Children’s Rights in the Indonesian Oil Palm Industry: Improving Company Respect for the Rights of the Child

Abstract

1. Introduction

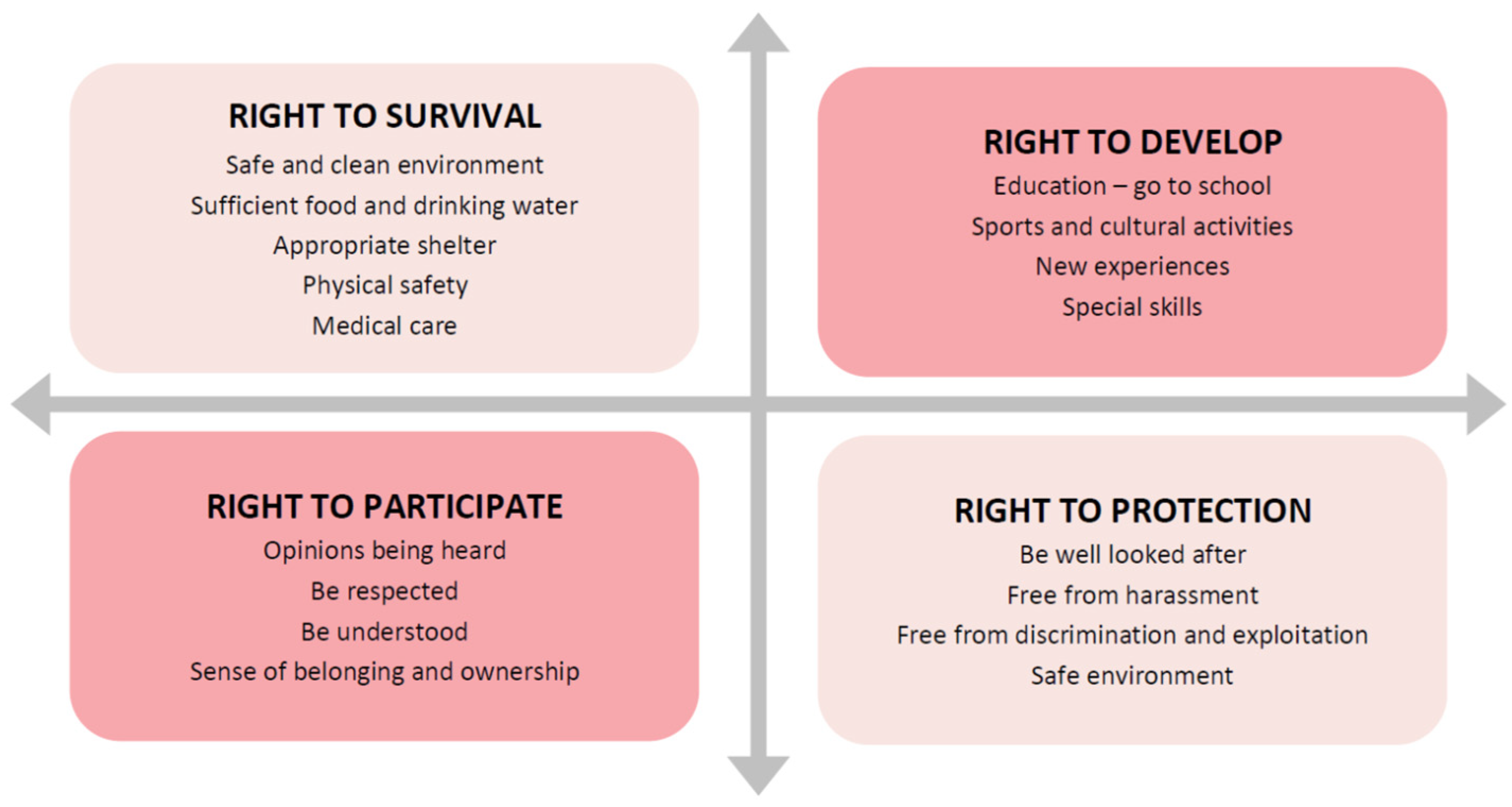

2. What Are Company Obligations to Respect Children’s Rights?

3. What Companies Should Do to Respect Children’s Rights in Practice

4. Methodology

5. Overall Assessment of the Two Programs

6. Respecting Children’s Rights in Practice

7. Discussion: Issues That Arise from Respecting Children’s Rights in Practice

7.1. Getting Company Commitments to Children’s Rights into Policy and Practice

7.2. Having a Strong Business Case for Respecting Children’s Rights

7.3. Contradictory Objectives within Companies

7.4. Complexities around Children in the Workplace

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNICEF. Palm Oil and Children in Indonesia: Exploring the Sector’s Impact on Children’s Rights; UNICEF: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2016; Available online: https://www.unicef.org/indonesia/media/1876/file/Palm%20oil%20and%20children%20in%20Indonesia.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- RSPO. Children’s Rights in RSPO Member Oil Palm Plantations in Indonesia; Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2019; Available online: https://www.rspo.org/resources/archive/892 (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- Collins, T. The relationship between children’s rights and business. Int. J. Hum. Rights 2014, 18, 582–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, J. Children’s Rights: Today’s Global Challenge; Rowman & Littlefield: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Amnesty International. The Great Palm Oil Scandal: Labour Abuses behind Big Brand Names; Amnesty International: London, UK, 2016; Available online: https://www.amnesty.org/download/Documents/ASA2151842016ENGLISH.PDF (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- International Labour Organization. Child Labour in Plantation. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/jakarta/areasofwork/WCMS_126206/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- Gottwald, E. Certifying exploitation: Why ‘sustainable’ palm oil production is failing workers. New Labor Forum 2018, 27, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teoh, C.H. Key Sustainability Issues in the Palm Oil Sector: A Discussion Paper for Multi-Stakeholders Consultations; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2010; Available online: http://www.biofuelobservatory.org/Documentos/Otros/Palm-Oil-Discussion-Paper-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- ECOSOC. Palm Oil Industry and Human Rights: A Case Study on Oil Palm Corporations in Central Kalimantan; Institute for Economic, Social and Cultural Rights: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2015; Available online: https://www.jus.uio.no/smr/english/about/programmes/indonesia/docs/report-english-version-jan-2015.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- Vanclay, F. Conceptualising social impacts. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2002, 22, 183–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanclay, F. Principles to gain a social licence to operate for green initiatives and biodiversity projects. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2017, 29, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanclay, F. Project-induced displacement and resettlement: From impoverishment risks to an opportunity for development? Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2017, 35, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyth, E.; Vanclay, F. The Social Framework for Projects: A conceptual but practical model to assist in assessing, planning and managing the social impacts of projects. