Abstract

In the rapid urbanization and land development process, the integration of urban and rural areas has accelerated. Alongside this trend, the sustainable operation of suburban villages in metropolitan areas face many difficulties and challenges, especially in terms of the efficient use of land and the coordination of stakeholders’ interests. However, there remains a lack of systematic case studies in the literature targeted toward suburban villages in metropolises. This study selects three typical suburban villages in the metropolis of Jiangning District, Nanjing (i.e., a metropolis in China) to narrow this research gap. We collected primary data based on field investigations, structural interviews, and professional documents. With three typical villages employed as comparative case studies, we developed a theoretical framework to systematically analyze the operation process and the challenges faced by suburban villages in the metropolis. The results revealed the different application scenarios of three stakeholder-led models, including the state-owned enterprise-led model, the grassroots government-led model, and the private capital-led model, in the sustainable operation of metropolis-based suburban villages. The findings shed new light on selecting an appropriate path to boost the sustainable endogenous development of rural areas. This study extends existing research on the sustainable operation of suburban villages in the metropolis, providing practical guidance on aligning stakeholder-led models to better integrate urban and rural areas.

1. Introduction

Since 2007, more than 50% of the world’s population has lived in cities. Given the global urbanization trend, this proportion is expected to rise to 60% by 2030 [1]. Accompanying this trend, as a large number of village residents move towards cities, there is a resulting outflow in the labor force. Meanwhile, the demand for services in villages decreases, local industries decline, and the spiraling rise of a village recession seems inevitable [2]. The widening gap between urban and rural development has become a huge challenge all over the world. Both developed and developing countries, such as the United States [3], Canada [4], Sweden [5], Japan [6], Vietnam [7], and China [8], have all experienced rural recessions. For instance, in China, natural villages refer to rural settlements formed spontaneously and naturally [9]. On this basis, there is an increasing need for rural revitalization [10]. The United Nations 2030 agenda for sustainable development further emphasizes the need to establish interdependent and interrelated urban-rural linkages in its sustainable development goals [11]. Since 2012, the Chinese government has also proposed a series of strategies for rural revitalization. Currently, the urbanization of China demonstrates a distinctive characteristic (i.e., integration of urban and rural development). Both villages and cities are cornerstones in the realization of rural revitalization. Against this background, suburban villages in the metropolis are especially crucial because they serve as bridges between cities and villages.

China has launched a large-scale rural construction project in the wave of urban-rural spatial transformation, and the living environment and infrastructure conditions have improved during this period [12]. A construction project typically experiences three significant stages: planning and design, construction, and operations. When the construction of a project is completed, the project moves into the operation stage. During the project operation stage, both economic and social benefits are expected to be gradually obtained during a relatively long period [13]. However, the implementation of construction projects relating to the living environment and infrastructure has reached a bottleneck. More specifically, several featured villages have stagnated after a short period of glory and have ultimately run into operational difficulties (e.g., lack of continuing financial support and internal impetus). Thus, it is crucial to adapt to the rural operation era and achieve long-term sustainable development. With increasing government investment in rural infrastructure, the gap between urban and rural areas has dramatically reduced. Against this background, the focus on suburban villages in the metropolis has gradually transformed from improving habitat environment to the sustainability of operation processes [14]. In addition to traditional government-led programs, considerable capital from the private sector has emerged in rural areas to explore new space for business growth. In the wave of rural construction, industries, such as the bed and breakfast (B&B) industry [15] and the characteristic tourism industry [16], have rapidly developed.

In recent years, there is growing research interest in rural revitalization across different stages of rural revitalization projects (i.e., planning and design, construction, and operation and maintenance). First, prior studies usually selected a specific type of rural village for in-depth case studies, such as “hollow village” [17] and “historical village” [18]. However, there remains a lack of systematic case studies targeted toward suburban villages. Second, Habiyaremye et al. summarized the governance mode of rural transformation, with increasing attention accorded to the diversified factors affecting rural development. However, most studies have primarily focused on analyzing the impact of a specific type of governance model on a single village from multiple dimensions, such as land use, spatial layout, economy, society, and culture [19,20]. Currently, there is a dearth of research targeted toward the differences in those governance models in promoting the sustainable development of villages. Third, existing research mainly focused on rural environmental design [21], characteristics of developmental elements [22], primary stakeholder behavior [23], rural governance mechanisms [24], government project investment [25], and land financial policy [26,27,28]. These studies concentrated on the rural building boom and analyzed its critical success factors, contributing to an in-depth understanding of rural development’s design and construction stage [12,29]. Nevertheless, there is a lack of research on the transformation of suburban villages in metropolises under the intervention of multiple stakeholders in the operation stage. Thus, it is challenging to provide proactive and practical assistance in suburban villages’ high-quality and sustainable development over a relatively long period of operation.

This study carries out a comparative case analysis on the rural governance model dominated by different central stakeholders in the operational stage of suburban villages. The applicability of different rural governance modes is discussed, guiding the selection of appropriate paths to cope with the ongoing recession and developmental bottleneck faced by suburban villages. In summary, this study is guided by the following two research questions (RQ):

- RQ1: What are the challenges faced by suburban villages in the metropolis during the operational stage?

- RQ2: What is the scope of applying different governance models for the suburban villages in the metropolis?

This study selected three suburban villages in the metropolis of Jiangning District, Nanjing City, which incorporates three typical stakeholder-led models: the state-owned enterprise-led model, the grassroots government-led model, and the private capital-led model to address these two research questions. After that, this study carried out an in-depth comparative analysis of the challenges faced by suburban villages. Finally, by comparing and analyzing the application scenarios of the three typical governance paths, this study sought to guide villages entering the stage of high-quality operation and development.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Rural Operation and Rural Governance

According to UN-Habitat [21], the world is divided into thriving urban areas, semi-thriving peri-urban areas, and declining rural areas. Urban (including peri-urban) and rural areas need to leverage each other’s strengths for better development. Potential stakeholders, including local and superior governments, business enterprises, and social organizations, have attracted extensive attention during the development process. In particular, governance is emphasized as a critical aspect engendering interactions, partnerships, and interdependences in rural areas.

The rural decline is a common challenge around the world. In this context, different from urban development strategies [22], the United States, South Korea [23], Japan [24], Germany [25], Saudi Arabia [26], and other countries have explored targeted strategies for developing high-quality rural areas with the intent of addressing the polarization of urban and rural areas. Under the background of implementing the rural revitalization strategy and urbanization, emerging economies (e.g., China) have made significant attempts at urban-rural transformation. With the village environment and supporting facilities improving, many villages have experienced developmental pains and dilemmas [27]. For instance, rural construction projects primarily rely on government financial investment. The homogenization of the rural landscape and the lack of internal impetus and professional operations constrain rural areas’ sustainable operation [28] and can even become an obstacle in reaching endogenous development. Endogenous development focuses on collaborating with local communities to utilize people’s resources, strategies, and initiatives as the basis for their development [29].

