Abstract

Tourists from different cultural backgrounds have different perceptions of the image of a tourist destination. This paper aims to investigate tourist destination image (TDI) from a national cultural perspective and to see whether there exists the influence of culture on a visitor segment’s destination image as well as their travel behavior and satisfaction. Barcelona as the destination and the Chinese market are utilized to present an empirical discussion of the study. Based on the results of the qualitative method previously conducted by the authors, a questionnaire was designed in this paper. The SPSS 22 program was used for data management and analysis. This study first demonstrates that TDI perceived by the Chinese visitors is influenced by their pro-social cultural background and, second, that the visitors greatly value prestige and social networking during the visitation. This study further discusses the reasons why the visitors greatly value prestige and social networking and how “facework” influences their travel behavior based on the concept of culture value orientation. Overall, this study contributes to the existing knowledge on the formation of perception of TDI by analyzing the influence of the tourist cultural background on their TDI.

1. Introduction

Tourist destination image (TDI) has been studied as a core part of tourism marketing. It plays a significant role in differentiating the destination from others and tourist destination market positioning [1,2]. Tourists’ holiday choice decisions are frequently based on TDI. After visiting the city, their impressions of the destination determine if they will revisit it, and their opinions passed on by word of mouth affect other potential tourists’ travel decisions. Therefore, studies on TDI and understanding what determines tourists’ TDI formation are never outdated in the academic field [3]. With the development of research in related fields, new emerging factors that affect TDI formation should be taken into account. For instance, tourists from different cultures have different perceptions and impressions of the destination [4,5,6,7]. The relationship between the tourists’ cultural background and their perceptions of the destination is necessary to consider in an analysis of tourism.

Edward Tylor (1871) defined culture as the ‘complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, custom, and other capabilities acquired by man as a member of society’ [8]. In the early 20th century, American anthropologist Franz Boas redefined that culture as “a combination of beliefs, customs, and social systems used to distinguish different social groups.” [9]. As Reisinger and Turner (2002) concluded, culture teaches people how to perceive experiences and interpret meanings [5]. Since then, tourism researchers have begun to attach importance to cross-cultural research regarding tourists’ perceptions. Related studies have shown that culture is an important factor affecting tourists’ perceptions. Tourists with different cultural backgrounds have different travel preferences and behaviors [10]. Some cultures share similarities based on their value systems [7], such as East Asian countries (e.g., China, Japan and Korea), which share Confucian values, and the people from there are more collectivistic. In this paper, the concept of face culture and its application in a collective-orientated society that emphasizes harmonious relationships, and the concept of Chinese tourism will be discussed.

A large number of scales of TDI measurement have been developed by previous scholars. These scales were originally created using Western tourist samples who visited Western destinations [3,11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. Despite the continuous improvements to these scales and the fact that they have been used to measure various samples, with modifications made to consider the differences in tourist destinations, relatively little TDI research has been studied from the perspective of Chinese tourists in a Western destination. Previous studies on TDI from the eyes of different nationalities/regions have demonstrated that cultural differences exist in terms of travel motivations, travel behavior and satisfaction [1,2,4,5,10]. Moreover, it is important to clarify that Chinese tourists represent a cross-cultural setting that is significantly different from the Western context [7]. Tian and Cànoves (2020) developed a scale measuring TDI that can account for a Chinese tourist sample in a Western destination by approaching a qualitative method with participant observations and unstructured interviews [18]. The purpose of the study presented here is to continuously examine and develop the TDI measurement scale among the Chinese tourists with the quantitative method utilized by Tian et al. We expect our findings of this investigation to enhance our understanding of how and why perceptions of a Western tourist destination city’s image vary in the eyes of the tourists with an East Asian cultural background.

2. Literature Review and Background to the Study

2.1. Tourist Destination Image

Hunt defined the concept of TDI as early as 1971, and until now research in this area has continued nonstop [11]. The latest guidelines for tourism admit that the development of TDI is based on the tourists’ rationality and emotionality, and as the result of the combination of two main components or dimensions: the perceptive/cognitive component, which refers to the individual’s own knowledge and beliefs about the destination, reflecting evaluations of perceived attributes of the destination, and the affective component echoing tourists’ feelings towards the destination [12,13,19]. From a visual point of view, a city’s tourism image is a logo, and a city should use unique logos and graphic symbols (such as patterns, emblems, etc.) to ensure that people can quickly identify and recognize its tourism image [20]. For instance, Spain’s tourism logo, designed by Catalan artist Joan Miro, is a red, black, and yellow sun. Some people thought it looked like a fried egg, but actually it is simple, attractive, and impressive to the world. When the government launched their campaign with this logo in 1984, it was a huge success [21]. From the view of city tourism, TDI is the general term for the characteristics of city tourism products and services, which are different from other competitive tourist destinations [22,23,24]. TDI is a summary of the comprehensive connotations of city tourism with a certain degree of popularity and reputation. From the public’s point of view, TDI represents the experience and evaluation of the city’s tourism products, service quality and overall strength [22].

In the topic of TDI formation, two approaches to its process are considered: static and dynamic formations [14]. The static formation process refers to the relationship between image and the tourist’s attitude such as satisfaction and destination option. The majority of previous studies regarding TDI formation have been based on the concept of either two or three main components of TDI: cognitive, affective and conative [12,13,15]. The cognitive component concerns the sum of what is acknowledged about a destination; the affective refers to the visitors’ feelings to the destination; the conative is the likelihood of an intention to visit a destination within a certain period that emerges from the first and second components [12,13]. As this present study does not focus on the action after the assessment of the first and second dimensions, only the cognitive and affective dimensions are considered as components of the TDI formation model in this study. Regarding dynamic formation, the importance of TDI in its entirety is stressed [14]. Gunn’s (1972) seven-stage theory is a useful interpretation of the dynamic feature [16].

In this paper, static formation will be analyzed. Regarding the static formation measurement, studies in the early 21st century created sets of factors that have a similar grouping of variables that refer to the nature of the tourist destination, such as “sun and sand”, “natural environment”, “attractions” and others [13,17,25]; Stylos and Andronikidis’s (2013) TDI static formation measurement corresponds to tourists’ involvement with the tourism destination [26]. Martin and Bosque (2008) analyzed the relationship between psychological factors and the perceived image of a destination to argue that TDI should be considered as a multidimensional phenomenon that includes not only beliefs or knowledge about the place’s attributes, but also the individual’s feelings toward the destination [27]. In this regard, numerous researchers across fields and disciplines agree that image is mainly caused by two major forces: personal/internal factors (social and psychological characteristics of the perceiver, e.g., values, motivations, and level of education), and external stimulus factors (e.g., information sources and previous tourist experience) [12]. Among these factors, tourism motivation has a significant impact on their affective evaluation of TDI [13,17]. Based on the conclusion of the statistically significant positive impact of TDI on the formation of attachment values to a place, Veasna, Wu, and Huang (2013) confirmed that there is a relationship between image and tourist subsequent satisfaction [28,29]. With reference to this literature, one consideration is obvious: it tends to be studied from the perspective of Western culture [29].

