Effects of Forestry Intensification and Conservation on Green Infrastructures: A Spatio-Temporal Evaluation in Sweden

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

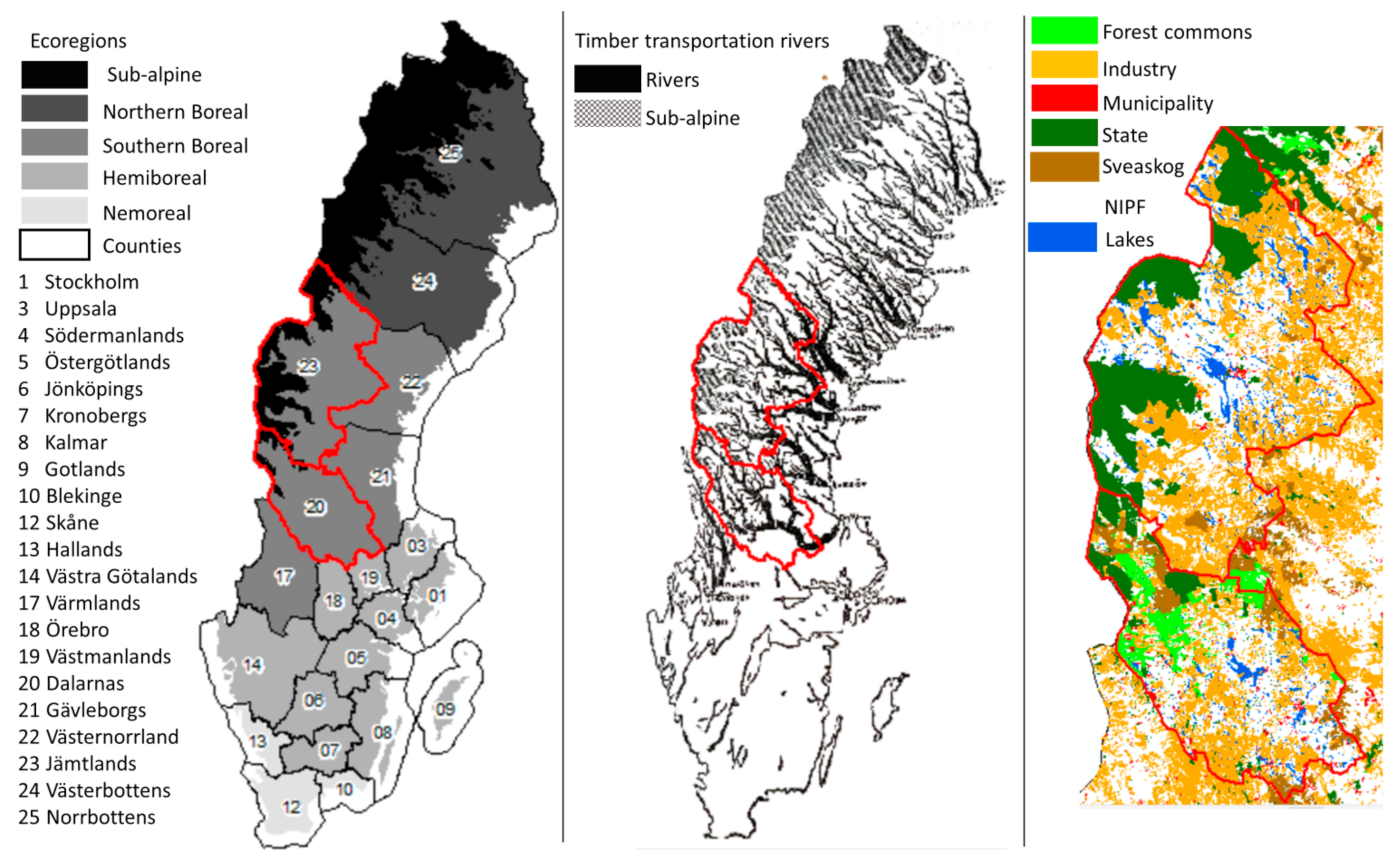

2.1. Study Areas

2.1.1. Boreal Forest History Gradients

2.1.2. Dalarna and Jämtland Counties

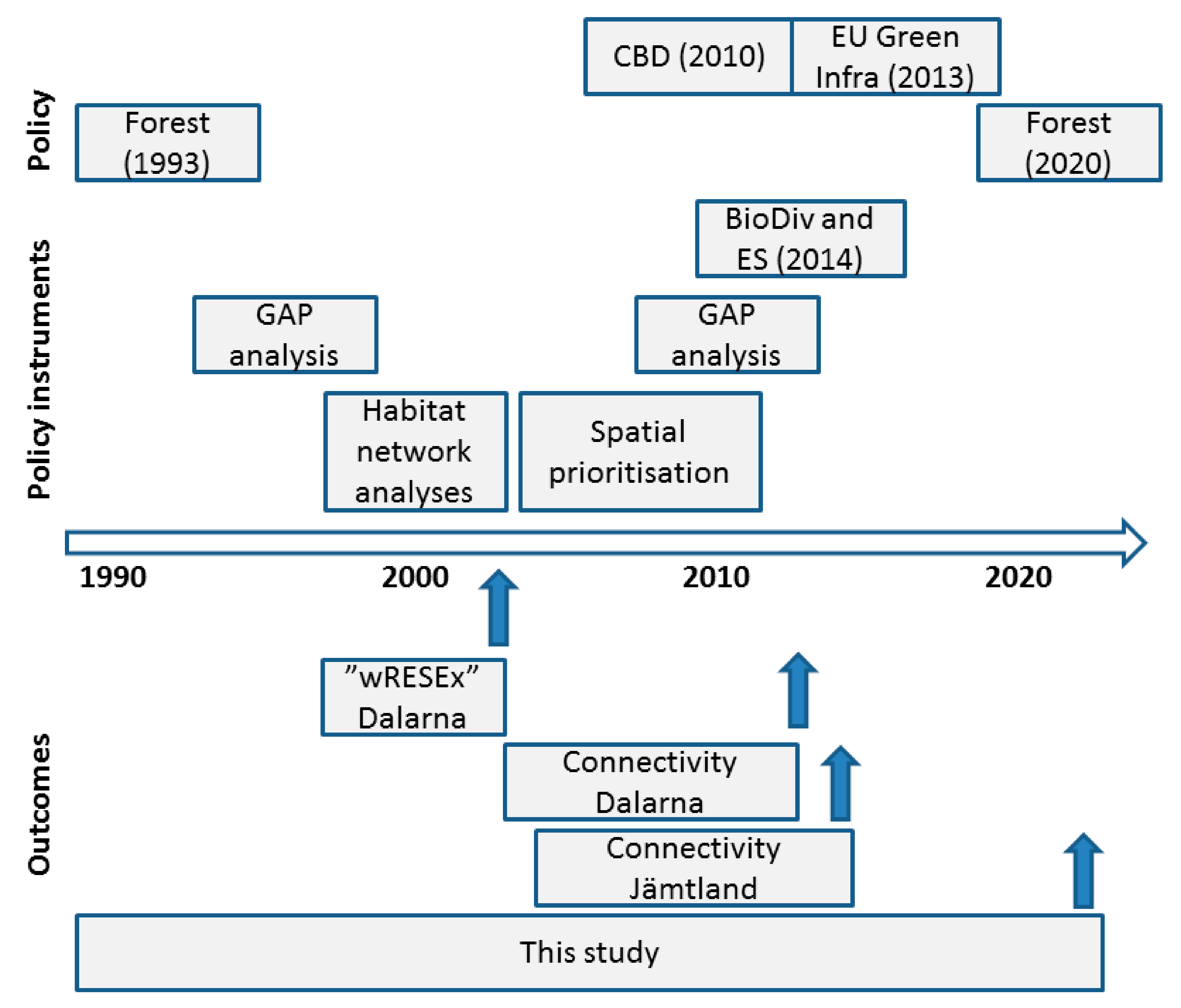

2.1.3. Previous Assessments of Habitat Networks in Dalarna and Jämtland Counties

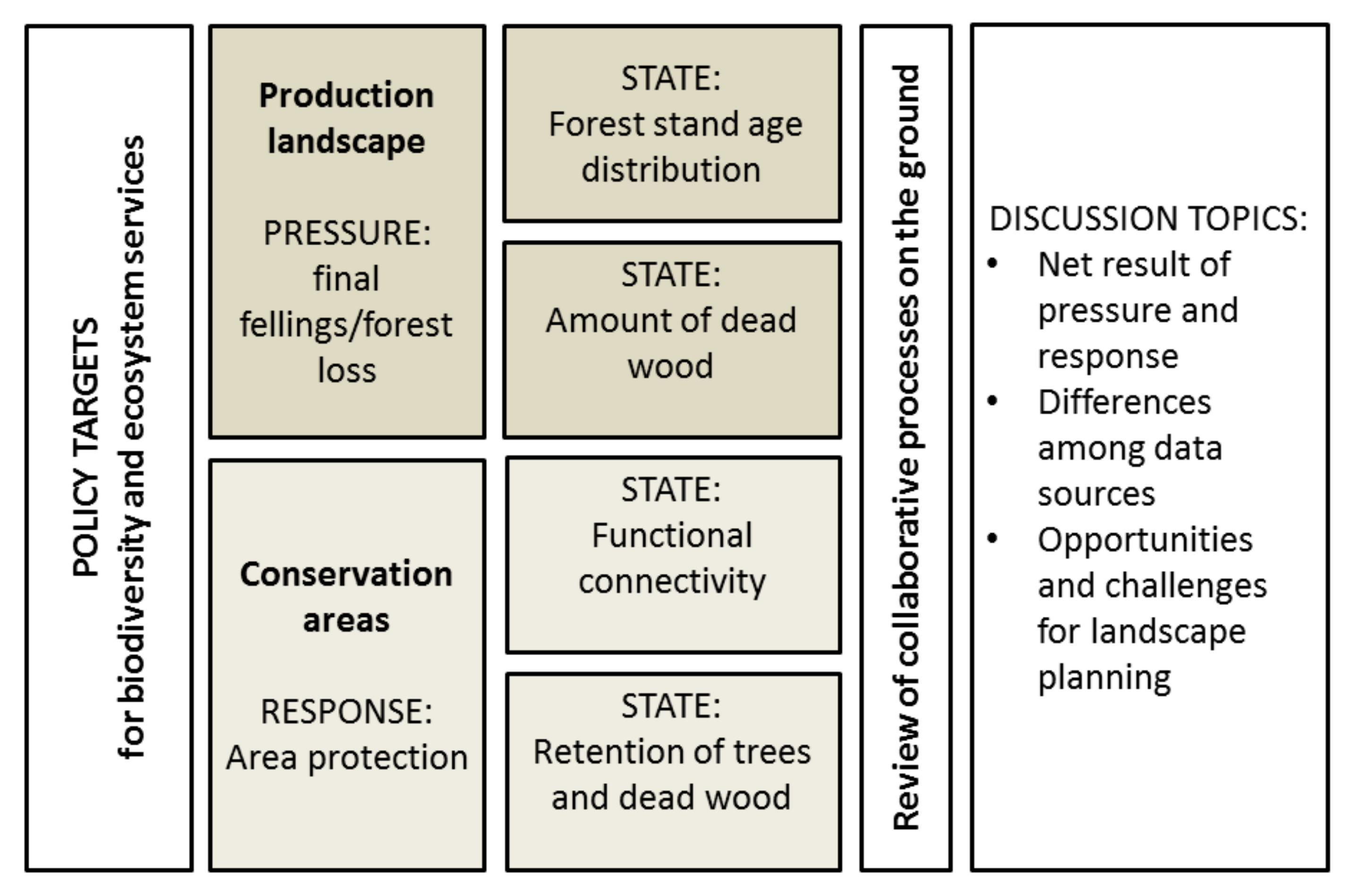

2.2. Overview of Methods to Assess Policy Implementation Outcomes

2.3. Production Landscapes as Matrix

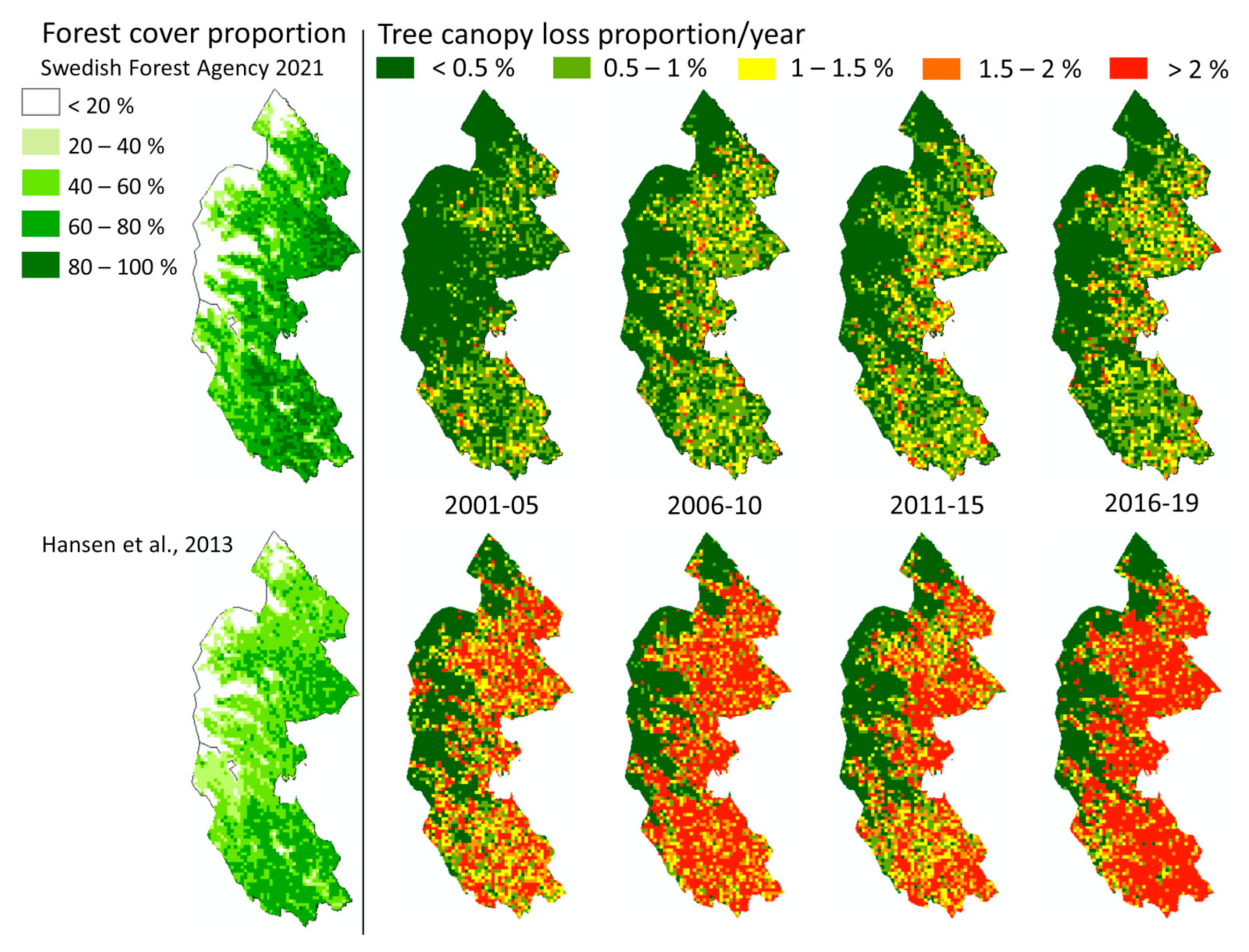

2.3.1. Forest Canopy Loss

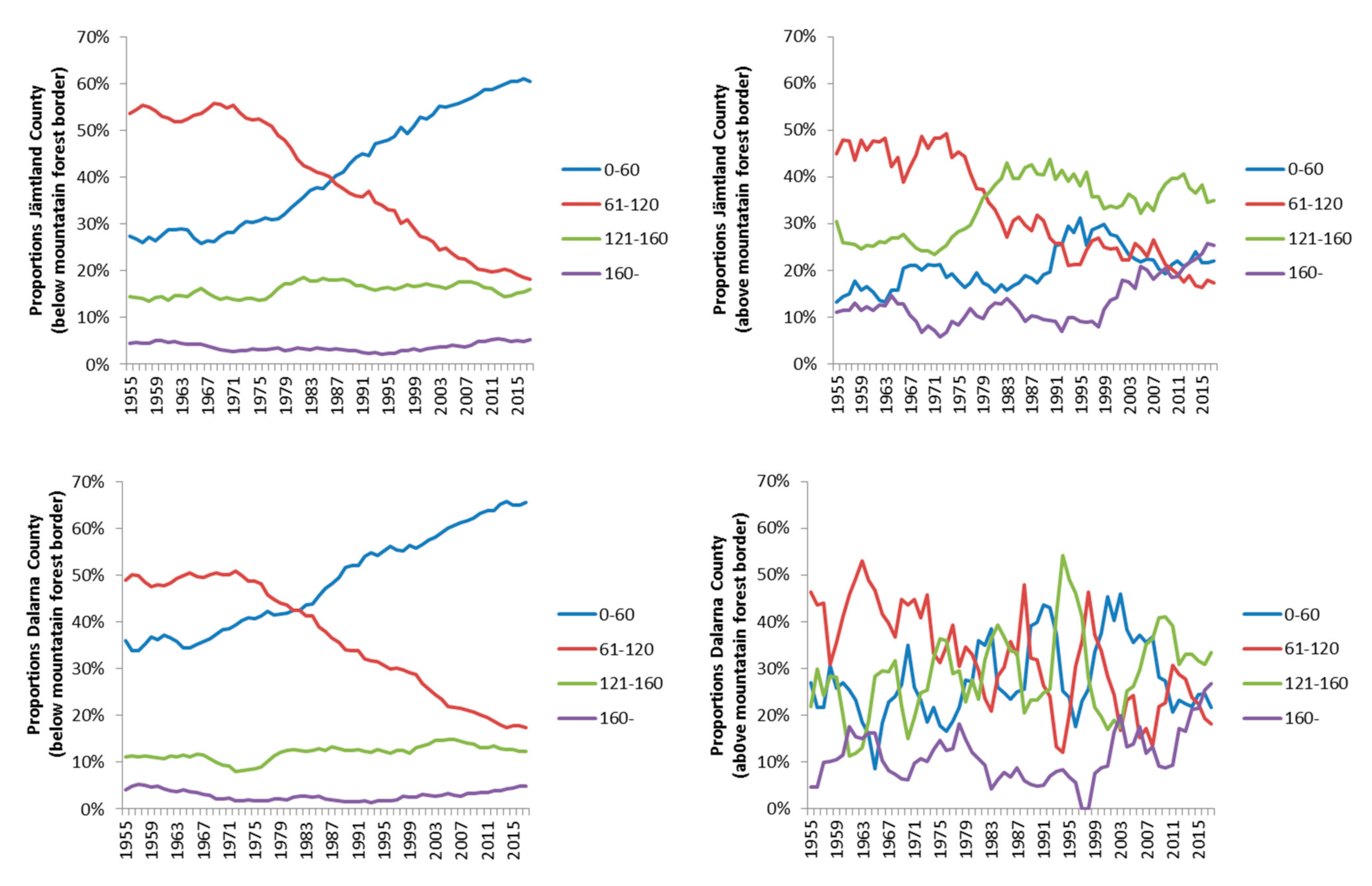

2.3.2. Age Distributions

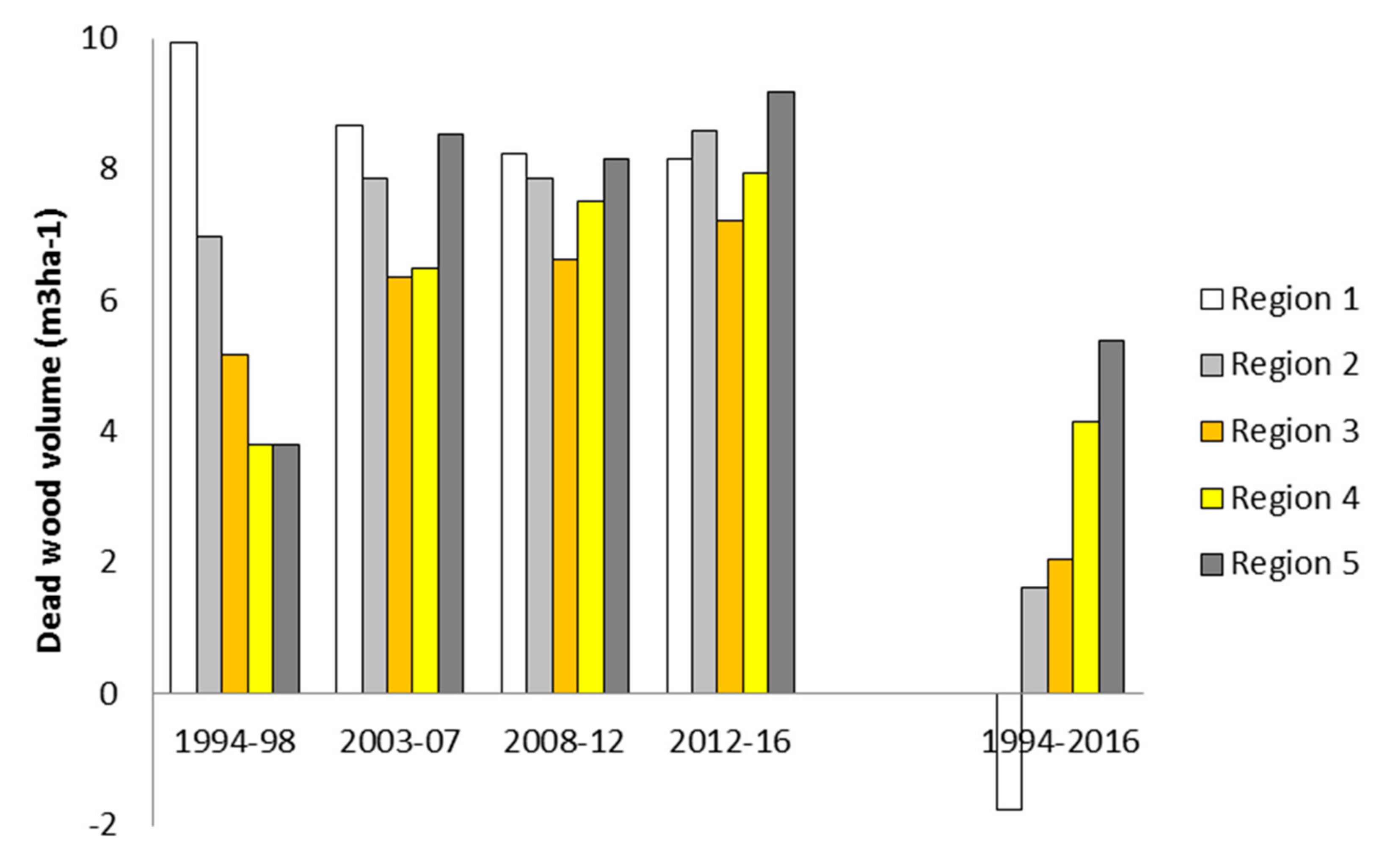

2.3.3. Dead Wood

2.4. Conservation Areas

2.4.1. Protected Areas

2.4.2. Habitat Modelling to Assess Functional Connectivity