Under the background of China’s comprehensive rural revitalization strategy, suburban villages in the metropolis, as relatively leading villages in development, are facing transformation from the current 1.0 version, with its emphasis on improving the habitat and environment, to era 2.0, which emphasizes operation and maintenance [30]. In the context of rapid urban-rural transformation, people’s activities of “consuming” the villages and looking for “nostalgia” are proliferating. The demand for collective ecological and leisure consumption in high-density urban areas can only be satisfied by rural areas. Due to the advantages of convenient transportation and proximity to the metropolis and surrounding areas, the functions of the urban-rural junction are closely combined under the reorganization of metropolitan areas [31].

The governance of villages is mainly realized by superior government, township government, local subdistrict, village committee, private capital, and social organizations. In general, the different levels of government perform two essential functions in rural governance [32]. The first function is to provide public goods for the community residents, such as public security, rural education, small-scale water conservancy facilities, rural road construction, social relief, flood control and disaster relief, community environment, health and epidemic prevention. The second function is to carry out tasks assigned by different administrative levels, involving the central government, provinces, prefectures, and counties. With the promotion of urban-rural integration, there have appeared several transformations in the governance process: from the omnipotent and multi-functional government to limited-function government; from top-down, administrative directive, campaign, working and governance models to mass participation, top-down and bottom-up combined work modes; from top-down, administrative-dominant government to autonomy government; and from the instruction-guided government to service-oriented government [17]. The sustainable development of rural areas relies on grassroots government and, more importantly, stakeholders participating in rural development. The option of governance models is mainly dependent on the village’s situation and development opportunities [33].

2.2. Different Stakeholders-Led Models

Given the increasing prosperity of stakeholders, the governance theory is broadly discussed. In this context, the relationship between multiple stakeholders in rural governance is increasingly highlighted. Woods proposed the concept of “relational rural”, which illustrates that globalization and urbanization have closely linked rural development with cities, rendering the flow of elements between villages and the world and between villages and towns more convenient [34]. Woods [35] also proposed the concept of “global villages” to describe how villages are embedded in a global network of capital, labor, and commodity. “Capital re-entry rural areas” have become an attractive research topic in recent years. Wu et al. hold certain reservations about industrial and commercial capital entering rural areas [36]. In villages, there are different types of stakeholders-led models, such as government-led, industrial and commercial enterprise investment, rural endogenous force promotion (e.g., villagers and rural enthusiasts), and social organizations involvement (e.g., non-profit organizations). Different stakeholders carry out various activities and practices in the villages, with different demands, but all imply the pursuit of sustainable rural rejuvenation in China [37].

First, under the support of multiple preferential agricultural policies, rural areas have increasingly become the key areas of public financial investment. Governments at all levels invest in a variety of rural planning and construction projects in rural areas. The government is the initiator of rural revitalization and a crucial stakeholder in practice [38]. Government-led village projects make gradual attempts to use the power of multiple stakeholders to participate in various stages of construction and maintenance [36]. Second, under the background of rapid urbanization, industrial and commercial enterprises [38] saw the massive value of rural land resource assets leading the flow of elements (including labor force, capital, and technology) from cities to rural areas. Currently, there are a series of challenges for private enterprises to participate in rural construction and operation, such as the distortion of government goals and the erosion of farmers’ interests [25,39]. Third, the rural endogenous force contributes to the development of rural projects. In villages, the original villagers tend to be more concerned about the benefits obtained in the short term. Many original villagers have a positive attitude toward demolition because they can obtain considerable compensation [40]. With the implementation of a rural revitalization strategy, a growing number of villagers return to their hometowns to start their businesses. Rural enthusiasts create their own space in a village because of personal emotional ties to the village and professional interests [41]. Fourth, non-profit organizations (NGOs) and charitable organizations primarily promote the spontaneous regeneration of villages through volunteer teams (involving professionals in culture, architecture, planning, and marketing) and form innovative public welfare attempts [42,43].

2.3. Framework for Understanding the Rural Governance Structure of Suburban Villages in the Metropolis

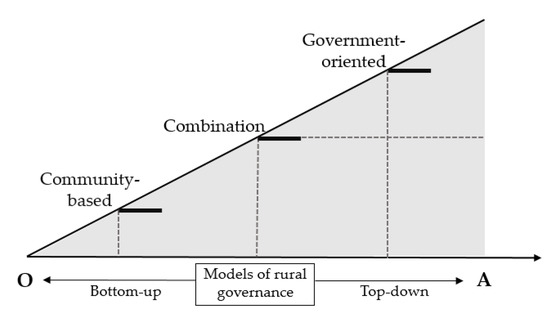

Multilevel governance is increasingly embraced as an analytical framework for complex problems [44]. Multilevel governance sits in contrast to a decentralized and bottom-up approach that hinges on local communities [44] or a top-down and hierarchical approach that emphasizes government control [45]. This perspective distinguishes the role of the community-based and government-oriented approaches in the governance process.

Figure 1 shows the rural governance spectrum of suburban villages in the metropolis [17]. The capital letter O represents the original point that refers to a totally community-based approach; the capital letter A is an endpoint representing a completely government-oriented approach. Thus, the left side shows the governance structures entirely dominated by the market, whereas the government fully leads the right. When approaching point O, the governance model is based on a bottom-up style. The villagers and civic society, such as the village council at the core of the governance structure, would independently manage the rural operation, including decision-making on projects, positioning the resettlement pattern with its planning, design, implementation, investment, and financing. In such a model, the government is not directly involved in a specific practice process. On the contrary, when getting closer to point A, the governance model is led by the government in a top-down style with a relatively low level of public participation, in which the public is more passively informed rather than actively involved. When there is more governmental administrative control, villagers will be more passive and less involved in the rural operation of suburban villages in the metropolis.

Figure 1.

The theoretical framework of rural governance structure.

As shown in Figure 1, the combination refers to an intermediate state between the bottom-up and top-down models in rural governance. This governance structure is neither wholly dominated by the villagers nor entirely dominated by the village committee or the government. It is a multi-center governance structure composed of the villagers, the village committee, NGOs, private enterprises, and the government. In the process of rural development from the traditional focus on the habitat and environment improvements to a focus on sustainable rural operations, the village committee and NGOs, as the core of the governance structure, are increasingly responsible for the overall planning, resettlement of migrants, and supervision of the implementation of the development trend. The government acts as the coordinator and the provider of public services, and the villagers who participate simultaneously have rich resources, adaptive capacity, and active participation. In this governance structure, decisions are not limited to a single actor, but are determined by the roles and responsibilities of the major players. Moreover, there are a diverse set of participants in different villages, which is caused by their differences, and participation also has its own characteristics. This situation is an organic combination of top-down and bottom-up approaches, where key participants flexibly perform their responsibilities, maximizing the project’s benefits based on joint consultation and shared governance.