Regarding the issue of Chinese tourists visiting Spain, especially Chinese tourists’ impressions about Spain, there were few studies outside of reports published by the Spanish authorities before 2010. “An assessment of Plan China” [30] indicated that Spain, to a negligible extent, does not have a prominent presence in Chinese tourist motivations or culture. Otero (2008) indicated that the image of Spain that is found in China is a stereotypical image, dominated by bullfighting and sport [31]. Two out of three Chinese people are unable to name a popular Spanish historical or fictional character. During the past 10 years, research on Chinese tourism in Spain has received more attention [32,33,34,35]. In terms of Chinese visitors’ perceptions of Spain, Lojo (2016) indicated that travel agencies highlight the distinctive elements of Spain through their tourism products to attempt to create an image of Spain, such as its history and artistic culture, the iconic modernist architecture, Spanish cuisine and so on [33]. With respect to Chinese tourists visiting Barcelona, there is little information documented by the main authorities that collect such data. The corresponding research gathered outside of formal reports [36,37,38], especially Chinese visitors’ impressions about Barcelona as a tourist destination, include a study of the components of Barcelona’s TDI in the Chinese market using the qualitative method [18] that was mentioned in the introduction, and studies of Chinese tourism in Barcelona addressing how Barcelona is perceived as a tourism destination generally [39,40].

2.2. Different Cultural Background’s Perception of TDI

“The manner in which people view images of a destination is mediated by cultural background”, because the influence of the differential value structures (for instance: Hofstede’s culture dimensions) “is expressed through lifestyle, work, leisure, and consumer behavior patterns” [41,42] (p. 417). National cultures do affect tourists’ decision-making, behaviors, and satisfaction with the destination [7,43]

2.2.1. Culture Value Orientation: Collective Orientation in China

The cultural values of each nationality orientate one group of tourists in terms of their perceptions of the destination they visit [1,44]. Cultural value orientation (CVO) is indicated to distinguish the perception of one destination, tourist attitudes towards it, and their travel behavior among different groups of tourists [44].

Different countries have different cultural systems [45]. Culture is defined as “the collective programming of the mind that distinguishes the members of one group or category of people from others” [45] (p. 4). Culture influences people the way they perceive information and experiences [5].

Culture has its value. Value is defined as “conception, explicit or implicit, distinctive of an individual or characteristic of a group, of the desirable which influences the selection from available modes, means and ends of action” [44] (p. 395). Value affects the decisions and behavior patterns of individuals or groups.

Different value orientations represent different value positions and value attitudes. Value orientation is the core element of the pro-social behavior-oriented system and the personality structure related to interpersonal [46]. Li and Sun’s (2001) research demonstrated that the stronger the collective orientation of an individual, the more likely the individual is to engage in pro-social behavior; conversely, the stronger the individual orientation, the less likely the individual is to engage in pro-social behavior [46]. Collectively oriented people often consider their own influence on others and value harmonious interpersonal relationships while protecting their own image.

Chinese people operate in a collectively orientated manner and adapt these values into their life [47]. Yang (2004) divides collective orientation into four categories, namely family orientation, relationship orientation, authority orientation and others orientation [47]. Yang (2004) believes that within the family orientation of traditional Chinese society, Chinese people tend to emphasize an individual accommodating to the collective, which is a kind of familial collectivism [47]. The relationship orientation is the main mode of operation of Chinese people in the network of interpersonal relationships. Traditional Chinese culture emphasizes the definition of one’s own identity in terms of the social relationship between people, and even their advantages. In order to maintain the harmony of the relationship, individuals must strive to do what the other party expects and also try to protect the face of others and avoid possible conflict. In this way, an orientation toward authority is a relevant traditional continuation of Chinese people’s respect for the upper and lower relations. The others orientation means that Chinese people are easily influenced and affected by others in their psychological and behavioral aspects. They are particularly sensitive and value others’ opinions, standards, praise, and criticism. As such, it can be said that they hope to leave a good impression in the minds of others and try to be consistent with others in their behavior. The others orientation means that Chinese people think about the meaning of others, obey and take care of others, pay attention to norms, and value reputation, so as to make people feel that the person knows how to behave well and get along with people quite well, and is a person with a good image (face), the concept of which will be further explained in Section 2.2.3.

According to all the characteristics mentioned in the four categories of collective orientation, we can observe that, if an individual wants to integrate into a pro-social society, especially a society such as China, with a large population and large family dynamics, the operation of relationships in different categories of collective orientation is crucial.

2.2.2. Harmonious Relationships

Confucius’ legacy has influenced Chinese society for thousands of years, and Confucianism focuses on the morality and ideals of human relationships. There are five key relationships within Confucianism: 1. ruler and subject; 2. father and son; 3. elder brother and younger brother; 4. husband and wife; 5. friend and friend. The fifth dynamic is the only the relationship that does not establish an authority orientation and can be better understood as a “relational position” (Chinese pinyin: renlun). While maintaining these relationships, Chinese people subconsciously use the four orientations mentioned above as their mode of operation.

No matter what kind of relationship, “one’s ability to achieve a harmonious relationship with others is the greatest spiritual accomplishment of one’s life” [48] (p. 105). Harmony is an important concept of Chinese traditional culture. The three schools of Confucianism, Buddhism and Taoism, which constitute the backbone of traditional Chinese culture, have profoundly elucidated the concept of harmony, and they all regard harmony as an important value orientation. They explain harmony as: (1) seeking harmony in the relationship between people’s body and mind, and it is advocated to strengthen the recuperation and realize the harmony of self and body. In psychology, it is mostly called “self consistency and congruence”; (2) advocating “seeking common ground while reserving differences” in the relationship between people—that is, to achieve unity and harmony on the basis of maintaining differences; (3) advocating fairness and equality in the relationship between people and society, seeking to establish a harmonious society in which everyone gets what they want; (4) seeking harmony between people and the nature. Due to the context of this study, this paper focuses more on the relationships between people, people and society, and the relationship between an individual’s body and mind.

Rogers (1959) argued that every individual has a real self (how the person really is) and an ideal self (how the person would like to be) [49]. If there exists a discrepancy between an individual’s ideal-self and their experiences in reality (real-self), it means that there is a gap between the two selves. “The closer the person’s self-image and self-ideal are each other, the more congruent or consistent and the higher person’s sense of self-worth” [49]. If, in the real experience, a person does not present the ideal self, the person may think that this is a loss of self-image and would look for a way to make up the gap. One method is to try to improve one’s own ability level to make up for this missing image (real face—shimianzi); another method is to make up for the discrepancy by modifying one’s external image, showing illusions and behaviors that are better than the actual ability to make up for the lack thereof (virtual image—xumianzi) [50]. For instance, visiting famous tourist attractions and taking a selfie and posting it to the social media, or buying luxury goods to “package” themselves (Myers, 2016) are actions involved in this process. Here, the concept of “face” arises.

2.2.3. “Face” and “Facework” in Relationships

Regarding an individual’s self-image, in Chinese it is colloquially called “mianzi”, which is “face” in English. This colloquial name has been used as a term in the academic field. The Chinese saying that a person needs face like a tree needs bark indicates the importance of face to participate in Chinese society [51,52,53]. As early as 1890, Smith said that in the Qing Dynasty in China, “Once rightly apprehended, “face” will be found to be in itself a key to the combination lock of many of the most important characteristics of the Chinese” [54] (p. 16).

In this context, face does not mean a person’s physical body part, but refers to a person’s public self-image. It recognizes an individual’s social position and prestige as well as the projection of one’s self-image within one’s social network—“public self-image” [52,55,56]. It is an evaluation of a person regarding status within a social structure [54,57]. Correspondingly, there is the concept of “facework”, which describes the maintenance of one’s perceived image, including face-saving (aimianzi), face-building (zuomianzi), face-borrowing (jiemianzi), face-having (youmianzi), face-giving (geimianzi) and many other behaviors [52,55,56,58,59].

