twenty-Five Years of Advances; Katz, J.A., Corbett, A.C., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2018; Volume 20, pp. 71–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Chen, L. Study on Urban Agglomeration Layout From the Network-City Perspective: A Case Study of Suzhou-Wuxi-Changzhou Urban Agglomeration. Resour. Environ. Yangtze Basin 2006, 15, 797–801. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F.; Ning, Y.M. The Autonomous Construction of Urban Network Research in China. Reg. Econ. Rev. 2020, 2, 84–92. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spodek, H. Studying the History of Urbanization in India. J. Urban Hist. 1980, 6, 251–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, R. Urbanization and Urban Systems in India; Oxford University Press: Delhi, India, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Thakur, S.K. Recent Studies in Regional Urban Systems in India: Trends, Patterns and Implications. In Spatial Diversity and Dynamics in Resources and Urban Development; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 39–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarti, D.K.; Rakshit, M. The Archaeology of Ancient Indian Cities; Oxford University Press: Delhi, India, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Chakrabarti, D.K. Archaeological Geography of the Ganga Plain: The Lower and the Middle Ganga; Permanent Black: Delhi, India, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lal, M. Settlement History and Rise of Civilization in Ganga-Yamuna Doab, From 1500 BC to 300 AD; BR Publishing Corporation: Delhi, India, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Erdosy, G. Urbanisation and the Evolution of Complex Societies in the Early Historic Ganges Valley. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Allchin, F.R.; Erdosy, G. The Archaeology of Early Historic South Asia: The Emergence of Cities and States; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Raza, M.; Habeeb, A. Characteristics of Colonial Urbanization: A Case Study of Satellite Primacy of Calcutta (1850–1921). In A Reader in Urban Sociology; Rao, M.S.A., Bhat, C., Kadekar, L.N., Eds.; Orient Longman: Hyderabad, India, 1991; pp. 49–69. Available online: https://books.google.com/books?hl=zh-CN&lr=&id=fEwOQh41NZMC&oi=fnd&pg=PA49&dq=Raza,+M.++Characteristics+of+Colonial+Urbanization:+A+Case+Study+of+Satellite+Primacy+of+Calcutta&ots=at3V3ZeLfh&sig=YpL8XGQB-YY_o4Z-fuu8iwQQcGk#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Habib, I. An Atlas of Mughal Empire; Oxford University Press: New Delhi, India, 1982; Available online: https://archive.org/details/Book_1109/page/n5/mode/2up (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Moosvi, S. The Economy of the Mughal Empire c. 1595, A Statistical Study; Oxford University Press: New Delhi, India, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Chandra, M. Trade and Trade Routes in Ancient India; Abhinav Publications: New Delhi, India, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Lahiri, N. The Archaeology of Indian Trade Routes: Up to c. 200 BC; Oxford University Press: Delhi, India, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Ray, H. The Southern Silk Route From China to India—An Approach From India. China Rep. 1995, 31, 177–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarti, D.K. The Ancient Routes of The Deccan and the Southern Peninsula; Aryan Books International: New Delhi, India, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.M. A Preliminary Research of the Sichuan-India Route. In Collection of Southwest Ethnic History Research, Volume 2; Institute of History of Southwest Frontier Nationalities, Yunnan University: Kunming, China, 1981. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lan, Y. The Southern Silk Route; Chongqing University Press: Chongqing, China, 1992. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Fang, G.Y. An Interpretation of the Historical Geography of Southwest China; Zhong Hua Book Company: Beijing, China, 1987. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Duan, Y. The Southern Silk Route: China-India transportation and cultural corridors. Thinking 2015, 41, 91–97. (In Chinese). Available online: http://www.bswh.net/images/news/dylw_10&ZD087.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Huo, W. The formation, development and historical significance of “Plateau Silk Road”. Soc. Sci. 2017, 11, 19–24. (In Chinese). Available online: http://www.silkroads.org.cn/portal.php?mod=view&aid=13089 (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Luo, Q.; Zhu, Q. Research Review of “Southern Silk Road” Since the 20th Century. J. Chang. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2015, 3, 97–106+187. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Fan, J. The Research of Southern Silk Road Literature Status. J. Libr. Sci. Soc. Sichuan 2017, 3, 46–48. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ling, W.F.; Luo, Z.W.; Mu, J.H. A Review on the Study of the Ancient Tea Horse Road. Soc. Sci. Yunnan 2018, 3, 97–106+187. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Majumdar, S.C. Rivers of the Bengal Delta; University of Calcutta: Calcutta, India, 1942. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya, N.D. Changing Courses of the Padma and Human Settlements. Natl. Geogr. J. India 1963, 14, 62–76. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartzberg, J.E. A Historical Atlas of South Asia; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1992; Available online: https://dsal.uchicago.edu/reference/schwartzberg/ (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- ISLAM, K. Economic History of Bengal, C. 400-1200 AD. Ph.D. Dissertation, School of Oriental and African Studies, London, UK, 1966. Available online: https://eprints.soas.ac.uk/29147/1/10731242.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Center for South Asian Studies, Beijing University. Compilation of historical materials from China in Central and South Asia (Volume 2); Shanghai Classics Publishing House: Shanghai, China, 1994. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Battuta, I. Travels in Asia and Africa:1325-1354; Routledge: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Vandana, V. Urbanisation in North India During the Medieval Period (1556–1668 AD). Ph.D. Dissertation, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, India, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Gipouloux, F. The Asian Mediterranean: Port Cities and Trading Networks in China, Japan and South Asia, 13th–21st Century; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA, USA, 2011; Available online: https://books.google.com/books?hl=zh-CN&lr=&id=jIAKkMlFFQAC&oi=fnd&pg=PR1&dq=Gipouloux,+F.+The+Asian+Mediterranean:+Port+Cities+and+Trading+Networks+in+China,+Japan+and+South+Asia,+13th%E2%80%9321st+Century&ots=LAPEfrXwVB&sig=d1V4Kuw6qVOGEVzUvIFBwGMawVU#v=onepage&q=Gipouloux%2C%20F.%20The%20Asian%20Mediterranean%3A%20Port%20Cities%20and%20Trading%20Networks%20in%20China%2C%20Japan%20and%20South%20Asia%2C%2013th%E2%80%9321st%20Century&f=false (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Eaton, R.M. The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204–1760; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Colby, C.C. Centrifugal and centripetal forces in urban geography. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 1933, 23, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, M.; Krugman, P.R.; Venables, A. The Spatial Economy: Cities, Regions, and International Trade; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lowry, I.S. A Model of Metropolis; Rand Corp: Santa Monica Calif, CA, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Portugali, J. Self-Organization and the City; Springer-Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2000; Available online: https://www.jasss.org/5/2/reviews/turner.html (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Whitehand, J.W. British Urban Morphology: The Conzenion Tradition. Urban Morphol. 2001, 5, 103–109. Available online: http://www.urbanform.org/pdf/whitehand2001.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2022). [CrossRef]