3. Research Methods

3.1. Analytical Framework

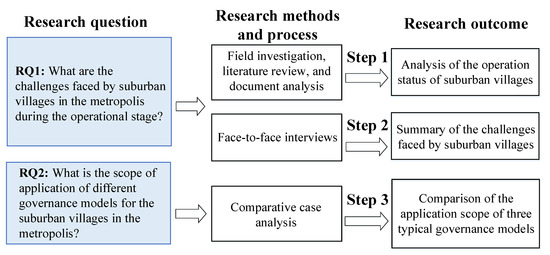

The analytical framework of this study is shown in Figure 2. First, based on a field investigation, literature review, and document analysis, the operation status of suburban villages in the metropolis was analyzed. Second, according to face-to-face interviews, the challenges faced by suburban villages were summarized. Third, through comparative case analysis, this study sought to demonstrate three different paths of suburban villages’ operation and the application scope of their governance models.

Figure 2.

Analytical framework.

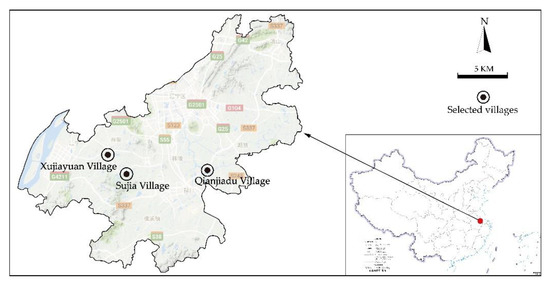

A case study is appropriate for discussing and building theories where a holistic, in-depth investigation is needed [46,47]. By examining a small number of intensively investigated cases, in-depth insights can be formed [48]. Given this, comparative case studies were conducted for empirical analysis to illustrate and interpret the multiple parties involved in suburban villages in the metropolis to examine our proposed theoretical framework. On-site interviews were conducted to obtain comprehensive information on multi-participatory practice in the metropolis-based suburban villages. This study selected three villages in Jiangning District, Nanjing, Jiangsu Province as the research subjects. Jiangning District is typical of China’s eastern coastal areas entering the 2.0 rural revitalization period, with its emphasis on operation and maintenance. We focused on three representative villages that could effectively reflect the typical types and actual situations of multi-stakeholder participatory practice in suburban villages in the metropolis of Jiangning: (1) Xujiayuan village (XJY) in the Guli Subdistrict, (2) Qianjidu village (QJD) in the Hushu Subdistrict, and (3) Sujia village (SJ) in the Moling Subdistrict.

3.2. Study Area

Jiangning District, Nanjing City, was one of the first areas in China to enter post-industrialization and post-urbanization. Relying on its locational advantages and strong development foundation as a typical suburban area, Jiangning District has carried out a series of explorations on sustainable rural operation and has accumulated considerable long-term development and maintenance experience. After going through the pilot demonstration stage (2010), the demonstration area construction stage (2013), and the overall planning and construction stage (2017), villages in Jiangning entered the high-quality developmental stage after 2017. Specifically, Jiangning explored the differentiated development and maintenance aimed at the sustainable development of villages. In this stage, different forms of rural development models gradually appeared. Compared to the traditional government-led model, more stakeholders participate in these rural development models. This study selected three typical rural development and maintenance types in Jiangning District, Nanjing City: state-owned capital oriented (QJD), social-capital oriented (SJ), and grassroots-government oriented (XJY). The location and main characteristics of the three case study areas are shown in Figure 3 and Table 1, respectively.

Figure 3.

Location of the three case study areas.

Table 1.

Essential characteristics of the three case study areas.

3.3. Data Collection and Methods

The data and materials in this study were primarily collected through extensive field investigation and face-to-face interviews. We also obtained second-hand information from the Jiangsu Government Service Network and official village planning schemes.

We first conducted a wide-ranging investigation in Nanjing in October 2019. Through field research in QJD, SJ, XJY, and four other villages, we gained a preliminary understanding of the current development and maintenance situation of rural areas in the Jiangning District. From December 2019 to June 2020, we conducted in-depth field investigations in QJD, SJ, and XJY. We collected a series of data concerning the details of village planning (e.g., blueprint, land consolidation, and infrastructure layout) and the implementation process of village operation (e.g., the village development situation and the relationship among multiple involved entities). Meanwhile, face-to-face interviews were conducted in QJD, SJ, and XJY. Specifically, we interviewed the current director of each village, 12 proprietors from different industries, such as bed and breakfast and catering service professionals, and the designers of SJ and XJY. With this basis, we developed a comprehensive understanding of the construction and operation of the villages. The detailed data collection process is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Details of the data collection process.

4. Comparative Case Studies

4.1. (Xujiayuan Village) XJY—Grassroots Government-Oriented

4.1.1. Overview of Village Construction and Operation

Located in Zhangxi Community, Guli Subdistrict, Jiangning District, Xujiayuan is one of the first groups of characteristic rural villages in Jiangsu Province (Figure 4). XJY is 4 km from Guli New Town, and is close to the rural greenway, which provides XJY with convenient transportation and an excellent geographical location. The village has a rich courtyard atmosphere and profound cultural heritage, surrounded by mountains, forests, and polder fields. With abundant wetland resources and a favorable ecological environment, a unique spatial pattern of “four polders (low-lying paddy fields surrounded by dikes) with one fold” was formed (Figure 5), making XJY a traditional agricultural village located south of the Yangtze River. In the second half of 2017, the Jiangning District Government and Guli Subdistrict carried out the planning, construction project, and operation of XJY, forming a rural operation and management mechanism of “government dominating, market maintaining and villagers participating.” In this mechanism, the Guli Subdistrict, as a grassroots government, plays a leading role in the land circulation, industrial development, and investment operation of XJY. By signing an agreement, most of the residents moved to Guli New Town. Although there were initially 43 families, now only 10 of them remain. The collective now owns the houses, and the village style was improved through a unified architectural renovation and environmental improvement. The cultivated land is transferred by the agricultural land stock cooperatives established by the subdistrict, primarily used for large-scale operation and exhibition. The Urban Farm Project has transferred 64 mu (One mu approximately equals to 666.7 square meters.) of arable land to the enterprise with a transfer fee of 1400 CNY/(mu · year), among which the minimum transfer fee of CNY 700 is for the farmer. The cultivated land for the exhibition has no direct income and is mainly sponsored by the subdistrict.

Figure 4.

Current situation of Xujiayuan village construction: (a) Xujiayuan community service station; and (b) sketch map of land share operation pilot.

Figure 5.

