The Small Property Rights Housing Institution in Mainland China: The Perspective of Substitutability of Institutional Functions

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- (1)

- What is the level of credibility achieved by SPRH?

- (2)

- Is the institutional credibility of SPRH related to the substitutability of its functions?

- (3)

- Do any other factors affect the credibility of SPRH?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Credibility Thesis

2.2. The Institutional Environment for Housing in Urban China

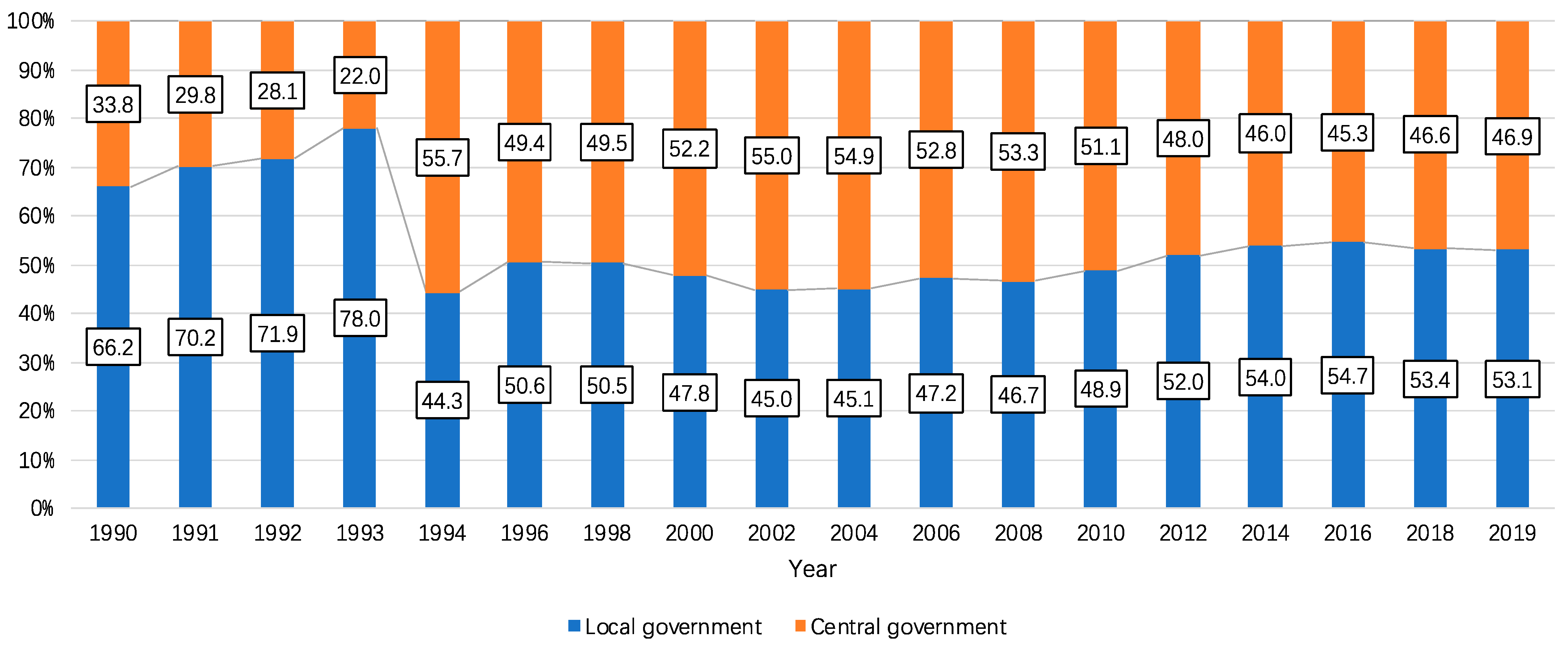

3. Materials and Methods

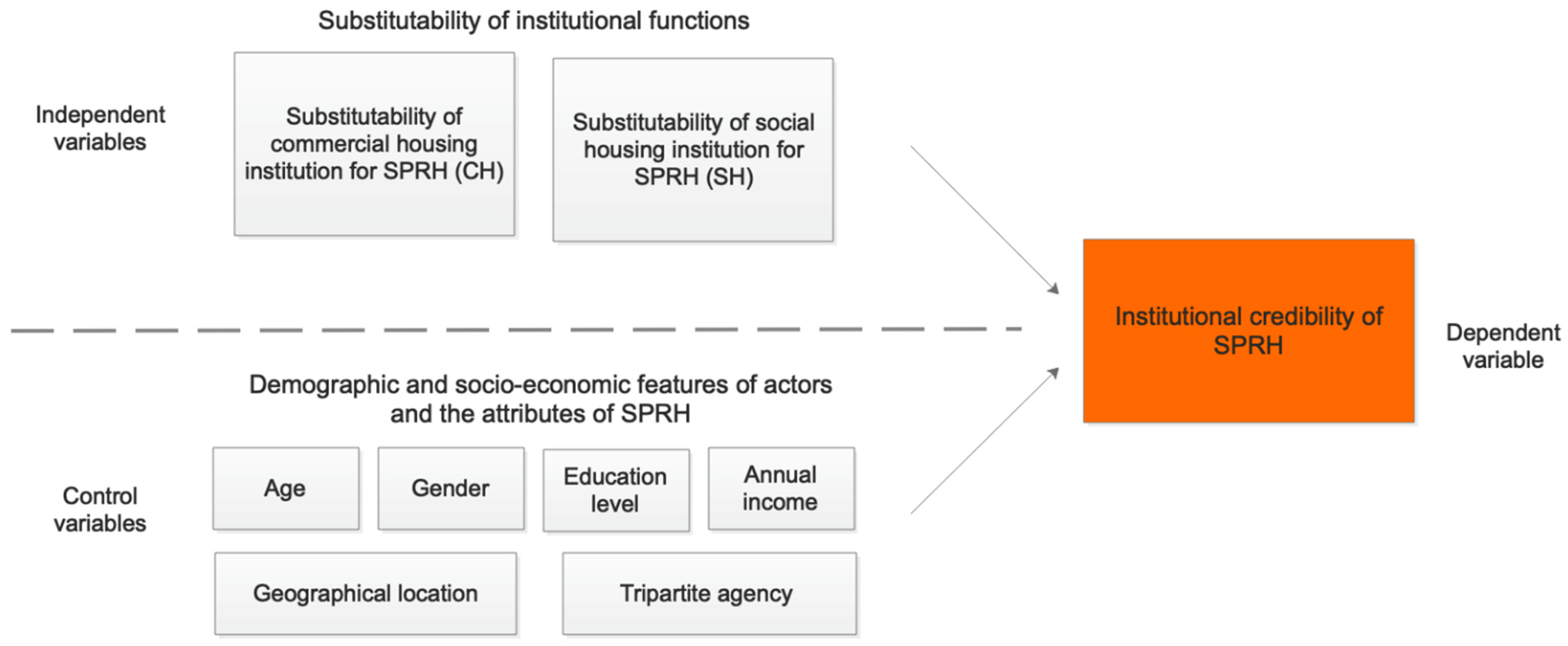

3.1. Analytic Framework

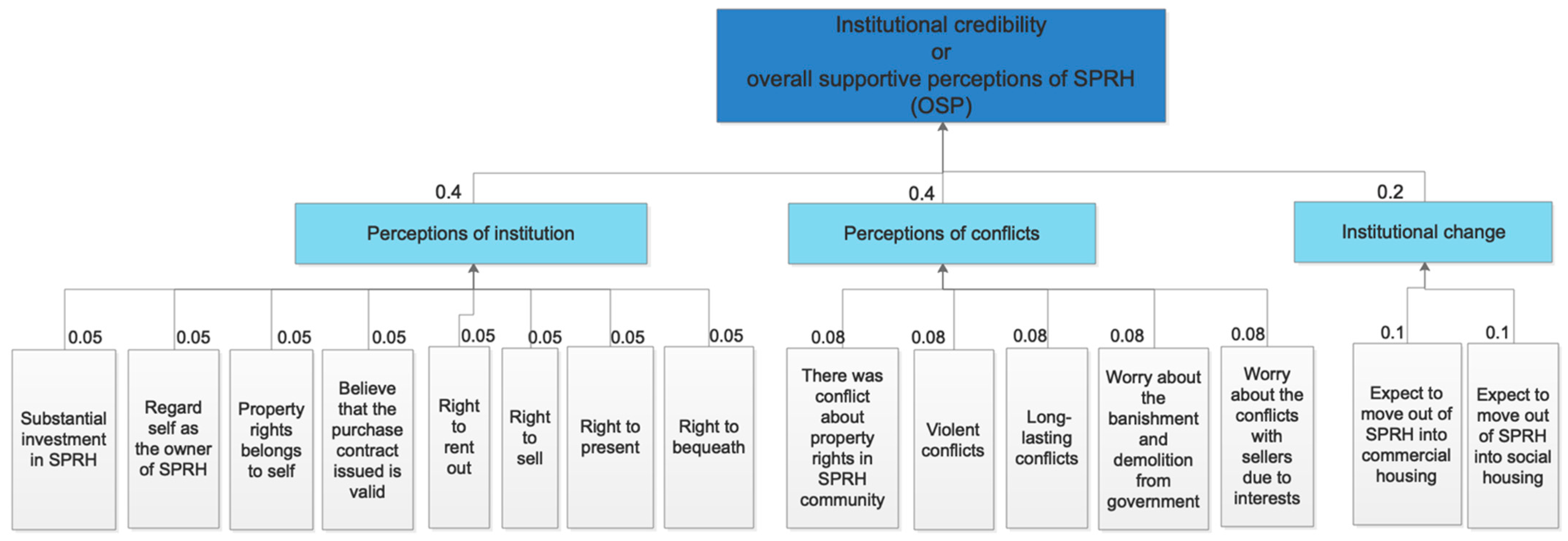

3.2. Measurements of the Variables

3.3. Collection of Data

