1. Introduction

Ibiza is an island (

Figure 1) with a huge dependence on tourism. Estimating the real economic weight of tourism in the island’s economy is difficult and the local press has reported values of 80%, 85%, or 90% of the GDP, between the direct and indirect effects. However, what is clear is that little economic activity on the island does not depend directly or indirectly on tourism. The various cultural activities on the island are also strongly linked to tourist activity and, for example, most handicraft markets and private galleries only open during tourist season. The 152,000 residents [

1] coexist with three million tourists [

2], with the number of people on the island oscillating between 150,000 in the winter and more than 320,000 in the summer. In 1950, just before the definitive development of tourism, the resident population was around 35,000. Before tourism development, the island had an agrarian subsistence economy that failed to produce surpluses until the final years of the 19th century [

3]. The beginnings of tourism in Ibiza date back to the first third of the 20th century, highlighting the period of 1931–1936. At that time, tourist volumes were small, at 5400 in 1935; at the same time, a small community of foreign residents began to reside there. This foreign colony stood out for its presence of representatives of the German artistic avant-garde, who resided on the island after fleeing from the German National Socialist government [

4]. Although they resided or were hidden there, some of the foreign residents left works on the island, such as Balneario de Talamanca, built in 1934 by Erwin Broner [

5]. Definitive tourism and the artists’ colony took off after the breakout of the Spanish Civil War and the post-war period in the 1950s [

6,

7].

The presence of artists, writers, and intellectuals, many of which were influenced by the Beat generation, attracted countercultural movements (beatniks and hippies). In the 1960s and 1970s, the media strongly impacted the presence of artists and hippies in Ibiza [

8], which also happened in other places such as Goa, Amsterdam, and Mykonos (stops on the route of the hippie movement from California to India and Nepal). The arrival of intellectuals and travelers to southern Europe, especially to the Mediterranean islands [

9,

10,

11,

12], began at the end of the 19th century and continued in the early 20th century. These travelers were attracted by the myth of the Mediterranean, an archaic south, not industrialized, of light and sun, and linked to ancient cultures. In addition, an Orientalizing vision of Mediterranean societies predominated in these travelers, as opposed to the civilized center of the great European metropolises in the center and north of the continent. For them, it was an abandonment of their routines and the shortcomings of the known modern world that led them to these areas.

The authorities and entrepreneurs of the island realized the media interest they were receiving and the importance of this media impact in developing the tourism sector. The result was that they supported the artistic avant-garde and various activities derived from the hippie movement to differentiate Ibiza and make it known in Spain and abroad [

13]. This powerful promotional use was the main difference compared to other regions with a hippie presence, creating the myth of Ibiza as an island of freedom, harmony, and nightlife [

14,

15]. This use of avant-gardes and artists for the promotion and differentiation of the island was a novelty of which Ibiza was a pioneer.

