Abstract

Regional governments and regional intergovernmental organizations play an increasingly important role in land use and transportation planning in many countries. In the U.S., regional organizations such as metropolitan planning organizations provide regional forums and institutions to coordinate actions of local government necessary to overcome collective action problems that result from the fragmentation of local authority. Their regional scope allows them to directly address collaboration problems or broker collaborative arrangements among local governments within their boundaries. Nevertheless, the scale of regional problems often extends beyond the boundaries of these regional entities. Thus, collaboration across regional governance organizations is necessary to address problems that have multi-regional impacts, such as large transportation projects. Extant research generally measures regional collaboration based on counts of collaboration actions undertaken, but this does not account for the fact that some are symbolic, while others require resources and commitment. Drawing insights from the institutional collective action framework, we advance an explanation for how regional organizations overcome collaboration risks to participate in collaborative solutions to regional and multi-regional problems. The analysis employs a unique national survey of metropolitan planning organizations (MPOs) and adds a novel application of item response theory (IRT) to capture differences in risk or difficulty among collaborative actions. The IRT results offer support for our ICA-based explanation of collaboration commitments. The implications of the findings for theory development and empirical study of RIGOs are discussed in conclusion.

1. Introduction

Metropolitan regions provide an increasingly important policy venue, not just in transportation but also in land use and sustainability decisions. Metropolitan-level action has been called for as necessary to govern the fragmented system of local governments found in urban regions [1,2,3,4]. Regional intergovernmental organizations (RIGOs) are by definition the largest intergovernmental, multipurpose cross-boundary organization in a region [5,6,7]. Their geographic scope allows them to directly address these problems or to broker collaborative arrangements among local governments within their boundaries. Metropolitan planning organizations (MPO) have primary responsibility for transportation infrastructure in the U.S. and allocate intergovernmental transit funding. Many MPOs function as the RIGO, but others operate within a larger region. What has escaped attention is the fact that urban problems, and the scale of collective action for problems, often extend beyond the boundaries of MPOs either because they do not encompass entire urbanized areas or the problems span multiple regions. For example, urban sprawl, infrastructure congestion, and pollution impact expansive regions and thus exceed the scale of any single MPO [5]. Thus, collaboration among these regional organizations is necessary to address multi-regional policy impacts.

Regional governance and collaborative management have received much attention in the urban planning and urban politics literature, yet collaborations among regional organizations receive almost no attention [1,6]. In the US, collaborations among MPOs are common in practice, but we know little about the process and scope of collaborations, the risks associated with collaborative mechanisms, or how these risks are affected by whether an MPO is a stand-alone organization or one part of a larger RIGO. Although some conceptual frameworks such as institutional collective action (ICA) account for regional spillovers across multiple governments and authorities, most empirical studies based on ICA limit their attention to relationships within limited geography, typically a single region.

MPOs are not only central players in urban transportation and economic development; they also play an increasingly important role in climate adaption and mitigation [8,9]. The U.S. transportation sector barely trails the electric power industry in its greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions [8,10], yet transportation has received considerably less attention in climate policy research. MPOs channel the demands of diverse local constituencies into long-term plans and short-term funded project lists that shape a region’s transportation infrastructure. MPOs’ efforts to integrate climate change considerations into transportation planning have received some research attention [10,11,12,13]. The mission of MPOs is regional, but limitations in the geographic scope of their authority mean that collaboration with other MPOs is necessary to fulfill that mission and address regional and multi-regional problems [14].

The study of local collaboration emphasizes how the nature of collective problems shapes the extent to which cities collaborate with various other actors [10,15,16,17,18]. Extant research generally measures regional collaboration based on counts of collaboration actions undertaken. The procedure of counting each collaboration equally masks the fact that some actions may be mostly symbolic [19], while other actions require strong administrative, fiscal, or political commitment or require behavior change on the part of the participants [20,21,22]. This limitation is particularly salient for research based on the ICA framework since it focuses on collaboration risks. Not adequately accounting for the fact that some collaborations are more difficult to undertake might lead to faulty conclusions regarding the factors that influence effective collaboration.

This manuscript begins to fill this lacuna by investigating the extent to which MPOs collaborate with each other and in what ways. We explain how fragmented authority and collaboration risks related to problems, actors, and institutions influence the latent collaboration commitments of MPOs. After discussing collective actions dilemmas from divided responsibility among multiple MPOs. We extend the ICA framework to explain how regional organizations overcome collaboration risks to craft collaborative solutions to regional and multi-regional problems. Applying the ICA framework to MPOs, we advance hypotheses for how collaboration risk influences the propensity of MPOs to collaborate. We measure commitment to collaboration by applying item response theory (IRT). The estimated models provide support for the ICA-based explanation of collaboration commitments and point to limitations of research based on additive indices of policy or collaboration instruments.