4. Results

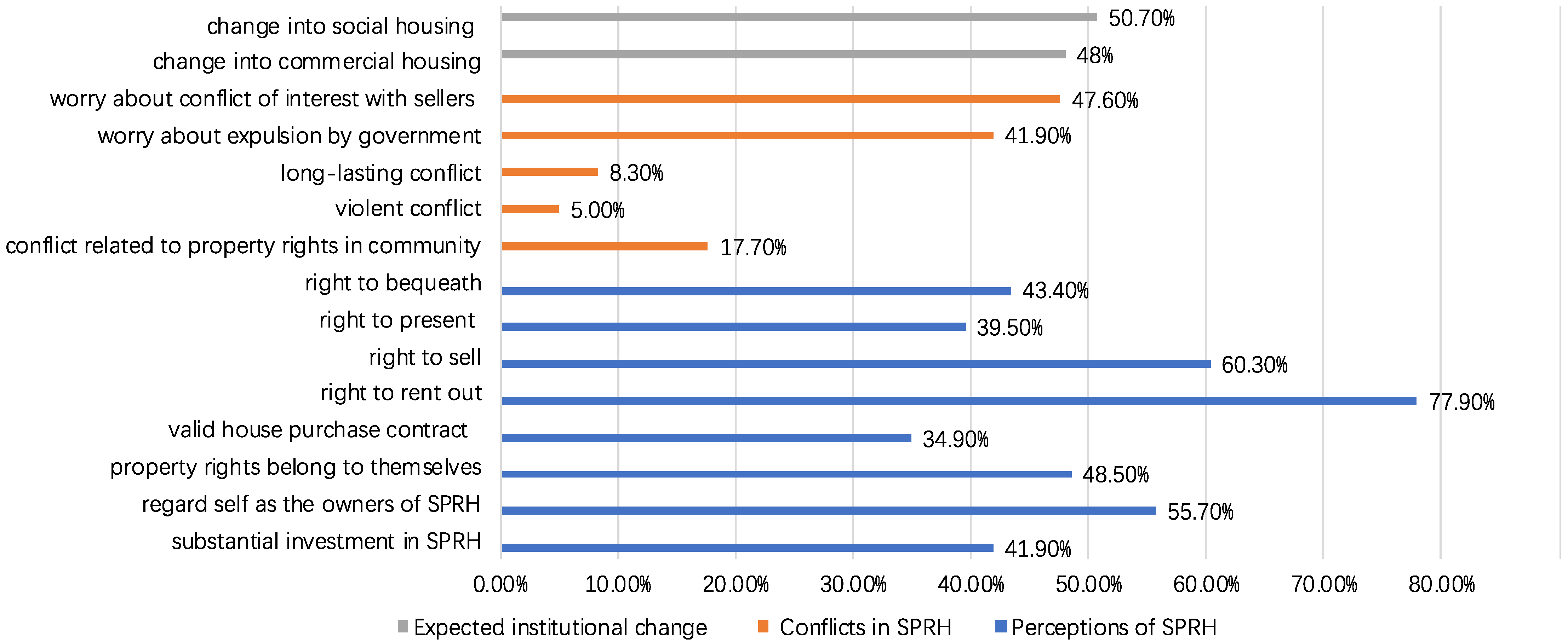

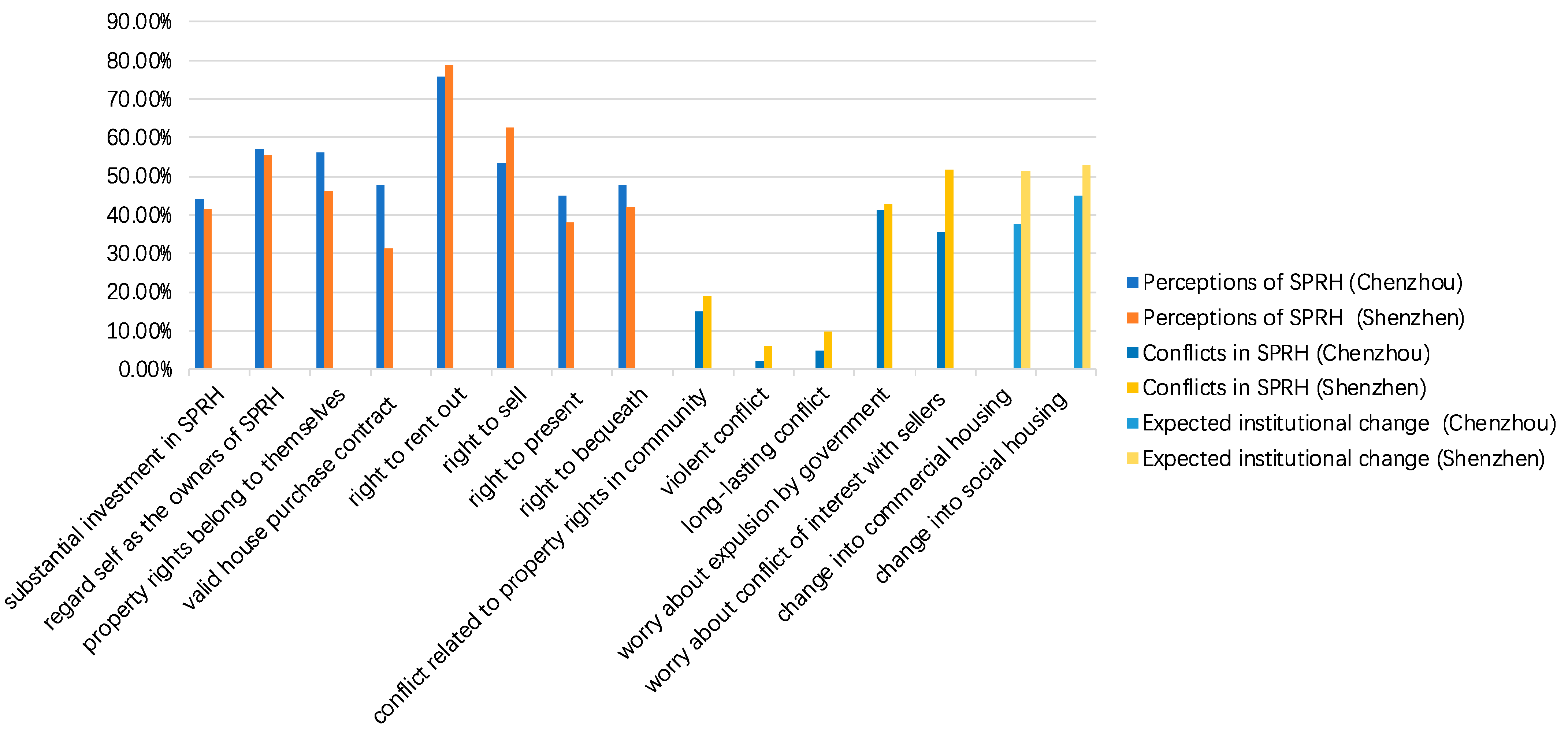

4.1. The Credibility of SPRH and the Substitutability of Institutional Functions

4.2. The Impacts of Substitutability and Other Factors

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Scale Value | Statement |

|---|---|

| 1 | Two indicators are equally important |

| 3 | One indicator is slightly more important than the other |

| 5 | One indicator is moderately more important than the other |

| 7 | One factor is intensively more important than the other |

| 9 | One factor is definitely more important than the other |

| 2, 4, 6, 8 | Median of judgement |

| Reciprocal | aij = 1/aji |

References