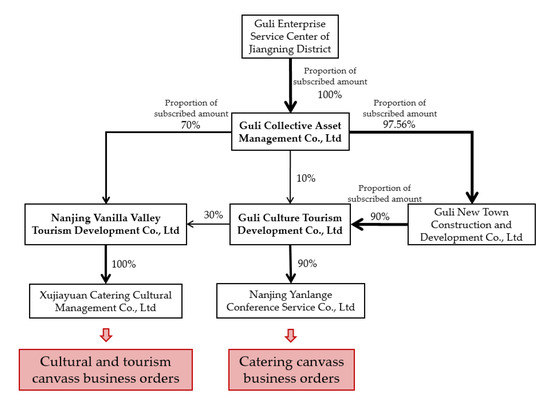

Collective asset management and construction platform for the Guli Subdistrict.

XJY adopted the industrial development path of “three parks co-construction and three industries linkage”. The subdistrict invested in ornamental flower planting and established a vegetable sales platform to promote the linkage of three industries online and offline, intending to integrate the local “Shuibaxian” and other agricultural products into the subdistrict’s “Chunniushou” brand. In the revitalization of the existing collective assets, the subdistrict implemented housing transformation and investment management. The organizational structure and controlling relationships between companies are shown in Figure 5. Guli Cultural Tourism Company is the subordinate company of Guli Collective Asset Management Co., Ltd. (10% shares) and Guli New Town Construction (90% shares). Guli Cultural Tourism Company carries out the investment promotion of the cultural tourism projects.

Meanwhile, Nanjing Xujiayuan Catering Cultural Management Company, the sole subsidiary of the Nanjing Vanilla Valley Tourism Development Co., Ltd., attracts public investment in promoting the catering industry. The projects are strictly screened before entering XJY. Projects with an investment of over CNY two million need to be discussed and implemented by the street party committee. The Xujiayuan café, noodle shop, farmhouse resort, B&B, handicraft workshop, and other shops were gradually opened, and the trial operation of the B&B had a high occupancy rate in 2019. Additionally, subdistrict tourism companies and provincial departments developed new medical and health functions and introduced third-party senior care institutions in XJY.

The health care industry is being further developed through joint operations to ensure the utilization and stable development of diversified resources in XJY. In terms of village governance, the home care service center and villager activity center were established to satisfy the needs of the public through subdistrict funding and social service purchase. Meanwhile, the subdistrict actively tried to inspire the power of local villagers. XJY has realized a certain degree of villager autonomy by revising the village rules and regulations and taking additional actions. XJY is gradually moving toward the benign interaction of agriculture, tourism, and the service processing industry.

4.1.2. Challenges in Village Construction and Operation: Participation Willingness of Multi-Stakeholders Remains to Be Inspired

Due to the limitations of the subdistrict management at the grassroots level, the villages dominated by the subdistrict face considerable disadvantages in terms of professional business operation. Most lack relevant experience and are faced with the reality of insufficient counterpart talents (Figure 6). Meanwhile, with the characteristics of strong social relations, the subdistrict is facing the challenge of openness and transparency in all aspects of investment promotion and operation. Therefore, mobilizing the active participation of villagers and various social organizations, and stimulating the endogenous power of village development are particularly critical.

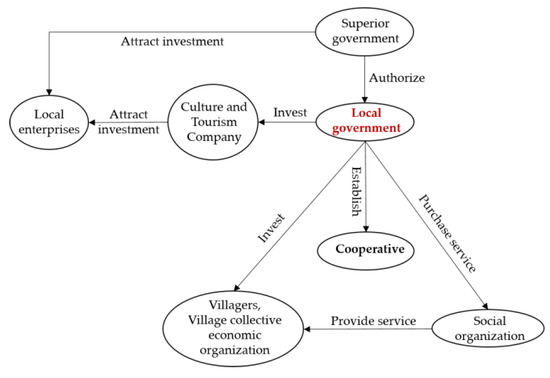

Figure 6.

Construction and operation relationship of multiple entities of Xujiayuan.

The model of XJY was promoted mainly by the subdistrict government (i.e., local government). The superior government authorized the local government to take charge of the whole construction and operation process. In addition, the superior government provides support to the local government to attract investment from private capital. On this basis, local government-sponsored local cooperatives, cultural and tourism companies, and village collective economic organizations are used to promote the projects and attract investments from private capital. Meanwhile, the local government also purchased comprehensive service from social organizations for the villagers and tourists (Figure 6).

In the development of XJY, the government devoted significant efforts and played a leading role. The propaganda of “think Guli, original dream” demonstrates the government’s enthusiasm for building XJY. However, rural revitalization is a complex and systematic project that the government cannot accomplish alone. Under the government’s proposal, most villagers moved to Guli New Town, with less than 20 households remaining in XJY. According to the results of the investigation, most of the people left behind are the aged. The healthy development of rural revitalization requires a group of professional talents to manage and understand the operation. The original villagers who were not relocated lack the corresponding professional capabilities and are difficult to integrate into the construction and operation of new villages, which results in low participation of the masses in the village construction projects. It can be seen that the subdistrict leader of XJY needs to further realize educational empowerment for the original villagers through professional training. Not only would this help them adapt to meet the talent requirements of this new stage and complete the transformation of the villagers’ identity, but it would also ensure the rights and interests in the local employment of villagers to the greatest extent possible.

4.2. (Qianjiadu Village) QJD—State-Owned Capital-Oriented Enterprise

4.2.1. Overview of Village Construction and Operation

QJD village is located in the Heping Community, Hushu Subdistrict, Jiangning District, Nanjing City. As one of the first groups of provincial pilot villages in Jiangsu Province, QJD is composed of two natural villages: Qianjiadu and Sunjiaqiao. As a typical suburban village in the metropolis, QJD is only 39 km from the main urban area and is close to the provincial road. This village is a typical canal town of south China (Figure 7). QJD was built and is operated by Nanjing Jiangning Tourism Industry Group Co., Ltd. (the tourism group), a state-owned company established by the Nanjing Jiangning District government. This tourism group invested about CNY 280 million in village construction and renovation, and adopted the strategy of relocation by agreement to resettle the original residents. After the villagers sign the relocation agreement, the subsequent relocation fee to compensate the villagers for the land transfer fee is 700 CNY/(mu · year), and the tourism group bears the annual plant compensation of 300 CNY/mu. About 80 percent of the original villagers moved out of the village, and the original house property rights, land, and paddy field use rights of the relocated villagers were handed over to the tourism group. The tourism group dredged the original water system and regulated about 2300 mu of land and paddy fields. In order to preserve the original style of QJD, the tourism group did not demolish the houses left by the original villagers. Instead, it strengthened the foundations and walls of the old houses on their original sites. Some houses were selected for further modification, with the roof of the wooden and glass structure raised to increase the houses’ transparency, beauty, and ornamental charm, forming several unique buildings in QJD.

Figure 7.

Current situation of Qianjiadu village construction: (a) renovated and constructed residential quarters; and (b) beautiful scenery in Qianjiadu village.