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2017, 35, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogwang, T.; Vanclay, F. Cut-off and forgotten?: Livelihood disruption, social impacts and food insecurity arising from the East African Crude Oil Pipeline. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 71, 101970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatto, M.; Wollni, M.; Qaim, M. Oil palm boom, contract farming, and rural economic development: Village-level evidence from Indonesia. World Dev. 2017, 95, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qaim, M.; Sibhatu, K.; Siregar, H.; Grass, I. Environmental, economic, and social consequences of the oil palm boom. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 2020, 12, 321–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF. Children Are Everyone’s Business Workbook 2.0: A Guide for Integrating Children’s Rights into Policies, Impact Assessments and Sustainability Reporting; UNICEF: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014; Available online: https://www.unicef.org/csr/css/Workbook_2.0_Second_Edition_29092014_LR.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- Paré, M.; Chong, T. Human rights violations and Canadian mining companies: Exploring access to justice in relation to children’s rights. Int. J. Hum. Rights 2017, 21, 908–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RSPO. Research Brief: Palm Oil Business Operations’ Impact on Children’s Rights; Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2019; Available online: https://www.rspo.org/resources/archive/1126 (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- Esteves, A.M.; Vanclay, F. Social Development Needs Analysis as a tool for SIA to guide corporate-community investment: Applications in the minerals industry. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2009, 29, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, D.; Vanclay, F. Human rights and impact assessment: Clarifying the connections in practice. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2013, 31, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Ploeg, L.; Vanclay, F. A tool for improving the management of social and human rights risks at project sites: The Human Rights Sphere. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 4072–4084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Ploeg, L.; Vanclay, F. A human rights based approach to project-induced displacement and resettlement. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2017, 35, 34–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Ploeg, L.; Vanclay, F. Challenges in implementing the corporate responsibility to respect human rights in the context of project-induced displacement and resettlement. Resour. Policy 2018, 55, 210–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggie, J.G. Just Business: Multinational Corporations and Human Rights; Norton: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Berlan, A. Whose business is it anyway? Children and corporate social responsibility in the international business agenda. Child. Soc. 2016, 30, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijaard, E.; Sheil, D. The moral minefield of ethical oil palm and sustainable development. Front. For. Glob. Chang. 2019, 2, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, T. Children’s rights in HRIA: Marginalized or mainstreamed? In Handbook on Human Rights Impact Assessment; Götzmann, N., Ed.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2019; pp. 119–134. [Google Scholar]