- Chen, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, Q. Rule by law, law-based governance, and housing prices: The case of China. Land 2021, 10, 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, C.; Choi, M.J. The causal structure of land finance, commercial housing, and social housing in China. Int. J. Urban Sci. 2019, 23, 286–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Ho, P. Formalizing informal homes, a bad idea: The credibility thesis applied to China’s “extra-legal” housing. Land Use Policy 2018, 79, 891–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Cai, Z.; Qian, Y.; Chen, F. Identifying urban poverty using high-resolution satellite imagery and machine learning approaches: Implications for housing inequality. Land 2021, 10, 648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, D.; Yau, Y.; Hou, H.; Liu, Y. Factors influencing the project duration of urban village redevelopment in contemporary China. Land 2021, 10, 707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Li, L. Efficiency evaluation of industrial waste gas control in China: A study based on data envelopment analysis (DEA) model. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 179, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Yang, W.; Wang, J.; Zheng, X. Analysis of the Effectiveness of Air Pollution Control Policies based on Historical Evaluation and Deep Learning Forecast: A Case Study of Chengdu-Chongqing Region in China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, P. An endogenous theory of property rights: Opening the black box of institutions. J. Peasant Stud. 2016, 43, 1121–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ho, P. In defense of endogenous, spontaneously ordered development: The institutional structure of China’s rural urban property rights. J. Peasant Stud. 2013, 40, 1087–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayek, F.A. Law, Legislation and Liberty; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- North, D. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Libecap, G.D. Contracting for Property Rights; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Understanding Institutional Diversity; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Coccia, M. An introduction to the theories of institutional change. J. Econ. Libr. 2018, 5, 337–344. [Google Scholar]