In China, face-saving (aimianzi) is considered a natural thing, since getting recognition and praise from others is a basic social need and has psychological appeal in the pro-social country [57]. Confucianism encourages Chinese people to value face for largely moral reasons [48,60]. However, nowadays, Chinese people are encouraged to focus on “facework” for not only moral but also for instrumental reasons, such as obtaining relatively high social status, power, prestige, favor (renqing), mutual obligations, reciprocity (bao) and influence in relationships [61].

Gaining a good “face” for the self is part of seeking harmony in the relationship between a person’s body and mind; however, it is also an important part of seeking harmony in the relationship between people and between people and society. Facework is applied to the aspects of the individual’s own reputation, the maintenance of friendships, family relationships and work partnerships. It can also be represented in their travels.

In short, in order to achieve harmonious relationships and a harmonious society, the propriety or etiquette (li), proper emotion (renqing), the relational position (renlun) and the fame (ming) should be governed very well. Subsequently, face is a goal and a means to achieve ideal personhood [50,51,52,62]. Face is a social extension of personal ethics (propriety) in the Confucian system. With all these culture-related factors, Chinese tourists visually and physically are in another country, but they are actually in a liminal stage of the tourist experience, which means that mentally they do not integrate into the local culture, and they still adhere to the cultural values of their home society.

According to all the statements made, we formulated the following hypothesis: the cultural background of the collective value orientation of Chinese tourists will affect their perception of a Western tourist destination’s image, travel motivation, satisfaction and even their travel behavior. Thus, this study aims to substantiate the mentioned hypothesis and analyze how their home society CVO influences their perception and explain the reasons for this through a case study of Barcelona, Spain.

2.3. Background to the Study

2.3.1. Tourism in Spain and Barcelona

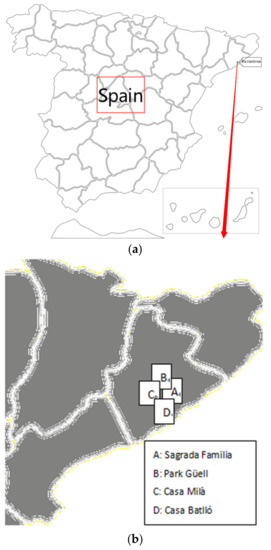

Compared to the tourism situation of other European countries, Spain’s annual number of international tourists is at an upper middle level (Table 1). Barcelona, as the selected study site (Figure 1), is one of the world’s leading tourist destinations. It is a coastal city, located in the northeast of Spain, with a very advantageous geographical location and a pleasant climate. In 2019, Barcelona received nearly 12 million tourists, 5% more than the previous year, who made about 33 million overnight stays (an increase of 5.6%) [63].

Table 1.

Chinese tourist arrivals in European countries.

Figure 1.

(a) Barcelona on the map of Spain. Source: authors’ own preparation. (b) Map of Barcelona and its top cultural locations. Source: own preparation.

The 1992 Olympic Games, held in Barcelona, as indicated on the map, enabled the city to expand its tourist capacity and led to it becoming one of Europe’s main tourist destinations [64]. In the late 20th century, the city received labels such as “sun, sand and sex”, which attracted many tourists with motives to visit sun and sand destinations, but most of these tourists were Western visitors [64,65]. From 2000 to 2019, before the pandemic, the numbers of tourist arrivals and overnight tourist stays in Catalonia and Barcelona recorded constant growth due to the numerous tourism activities [66]. Among them, the sun and sand tourism model has generated more than half the tourism demand in Catalonia, but “it is not competitive enough in terms of quality” and has increasingly affected local people’s daily life [67]. Over the last decade, Barcelona has been suffering the growing symptoms of overtourism, which caused the phenomenon of tourismphobia. This issue is directly related to unsustainable mass tourism. One of the Barcelona government’s actions to combat this was to promote its “high” culture, including its architects and their Modernist architecture, instead of sun and sand tourism. As early as the beginning of the 21st century, Barcelona attempted to establish the city as a cultural destination with a series of cultural theme years, including the Miro Year, the Gaudi Year, the Design Year, and the Dali Year [68]. Currently, the “2018–2022 Strategic Tourism Plan for Catalonia” and “Strategic Tourism Plan 2020” for Barcelona still consider the compatibility of growth in tourism with preserving the quality of life of its citizens as one of the main goals, and that leading tourist destinations should strategically promote the extraordinary quality of their natural and cultural landscapes to roll out a sustainable prosperity model [69,70,71].

Due to the tourist crisis caused by the pandemic, overtourism is not an issue temporarily. In order to overcome the post-COVID-19 tourist crisis and at the same time to maintain the sustainable coexistence between the visitors and the inhabitants [72,73,74], Barcelona is still committed to promoting its culture (in the broad sense, such as architecture, art, design, and literature, among others). Therefore, Barcelona prefers visitors that are genuinely interested in the city, and value customers who are sustainable and respectful of the destination. One of their niche target groups is tourists from Southeast Asia [75].

According to the interviews conducted in the research of Tian and Cànoves (2020), Sagrada Familia and Park Güell, Casa Milà and Casa Batlló (see their locations in Barcelona: Figure 1), architecture designed by Gaudí, are undoubtedly the favorite examples of cultural heritage among Chinese tourists [18]. Other cultural landscapes, such as Barrio Gótico and La Rambla, are also very attractive to them. Therefore, they could be considered as part of tourism marketing for the Chinese tourists.

2.3.2. Chinese Tourism in Spain and Barcelona and the Schengen Visa

“Filled by its growing middle class and rising spending power” [18] (p. 138), China’s travel has shown a strong increasing trend of outbound tourism. As 2021 and 2022 are considered crucial years for a possible tourism recovery after the pandemic, the statistical results of Chinese outbound tourism in 2019 offers a useful reference. In the year 2019, China’s outbound tourist arrivals totaled 155 million [76]. In the same year, 6.3 million Chinese tourists visited Central/Eastern Europe [76], but only 869,000 of them visited Spain, contributing EUR 1.675 million a year to Spain’s tourism industry.

Attracting Chinese tourists has always been a strong desire of the Spanish tourism industry. As early as 2011, the Spanish government issued “Plan Turismo China” [77]. One of the goals of this initiative was to receive 1 million Chinese tourists every year after 2020. However, so far, Spain’s efforts in attracting Chinese tourists have had very underwhelming results. For instance, France and Italy, which also belong to the Latin cultural circle, have been more attractive options to Chinese tourists in comparison to Spain. The French region of Île-de-France received 950,000 Chinese tourists in 2019. In 2018, France received approximately 89.4 million foreign tourists, including 2.2 million Chinese tourists; in the same year, Italy also received about 2 million Chinese tourists [78].

Some Chinese tourists say that they do not choose to travel to Spain because of the slow visa processing speed [79]. The Schengen visa is undoubtedly one of the best and most famous visas in the world: the visa holder has the possibility to travel to 26 European countries. However, many Chinese tourists still complain about the slow processing speed of Spanish visas [79]. There are uniform regulations of visa requirements for Schengen member states, but different countries still have different additional requirements, and the processing time is also different [80]. Starting from February 2020, the Schengen visa rules have changed, including reducing the visa processing time and accepting electronic applications [81]. These changes will help Spain to attract Chinese tourists; however, as a tourist destination, the key point for Spain is to find the correct image positioning in the Chinese market. This becomes clear in discussing countries like France, Italy, and Germany. When we talk about France, we think of romance [82]. When we talk about Italy [83], we think of art. In Germany, we think of precise technology and high-quality products [84]. In general, Barcelona or Spain is famous for sun and beach tourism among Western countries; however, this part of Barcelona is not as attractive to tourists from East Asia. Therefore, to find a precise positioning in the Chinese market, we must first deeply understand how the Chinese cultural background affects their perception of a Western city’s image.