- Turkelli, G.E. Children’s Rights and Business: Governing Obligations and Responsibility; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wilcove, D.; Koh, L. Addressing the threats to biodiversity from oil-palm agriculture. Biodivers. Conserv. 2010, 19, 999–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aulia, A.F.; Sandhu, H.; Millington, A.C. Quantifying the economic value of ecosystem services in oil palm dominated landscapes in Riau Province in Sumatra, Indonesia. Land 2020, 9, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayompe, L.; Schaafsma, M.; Egoh, B. Towards sustainable palm oil production: The positive and negative impacts on ecosystem services and human wellbeing. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 278, 123914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil. Available online: https://rspo.org/ (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- Schouten, G.; Glasbergen, P. Creating legitimacy in global private governance: The case of the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil. Ecol. Econ. 2011, 70, 1891–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RSPO. Principles and Criteria for the Production of Sustainable Palm Oil; Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2020; Available online: https://www.rspo.org/resources/archive/1079 (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- Forest Conservation Policy. Golden Agri-Resources. 2011. Available online: https://goldenagri.com.sg/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/1._GAR_Forest_Conservation_Policy_-_updated_links_10_Jan_2014.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- Wilmar. No Deforestation, No Peat, No Exploitation Policy; Wilmar International: Singapore, 2013; Available online: https://www.wilmar-international.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/No-Deforestation-No-Peat-No-Exploitation-Policy.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- Wilmar. Wilmar International Sustainability Report 2013: Transformation through Engagement; Wilmar International: Singapore, 2013; Available online: https://www.wilmar-international.com/sustainability/wp-content/themes/wilmar/sustainability/assets/Wilmar%20Sustainability%20Report%202013%20-%20Final%20(low-res).pdf (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- Wilmar. No Deforestation, No Peat, No Exploitation Policy; Updated November 2019; Wilmar International: Singapore, 2019; Available online: https://www.wilmar-international.com/docs/default-source/default-document-library/sustainability/policies/wilmar-ndpe-policy---2019.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- Proforest. Understanding Commitments to No Deforestation, No Peat and No Exploitation (NDPE). Proforest. 2020. Available online: https://proforest.net/proforest/en/publications/infonote_04_introndpe.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- Colchester, M. Palm Oil and Indigenous Peoples in South East Asia. The International Land Coalition. 2011. Available online: http://www.forestpeoples.org/sites/fpp/files/publication/2010/08/palmoilindigenouspeoplesoutheastasiafinalmceng_0.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- Li, T.M. Social Impacts of Oil Palm in Indonesia: A Gendered Perspective from West Kalimantan; CIFOR: Bogor, Indonesia, 2015; Available online: https://www.cifor.org/publications/pdf_files/OccPapers/OP-124.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- Andrianto, A.; Komarudin, H.; Pacheco, P. Expansion of oil palm plantations in Indonesia’s frontier: Problems of externalities and the future of local and Indigenous communities. Land 2019, 8, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santika, T.; Wilson, K.; Budiharta, S.; Law, E.; Poh, T.; Ancrenaz, M.; Struebig, M.; Meijaard, E. Does oil palm agriculture help alleviate poverty? A multidimensional counterfactual assessment of oil palm development in Indonesia. World Dev. 2019, 120, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santika, T.; Wilson, K.; Meijaard, E.; Budiharta, S.; Law, E.; Sabri, M.; Struebig, M.; Ancrenaz, M.; Poh, T. Changing landscapes, livelihoods and village welfare in the context of oil palm development. Land Use Policy 2019, 87, 104073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasaribu, S.; Vanclay, F.; Zhao, Y. Challenges to implementing Socially-Sustainable Community Development in oil palm and forestry operations in Indonesia. Land 2020, 9, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasaribu, S.I.; Vanclay, F.; Holzhacker, R. The governance of Social Licence to Operate in the forest industry in Indonesia: The perspectives of the multiple stakeholders. In Challenges of Governance: Development and Regional Integration in Southeast Asia and ASEAN; Holzhacker, R., Tan, W., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 209–226. [Google Scholar]

