Abstract

Access to banking and financial services is defined by various international organizations as essential to ensure the development of countries and regions. However, this access is not always guaranteed, even in developed countries. Our study focuses on analyzing the current situation of several rural and depopulated areas of Castilla y León (Spain) in terms of access to banking services and cash. For this purpose, an initial spatial analysis has been carried out to compute the access to these services measured in kilometers needed to travel to access them. Subsequently, we included, as a possible solution, the access to these financial services through their implementation (as a cash back point) in the extensive Spanish network of pharmacies. The results obtained in the spatial analysis show that the introduction of the network of pharmacies as a point of access to cash means a significant reduction in the distance to travel in municipalities in rural and unpopulated areas in order to access cash. In the case of the province of Avila the distance would be reduced by 55%, in the province of Segovia the distance would be reduced by 38.5%, in the province of Soria the distance would be reduced by 20%, in the province of Palencia the distance would be reduced by 22%; and finally in the province of Zamora the distance would be reduced by 33%.

1. Introduction

Financial exclusion refers to the impossibility, inability, or lack of access to the most basic financial products and services, such as savings accounts, means of payment, credit, or insurance. As the World Bank points out, this concept, is one of the main risk factors for poverty worldwide. As an element contrary to financial inclusion, exclusion is a brake on economic growth, savings, and credit. On the one hand, financial inclusion is an essential factor, since its ultimate aim is to reduce poverty and, in turn, to stimulate prosperity [1]. On the other hand, the concept of financial exclusion is defined as a universal problem that especially affects the poorest individuals due to various factors such as limited access to administrative processes, geographical barriers, etc. [2].

The reasons and mechanisms for combating financial exclusion have been widely discussed in the academic world [3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. This reality is highlighted by the fact that almost half of the world’s adult population (3.5 billion inhabitants) does not have a bank account at a financial institution [10]. From an academic point of view, the way in which financial inclusion has traditionally been measured has been through different instruments. The multidimensional index of financial inclusion (MIFI) is one of them. The MIFI evaluates the degree of financial inclusion based on three dimensions: use, barriers (quality) and access. The MIFI evaluates the degree of financial inclusion of a country through eighteen World Bank indicators [1]. Based on these three dimensions, eighteen indicators are measured, allowing the MIFI to be considered as a harmonized index of financial inclusion comparable between countries for the same country over time. The three dimensions mentioned above refer to the eighteen indicators that determine the degree of inclusion:

- The first block refers to usage. It contains three fundamental indicators such as the existence of financial products, savings holdings, and credit holdings. This information is provided by the World Bank through the Global Findex [11].

- The second block refers to quality. It is based on four fundamental indicators: trust in the financial system, the cost of financial services, distance to access points and the documentation required.

- Finally, the third block refers to access. The indicators in this last block measure the number of personal service points (bank branches and the like) and access to services through machines such as ATMs and the like. This information is obtained from studies such as the International Monetary Fund’s Financial Access Survey (FAS). Thus, through this index access is measured by four fundamental indicators [12].

- The number of ATMs per 100,000 adults.

- The number of bank branches per 100,000 adults.

- The number of bank branches per 1000 square meters.

- The number of ATMs per 1000 square meters.

A distinction can be made between two types of financial exclusion: voluntary exclusion and involuntary exclusion. In the case of voluntary exclusion, potential users of financial resources have access to them, but prefer not to make use of them [13]. This is due either to a lack of need or for cultural or religious reasons [14]. The second type of exclusion, is the result of several factors already mentioned above: lack of sufficient income, discrimination against certain groups, the absence of branches because they are not commercially viable for financial institutions, high prices or inadequate products [9,13,15]. Logically, the probability of suffering financial exclusion increases for the lower income strata, women, part-time workers, the unemployed and, within them, those with a certain level of disability, pensioners, students, and single-parent families [9,15,16].

Both in the developed and underdeveloped countries there are situations of financial exclusion, but it is precisely in the underdeveloped countries where the consequences are aggravated. This is due to the fact that the inability of financing to reach the poorest strata is what destabilizes most of the official programs in the fight against poverty [16]. Specifically, 50–80% of adults in developing countries have inadequate access to financial resources [9]. In contrast, in the most advanced countries, more than 80% of households have an account with a financial institution [9]. The significance of financial exclusion is very important because its concentration in the most disadvantaged groups contributes to the generation and aggravation of social exclusion and poverty. Financial exclusion is closely linked to social exclusion since “social groups that cannot access financial services cannot, as a general rule, obtain any other type of social consideration, so that financial exclusion becomes an element that enhances other types of social exclusion” [4,17]. The European Commission defines financial exclusion as: “the process whereby people encounter difficulties in accessing and/or using financial products and services in the formal market in accordance with their needs and which enable them to lead a normal social life in the society to which they belong” [18,19]. In short, financial exclusion entails not being able to exercise social or economic citizenship, understood as that which incorporates socio-economic rights, a certain security of life and minimum standards. Obstacles to access and use of financial services can be classified into four types [20,21]: Elements of an economic and social nature that hold back the demand for financial services by a significant part of the population.

- Problems in the way the banking sector operates.

- Institutional deficiencies.

- Regulations that tend to distort the provision of financial services.

These obstacles give rise to different types of financial exclusion. In our study, we have focused on those obstacles related to spatial access. In the first place, we find geographic exclusion due to the absence of a financial institution in a territory [8]. Derived from the above, the exclusion called Redlining appears, which is financial exclusion based on geographical location; in this case due to territories excluded by financial managers given the conflictive nature of the place or the higher level of poverty [22].

In short, the consequences of financial exclusion at a general level in society entail a slowdown in economic growth, which increases the social exclusion of people living, above all, in rural and depopulated areas. However, there are other consequences at the individual level, such as difficulties in managing income and expenses, over-indebtedness, administrative and economic problems, greater tendency to poverty, unwillingness to save and stigmatization of people in a situation of financial exclusion.

In this paper, we have analyzed the existing financial inclusion in specific areas of Castilla y León, Spain, where there are realities of depopulation and aging; in order to ultimately provide measures to help improve this inclusion. Our proposal is based on the inclusion of pharmacies in these areas as points of access to cash via cash back.

2. Literature Review

In recent decades, the concept of financial exclusion has been the subject of growing interest in academia. In general terms, an approach to the concept of financial exclusion leads us to identify a situation characterized by limited access to conventional financial services by a certain percentage of the population. Authors such as [23,24] have defined the concept of financial exclusion as a complex phenomenon that arises in the individual as a result of the conjunction of a wide and varied set of factors. These same authors point out that there is a group of people at greater risk of suffering this exclusion, including single people or those living alone, people living in areas with lower population density, immigrants, and the poorest people. Other definitions refer to the situation in which certain individuals or groups find themselves as a result of their demographic, economic or social situation, which makes it impossible or difficult for them to access the acquisition and contracting of products and services marketed by the different financial intermediaries [25]. The relationship between ex-financial exclusion and social exclusion is also frequently discussed in the academic world [4]. When assessing the concept of financial exclusion, different degrees of amplitude are considered. Thus, a distinction is made between total exclusion: in this case the subject has no possibility of accessing financial services such as insurance, credit, bank accounts; and partial exclusion: in this case the subject is only deprived of access to those financial services that carry a certain risk for the entity that provides it, such as a loan [26]. Another of the main consequences of the processes of financial exclusion exists in the management of money itself since they do not have a bank account. In this sense, there are difficulties in storing the income received by families in a safe and efficient way, with greater ease of theft or loss [23,24]. Along with the problems derived from money management in the absence of financial instruments, the difficulty in saving is another of the main negative aspects, as it affects people’s security and flexibility in dealing with unforeseen events, as well as forcing them to forego payment for certain services that may be essential at any given time [2,27,28]. With respect to the indicators mentioned in the introduction, different authors have emphasized some specific indicator as being more representative of the concepts of financial inclusion and/or exclusion. Similarly, there is also extensive academic research on possible actions or instruments to improve the financial inclusion of certain sectors of the population. Several authors have studied those aspects that could help limit financial exclusion, focusing on technology; especially cell phones and internet access, and its continuous progress as an enhancer of new digital financial products and services [29,30,31]. In this sense, authors such as [31] point to the institutional framework itself as a limiting factor in the development of new technologies in the fight against financial exclusion. From another point of view, Lee highlights the existence of micro-credits as a fundamental factor, understanding these as small loans in terms of the amount destined to create an activity with which to obtain an income [32]. Authors such as [33] emphasize the relationship between financial inclusion and economic growth by pointing out that the fight against exclusion makes it possible to reduce poverty and, at the same time, generate an increase in general welfare by generating an increase in income. The relationship between financial inclusion and financial transparency has also been studied through payments on account (in this case replacing cash payments), which allow for more transparent transfers or payments. In the same vein, Lewis relates financial inclusion to investment by allowing savings rates to be channeled into investment through loans [34]. This greater savings capacity also has a direct influence on the consumption of the most disadvantaged households [35], which increases the welfare of families with fewer resources and access to basic resources such as health and sanitation [36] and, ultimately, greater business investment to cope with this increase in consumption [37]. Finally, studies in global terms have linked the results of increased access to credit to well-being, decreased depression, increased trust in others and increased decision-making power of women in the household [38].