1.1. Conceptual Framework

MPOs were established through the U.S. Federal Aid Highway Act of 1973 and tasked with regional planning activities for transportation. MPOs hold responsibility for transportation planning and implementation with the authority to allocate federal and state transportation funds [23]. Although public goods pose collective-action challenges at all levels of government [24,25], they are particularly troublesome for local governments because their jurisdictional reach is smaller, so spillovers and incentives to freeride are greater [24]. Expanding literature focuses on city-level actions in collaboration with other cities and actors to address transportation dilemmas and transportation-related issues of energy sustainability, etc., within the boundaries of their defined region [17,25]. MPOs boundaries were defined in the 1970s and often did not encompass the contemporary urbanized region as it has developed over recent decades as the reach and connectedness of urbanized areas has expanded beyond the boundaries of the geographic and political lines of the individual MPOs [26,27,28]. Kim [29] illustrates this with the example of southeast Florida, where the boundaries of regional organizations often do not match the scale of the problems their plans are intended to address since the urbanized area spans three individual MPOs. The three MPOs have engaged in interregional collaboration through several mechanisms to create a council to coordinate on specific transportation projects [30,31,32,33].

1.2. ICA Framework

Fragmentation of policy and political authority across urban regions produces inefficiencies in land use, infrastructure, and mobility [25,34,35,36]. ICA dilemmas occur between independent governments as the consequences of one unit’s actions spilling over to another’s jurisdiction, such as when one government or regional organization in a metropolitan area makes a policy decision that affects neighboring regions. ICA dilemmas make integrated solutions to complex problems difficult. The ICA theoretical framework [36,37] systematically compares alternative mechanisms to mitigate these problems. MPOs are one such mechanism [38,39]. One focus of the ICA approach is to identify factors that influence the choice of mechanisms for collaboration among local authorities [18,36].

Collaboration is risky because even an arrangement that promises to benefit all participants can fail if it is difficult to set up, it proves difficult to agree on a fair distribution of costs and benefits, or it is in the interest of one or more participants to exit or freeride. The literature defines these barriers to collaboration as coordination, division, and defection problems [22,36,37]. The ICA framework argues that collaboration risk is defined by three factors: the nature of the collective problem, the composition and decision making of the affected actors, and the existing institutions in place.

1.2.1. The Nature of the Problem

Collaboration risk is connected to the nature of the ICA dilemmas itself [18,40]. The specific characteristics of the underlying ICA dilemma may determine how responsibility is divided or fragmented is salient [41,42]. Fragmented authority in terms of the number of individual government units included in the boundaries of the MPO and the extent to which an MPO is part of a larger urbanized area that extends beyond its boundaries make collaborations more difficult. The nature of urban service problems is linked to the distribution of population and urban form [41,43].

1.2.2. Actor Characteristics

MPOs will have differing incentives to engage in collective action depending on their organizational structure and decision-making processes. Conflicting goals among participants present a difficult collective action dilemma [15,44]. Collaboration risks are higher for ICA dilemmas involving goal conflicts, not just because actors need to agree on the division of benefits and costs but also because of potential defection from the agreement [40,43]. Where there is less conflict over goals, the problem is simply one of coordination on how to reach joint goals. Social, demographic characteristics such as race and income have been found to influence the likelihood of successful collaboration [25,42]. Collaborations may fail to materialize because potential partners have incentives to freeride on the efforts of others based on goal divergence [37,40,43]. For MPOs, the representativeness of the governing board, the proportion of elected officials versus administrators on the board, whether the MPO is freestanding or part of a regional council of governments, and resource capacity are key characteristics [7,45].

1.2.3. Existing Institutions

State-level rules and arrangements can be important in shaping MPO collaboration and mitigating collaboration risk [3]. State government transportation policy can shape and constrain collaborative behaviors [3,30,45,46]. Additionally, state associations of MPOs might facilitate collaborations [6,47,48]. “Regional models of cooperation,” as the U.S. Department of Transportation addresses it, allows an MPO to develop multi-jurisdictional transportation plans and agreements to improve regional transportation and air pollution beyond the agency boundaries, reducing interruptions to essential coordination of solutions [33]. Multiple examples of these coordinated interregional collaborations between transportation entities have arisen throughout the United States with relative success in formalizing agreements and handling smooth coordination to address a multiplicity of issues including rail, urban, rural, travel demand modeling, and air quality [32,33,49].

Statewide associations in a minority of states have formed over time and integration within urbanized regions [3,41]. These associations connect MPOs within the specified state; however, they lack formal authority and so supplement and inform rather than direct regional efforts, creating a forum for information and ideas, fostering cooperation between national/state/local entities, and promoting the development of a coordinated planning process [31,50].