- Rival, A.; Levang, P. Palms of Controversies: Oil Palm and Development Challenges; CIFOR: Bogor, Indonesia, 2014; Available online: https://www.cifor.org/publications/pdf_files/Books/BLevang1401.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- Vanclay, F.; Hanna, P. Conceptualising company response to community protest: Principles to achieve a social license to operate. Land 2019, 8, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, P.; Vanclay, F. Human rights, Indigenous peoples and the concept of Free, Prior and Informed Consent. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2013, 31, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodhouse, T.; Vanclay, F. Is Free, Prior and Informed Consent a form of Corporate Social Responsibility? J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 131, 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteves, A.M.; Factor, G.; Vanclay, F.; Götzmann, N.; Moreiro, S. Adapting social impact assessment to address a project’s human rights impacts and risks. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2017, 67, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busscher, N.; Parra, C.; Vanclay, F. Land grabbing within a protected area: The experience of local communities with conservation and forestry activities in Los Esteros del Iberá, Argentina. Land Use Policy 2018, 78, 572–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busscher, N.; Vanclay, F.; Parra, C. Reflections on how state-civil society collaborations play out in the context of land grabbing in Argentina. Land 2019, 8, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busscher, N.; Parra, C.; Vanclay, F. Environmental justice implications of land grabbing for industrial agriculture and forestry in Argentina. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2020, 63, 500–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Labour Organization. C138 Minimum Age Convention, 1973 (No. 138). Available online: https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_ilo_code:C138 (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- International Labour Organization. C182 Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention, 1999 (No. 182). Available online: https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_ILO_CODE:C182 (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 1989; Available online: https://www.unicef.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/unicef-convention-rights-child-uncrc.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- General Comment No. 16 (2013) on State Obligations Regarding the Impact of the Business Sector on Children’s Rights. Committee on the Rights of the Child. United Nations Document Number: CRC/C/GC/16. 2013. Available online: https://www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/crc/docs/CRC.C.GC.16.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- Van Alstine, J.; Barkemeyer, R. Business and development: Changing discourses in the extractive industries. Resour. Policy 2014, 40, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF. The State of the World’s Children Special Edition: Celebrating 20 Years of the Convention on the Rights of the Child; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2009; Available online: https://sites.unicef.org/rightsite/sowc/pdfs/SOWC_Spec%20Ed_CRC_Main%20Report_EN_090409.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- UNICEF. Implementation Handbook for The Convention on the Rights of the Child, 3rd ed.; UNICEF Regional Office for Europe: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007; Available online: https://www.unicef.org/Implementation_Handbook_for_the_Convention_on_the_Rights_of_the_Child.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- UNICEF. Children’s Rights and Business Principles. UNICEF, Save the Children, UN Global Compact. 2012. Available online: https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/node/5717/pdf/5717.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- United Nations. The Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights: Implementing the United Nations ‘Protect, Respect and Remedy Framework’; HR/PUB/11/04; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2011; Available online: http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Publications/GuidingPrinciplesBusinessHR_EN.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- Global Compact. A Guide for Integrating Human Rights into Business Management; United Nations Global Compact: London, UK, 2006; Available online: https://www.unglobalcompact.org/library/13 (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- UNICEF. Children’s Rights in Impact Assessments: A Guide for Integrating Children’s Rights into Impact Assessments and Taking Action for Children. The Danish Institute for Human Rights, UNICEF. 2013. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/csr/css/Children_s_Rights_in_Impact_Assessments_Web_161213.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- UNICEF. Child Safeguarding Toolkit for Business: A Step-by-Step to Identifying and Preventing Risks to Children Who Interact with Your Business; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2018; Available online: https://www.unicef.org/csr/files/UNICEF_ChildSafeguardingToolkit_FINAL.PDF (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- Save the Children. How to Use the Children’s Rights and Business Principles: A Guide for Civil Society Organizations; Save the Children: Stockholm, Sweden, 2014; Available online: https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/sites/default/files/documents/crbp-guide_final_cs5_ny_2.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- Kappell, A.; Wilson, J. Business and Children’s Participation: How Businesses Can Create Opportunities for Children’s Participation; Save the Children: Stockholm, Sweden, 2015; Available online: https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/node/8854/pdf/business-and-child-participation_hn.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- Global Child Forum. How to Implement a Children’s Rights Perspective; Global Child Forum: Stockholm, Sweden, 2020; Available online: https://www.globalchildforum.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Business-workbook-2020_edited.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- Earthworm Foundation. Guideline for Indonesian Palm Oil Companies: Mitigating the Risks of Child Labour in Oil Palm Plantations; Earthworm Foundation: Nyon, Switzerland, 2020; Available online: https://www.earthworm.org/uploads/files/Guideline-Mitigating-the-Risks-of-Child-Labour.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- WHO. INSPIRE Handbook: Action for Implementing the Seven Strategies for Ending Violence against Children; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/inspire-handbook-action-forimplementing-the-seven-strategies-for-ending-violence-against-children (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- RSPO. Guidance on Child Rights for Palm Oil Producers; Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2020; Available online: https://rspo.org/library/lib_files/preview/1404 (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- CRIN. Indonesia: National Laws; Child Rights International Network: London, UK, 2013; Available online: https://archive.crin.org/en/library/publications/indonesia-national-laws.html (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- USDOL. Child Labor and Forced Labor Reports: Indonesia; United States Department of Labor: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. Available online: https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/ILAB/child_labor_reports/tda2019/Indonesia.