On the other hand, empirical evidence shows that rural areas subject to strong demographic stresses, in particular population aging and low population density, are particularly at risk of financial exclusion [39,40].

The consequences of financial exclusion in rural areas have also been studied. Ho and Berggren [41] examine the impact of bank branch closures on entrepreneurial activity beyond the administrative boundaries of a municipality. These authors identify some influence between proximity to bank branches and new firm formation. Along the same lines, Alessandrini et al. [42] conclude that a greater functional distance between banks and local economies tightens financing constraints, especially for SMEs. Moreover, such a restriction is not compensated by a higher credit availability caused by the reduction of the operating distance. Other authors, such as Coppock [43] focus their study on the impact of financial exclusion on households in rural England, and Panigyrakis et al. [44] do so in remote island territories located in Greece, where the dissatisfaction of citizens residing in these areas is identified. Other research has designed a methodology to identify the areas affected by the difficulty of access to financial services. For example, Náñez Alonso et al. [45] propose the construction of an index to detect rural areas at risk of financial exclusion, taking the Spanish region of Ávila as a case study. The results of this study show that more than 80% of the municipalities in this area have difficulties in accessing financial services.

On the other hand, accelerated economic digitalization is transforming traditional models of economic and social organization [46]. The financial sector is no stranger to this transformation. On the contrary, it is one of the sectors most affected by the changes and opportunities offered by digital technologies. In this context, several studies have analyzed the impact of banking digitalization on digital exclusion in rural areas. Authors such as Jorge-Vázquez et al. [47] conducted a study to identify the degree of penetration of digital financial services in rural areas and the behavioral pattern of electronic banking users. Others, such as Náñez Alonso et al. [48] analyze the possible acceptance of a central bank digital currency (CBDC) in rural areas as an alternative to the difficulties of access to cash in areas at risk of financial exclusion. In the following section, after analyzing the existing literature on the concepts of financial inclusion and exclusion, a specific case of financial exclusion will be analyzed—referring to the different, less populated provinces of Castilla y León (Ávila, Segovia, Soria, Zamora, and Palencia)—through the ability to access cash as an indicator, with the aim of taking appropriate measures to limit this exclusion. Within the region under study, the province of Zamora has suffered the most serious depopulation in Castilla y León so far this century. The province has lost 16% of its inhabitants since 2000. The province went from 203,000 inhabitants to barely 170,000 inhabitants. Following Zamora’s 16% drop are Palencia (−10%), León (−9%), Salamanca (−5.9%), Ávila (−4.4%) and Soria (−2.3%); Palencia, Ávila and Soria also being the subjects of study in this article [49]. Furthermore, according to [50], 76% of the municipalities of Castilla y León are in a serious or very serious demographic situation, compared to 44% of the Spanish average. Rural depopulation as a demographic and territorial phenomenon leads to demographic, economic and territorial imbalances, and serious social problems. Thus, rural depopulation has been the origin of the crisis in the countryside, which has caused the constant decrease in the weight of agriculture in the economy, and the low income derived from it [51].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Collection and Analysis

Castilla y León is one of the Spanish regions most affected by the negative impact of financial exclusion. In particular, 16% of its population (392,003 people) do not have access to a bank branch in their municipality [52]. This exclusion is even more accentuated in the provinces of Zamora, Segovia, and Avila, where more than a fifth of their inhabitants must travel outside their place of residence to access a bank branch. In these three provinces, 29%, 37% and 40% of bank branches were closed, respectively, between 2008 and 2017.

When collecting data from the sample under study, primary sources of information were used. In the case of bank branches and savings banks, the information has been extracted from their official website, selecting the bank branches and ATMs in the municipalities of the provinces of Avila, Palencia, Segovia, Soria, and Zamora. The banks and savings banks operating in these provinces under study (and therefore consulted) were: Bankia-BFA, Banco de Santander-Popular, Banco Sabadell, Bankinter, BBVA, CaixaBank, Cajamar, Caja Rural, Citibank, Deutsche Bank, Ibercaja, ING and Unicaja Banco. This, in turn, was complemented with a comparison of data from Google maps to determine if there was any duplication, and with the Bank of Spain itself and its information on branches and ATMs. With regard to post offices, the information on these has been extracted from the official website of the Spanish postal operator “Correos”. With regard to cash back and the possible points of obtaining cash via stores, information provided by the entity that currently operates this modality in Spain, ING, has been used. In this case, it has been found that the stores where cash back operates are DIA (supermarket chain), tobacconists, SHELL and GALP (gas stations), ONCE (lottery kiosks), and other small businesses. Finally, the pharmacies in each municipality of the provinces under study have been extracted from the official information provided by the respective official associations of pharmacists of Avila, Palencia, Segovia, Soria, and Zamora. All the data obtained are shown in Table A1 in the Appendix A.

Analyzing the data on bank branches, in the case of Avila, a large percentage (exactly 86% of the province) has no bank branches at all, and only 2% has 5 or more. The data for Zamora are much better, since 6% more than in the province of Avila have some branches and, with respect to municipalities with five or more, we also find 2% of them (5 municipalities in total). In this case, we find the worst data in Soria. Practically 87% of the entire province has no bank branch and 8.2% has only one, which means that there is a very low percentage of bank branches in the province. Although the data are not much better in other provinces, Palencia has 4% more municipalities with a branch, and Segovia has almost 6%. Focusing on the percentage attributed to municipalities with 4.5 or more than 5 branches, Palencia is at the top, with 3.1%, followed by Soria (2.7%), and finally, Segovia with a slightly lower figure (2.5%).

In terms of cash back points, the best data is presented by the province of Avila, with 2% more in comparison with Zamora, which has some cash back points, which is the same, 5 more municipalities have at least one more point. Soria has only 13, Segovia twice as many as Soria, and finally, Palencia is slightly above with 39 cash back points.

As far as post offices are concerned, the data are very similar in the five provinces analyzed. More than 90% of each of the municipalities do not have any post office. The data are fairly equal, although Zamora has 237 municipalities with no post office compared to 240 in Avila. Although Segovia is the province with the highest number of bank branches per surface area, it is also the province with the highest percentage of municipalities without any office (94.7%), with Palencia and Soria having very similar values (variation of only 0.2%). Analyzing these values, the fact that Segovia has the best data by surface area is due to the existence of another municipality in addition to the capital with two offices (El Espinar), while in Soria there are not two in any case, and only in the capital in Palencia.