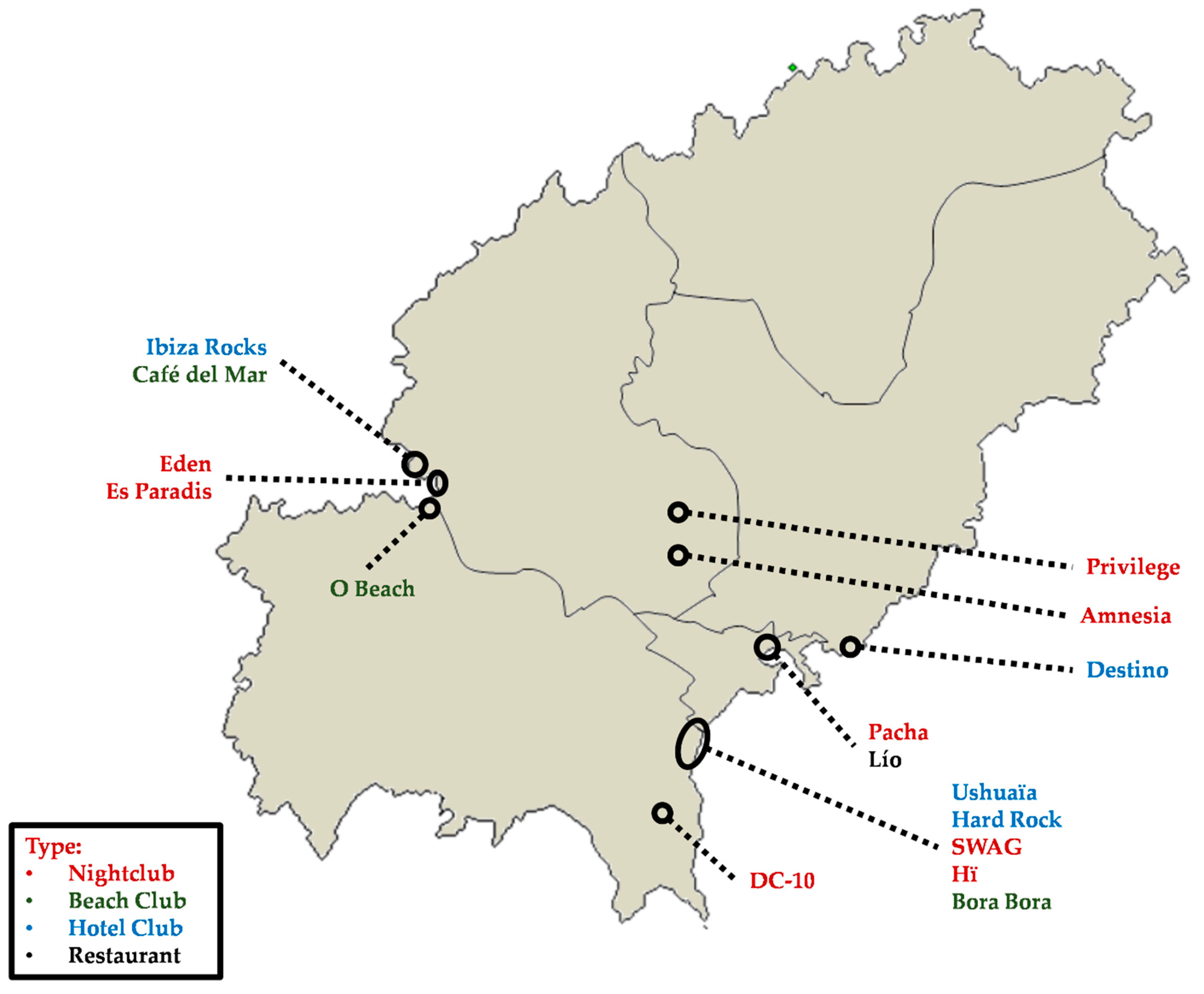

At present, Ibizan society is strongly dependent on tourist activity and is subject to the seasonal cycles of beach tourism. Ibiza tourism focuses on the offer of sun, sand, and sea, differentiating itself from other summer destinations with the offer of nightlife (

Figure 2), luxury tourism, and other elements derived from the hippie presence, which are discussed below. The local society has some of the worst education and formal studies ratios in Spain, due to the ease of finding unskilled jobs in the tourism sector. There is a certain informal cultural preparation based on the interaction of a cosmopolitan society and a great fondness for travel for an important part of the residents. All of this creates an environment conducive to alternative cultures that is not prone to promoting more formal and technological research and development.

The object of this paper is to expose the changes and cultural continuities caused by the presence of hippies and artists throughout the 20th century on Ibiza and to review the origins and current situation of various activities that are considered legacies of hippies and artists: art exhibitions, handicraft markets, and adlib fashion. These economic activities are part of the tourism supply and are an element differentiating the Ibizan image.

3. Intellectuals and Counterculture in the 20th Century

In the 19th and 20th centuries, intellectuals and artists arrived at many points in the “south”, and Ibiza was one of these points at which they arrived in the 20th century. Artists and intellectuals, such as Rafael Alberti, Walter Benjamin, Albert Camus, Le Corbusier, Corneille, Bob Dylan, Peter Finch, Errol Flynn, Walter Gropius, Raoul Haussman, Elmyr de Hory, Clifford Irving, Bernhard Kellerman, Erwin von Kreibig, Joan Miró, Jack Osgood, Ellliot Paul, Roman Polanski, Josep Lluís Sert, Adolf Schulten, Tristan Tzara, Mario Vargas Llosa, Orson Welles, and Wols [

4,

7,

15,

17,

18] were among them.

The first colonies of Europeans living in Ibiza appeared in the 1920s [

19]. However, the first wave of intellectuals, scientists, and refugees arrived in the 1930s. In those years, botanists, zoologists, archaeologists, and philologists came to study the peculiarities of the island, and the painters, photographers, musicians, writers, and architects came in search of refuge or a quiet place to create their works [

6]. The rise of German Nazism in 1933 led to the arrival of artists and intellectuals who left Germany due to either their Jewish roots or their intellectual avant-gardes [

4].

In the Spanish Second Republic (1931–1936), relatively few political convulsions occurred in Ibiza compared to other parts of Spain, due to the social and political configuration of the island. The intellectuals who came to Ibiza did not do so with the intention of contacting political groups with similar ideologies, unlike the avant-gardes of Barcelona, Madrid, and Valencia. Among the artists and intellectuals were members of the German avant-garde: Raoul Hausmann, Erwin Broner (Erwin Heilbronner), Will Faber (Wilhelm Faber), Erwin von Kreibig, and Wolfgang Schulze “Wols”. They escaped from the Nazi regime and had contempt for avant-garde art, which they called

entartete kunst (degenerate art). The writer and philosopher Walter Benjamin was also among them [

4,

5,

15].

Artists who arrived in the 1930s were characterized by an unquestionable relevance within the European avant-garde [

5]. They represented the first contact of Ibiza with contemporary art and began what would be a constant in the art of Ibiza until the 1980s: the predominance of foreign artists, forming a cosmopolitan and heterogeneous community that was disconnected and ignorant of the social and economic reality of the island. The artists were captivated by the human and natural landscape but, in their vision of Ibiza, there was an idealism in the contemplation of rural life and “they do not entertain to state the health deficits of houses” [

20] (p. 60). Many artists were attracted by the island’s exoticism, Mediterranean myth, and the low cost of living. However, the real Ibiza was economically underdeveloped; the emigration, the illiteracy, and the poor infrastructure were invisible to them [

4]. In turn, this small community of foreigners had an insignificant impact on the local community and culture; its effects were longer term.

The Spanish Civil War stopped the process of the creation of an artists’ colony. In August 1936, when they left the island, there was no significant presence of foreigners until the 1950s [

15,

18]. As of 1953, the island received new members of avant-gardes [

18].

At the end of the 1950s and during the 1960s, a community of artists and bohemians was formed, which, according to Carl van der Voort, consisted of 400 artists of 35 or 40 different nationalities [

13]. The bohemian atmosphere of the island was created by foreigners and Spaniards belonging to the world of art and was characterized by the coexistence and mutual ignorance of people from different ideologies, professions, and origins, by apparently contradictory situations, and by a strong isolation from the rest of Ibizan society who were more traditional and culturally lagging [

7]. In addition, there were two different social environments [

21]. Most of the bohemian artists were based in the city of Ibiza, following the tradition that had started in the 1930s. Within the social orbit of the artistic world in the city were groups such as the Ibiza 59 group and the Puget group. Sant Antoni had fewer artists but was more cosmopolitan and touristic and was the destination for snobs and people who loved to party [

21].