3. Methods

This study utilized a mixed methodology. On the basis of the qualitative method conducted in Tian et al.’s paper [18], and Barcelona’s TDI measurement scale for Chinese tourists created in the same paper, a questionnaire was designed in this study.

Why was a mixed method of qualitative and quantitative research used? Considering this question from the dialectical perspective, the unity of the two methods is a better approach for our study. This is because, in view of the fact that there is no universal scale for Barcelona’s TDI in the Chinese tourists’ eyes, Tian et al.’s (2020) study constructed the content of the scale based on the fieldwork and interviews (qualitative research), and combined the existing literature review to generate the scale indicators [18]. This is a “bottom-up” approach to develop measurement scale for the project. Additionally, to obtain an accurate and scientific understanding of it, the relationship between components of Barcelona’s TDI was analyzed. Therefore, quantitative research was conducted.

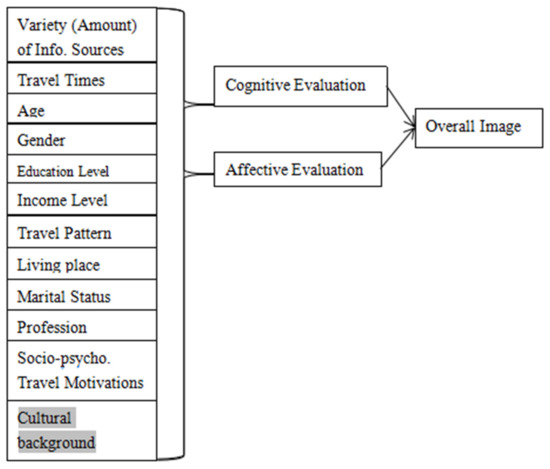

Data Collection

Based on the model of formation of TDI according to the literature review [13,17], and qualitative research [18], the initial components of Barcelona’s TDI in the Chinese market were obtained: cognitive evaluation included the categories of social and natural environment, the city’s atmosphere, and the tourism atmosphere; the influencing factor of travel motivations consists of the categories of absorbing knowledge, seeking prestige and relaxation; the affective evaluation and the overall TDI do not have categories. A path model of the relationships between the determinants was obtained as well (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Path model of determinants of the study. Source: own preparation based on the models of Baloglu and Mccleary (1999) and Beerli and Martin (2004) [13,17]. Note: the attribute in gray denotes that it is examined and analyzed in this paper.

After the specialist evaluation method was used with one tourism destination management expert, one tourism market operator and one travel route designer to evaluate the content validity of the surveyed items, and after 10 Chinese travelers were invited to fill the pilot questionnaire, the initial 41 measurement scale items were obtained. In order to better understand the common features between different items, they were also preliminarily classified. The cognitive evaluation category of the social and natural environment includes eight items (service quality, good weather, friendly local people, personal safety, travel information, Mandarin information, shopping service, and accommodation service); the cognitive evaluation category of the city’s atmosphere consists of five items (exciting, happy, curious, relaxing city and cosmopolitan city); the cognitive evaluation category of tourism attractions includes seven items (1992 Olympic Games stadium, Camp Nou of Barça, shopping points, cultural attractions, heritage attractions, sun and beach, Gaudi’s architecture). Regarding the factor of travel motivations, the category of absorbing knowledge obtains three items (to feel exotic atmosphere, to discover occidental culture, heritage); the category of seeking prestige consists of four items (experience, good shopping resources, social networking and increasing social level); the category of seeking relaxation includes six items (leisure, good place to travel with friends and relatives, safe and quiet, seeking good weather and escaping smog, to participate in sun and beach tourism that I have not experienced abroad, good natural landscape). The affective evaluation includes the following four items: pleasant, excited, relaxed, and curious. Overall, Barcelona’s TDI has four items, which are rich heritage, high service quality, kind local people and a cosmopolitan atmosphere. The final determinant factors and variables will be identified after principal component analysis in SPSS.

After the same specialist evaluation method was used, 58 questions for the questionnaire were obtained. The questionnaire consisted of two sections. The first sections included the sociodemographic profile of the respondents, their travel frequencies to Europe, to Spain and to Barcelona, and their current travel pattern to Barcelona. The second section collected travel motivations to visit Barcelona and their satisfaction with the trip and the city as a tourist destination, including the cognitive and affective attributes. For this part, a 5-point Likert scale was used to measure the importance of each item, with 1 being not important at all and 5 being extremely important.

In the beginning, the questionnaire was conducted through offline distribution; however, we did not obtain the quantity of samples that we expected. Afterwards, the questionnaire was carried out via Wechat, where we obtained a sufficient quantity of samples. One of the authors is originally from China and has been living in Barcelona for almost 10 years, so this author knew how to conduct the survey using Wechat and had a vast number of contacts from Wechat that matched the profiles of the study’s targets, namely Chinese tourists that had visited Barcelona. The author sent the questionnaire to all the Wechat groups that met the requirements. Additionally, a survey using the snowball method was conducted via Wechat. In order to achieve the same quality as the offline questionnaire survey, each group had a group leader who took charge of answering questions from the group members when they filled in the questionnaire. Data for the study were gathered online from 20 December 2016 to 10 January 2017. Eventually, 403 responses were collected online, and the data collected via offline sources were discarded. First, we removed the surveys with invalid responses and those that did not pass the screening questions. In the remaining questionnaires, if the missing value of each variable was less than 10% of the total number of the results [85], we used the SPSS 22 to add the missing value, resulting in 370 valid questionnaires obtained for the study. It is worth mentioning that 2020 was affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, and outbound Chinese tourism was thus severely reduced during this year. This study was conducted before 2020, so the results presented in the following section cannot represent recent Chinese tourism.

4. Results

4.1. Sample Profile

Eleven sociodemographic variables were analyzed. The sample of 370 valid questionnaires was composed of, to some extent, a large difference in the percentages of men and women (119 males, 32.3% and 251 females, 67.8%). According to the “Big Data Report of Outbound Tourism” published by China Tourism Academy in 2018, Chinese women like to travel abroad more than Chinese men. Another fact is that a larger percentage of female respondents returned surveys than male respondents, and women are perhaps relatively more likely to spend time filling out questionnaires than men [86].

The power of youth travel cannot be ignored. As Table 2 shows, the majority of the respondents were young people, between 18 and 29 years of age (217 visitors, 58.6%), and they are from a relatively well-off and educated stratum of society that can be considered as the Chinese middle (higher) class. Regarding the travel pattern, the majority of the Chinese visitors in Barcelona were independent tourists (310 independent visitors out of the total 370 respondents, 83.8%), which consist mostly of young people, while comparatively, most group visitors were more than 50 years old.

Table 2.

Most frequency characteristics of the respondents.

It is also worth mentioning the comparison of different travel experiences. In total, 67.8% of visitors were first time travelers to Spain, but 50.3% of tourists were already on their third visit to Europe. We can observe that Barcelona was not one of their top European destinations to visit. We list all the largest proportions of each item from the sociodemographic and travel-related characteristics of the survey in Table 2.

Given the closeness of many of the TDI attributes mentioned previously, and to provide more meaningful analysis, in every group of attributes, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted, with principal components analysis (PCA) and Varimax rotation, with the aim of reducing their dimensions and identifying the determinant factors. At the same time, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were calculated to test the consistency of the factors. The EFA was based on the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sample adequacy (0.80) and Bartlett’s test of sphericity with its significance level (p < 0.000).