2. Materials and Methods

Data on MPO interregional collaboration activity were obtained through a national survey of MPOs. Independent variables to capture collaboration risk were extracted from the U.S. Census Bureau and Bureau of Transportation Statistics National Transportation Atlas Database and the Integrated City Sustainability Database [51]. The MPO survey was conducted by the Center for Urban Transportation Research and reported in the U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration “Staffing and Administrative Capacity of Metropolitan Planning Organizations” [52]. The survey was sent to MPO directors in 396 of the 409 MPOs operating in the United States. A total of 279 MPOs participated in the survey, with a 70 percent response rate. Included in the survey were questions asking respondents to identify mechanisms employed for collaboration with other MPOs, including joint planning, joint purchasing, MOUs or interlocal agreements, joint public events, a joint long-range transportation plan (LRTP), joint regional transportation plan, and planning linkage activities. The organizational and institutional factors are derived from the LGR MPOs database, which compiles the institutional structure and decision-making arrangements of every U.S. MPO and links it to city and MPO surveys.

2.1. Item Response Methodology

We seek to measure MPOs’ commitment to collaboration addressing ICA dilemmas, but an organization’s willingness to collaborate is a latent trait. We address this using an item response theory (IRT) to estimate each MPOs commitment to collaboration. Extant research has generally attempted to measure these latent commitments through additive indices of collaborative mechanisms used, with higher scores indicating greater collaboration. The additive indices constructed from dichotomous items that are predominant in the investigation of ICA collaborations [3,18,53,54,55] can be problematic because they assume all actions involve similar commitments [2].

While factor analysis is appropriate for continuous variables, IRT can be used for dichotomous (e.g., “pass/fail” or “yes/no”) survey items. IRT models rely on Item Characteristic Curves (ICCs) to estimate the probability a given respondent will answer a survey question correctly, accounting for both their own latent ability and the parameters of the question itself (usually its difficulty and discrimination). Examining MPO collaboration choices in this manner allows us to estimate an MPOs latent level of collaborative commitment based on its own resources, capacities, and interests and the differentially weighted collaboration instruments. While some collaborative actions are a low commitment or symbolic, others require strong administrative, fiscal, or political commitment or require behavior change on the part of local governments and their residents. MPOs vary widely in their ability to take meaningful action: they differ in their responsibilities over local government functions, they often are constrained by their positions in labor and housing markets, and they have unequal resources [56].

Item response theory (IRT) models offer an alternative to weight each item differentially within an index construction, adjusting for the reality that some policy tools are easier or lower-cost commitments and adopted far more frequently than others. IRT has been used to measure attitudes or beliefs [57], the ideology of legislators [58], and the transparency levels of national governments [59]. IRT has also been applied to scale the difficulty of policy actions related to law enforcement [60], sustainability [61], economic development [62], and collaborative networking [63]

IRT models thus estimate the relationship between an unobservable ability or trait measured by the instrument and the item response, which is whether or not a regional organization has adopted a given collaboration mechanism [64]. Two-parameter IRT models can be used to distinguish between respondents by estimating a parameter for the difficulty of the item and a second parameter for how well each policy tool discriminates between two otherwise similarly performing respondents. Here, the probability an MPO uses a particular tool is determined by its difficulty. In a two-parameter model, the discrimination parameter is an estimate of how well the item (collaboration action) differentiates between two organizations that may have adopted a similar count (but different) bundle of collaborative tools. The discrimination parameter estimates the ability of a tool to differentiate between two organizations’ collaboration commitments. As applied in this analysis, a high discrimination value estimate is visualized as a larger slope and means the probability of using the tool increases as a city’s latent commitment increases. Thus, IRT models are probabilistic methods that allow for greater differentiation between MPOs with varying levels of the latent commitment to collaboration. Our two-parameter IRT model is specified as

where the probability that a sustainable policy item or tool i is adopted by a city depends upon policymakers collective latent commitment θs, the difficulty of adopting the item βi, and how well the item discriminates between respondent cities αi. Theoretically, policy tools that require greater commitment (whether it be higher costs, political risk-taking, etc.) have a greater weighting relative to other tools.

We obtain estimates of these latent commitment levels with an IRT model weighting activities based on the estimated difficulty and discrimination parameters. Our outcome measure is an additive collaboration index including nine survey items capturing collaborative actions: joint planning tasks; joint data purchasing, interlocal agreement/MOU; joint public involvement activities; joint MTP/LRTP; development of regional transportation plan; planning and environmental linkages activities, joint congestion management process, joint air quality planning activities. We can assess the value added by the IRT approach by examining the estimates of the difficulty and discrimination parameters. If the parameter estimates differ significantly across all items, the IRT approach is more appropriate than merely summing the frequency of items. To compare IRT to additive indices, we constructed an index of collaborative actions MPOs could engage in. We find significant variance among scales.