In 1959, the Ibiza 59 group was created, which was initially constituted by Erwin Broner, Hans Laabs, Erwin Bechtold, Katya Meirowsky, Bob Munford, Egon Neubauer, Bertil Sjöberg, and Antonio Ruiz [

5]. In 1962, the Puget group was created, which was composed of local artists: Vicent Calbet, Vicent Ferrer Guasch, Antoni Marí Ribas, and Antoni Pomar [

5,

18]. The Puget group was the response of local artists to the creation of the Ibiza 59 group [

5,

15]. With the Puget group, the emergence of an avant-garde artistic culture based on the local society was evident. From 1965, the central administration was involved in the promotion of avant-garde art with the Biennial of Art from 1964 [

18] and the creation of the Museum of Contemporary Art in 1968 [

6], both in the town of Ibiza. The reason for this promotion was to take advantage of the link between Ibiza and avant-garde art to promote tourism [

5,

15].

The tourist boom of the island occurred in the 1960s in conditions similar to those of other areas of the country [

22] and was characterized by the rapid growth in hotel beds [

23] and tourist arrivals [

6]. There was a moment of greater artistic production and greater media impact of the bohemian community, which coincided with the tourist boom. “During the 1960s, artistic creation would reach levels of hyperactivity and, at least until 1975, Ibiza went on covers and in reports almost daily, always breaking schemes. It lasted little, but the move was very intense, it was a shock” [

18] (p. 78).

However, the avalanche of artists did not offer results in all cases. Many of the artists spent all their time in bars and camouflaged among pseudo-intellectuals and opportunists. Among the foreigners who spent part or all of the year on the island were writers, photographers, and columnists, whose photos and texts were published in the European and North American media [

18]. They described artists’ lives as exciting and the island as an exotic and paradisiacal place. Ibiza was an archaic place and a paradise idealized by non-Ibizan people, due to an attitude of disillusionment with the western modern world [

5,

15].

At the end of the 1960s, Ibiza was no longer a “secret and calm refuge” and became a multitudinous point of passage for the hippie movement. “The hippie movement was stupid” [

18] (p. 75), said Carolyn Cassidy years later. The artists and intellectuals of the 1950s belonged to the beatnik universe. “The hippie movement was a vulgarization at ground level, to the bottom, of the Beat movement, but with more light, sound and colorful and, obviously, with more repercussion in the media” [

18] (p. 76).

These same doubts existed about the artistic world of that time and, especially, about the local artist community, to the point that Orson Welles dedicated one of his works to this subject, F for Fake, in 1973. This docudrama focuses on the art forger Elmyr de Hory, who had lived on Ibiza Island since the early 1960s.

The 1968–1974 period represents the classic era of counterculture and has become a model that was followed by subsequent movements. As a part of the exodus of European and North American members of the counterculture, Ibiza became an enclave of the hippie movement. The arrival of hippies reached its apex between 1973 and 1974 [

7], with a later decrease in arrivals, increase in returns, and a mutation of the community toward more integrated behavior in the economy and local society, something that also happened in other regions where a countercultural community had been established [

8]. From that time, various legacy elements of the hippie movement have been part of the local culture and the international image of the island. It is impossible to exclude this intangible cultural heritage from today’s society without falling into static, tribal, and fake views of Ibizan culture.

Hippies who arrived in Ibiza were characterized by being from great western metropolises, with an average age of twenty to thirty years [

24], with a high educational and cultural level [

8], and whose previous professional activity could be categorized as the medium and high categories in the cultural and artistic sphere [

25]. Some of them settled on the island permanently and others continued their trips onward [