After the PCA using SPSS 22, among the original items that were collected from the literature reviews, interviews and specialist evaluation, the rotated factor loadings of “relaxing”, “personal safety”, “shopping service”, “accommodation service”, “nature/sun and beach” and “Gaudi’s architecture” on the five factors are less than 0.5, which means that they cannot effectively represent the contents of the five factors; in other words, they did not correlate with any other variables at any level, so these items were omitted. The item “Gaudi’s architecture” was omitted. This could be the consequence of its overlapping meaning with the item of “heritage architecture”. However, the item of “shopping points” was kept, because its rotated factor loading (0.631) is higher than 0.5 for the factor of tourism attractions, and it belongs to the factor of “tourism attractions”. Eventually, we obtained a total of 14 items from five factors of cognitive image and four items from one factor of affective image (Table 3).

Table 3.

Principal component analysis of cognitive and affective evaluations.

Cognitive image: The first factor, found to be “the social and natural environment”, was labeled as COG1, as it consists of different kinds of social environment such as the cosmopolitan city, service quality, good weather and friendly local people. The second factor, service and information, was labeled as COG2, which includes items related to travel information and Mandarin information. Factor 3, atmosphere, was labeled as COG3, which relates to feelings regarding travel status, such as exciting, happy and curious and fresh. Factor 4 refers to tourist hot spots, labeled as COG4, and contains attributes related to Olympic games’ hot spots, Camp Nou (Barça) and shopping points. Factor 5 represents cultural sites labeled as COG5, which relates to Barcelona’s heritage architecture and its cultural attractions.

It is worth mentioning that here, five factors are derived from quantitative research, while the original three dimensions (social natural environment, city’s atmosphere and tourism attractions) were derived from the qualitative method before. After the PCA in SPSS, the original factor of “social and natural environment” with eight items was divided into COG1 and COG2: COG1 retains three of the eight original items and one new item of “cosmopolitan city”, which was initially from the factor of “city’s atmosphere”, and the expression of “cosmopolitan city” was changed to “cosmopolitan environment”; COG2 (service and information) retains two original items (travel information and Mandarin information). COG3 (city’s atmosphere) retains three of the five original items. The initial factor of “tourism attraction” was divided into two factors, which are subsequently COG4 (tourism attractions) and COG5 (cultural sites). COG4 retains three of the original seven items, and the original “cultural attractions” and “heritage attractions” are finally divided into the subsequent COG5. In short, the PCA analysis further subdivided the three dimensions obtained from the qualitative research analysis into five dimensions, which shows that the dimensions obtained by the qualitative research are relatively broad and general, and the meanings of the variables in some of the dimensions are quite different. The five subdivided dimensions after PCA analysis make subsequent data analysis more convenient.

As illustrated in Table 3, affective image, labeled as AFF, has four items from the factor. According to the four semantic differentials scales, developed by Russel and Pratt (1980) [87], there are the dimensions of relaxing/distressing, arousing/boring, exciting/gloomy and pleasant/unpleasant. In our study, we modified the translation of “arousing” to “curious”, taking into account tourism-related professionals’ advice that suggests that this makes it easier for respondents to understand, especially if it is translated into Chinese.

The Cronbach alpha values reported for COG2 and COG5 are low. This could be a consequence of these two factors comprising only two items and Cronbach’s alpha being sensitive to the number of items in a scale. However, it was considered suitable to maintain the two items in each factor so that the scale would be coherent with the dimensions and attributes that we obtained through the interviews with experts in related fields.

As Table 4 shows, the PCA was applied to the attributes of Chinese tourists’ motivations to travel and generated four factors which were labeled MOT1, MOT2, MOT3 and MOT4. MOT1 consists of items related to cultural experience: to have more experiences, to feel an exotic atmosphere, to learn more about occidental culture, to learn more about Spain’s heritage and to learn more about occidental leisure culture. The second factor relates to relaxation, considering attributes such as many shopping resources, good city to travel with friends and safe and quiet. MOT3 includes items related to prestige and networking: to have more social networking, and to improve social level. In order to obtain a higher Cronbach’s alpha value (0.721), in the end, the attribute of “to visit friends/relatives” was omitted. Finally, MOT4, “search for natural beauty”, considers the attributes of seeking good weather and escaping smog, participating in sun and beach tourism not experienced abroad, and good natural resources. Regarding the PCA of overall TDI, the only factor, labeled OTDI, was obtained by omitting one attribute, namely “rich heritage”, which did not correlate with any other variables.

Table 4.

Principal component analysis of travel motivations and overall TDI.

4.2. Chinese Tourists’ General Impression of Barcelona and Their Satisfaction with the City’s Cultural Sites

After the qualitative method through semistructured interviews with some of the respondents, the following observations were obtained: before visiting Barcelona, the majority of Chinese tourists think that the worldwide famous football team, FC Barcelona, could represent the city as its image. For general Chinese visitors, their organic image of Barcelona is almost nothing more than the football club, flamenco, and bullfighting, and many of them still do not know that bullfighting is prohibited in Barcelona. In short, they lack knowledge of the identity of the city. However, after the visitation, they change their perspective. It is observed that during the trip, Chinese visitors are conscious that Barcelona is a city of history and culture. According to the results, Chinese tourists appreciate the cultural and historical atmosphere of the destination, which also has a significant influence on their travelling moods.

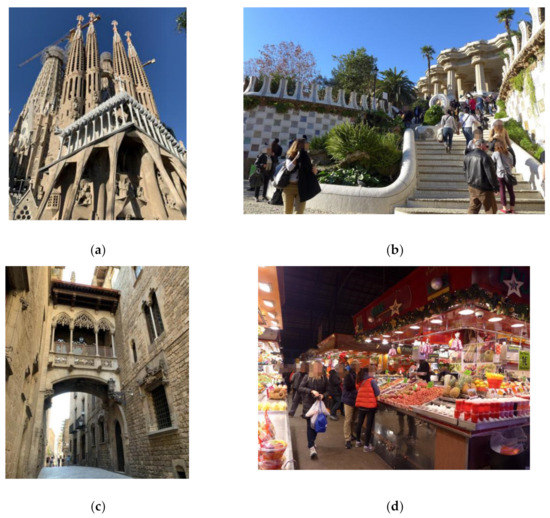

Regardless of where the Chinese visitors are from and their professions, the majority of them almost had the same order of satisfaction with cognitive attributes: cultural sites (Sagrada Familia, Park Güell, Barrio Gótico, and La Boquería, among others) (Figure 3), city atmosphere, social and natural environment, service and information, and tourism hot spots (from high to low mean number order). The results suggest that Chinese respondents enjoyed Barcelona’s cultural sites, which is logical, because compared to sunbathing and going to the beach, many Asian tourists prefer to visit cultural hot spots to learn more about the city’s culture and history. They are also satisfied with the city’s atmosphere, and for them the natural and social environment is neutral. According to the interviews, the tourist information and services still have room for improvement. Another interesting finding from the interviews is that Chinese tourists quite enjoyed the tourism experience products related to the local culture, including gastronomy. Some local cuisine workshops in Barrio Gótico or la Boquería were welcomed by the Chinese visitors. An expert chef teaches tourists how to prepare healthy Spanish foods, such as tapas (small Spanish savory dishes, served with drinks), traditional paella (a dish of rice and seafood, served in a large shallow pan) and sangría (a drink of red wine mixed with fruit), and afterwards, the visitors can make these foods by themselves. From the findings, we can see that, with the increase in the number of outbound trips by Chinese tourists, their tour gradually changed from the previous stepping-on-spots style with intensive schedules to a relatively more immersive tour experience.

Figure 3.

(a) Sagrada Familia. Source: own preparation. (b) Park Güell. Source: own preparation. (c) Barrio Gótico. Source: own preparation. (d) La Boquería. Source: own preparation.