2.4.3. Retention of Trees and Dead Wood

2.5. Narratives of What Happens on the Ground

3. Results

3.1. The Production Landscape as the Matrix

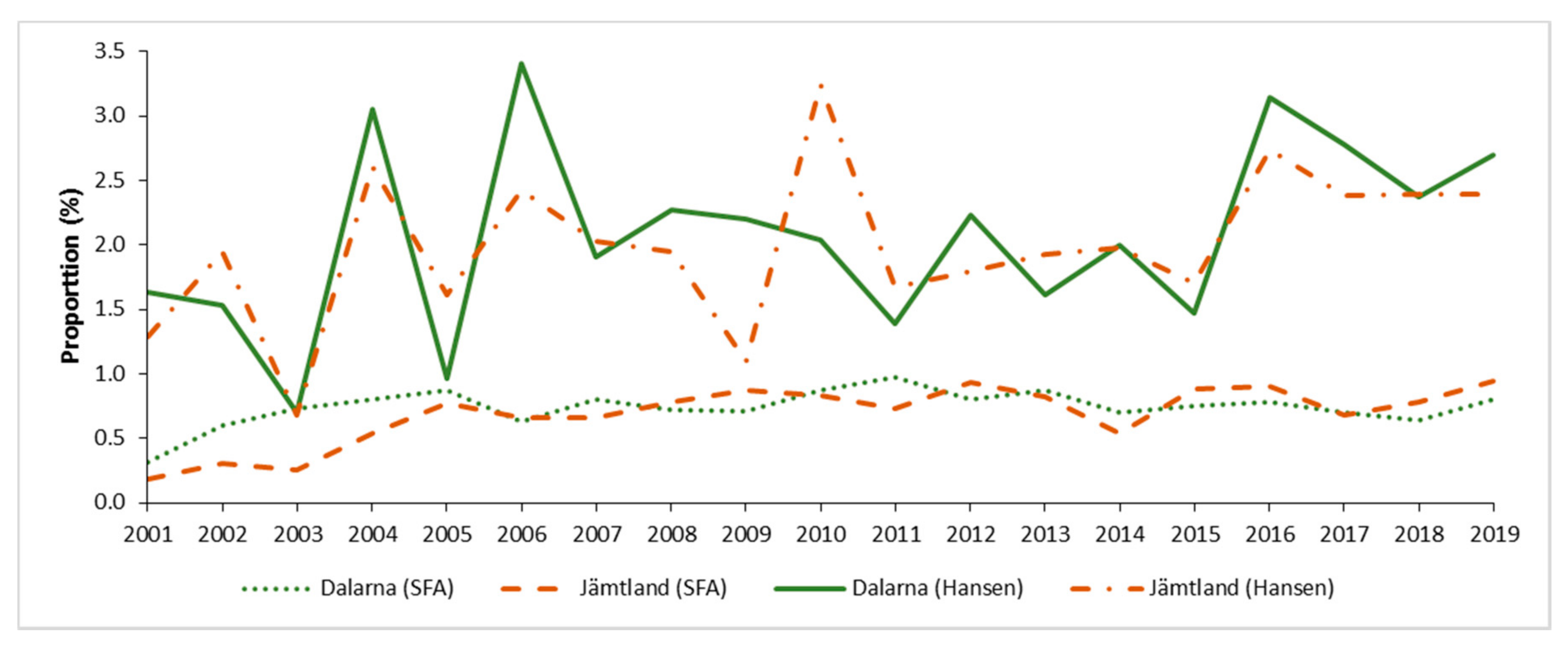

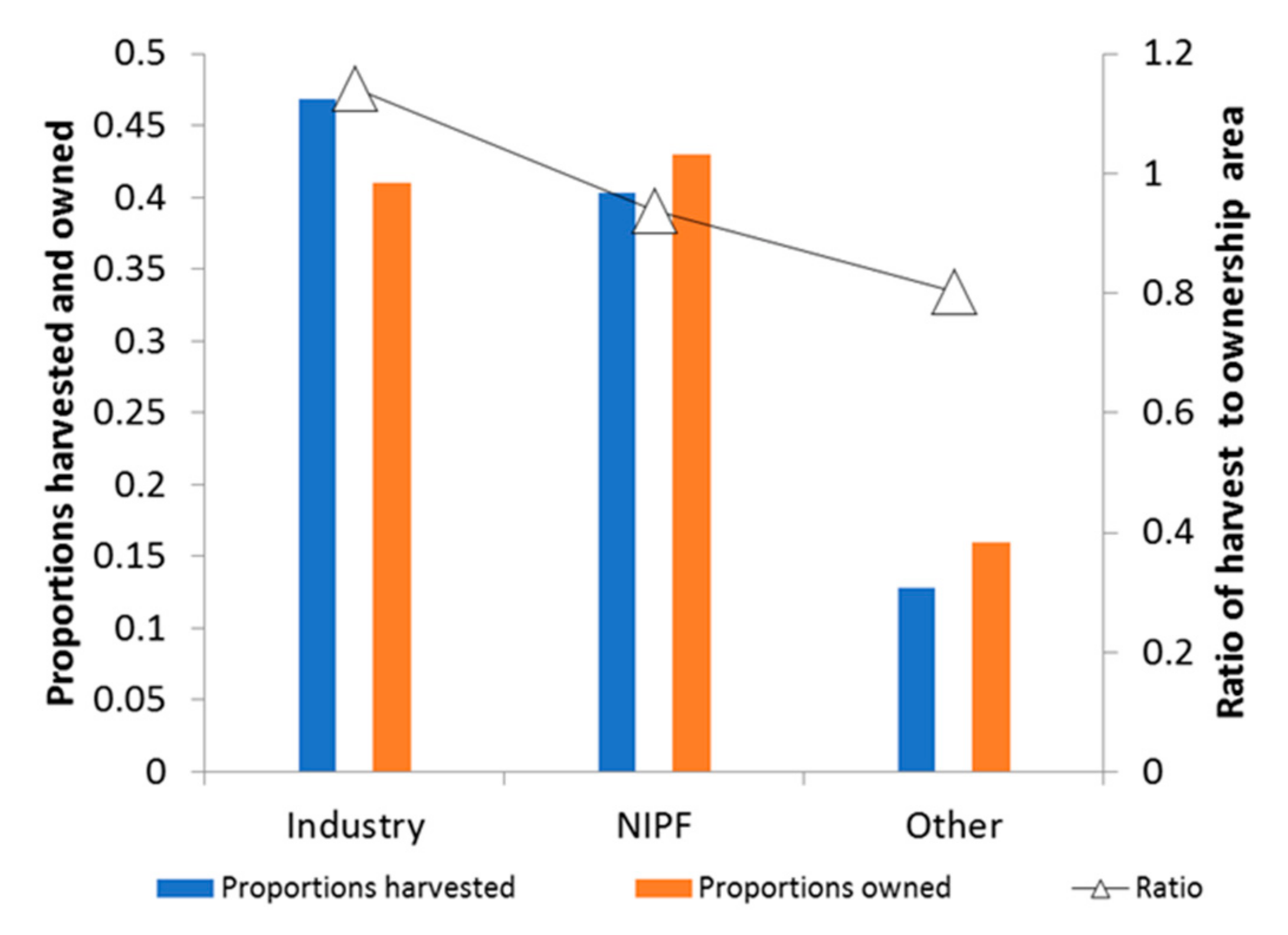

3.1.1. Tree Canopy Loss and Final Fellings

3.1.2. Landscape Scale—Forest Stand Age Distributions

3.1.3. Stand Scale—Dead Wood

3.2. Conservation Areas

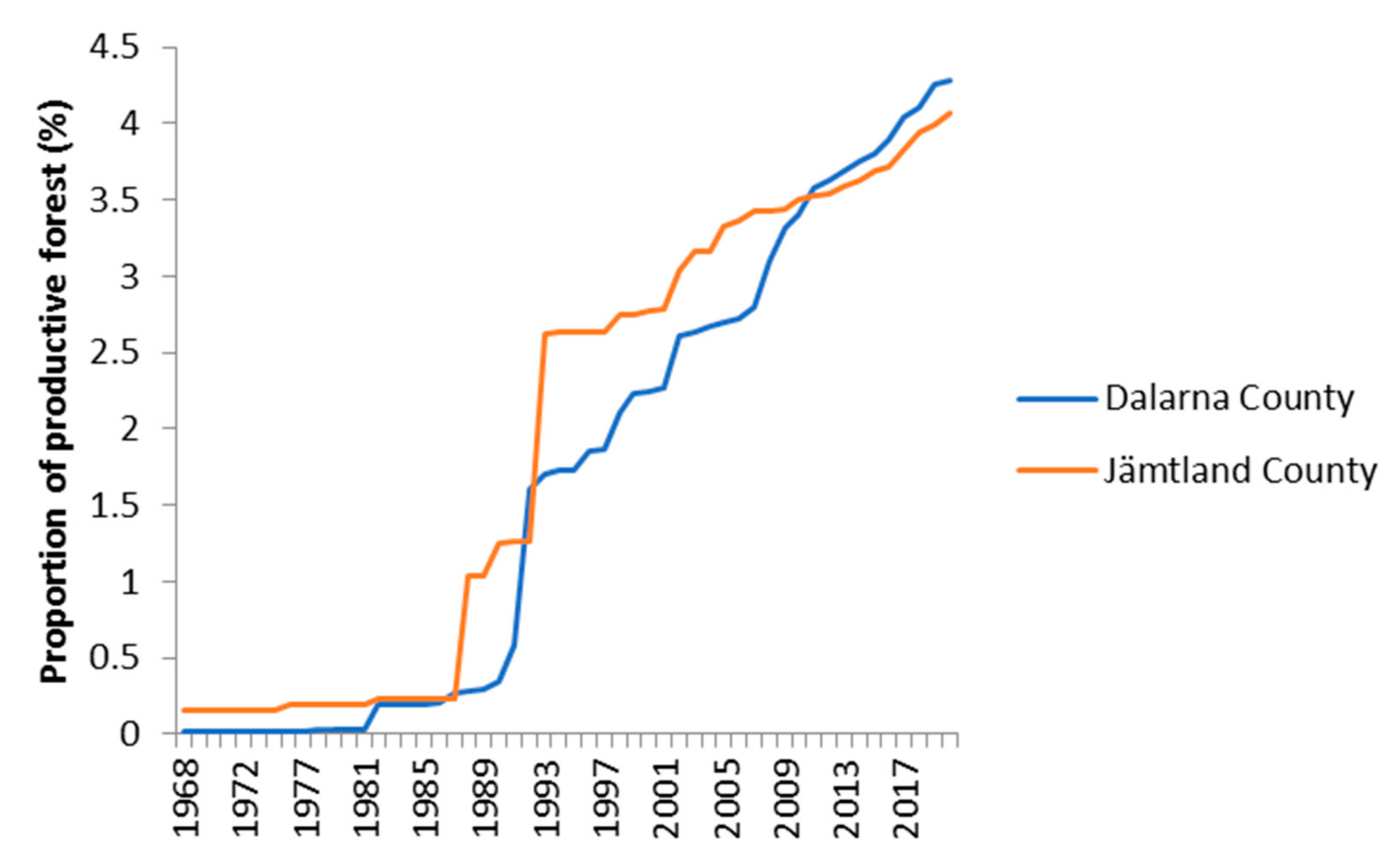

3.2.1. Establishment of Formally Protected Areas

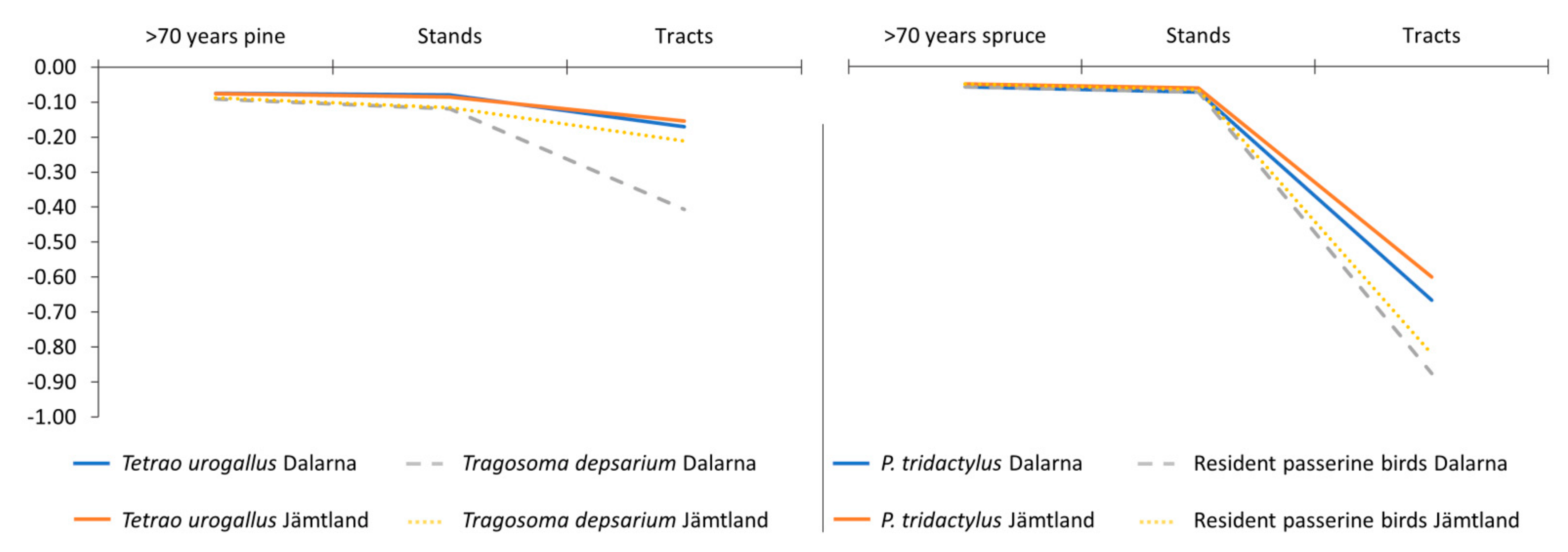

3.2.2. Green Infrastructure Connectivity in Dalarna (2002–2012) and Jämtland (2000–2013)

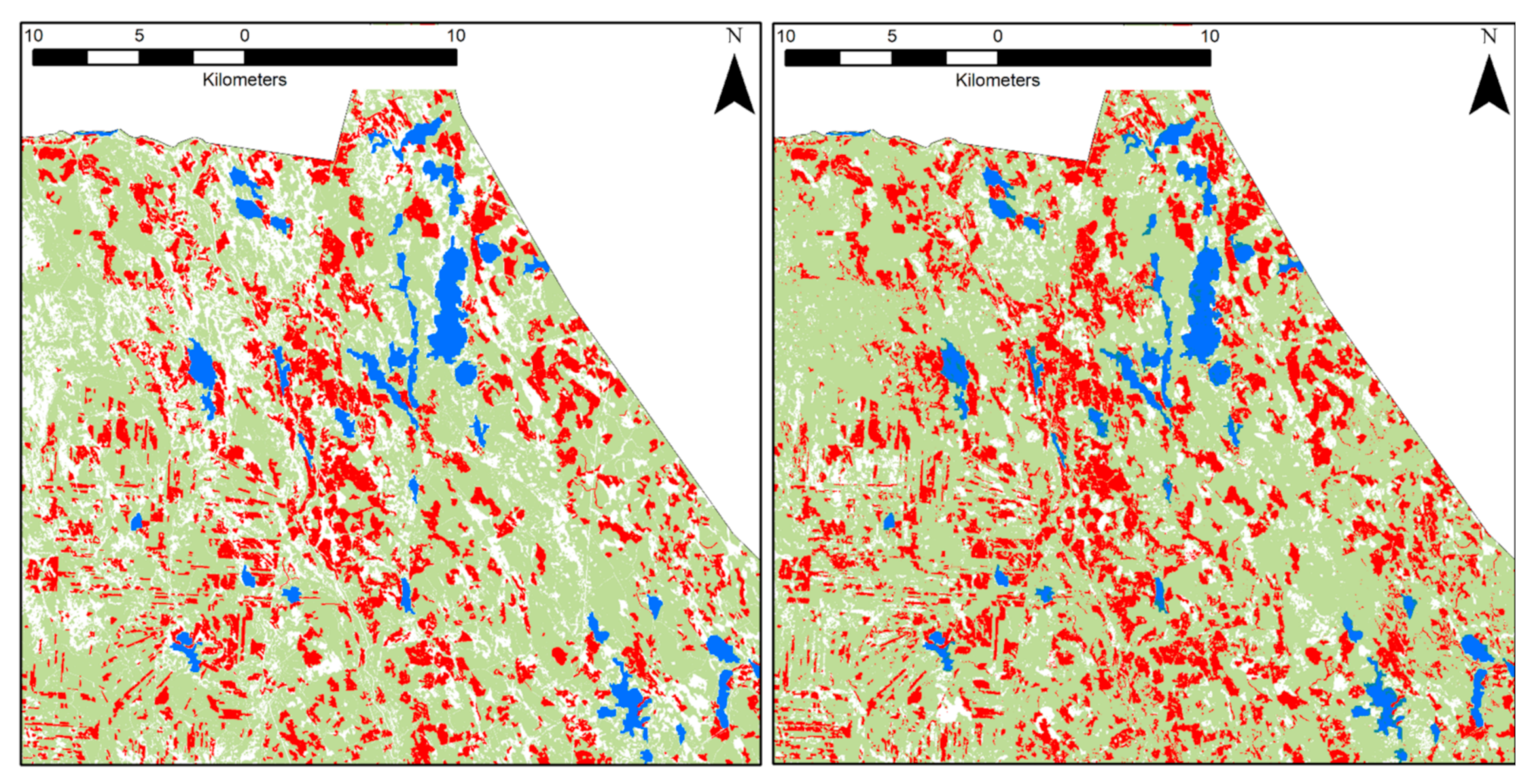

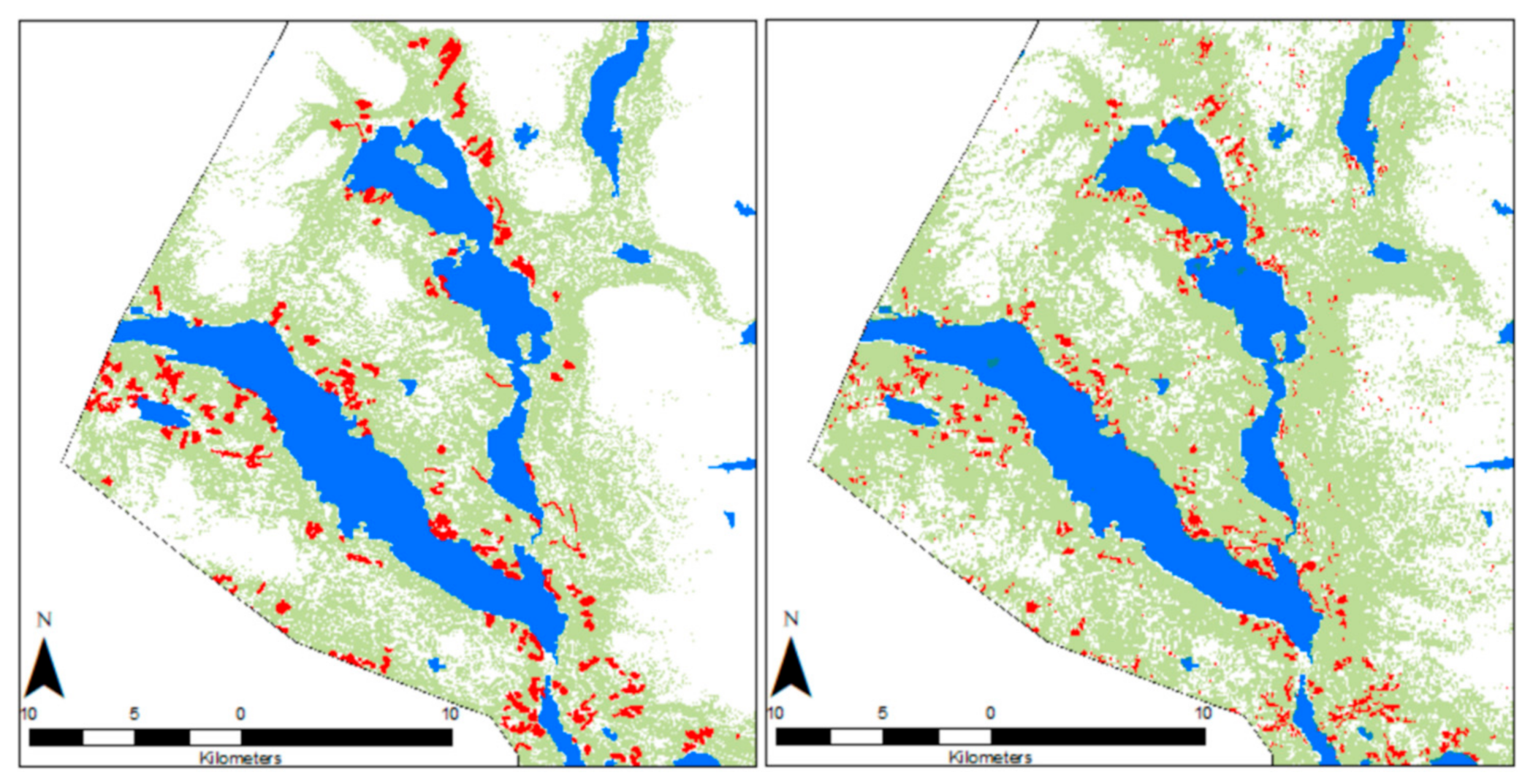

3.2.3. Connectivity of Green Infrastructures in Dalarna and Jämtland (2001–2019)

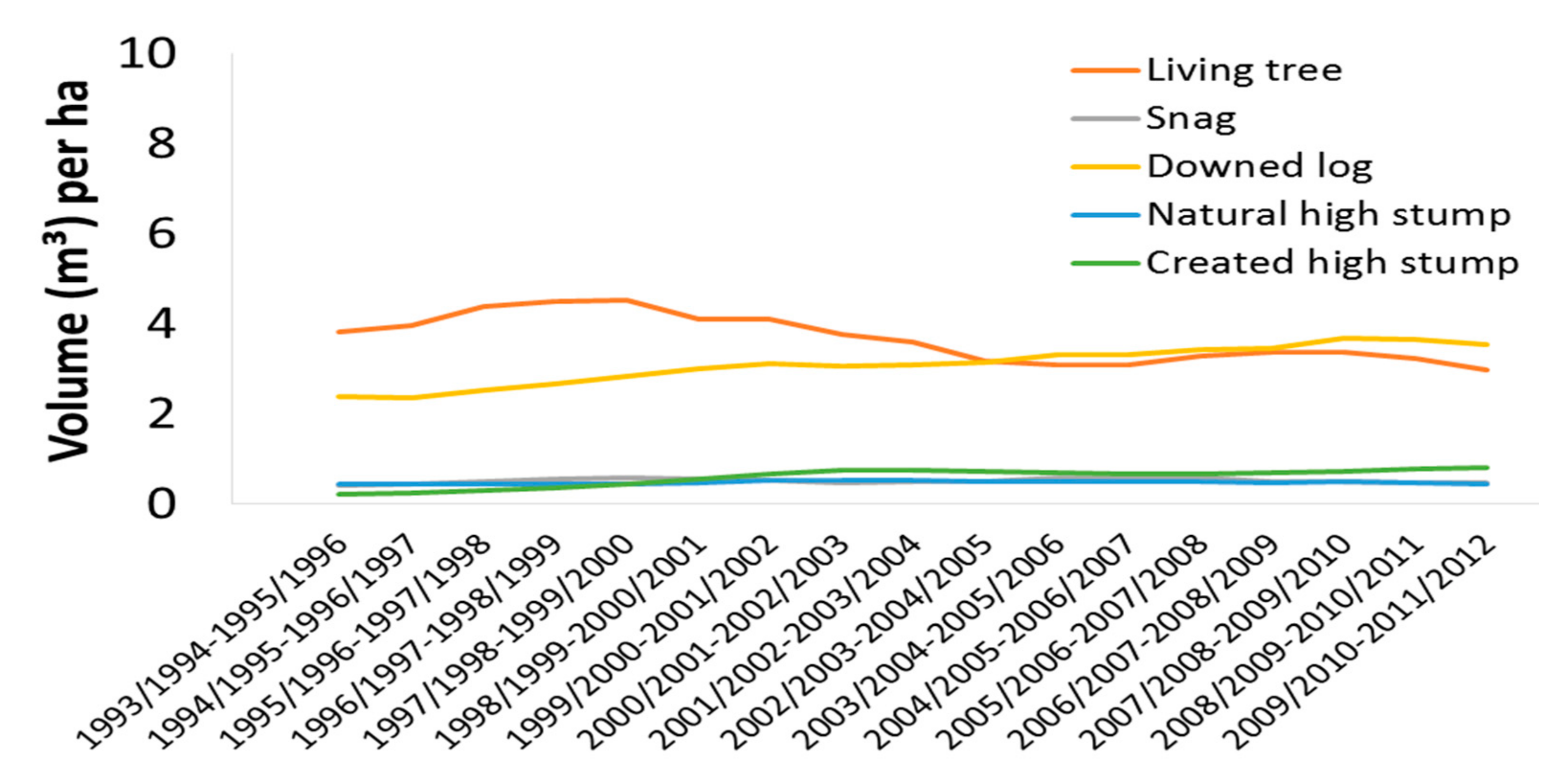