- Allami, A.F.; Blochmann, H.; Jarrett, H.S. The Ain I Akbari; Gyan Publishing House: New Delhi, India, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rennel, J. A Map of the North Part of Hindostan; Laurie & Whittle: London, UK, 1794; Available online: https://earthworks.stanford.edu/catalog/ab4fd264-2168-4353-9611-820970a92778 (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Tan, Q.X. A Historical Atlas of China (Volume 2); Sinomap Press: Beijing, China, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, N.; Chandra, S. Religion, State and Society in Medieval India: Collected Works of S.Nurul Hasan; Oxford University Press: New Delhi, India, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, R. Sarais in Mughal India. Ph.D. Thesis, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, India, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Anjum, N.A. “Sarais” in Mughal India. Proceedings of the Indian History Congress 2010, 71, 358–364. [Google Scholar]

- Gommans, J. Trade and Civilization Around the Bay of Bengal, c. 1650–1800. Itinerario 1995, 19, 82–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, A. Towns and Cities of Medieval India: A Brief Survey; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, J.F. The Mughal Empire; Cambridge University Press: New Delhi, India, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, P.E. British Rule in India: Rule of East India Company 1600-1857; Reprint Publication: New Delhi, India, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ray, H. Trade and Diplomacy in India-China Relations: A Study of Bengal During the Fifteenth Century; Sangam Book Limited: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Pommaret, F. Ancient Trade Partners: Bhutan, Cooch Bihar and Assam (17th–19th Centuries). J. Asiat. 1999, 287, 285–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N. Assam-Bengal Trade in the Medieval Period. J. Econ. Soc. Hist. Orient 1990, 33, 169–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, H. Trade and Trade Routes Between India and China, c.140 BC-AD 1500; Progressive Publishers: Kolkata, India, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, D. Proofreading and Annotation of Man Shu; Zhong Hua Book Company: Beijing, China, 1962. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, B. Horses, Silver, and Cowries: Yunnan in Global Perspective. J. World Hist. 2004, 15, 281–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharyyan, N.N. The History of Mediaeval Assam (AD 1228 to 1603). Ph.D. Dissertation, SOAS University of London, London, UK, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Baruah, S.L. A Comprehensive History of Assam; Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd.: New Delhi, India, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Michell, G. (Ed.) Brick Temples of Bengal: From the Archives of David McCutchion; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta, G.; Panja, S. (Eds.) . Archaeology of Eastern India: New Perspectives; Centre for Archaeological Studies and Training: Kolkata, India, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Van Schendel, W. Spatial Moments: Chittagong in Four Scenes. In Asia Inside Out; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015; pp. 98–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokhale, B.G. Early Buddhism and the Urban Revolution. J. Int. Assoc. Buddh. Stud. 1982, 5, 7–22. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, R.S. Urban Decay in India, c.300–c.1000; Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers: New Delhi, India, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Ray, A. Address of the Sectional President: Urbanisation in Medieval Bengal C. AD. 1200 to C. AD. 1600. Proc. Indian Hist. Congr. 1992, 53, 135–180. [Google Scholar]

- Ray, A. Presidential Address: Urbanization in Bengal. Proc. Indian Hist. Congr. 1987, 48, 9–46. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, K.N. Urban Development in India; Abhinav Publications: New Delhi, India, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Hosten, H. Travels of Fray Sebastien Manrique 1629–1643, A Translation of the Itinerario de las Missiones Orientales (Volume I): Arakan; Routledge: Lodon, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Thakur V, K. Trade and Towns in Early Medieval Bengal (c. AD 600–1200). J. Econ. Soc. Hist. Orient 1987, 30, 196–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.M. Saints of East Pakistan; Oxford University Press, Pakistan Branch: Dacca, Bangladesh, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Spate, O.H.K.; Learmonth, A.T.A. India and Pakistan: A General and Regional Geography, 3rd ed.; Methuen: London, UK, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Bertocci, P.J. Elusive Villages: Social Structure and Community Organization in Rural East Pakistan. Ph.D. Thesis, Michigan State University, East Lansing, Michigan, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Capello, R. The city network paradigm: Measuring urban network externalities. Urban Stud. 2000, 37, 1925–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelen, G.; White, R.; Uljee, I. Integrating constrained cellular automata models, GIS and decision support tools for urban and regional planning and policy making. In Decision Support Systems in Urban Planning; Timmermans, H., Ed.; E&FN Spon: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

| Colby’s Attribute Classification of Driving Forces in Urban Development | Classification of Driving Factors of City Network Evolution in This Study | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Type | Dynamic Property | Functional Movement | Dominant Driving Factor | Key Indicator |

| Centrifugal Force | The space force | Centre development space is insufficient and the situation of evacuation to the outer vacant site | industry and commerce | Flourishing economic exchanges facilitated the spread of manufacturing, commerce, distribution and other functions from the large cities of the central Ganges to small and medium-sized towns. |

| The site force | The heavily modified and intensively used landscape of the central area is balanced by the relatively unchanged but rarely used landscape of the periphery | |||

| The situational force | The tendency to move to peripheral areas with better functional division due to the unsatisfactory functional division of the center | |||