As for ATMs, in Avila, 87.5% of the municipalities (217 out of 248) do not have any ATMs. The same happens in the case of Zamora, the data are worse than those shown above. In any case, it is still somewhat better in comparison with Ávila. In this case, 83.1% (206 municipalities) do not have access to any ATM (7 more municipalities compared to those without any bank branch). It is true that the data for both provinces are very similar (variation of 0.4%) with respect to municipalities with more than 5 ATMs. Within this percentage is the capital of both provinces, but in this case the figure for Avila is better, with 51 ATMs compared to 38 in Zamora. In Segovia, practically 82% have no ATMs at all, while 9.6% have only one. This is a limitation when it comes to obtaining cash, as it limits the citizen from belonging to a certain banking entity, or to a specific group and adapting to the conditions of that bank. Many users have several accounts, depending on the conditions required, and perhaps they cannot obtain cash at that ATM if they belong to another entity, since it would imply commissions and the customers are not willing to pay such a fee to obtain their own money. With regard to Palencia, 83.3% of this province does not have any ATM, but the figure for municipalities with only one ATM is somewhat better than in Segovia (5.8%). There are 10 municipalities with two ATMs, which increases the possibilities of deciding which bank to belong to. Lastly, in Soria, the percentage of municipalities with 3 ATMs is practically identical to that calculated for Palencia, but this does not imply that they are in the same conditions in terms of access. At this point, and having identified the difficulties that exist in some areas to access cash, a solution is proposed here to increase the rate of access to cash and thus ensure an essential part of financial inclusion and access to banking services. It is recommended to use the network of Spanish pharmacies to provide cash access points, given the wide presence of the network in the territory.

3.2. Methodology

The geographical scope of the research focuses on the provinces of Avila, Palencia, Segovia, Soria, and Zamora. These provinces are part of Castilla y León (Spain) and share the common characteristic of being provinces with low population density, as well as a very aged population. The data collected can be consulted in Table A1 of the Appendix A and also in the Data Availability Statement Section.

Index of access to cash for each municipality in the provinces under study. Based on the methodology proposed by Evans et al. [53], applied to the case of South Wales (United Kingdom), by Tischer et al. [54], applied in the city of Bristol (United Kingdom); also, by Delaney et al. and Caddy and Zhang [55,56], applied in Australia. In Europe we find its use by Matos and Aguiar [57] applied in Portugal or also in France by Banque de France [58] or recently in Austria by Stix [59] and by Chen et al., in Canada [60]. This method appears in the following equation Equation (1):

Cash access index = ∑ (bank branch × 1) + (ATM × 3) + (post office × 2) + (cash back point × 1)

Index of access to cash for each municipality, considering pharmacies and their incorporation as a point where cash can be accessed. This method developed by [45] is shown in the following equation Equation (2):

Cash access index = ∑(bank branch × 1) + (ATM × 3) + (post office × 2) + (cash back point × 1) + (pharmacy × 1)

The fact of incorporating pharmacies in the rural world and in the so called “Empty Spain” as a point of access to cash derives from the following issue: “Spain has one of the most extensive networks of pharmacies, not only in Spain, but also in Europe” [61]. Thus, the proposal to minimize the difficulties of access to cash that affect a large part of the population living in areas of low demographic density or with a certain degree of isolation (as occurs in the provinces of Avila, Palencia, Segovia, Soria, and Zamora) is to take advantage of the existing network of pharmacies as an access point to cash. In fact, in Spain, a pilot project is already being carried out in this sense in the area of Axarquia (Malaga), [62], and in the case of Correos at the pilot test level together with Banco Santander [63]. Therefore, Equation (1) has been redefined with the incorporation of a new component (pharmacy) in Equation (2). The reason for assigning a coefficient of 1 in Equation (2) to pharmacies derives (beyond what is shown in Table 1) from the fact that pharmacies have an hourly limitation. This time limitation is determined by the business hours (which are sometimes shorter in rural areas), as well as the fact that they are closed on certain days of the week (and therefore not available 24 h a day, 7 days a week).

Table 1.

Method of access to cash and score given in calculation of the Cash Access Index.

The score shown in Table 1 actually responds to a triple combination of criteria which are: 1. temporary availability, 2. universal availability, and 3. the need to perform, or not, another type of transaction when wanting to access cash. These criteria were based on those used by [53], applied to the case of South Wales (United Kingdom), by [54], applied to the city of Bristol (United Kingdom); by [55,56] in Australia and in Austria by [59] and in the case of Spain, by [45]. In terms of time availability when assigning a score, this refers to the number of hours that the item is available for use by people wishing to access the banking service. ATMs are available 24 h a day, 365 days a year, while post offices, bank branches and ATMs are subject to time restrictions that are normally determined by business hours, as well as the closure on certain days of the week (banks and post offices are not open on Sundays).

With regard to universal availability, we refer to whether the user must assume some kind of cost when accessing this service when they are not a customer of the entity offering it. In the case of ATMs, as we have already mentioned, in the Spanish banking system, customers of one bank can withdraw money at ATMs of another bank or savings bank of which they are not customers, with or without commission, provided that the entity with which they interact is part of the same payment system (e.g., EURO 6000 or Sistema 4B). However, if certain amounts are exceeded in cash withdrawals (60, 80 or 100 euros), the customer who withdraws money from a bank/savings bank of which he/she is not a customer does not bear the commission. The commission for cash withdrawals is borne by the customer’s bank/savings bank, and if it exceeds the above figures, the commission is not passed on to the customer, which means that the cash withdrawal is “free” or without commission or cost. In any case, “it is important that reasonable access to cash services be maintained for people in regional or remote locations for as long as such access is necessary”, and ATMs play a very important role in this regard [55,56]. In the case of “Correos”, the state postal service in Spain, there is no such limit [63]; since it can operate with all banking companies, and in the case of ATMs, there are limits that depend on the agreement that the company/business has with a given financial institution. In this case, the situation is similar to that of Australia; where “for many regional and remote communities, the Australia Post service is the only reasonably accessible cash deposit point” [55,56].

4. Results

Once the data analysis was carried out and the methodology described was applied, the results were obtained and are shown below. First, the results of access to cash without including pharmacies (application of Equation (1)) are shown. Subsequently, a map is shown with the results derived from including pharmacies as a point of access to cash (by application of our method, based on Equation (2)). In this way we can see the results by municipalities and provinces. Municipalities with a value of 0 are excluded, as these show that cash is not accessible in that municipality, the rest will present values equal to 1 or higher. This indicates that there is at least some point of access to cash. This allows us to detect, on the one hand, the improvement with respect to the previous situation, and, on the other hand, those rural areas where it is more difficult to access cash.

4.1. Access to Cash in the Current Situation

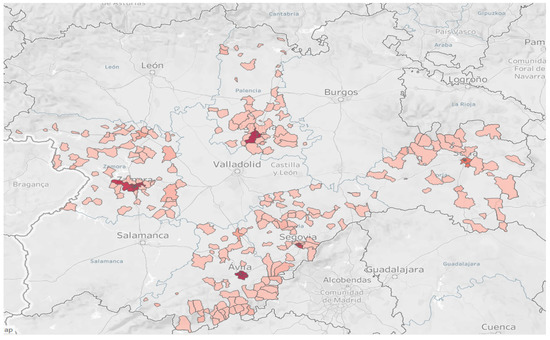

The results of access to cash without including pharmacies are shown (application of Equation (1)). The results by municipality and province are shown in Figure 1. Municipalities with a value of 0 are excluded, as these show that cash is not accessible in that municipality, the rest will present values equal to 1 or higher. This indicates that there is at least some point of access to cash. The provincial capitals (darker points shown in Figure 1) are ordered first from highest to lowest value: Palencia (221), Ávila (213), Zamora (199), Segovia (171), Soria (116). Soria is so far (year 2021), the province of Castilla y León with the greatest difficulties in obtaining cash. Much of the weight of this situation derives from the number of ATMs for each of them, since it is the value that most affects the index when multiplied by three for its calculation. These data lose a little importance if we take into account the population, since Soria is the province with the smallest population, which justifies the lower values in each of the factors analyzed: bank branches, post offices, ATMs, cash back points. At the beginning, the factor “age of the population” was mentioned because, as already mentioned, this will have a great influence due to the difficult adaptation of certain citizens to new technologies.

Figure 1.

Access to cash in the initial situation (not including pharmacy network). Source: Own elaboration based on Table 1 y Tableau Desktop Proffesional Edition.

Nowadays, these are the fundamental pillars to carry out the functions that until now have been performed in offices, with the help of specialized personnel. However, beyond the provincial capitals, where access to cash is more guaranteed; from this method and analysis we can extract and discern the difficulty to access cash that we find in several rural areas of these provinces. All this can be seen in Figure 2.