3.2.4. Stand Scale Retention of Dead Wood in Different Stages of Decay, and Trees

3.3. Narratives

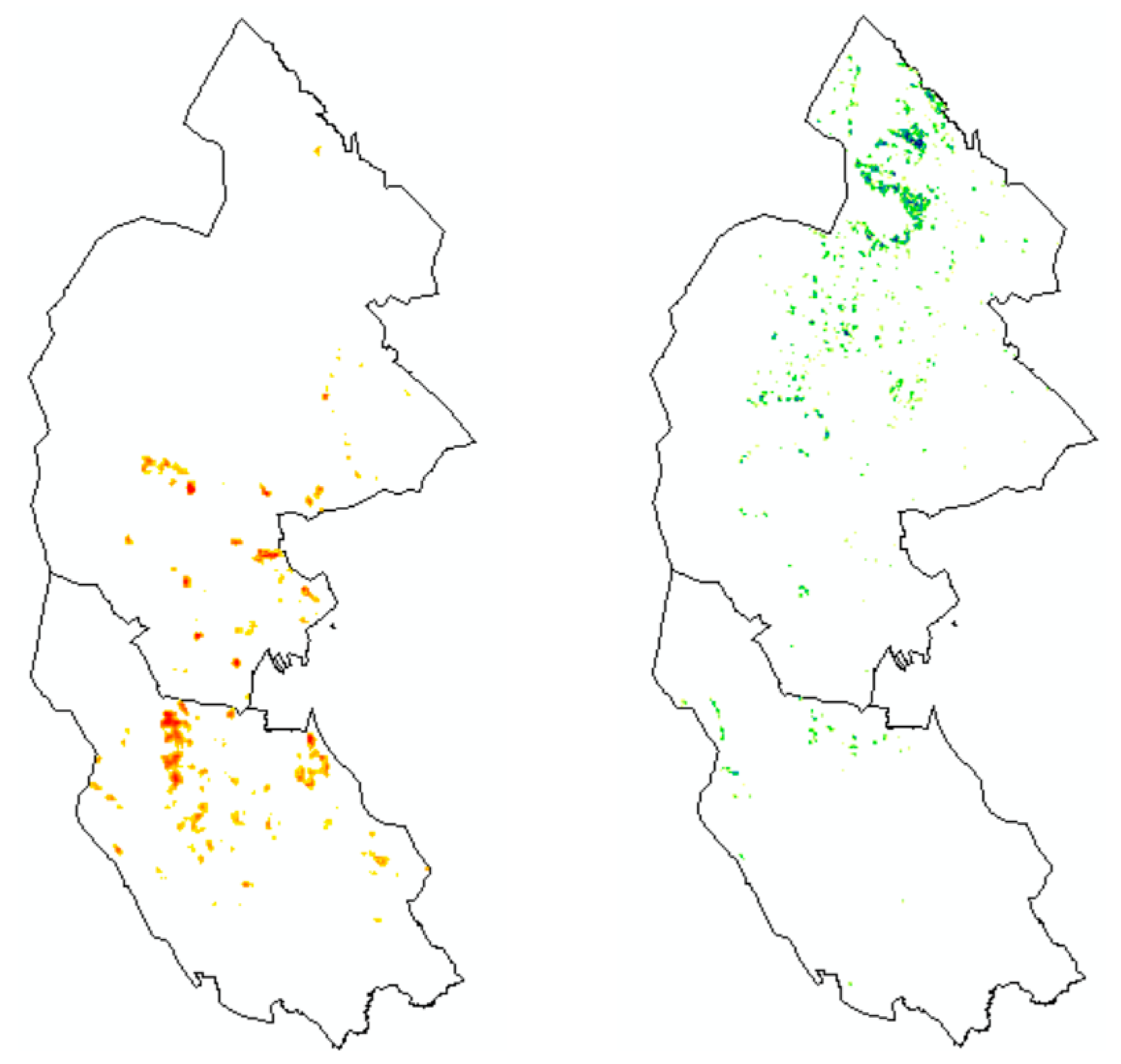

3.3.1. Core Region of Gåsberget

3.3.2. Core Region of Björkvattnet

4. Discussion

4.1. The Net Result of Pressure and Response

4.2. Data Sources to Be Used with Care

4.3. Landscape Planning Based on Informed Dialogue, or Truth Decay

- Form networks of actors and stakeholders. Initially, self-organization of fora for conservation and use, gradually based on mapping of stakeholders and actor analysis in the focal area, is needed. There are several selection principles. In addition to the area principle for stakeholder analysis, since perceived problems often cover a limited area, the principle of interest should be considered. Green infrastructure policy aims at both biodiversity conservation, and also support human well-being and welfare. Increased urbanisation, public concerns about human footprints caused by excessive flying to a remote tourism destination, and recently the increased use of protected areas and green spaces increases the number and diversity of green infrastructure beneficiaries. For example, in the US, people increased the use of green infrastructure to cope with the stress of the COVID-19 pandemic and to perform outdoor activities with social distancing [103]. The same pattern is observed in Sweden. It is difficult to run processes that do not consist of committed people with financial resources. The principles of relevance and representation are used to ensure that the composition of the groups does not become unequally distributed. The narratives about green infrastructure core regions/areas in the counties Dalarna and Jämtland County indicate that some stakeholders perceived that the process has so far not been inclusive.

- Produce knowledge about both ecological and social systems. Working with a learning organization with people who have relevant competence, awareness of what the organization works towards, and the ability to create teams. Provide support to local actors and work continuously with a broad perspective for analyses that thus become interesting for many actors and stakeholders. Prepare for the first meeting with the actors and stakeholders identified.

- Collaborate through dialogue and shared learning. Here, a process leader and tools for constructive dialogue, joint learning, negotiation, and agreements are needed. Collaboration is not about being completely in agreement, but about taking advantage of the differences that exist and learning from them, regardless of who carries the insight.