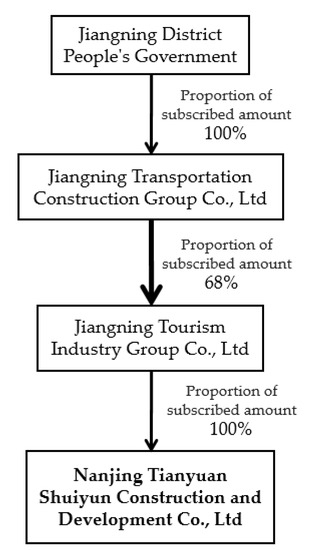

Industrial prosperity is the promise and foundation of rural revitalization. Under the guarantee of capital and the system, QJD formed a government-oriented rural operation and management mechanism, with state-owned enterprises as the main body, and has attracted the active participation of villagers (Figure 8). Since agriculture is the foundation of the rural areas and the foundation for developing other industries, the local community took the lead in establishing the Nanjing Runhe Agricultural Farmland Professional Cooperative, which the tourism group operates. The cooperative hired the original villagers to form a management team, namely a “farming group”, to cultivate the land and paddy fields, which were transferred from the villagers, to grow rice, shuibaxian (eight kinds of aquatic plants abound in Nanjing), and other crops. The production materials, such as rice seedlings, fertilizer, shovels, and labor remuneration, are all borne by the tourism group. The tourism group also established a “pro agriculture” brand to promote local agricultural products and sell these products to tourists (Figure 9). During the holidays, many urban tourists come to QJD, with most of the tourists being families who take their children to the village for an outing.

Figure 8.

Collective asset management and construction platform at Hushu Subdistrict.

Figure 9.

Construction and operation relationship of multiple entities of Qianjiadu.

QJD natural village is more inclined toward B&Bs in the tertiary industry, alongside two catering businesses. As a supplement, Sunjiaqiao natural village is dominated by the catering industry. In terms of village management, the tourism group is responsible for maintaining facilities, public services, public safety, and other affairs in the scenic village area. In contrast, the Heping community handles agriculture-related affairs and plays the middleman between the tourism group and villagers.

4.2.2. Challenges in Village Construction and Operation: The Management System Lacks Flexibility

Nanjing Jiangning Tourism Industry Group Co., Ltd., as a state-owned enterprise, has obvious defects in that it has poor operating flexibility. As an essential basis for maintaining social stability and national economic development, state-owned enterprises are relatively minor in profit-making compared with private capital, which makes them more orderly in terms of operation. On the other hand, theses state-owned enterprises lack the urgent need to promote the development of villages.

It is widely known that the agricultural industry is time-sensitive and relies primarily on nature. However, there are now many restrictions on the agricultural production mode and procedures during the collaboration with the professional agricultural land cooperatives, which has affected the efficiency of agricultural production. For example, farmers must report the production materials (such as seedlings, fertilizer, shovels, and gloves) needed to the cooperatives before transplanting seedlings. After the total demand of the cooperatives is reported to the person in charge of relevant affairs in the tourism group, the company will uniformly make purchases for the cooperatives and then distribute the materials to the farmers. Farmers use the materials uniformly, which results in missing optimal tillage time and often leads to a relatively low level of efficiency in agricultural production. In essence, there is a contradiction between the current emphasis on demonstration agriculture and the traditional planting habits of small-scale areas. In addition, state-owned enterprises, backed by government funds, generally pursue operational stability rather than revenue. In the early stage, the tourism group invested CNY 280 million in relocating the villagers of QJD. Several hundred million CNY is expected to be invested in improving the environment by dredging the water system in the polder field on the plain of the village. In addition, more than 100 employees are working in the village, and there are still wage expenses for the workers. However, to date, the current income is not sufficient to cover expenses. The state-owned enterprise platform is involved in village catering, homestay, and other endeavors, which are significantly less dynamic than private stores. As the income of state-owned enterprise platforms is not related to its employees’ wages, and there are many restrictions on employee work rules, enthusiasm for work is not strong. In addition, the operation philosophy of state-owned enterprises is relatively conservative, inflexible, and fails to keep pace with trends, thus prompting many customers to choose private stores that can provide customized services.

4.3. (Sujia Village) SJ—Private Capital Oriented

4.3.1. Overview of Village Construction and Operation

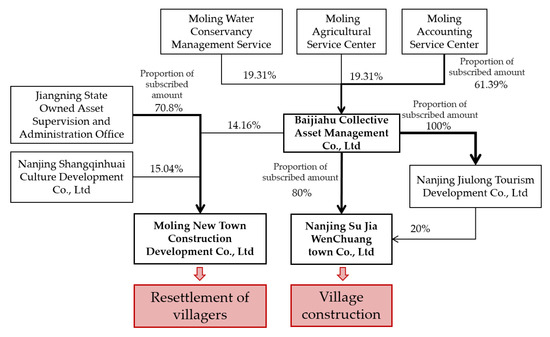

SJ village is located on Xipisu Road, Moling Street, Jiangning District, Nanjing City. It was built after the overall relocation of residents in the original natural village, Xipisu village. It is located at the west entrance of the beautiful village area in Jiangning District, with Bailu Lake to the east, Ginkgo Lake paradise to the west, Longshan reservoir to the south, Guli Subdistrict to the north, and Jiangsu Software Park behind it. It is one of the rare suburban villages with scenic spots in Nanjing (Figure 10). SJ ideal village is a project that was approved by the Xiangban Company (a private capital company) in 2015, under the name “Sujia cultural and creative town”, as the first cultural and creative town in the Yangtze River Delta. It is a unique attempt at a beautiful rural construction project in Jiangning District to enter the third stage of rural-led self-organizational development. Jiangning District, Nanjing City delegated part of the developmental rights to the subdistrict government. Specifically, the Jiangning District provides SJ with land resources, policy guidance, and financial support in establishing a government financing platform. The government financing platform company (i.e., Baijiahu Collective Asset Management Co., Ltd. in Shuanglong Road, Jiangning District, Nanjing City) is the subordinate company of the Moling Water Conservancy Management Service (19.31% shares), Moling Agricultural Service Center (19.31% shares), and Moling Accounting Service Center (61.39%). This platform company is responsible for the relocation and construction of villages (Figure 11). Before Xiangban Company entered the site, the Jiangning District Government invested CNY 200 million in demolition costs to move the original villagers of Xipisu village to Moling’s new town. In addition, the Jiangning District Government also undertook the construction of the entire village infrastructure, such as sewage treatment, drainage, water supply, and garbage treatment. It is said that “outside the small red line (i.e., boundary line of land), within the big red line (i.e., boundary lines of roads)” is the construction scope undertaken by the government.

Figure 10.

Current situation of Sujia village construction: (a) statue with village vision at the entrance of Sujia Village; and (b) communication with the village manager in Lvleyuan.

Figure 11.

Collective asset management and construction platform at the Moling Subdistrict.