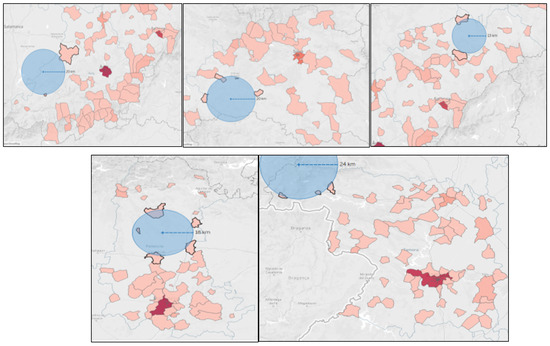

Figure 2.

Distance (km) needed to obtain cash from the furthest point in each province (current situation). Source: Own elaboration based on Tableau Desktop profesional Edition.

In the provinces of Avila and Soria (Figure 2, top left and center images), it is necessary in some cases to travel up to 20 km to reach a point where cash is available. In the case of Segovia, in some cases there are distances of up to 13 km (Figure 2, upper right image). In the case of Palencia (Figure 2, lower left image) some of its inhabitants in rural areas must travel up to 18 km to reach a municipality where they can access cash. This situation is similar to that obtained in our study for Avila and Soria. The worst case is found in Zamora (Figure 2, bottom right image), where in the northern area (bordering Galicia and Portugal), the inhabitants of these municipalities must travel up to 24 km in some cases to access a place where they can get cash. In view of this difficulty, through the results obtained with this method, we wondered how this situation of difficulty of access to cash in rural areas would improve if we incorporate pharmacies as an access point. We analyze the results in the case of providing cash in pharmacies.

4.2. Improved Access to Cash including the Pharmacy Network

Having analyzed in the previous section the percentages and number of municipalities in each of the least populated provinces of Castilla y León with or without access to cash, we will proceed to analyze the variation in the rate of access to cash by including pharmacies as a point of access.

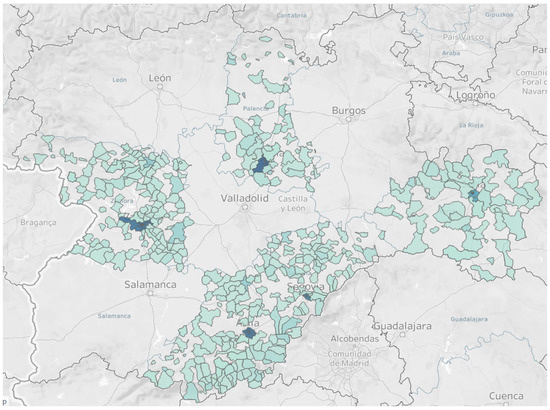

We will focus on the increase in the cash index in the provincial capitals and in the municipalities where the variation is most significant. In other words, those with a greater number of pharmacies and which therefore represent a significant improvement in access to cash. We will also later analyze spatially the reduction in several rural areas in the number of kilometers needed to access a cash point. The result shown in Figure 3 comes from applying Equation (2) again to our data, in this case, where the network of pharmacies in these provinces is included in the calculation.

Figure 3.

Access to cash in the final situation (including pharmacy network). Source: Own elaboration based on Table 1 and Tableau Desktop Proffesional Edition.

In many cases, as has already been analyzed, there are no pharmacies at all (more than half of each of the provinces), so in these municipalities this index will remain exactly the same (0); this is reflected as a blank space in the previous map. However, visually, there is a spatial improvement in terms of access to cash, given that if we compare the current figure (Figure 3) with Figure 2, the change is remarkable.

In this case, we can see that in green, many municipalities that do not have access to cash are closer than before (or now have a cash access point). In addition, in the case of pharmacies, any citizen of these municipalities who needs to buy medicines or other products, must also travel to acquire the medicines; therefore, they will take advantage of the trip to also obtain cash. The numerical results of this new situation are as follows.

In the case of the city of Avila, its index of access to cash goes from 213 to 237, being the largest of the increases analyzed. If we focus on municipalities with 3 or more pharmacies we find a notable increase in Arenas de San Pedro, Arévalo and El Tiemblo. On the other hand, the province has 156 municipalities without any pharmacy. However, there is a great improvement in access. In the case of the province of Avila, it went from 202 municipalities out of 248 (81.45%) in which it was not possible to access cash in the municipality studied; to 153 out of 248 (61.7%) municipalities where pharmacies were included as a point of access to cash. In the province of Avila, this means a reduction in the impossibility of accessing cash in 49 municipalities (19.75%).

In the case of the city of Segovia, the increase is very similar to that of Avila. While in the city of Avila there was an increase of 24 in the index, in Segovia it is 25, rising from 171 to 196, and Cantalejo, El Espinar and Torrecaballeros are among the municipalities with an increase of 3. In the case of the province of Segovia, it went from 163 out of 209 municipalities (77.9%) in which it was not possible to access cash in the municipalities studied, to 131 out of 209 (62.7%) municipalities where pharmacies were included as a point of access to cash. This means that in the province of Segovia, the impossibility of accessing cash was reduced in 32 municipalities (15.2%).

Soria had a high percentage of municipalities in the province that did not have access to cash. Focusing also on the capital, the increase in the index is much lower compared to the cities already analyzed. In the province, the municipalities of Almazán and El Burgo de Osma are more favored (looking at the increase) compared to the rest of the municipalities that make up the province of Soria, as they have 4 and 3 pharmacies, respectively. On the other hand, 42 of the 183 municipalities, increase the index in one unit, being, in some cases, the only way to obtain cash as it happened. This is a great improvement in terms of access to cash in these rural and sparsely populated areas. In the case of the province of Soria, it went from 155 out of 183 municipalities (84.7%) in which it was not possible to access cash in the municipalities studied, to 136 out of 183 (74.31%) municipalities when pharmacies were included as a point of access to cash. In the province of Soria, this means a reduction in the impossibility of accessing cash in 19 municipalities (10.38%).

In the case of Palencia, we find ourselves in the capital of the province with the greatest increase; it is an increase of 39, from 221 to 260, rising to first place in the index of access to cash among the cities analyzed. In the case of the province of Palencia, there was an increase from 154 municipalities out of 183 (84.15%) in which it was not possible to access cash among the municipalities studied, to 143 out of 183 (78.1%) municipalities when pharmacies were included as a point of access to cash. This means a reduction in the impossibility of accessing cash in 11 municipalities (6.1%) in the province of Palencia.

Finally, with regard to the province of Zamora, the fact that the capital city has 30 pharmacies leads to an increase in the index to 229, somewhat lower in comparison with the province of Avila and higher in comparison with Segovia and, of course, Soria. We also find an increase of 10 in Benavente, and 4 in Toro. The case of Benavente is much higher in comparison with the rest of the increases we have been seeing in the provinces, excluding the capital. In addition, it should be noted that the increase in one unit, in this case, affects 116 municipalities, which is equivalent to almost 47%, which have gone from not having at least one point of access to cash, to having at least one if the pharmacies are incorporated. In the case of the province of Zamora, from 188 municipalities out of 248 (75.8%) in which it was not possible to access cash in the municipalities studied, to 122 out of 248 (49.19%) municipalities where pharmacies were included as a point of access to cash. This means reducing the impossibility of accessing cash in 66 municipalities (26.6%) in the province of Zamora.

Therefore, the improvement resulting from the introduction of pharmacies as an access point to cash in these rural areas is substantial compared to the previous situation. The improvement in access to cash in the municipalities varies from 6.1% in Palencia to 26.6% in Zamora, with the improvement in access to cash from pharmacies affecting 19.75% of the municipalities in Avila, 15.2% in Segovia and 10.38% in Soria.

It can be seen that the introduction of pharmacies as a point of access to cash would be a great improvement. In all the provinces analyzed, there is a reduction in the number of kilometers that citizens in the most remote areas would have to travel in order to have access to cash. This is reflected in the previous figure (Figure 4), compared with Figure 2.

Figure 4.