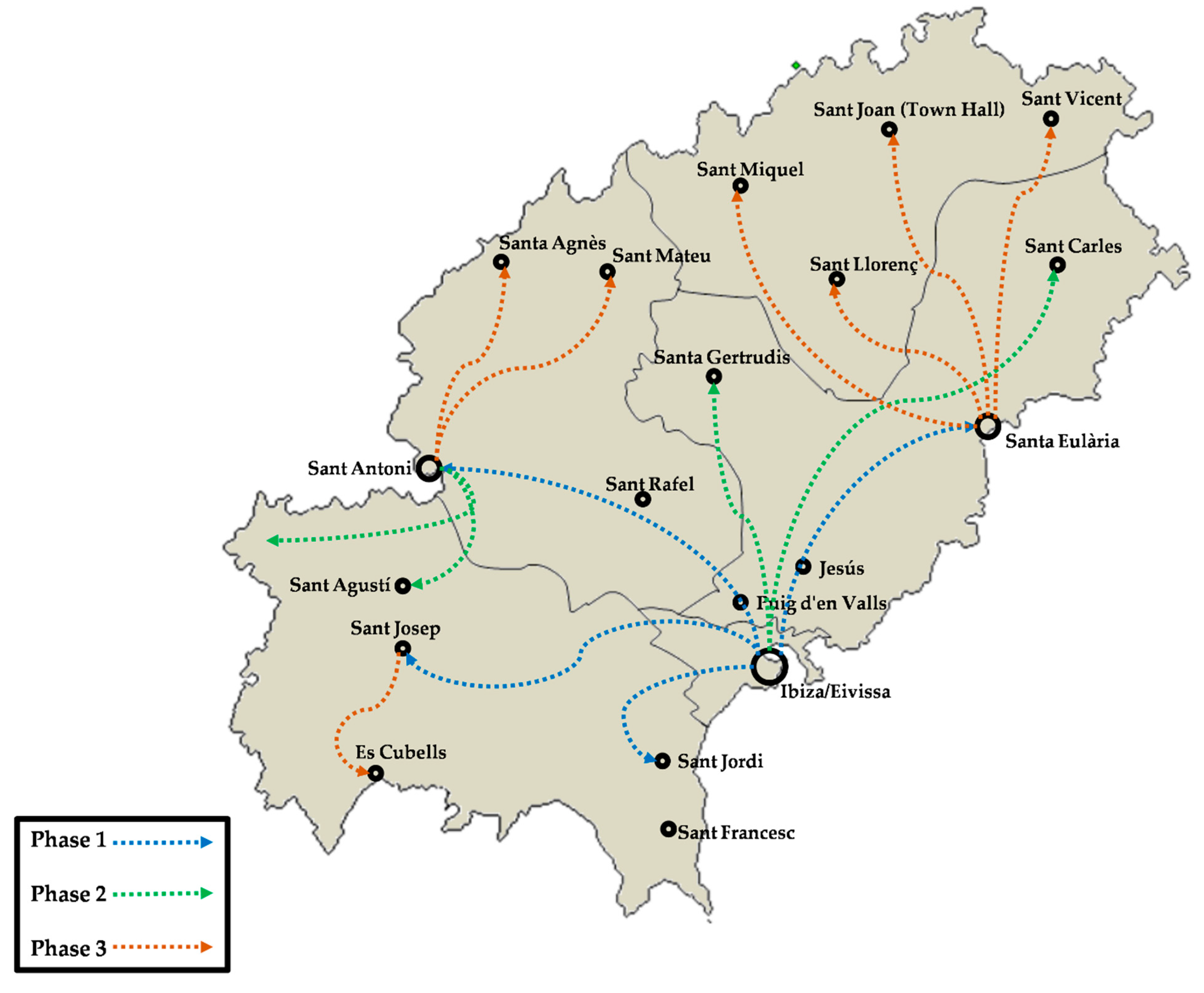

8]. At first, hippies concentrated in the city of Ibiza, Sant Antoni, Santa Eulària, and the areas of Sant Josep and Sant Carles (

Figure 3), following the same pattern of geographical distribution as the artists and beatniks in the 1950s [

8,

18]. There was a preference among hippies for immediacy, the natural and colorful, spontaneity, irrationality, and playfulness, easily perceptible in all facets of life [

26].

The native population and the hippies had little contact and different values, making it almost impossible to achieve fluid communication. In those years, the local population underwent a rapid transition from a predominantly agrarian society that was poor and had material and educational deficiencies to a society focused on tourism. Although during the hippie presence (the late 1960s and early 1970s) the island’s economy was already focused on tourism, the memory of the previous life was recent and the young people who worked in hotels and restaurants had lived in poverty in their childhood, marking their way of thinking and acting. For their part, the parents of these young people did not make the labor transition from agriculture to tourism, but they understood and supported their children in this labor and social transition. However, there were cultural loans between both groups that went beyond the unidirectional approach imposed by the theories of the time [

27]. For local people, everything that meant modernity was full of positive connotations. The desire to copy tourists was due to the desire to imitate modern societies, as the local people were tired of traditional material shortages. With these new arrivals, the local people were able to obtain jobs in the tourism sector. The Ibizan people started a life with greater material comforts and expenses. For local people, the city and the work depicted their ideals of life [

8].

On the contrary, the hippies idealized the rural world and the traditional society. Ibiza and its society were the materialization of their ideal of life: a unified and familiar world, as open as it was immobile, in contrast to the anonymity and agitation of great metropolises. The hippies took the indigenous way of life as a model; they sewed their clothes, ate vegetarian food, etc. [

8]. The peasant existence was moderated by austerity, but hippies prioritized hedonism and the enjoyment of the present. Dresses were complemented with capricious adornments; rustic benches were covered with tapestries, fabrics, and cushions; they celebrated parties and spent on whims, etc., which contradicted the way of life they claimed [

8]. This apparent contradiction was influenced by a search for an ideal lifestyle or, at least, a lifestyle better than the previous one [

28,

29], and, for this, they arbitrarily combined elements of various cultural contexts.

Within a few years, the hippies experienced the effects of the social change caused by tourism. The impossibility of subsisting on the market margins forced them to reconsider their situation. Most left the island. Some resumed their way east, others returned to their countries of origin to rejoin their previous lives, and those who stayed had to adapt to the economic reality [

30]. The economic reality implied a “conventional” life with a 1960s aesthetic, typical of the hippie movement.

The period of 1972–1974 was the beginning of Ibiza’s integration into the economic game. In this case, the local society was the modifier of the behavior of the newcomers and not vice versa, as the theories proposed [

27]. In addition, the legal-administrative pressure intensified, reaching its maximum between 1978 and 1980 and forcing foreigners to regularize their situation or to live with insecurity [

7]. However, these changes were not just about adapting to a new economic and political situation. The hippies had aged and had family under their care and aspired to a certain stability. In the small towns of the northwest and north of the island, there were reports of these adaptation experiences. Families with children enrolled in the small schools of these towns and whose members worked in various more or less conventional professions. Among these people, some were successful in the craft markets of Las Dalias or Es Canar, maintaining a certain connection with their origins, but many opted for jobs that were “opposed” to their philosophy of life, such as civil servants, usually in low-level positions. Another element that discouraged and forced them to change was the living conditions. Many went from marveling at the austere and primitive life to hating it with the same strengths and arguments with which the Ibizan people hated it [

8].