- Creating solutions and implementation. Implement agreements, organise management and care before a model for landscape planning through collaboration. Work continuously with planning, actions, and evaluation. Ongoing meetings are held for continuous learning by evaluating results and adapting future planning depending on the results achieved.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- European Commission. EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030: Bringing Nature Back Into Our Lives; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- D’Amato, D.; Droste, N.; Allen, B.; Kettunen, M.; Lähtinen, K.; Korhonen, J.; Leskinen, P.; Matthies, B.D.; Toppinen, A. Green, circular, bio economy: A comparative analysis of sustainability avenues. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 168, 716–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugge, M.M.; Hansen, T.; Klitkou, A. What Is the Bioeconomy? A Review of the Literature. Sustainability 2016, 8, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumayer, E. Weak Versus Strong Sustainability: Exploring the Limits of Two Opposing Paradigms; Edward Elgar Publishing: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Raworth, K. Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist; Chelsea Green Publishing: White River Junction, VT, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Shiller, R.J. Narrative Economics: How Stories Go Viral and Drive Major Economic Events; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Piketty, T. Capital and Ideology; Harvard University Press: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pülzl, H.; Kleinschmit, D.; Arts, B. Bioeconomy—An emerging meta-discourse affecting forest discourses? Scand. J. For. Res. 2014, 29, 386–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birner, R. Bioeconomy Concepts. In Bioeconomy: Shaping the Transition to a Sustainable, Biobased Economy, Lewandowski, I., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 17–38. [Google Scholar]

- Angelstam, P.; Manton, M.; Yamelynets, T.; Sørensen, O.J. Landscape approach towards integrated conservation and use of primeval forests: The transboundary Kovda River catchment in Russia and Finland. Land 2020, 9, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadows, D.H. Thinking in Systems: A Primer; Chelsea Green Publishing: White River Junction, VT, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, K.; Stenius, T.; Holmgren, S. Swedish Forests in the Bioeconomy: Stories from the National Forest Program. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2020, 33, 896–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobsson, R.; Olofsson, E.; Ambrose-Oji, B. Stakeholder perceptions, management and impacts of forestry conflicts in southern Sweden. Scand. J. For. Res. 2021, 36, 68–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelstam, P.; Manton, M.; Green, M.; Jonsson, B.-G.; Mikusiński, G.; Svensson, J.; Maria Sabatini, F. Sweden does not meet agreed national and international forest biodiversity targets: A call for adaptive landscape planning. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 202, 103838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullsten, O.; Angelstam, P.; Patel, A.; Rapport, D.J.; Cropper, A.; Pinter, L.; Washburn, M. Towards the Assessment of Environmental Sustainability in Forest Ecosystems: Measuring the Natural Capital. Ecol. Bull. 2004, 51, 471–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelstam, P.; Manton, M.; Elbakidze, M.; Sijtsma, F.; Adamescu, M.C.; Avni, N.; Beja, P.; Bezak, P.; Zyablikova, I.; Cruz, F.; et al. LTSER platforms as a place-based transdisciplinary research infrastructure: Learning landscape approach through evaluation. Landsc. Ecol. 2018, 34, 1461–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noss, R.F. Indicators for monitoring biodiversity: A hierarchical approach. Conserv. Biol. 1990, 4, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regeringen. Om en ny Skogspolitik. Proposition 1992/93:226. Sweden. 1993. Available online: https://data.riksdagen.se/fil/A0AE3402-7DB4-4E92-8B13-A24F1FD077EF (accessed on 10 March 2021).

- Regeringen. En svensk Strategi för Biologisk Mångfald och Ekosystemtjänster, Dated 2014-03-13. Regeringenskansliet: Stockholm, Sweden. 2014, p. 141. Available online: https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-lagar/dokument/proposition/en-svensk-strategi-for-biologisk-mangfald-och_H103141/html (accessed on 10 March 2021).

- CBD (Convention on Biological Diversity). The Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011–2020 and the Aichi Biodiversity Targets; Convention on Biological Diversity: Nagoya, Japan, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Our Life Insurance, Our Natural Capital: An EU Biodiversity Strategy to 2020; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Green Infrastructure (GI)—Enhancing Europe’s Natural Capital. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions; European Commission: Environment, Brussels, Belgium, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- SOU. Stärkt Äganderätt, Flexibla Skyddsformer och Naturvård i Skogen. Statens Offentliga Utredningar Stockholm, Sweden. 2020, p. 73. Available online: https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-lagar/dokument/statens-offentliga-utredningar/starkt-aganderatt-flexibla-skyddsformer-och_H8B373 (accessed on 10 March 2021).

- Segelbacher, G.; Höglund, J.; Storch, I. From connectivity to isolation: Genetic consequences of population fragmentation in capercaillie across Europe. Mol. Ecol. 2003, 12, 1773–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordén, J.; Åström, J.; Josefsson, T.; Blumentrath, S.; Ovaskainen, O.; Sverdrup-Thygeson, A.; Nordén, B. At which spatial and temporal scales can fungi indicate habitat connectivity? Ecol. Indic. 2018, 91, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrego, N.; Bässler, C.; Christensen, M.; Heilmann-Clausen, J. Implications of reserve size and forest connectivity for the conservation of wood-inhabiting fungi in Europe. Biol. Conserv. 2015, 191, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiegg, K. Effects of dead wood volume and connectivity on saproxylic insect species diversity. Écoscience 2000, 7, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truchy, A.; Sarremejane, R.; Muotka, T.; Mykrä, H.; Angeler, D.G.; Lehosmaa, K.; Huusko, A.; Johnson, R.K.; Sponseller, R.A.; McKie, B.G. Habitat patchiness, ecological connectivity and the uneven recovery of boreal stream ecosystems from an experimental drought. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2020, 26, 3455–3472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaitsev, A.S.; Gongalsky, K.B.; Persson, T.; Bengtsson, J. Connectivity of litter islands remaining after a fire and unburnt forest determines the recovery of soil fauna. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2014, 83, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hottola, J.; Ovaskainen, O.; Hanski, I. A unified measure of the number, volume and diversity of dead trees and the response of fungal communities. J. Ecol. 2009, 97, 1320–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahti, T.; Hämet-Ahti, L.; Jalas, J. Vegetation zones and their sections in northwestern Europe. Ann. Bot. Fenn. 1968, 169–211. [Google Scholar]

- Svensson, J.; Andersson, J.; Sandström, P.; Mikusiński, G.; Jonsson, B.G. Landscape trajectory of natural boreal forest loss as an impediment to green infrastructure. Conserv. Biol. 2019, 33, 152–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bladh, G. Finnskogens Landskap och Människor under Fyra Sekler. Forskningsrapport; Högskolan i Karlstad: Karlstad, Sweden, 1995; Volume 95, p. 11. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, G. Modern industriell framåtanda—Ett Nordiskt Exempel. Teknisk Tidskr. Kemi 1949, 11, 81–85. [Google Scholar]

- Lundmark, H. Clear-cutting—The most Discussed Logging Method in Swedish Forest History. Ph.D. Thesis, Sveriges lantbruksuniv, Uppsala, Sweden, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Von Sydow, U. Gräns för Storskalig Skogsbruk i Fjällnära Skogar–Förslag till Naturvårdsgräns; Svenska Naturskyddsföreningen (SNF): Stockholm, Sweden, 1988; p. 32. [Google Scholar]

- Jonsson, B.G.; Svensson, J.; Mikusiński, G.; Manton, M.; Angelstam, P. European Union’s Last Intact Forest Landscapes are at A Value Chain Crossroad between Multiple Use and Intensified Wood Production. Forests 2019, 10, 564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potapov, P.; Hansen, M.C.; Laestadius, L.; Turubanova, S.; Yaroshenko, A.; Thies, C.; Smith, W.; Zhuravleva, I.; Komarova, A.; Minnemeyer, S.; et al. The last frontiers of wilderness: Tracking loss of intact forest landscapes from 2000 to 2013. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1600821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindner, A.; Winberg, I.; Lindner, A. Flottgodsmängden i Norra Sveriges Allmänna Flottleder År 1930: Skala 1:1 000 000; A.B. Kartografiska institutet: Stockholm, Sweden, 1933. [Google Scholar]

- SLU. Forest Statistics 2020; Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU): Umeå, Sweden, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Henriksson, S.; Olsson, B.; Adolfsson, C. Skogar Med Höga Naturvärden Ovan Och i Nära Anslutning Till Fjällnära Gränsen—Statistik Ochsammanställning, Naturvårdsverket Rapport; Naturvårdsverket: Stockhlom, Sweden, 2020; p. 33. [Google Scholar]

- Angelstam, P.; Mikusinski, G.; Eriksson, J.A.; Jaxgård, P.; Kellner, O.; Koffman, A.; Ranneby, B.; Roberge, J.; Rosengren, M.; Rystedt, S.; et al. Analys Av Skogarna i Dalarnas Och Gävleborgs Län—Prioriteringsstöd Inför Områdesskydd; Länsstyrelsen Dalarnas län: Falun, Sweden, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Angelstam, P.; Andersson, K. Grön Infrastruktur för Biologisk Mångfald i Dalarna. Har Habitatnätverk för Barrskogsarter Förändrats 2002–2012? Länsstyrelsen Dalarnas län: Falun, Sweden, 2013. [Google Scholar]