Distance (km) required to obtain cash from the furthest point in each province including the pharmacy network (final location). Source: Own elaboration based on Tableau Desktop profesional Edition.

In the case of the province of Avila, citizens in the most remote rural areas would initially have to travel up to 20 km to have access to cash. However, if the network of pharmacies were incorporated to access cash, the distance would be significantly reduced to 9 km. This represents a saving of 11 km, or 55% compared to the initial situation.

As far as the province of Segovia is concerned, citizens in the most remote rural areas would initially have to travel up to 13 km in order to have access to cash. However, if the network of pharmacies were incorporated to access cash, the distance would be significantly reduced to 8 km. This represents a saving of 5 km, or 38.5% compared to the initial situation.

As far as the province of Soria is concerned, citizens in the most remote rural areas would initially have to travel up to 20 km in order to have access to cash. However, if the network of pharmacies were incorporated to access cash, the distance would be reduced to 16 km. This represents a saving of 4 km, or 20% compared to the initial situation.

As far as the province of Palencia is concerned, initially, citizens in the most remote rural areas would have to travel up to 18 km to be able to obtain cash. However, if the network of pharmacies were incorporated to access cash, the distance would be reduced to 14 km. This represents a saving of 4 km, or 22% compared to the initial situation.

As far as the province of Zamora is concerned, citizens in the most remote rural areas would initially have to travel up to 24 km in order to have access to cash. However, if the network of pharmacies were to be incorporated to access cash, the distance would be significantly reduced to 16 km. This represents a saving of 8 km, or 33% compared to the initial situation.

Therefore, the improvement resulting from the introduction of pharmacies as an access point to cash in these rural areas is substantial compared to the previous situation. The savings in kilometers needed to access cash in the municipalities varies from 20% in Soria to 55% in Avila; the improvement in access to cash by including pharmacies (by reducing the number of kilometers needed to access it) is 33% in Zamora, 38.5% in Segovia and 22% in Palencia.

5. Discussion

The closure of bank branches and ATMs of various banking entities, has a clear impact on the citizens of the most depopulated areas; especially in rural and sparsely populated areas [64]. The city of Avila has lost 10 ATMs in the last year. This effect is being accelerated in many of the provinces analyzed, due to the recent merger of Bankia and La Caixa, creating the Caixabank group. In this sense, some of its branches and ATMs will be closed in those municipalities where there is an overlap of branches. This will occur in all mergers that are carried out, thus affecting the number of branches and ATMs available. In addition, the digital business of Spanish banks has been increased (even more); for this same reason, which, once again, will lead to the closure of numerous branches. This closure will especially affect those municipalities that have several of them, or even the existence of other branches in very close municipalities.

In order to reverse the previous situation and the difficulties in accessing cash, it has been proposed in our study to incorporate pharmacies as a point of access to cash in the rural areas and in the “depopulated Spain”. Thus, the proposal to minimize the difficulties of access to cash that affect a large part of the population residing in areas of low population density or with a certain degree of isolation (as occurs in the provinces of Avila, Palencia, Segovia, Soria, and Zamora); consists of taking advantage of the existing pharmacy network as a point of access to cash.

The introduction of the pharmacy network as a cash access point is an improvement for a large number of municipalities, following some of the pilot tests already mentioned above. The one related to the Axarquia area (Malaga), (Diputation of Malaga, 2021) or in the case of Correos at pilot test level together with Banco Santander (Correos, 2021). This means eliminating the impossibility of accessing cash in 49 municipalities (19.75%) in the province of Avila, in 32 municipalities (15.2%) in the province of Segovia, in 19 municipalities (10.38%) in the province of Soria, in 11 municipalities (6.1%) in the province of Palencia and finally in 66 municipalities (26.6%) in the province of Zamora. The results obtained in the spatial analysis show that the introduction of the network of pharmacies as a point of access to cash implies a significant reduction in the distance to be traveled in the municipalities of rural areas to access cash. In the case of the province of Avila the distance would be reduced by 55%, in the province of Segovia the distance would be reduced by 38.5%, in the province of Soria the distance would be reduced by 20%, in the province of Palencia the distance would be reduced by 22% and finally in the province of Zamora the distance would be reduced by 33%.

The data are in line with previous studies conducted in other countries. Stix [59] finds in his study that 2.9% of the population of Austria (about 260,000 residents) have to travel more than 5 km to reach the nearest ATM. About 60% of these residents live in municipalities with less than 3000 inhabitants and 80% in municipalities with less than 5000 inhabitants. Municipalities with a high percentage of residents commuting more than 5 km are found in all nine Austrian provinces (except Vienna). These municipalities have an average population of 840 inhabitants. In Germany, the nearest cash withdrawal service is somewhat more difficult to access in rural regions than in cities. According to the Deutsche Bundesbank’s survey on payment behavior in Germany, the nearest cash source is on average 9.3 min away in urban areas, and 10.7 min away in rural areas [65]. In France, the situation is similar to that in Spain, as the majority (96%) of the population in these rural agglomerations, do not have ATMs and are between 5 and 15 min away from the nearest ATM [58]. As for Canada [60], it is noted that the distance and time factor fundamentally affect access to and use of cash. First, they observe that wealthy segments of the population are more likely to accept changes in distance. This suggests that wealthier individuals have a higher opportunity cost of time or are substituting cash purchases for card purchases. However, on the other hand, they find in Canada that consumers facing shorter travel distance tend to withdraw cash more frequently. Curiously, this effect is more pronounced for consumers who live less than 1.56 km from their nearest affiliated bank branch. In Australia, the study [55] shows that while an estimated 99% of the population has a cash withdrawal point within 15 km (and a cash deposit location within 17 km), the remaining 1% (about 250,000 people); have to travel more than 15 km to the nearest cash access point. Moreover, in Australia, [56] indicates that in June 2020, 95% of the Australian population lived within 4.3 km of a cash withdrawal point and within 5.5 km of a cash deposit point. These average distances barely changed compared to 2017, despite the fact that the total number of cash access points in Australia decreased considerably during this period. However, some cities have more precarious access to cash, with few nearby alternative access points.

In some rural areas outside Europe such as Ghana, ref. [66] have conducted a study on the potential improvement of financial inclusion through the use of mobile money. However, they have found that “the suitability of mobile money for financial inclusion in rural areas has a mixed picture. This is because, although the platform ensures ease, proximity and speed of transactions, digital illiteracy, irregular service delivery and poor network connectivity cast doubt on the suitability of mobile money for the rural environment”; leaving access to cash as a guarantor of financial inclusion. Moreover, [67] points out in their study for the case of Tunisia, that physical barrier (in this case the distance needed to access a bank or an ATM) is configured as a fundamental barrier to ensure financial inclusion. In the case of China, [68,69] have found in their study how financial inclusion can be improved through digital transformation, the level of development of the area and the culture and training of its citizens. According to [70], regions with higher income countries tend to have better digital financial inclusion. However, digital technology has helped several low-income countries to improve their financial inclusion. However, this improvement does not extend to other low-income countries in the region. Therefore, for rural areas where incomes are lower and associated with lower education, this solution may not work and therefore, access to traditional banking services remains as a guarantor of financial inclusion.

In the case of Spain, [64] report that 249,407 inhabitants (2.7% of the Spanish population) do not have access to a bank branch. These municipalities are generally small and located in unpopulated areas. The regions with the highest number of municipalities without a branch are Castilla y León, Castilla-la Mancha, Catalonia, and Aragón. In [58], the authors report that more than 80% of the municipalities in this area (Ávila) have difficulties in accessing financial services.

Although the incorporation of the pharmacy network as a point of access to cash can partially alleviate the situation, as we have shown, other measures should be necessary. For example, the promotion of bank-office buses [64]; which tour the provinces offering banking services and which have not been included in our study, this being a limiting factor in the results obtained. The use of these mobile banking offices by bus may be a clear limitation to our study, as their possible impact has not been considered. Another limitation of the study, which is shared with the other studies carried out and analyzed in the literature review, methodology and discussion of the results, is that it is an analysis of the current situation. This will change over time, especially if we consider the continuous process of bank mergers that has been taking place in Spain for some time. This is causing a gradual reduction in the number of ATMs and bank branches to avoid duplication between merging entities. Looking to the future, this study could evolve in two different directions. On the one hand, a questionnaire survey of citizens living in depopulated areas could be carried out to find out whether this solution is to their liking (since they will ultimately be the ones who will use the service). On the other hand, to carry out a research questionnaire to the owners of pharmacies to check whether they would be willing to participate in the implementation of this measure.