The implemented reconversion strategies were more conditioned by the social origin of the individuals than by their personal aptitudes or their initial training [

7,

8]. Whereas those who had capital to invest were oriented toward lucrative investments, business purchases, the foundation of companies, etc., the most vulnerable were satisfied with a worker’s salary or the scarce earnings produced by the exercise of precarious activities. Thus, the process of the hippies’ integration in the local economy revealed the inequalities that, until then, had remained hidden. Two professional branches reached certain prominence in Ibiza and acted as legacies of the image extended by the counterculture and as a refuge for those who wanted to be as close as possible to the utopia pursued by hippies: handicrafts and fashion [

8].

Handicrafts, represented by works in leather, wood, cloth, jewelry, etc., became famous with the hippie movement. The foreigners living on the island during the hippie era had a great fondness for handicrafts as an occupation, since it met their creative needs while granting them a source of income that needed almost no prior knowledge [

8]. However, the new panorama that was being forged since the mid-1970s with tourist development on the island was a clientele with limited buying power, strong competition, and an increase in the cost of living, so the artisan’s patient work was no longer profitable [

7]. Faced with this situation, some artisans refused to change, experiencing significant material difficulties, but most opted for serial production [

8], causing subsequent disputes between “true” artisans (they make what they sell) and “fake” artisans (selling products manufactured by others).

The women who arrived with the hippie movement considered the clothing of the native women to be full of charm, and they combined different pieces of peasant clothing with handicrafts (sandals, leather bags and belts, jewelry, handkerchiefs, etc.), making it something new. Transgressing the rules led to combinations that, over time, have become a symbol of the Ibizan counterculture. The combinations used by hippies in their clothing were the inspiration for many designers who started to create clothes under the Adlib brand. Adlib (ad libitum) fashion was a novelty of the 1970s, a consequence of the hippie movement, and the self-proclaimed legacy and testimony of this countercultural community.

Adlib Fashion Week was the main element of local designers’ promotion. In the 1970s, Adlib fashion was already conceived as a tool for tourism promotion abroad, demonstrated by the fact that First International Fashion Week, held in 1971, was financed by the Ministry of Information and Tourism [

13]. Although it was later professionalized, the first objective was to create another reason to talk about Ibiza and its cosmopolitan environment and freedom.

Since the 1970s, hippies have also had an entertainment function in the hippie markets. The markets of Las Dalias and Es Canar are important tourist attractions, due to the media use of the hippie presence. Hippies are allowed to dream about the eventuality of substantial income in exchange for a slight “excess” in the exotic sense: dresses, ornaments, make-up, etc. To this ritualized animation it is necessary to add the specific manifestations that hippies unite with the hope of obtaining some material benefit and to attract an insular public toward their beliefs [

8].

Finally, it is worth mentioning the symbolic use of the hippie presence by tourism promotion agencies [

15]. In the search for an original and competitive image of Ibiza, characteristic elements, such as the establishment of artists and craftspeople, markets, hippie fairs, naturism, Adlib fashion, etc., were used for the international market. Artists and members of the countercultures established on the island became part of the folkloric elements, together with the local tradition, which were used as an attraction in tourist advertising [

8]. Notably, the legacy of the hippie movement is much better known nationally and internationally than the local traditional folklore and culture.

4. Art and Handicrafts Today

The artists’ colony and hippie community of the mid-20th century had a lot of media impact, especially in the 1960s and 1970s [

15] and created various new activities that are part of the actual tourism supply. These activities sustained a differential image of the island as a tourist destination and are considered direct legacies of one or both communities. These activities are:

Galleries and art exhibitions: During the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, internationally renowned artists who resided on the island generated media impact. Although there were exhibitions, art was exported. Local artists were more exposed outside the island than outside artists were exposed inside. Since the 1970s, exhibitions of artists from abroad have been increasing on the island, and with the development of luxury tourism, an interest in exhibiting on the island to sell and promote art internationally began, but this tourism was not as important as was believed and was not characterized by having specific preferences beyond luxury consumption.