- Alston, L.; North, D.; Thráinn, E. Empirical Studies in Institutional Change (Political Economy of Institutions and Decisions); Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Greif, A.; Laitin, D.A. Theory of endogenous institutional change. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 2004, 98, 633–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, P. Institutional function versus form: The evolutionary credibility of land, housing, and natural resources. Land Use Policy 2018, 75, 642–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dixon, A.D. Function before form: Macro-institutional comparison and the geography of finance. J. Econ. Geogr. 2012, 12, 579–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.J. Institutional Change and Economic Development; United Nations University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Aron, J. Growth and institutions: A review of the evidence. World Bank Res. Obs. 2000, 15, 99–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Parsons, T. The Social System; Routledge: London, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A.D. The Concept of Social Change: A Critique of the Functionalist Theory of Social Change; Routledge: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Coser, L.A. The Functions of Social Conflict; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Dahrendorf, R. Classes and Class Conflict in Industrial Society; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H. Institutional credibility and informal institutions: The case of extra-legal land development in China. Cities 2020, 97, 102519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Ho, P. A model for inclusive, pro-poor urbanization? The credibility of informal, affordable “single-family” homes in China. Cities 2020, 97, 102465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. The credibility of slums: Informal housing and urban governance in India. Land Use Policy 2018, 79, 876–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, P. Unmaking China’s Development: Function and Credibility of Institutions; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tsao, H. The political economy of “minor property right” houses in rural China: An analysis of the property rights model. Chin. Political Sci. Rev. 2012, 53, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Y.; Huang, Z. The path of transforming small property right house into social housing. Mod. Econ. Res. 2011, 2, 29–33. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, Y.; Zheng, X.; Choy, L.H.; Wang, J. Property rights and housing prices: An empirical study of small property rights housing in Shenzhen, China. Land Use Policy 2017, 68, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Wang, D.; Webster, C.; Chau, K.W. Property rights with price tags? Pricing uncertainties in the production, transaction, and consumption of China’s small property right housing. Land Use Policy 2019, 81, 424–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.Z.; Cai, J.M. Institutional arrangement for rural land and collective actions from the farmers. J. Financ. Econ. 2009, 35, 85–93. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, F. Housing of limited property rights: A paradox inside and outside Chinese cities. Hous. Stud. 2009, 24, 825–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, S. Small property, big market: A focal point explanation. Am. J. Comp. Law 2015, 63, 197–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Z.S.; Xu, B.H.; Zhao, H.P. Big social concerns reflected from SPR housing in China. Rural Econ. 2009, 2, 12–15. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Q. China’s rural reform: State and institution changes in power relations—A review of the history of economic system changes. China Soc. Sci. Q. 1994, 8, 61–84. [Google Scholar]

- National Bureau of Statistics. Statistics of National Economic and Social Development. Available online: https://data.stats.gov.cn (accessed on 25 December 2020).

- Sun, X.; Zhou, F. Land finance and the tax-sharing system: An empirical explanation. Soc. Sci. China 2013, 4, 40–59. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, C.C. The elite, the natives and the outsiders: Migration and labor market segmentation in urban China. Ann. Am. Geogr. 2002, 92, 103–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solinger, D.J. Contesting Citizenship in Urban China: Peasant Migrants, the State, and the Logic of the Market; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Yi, D.; Zheng, S. Small property rights housing in major Chinese cities: Its role and the uniqueness of dwellers. Habitat Int. 2018, 77, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; De Meulder, B.; Cai, X.; Hu, H.; Lai, Y. Linking social housing provision for rural migrants with the redevelopment of “villages in the city”: A case study of Beijing. Cities 2014, 40, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.Y.; Yang, J.F.; Liu, W.W.; Wang, H. Institutional credibility measurement based on structure of transaction costs: A case study of Ongniud Banner in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region. Ecol. Econ. 2019, 159, 212–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenzhou Statistical Year Book 2020. Available online: http://tjj.czs.gov.cn/sjfb/50204/index.htm (accessed on 25 January 2021).