The index of regional collaboration difficulty demonstrated a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.797, suggesting the items had internal consistency as a reliable scale. In keeping with the ICA framework, the probability of successful collaboration is a function collaborative commitment of an MPO and the characteristics of the type of collaboration. A second issue with additive indices is how well they differentiate between two cities that may reach the same count of collaborative instruments via different combinations of mechanisms. Discrimination and difficulty scores for all items were statistically distinguishable from 0. Table 1 displays the frequency of adoption for each collaboration mechanism.

Table 1.

MPO use of specific collaboration mechanism.

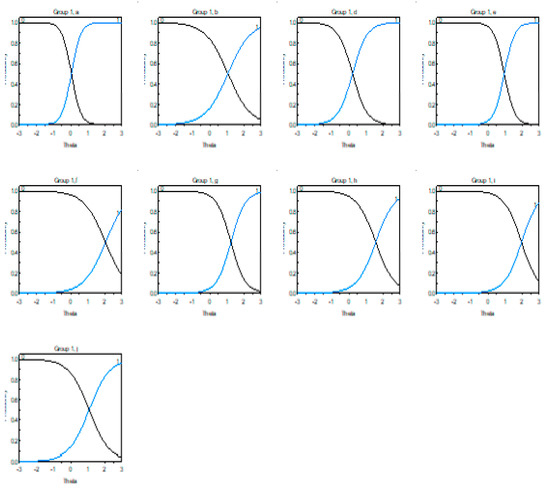

Figure 1 displays the item characteristic curves (ICC) for each item. An ICC presents each item’s uniqueness in terms of difficulty and discrimination. The ICC describes the probability that an MPO “succeeds” in adopting a particular collaborative action. Figure 1 shows that every curve is different by reflecting each item’s characteristics. In particular, the curve for the development of a regional plan (item f) indicates it is the most difficult item since the actual curse is located between 0 and 3 and the right-end point just reaches 0.8. Joint air quality planning (item i) is the next most difficult one. Figure 1 also demonstrates that joint planning activities (item a) best discriminates respondents’ ability since the slope is most steep. The curve for joint MTP/LRPT (item e) shows a similar tendency. Table 2 report item response discrimination and difficulty scores.

Figure 1.

Item characteristic curves.

Table 2.

Item response scores.

2.2. Explanatory Measures

To measure collaboration risk linked to the nature of the problem, potential externalities of fragmented authority are captured in the number of general-purpose governments in each MPO and whether an MPO is part of a consolidated metropolitan statistical area (CMSA). We also include population, population density to capture potential scale economies.

The MPO actor characteristics examined here include median household income, percent of the population white for the MSA, and percentage of MPO governing board members that are local elected officials as opposed to administrators. Actor capacity is measured by the number of MPO full-time staff, the MPO governing board size, and whether an MPO is freestanding or linked to a RIGO, as reported in the database. The state-level institution variables measure whether there are state statutes addressing MPO coordination and whether there is an active state-level MPO association. Summary statistics and sources are presented for these independent variables are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary statistics.

3. Results

Table 4 reports the results of simple OLS regressions of the transaction risk. We estimate the measure difficulty of regional collaboration derived from the IRT analysis. We cluster standard errors by state. These results offer support for the ICA-based hypothesis. We find the elements of each of the collaboration risks identified in the ICA framework are related to MPOs undertaking high-commitment regional collaborative actions. All of the statistically significant effects are in the predicted directions.

Table 4.

Regression for regional collaboration action difficulty.

In examining the nature of the ICA dilemmas that regional organizations face, the number of local governments stands out as significant. This is consistent with the framework’s emphasis on the fragmentation of governmental authority. The effect of an MPO being located in a large urbanized area as indicated by a CMSA did not achieve significance. Population and density were unrelated to the regional collaboration efforts of MPOs.

Several MPO characteristics predict a high commitment to regional collaboration, including income levels and scope of representation on the governing board as measured by the number of voting members. The strongest statistical support is from state−level institutions that reduce barriers to institutional collective action. State transportation statutes that direct or guide the coordination of MPOs enhanced their ability to engage in high difficulty regional collaboration actions. The presence of a statewide association on MPOs was also found to influence engagement in collaborations.

We next compare these regression results with the estimates generated for the same model using an additive index based on the nine collaborative actions. Table 5 compares the coefficients estimated by each model. The results report several striking deviations in the findings based on the measure of collaboration. Population density was not linked to the collaborations requiring greater effort or commitment, but here it is related to the additive collaboration instrument index. Location in a CSA and the scope of representation on their governing board as measured by the number of voting members was a predictor of high difficulty collaboration. Finally, the proportion of elected officials on the governing body is significantly related to the simple additive collaboration index. This is consistent with the finding of Mullins et al. [10] that representation of elected officials leads to symbolic policy actions.