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- Save the Children. Review Report The Implementation of Convention on the Rights of the Child in Indonesia 1997–2009; Save the Children: Stockholm, Sweden, 2010; Available online: https://tbinternet.ohchr.org/Treaties/CRC/Shared%20Documents/IDN/INT_CRC_ICO_IDN_15725_E.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- Ijabadeniyi, A.; Vanclay, F. Socially-tolerated practices in Environmental and Social Impact Assessment reporting: Discourses, displacement, and impoverishment. Land 2020, 9, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafner-Burton, E.; Tsutsui, K. Human rights in a globalizing world: The paradox of empty promises. Am. J. Sociol. 2005, 110, 1373–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evanty, N.; Ghufron, N. Multinational corporations and human rights in Indonesia: The need for improvement in legislation. In Business and Human Rights in Asia: Duty of the State to Protect; Gomez, J., Ramcharan, R., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Singapore, 2021; pp. 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ILO. Child Labour: A Textbook for University Students; International Labour Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004; Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_norm/documents/publication/wcms_067258.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- ILO. ILO Convention No. 138 at a Glance; International Labour Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; Available online: https://www.ilo.org/ipecinfo/product/download.do?type=document&id=30215 (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- Proforest. Drivers of Child Labour, Forced Labour, Inadequate Health and Safety, and Land Rights Abuses and Disputes in Agriculture and Forestry; Proforest: Oxford, UK, 2019; Available online: https://www.proforest.net/fileadmin/uploads/proforest/Documents/Publications/infonote_drivers-of-child-labour_web-2.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- Collins, T.; Guevara, G. Some considerations for Child Rights Impact Assessment (CRIAs) of business. Rev. Générale Droit 2014, 44, 153–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. The Corporate Responsibility to Respect Human Rights: An Interpretive Guide; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2012; Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Publications/HR.PUB.12.2_En.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- Götzmann, N.; Vanclay, F.; Seier, F. Social and human rights impact assessment: What can they learn from each other? Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2016, 34, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, C.; Dhanarajan, S. The corporate responsibility to respect human rights: A status review. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2016, 29, 542–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF. Children’s Rights in the Mining Sector: UNICEF Extractive Pilot; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: https://www.unicef.org/csr/files/UNICEF_REPORT_ON_CHILD_RIGHTS_AND_THE_MINING_SECTOR_APRIL_27.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- BSR. Conducting an Effective Human Rights Impact Assessment: Guidelines, Steps, and Examples; Business for Social Responsibility: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2013; Available online: https://www.bsr.org/reports/BSR_Human_Rights_Impact_Assessments.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- Hanna, P.; Vanclay, F.; Langdon, E.J.; Arts, J. Conceptualizing social protest and the significance of protest action to large projects. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2016, 3, 217–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W. A makeover for the world’s most hated crop. Nature 2017, 543, 306–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharmawan, A.H.; Mardiyaningsih, D.I.; Komarudin, H.; Ghazoul, J.; Pacheco, P.; Rahmadian, F. Dynamics of Rural Economy: A Socio-Economic Understanding of Oil Palm Expansion and Landscape Changes in East Kalimantan, Indonesia. Land 2020, 9, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SPOTT. Palm Oil: ESG Policy Transparency Assessments. Sustainability Policy Transparency Toolkit. 2020. Available online: https://www.spott.org/palm-oil/ (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- Innocenti, E.D.; Oosterveer, P. Opportunities and bottlenecks for upstream learning within RSPO certified palm oil value chains: A comparative analysis between Indonesia and Thailand. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 78, 426–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilmar. Child Protection Policy; Wilmar International: Singapore, 2018; Available online: https://www.wilmar-international.com/docs/default-source/default-document-library/sustainability/policies/child-protection-policy.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- PRI. Fifty-Six Investors Sign Statement on Sustainable Palm Oil; Principles for Responsible Investment: London, UK, 2019; Available online: https://www.unpri.org/news-and-press/fifty-six-investors-sign-statement-on-sustainable-palm-oil/4266.article (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- Marti, S. Losing Ground: The Human Rights Impacts of Oil Palm Plantation Expansion in Indonesia; Friends of the Earth, Life Mosaic and Sawit Watch: London, UK, 2008; Available online: https://www.foei.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/losingground.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- Corciolani, M.; Gistri, G.; Pace, S. Legitimacy struggles in palm oil controversies: An institutional perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 212, 1117–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, S.; Khong, K.; Ha, N. Palm oil and its environmental impacts: A big data analytics study. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 274, 122901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketsela Moulat, B.; Brand-Weiner, I.; Elezaj, E.; Luzi, L. Commercial Pressures on Land and Their Impact on Child Rights: A Review of the Literature; Working Paper 2012-13; UNICEF Office of Research: Florence, Italy, 2012; Available online: https://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/pdf/iwp_2012_13.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- OHCHR. Joint Statement by the UN Special Rapporteurs on the Right to Food, Right to Health, the Working Group on Discrimination against Women in Law and in Practice, and the Committee on the Rights of the Child in Support of Increased Efforts to Promote, Support and Protect Breast-Feeding. United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. 2016. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=20871&LangID=E (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- Smit, L.; Holly, G.; McCorquodale, R.; Neely, S. Human rights due diligence in global supply chains: Evidence of corporate practices to inform a legal standard. Int. J. Hum. Rights 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grugel, J. Children’s rights and children’s welfare after the Convention on the Rights of the Child. Prog. Dev. Stud. 2013, 13, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PKPA. Toolkit 2018: Prinsip-Prinsip Bisnis Dan Hak Anak Di Sektor Perkebunan Kelapa Sawit; Pusat Kajian Perlindungan Anak: Medan, Indonesia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Vanclay, F.; Baines, J.; Taylor, C.N. Principles for ethical research involving humans: Ethical professional practice in impact assessment Part I. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2013, 31, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann-Pauly, D.; Posner, M. Making the business case for human rights: An assessment. In Business and Human Rights: From Principles to Practice; Baumann-Pauly, D., Nolan, D., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 11–21. [Google Scholar]