- Shenzhen Statistical Year Book 2020. Available online: http://tjj.sz.gov.cn/zwgk/zfxxgkml/tjsj/tjnj/content/post_8386382.html (accessed on 20 January 2021).

- Implementation Plan of Shenzhen Housing Development in 2020. Available online: http://zjj.sz.gov.cn/attachment/0/686/686843/7839321.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2021).

- Publicity of the Application Objects List for the Allocation of Public Housing in Chenzhou. Available online: http://app.anrenzf.gov.cn/html/zwgk/52579/52580/52592/52597/index.htm (accessed on 20 January 2021).

| Category | Variable(s) | Measurement(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | Credibility of SPRH or OSP | (1) Score from buyer’s perception of the SPRH institution (2) Score from buyer’s perception of conflict (3) Score from buyer’s perception of changing SPRH |

| Independent variables | CH | (1) Price-to-income ratio of commercial housing surrounding SPRH or the housing-price-to-income ratio (HPIR) (2) Price ratio between a small property rights house and a commercial house or the SPRH-price-to-commercial-housing-price ratio (SCR) |

| SH | Availability of social housing (ASH): 1 = very difficult, 2 = difficult, 3 = neither easy nor difficult, 4 = easy, 5 = very easy | |

| Control variables | Geographical location | Distance to the CBD (measured in km) |

| Third-party security agency | 0 = no, 1 = yes | |

| Income of buyer | Annual income of the buyer in the SPRH community | |

| Education level of buyer | 1 = junior middle school degree, 2 = high school degree, 3 = technical school degree, 4 = college or university degree, 5 = master’s degree and above | |

| Age of buyer | 1 = 18–30, 2 = 31–40, 3 = 41–50, 4 = 51–60, 5 = above 60 | |

| Gender of buyer | 0 = male, 1 = female |

| Variable | Total | Chenzhou | Shenzhen | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 458 | 23.60% | 76.40% | |

| Age | 18–30 | 30.10% | 24.10% | 32.00% |

| 31–40 | 41.10% | 24.30% | 43.10% | |

| 41–50 | 21.80% | 25.00% | 20.90% | |

| 51–60 | 5.70% | 12.00% | 3.70% | |

| >60 | 1.30% | 4.60% | 0.30% | |

| Gender | Male | 48.20% | 44.40% | 49.40% |

| Female | 51.80% | 55.60% | 50.60% | |

| Education level | Junior middle school | 3.50% | 13.90% | 0.30% |

| High school | 5.90% | 20.40% | 1.40% | |

| Technical school | 19.20% | 45.30% | 11.20% | |

| College/university | 62.00% | 17.60% | 75.70% | |

| Master’s or above | 9.40% | 2.80% | 11.40% | |

| Annual income | Min. | CNY 11,000 | CNY 11,000 | CNY 14,500 |

| Max. | CNY 2,000,000 | CNY 210,000 | CNY 2,000,000 | |

| Mean | CNY 214,233.38 | CNY 46,466.7 | CNY 266,001.4 |

| Variable | Overall | Chenzhou | Shenzhen | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perception of SPRH | Min. | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Max. | 8.00 | 8.00 | 8.00 | |

| Mean | 4.02 | 4.25 | 3.96 | |

| Perception of conflicts | Min. | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Max. | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 | |

| Mean | 1.21 | 0.99 | 1.35 | |

| Institutional change | Min. | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Max. | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | |

| Mean | 0.99 | 0.82 | 1.04 | |

| Overall supportive perception (OSP) | Min. | −2.00 | −2.00 | −2.00 |

| Max. | 3.20 | 3.20 | 3.20 | |

| Mean | 0.93 | 1.14 | 0.83 | |

| HPIR | Min. | 2.75 | 2.75 | 3.60 |

| Max. | 300.00 | 266.67 | 300.00 | |

| Mean | 29.85 | 44.52 | 25.27 | |

| SCR | Min. | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.09 |

| Max. | 1.33 | 0.87 | 1.33 | |

| Mean | 0.31 | 0.25 | 0.33 | |

| ASH | Min. | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Max. | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 | |