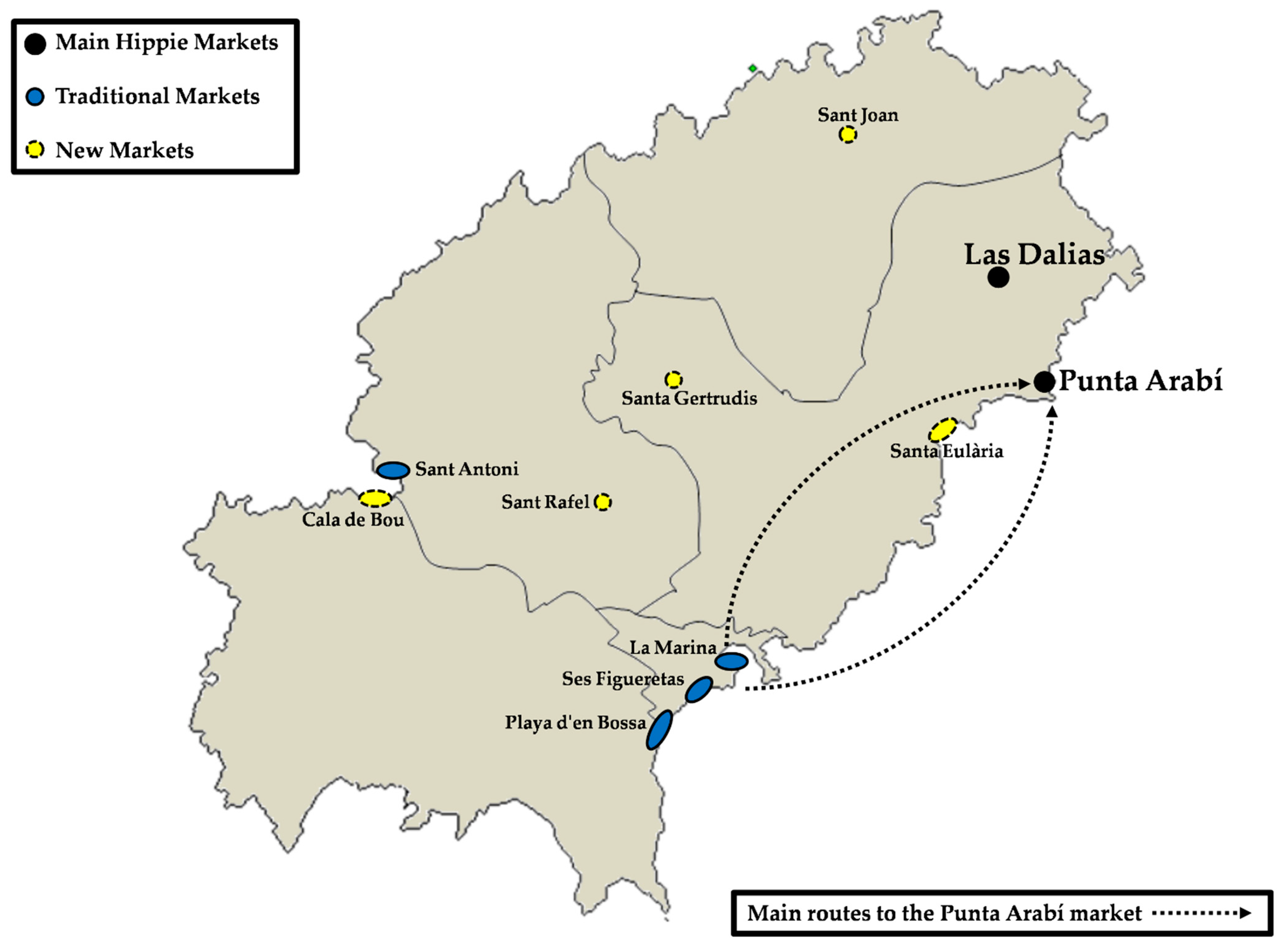

Hippie markets and handicraft markets: Handicraft markets began to thrive in the hippie era, although this activity had existed before. Since then, new handicraft markets have been created with the aim of boosting various tourist or urban zones. Currently, it is possible to find all kinds of products in these markets, and the controversy between real and fake artisans continues. Some are successful, such as Es Canar and Las Dalias. Others have acceptable results and some are not profitable.

Adlib fashion: Inspired by traditional clothing, designers who created the autochthonous fashion that is part of the island’s image appeared at the end of the 1960s. A part of these local designers is included under the Adlib umbrella brand, but another significant part is not included, although it has stylistic similarities to Adlib fashion. For fifty years, designers have appeared and disappeared, but this activity has been maintained.

Clubs and beach clubs: The offer of nightclubs and other nightlife venues is considered the legacy of the parties organized by the artists and hippies in the 1960s. Some clubs have a direct origin in houses or restaurants where improvised parties were held in the 1970s, as in the case of Amnesia and Privilege. In the case of beach clubs, such as Café del Mar, their offer is based on the hippies’ habit of contemplating the sunset.

The result is that a large part of the elements differentiating Ibiza as a destination for sun and sand are legacies of the presence of the artists and hippies in the 20th century. Of these, galleries, handicraft markets, and Adlib fashion comprise the most direct inheritance.

4.1. Galleries and Art Exhibitions

Of the island’s offerings, it is possible to highlight the Museum of Contemporary Art of Ibiza (Museu d’Art Contemporani d’Eivissa (MACE)), located in the city of Ibiza. MACE’s origins are linked to the International Biennial of University Art, which began in 1964. After the success of the first two Biennials, organizers decided that in subsequent editions the winning works would be transferred to MACE. In 1968, the third edition of the Biennial was held in the museum, located in various halls of the city walls [

15,

31]. At present, MACE continues to be a benchmark for contemporary art in Ibiza and, in 2012, it was modernized and expanded.

In addition, the number of exhibition halls and art galleries has increased significantly in recent years. This growth has increased Ibiza’s importance in the artistic scene, both nationally and internationally. Large exhibition halls are located in relatively isolated places and small art galleries are located in the city center, showing a wide diversity in both techniques and artistic styles. The large number of art galleries and exhibition halls is due to the fact that many artists have found a place to be inspired and settled on the island. Another factor affecting this boom is that Ibiza has become a place of passage for people from all over the world and with varied interests, so it provides a favorable environment for this type of activity. Most activity in art galleries occurs in the summer months, with the most important exhibitions taking place during the months of June, July, and August [

13]. The art galleries taking advantage of the influx that the island receives during the summer months have, as a counterpart, the limitations that seasonality implies. In order to be able to receive public throughout the year, the galleries focused on a local audience rely on the local media and are always looking for new projects to stay in the spotlight.

After a relative crisis in the presence of artists and art galleries during the 1980s and 1990s, there has been a rebirth of exhibition spaces. At present, art galleries and exhibitions, both in galleries and in other establishments, are experiencing an important boost, due to the development of luxury tourism on the island. In Ibiza, there are art galleries with a clearly commercial focus, exhibition spaces managed by public entities, and art galleries of resident artists, in which only their works are shown. Exhibitions of great importance can be found in other spaces, such as hotels and restaurants, which incorporate contemporary art as an attraction.