- Esteves, M.; Franks, D.; Vanclay, F. Social impact assessment: The state of the art. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2012, 30, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, G.; Scheyvens, R.; McLennan, S.; Bebbington, A. Conceptualising corporate community development. Third World Q. 2016, 37, 245–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wannags, L.; Gold, S. Assessing tensions in corporate sustainability transition: From a review of the literature towards an actor-oriented management approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 264, 121662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, T.; Figge, F.; Preus, L.; Pinkse, J. Trade-offs in corporate sustainability: You can’t have your cake and eat it. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2010, 19, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haffar, M.; Searcy, C. Classifications of trade-offs encountered in the practice of corporate sustainability. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 140, 495–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, T.; Pinkse, J.; Preuss, L.; Figge, F. Tensions in corporate sustainability: Towards an integrative framework. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 127, 297–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matinheikki, J.; Rajala, R.; Peltokorpi, A. From the profit of one toward benefitting many: Crafting a vision of shared value creation. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 162, S83–S93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adonteng-Kissi, O. Parental perceptions of child labour and human rights: A comparative study of rural and urban Ghana. Child Abus. Negl. 2018, 84, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ILO. Child Labour in Agriculture; International Labour Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://ilo.org/ipec/areas/Agriculture/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- Abebe, T.; Bessell, S. Dominant discourses, debates and silences on child labour in Africa and Asia. Third World Q. 2011, 32, 765–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suryahadi, A.; Priyambada, A.; Sumarto, S. Poverty, school and work: Children during the economic crisis in Indonesia. Dev. Chang. 2005, 36, 351–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolieb, J. Protecting the most vulnerable: Embedding children’s rights in the business and human rights project. In Research Handbook on Human Rights and Business; Deva, S., Birchall, D., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2020; pp. 354–378. [Google Scholar]