SJ is a B&B cluster with the core goal of providing an excellent B&B experience. Excluding the micro B&Bs, there are eight B&B enterprises in SJ, with over 100 guest rooms and introductory prices of 800–1000 CNY/(room·night). Xiangban Company runs the whole park as a typical multi-cultural and entrepreneurial case. At present, Xiangban Company only owns a small number of industries in SJ, such as Yuanshe Pinghu, Pushe Qingshui, and some other self-operated high-end B&B brands. Xiangban Company rents out 20-year property rights for micro B&Bs with hosting services and distributes business invitations according to the area of the original house base. The total area is more than 20,000 units, with an overall rent of about 550,000 CNY/year, counting the total area of the original house base.

SJ includes many business operations, such as B&Bs, interactive manual workshops, and catering. Meanwhile, SJ can also provide hosting services to foreign residents. The main profits of rural partners in SJ come from the rent from housing investments and property trusteeship service fees. Other local profits primarily rely on the local team of SJ to achieve income through planning activities and other methods. After the investment promotion, the rural partners will assume the role of rural operation and integrate many types of businesses through the park, taking the rural image of SJ as the foundation. At present, the local SJ operations team has gradually realized localization. Among the more than 20 people on the team, over 70 percent of the team’s employees are from Jiangning. The other 30 percent are the managers and housekeepers of B&Bs. Xiangban Company has registered local companies in Nanjing. The team of SJ is expected to achieve actual localization within 10 years (Figure 11).

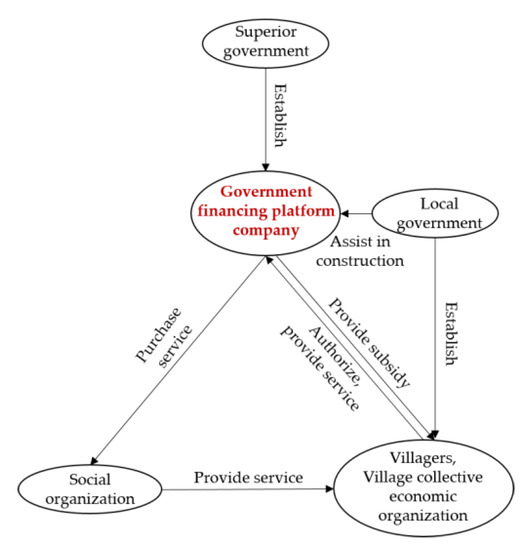

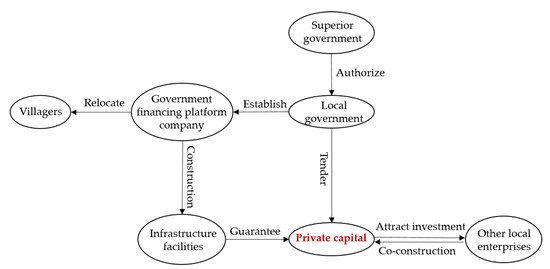

4.3.2. Challenges in Village Construction and Operation: Separation of Village Construction and Operation

There is a significant separation between village construction and rural operation in private capital oriented villages. The primary improvement of the human habitat and environment of the village is mainly led by governments, at all levels, and the government financing platform company. The superior government authorized the local government to form a government financing platform company. This platform company (i.e., Baijiahu Collective Assessment Management Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China) is responsible for infrastructure construction and the relocation of villagers, and guarantees operation conditions for private capital. The model of SJ was then promoted by the Xiangban Company (i.e., private capital attracted by the local government). The private capital was at the center of the whole operation process and attracted investment from other local enterprises and accomplished co-construction (Figure 12). Private capital primarily focuses on using various elements in the village to obtain flow and maximize benefits. The village has become a space carrier of urban, which is the core of almost every comprehensive urbanization under the rural shell.

Figure 12.

Construction and operation relationship of the multiple entities of Sujia.

Taking the SJ ideal village as an example, in leasing the villagers’ residential land by the township partner group, the local street government and the original villagers remain connected throughout the process. The township partner group does not have relations with the villagers, and the government acts as an intermediary in the communication between the villagers and the township partner group. Most of the original villagers have moved to Moling’s new town to earn a living and have no connection with SJ. There is only the Bailu Lake fish pond left, which has contracted with the subdistrict for a long period. Its consistent concept, which fits the SJ ideal village’s goal, meant it was able to stay after the entry of the Xiangban Company. The staff of SJ negotiated with the fish pond owner to unify the architectural style as much as possible. They have achieved a harmonious symbiosis and reached a relationship of mutual promotion between the fish pond, Bailu Lake, and other parts of the village.

Concerning the aspect of village governance, the highly autonomous model of SJ is similar to the park operations. However, various profit-making behaviors in its operation led to the gradual reduction of support from the local government. Additionally, SJ did not meet the expectations of the government after a five-year development period, and the government gradually adopted a cold attitude toward SJ. In this case, the most direct impact is that the government is no longer willing to undertake the maintenance and repair of the infrastructure in the village, and this part of the cost now falls to Xiangban Company. In order to balance the income and expenditures, the company may conduct additional activities to obtain benefits, which is even more contrary to the government’s will, deepening the contradiction between these two stakeholders and forming a vicious cycle. With the decrease in communication between the local government and the company, and the decrease in the exchange of resources, the information asymmetry will only become more serious. What is more, severe violations of laws and regulations may occur in the operation of villages without self-knowledge. If the government fails to detect and stop these violations, it may result in severe consequences.

One of the original intentions of the construction of SJ was to create a unique cultural tourist attraction to compel the surrounding middle class to consume and stay. Its format is based purely on service industries such as B&Bs and catering. The local permanent residents are only store operators. Taking the outbreak of COVID-19 in early 2020 as an example, the village itself existed in the form of an “isolated island” for nearly two months. Living, production, consumption, and other daily behaviors have not formed a positive interaction in this kind of park-style rural space. How to attract new villagers and address the relationship between new and original villages remains to be explored.

5. Discussion and Implications

In China, the models of rural governance are diversified due to the complexity of the development scenarios of villages. In light of China’s rural governance, prior studies summarized the development approaches into the top-down and bottom-up models [9,17,44]. With this basis, we further distinguished between stakeholders involved in suburban village operations and developed three stakeholder-led models (i.e., the state-owned enterprise-led model, the grassroots government-led model, and the private capital-led model), thereby shedding new light on the integration of urban and rural areas. Through the comparative analysis of the developmental characteristics of the three villages in Jiangning District, Nanjing City under the leadership of different stakeholders, this study showed the general predicament that the villages faced in the current high-quality operational stage (Table 3). This study demonstrated that making full use of the existing infrastructure conditions and mobilizing the village’s talent to achieve continuous operations are direct challenges faced by each village.

Table 3.

Comparison of stakeholder-led approaches of three metropolitan villages.

The analytical framework based on the analysis of the operational models from these three typical villages was applied to the comparative case study of the three villages of Xujiayuan, Qianjiadu, and Sujia. This allowed for the possibility of the village’s sustainable operation and management path in the high-quality developmental stage to be more fully explored.