4.3. Chinese Tourists’ Travel Motivations of Cultural Experiences and Networking—Barcelona’s TDI

As Table 5 shows, the majority of the Chinese tourists have a strong motivation regarding gaining a cultural experience when visiting Barcelona (M: 4.43) and followed by a “search for natural beauty”. The motivations of “relaxation” and “prestige and networking” have similar mean numbers.

Table 5.

Mean and SD of MOTs.

Multiple linear regressions were calculated to predict cognitive (COGs) and affective (AFF) evaluations and Barcelona’s overall image based on the travel motivations. As Table 6 shows, the travel motivation of gaining cultural experiences has a significant influence on the cognitive evaluation of the city atmosphere and cultural sites, meaning that if Chinese tourists visit Barcelona with the aim of gaining more cultural experiences, they will be very satisfied with the atmosphere in Barcelona. This is in contrast with the travel motivations of European visitors, many of whom visit a seaside destination because of its sun and sand and the pleasant and casual atmosphere, meaning that they can spend holiday time with their families and friends at the beach [65,88]. Meanwhile, the travel motivation of prestige and social networking has a significant influence on the cognitive evaluation of tourism hot spots, affective evaluation, and Barcelona’s overall image. The “prestige and networking” is a very interesting factor according to the interviews with the tourism-related experts. Among the segments of Chinese tourists in Barcelona, businesspersons are among the most important segments from the perspective of the quantity of the tourists and the economic reasons, such as the annual World Mobile Congress. “Chinese businesspersons are extremely sensitive to protecting and enhancing face” [52]. We can observe that “prestige and networking” have a special significance for Chinese tourists.

Table 6.

Effects of MOTs on COGs, AFF and OTDI.

As the study indicates, Chinese visitors have a strong motivation regarding gaining a cultural experience and are highly satisfied with the cultural sites; prestige, social networking, and cultural sites are the key factors that affect the formation of Barcelona’s image in the Chinese tourists’ eyes.

5. Discussion

According to the results, the motivation regarding prestige and networking significantly favors the affective aspect of Barcelona’s TDI. It is worth discussing the reasons for this.

5.1. Why Do Chinese People Greatly Value Prestige and Social Networking?

As mentioned in the literature review, in the Chinese pro-social cultural background, the interpersonal relationship is significantly important. Prestige and networking are key factors for Chinese people in collectivistic society. These two key factors are closely related to the concept of “face” and self-image. Face acts as an important norm that most Chinese people follow in their interactions with others [60]. It is a key concept for understanding the Chinese mindset and behavior. “Facework” is a behavior that helps Chinese people to build their individual reputation and maintain relationships with others. In order to gain face, building a good image is very useful. The concept of face can be understood through a person’s travels.

5.2. Individual’s Face-Building (Zuomianzi) during the Trip

When traveling, many Asian tourists attach great importance to commemoration through taking photos to prove that they have been there. To show that they have visited many places, the more countries the tour route passes through, the more popular the tour will be in China, especially for many first-time visitors. Moreover, the selected attractions must be famous or well-known. In short, the reputation of the tourist destinations is appropriated to gain and build a more impressive face. Therefore, the prestige of the destination is also one of the criteria for Chinese tourists to perceive a city image.

Face-building is also reflected in shopping. In order to gain face (huode mianzi), consumers are willing to spend more money for branded and novel products. When there is a distance between the real self and the ideal self, they want to make up for that by modifying their external image. Therefore, sometimes, Chinese consumers hope to make a breakthrough in the crowd through the use of well-known luxury goods, so that their personal status can be improved.

5.3. Face-Giving and Maintenance of Relationship

Face is mutual in nature [52]. As the “face” of social prestige, it can be “gained” or “lost”. It can also be “given” or “given away like a gift”. To offer a person a handsome present is to give him/her face. The image of a Chinese person is mainly defined by the people he/she knows. Therefore, Chinese people participate in a collectivistic culture; that is, apart from protecting their own sense of respect (self-face), they also pay great attention to maintaining the other individual’s (other-face) sense of dignity and respect in an interaction [89]. Groups maintain a status or reputation and individuals are concerned about not only their individual face but also the face of their groups [51]. Therefore, giving face is one way of maintaining harmonious relationships with others [90]. In order for one to function successfully in the Chinese society, gift-giving is essential.

Therefore, prestige and social networking are highly valued in a pro-social culture background. Gift purchasing is one of the most important parts of their daily life and their tourist activities. Chinese consumers perceive products from foreign countries, especially developed countries, as being of high quality, well designed, and associated with modernity and prestige [18]. Therefore, we can say that prestige and social networking significantly affect Chinese tourists’ perception of TDI because of the influence of their collectively oriented cultural background.

6. Conclusions

This study aimed to investigate TDI from a national cultural perspective and to explore the influences of culture on a visitor segment’s TDI. Barcelona and the Chinese market were used as the empirical portion of the study. As mentioned in the introduction and literature review, the knowledge on TDI needs to be expanded cross-culturally by studying further the perception of Chinese tourists regarding Western destinations. Therefore, continuing with Barcelona’s TDI measurement scale for Chinese tourists created in Tian and Cànoves’ (2020) research, this article conducted a study to test and develop the scale [18]. This paper began by analyzing the importance given to the perception of the tourists by the influence of the visitor segment’s CVO, and analyzing the Chinese collective culture, which greatly values the harmony between relationships and personhoods, as well as the importance of the concept of “face” in order to perform well in the collective society and maintain interpersonal relationships. Afterwards, this research went further to explore Chinese tourists’ TDI of Barcelona by investigating their cognitive and affective evaluations of the city’s image, their travel motivation and their satisfaction with the tourist landscapes.

The results show that Chinese tourists have a strong travel motivation regarding gaining a cultural experience, and that they appreciate the cultural sites of the destination, such as Sagrada Familia and Barrio Gótico, more than other cognitive attributes of the TDI. It is worth mentioning that there exists a significant influence of the travel motivation of prestige and social networking, respectively, on the cognitive attributes of the destination’s tourism landscapes, and on the visitors’ affective evaluation; there is significant influence of the same travel motivation on their evaluation of the overall image of the destination. Therefore, the travel behavior, such as social networking during the trip, the prestige of the destination or the tourist landscapes of the city, and visiting the cultural sites and landscape, thus enriching their cultural experience in relation to the destination, are the key attributes of the formation of TDI for the segmentation of Chinese tourists.

Furthermore, the research offers a detailed analysis of the reasoning motivating the travel behavior of gift-shopping and social networking. This paper also explains the influence of Chinese people’s pro-social cultural background and their tradition of collectively orientated thinking on their travel behavior, which influences their perception of the city’s image.