Table 5.

Comparison of additive index and IRT difficulty score regression estimates.

4. Discussion

The empirical results have implications for both theory and methods. The findings reported here offer new evidence supporting the robustness of the ICA framework to explain intergovernmental organization collaborations and suggest that the ICA framework is applicable to collaborations across, not just within regions. The findings also advance the methods of collaboration research by demonstrating that IRT scaling produces results that differ in meaningful ways from those using conventional additive measures of collaborative actions.

The results support the extension of the ICA framework to a regional level to understand the collaboration risk barriers that MPO must overcome to effectively addressing ICA dilemmas in land use and transportation. The results reinforce conclusions that the extent of local governmental fragmentation is the key characteristic of the problem that influences the ability to engage in more difficult high-commitment collaborations. The ICA framework posits that collaboration risks that pose barriers to collaboration arise from: (1) the nature of the problem, (2) the characteristics of the participants, and (3) existing institutions. We review the findings for each of these categories of variables and compare them with finding from extant research.

Intergovernmental spillover effects appear to be more important than economies of scale in influencing collaborative commitments. Collaboration risk is connected to the nature of the ICA dilemmas. The characteristics of the underlying ICA dilemma may determine how responsibility is divided or fragmented is salient [18,41,42]. The fragmentation of authority [65,66] that defines ICA dilemmas is measured by the number of member governments within the MPO. Within regions, fragmentation is generally one of the greatest barriers to collaboration [36]. At the interregional level, fragmentation also impedes collaboration, but for a different reason. Where MPOs have a large number of member local governments, internal decision making is more costly and time-consuming. High internal decision-making costs both distract attention from external issues and makes the MPO a less valuable collaboration partner [1,36,38].

MPOs will have differing incentives to engage in collective action depending on their organizational structure and decision-making processes. Several MPO characteristics predict a high commitment to regional collaboration, such as income levels and scope of representation on the governing board as measured by the number of voting members. Income levels and the scope of MPO representation were linked to collaboration. These results mirror the findings that fiscal capacity and local institutions for representation strongly impact intergovernmental collaborations within regions [2,14,40,42,43,44].

State-level rules and arrangements can be important in shaping MPO collaboration and mitigating collaboration risk [3]. State-level institutions, such as supportive state legislation and associations of RIGOs, enabled MPOs to take on more difficult collaboration actions. The strongest statistical support is from state-level institutions that reduce barriers to institutional collective action. State transportation statutes that direct or guide the coordination of MPOs enhanced collaboration commitment. Again, previous work has focused on intraregional collaborations [67], but the results reported here extend those finding to the regional scale.

Applying IRT, we are able to better capture differences among the types of regional collaborative activities MPOs participate in. Some activities do not require MPOs to give up autonomy and involve little commitment of resources. MOUs and many joint planning tasks or projects or often constitute low commitment collaboration actions. On the other hand, collaboration on the core functions of long-range transportation planning has the potential to address regional scale ICA dilemmas but involve sacrificing some control and require commitments of core resources. For this reason, an additive index summing collaborative actions together may not be adequate to distinguish high and low commitment regional collaboration.

The findings demonstrate how item response theory models can offer an alternative scaling to weight each item differentially within an index construction to measure the underlying latent construct. From this analysis, we construct a measure of the commitment or difficulty for regional collaboration actions. The application of IRT here produces findings that are generally consistent with those reported in psychology [57], political science [58], public administration [59], criminology [60], sustainability [61], and economic development [62]. The utility of combining the ICA theory conception of collaboration risk and IRT scaling is strongly supported by Table 5’s comparison of regression estimates for the IRT model and one using an additive index. The application of IRT is particularly salient in this setting because collaboration risks are difficult to overcome and pose a key barrier to collaboration within the institutional collective action framework.

The findings have implications beyond the U.S., as urban problems transcend governments boundaries in many countries. The ICA framework has been applied to investigate interlocal collaboration in a number of countries, including Portugal [68], China [69], Canada [70], Switzerland [71], Brazil, and Mexico [72]. For the most part, this research has focused on collaborations within regions rather than across regions. One exception is China, where several studies of pollution control and economic development have addressed cross-regional collaboration [69]. The results of these studies are generally consistent with those presented here.

The results also have methodological implications. We are limited in our ability to generalize beyond MPOs, but the results suggest finding regarding collaboration based on additive indices need to be re-examined in light of the differences reported here. This is particularly important at the city level, where the conventional wisdom is built on studies using additive indices. The IRT approach applied here to collaboration can also be applied to policy commitment [73].