- First, although the nature of the stakeholders in these three villages was different, in essence, there exists a separation between villager participation and the villages’ development. Under the relocation process, most of the villagers moved out of the villages [49]. Even in SJ, with all of the original villagers moving out, it has become a themed zone, with entertainment facilities and comprehensive services for tourists, instead of a residential area. Meanwhile, the land, houses, and other assets were gradually transformed into collective asset management and benefits. Neither the new villagers nor the original villagers were able to profit from the secondary development of such villages. The relatively effective participation of villagers in QJD was only facilitated to allow the villagers to benefit from labor through farming, which, to a certain extent, has deviated from the traditional understanding that villagers are the village owners [50];

- Second, different stakeholders have their relative advantages. In this study, the uniqueness of the villages focuses primarily on the natural endowment and traditional village context. How to effectively excavate these material elements and transform them into an impetus for village development is an urgent challenge for village operators [48]. Private capital is superior to the state-owned enterprise platform and the subdistrict because of its original nature of seeking profits. Regarding personnel quality and vision, the state-owned enterprise platform is more robust than the ordinary street. Taking the Xiangban Company as an example, this relatively innovative and professional private capital firm has developed many loyal customers in the early stages through festival activities, village brands, and Internet marketing.

- Third, under the background of the current rural revitalization, multiple stakeholders continue to participate in rural revitalization, attempting to strengthen the integration between urban and rural areas. It is crucial to understand how to more effectively handle the relationships between multiple stakeholders and promote the sustainable development of the village through practice. In the process of revitalizing the rural areas, different stakeholders hold expertise in different areas, such as the leading force of the government in the early stage, local construction projects on the village’s physical space, and the competition among various organizations, such as private enterprises, state-owned enterprises, and subdistricts, in the process of developing the characteristic villages [42]. Different leading stakeholders are selected for different villages according to their own characteristics, and other stakeholders are mobilized to cooperate together to boost the villages, inject new impetus, and identify a new direction.

Due to the limitations of the survey, this study only selects three typical villages in Jiangning District, Nanjing (i.e., a metropolis in China). The three cases adopted different governance models, led by various stakeholders, and have diversified application scenarios in terms of facilitating the sustainable operation of suburban villages. It extends the topic of the sustainable operation of suburban villages in the metropolis under the participation of multiple stakeholders through horizontal comparison and induction. As China is a vast country with diversified rural areas, the diversification of stakeholders involved in the high-quality developmental stage and the dilemma of village development are not entirely illustrated by three cases. In the future, more rural areas and operation types need to be added, especially cases with other types of central stakeholder participation in social bodies, to explore the sustainable revitalization of villages and the social effects of different central stakeholder involvement.

In addition, different models demonstrate various characteristics and thus these models are suitable for diversified contexts (Table 3). First, the subdistrict-oriented model is mainly suitable for regions with a developed internal governance structure and weak endowment. This model can make full use of limited resources and create conditions for rural revitalization. Second, the state-owned enterprise-oriented model applies to villages with a good industrial base. This model can stimulate the development of the village in a relatively short period. Third, the private capital-oriented model fits well for areas with flexible policies and adequate natural resources.

6. Conclusions

In the wave of rural revitalization, Jiangning District, Nanjing City has promoted rural construction projects in different stages. The key aims of these projects have turned from the initial aim of human habitat and environment construction to the current aim of high-quality characteristic development stage. At the same time, with the influx of multiple stakeholders into rural areas, there are a variety of operational attempts being made in the Jiangning District. This study examines three typical types: the grassroots-government-led operation of XJY, the state-owned enterprise-led operation of QJD, and the private capital-led operation of SJ. Through field investigation and data research, we determined that these three types have their own set of advantages and disadvantages. As the development of high-quality characteristics involves the long-term sustainable operation of the original short-term construction projects, the three central stakeholders are clearly making progress in their attempts.

Generally speaking, it is effective when the government improves the village habitat environment early. The early intervention of central stakeholders contributes to the alignment of the planning, design, and construction of suburban villages, thereby improving the profitability during the operation stage. Currently, the three types of governance are effectively combined with the characteristics of villages and have achieved the expected results. This study extended the rural governance spectrum to the suburban villages in the metropolis [51,52] and formed strategies for promoting urban-rural linkages from the perspective of different stakeholder-led models [21,22]. This study also provided specific benchmarks for suburban villages that enter the high-quality developmental stage.

However, in the three types of rural operation and governance paths, there are typical challenges pertaining to the lack of villager involvement. The three governance models mainly focus on the demands of business entities, whereas the original, relocated villagers only obtain the compensation of land transformation and some basic subsidies. Although the villagers’ engagement has increased significantly when compared to the earlier revitalization stages, the income of the original villagers has not yet significantly increased during this process. Whether it is grassroots government-oriented, state-owned enterprise-oriented, or private capital oriented, villages need to take advantage of the leading stakeholders’ resources, seizing opportunities in rural revitalization [53], assisting with government supervision, and contributing knowledge to the planning, design, construction, and operation of villages.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.L.; methodology, X.L. and G.W.; validation, X.L.; formal analysis, X.L. and C.Z.; data curation, X.L. and C.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, X.L.; writing—review and editing, X.L., G.W. and X.C.; supervision, G.W.; funding acquisition, G.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Project Number: 71901101), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, China (Program Number: 2021JC002), and the Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program for Undergraduates, Hubei Province, China (Program Number: S202010504257).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to Mingrui Shen, Nanjing University, for his comments and suggestions on this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- UN DESA Voice. Release of the World Urbanization Prospects: The 2018 Revision. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/undesavoice/more-from-undesa/2018/05/39869.html (accessed on 1 May 2021).

- Hara, T.; Ono, A. Marginal settlements and regional regeneration. Marg. Settl. Reg. Regen. 2009, 44, 69–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rechard, E.W. Survival of rural America: Small victories and bitter harvests. Choice Rev. Online 2009, 46, 4751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Markey, S.; Halseth, G.; Manson, D. Challenging the inevitability of rural decline: Advancing the policy of place in northern British Columbia. J. Rural Stud. 2008, 24, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedlund, M.; Lundholm, E. Restructuring of rural Sweden—Employment transition and out-migration of three cohorts born 1945–1980. J. Rural Stud. 2015, 42, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assmann, S. Sustainability in Contemporary Rural Japan: Challenges and Opportunities; Taylor and Francis Inc.: London, UK, 2018; ISBN 9781138476974. [Google Scholar]

- Thanh, L.H.; Nhat, L.T.; Dang, H.N.; Ho, T.M.H.; Lebailly, P. One village one product (OVOP)-A rural development strategy and the early adaption in Vietnam, the case of Quang Ninh Province. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Jia, L.; Wu, W.; Yan, J.; Liu, Y. Urbanization for rural sustainability—Rethinking China’s urbanization strategy. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 178, 580–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, P.; Sliuzas, R.; Geertman, S. The development and redevelopment of urban villages in Shenzhen. Habitat Int. 2011, 35, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, G. Decline and revitalization of countryside. Planners 2016, 32, 142–147. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Transforming Our world: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 1 May 2021).