- Stamford Agreement. The Human Rights Based Approach to Development Cooperation towards a Common Understanding among UN Agencies. 2003. Available online: https://unsdg.un.org/download/85/279 (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- Elmhirst, R.; Sijapati Basnett, B.; Siscawati, M.; Ekowati, D. Gender Issues in Large Scale Land Acquisition: Insights from Oil Palm in Indonesia; Rights and Resources Initiative (RRI): Washington, DC, USA, 2017; Available online: https://rightsandresources.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Gender-Issues-in-Large-Scale-Land-Acquisition-Insights-from-Oil-Palm-in-Indonesia_April-2017_CIFOR.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- De Vos, R.; Delabre, I. Spaces for participation and resistance: Gendered experiences of oil palm plantation development. Geoforum 2018, 96, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center for Child Rights and Corporate Social Responsibility. In Family-Friendly Policies Handbook for Business; United Nations Children’s Fund East Asia and Pacific Regional Office: Bangkok, Thailand, 2020; Available online: https://www.unicef.org/eap/media/5901/file/Family-Friendly%20Policies:%20Handbook%20for%20Business.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2021).

| Objective | Examples of Good Practice |

|---|---|

| Increase awareness of children’s rights | Promulgate information to increase awareness of children’s rights and the company’s Code of Conduct, and have this information readily available in workplaces, plantation areas, and local villages. |

| Demonstrate commitment to children’s rights | Have policies, procedures, and a Code of Conduct that promote respect for children’s rights. Have a policy that specifically addresses children’s rights issues. Embed children’s rights thinking into all activities. |

| Ensure compliance with company policies and procedures relating to children’s rights | Have an effective monitoring and evaluation system to ensure that company staff, workers, and supply chain partners conform to the company’s requirements. |

| Ensure avoidance of child labour in company activities | Have knowledge of local labour law and child protection. Have a policy banning child labour. Have a system of monitoring potential child labour. Apply penalties for breaches of policies that relate to the rights of children. Consider what the company can do to address the root causes of child labour. |

| Eliminate child labour in all business relationships | Implement a prohibition of child labour in all contracting arrangements. Incentivise positive behaviour in contracting arrangements. Monitor contractors to ensure compliance with expectations. |

| Avoid undue separation of parents from their children due to working conditions | Ensure that working hours do not exceed what is reasonable. Ensure that pay rates provide a living wage so that parents do not feel compelled to work excessive hours. |

| Ensure working conditions do not limit staff and workers’ ability to play a proper role as parent | Provide decent and safe working conditions according to law, including facilities that support staff and workers in their role as parents, such as decent housing facilities, clean water, breastfeeding corners, health clinics. Allow workers to take paid leave for situations when the child requires special attention. |

| Avoid workers bringing their spouse and/or children to work on the plantations | Create awareness of the dangers of the workplace. Create awareness of the right of children to a childhood. Build schools near villages to reduce any barriers to access schooling. Provide child-care facilities and after-school activities. |

| Actively discourage informal understandings between workers and company staff that workers can bring their children to work | Put up signboards that state “Do not bring your children into these areas”. Penalise supervisors found guilty of allowing such practices. |

| Encourage children and youth to stay in school and avoid opportunities that encourage them to drop out of school | Ensure that schools are close to villages and/or provide a school bus service. Provide financial support for children and youth to remain at school. |

| Prevent environmental impacts (e.g., air or water pollution, plantation runoff or effluent) that may impair children’s health or development | Develop procedures to ensure that operational activities do not create adverse environmental or social impacts. Implement an effective environmental and social monitoring program. |

| Address all health and safety issues on the plantation that have the potential to affect children | Identify all potential adverse impacts of plantation activities on children’s health and develop company plans to mitigate them. Develop procedures that ensure the safety of children in all operational activities and facilities of the plantation. |

| Provide onsite healthcare for workers and community members | Build quality health clinics that are easily accessible by the community. |

| Take actions to avoid road accidents | Improve the condition of roads on which children travel. Erect warning signs on roads that are often travelled by children, such as the road to school, to playgrounds, or to their villages. Provide road-worthy school buses that can safely bring children to and from school. Limit the speed of company vehicles in local communities. Ensure that all vehicle drivers are trained and respect road rules. |