Future research should not only reassess the findings of previous investigations of intraregional collaboration through the application of IRT scaling but also investigate individual collaborations. This study provides an ego-centric analysis of factors influencing MPOs’ latent commitment to collaboration. Case studies and dyadic network analysis can enrich our understanding of how collaboration risk barriers to collaboration can be overcome by considering both partners’ perceptions of risk. Such work can fortify our understanding of collaboration risk and commitment in addressing land use sustainability and transportation issues that impact multiple jurisdictions. Finally, based on the similarities and differences between intraregional and interregional collaboration reported here, future research could develop and test multilevel models of land-related collaboration within and across regions simultaneously.

5. Conclusions

The geographic scale of collective action for governing problems such as urban sprawl, infrastructure, congestion, GHG, and air pollution often exceeds the boundaries and reach of a single MPO and affects an entire urbanized region. In response, MPOs have engaged in an array of collaborative activities. Collaboration among MPOs is not uncommon, but it has escaped the vision of intergovernmental scholars. We explore the prevalence and types of regional collaborative activities MPOs participate in. We argue that low-collaboration risk activities do not require MPOs to give up autonomy and involve little commitment of resources. MOUs and many joint planning tasks or projects or often constitute low commitment collaboration actions. On the other hand, a regional collaboration that impacts the core functions of long-range transportation planning requires sacrificing some control and requires commitments of resources. Thus an additive index summing collaborative actions together is inadequate to distinguish high and low commitment regional collaboration.

We address this problem with though an application of item response theory to assess the collaboration commitments of MPOs. IRT models offer an alternative to weighing each item differentially within an index construction to measure the underlying latent construct. From this analysis, we construct a measure difficulty for regional collaboration actions. We draw on the institutional collective action framework to generate predictions of the influence of collaboration risks on the difficulty of colligations undertaken.

The empirical results have implications for theory and methods. The results support the extension of the ICA framework to a regional level to understand the barriers to collaboration that MPO overcome in addressing ICA dilemmas. The results reinforce conclusions that the level of governmental fragmentation is a key characteristic of the problem that influences the ability to engage in more difficult high-commitment collaborations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.C.F. and S.K.; methodology, S.K.; writing—original draft preparation, R.C.F.; writing—review and editing, S.K.; modeling, W.-J.K. visualization, S.K.; funding acquisition, S.K. All authors contributed equally. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Seoul National University of Science and Technology Research Program, award number 2019-0890.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Archived through Local Governance Research, Local Governance Lab, and the Sustainable Healthy Cities Network https://www.sustainablehealthycities.org/data-sets/ (Accessed 12 December 2019).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Gerber, E.; Henry, A.; Lubell, M. Political Homophily and Collaboration in Regional Planning Networks. Am. J. Political Sci. 2013, 57, 598–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Deslatte, A.; Feiock, R.C.; Wassel, K. Urban Pressures and Innovations: Sustainability Commitment in the Face of Fragmentation and Inequality. Rev. Policy Res. 2017, 34, 700–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, J. State-Level Influences on Community-Level Municipal Sustainable Energy Policies. Urban Aff. Rev. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliano, G. The changing landscape of transportation decision making. Transp. Res. Record. 2007, 2036, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matlock, M.; Fricker, J. Multi-Jurisdictional Issues Related to Congestion Management; Purdue University Press: West Lafayette, IN, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, D.; Nelles, J.; Dougherty, G.; Rickabaugh, J. Discovering American Regionalism: An Introduction to Regional Intergovernmental Organizations; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.; Nelles, J. Order out oi chaos: The case for a new conceptualization of the cross-boundary instruments of American regionalism. Urban Aff. Rev. 2020, 56, 325–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, S.; Fragkias, M. Metropolitan planning organizations and climate change action. Urban Climate. 2018, 25, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleviss, D.L. Transportation is critical to reducing greenhouse gas emissions in the United States. WIREs Energy Environ. 2021, 10, e390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullin, M.; Feiock, R.; Niemeier, D. Climate Planning and Implementation in Metropolitan Transportation Goverance. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbour, E.; Deakin, E.A. Smart growth planning for climate protection: Evaluating California′s Senate Bill 375. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2012, 78, 70–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juhola, S.; Westerhoff, L. Challenges of adaptation to climate change across multiple scales: A case study of network governance in two European countries. Environ. Sci. Policy 2011, 14, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemeier, D.; Grattet, R.; Beamish, T. “Blueprinting” and climate change: Regional governance and civic participation in land use and transportation planning. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2015, 33, 1600–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youm, J.; Feiock, R. Interlocal Collaboration and Local Climate Protection. Local Gov. Stud. 2019, 45, 777–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y. From competition to collaboration: Intergovernmental economic development policy networks. Local Gov. Stud. 2016, 42, 171–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benton, J. Local government collaboration: Considerations, issues, and prospects. State Local Gov. Rev. 2013, 45, 220–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, O.; Pierre, J. Exploring the strategic region: Rationality, context, and institutional collective action. Urban Aff. Rev. 2010, 46, 218–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youm, J.; Terman, J. Dynamic Collaboration: The Effects of External Rules and Collaboration Scope on Interlocal Collaboration. Rev. Policy Res. 2020, 37, 823–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, E.B.; Dorothy, D.M.; Lynch, M. Understanding Local Adoption and Implementation of Climate Change Mitigation Policy. Urban Aff. Rev. 2011, 47, 433–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaswami, A. Building Environmentally Sustainable, Healthy and Climate Resilient Cities using a Social-Ecological-Infrastructure Systems Framework. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 26, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Amundsen, H.; Berglund, F.; Westskog, H. Overcoming Barriers to Climate Change Adaptation—A Question of Multilevel Governance? Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2010, 28, 276–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, J.; Hawkins, C. The costs of cooperation: What the research tells us about managing the risks of service collaborations in the U.S. State Local Gov. Rev. 2013, 224–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciara, G.-C. Metropolitan Transportation Planning: Lessons from the Past, Institutions for the Future. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2017, 83, 262–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, M. The Logic of Collective Action; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Okitasari, M.; Kidokoro, T. Planning beyond boundaries: Perspectives on the Challenging Intergovernmental Collaboration Towards a Sustainable Regional Governance in Indonesia. In Proceedings of the 49th ISOCARP Congress 49th Annual Meeting, Brisbane, Australia, 2 October 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, J.F.; Farquhar, M.B. Assessing Progress: The State of Metropolitan Planning Organizations under ISTEA and TEA-21. Int. J. Public Adm. 2005, 28, 1057–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innes, J.E.; Booher, D.E.; Vittorio, S.D. Strategies for Megaregion Governance Collaborative Dialogue, Networks, and Self Organization. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2011, 77, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S. Elevating the Scale of Cross-Boundary Collaboration Inter-Regional Collaboration Mechanisms; Urban Affairs Review Forum: Chicago, IL, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Goetz, A.; Dempsey, P.; Larson, C. Metropolitan planning organizations: Findings and recommendations for improving transportation planning. Publius J. Fed. 2002, 32, 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, J. Review of MPO Long Range Transportation Plans and Regional MPO Panning Activities and Products; Department of Transportation: Tampa, FL, USA, 2005.