However, other solutions based on technology can help to reverse this situation in rural areas. Many central banks are considering the implementation of a CBDC (central bank digital currency) [70,71]. However, their feasibility and acceptance should first be analyzed [72,73]. In the case of one of the provinces under analysis (Avila), as shown in the study by [45], its acceptance would be high, so it could be another possible solution for improving financial inclusion.

6. Conclusions

As has been shown, the incorporation of pharmacies as cash dispensing points in the province of Avila means that 37% of municipalities (92 of them) have access to cash, compared with 12.5% if we focus on ATMs, or 10.9% on cash back points. Even better data are found in the province of Segovia, where only 64% (134 municipalities) could not have access to cash through pharmacies, although it is true that the percentage of ATMs and bank branches is also higher than in the province of Avila. As far as Zamora is concerned, it was mentioned above that it is at the top of the improvement with this incorporation, since 50% of the municipalities have at least one pharmacy. This is excellent data evidence to promote cash despite the bank restructurings that are being generated, and the bad data that we found in the calculation of the index. Approximately only 13% of the municipalities had access to an ATM or bank branch, and 11% to cash back points. Finally, although Soria is the province with the lowest rate of access to cash, the incorporation of pharmacies as cash dispensers is very similar to what occurs in the province of Palencia. Only 25% of the municipalities (45 in Soria and 46 in Palencia) would benefit from this incorporation. Overall, taking the five Castilian and Leon provinces analyzed, the inclusion of pharmacies for this purpose has a positive impact. We can affirm that this would be a very useful measure if the objective is to continue to promote cash, and in some cases to facilitate procedures for those inhabitants who are not very skilled in the use of new technologies.

As previously mentioned, the cash back points will be developed and the number of establishments (gas stations, supermarkets, stores, etc.) will be increased over time, as has been the case up to now. In addition, as indicated at the beginning of the article, the idea is to promote financial inclusion in order to achieve economic growth, especially in depopulated rural areas. This measure would clearly enhance financial inclusion through greater access to cash and a shorter distance to travel to access it.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.L.N.A.; data curation, E.A.D., and S.L.N.A.; formal analysis, S.L.N.A., E.A.D. and J.J.-V.; funding acquisition, R.F.R.F.; investigation, S.L.N.A., E.A.D. and J.J.-V.; methodology, S.L.N.A.; project administration, S.L.N.A., J.J.-V. and R.F.R.F.; resources, R.F.R.F.; software, S.L.N.A., J.J.-V. and R.F.R.F.; supervision, J.J.-V.; visualization, J.J.-V. and E.A.D.; writing—original draft, S.L.N.A. and R.F.R.F.; writing—review and editing, J.J.-V. and R.F.R.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by AAUCAV, grant number BI2021 and the APC was partially funded by the incentive granted to the authors by the Catholic University of Ávila.

Data Availability Statement

The following are available online at https://bit.ly/31wnshJ.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Tableu Inc. for allowing us to use Tableau Desktop Professional Edition for scientific purposes.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Bank branches, ATMs, cashback points, post offices and pharmacies by province and municipality.

Table A1.

Bank branches, ATMs, cashback points, post offices and pharmacies by province and municipality.

| Province | No. of Bank Branches | No. of Municipalities with Bank Branches | % of Municipalities with Bank Branches | No. of ATMs | No. of Municipalities with ATM | % of Municipalities with ATM | No. of Cashback Points | No. of Municipalities with cashback points | % of Municipalities with Cashback | No. of Post Offices | No. of Municipalities with Post Offices | % of Municipalities with Post Offices | No. of Phar-Macies | % of Municipalities with Pharmacies | No. of Municipalities with Pharmacies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ávila | 0 | 214 | 86.3 | 0 ATM | 217 | 87.5 | 0 points | 221 | 89.1 | 0 | 240 | 96.8 | 0 | 156 | 62.9 |

| 1 | 17 | 6.9 | 1 ATM | 13 | 5.2 | 1 points | 19 | 7.7 | ≥1 | 8 | 3.2 | 1 | 83 | 33.5 | |

| 2 | 3 | 1.2 | 2 ATM | 4 | 1.6 | 2 points | 4 | 1.6 | 2 | 5 | 2.0 | ||||

| 3 | 5 | 2.0 | 3 ATM | 4 | 1.6 | 3 points | 1 | 0.4 | ≥3 | 4 | 1.6 | ||||

| 4 | 6 | 2.4 | 4 ATM | 3 | 1.2 | 4 points | 0 | 0.0 | |||||||

| 5 | 3 | 1.2 | 5 ATM | 3 | 1.2 | 5 points | 0 | 0.0 | |||||||

| >5 | 2 | 0.8 | > 5 ATM | 4 | 1.6 | > 5 points | 2 | 0.8 | |||||||

| Palencia | 0 | 159 | 83.2 | 0 ATM | 160 | 83.8 | 0 points | 177 | 92.7 | 0 | 178 | 93.2 | 0 | 145 | 75.9 |

| 1 | 14 | 7.3 | 1 ATM | 11 | 5.8 | 1 points | 6 | 3.1 | ≥1 | 13 | 6.8 | 1 | 38 | 19.9 | |

| 2 | 6 | 3.1 | 2 ATM | 10 | 5.2 | 2 points | 4 | 2.1 | 2 | 4 | 2.1 | ||||

| 3 | 6 | 3,1 | 3 ATM | 2 | 1.0 | 3 points | 0 | 0.0 | ≥3 | 4 | 2.1 | ||||

| 4 | 2 | 1.0 | 4 ATM | 4 | 2.1 | 4 points | 1 | 0.5 | |||||||

| 5 | 1 | 0.5 | 5 ATM | 1 | 0.5 | 5 points | 2 | 1.0 | |||||||

| >5 | 3 | 1.6 | > 5 ATM | 3 | 1.6 | > 5 points | 1 | 0.5 | |||||||

| Segovia | 0 | 170 | 81.3 | 0 ATM | 171 | 81.8 | 0 points | 189 | 90.4 | 0 | 198 | 94.7 | 0 | 134 | 64.11 |

| 1 | 24 | 11.5 | 1 ATM | 20 | 9.6 | 1 points | 13 | 6.2 | ≥1 | 11 | 5.3 | 1 | 67 | 32.06 | |

| 2 | 5 | 2.4 | 2 ATM | 7 | 3.3 | 2 points | 3 | 1.4 | 2 | 4 | 1.91 | ||||

| 3 | 6 | 2,9 | 3 ATM | 5 | 2.4 | 3 points | 0 | 0.0 | ≥3 | 4 | 1.91 | ||||

| 4 | 2 | 1.0 | 4 ATM | 2 | 1.0 | 4 points | 3 | 1.4 | |||||||

| 5 | 1 | 0.5 | 5 ATM | 1 | 0.5 | 5 points | 0 | 0.0 | |||||||

| >5 | 2 | 1.0 | > 5 ATM | 3 | 1.4 | > 5 points | 1 | 0.5 | |||||||

| Soria | 0 | 159 | 86.9 | 0 ATM | 171 | 81.8 | 0 points | 189 | 90.4 | 0 | 198 | 94.7 | 0 | 134 | 64.1 |

| 1 | 15 | 8.2 | 1 ATM | 20 | 9.6 | 1 points | 13 | 6.2 | ≥1 | 11 | 5.3 | 1 | 67 | 32.1 | |