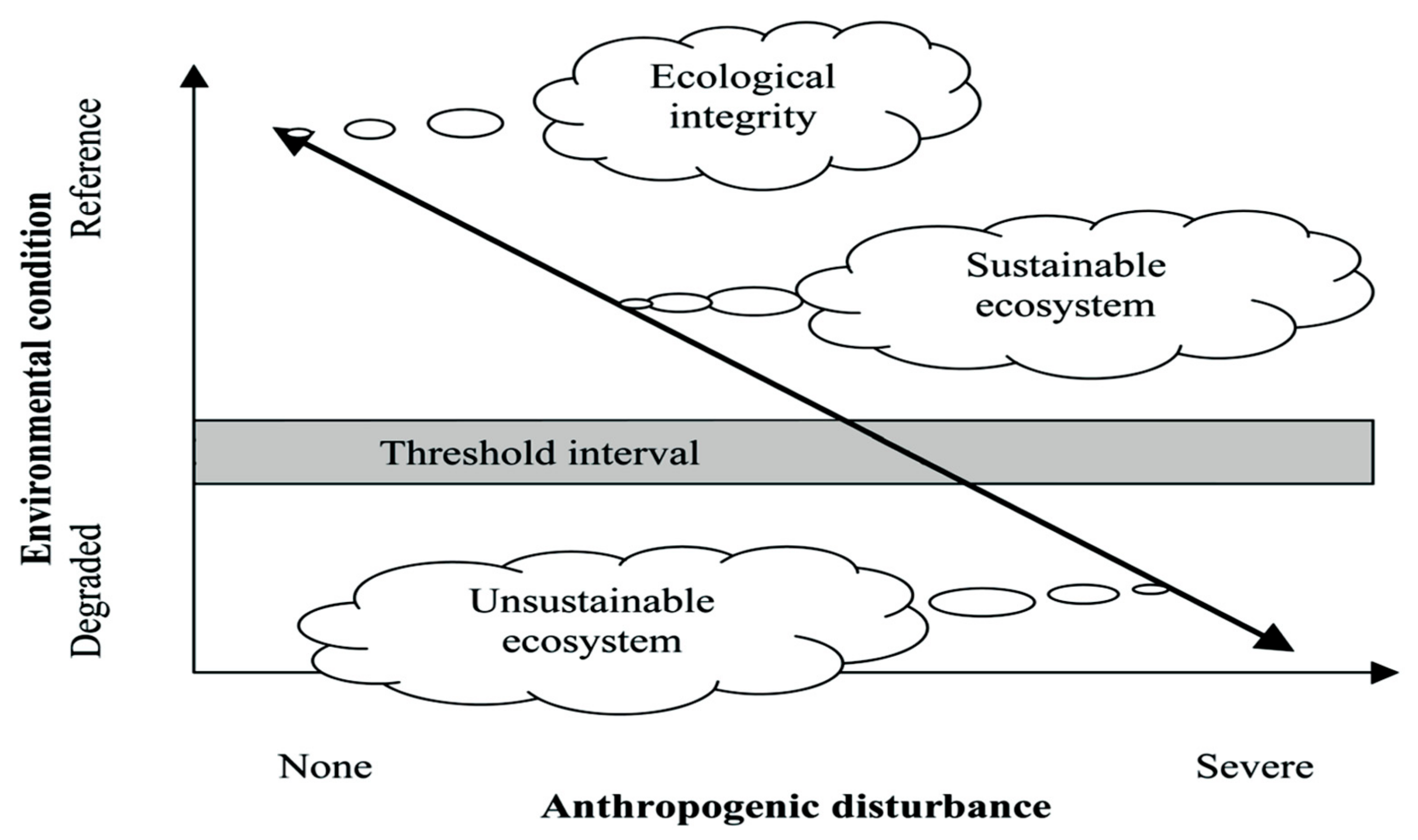

- Angelstam, P. Habitat thresholds and effects of forest landscape change on the distribution and abundance of Black Grouse and Capercaillie. Ecol. Bull. 2004, 51, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikars, L.-O. Habitat Requirements of the Pine Wood-Living Beetle Tragosoma depsarium (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) at Log, Stand, and Landscape Scale. Ecol. Bull. 2004, 51, 287–294. [Google Scholar]

- Jansson, G.; Andrén, H. Habitat Composition and Bird Diversity in Managed Boreal Forests. Scand. J. For. Res. 2003, 18, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bütler, R.; Angelstam, P.; Schlaepfer, R. Quantitative snag targets for the Three-Toed Woodpecker Picoides tridactylus. Ecol. Bull. 2004, 51, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindgren, P.; Olsson, P. Fungerande gröna infrastrukturer för skogslevande arter i Jämtlands län. In Rapport 1; Länsstyrelsen: Jämtland, Sweden, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- O’Toole, L.J., Jr. Research on Policy Implementation: Assessment and Prospects. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2000, 10, 263–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauschmayer, F.; Berghöfer, A.; Omann, I.; Zikos, D. Examining processes or/and outcomes? Evaluation concepts in European governance of natural resources. Environ. Policy Gov. 2009, 19, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelstam, P.; Andersson, L. Estimates of the needs for forest reserves in Sweden. Scand. J. For. Res. 2001, 16, 38–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wennberg, S.; Höjer, O. Frekvensanalys av Skyddsvärd Natur. Rapport 5466; Naturvårdsverket: Stockholm, Sweden, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Naturvårdsverket; Skogsstyrelsen. Nationell Strategi för Formellt Skydd av Skog. (Beslut Naturvårdsverkets dnr 310-419-04, Skogsstyrelsens dnr 194/04-4.43.); Naturvårdsverket: Stockholm, Sweden; Skogsstyrelsen: Stockholm, Sweden, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Naturvårdsverket; Skogsstyrelsen. Nationell Strategi för Formellt Skydd av Skog—Reviderad Version 2017. Rapport 6762; Naturvårdsverket: Stockholm, Sweden, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Felton, A.; Löfroth, T.; Angelstam, P.; Gustafsson, L.; Hjältén, J.; Felton, A.M.; Simonsson, P.; Dahlberg, A.; Lindbladh, M.; Svensson, J.; et al. Keeping pace with forestry: Multi-scale conservation in a changing production forest matrix. Ambio 2019, 49, 1050–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson, L.; Baker, S.C.; Bauhus, J.; Beese, W.J.; Brodie, A.; Kouki, J.; Lindenmayer, D.B.; Lõhmus, A.; Pastur, G.M.; Messier, C.; et al. Retention Forestry to Maintain Multifunctional Forests: A World Perspective. BioScience 2012, 62, 633–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson, L.; Bauhus, J.; Kouki, J.; Lõhmus, A.; Sverdrup-Thygeson, A. Retention forestry: An integrated approach in practical use. In Integrative Approaches as an Opportunity for the Conservation of Forest Biodiversity; Kraus, D., Krumm, F., Eds.; European Forest Institute: Freiburg, Germany, 2013; pp. 74–81. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, M.C.; Potapov, P.V.; Moore, R.; Hancher, M.; Turubanova, S.A.; Tyukavina, A.; Thau, D.; Stehman, S.V.; Goetz, S.J.; Loveland, T.R.; et al. High-resolution global maps of 21st-century forest cover change. Science 2013, 342, 850–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokland, J.N. The Coarse Woody Debris Profile: An Archive of Recent Forest History and an Important Biodiversity Indicator. Ecol. Bull. 2001, 49, 71–83. [Google Scholar]

- Angelstam, P.; Dönz-Breuss, M. Measuring forest biodiversity at the stand scale: An evaluation of indicators in European forest history gradients. Ecol. Bull. 2004, 51, 305–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsson, B.G.; Ekström, M.; Esseen, P.-A.; Grafström, A.; Ståhl, G.; Westerlund, B. Dead wood availability in managed Swedish forests—Policy outcomes and implications for biodiversity. For. Ecol. Manag. 2016, 376, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonsdale, D.; Pautasso, M.; Holdenrieder, O. Wood-decaying fungi in the forest: Conservation needs and management options. Eur. J. For. Res. 2008, 127, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, J.; Bütler, R. A review of habitat thresholds for dead wood: A baseline for management recommendations in European forests. Eur. J. For. Res. 2010, 129, 981–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelstam, P.; Roberge, J.-M.; Axelsson, R.; Elbakidze, M.; Bergman, K.-O.; Dahlberg, A.; Degerman, E.; Eggers, S.; Esseen, P.-A.; Hjältén, J.; et al. Evidence-Based Knowledge Versus Negotiated Indicators for Assessment of Ecological Sustainability: The Swedish Forest Stewardship Council Standard as a Case Study. Ambio 2013, 42, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Angelstam, P.K.; Bütler, R.; Lazdinis, M.; Mikusiński, G.; Roberge, J.-M. Habitat thresholds for focal species at multiple scales and forest biodiversity conservation; dead wood as an example. Ann. Zool. Fenn. 2003, 40, 473–482. [Google Scholar]

- Roberge, J.-M.; Angelstam, P.; Villard, M.-A. Specialised woodpeckers and naturalness in hemiboreal forests—Deriving quantitative targets for conservation planning. Biol. Conserv. 2008, 141, 997–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edman, T.; Angelstam, P.; Mikusiński, G.; Roberge, J.-M.; Sikora, A. Spatial planning for biodiversity conservation: Assessment of forest landscapes’ conservation value using umbrella species requirements in Poland. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2011, 102, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikusiński, G.; Edenius, L. Assessment of spatial functionality of old forest in Sweden as habitat for virtual species. Scand. J. For. Res. 2006, 21, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manton, M.; Angelstam, P.; Mikusiński, G. Modelling habitat suitability for deciduous forest focal species—A sensitivity Analysis using different satellite Land cover data. Landsc. Ecol 2005, 20, 827–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelstam, P.; Roberge, J.M.; Lõhmus, A.; Bergmanis, M.; Brazaitis, G.; Dönz-Breuss, M.; Edenius, L.; Kosinski, Z.; Kurlavicius, P.; Lārmanis, V.; et al. Habitat modelling as a tool for landscape-scale conservation: A review of parameters for focal forest birds. Ecol. Bull. 2004, 51, 427–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergstedt, J. Projektet Grön Infrastruktur i Gåsbergets Värdetrakt; Rapport; Länsstyrelsen i Dalarna: Dalarna, Falun, 2019; p. 28. [Google Scholar]

- Länsstyrelsen. Regional Strategi för Formellt Skydd av Skog i Dalarnas län—Revideringsarbetet 2018; Länsstyrelsen i Dalarnas län: Dalarna, Sweden, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kirppu, S.; Oldhammer, B. Ore skogsrike. Ett Levande Skogslandskap i Rättviks Kommun; Naturskyddsföreningen och Rättviks kommun: Rättviks, Sweden, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kirppu, S.; Björnström, H.; Oldhammer, B. Ändå Hugger Man. Rapport Från Ore Skogsrike 2017 Med en Analys av Sveaskogs Naturvårdsambitioner; Naturskyddsföreningen Rättvik: Rättvik, Sweden, 2017; p. 79. [Google Scholar]

- Berglund, H.; Kuuluvainen, T. Representative boreal forest habitats in northern Europe, and a revised model for ecosystem management and biodiversity conservation. Ambio 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajek, F. Mapping of lntact Forest Landscapes in Sweden according to Global Forest Watch Methodology; Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU): Uppsala, Sweden, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Yaroshenko, A.; Potapov, P.; Turubanova, S. The Last Intact Forest Landscapes of Northern European Russia; Greenpeace Russia and Global Forest Watch: Moscow, Russia, 2001; Volume 93. [Google Scholar]

- Kirppu, S.; von Sydow, U. Forskningsresan i Naturvårdens Utmarker; Naturskyddsföreningen and Skydda Skogen: Jämtland, Sweden, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Balanskommissionen. Balanskommissionens hinderrapport. Står Miljölagstiftningen i Vägen för att Bygga Detnya Hållbara Sverige? [Report about obstacles, Is the Environmental Legislation in the Way for Building the New Sustainable Sweden?]. Balanskommissionen: Sweden, 2019. Available online: https://balanskommissionen.se/app/uploads/2019/08/Balanskommissionen_Hinderrapporten-1.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2021).

- Fischer, A.P. Forest landscapes as social-ecological systems and implications for management. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 177, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manton, M.; Angelstam, P. Defining Benchmarks for Restoration of Green Infrastructure: A Case Study Combining the Historical Range of Variability of Habitat and Species’ Requirements. Sustainability 2018, 10, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knize, A.; Romanyuk, B. Two Opinions of Russia’s Forest and Forestry; WWF: Moscow, Russia, 2006; p. 26. [Google Scholar]

- Messier, C.; Puettmann, K.; Chazdon, R.; Andersson, K.P.; Angers, V.A.; Brotons, L.; Filotas, E.; Tittler, R.; Parrott, L.; Levin, S.A. From Management to Stewardship: Viewing Forests as Complex Adaptive Systems in an Uncertain World. Conserv. Lett. 2015, 8, 368–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senf, C.; Seidl, R. Mapping the forest disturbance regimes of Europe. Nat. Sustain. 2021, 4, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelstam, P.; Manton, M.; Yamelynets, T.; Fedoriak, M.; Albulescu, A.-C.; Bravo, F.; Cruz, F.; Jaroszewicz, B.; Kavtarishvili, M.; Muñoz-Rojas, J.; et al. Maintaining natural and traditional cultural green infrastructures across Europe: Learning from historic and current landscape transformations. Landsc. Ecol 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, J. The Forgotten Forest: On Thinning, Retention, and Biodiversity in the Boreal Forest; Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences: Uppsala, Sweden, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Picard, N.; Leban, J.-M.; Guehl, J.-M.; Dreyer, E.; Bouriaud, O.; Bontemps, J.-D.; Landmann, G.; Colin, A.; Peyron, J.-L.; Marty, P. Recent increase in European forest harvests as based on area estimates (Ceccherini et al. 2020a) not confirmed in the French case. Ann. For. Sci. 2021, 78, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisse, M.; Potapov, P. Assessing Trends in Tree Cover Loss Over 20 Years of Data. Available online: https://www.globalforestwatch.org/blog/data-and-research/tree-cover-loss-satellite-data-trend-analysis/ (accessed on 3 May 2021).