| Mean | 3.22 | 2.56 | 3.43 |

| HPIR | SCR | ASH | Age | Gender | Income | Education Level | Third-Party Agency | Geographical Location | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPIR | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| SCR | −0.106 * | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| ASH | 0.055 | 0.16 ** | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Age | −0.090 | −0.067 | −0.273 ** | 1 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Gender | −0.073 | 0.153 ** | 0.104 * | −0.046 | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| Income | −0.306 ** | 0.011 | 0.138 ** | −0.131 ** | −0.072 | 1 | - | - | - |

| Education level | 0.036 | 0.182 ** | 0.246 ** | −0.327 ** | 0.049 | 0.310 ** | 1 | - | - |

| Third-party agency | 0.008 | 0.07 | 0.225 ** | −0.201 ** | 0.07 | 0.187 ** | 0.219 ** | 1 | - |

| Geographical location | −0.199 ** | −0.174 ** | −0.251 ** | 0.109 * | −0.076 | −0.215 ** | −0.370 ** | −0.128 ** | 1 |

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | t | Coefficient | t | Coefficient | t | |

| HPIR | −0.039 | −2.599 ** | −0.048 | −3.249 ** | −0.045 | −3.083 ** |

| SCR | - | - | −1.422 | −4.661 *** | −1.184 | −3.881 *** |

| ASH | −0.082 | −2.107 ** | - | - | - | - |

| Education level | - | - | - | - | −0.183 | −3.242 ** |

| Third-party agency | - | - | - | - | −0.219 | −2.237 * |

| R2 | 0.025 | 0.061 | 0.110 | |||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.021 | 0.057 | 0.092 | |||

| N | 458 | 458 | 458 | |||

| Variable | Model 4 | Model 5 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | t | Coefficient | t | |

| HPIR | −0.004 | −2.173 ** | −0.013 | −2.643 ** |

| SCR | −3.875 | −6.448 *** | −3.367 | −5.273 *** |

| ASH | −0.163 | −2.10 ** | - | - |

| Education level | - | - | −0.222 | −2.048 ** |

| Third-party agency | - | - | −0.547 | −2. 441 * |

| Geographical location | - | - | −0.004 | 1.269 ** |

| R2 | 0.416 | 0.448 | ||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.399 | 0.426 | ||

| N | 108 | 108 | ||

| Variable | Model 6 | Model 7 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | t | Coefficient | t | |

| HPIR | - | - | - | - |

| SCR | - | - | - | - |

| ASH | 0.249 | 2.516 * | 0.224 | 2.311 * |

| Annual income | - | - | 1.217 × 10−6 | 2.142 * |

| Third-party agency | - | - | 0.769 | 3.311 ** |

| R2 | 0.018 | 0.064 | ||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.015 | 0.055 | ||

| N | 350 | 350 | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, Z.; Yau, Y. The Small Property Rights Housing Institution in Mainland China: The Perspective of Substitutability of Institutional Functions. Land 2021, 10, 915. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10090915

Zhou Z, Yau Y. The Small Property Rights Housing Institution in Mainland China: The Perspective of Substitutability of Institutional Functions. Land. 2021; 10(9):915. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10090915

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Ziqi, and Yung Yau. 2021. "The Small Property Rights Housing Institution in Mainland China: The Perspective of Substitutability of Institutional Functions" Land 10, no. 9: 915. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10090915

APA StyleZhou, Z., & Yau, Y. (2021). The Small Property Rights Housing Institution in Mainland China: The Perspective of Substitutability of Institutional Functions. Land, 10(9), 915. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10090915