| 2 | 2 | 1.1 | 2 ATM | 7 | 3.3 | 2 points | 3 | 1.4 | 2 | 4 | 1.9 | ||||

| 3 | 2 | 1,1 | 3 ATM | 5 | 2.4 | 3 points | 0 | 0.0 | ≥3 | 4 | 1.9 | ||||

| 4 | 3 | 1.6 | 4 ATM | 2 | 1.0 | 4 points | 3 | 1.4 | |||||||

| 5 | 0 | 0.0 | 5 ATM | 1 | 0.5 | 5 points | 0 | 0.0 | |||||||

| >5 | 2 | 1.1 | > 5 ATM | 3 | 1.4 | > 5 points | 1 | 0.5 | |||||||

| Zamora | 0 | 199 | 80.2 | 0 ATM | 206 | 83.1 | 0 points | 226 | 91.1 | 0 | 237 | 95.6 | 0 | 128 | 51.6 |

| 1 | 36 | 14.5 | 1 ATM | 19 | 7.7 | 1 points | 19 | 7.7 | ≥1 | 11 | 4.4 | 1 | 116 | 46.7 | |

| 2 | 3 | 1.2 | 2 ATM | 16 | 6.5 | 2 points | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 1 | 0.4 | ||||

| 3 | 3 | 1.2 | 3 ATM | 2 | 0.8 | 3 points | 0 | 0.0 | ≥3 | 3 | 1.2 | ||||

| 4 | 2 | 0.8 | 4 ATM | 0 | 0.0 | 4 points | 1 | 0.4 | |||||||

| 5 | 2 | 0,8 | 5 ATM | 2 | 0.8 | 5 points | 0 | 0.0 | |||||||

| >5 | 3 | 1.2 | > 5 ATM | 3 | 1.2 | > 5 points | 2 | 0.8 | |||||||

Source: Own elaboración based on Bankia-BFA, Banco de Santander-Popular, Banco Sabadell, Bankinter, BBVA, CaixaBank, Cajamar and Caja Rural, Citibank, Deutsche Bank, Ibercaja, ING, Unicaja Banco, Google maps, Bank of Spain, and official college of pharmacists of Ávila, Palencia, Segovia, Soria, and Zamora.

References

- The World Bank. Global Findex Database. Global Findex. Available online: https://globalfindex.worldbank.org/ (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- Koku, P.S. Financial exclusion of the poor: A literature review. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2015, 33, 654–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyshon, A.; Thrift, N. Geographies of Financial Exclusion: Financial Abandonment in Britain and the United States. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 1995, 20, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbó, S.; Gardener, E.P.M.; Molyneux, P. Financial Exclusion in the UK. In Financial Exclusion; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2005; pp. 14–44. [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair, S. Financial Exclusion: An Introductory Survey. 2013. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/7086629/Financial_Exclusion_An_Introductory_Survey (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Amidžic, G.; Massara, M.; Mialou, A. Assessing Countries’ Financial Inclusion Standing: A New Composite Index. 2014; Volume 14. Available online: https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2014/wp1436.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Park, C.-Y.; Mercado, R.J. Financial Inclusion, Poverty, and Income Inequality in Developing Asia. SSRN Electron. J. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Henry, N.; Pollard, J.; Sissons, P.; Ferreira, J.; Coombes, M. Banking on exclusion: Data disclosure and geographies of UK personal lending markets. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Sp. 2017, 49, 2046–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Caplan, M.A.; Birkenmaier, J.; Bae, J. Financial exclusion in OECD countries: A scoping review*. Int. J. Soc. Welf. 2021, 30, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World Bank Financial Inclusion. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/financialinclusion/overview#1 (accessed on 26 September 2021).

- The World Bank How to Measure Financial Inclusion. World Bank. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/financialinclusion/brief/how-to-measure-financial-inclusion (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- International Monetary Fund. Financial Access Survey 2020. IMF Data. Available online: https://data.imf.org/?sk=E5DCAB7E-A5CA-4892-A6EA-598B5463A34C (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Mylonidis, N.; Chletsos, M.; Barbagianni, V. Financial exclusion in the USA: Looking beyond demographics. J. Financ. Stab. 2019, 40, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sain, M.R.M.; Rahman, M.M.; Khanam, R. Financial Exclusion and the Role of Islamic Finance in Australia: A Case Study in Queensland. Australas. Account. Bus. Financ. J. 2018, 12, 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nowacka, A.; Szewczyk-Jarocka, M.; Zawiślińska, I. Socio-demographic determinants of financial exclusion of the unemployed on the local labour market: A case study. Ekon. i Prawo 2021, 20, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramley, G.; Besemer, K. Poverty and Social Exclusion in the UK: Vol. 2: The Dimensions of Disadvantage; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2017; ISBN 9781447334224. [Google Scholar]

- Iwanicz-Drozdowska, M.; BBBdowski, P. Financial Services Provision and Prevention of Financial Exclusion in Poland: National Survey. SSRN Electron. J. 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arner, D.W.; Buckley, R.P.; Zetzsche, D.A.; Veidt, R. Sustainability, FinTech and Financial Inclusion. Eur. Bus. Organ. Law Rev. 2020, 21, 7–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danisman, G.O.; Tarazi, A. Financial Inclusion and Bank Stability: Evidence from Europe. SSRN Electron. J. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavón Cuéllar, L.I. International financial inclusion: Some multidimensional determinants. Small Bus. Int. Rev. 2018, 2, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, I.; Karakuş, R.; Yildiz, M. Spatial Determinants of Financial Inclusion over Time. J. Int. Dev. 2018, 30, 1474–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedline, T.; Naraharisetti, S.; Weaver, A. Digital Redlining: Poor Rural Communities’ Access to Fintech and Implications for Financial Inclusion. J. Poverty 2020, 24, 517–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempson, E.; Whyley, C. Kept Out or Opted Out? Understanding and Combating Financial Exclusion; University Bristol Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 1999; p. 56. [Google Scholar]

- Nieri, L. Access to Credit: The Difficulties of Households. In New Frontiers in Banking Services; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 107–140. [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair, S. Financial inclusion and social financialisation: Britain in a European context. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2013, 33, 658–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roa, M.J.; Carvallo, O.A. Inclusión Financiera y el costo del uso de Instrumentos Financieros Formales: Las Experiencias de América Latina y el Caribe. 2018. Available online: https://publications.iadb.org/es/inclusion-financiera-y-el-costo-del-uso-de-instrumentos-financieros-formales-las-experiencias-de (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Devlin, J.F. A Detailed Study of Financial Exclusion in the UK. J. Consum. Policy 2005, 28, 75–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J.F. An analysis of influences on total financial exclusion. Serv. Ind. J. 2009, 29, 1021–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, S. Perspective of Technology in Achieving Financial Inclusion in Rural India. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2014, 11, 472–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chu, A.B. Mobile Technology and Financial Inclusion. In Handbook of Blockchain, Digital Finance, and Inclusion; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 1, pp. 131–144. [Google Scholar]

- Cull, R.; Demirguc-Kunt, A.; Morduch, J. Banking the World: Empirical Foundations of Financial Inclusion; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.-C.; Wang, C.-W.; Ho, S.-J. Financial inclusion, financial innovation, and firms’ sales growth. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2020, 66, 189–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchis Palacio, J.R.; Padilla Sánchez, A.M. La relación causa-efecto entre exclusión/inclusión social y financiera. Una aproximación teórica. REVESCO. Rev. Estud. Coop. 2021, 138, e69168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, W.A. Theory of Economic Growth; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, A.; Duflo, E.; Glennerster, R.; Kinnan, C. The Miracle of Microfinance? Evidence from a Randomized Evaluation. Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 2015, 7, 22–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Karlan, D.S.; Zinman, J. Expanding Microenterprise Credit Access: Using Randomized Supply Decisions to Estimate the Impacts in Manila. SSRN Electron. J. 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Attanasio, O.; Augsburg, B.; De Haas, R.; Fitzsimons, E.; Harmgart, H. Group Lending or Individual Lending? Evidence from a Randomized Field Experiment in Rural Mongolia. SSRN Electron. J. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelucci, M.; Karlan, D.; Zinman, J.; Fishbane, A.; Hillis, A.; Safran, E.; Strohm, R.; Torres, B.; Troychansky, A.; Velez, I.; et al. Win Some Lose Some? Evidence from a Randomized Microcredit Program Placement Experiment by Compartamos Banco Thanks to Tim Conley for Collaboration and Mapping Expertise. Thanks to Innovations for Poverty Action Staff, including Win Some Lose Some? Eviden. 2013. Available online: https://www.nber.org/papers/w19119 (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Argent, N.M.; Rolley, F. Financial Exclusion in Rural and Remote New South Wales, Australia: A Geography of Bank Branch Rationalisation, 1981–1998. Aust. Geogr. Stud. 2000, 38, 182–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, J.A.; Molina, J.; Rodríguez, M. Financial accessibility in branchless municipalities: An analysis for Andalusia. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2021, 29, 883–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.S.T.; Berggren, B. The Effect of Bank Branch Closures on New Firm Formation: The Swedish Case; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; Volume 65, ISBN 0123456789. [Google Scholar]