- Breidenbach, J.; Ellison, D.; Petersson, H.; Korhonen, K.; Henttonen, H.; Wallerman, J.; Fridman, J.; Gobakken, T.; Astrup, R.; Næsset, E. No “Abrupt increase in harvested forest area over Europe after 2015”–How the misuse of a satellite-based map led to completely wrong conclusions. In Proceedings of the Copernicus Meetings, 19–30 April 2021; Available online: https://meetingorganizer.copernicus.org/EGU21/EGU21-13243.html (accessed on 30 April 2021).

- Palahí, M.; Valbuena, R.; Senf, C.; Acil, N.; Pugh, T.A.M.; Sadler, J.; Seidl, R.; Potapov, P.; Gardiner, B.; Hetemäki, L.; et al. Concerns about reported harvests in European forests. Nature 2021, 592, E15–E17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceccherini, G.; Duveiller, G.; Grassi, G.; Lemoine, G.; Avitabile, V.; Pilli, R.; Cescatti, A. Abrupt increase in harvested forest area over Europe after 2015. Nature 2020, 583, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eyvindson, K.; Repo, A.; Mönkkönen, M. Mitigating forest biodiversity and ecosystem service losses in the era of bio-based economy. For. Policy Econ. 2018, 92, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, J.E.; Venter, O.; Lee, J.; Jones, K.R.; Robinson, J.G.; Possingham, H.P.; Allan, J.R. Protect the Last of the Wild. Nature 2018, 563, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, M.; Saura, S.; Williams, B.; Ramírez-Delgado, J.P.; Arafeh-Dalmau, N.; Allan, J.R.; Venter, O.; Dubois, G.; Watson, J.E.M. Just ten percent of the global terrestrial protected area network is structurally connected via intact land. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuuluvainen, T.; Angelstam, P.; Frelich, L.; Jõgiste, K.; Koivula, M.; Kubota, Y.; Lafleur, B.; MacDonald, E. Natural disturbance-based forest management: Moving beyond retention and continuous-cover forestry. Front. For. Glob. Chang. 2021, 4, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuuluvainen, T.; Lindberg, H.; Vanha-Majamaa, I.; Keto-Tokoi, P.; Punttila, P. Low-level retention forestry, certification, and biodiversity: Case Finland. Ecol. Process. 2019, 8, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahrig, L. Effects of habitat fragmentation on biodiversity. Ann. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2003, 34, 487–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelsson, R.; Angelstam, P.; Elbakidze, M.; Stryamets, N.; Johansson, K.-E. Sustainable development and sustainability: Landscape approach as a practical interpretation of principles and implementation concepts. J. Landsc. Ecol. 2011, 4, 5–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelsson, R.; Angelstam, P.; Degerman, E.; Teitelbaum, S.; Andersson, K.; Elbakidze, M.; Drotz, M. Social and cultural sustainability: Criteria, indicators, verifier variables for measurement and maps for visualization to support planning. Ambio 2013, 42, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angelstam, P.; Munoz-Rojas, J.; Pinto-Correia, T. Landscape concepts and approaches foster learning about ecosystem services. Landsc. Ecol. 2019, 34, 1445–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrini-Feyerabend, G.; Pimbert, M.; Farvar, M.; Kothari, A.; Renard, Y. Sharing Power. Learning-by-Doing in Co-Management of Natural Resources throughout the World; Cenesta: Tehran, Iran, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Barbour, M. Ecological Assessment of Aquatic Resources: Linking Science to Decision-Making; SETAC Press: Pensacola, FL, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Heo, S.; Lim, C.C.; Bell, M.L. Relationships between Local Green Space and Human Mobility Patterns during COVID-19 for Maryland and California, USA. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelstam, P.; Fedoriak, M.; Cruz, F.; Muñoz-Rojas, J.; Yamelynets, T.; Manton, M.; Washbourne, C.-L.; Dobrynin, D.; Izakovičova, Z.; Jansson, N.; et al. Meeting places and social capital supporting rural landscape stewardship: A Pan-European horizon scanning. Ecol. Soc. 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rummukainen, M. Skogens klimatnyttor—En balansakt i prioritering. In CEC Rapport Nr 6; Lunds Universitet, Centrum för miljö- och klimatvetenskap: Lund, Sweden, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Harmon, M.E. Have product substitution carbon benefits been overestimated? A sensitivity analysis of key assumptions. Environ. Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 065008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buotte, P.C.; Law, B.E.; Ripple, W.J.; Berner, L.T. Carbon sequestration and biodiversity co-benefits of preserving forests in the western United States. Ecol. Appl. 2020, 30, e02039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinerstein, E.; Joshi, A.R.; Vynne, C.; Lee, A.T.L.; Pharand-Deschênes, F.; França, M.; Fernando, S.; Birch, T.; Burkart, K.; Asner, G.P.; et al. A “Global Safety Net” to reverse biodiversity loss and stabilize Earth’s climate. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eabb2824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggestam, F.; Giurca, A. The art of the “green” deal: Policy pathways for the EU Forest Strategy. For. Policy Econ. 2021, 128, 102456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedung, E. Policy instruments: Typologies and theories. In Carrots, Sticks, and Sermons: Policy Instruments and Their Evaluation; Bemelmans-Videc, M.L., Rist, R.C., Vedung, E.O., Eds.; Transaction Publishers: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 1998; Volume 5, pp. 21–58. [Google Scholar]

| Forest and Land Cover Type | Dalarna | Jämtland | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion of productive forest area (%) | Scots pine | 58.7 | 33.3 |

| Norway spruce | 17.3 | 34.8 | |

| Exotics | 1 | 7.7 | |

| Mixed coniferous mix | 12.6 | 11 | |

| Conifer/broadleaf mix | 3.6 | 7.6 | |

| Deciduous | 3.9 | 3.8 | |

| Bare | 2.9 | 2.8 | |

| Total area productive forest area (1000 ha) | Total | 1873 | 2549 |

| (1978 *) | (2689 *) | ||

| Proportion of traditional land use classes (2015–2019) | Productive forest land * | 70.2 | 54.8 |

| Pasture land | 0.3 | 0.2 | |

| Arable land | 2.7 | 0.8 | |

| Mire | 16.1 | 16.6 | |

| Rock surface | 0.6 | 1 | |

| Subalpine woodland | 3.2 | 7.3 | |

| Alpine area | 2.8 | 17 | |

| Urban land | 2.3 | 0.7 | |

| Other land | 1.9 | 1.5 | |

| Total land area (1000 ha) | 2819 | 4905 |

| Indicator | Verifier Variable | Sources | |

|---|---|---|---|

| The production landscape matrix managed for high sustained yield of industrial raw material | Pressure through loss of older forest | Yearly data and maps for four 5-year periods for two data sets | Hansen et al. “forest loss” data (2001–2019) Forest Agency borders of fellings 1998–2019 |

| Effect on the stand age distribution | Changes in the two counties | NFI 1955–2017 | |

| Effect of dead wood in the entire forest landscape | Changes in the amount of dead wood in Sweden | Jonsson et al. (2016), 1994–2012) and updated with one more NFI survey period (2012–2016) | |

| Conservation areas | Response through the creation of different categories of protected areas | Changes over time in the two counties | Swedish Environmental Protection Agency |

| Effect on High Conservation Value Forests forming green infrastructures | Changes in functional connectivity 2002–2012, for the 2000–2019 period, and divided into spruce and pine | Angelstam and Andersson (2013), Lindgren and Olofsson (2019) (kNN for 2000 minus clearcuts 2000–2019), | |

| Effect on retention of trees and dead wood on harvested areas | Changes in the amounts of live trees and standing and lying dead wood | Swedish Forest Agency Statistics from 1994/95 to 2010/11 |

| Forest Type | Focal Species | Patch Requirements | Buffer | Home Range (km2) | Threshold (Required Habitat) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Old spruce > 70 | Picoides tridactylus | 10 ha | 25 m | 4 | 25% |

| Resident passerine birds | 20 ha | 25 m | 1 | 60% | |

| Old pine > 70 | Tragosoma depsarium | 10 ha (<400 m a.s.l. *) | 0 m | 25 | 25% |

| Tetrao urogallus | 200 ha | 100 m | 16 | 25% |

| Scots Pine | Norway Spruce | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tetrao urogallus | Tragosoma depsarium | Picoides tridactylus | Resident Passerine Birds | |||||

| Dalarna | Jämtland | Dalarna | Jämtland | Dalarna | Jämtland | Dalarna | Jämtland | |

| All forest >70 years | 271,356 | 243,958 | 168,540 | 135,667 | 93,483 | 355,921 | 93,483 | 355,921 |

| Stands | 264,061 | 225,146 | 61,586 | 46,941 | 55,374 | 292,313 | 41,870 | 260,077 |

| Tracts | 42,282 | 25,661 | 2744 | 1506 | 7451 | 86,084 | 907 | 14,673 |

| Dalarna County Gåsberget * (“Ore Skogsrike”) | Jämtland County Björkvattnet | |

|---|---|---|

| Area (ha) | Ca. 40,000 | Ca. 70,000 |

| Forest proportion (%) | 82 | 41 |

| pCF forest(%) | 36 | 32 |

| Core area (%) | 27 | 30 |

| Forest types | Forest fire in 1888 created a rare example of multi-cohort Scots pine and late deciduous forest succession | Old-growth spruce, border mountain birch |

| Formal protection (%) | 5 | 0 |

| Voluntary set-asides (%) | 16 | NA |

| Other and uncertain (%) | 7 | NA |

| Forest ownership | NIPF (17%), industry (83%) | NIPF (58%), industry (42%) |

| Final felling rate (%/year) | 1.1 (0.4–1.8) | a passing frontier |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Angelstam, P.; Manton, M. Effects of Forestry Intensification and Conservation on Green Infrastructures: A Spatio-Temporal Evaluation in Sweden. Land 2021, 10, 531. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10050531

Angelstam P, Manton M. Effects of Forestry Intensification and Conservation on Green Infrastructures: A Spatio-Temporal Evaluation in Sweden. Land. 2021; 10(5):531. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10050531

Chicago/Turabian StyleAngelstam, Per, and Michael Manton. 2021. "Effects of Forestry Intensification and Conservation on Green Infrastructures: A Spatio-Temporal Evaluation in Sweden" Land 10, no. 5: 531. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10050531

APA StyleAngelstam, P., & Manton, M. (2021). Effects of Forestry Intensification and Conservation on Green Infrastructures: A Spatio-Temporal Evaluation in Sweden. Land, 10(5), 531. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10050531