To conclude, it is crucial for the government or marketing organizations to know that what Chinese tourists expect from Barcelona is different from the expectations of European people. As mentioned in the literature review, Barcelona’s TDI has always been inseparable from the sun, the beach and football. This is more suitable for tourists from European and American countries. However, according to the results obtained, the main motivation for most Chinese tourists to Barcelona is to gain a deeper understanding of the local culture and history. During the tour, visiting historical and cultural sites and landscape is the first choice for them, and their satisfaction of this is quite high. From a historical point of view, as early as around the 14th century, Chinese silk craftsmanship was introduced to Spain via the ancient Silk Road. Since then, there have been close ties in many aspects between the two countries, such as trade and culture. After the accumulation of these connections between Spain and China throughout their long histories, the two parties have been following each other’s footsteps in the process of their cultural formation. Therefore, Chinese tourists are very willing to learn about and experience local culture in great depth by visiting cultural sites and landscapes and participating in cultural activities. On the other hand, shopping is not the main motivation for Chinese tourists to travel, but it is one of their main travel behaviors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.T., G.C., Y.C., J.F.-G. and J.M.P.F.; methodology, M.T.; software, M.T.; validation, M.T., G.C. and Y.C.; formal analysis, M.T.; investigation, M.T.; resources, G.C., Y.C., J.F.-G., J.M.P.F.; data curation, M.T.; writing—original draft preparation, M.T.; writing—review and editing, M.T.; visualization, G.C.; supervision, M.T.; project administration, M.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and the protocol was approved by the Autonomous University of Barcelona.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Lee, G.; Lee, C.K. Cross cultural comparison of the image of Guam perceived by Korean and Japanese leisure travelers, importance performance analysis. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 922–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastenholz, E. ‘Cultural proximity’ as a determinant of destination image. J. Vacat. Mark. 2010, 16, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, C.B.; Armario, E.M.; Ruiz, D.M. The influence of market heterogeneity on the relationship between a destination’s image and tourists’ future behaviour. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaker, J.L.; Benet-Martinez, V.; Garolera, J. Consumption symbols as carriers of culture: A study of Japanese and Spanish brand personality constructs. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 81, 492–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reisinger, Y.; Turner, L. Cultural differences between Asian tourist markets and Australian hosts. J. Travel Res. 2002, 40, 295–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, Y.; Tinkham, S.F. Brand personality structures in the United States and Korea: Common and culture-specific factors. J. Consum. Psychol. 2005, 15, 334–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Stepchenkova, S. Understanding destination personality through visitors’ experience: A cross-cultural perspective. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2017, 6, 416–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H. A cross-cultural comparison of memorable tourism experiences of American and Taiwanese college students. Anatolia Int. J. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2013, 39, 514–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Chick, G.E.; Zinn, H.C.; Absher, J.D.; Graefe, A.R. Ethnicity as a variable in leisure research. J. Leis. Res. 2007, 39, 514–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.M.; Lu, L. A review of studies on cross-cultural tourist attitude and behavior. Tour. Trib. 2008, 23, 82–87. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, J.D. Image: A Factor in Tourism. Ph.D. Thesis, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Gartner, W.C. Image formation process. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 1993, 2, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloglu, S.; McCleary, K.W. A model of destination image formation. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 868–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallarza, M.G.; Saura, I.G.; García, H.C. Destination image: Towards a conceptual framework. Ann. Tour. Res. 2002, 29, 59–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D.; Chi, C.G. The Routledge Handbook of Destination Marketing; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gunn, C.A. Vacationscape: Designing Tourist Regions; University of Texas: Austin, TX, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Beerli, A.; Martin, J.D. Factors Influencing Destination Image. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 657–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M.; Cànoves, G. Exploring emotional and memorable tourism experience. In Tourism Product Development in China, Asian and European Countries; Luo, Y.H., Jiang, J.B., Bi, D.D., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 137–151. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, S.D.F. Destination image: Origins, Developments and Implications. PASOS Rev. Tur. Patrim. Cult. 2011, 9, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, P.Q. Integrated Design of Street Facilities and Promotion of Urban Tourism Image; China Social Science Press: Beijing, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- TravelMole. Logo Motive: How Spain Got Its Miro. 2009. Available online: https://www.travelmole.com/news_feature.php?id=1140099 (accessed on 9 May 2021).

- Cheng, J.L. Study of Tourism Destination Image Perception: An Example of Zhengzhou, Kaifeng & Luoyang, China. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Henan, Kaifeng, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Tapachai, N.; Waryszak, R. An Examination of the Role of Beneficial Image in Tourist Destination Selection. J. Travel Res. 2000, 39, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, A.; Gómez, M.; Martín-Consuegra, D. Marketing information and destination image management. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2010, 4, 722–728. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.F.; Tsai, D.C. How destination image and evaluative factors affect behavioral intentions? Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 1115–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylos, N.; Andronikidis, A. Exploring the cognitive image of a tourism destination. Tourismos 2013, 8, 77–97. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, S.H.; del Bosque, I.A.R. Exploring the cognitive-affective nature of destination image and the role of psychological factors in its formation. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veasna, S.; Wu, W.Y.; Huang, C.H. The impact of destination source credibility on destination satisfaction: The mediating effects of destination attachment and destination image. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 511–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.J.; Ryan, C. Perceiving tourist destination landscapes through Chinese eyes: The case of South Island, New Zealand. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 582–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanjul, E.; Rvetta, P. “An Assessment of Plan China” Translated from Spanish Title. Observatorio Virtual Asia Pacífico. 2005. Available online: https://silo.tips/download/una-valoracion-del-plan-china (accessed on 25 April 2021).

- Otero, J.R. La Imagen de España y lo español hoy en China: Una Aproximación a la Diplomacia Pública. Huarta San Juan Geogr. Hist. 2008, 15, 113–119. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J.; Guia Julve, J.; Xu, H.; Cui, Q. Food habits and tourist food consumption: An exploratory study on dining behaviours of Chinese outbound tourists in Spain. J. Policy Res. Tour. Leis. Events 2020, 12, 82–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lojo, A. Chinese tourism in Spain: An analysis of the tourism product, attractions and itineraries offered by Chinese travel agencies. Cuad. Tur. 2016, 37, 243–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lojo, A. Young Chinese in Europe: Travel behavior and new trends based on evidence from Spain. Tour. Int. Interdiscip. J. 2020, 68, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lojo, A. Understanding a New Tourism Market and Destination Development: The Case of Chinese Tourism in Spain. Ph.D. Thesis, Autonomous University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso-Almeida, M.M.; Borrajo-Millán, F.; Yi, L. Are social media data pushing overtourism? The case of Barcelona and Chinese tourists. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemma, J.G.; Marta, S.P. Chinese Tourism and Its Effects on the Hospitality Industry in Barcelona. Master’s Thesis, HTSI School of Tourism and Hospitality Management, Ramon Llull University, Barcelona, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lojo, A.; Cànoves, G. New tourism trends in Barcelona. Chinese tourist experiences and local perceptions. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Tourism between Spain and China ICTCHS2015, Tianjin, China, 3–6 September 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lojo, A.; Cànoves, G. Chinese tourism in Barcelona. Key elements of a recent phenomenon. Doc. d’Analisi Geogr. 2015, 61, 581–599. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, M. Barcelona’s City Image as a Tourist Destination in the Chinese Market. Ph.D. Thesis, Autonomous University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, S.; Crompton, J. Cultural Variations in Perceptions of Vacation Attributes. Tour. Manag. 1988, 9, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKay, D.J.; Fesenmaier, D.R. An exploration of cross-cultural destination image assessment. J. Travel Res. 2000, 38, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvin, S.W.; Crotts, J.C.; Hefner, F.L. Cross-cultural tourist behaviour: A replication and extension involving Hofstede’s uncertainty avoidance dimension. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2004, 6, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluckhohn, C. Values and Value-Orientations in the Theory of Action: An Exploration in Definition and Classification. In Toward a General Theory of Action; Parsons, T., Shils, E., Eds.; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1951; pp. 388–433. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G.; Hofstede, G.J. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2005; p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.H.; Sun, H.R. Social Value Orientation and Fostering he Cooperation of Adolescents. J. Tianjin Normal Univ. 2001, 157, 77–80. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, G.S. Chinese Psychology and Behavior: A Study of Localization; China Renmin Unversity Press: Beijing, China, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, H.C.; Holt, R.G. A Chinese perspective on face as inter-relational concern. In SUNY Series in Human Communication Processes. The Challenge of Facework: Cross-Cultural and Interpersonal Issues; Ting-Toomey, S., Ed.; State University of New York Press: Albany, NY, USA, 1994; pp. 95–132. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, C.R. A Theory of Therapy, Personality and Interpersonal Relationships, as Developed in the Client-Centered Framework; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.L. Scale for Face and the Study of Relationship between Face and Self Consistency and Congruence. Master’s Thesis, Central China Normal University, Wuhan, China, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, W. The Remaking of the Chinese Character and Identity in the 21st Century: The Chinese Face Practices; Ablex Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Cardon, P.W.; Scott, J.C. Chinese Business Face: Communication Behaviors and Teaching Approaches. Bus. Commun. Q. 2003, 66, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, D.Y. On the concept of face. Am. J. Sociol. 1976, 81, 867–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.H. Chinese Characteristics, 3rd ed.; Graham Brash: Singapore, 1986; p. 16. [Google Scholar]