- Seggerman, K.E.; Kramer, J. Regional MPO Alliances in Florida: A Model for Setting Megaregion Transportation Policies? Center for Urban Transportation Research: Tampa, FL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Southeast Florida Transportation Council. About. Retrieved from Southeast Florida Transportation Council. 2018. Available online: https://www.seftc.org/about (accessed on 26 August 2021).

- Kwon, S.; Park, S. Metropolitan governance: How regional organizations influence interlocal land use coordination. J. Urban Aff. 2014, 36, 925–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Chen, T.; Yi, H.; Xu, X.; Chen, S.; Chen, W. Collaborative Environmental Governance, Inter-Agency Cooperation and Local Water Sustainability in China. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Feiock, R.C. The institutional collective action framework. Policy Stud. J. 2013, 41, 397–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Transportation. Regional Models of Cooperation. Retrieved 2019, from Center for Accelerating Innovation. 2016. Available online: https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/innovation/everydaycounts/edc-3/regional.cfm (accessed on 26 August 2021).

- Feiock, R.C.; Scholz, J.T. Self-Organizing Federalism: Collaborative Mechanisms to Mitigate Institutional Collective Action Dilemmas; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Swann, W.; Kim, S. Practical prescriptions for governing fragmented governments. Policy Politics 2018, 46, 273–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terman, J.; Feiock, R.; Youm, J. When Collaboration is Risky Business: The Influence of Collaboration Risks on Formal and Informal Collaboration. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2019, 50, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S. Regional Governance Institutions and Interlocal Cooperation for Service Delivery; Working Group on Interlocal Service Cooperation, Wayne State University: Detroit, MI, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Song, M.; Jung, K.; Ki, N.; Feiock, R. Testing structural and relational embeddedness in collaboration risk. Ration. Soc. 2020, 32, 67–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, K. Sources of organizational resilience for sustainable communities: An institutional collective action perspective. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, Y.; Lee, I. A longitudinal network analysis of intergovernmental collaboration for local economic development. Urban Aff. Rev. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.; Feiock, R.; Bae, J. The roles of regional organizations for interlocal resource exchange: Complement or substitute? Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2014, 44, 339–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschken, H. Scale, the Silo Effect and Intergovernmental Cooperation: Institutional Analysis of Global Cities and Ecological Sustainability. In Proceedings of the Political Science Association 2013 Annual Meeting, Chicago, IL, USA, 29 August–1 September 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo, M. Beyond institutional collective action: Why and when do metropolitan governments collaborate? State Local Gov. Rev. 2019, 51, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickabaugh, J. Regionalism with and without metropolitanism: Governance structures of rural and non-rural regional intergovernmental organizations. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2021, 51, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, L.; Ray, R.; King, D. Who decides? Toward a typology of transit governance. Urban Sci. 2021, 5, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association of Metropolitan Planning Organizations. Statewide MPO Associations. Retrieved from Association of Metropolitan Planning Organizations. 2014. Available online: http://www.ampo.org/about-us/statewide-mpo-associations/ (accessed on 26 August 2021).