- Zhou, Z.H.; Zhang, J.X.; Chen, J.C. Governance of persuasion: A logical interpretation of rural governance based on communication action theory. Urban Dev. Stud. 2021, 28, 45–52. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yao, H.; Shen, L.; Tan, Y.; Hao, J. Simulating the impacts of policy scenarios on the sustainability performance of infrastructure projects. Autom. Constr. 2011, 20, 1060–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.D.; Shen, M.R. Ecological transformation of small towns in Yangtze river delta: A case study of Gaochun, Nanjing. Urban Rural Plan. 2018, 2, 106–112. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doh, M. Change through Tourism: Redident Perceptions of Tourism Development. Ph.D. Thesis, Texas A & M University, College Station, TX, USA, 2006; p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, J.; Wu, B. Revitalizing traditional villages through rural tourism: A case study of Yuanjia Village, Shaanxi Province, China. Tour. Manag. 2017, 63, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, X.; Lin, J.; Li, Y. Beyond government-led or community-based: Exploring the governance structure and operating models for reconstructing China’s hollowed villages. J. Rural Stud. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Fan, P.; Liu, Y. What makes better village development in traditional agricultural areas of China? Evidence from long-term observation of typical villages. Habitat Int. 2019, 83, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habiyaremye, A.; Kruss, G.; Booyens, I. Innovation for inclusive rural transformation: The role of the state. Innov. Dev. 2020, 10, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Cheng, L.; Iqbal, J.; Cheng, D. An integrated rural development mode based on a tourism-oriented approach: Exploring the beautiful village project in China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban-Rural Land Linkages: A Concept and Framework for Action. Available online: https://gltn.net/download/urban-rural-land-linkages-a-concept-and-framework-for-action/?wpdmdl=17174&ind=1624017896178 (accessed on 1 June 2021).

- Magel, H. Marrakech declaration. Urban-rural-interrelationship for sustainable development. In Proceedings of the 2nd FIG Regional Conference, Marrakech, Morocco, 2 December 2003; ISBN 8790907329. [Google Scholar]

- Eom, S.; Rhee, S.; Kim, H.; Kim, M. Director opinion on community competence: Evidence from management organizations of the rural community support project in South Korea. Agriculture 2020, 10, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez de Andrés, E.; Cabrera, C.; Smith, H. Resistance as resilience: A comparative analysis of state-community conflicts around self-built housing in Spain, Senegal and Argentina. Habitat Int. 2019, 86, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böcher, M. Regional governance and rural development in Germany: The implementation of LEADER+. Sociol. Rural. 2008, 48, 372–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aina, Y.A.; Wafer, A.; Ahmed, F.; Alshuwaikhat, H.M. Top-down sustainable urban development? Urban governance transformation in Saudi Arabia. Cities 2019, 90, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, C.; Deng, X.; Dong, J.; Hu, P. Urbanization and sustainability: Comparison of the processes in “BIC” countries. Sustainability 2016, 8, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Németh, J.; Langhorst, J. Rethinking urban transformation: Temporary uses for vacant land. Cities 2014, 40, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, C. Towards a meta-framework of endogenous development: Repertoires, paths, democracy and rights. Sociol. Rural. 1999, 39, 522–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M. Rural Revitalization through State-Led Programs; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2020; ISBN 978-981-15-1659-7. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, L.J.C. The great urban transformation: Politics of land and property in China. Reg. Stud. 2010, 44, 1099–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Long, H.; Liu, Y. Spatio-temporal pattern of China’s rural development: A rurality index perspective. J. Rural Stud. 2015, 38, 12–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Fan, S.; Zhang, L.; Huang, J. Local governance and public goods provision in rural China. J. Public Econ. 2004, 88, 2857–2871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, M. Rural geography: Blurring boundaries and making connections. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2009, 33, 849–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, M. Engaging the global countryside: Globalization, hybridity and the reconstitution of rural place. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2007, 31, 485–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Sun, X.; Sun, L.; Choguill, C.L. Optimizing the governance model of urban villages based on integration of inclusiveness and urban service boundary (USB): A Chinese case study. Cities 2020, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, W.; Chen, T.; Li, X. A new style of urbanization in China: Transformation of urban rural communities. Habitat Int. 2016, 55, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, P.; Chen, J.; Gao, J.; Li, M.; Wang, J. What role(s) do village committees play in the withdrawal from rural homesteads? Evidence from Sichuan province in western China. Land 2020, 9, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Woods, M.; Chen, J.; Liu, Y.; Gao, J. Globalization, state intervention, local action and rural locality reconstitution—A case study from rural China. Habitat Int. 2019, 93, 102052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, J.R. People and plans in urbanising China: Challenging the top-down orthodoxy. Urban Stud. 2018, 55, 1375–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.L.; Liu, Y.T. Rural governance under the mutual assistance of village working team and rural elite. Hum. Geogr. 2020, 2398, 23–31. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, Y. In search of open and inclusive arenas: Transnational practice of communicative planning in Yongtai, China. Habitat Int. 2020, 106, 102288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, D.A. Chinese NGOs at the interface between governmentality and local society: An actor-oriented perspective. China Inf. 2020, 35, 158–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homsy, G.C.; Liu, Z.; Warner, M.E. Multilevel governance: Framing the integration of top-down and bottom-up policymaking. Int. J. Public Adm. 2019, 42, 572–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanssen, G.S.; Nergaard, E.; Pierre, J.; Skaalholt, A. Multi-level governance of regional economic development in Norway and Sweden: Too much or too little top-down control? Urban Res. Pract. 2011, 4, 38–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building theories from case study research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morland, J.K.; Feagin, J.R.; Orum, A.M.; Sjoberg, G. A case for the case study. Soc. Forces 1992, 71, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Long, H.; Cui, W. Community-based rural residential land consolidation and allocation can help to revitalize hollowed villages in traditional agricultural areas of China: Evidence from Dancheng County, Henan Province. Land Use Policy 2014, 39, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.R.; Shen, J.F. Evaluating the cooperative and family farm programs in China: A rural governance perspective. Land Use Policy 2018, 79, 240–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Westlund, H.; Zheng, X.Y.; Liu, Y.S. Bottom-up initiatives and revival in the face of rural decline: Case studies from China and Sweden. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 47, 506–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, O.E. Public and private bureaucracies: A transaction cost economics perspective. J. Law Econ. Organ. 1999, 15, 306–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, O.E. The new institutional economics: Taking stock, looking ahead. J. Econ. Lit. 2000, 38, 595–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Li, R.; Zhang, L.; Jing, Y. Spatially illustrating leisure agriculture: Empirical evidence from picking orchards in China. Land 2021, 10, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).