- Hui, V.; Bond, M. Target’s face loss, motivations and forgiveness following relational transgression: Comparing Chinese and US cultures. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2009, 26, 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwek, A.; Lee, Y.S. How “face” matters: Chinese corporate tourists in Australia. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2015, 32, 120–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.H. Communication and Face Games: An interactional Sociolinguistic Approach; Shanghai Foreign Language Education Press: Shanghai, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, P.; Levinson, S. Politeness: Some Universals in Language Usage; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Earley, P.C. Face, Hormony, and Social Structure: An Analysis of Organizational Behavior Cross Cultures; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, H.L.; Huang, S.S.; Brown, G. The influence of face on Chinese tourists’ gift purchase behaviour: The moderating role of the gift giver-receiver relationship. Tour. Manag. 2017, 62, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, K.K. Face and Favor: The Chinese Power Game. Am. J. Sociol. 1987, 92, 944–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.M.; Fan, L.J.; Ye, M.F. An empirical study on Chinese face and its effect on Consumer’s attitude toward advertising of luxury. Nankai Bus. Rev. 2012, 15, 151–160. [Google Scholar]

- Observatori del Turisme a Barcelona. Tourism Activity Report. 2020. Available online: https://ajuntament.barcelona.cat/turisme/sites/default/files/2020_capsula1iaotb_1_1.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2021).

- Duran, P. The Impact of the Games on Tourism: Barcelona: The Legacy of the Games, 1992–2002. Available online: https://www.sportsdestinations.com/management/economics/impact-olympic-games-tourism-8492 (accessed on 11 May 2021).

- Palou, R.S. Destinació BCN. Història del Turime a la Ciutat de Barcelona; Editorial Efadós: Barcelona, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ajuntament Barcelona. Anuari Estadístic de la Ciutat de Barcelona 2020. 2020. Available online: https://www.bcn.cat/estadistica/castella/dades/anuari/Anuari2020_AAFF.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2021).

- Milano, C. Overtourism and Tourismphobia: Global Trends and Local Contexts; Ostelea School of Tourism and Hospitality: Barcelona, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, G. European Cultural Tourism: A View from Barcelona. Inaugural Conference for the Austrian National Cultural Tourism Policy, Vienna, Austria. 2004. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/2393237/European_Cultural_Tourism_A_view_from_Barcelona (accessed on 13 May 2021).

- Generalitat de Catalunya. 2018–2022 Strategic Tourism Plan for Catalonia. Available online: http://empresa.gencat.cat/web/.content/20_-_turisme/coneixement_i_planificacio/documents/arxius/Pla-estrategic-de-turisme-de-Catalunya-2018-2022_en.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2021).

- Ministry of Business and Knowledge. 2020 Tourism Strategy. Available online: http://empresa.gencat.cat/en/treb_ambits_actuacio/turisme/coneixement_planificacio/emo_planificacio/emo_planificacio_estrategica/ (accessed on 13 May 2021).

- Ajuntament de Barcelona. Strategic Tourism Plan 2020: Executive Summary. 2017. Available online: http://historicalcity.eu/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Barcelona.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2021).

- Zhu, H.; Liu, J.; Wei, Z.; Li, W.; Wang, L. Residents’ Attitudes towards Sustainable Tourism Development in a Historical-Cultural Village: Influence of Perceived Impacts, Sense of Place and Tourism Development Potential. Sustainability 2017, 9, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, G. Cultural tourism: A review of recent research and trends. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2018, 36, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapera, I. Sustainable tourism development efforts by local governments in Poland. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 40, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turisme de Barcelona. Turisme de Barcelona Aprueba las Líneas Estratégicas Para el 2021–2022. Available online: https://professional.barcelonaturisme.com/storage/medias/files/B07digUcSZ2MsO3Cgjvh4EiL7PuZNhxP7wmrsDf3.pdf (accessed on 14 May 2021).

- News of the State Council, the People’s Republic of China. The Number of Domestic Tourists in China Exceeded 6 Billion in 2019. 2020. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2020-03/10/content_5489697.htm (accessed on 18 April 2021).

- Ministerio de Industria, Comercio y Turismo. Plan Turismo Chino. 2011. Available online: https://www.mincotur.gob.es/es-es/gabineteprensa/notasprensa/documents/planturismochina.pdf (accessed on 21 April 2021).

- China Tourism Academy. Annual Report of China Outbound Tourism Develoment, 2020; China Tourism Academy: Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- China News. Joining the Battle for Chinese Tourists How Spain Started the “Turnover” Translated from Chinese Title. 2019. Available online: https://www.chinanews.com/hr/2019/08-19/8931080.shtml (accessed on 19 April 2021).

- Schengen Visa Info News. Schengen Visa Application Requirements. 2015. Available online: https://www.schengenvisainfo.com/schengen-visa-application-requirements/ (accessed on 19 April 2021).

- Schengen Visa Info News. Schengen Visa Rules Set to Change as of February 2020–Here’s What You Need to Know. 2020. Available online: https://www.schengenvisainfo.com/news/schengen-visa-rules-set-to-change-as-of-february-2020-heres-what-you-need-to-know/ (accessed on 19 April 2021).

- Holmes, D. Romance and Readership in Twentieth-Century France: Love Stories; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- De Nisco, A.; Napolitano, M.R.; Mason, M.C.; Viglia, G. Country Image as Segmentation Tool in the Emerging Markets: Evidence from Italy. In Proceedings of the Global Marketing Conference, Tokyo, Japan, 26–29 July 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis, V.; Prais, S.J. The Quality of Manufactured Products in Britain and Germany. Int. Rev. Appl. Econ. 1997, 11, 421–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovics, P. SPSS Tutorial & Exercise Book for Business Statistics; University of Miskolc: Miskolc, Hungary, 2012; Available online: http://gtk.uni-miskolc.hu/files/11206/SPSS+Tutorial+and+excersise+book.pdf (accessed on 26 April 2021).

- Smith, W.G. Does Gender Influence Online Survey Participation?: A Record-linkage Analysis of University Faculty Online Survey Response Behavior. ERIC Document Reproduction Service. 2008. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED501717.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Russell, J.A.; Pratt, G. A description of the affective quality attributed to environments. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1980, 38, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, S.; Kiumarsi, S. Tourist’s motivation and behavioral intention between sun and sand destinations. Int. J. Leis. Tour. Mark. 2017, 5, 319–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, V. Facework and Culture (Summary of a Forthcoming Article). Communication. 2018. Available online: http://oxfordre.com/communication/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.001.0001/acrefore-9780190228613-e-165 (accessed on 20 February 2018).

- Seligman, S.D. Dealing with the Chinese: A Practical Guide to Business Etiquette in the People’s Republic Today; Warner Communications: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).