| Avoid physical displacement of families and any consequent disruption to children’s lives | Consider plantation siting carefully to minimise any displacement of households. Where physical displacement and resettlement are necessary, provide replacement land in a location that does not deprive children of their primary rights, such as right to education, to health, to play. Ensure that any resettlement is done to international standards, including adequate compensation, and that takes due regard to the needs of children. |

| Avoid economic displacement (disruption of livelihoods) | Conduct a Social Impact Assessment before any land acquisition process. In all land acquisition, consider how the livelihoods of local people will be affected. Ensure that there is compensation for economic displacement and the establishment of alternative livelihood arrangements. Allow local communities to use plantations areas for various livelihood activities (e.g., herding cattle, cutting grass for stock feed). |

| Avoid the loss of land as inheritance | In all resettlement, always ensure “land for land”. Ensure that land titles are given to households that are resettled. |

| In land acquisition, ensure no loss of access to education | Build a school near the community. |

| In land acquisition, avoid loss of access to children’s playgrounds | Provide safe playgrounds for children. Provide childcare centres that have competent staff. |

| Avoid resettlement arrangements that result in limited access to basic services | Provide adequate access to basic services and facilities for all workers and staff. |

| Prevent water shortages and/or increased distance between housing and water sources | Ensure that clean water is provided in all villages. |

| Prevent excessive pressure on social infrastructure that results in restricted access to basic services | Work together with local government to provide sufficient basic services. |

| Provide paid maternity leave | Provide paid maternity leave. |

| Provide special protection for pregnant and nursing women | Move pregnant and nursing women to safer work locations, e.g., away from chemicals. |

| Address issues related to long distances between housing and workplace | Provide adequate places where nursing mothers can breastfeed infants safely. |

| Ensure that the company’s products and services are safe | Undertake product testing before release of products. Monitor consumer complaints. |

| Only use marketing and advertising that respect and support children’s rights | Use reputable advertising companies. Use advertising and marketing that deliver positive messages and values regarding children. |

| Ensure respect for children’s rights in security arrangements | Develop a high standard of safety and security protocols for children who trespass on plantation sites. |

| Ensure children are protected during emergencies and conflict situations | Provide data for the local communities regarding natural disasters, epidemics, and social conflicts that can adversely affect children. Develop a disaster response policy specifically for children. Ensure there are well-considered contingency plans for effective disaster response that take a children’s rights perspective. |

| Reinforce community and government efforts to protect and fulfil children’s rights | Provide financial support to community programs. |

| Ensure that social investment considers children’s rights issues | Developing cooperation with organisations that concern and have expertise with children’s rights. |

| Ensure the protection of children in all business activities and business relationships | Implement clauses about respect for children’s rights in contracting arrangements. Incentivise business chain partners to respect children’s rights. |

| Respect the privacy of children | Recognize that children have the same right to privacy as adults, and that their informed consent is required before any disclosure or sharing of their data, information or images. |

| Provide compensation for any harm inflicted on families or communities | To ensure households are not economically disadvantaged (and thus causing hardship on children), attempt to prevent all harm befalling local people and communities, and where such harm happens, provide adequate compensation. |

| Provide appropriate avenues for children to indicate their grievances | Ensure that there are child-friendly mechanisms by which children can register any concerns they may have. |

| Ensure that sufficient resources are available | Ensure that sufficient resources are available to support all children’s rights programs and actions. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pasaribu, S.I.; Vanclay, F. Children’s Rights in the Indonesian Oil Palm Industry: Improving Company Respect for the Rights of the Child. Land 2021, 10, 500. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10050500

Pasaribu SI, Vanclay F. Children’s Rights in the Indonesian Oil Palm Industry: Improving Company Respect for the Rights of the Child. Land. 2021; 10(5):500. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10050500

Chicago/Turabian StylePasaribu, Stephany Iriana, and Frank Vanclay. 2021. "Children’s Rights in the Indonesian Oil Palm Industry: Improving Company Respect for the Rights of the Child" Land 10, no. 5: 500. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10050500

APA StylePasaribu, S. I., & Vanclay, F. (2021). Children’s Rights in the Indonesian Oil Palm Industry: Improving Company Respect for the Rights of the Child. Land, 10(5), 500. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10050500