- Feiock, R.; Krause, R.; Hawkins, C.; Curely, C. The Integrated City Sustainability Database. Urban Aff. Rev. 2014, 50, 577–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bond, A.; Kramer, J.; Seggerman, K. Staffing and Administrative Capacity of Metropolitan Planning Organizations; US Department of Transportation: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. Available online: https://www.planning.dot.gov/documents/Staffing_Administrative_Capacity_MPOs.pdf/ (accessed on 26 August 2021).

- Hawkins, C. Competition and Cooperation: Local Government Joint Ventures for Economic Development. J. Urban Aff. 2010, 32, 253–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, J.; LeRoux, K.; Shrestha, M. Institutional Ties, Transaction Costs, and External Service Production. Urban Aff. Rev. 2009, 44, 403–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M. Testing the forms and consequences of collaboration risk in emergency management networks. Soc. Sci. J. 2020, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, C.V.; Krause, R.M.; Feiock, R.C.; Curley, C. Making Meaningful Commitments: Accounting for Variation in Cities’ Investment of Staff and Fiscal Resources to Sustainability. Urban Stud. 2016, 53, 1902–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMars, C. Item Response Theory; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Clinton, J.; Jackman, S.; Rivers, D. The statistical analysis of roll call data. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 2004, 98, 355–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hollyer, J.R.; Rosendorff, B.P.; Vreeland, J.R. Measuring Transparency. Political Anal. 2014, 22, 413–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osgood, D.; McMorris, B.; Potenza, M. Analyzing multiple-item measures of crime and deviance: Item response theory scaling. J. Quant. Criminol. 2020, 18, 267–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deslatte, A.; Swann, W.L. Context matters: A Bayesian analysis of how organizational environments shape the strategic management of sustainable development. Public Admin. 2017, 95, 807–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deslatte, A.; Stokan, E. Sustainability Synergies or Silos? The Opportunity Costs of Local Government Organizational Capabilities. Public Admin. Rev. 2020, 80, 1024–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Robinson, S.E.; Torenvlied, R. A Bayesian approach to measurement bias in networking studies. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2015, 45, 542–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, D.A.; Bakker, R.; Carroll, R.; Hare, C.; Poole, K.T.; Rosenthal, H. Analyzing Spatial Models of Choice and Judgment with R; CRC Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, D.; Johnson, B.; Stokan, E.; Overton, M. Institutional collective action during COVID-19: Lessons in local economic development. Public Admin. Rev. 2020, 80, 862–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauroth, N. Conflict on the Red River: Applying the institutional collective action framework to regional flood policy. Public Policy Adm. 2018, 33, 311–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, E.; Loh, C. Spatial dynamics of vertical and horizontal intergovernmental collaboration. J. Urban Aff. 2015, 37, 270–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Camões, P.; Tavares, A.; Teles, F. Assessing the intensity of cooperation: A study of joint delegation of municipal functions to inter-municipal associations. Local Gov. Stud. 2021, 47, 593–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, J.; Yi, K.; Wen, J. Under what conditions do governments collaborate? A qualitative comparative analysis of air pollution control in China. Public Manag. Rev. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Suo, L.; Ma, J. A network approach to interprovincial agreements: A study of Pan Pearl River Delta in China. State Local Gov. Rev. 2015, 47, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spicer, Z. Regionalism, municipal organization, and interlocal cooperation in Canada. Can. Public Policy. 2015, 41, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meza, O.; Grin, E.; Fernandes, A.; Abrucio, F. Intermunicipal Cooperation in Metropolitan Regions in Brazil and Mexico: Does Federalism Matter? Urban Aff. Rev. 2019, 55, 887–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deslatte, A.; Stokan, E. Hierarchies of Need in Sustainable Development: A Resource Dependence Approach for Local Governance. Urban Aff. Rev. 2014, 55, 1125–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).