| The force of social evaluation | The trend of moving to the lower cost and more free periphery due to the high pressure and high cost of development in the central area | |||

| The status and organization of occupance | The central area cannot meet the traffic demand and the trend of turning to the outside to seek convenient transportation facilities | industry and commerce, geographical environment | The “Poliscratic” strategy and expanded transport systems facilitated the development of border trade hubs and towns. | |

| Human equation | A strong impulse to move outwards, generated by religious belief, political power, etc. | Ideology and culture | Land reclamation, migration and the development of grassroots autonomous organizations led by religious leaders promoted the creation of new towns. | |

| Centripetal Force | site attraction | The strong attraction of the natural landscape in the central area | political system, geographical environment | The attraction of the Ganges River and the enhancement of the land transport system facilitated the development of the central towns at the land and water route junctions. |

| functional convenience | Multiple functions are concentrated at the same point or interregional transportation hubs are located | |||

| functional magnetism | The clustering of similar industries in the central area | industry and commerce | Economic exchanges promoted the clustering of manufacturing industries in the central Ganga plain, commercial ports in the western Delta, and trade and distribution centres in the northern Delta. A number of world-renowned cotton textile centres have developed along the Ganges. | |

| functional prestige | Large scale of similar functions in the central area to produce a regional characteristic | political system, Ideology and culture | The “poliscratic” strategy set up the development of towns as provincial administrative centres; The continuation of towns as famous religious centres. | |

| Human equation | Political power, traditional culture, religious customs and other adherence to the central area | |||

| Route | North India Section | Nepal Section | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Route 1 | Allahabad–Mirzapur | –Sasaram | –Patna–Lalganj–Muzaffarpur | –Mithila–Bhadgaon (or Bhaktapur)–Kathmandu |

| –Buxar–Arrah | ||||

| Route 2 | Allahabad–Lucknow–Ayodhya (or Faizabad)–Bansi–Birdpur | –Lumbini–Kathmandu | ||

| Route | Place |

|---|---|

| Waterway | Gaur–along the Brahmaputra River to Assam |

| Land Route 1 | Gaur–Dinajpur–Goalpara–Barpeta–Guwahati–Tizpur–Naogaon–Sibsagar |

| Land Route 2 | Gaur–Fatehabad–Dacca–Sonargaon–Mymensingh–Sylhet–Jaintia hills–Sibsagar |

| Bengal–Sikkim/Bhutan Section | Tibet Section |

|---|---|

| Dajeeling–Rabdentse–Yuksom–Tumlong, Sikkim–Chumbi Valley | –Nathula Pass–Yadong–Phari–Gyangze–YamdrokTso– Yarlung Zangbo River (Brahmaputra River in Tibet)–Lhasa |

| Gyangze–Shigatse | |

| Rangpur, Beangal–Alipur Duar–Buxa–Paro | –Shigatse–Lhasa |

| Rangpur–Hajo, Assam–Dewangiri, Bhutan–Trashigang, Bhutan–Manas River Valley, Bumthang | –Lhasa |

| Rangpur–Hajo | –Tawang–TseDang;–Yarlung Zangbo River–Lhasa |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, X.; Dong, W. Spatial Evolution and Driving Mechanism of City Networks in the Middle and Lower Ganges Valley from the 16th to the Mid-18th Century. Land 2022, 11, 2016. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11112016

Wang X, Dong W. Spatial Evolution and Driving Mechanism of City Networks in the Middle and Lower Ganges Valley from the 16th to the Mid-18th Century. Land. 2022; 11(11):2016. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11112016

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Xihui, and Wei Dong. 2022. "Spatial Evolution and Driving Mechanism of City Networks in the Middle and Lower Ganges Valley from the 16th to the Mid-18th Century" Land 11, no. 11: 2016. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11112016

APA StyleWang, X., & Dong, W. (2022). Spatial Evolution and Driving Mechanism of City Networks in the Middle and Lower Ganges Valley from the 16th to the Mid-18th Century. Land, 11(11), 2016. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11112016