4.2. Hippie Markets and Handicraft Markets

At the time of the hippie movement, there were already handicraft markets that appeared spontaneously in various places on the island, with the first in Patio de Armas of Dalt Vila (city of Ibiza) in 1966. Although they were not initially regulated, the legalization and establishment of agreements with the hippie artisans was sought from authorities and Fomento del Turismo, in order to take advantage of their presence for tourism promotion purposes [

13]. Many of the handicraft markets of that time disappeared years ago, but, since then, various handicraft markets or hippie markets have appeared throughout the island (

Figure 4).

It is necessary to highlight the hippie markets of Punta Arabí (Es Canar) and Las Dalias (Sant Carles) for their size, age, and media impact. Both markets are private initiatives. Throughout the summer, there are several handicraft markets in the streets of main tourist areas: La Marina (port of Ibiza), Ses Figueretas (seafront of Figueretas), Sant Antoni (seafront of Sant Antoni), and Playa d’en Bossa. They are managed from town halls and occur every day in the afternoon. These markets seek to liven up the late-night tourist atmosphere in their respective areas. More recently, handicraft markets have been created for tourism purposes in other areas: Cala de Bou (Bay of Sant Antoni), Sant Rafel (

Figure 5), Santa Gertrudis, Sant Joan, and Santa Eularia. These markets take place once or three days a week. In the case of Cala de Bou, they are promoted by neighborhood associations and managed by town halls. The latter have a very low number of visitors as they are starting up and are not yet consolidated.

The oldest and largest is the Hippy Market Punta Arabí. This market has its origins in 1973 and was organized by the managers of Hotel Club Punta Arabí, located in the area of Es Canar. In the beginning, there were only 5 stalls, but it has grown to more than 500 stalls distributed through the streets of the Club Punta Arabí residential area. This market sells antiques, fashion, handicrafts, handkerchiefs, jewelry, musical instruments, natural cosmetics, and original items brought from the east, etc. [

32]. This market is located within a gated resort and depends on the managers of the Punta Arabí urbanization for its continuity. In recent dates, this continuity has been in doubt, due to a change in ownership in the urbanization where it is located.

Las Dalias was a bar located in Sant Carles, just before reaching the town, and was opened in 1954 by Juan Marí Juan. Later, a party room was added, and tourist barbecues began to be held with flamenco shows in the 1960s and 1970s. Due to the hippie atmosphere, it was normal for the parties to be frequented by the artisans of Punta Arabí Hippy Market. Juanito Marí took over from his father in the early 1980s and created the Hippy Market in 1985, with 5 stalls that, over the years, have increased to more than 200 stalls. Hippy Market Las Dalias sells accessories, antiques, books, clothing, handicrafts, decoration, hammocks, handmade shoes, incense, jewelry, musical instruments, paintings, records, etc. [

33]. Currently, the management of the Las Dalias handicraft market is somewhat more proactive than that of the Punta Arabí handicraft market, launching new initiatives, both on the island (night markets) and abroad (market celebrations in other destinations).

The popularity of the hippie markets of Punta Arabí and Las Dalias is such that there is currently a waiting list to be able to obtain a stall. In these markets, if there is the possibility of opting for a stall, it is necessary to pass a selection process carried out by their managers, pay an annual fee, and fulfill a commitment to participate every day of the season [

32,

33]. It is a paradox how an element of countercultural and anticapitalist origin became an application of the most exacerbated capitalist competitiveness.

The thousands of visitors that arrive at these two street markets cause traffic problems on roads and kilometers of congested traffic. In the case of Punta Arabí, there are also boat routes that connect the city of Ibiza and Santa Eulària with Punta Arabí on market Wednesdays. The data for the rest of the street markets are much more modest.

4.3. Adlib Fashion

Adlib fashion businesses are small, and, in some cases, they are more a self-employment situation than the creation of a company. Therefore, these designer-entrepreneurs create their own designs and distribute them in their own stores, fairs, and representatives. They usually have a small atelier, in which the designer and some employees work, and, in some cases, their own store where they sell their products. In addition to their own atelier, it is common to use ateliers outside the island to meet the demand. There is an undetermined number of women working from home for the ateliers, but this number is difficult to determine. People who have worked in the sector for many years have acquired knowledge through self-study and experience, but, since 1995, Ibiza has provided specialized training in clothing design.

Although Adlib fashion is characterized as informal clothing, with light colors, transparencies, and lace, there are exceptions to this generalization. Diversity is wider in the types of products and lines they produce, although they always maintain the essential elements of Adlib fashion. As an example, there are businesses dedicated to leather, children’s fashion, bridal gowns, or embroidery. Adlib fashion has persisted, without losing strength, since the 1970s, due to its differentiation and because the nonessential elements of design have been changing to adapt to social changes. As such, the Adlib fashion that is currently marketed takes the basic elements of the 1970s, but there is a wider variety in their interpretation, resulting in a larger variety of products covered under Adlib.

In the case of clothing, a differentiation has been achieved through the Adlib collective brand, but its promotion is insufficient. The Adlib brand is well-known, mainly linked to the tourism supply, but knowledge about the Adlib product is scarce among residents and tourists. Consell de la Moda provides the main contribution of public administration of the clothing sector. The main function of Consell de la Moda is to organize promotional events and attendance to national and international fairs, which, due to their cost, are unattainable for designers by themselves. Consell de la Moda organizes all the joint promotional actions of Adlib designers. One of the events organized by Consell de la Moda is Adlib Fashion Week, held in May or June, which aims to inform residents and tourists about the designers’ styles for the current tourist season.