- Alessandrini, P.; Presbitero, A.F.; Zazzaro, A. Banks, distances and firms financing constraints. Rev. Financ. 2009, 13, 261–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppock, S. The everyday geographies of financialisation: Impacts, subjects and alternatives. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2013, 6, 479–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panigyrakis, G.G.; Theodoridis, P.K.; Veloutsou, C.A. All customers are not treated equally: Financial exclusion in isolated Greek islands. J. Financ. Serv. Mark. 2002, 7, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Náñez Alonso, S.L.; Jorge-Vazquez, J.; Reier Forradellas, R.F. Detection of financial inclusion vulnerable rural areas through an access to cash index: Solutions based on the pharmacy network and a CBDC. Evidence based on Ávila (Spain). Sustainability 2020, 12, 7480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorge-Vázquez, J.; Chivite-Cebolla, M.P.; Salinas-Ramos, F. The Digitalization of the European Agri-Food Cooperative Sector. Determining Factors to Embrace Information and Communication Technologies. Agriculture 2021, 11, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorge-Vázquez, J.; Reier-Forradellas, R.F.; Náñez-Alonso, S.L.; Sáez-Herráez, I. La digitalización de los servicios bancarios y su incidencia en el medio rural. In Advances in Education, ICT and Innovation: Issues for Business and Social Enhancing; Dykinson: Madrid, Spain, 2021; pp. 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Náñez Alonso, S.L.; Jorge-Vázquez, J.; Reier-Forradellas, R.F. Adopción de una moneda digital (CBDC) para prevenir la exclusión financiera en el medio rural. In Advances in Education, ICT and Innovation: Issues for Business and Social Enhancing; Dykinson: Madrid, Spain, 2021; pp. 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Bank of Spain. La Distribución Espacial de la Población en España y sus Implicaciones Económicas; Bank of Spain: Madrid, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Southern Sparsely Populated Areas (SSPA) Documents-Mapa 174. Zoning of Spanish Municipalities Subject to Serious and Permanent Demographic Disadvantages. Available online: https://sspa-network.eu/en/documentation/ (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Álvarez Llorente, T.; Sousa Soares de Oliveira Braga, J.; Barros Cardoso, A. Social Problems in Southern Europe. A comparative Assessment. In Social Problems in Southern Europe. A Comparative Assessment; Entrena-Durán, F., Soriano-Miras, R.M., Duque-Calvache, R., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham/Camberley, UK, 2020; pp. 143–156. [Google Scholar]

- IVIE La Población sin Acceso a una Sucursal Bancaria en su Municipio Aumenta un 34% desde 2008—Web Ivie. Available online: https://www.ivie.es/es_ES/la-poblacion-sin-acceso-una-sucursal-bancaria-municipio-aumenta-34-desde-2008/ (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Evans, J.C.N.; Tischer, D.; Davies, S.V. Geographies of Access to Cash—Identifying Vulnerable Communities in a Case Study of South Wales. 2020. Available online: https://research-information.bris.ac.uk/en/publications/geographies-of-access-to-cash-identifying-vulnerable-communities- (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Tischer, D.; Evans, J.; Davies, S. Mapping the Availability of Cash—A Case Study of Bristol’s Financial Infrastructure; University of Bristol: Bristol, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Delaney, L.; Hara, A.O.; Finlay, R. Cash Withdrawal Symptoms. 2019. Available online: https://www.econbiz.de/Record/cash-withdrawal-symptoms-delaney-luc/10012270379 (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Caddy, J.; Zhang, Z. How Far Do Australians Need to Travel to Access Cash? Reserve Bank of Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2021; pp. 10–17. [Google Scholar]

- de Matos, J.C.; D’Aguiar, L. Assessing Financial Inclusion in Portugal from the Central Bank’s Perspective 1 Assessing Financial Inclusion in Portugal from the Central Bank ’ S Perspective. 2017. Available online: https://www.bis.org/ifc/publ/ifcb47a.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Banque de France Report on Public Access to Cash in Metropolitan France. 2019. Available online: https://www.banque-france.fr/sites/default/files/media/2020/12/02/560ta19_rapport_-_acces_au_public_aux_especes_en_france_metropolitaine_-_23072019_clean.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Stix, H. A spatial analysis of access to ATMs in Austria. Monet. Policy Econ. 2020, 39–59. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/a/onb/oenbmp/y2020iq3-20b3.html (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Chen, H.; Strathearn, M.; Voia, M. Consumer Cash Withdrawal Behaviour: Branch Networks and Online Financial Innovation. 2021. Available online: https://www.bankofcanada.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/swp2021-28.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Consulting, C. España Cuenta con la red de Farmacias más Grande de Europa. Available online: https://www.actasanitaria.com/espana-cuenta-con-la-red-de-farmacias-comunitarias-mas-grande-de-europa/ (accessed on 3 June 2021).

- Diputación de Málaga Comienza un Proyecto Piloto para sacar Dinero en las Farmacias de Pueblos sin Cajeros Automáticos ni bancos—Presidencia—Diputación de Málaga. Available online: https://www.malaga.es/presidencia/575/com1_md3_cd-42654/comienza-un-proyecto-piloto-para-sacar-dinero-en-las-farmacias-de-pueblos-sin-cajeros-automaticos-ni-bancos (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Correos Las Oficinas de Correos de toda España ya Prestan los Servicios de Ingreso y Retirada de Efectivo para los Clientes del Banco Santander—Correos. Available online: https://www.correos.com/sala-prensa/las-oficinas-de-correos-de-toda-espana-ya-prestan-los-servicios-de-ingreso-y-retirada-de-efectivo-para-los-clientes-del-banco-santander/# (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Jiménez Gonzalo, C.; Tejero Sala, H. Bank Branch Closure and Cash access in Spain. Financ. Stab. Rev. 2018, 34, 35–56. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsche Bundesbank Monthly Report: Cash Withdrawals and Payments in Urban and Rural Areas. 2020; Volume 72. Available online: https://www.bundesbank.de/resource/blob/835308/883b0d7e02a4d9edbebb4069038fbebf/mL/2020-06-stadt-land-vergleich-data.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Serbeh, R.; Adjei, P.O.-W.; Forkuor, D. Financial inclusion of rural households in the mobile money era: Insights from Ghana. Dev. Pract. 2021, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amari, M.; Anis, J. Exploring the impact of socio-demographic characteristics on financial inclusion: Empirical evidence from Tunisia. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2021, 48, 1331–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Li, Z. Does Digital Financial Inclusion Affect Agricultural Eco-Efficiency? A Case Study on China. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Hueng, C.J.; Hu, W. Measurement and spillover effect of digital financial inclusion: A cross-country analysis. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2021, 28, 1738–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Náñez Alonso, S.L.; Echarte Fernández, M.Á.; Sanz Bas, D.; Kaczmarek, J. Reasons Fostering or Discouraging the Implementation of Central Bank-Backed Digital Currency: A Review. Economies 2020, 8, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Náñez Alonso, S.L.; Jorge-Vazquez, J.; Reier Forradellas, R.F. Central Banks Digital Currency: Detection of Optimal Countries for the Implementation of a CBDC and the Implication for Payment Industry Open Innovation. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G. Why is China going to issue CBDC (Central Bank Digital Currency)? J. Internet Electron. Commer. Res. 2020, 20, 161–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solberg Söilen, K.; Benhayoun, L. Household acceptance of central bank digital currency: The role of institutional trust. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).