Currently, the Adlib brand includes eighteen designer-entrepreneurs producing clothing and accessories who concentrate their stores in the town of Ibiza, especially in the areas near the port (La Marina, Vara de Rey, and surrounding areas). It is an active sector that is not transparent to fiscal controls and is, therefore, reluctant to offer economic information. However, these eighteen designer-entrepreneurs each have a workshop and one or two small shops on average. This means that the Adlib includes between 20 and 30 small shops and between 50 and 100 workers (it should be noted that the island of Ibiza has more than 5000 businesses and 150,000 residents). Adlib fashion is a small economic sector but with a high importance in the tourist imagery.

5. Conclusions

The impact of tourist development on the island of Ibiza has been radical. Before the increase in tourism, a subsistence economy predominated, with small exports, centered on the primary sector and small farms; there was no significant presence of residents from outside the island, and there was little travel outside the island, among other characteristics. After tourist development, the society of Ibiza has become diverse in its origins, with people used to traveling outside the island, and it is dedicated to the tourism sector almost exclusively. Thus, between 1950 and 1980, changes in local society affected almost every aspect of life.

The artists and counterculture members (beatniks and hippies) are not unique to Ibiza [

17], but they created an intangible cultural heritage of higher importance for the island’s tourist image. Due to the mutual lack of awareness between the foreigners’ colony (artists, intellectuals, beatniks, hippies, etc.) and the local population, it was possible to generate an image of freedom and tolerance with a strong media impact in the 1960s and 1970s [

8,

15]. Since the 1950s, administrations and entrepreneurs have understood the possibility of using this phenomenon to differentiate the tourist image of Ibiza and have undertaken all actions possible to enhance the activities linked to these communities. More than preserving the legacy of the colonies of artists and hippies, the local authorities have focused on the inclusion of these elements in tourism promotion and on actions to maintain the legacy activities of these movements, which were listed in the previous section: The Museum of Contemporary Art—MACE (Eivissa, Spain) in the case of the artistic avant-gardes; town hall management of various handicraft markets in the case of crafts; the Consell de la Moda for the promotion of the Adlib brand and its designers, as well as organizing the Adlib Fashion Week. The preservation of the historical legacy through associations and museums has so far focused on local culture prior to tourism development and the arrival of countercultural groups.

The high media impact, both national and international, of the island would have been impossible without artists and hippies, since local administrations had few resources for promotion and advertising [

13].

Since the 1970s, various economic sectors have been created and are considered inheritors of the foreigners’ communities of the 1960s, and are a part of the current tourism supply and island image: art galleries, handicraft markets, Adlib fashion, etc. These sectors are not important in terms of activity in relation to the economy as a whole but are fundamental for Ibiza tourism. The empowerment of these elements for international promotion is the main difference between Ibiza and other destinations with a similar presence of artists and counterculture.

Exhibitions of contemporary art are beginning to occupy positions similar to electronic music in the island’s tourism offer. In addition, holding exhibitions on Ibiza is attractive due to the international media impact they can have and because some of the tourists are potential clients. Before, exhibitions were only held by resident artists and the market was outside Ibiza. Now, with luxury tourism, a local market that has effects and international attraction is beginning to form.

The coexistence of luxury tourism and the bohemian counterculture has existed for several decades on Ibiza. This coexistence is not entirely contradictory and fits into the profile of Bobos proposed by Brooks [

34]. The greatest risk of unsustainability may come from the presence of a type of tourism characterized by the new rich or new money who are not as loyal to brands, companies, or destinations.

The handicraft markets of Ibiza are surprising with a certain contradiction between the image they offer and the reality behind it. The degree of competitiveness in Punta Arabí and Las Dalias is high, generating a tense atmosphere among sellers. This is because some artisans have received significant income and achieved international renown in these markets. For organizers, the income is also important: fees for the stalls, parking prices, food sales, the organization of events, etc.

Art and crafts, as described above (for example, “true” and “fake” artisans), have followed a trend toward lower quality, taking advantage of the island’s popularity and an increased sale of industrial products, to the detriment of true handicrafts (in the case of hippie markets). Even in the production of traditional island products, quality has declined with their conversion into tourist souvenirs.

Adlib fashion has experienced vicissitudes throughout its history but is currently living a moment of relative prosperity, due to white weddings (nuptial celebrations in which all those attending wear white) and making wedding dresses. The main weak point of this sector is the small size of the businesses and the lack of collaboration among designers. Among the designers of the island, the closings of ateliers and bankruptcies are frequent. Sometimes, failures in management occur after commercial success. In addition, the political changes in local administrations and their effects in Consell de la Moda are not helping the promotion and empowerment of Adlib fashion.

All of these activities are characterized by being well-mentioned and known in the tourist promotions, but no studies have been conducted on them. The main limitation of this paper is that it is an approximation of these sectors, and for future lines of study, we propose the deepening of analyses of these sectors: their history, their current situation, their management, cases of success and failure, etc. One of the main difficulties for research is that these are sectors with a tendency to legal irregularities, which makes it difficult to obtain data.

Regardless of the economic sectors developed as a heritage of the community of artists and countercultures of the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, a largely intangible cultural imprint has remained that is characterized by increased freedom and unconcern in the way residents and tourists behave. This can be seen in small details, such as more casual clothes; greater tolerance toward provocative behaviors, for example, toplessness and nudism; greater interest in exotic, oriental, or foreign elements; great fondness for nightlife and travel; etc. All of this results in an atmosphere that visitors highlight as a differentiating element of Ibiza.