Tourism Development Options in Marginal and Less-Favored Regions: A Case Study of Slovakia´s Gemer Region

Abstract

:1. Introduction

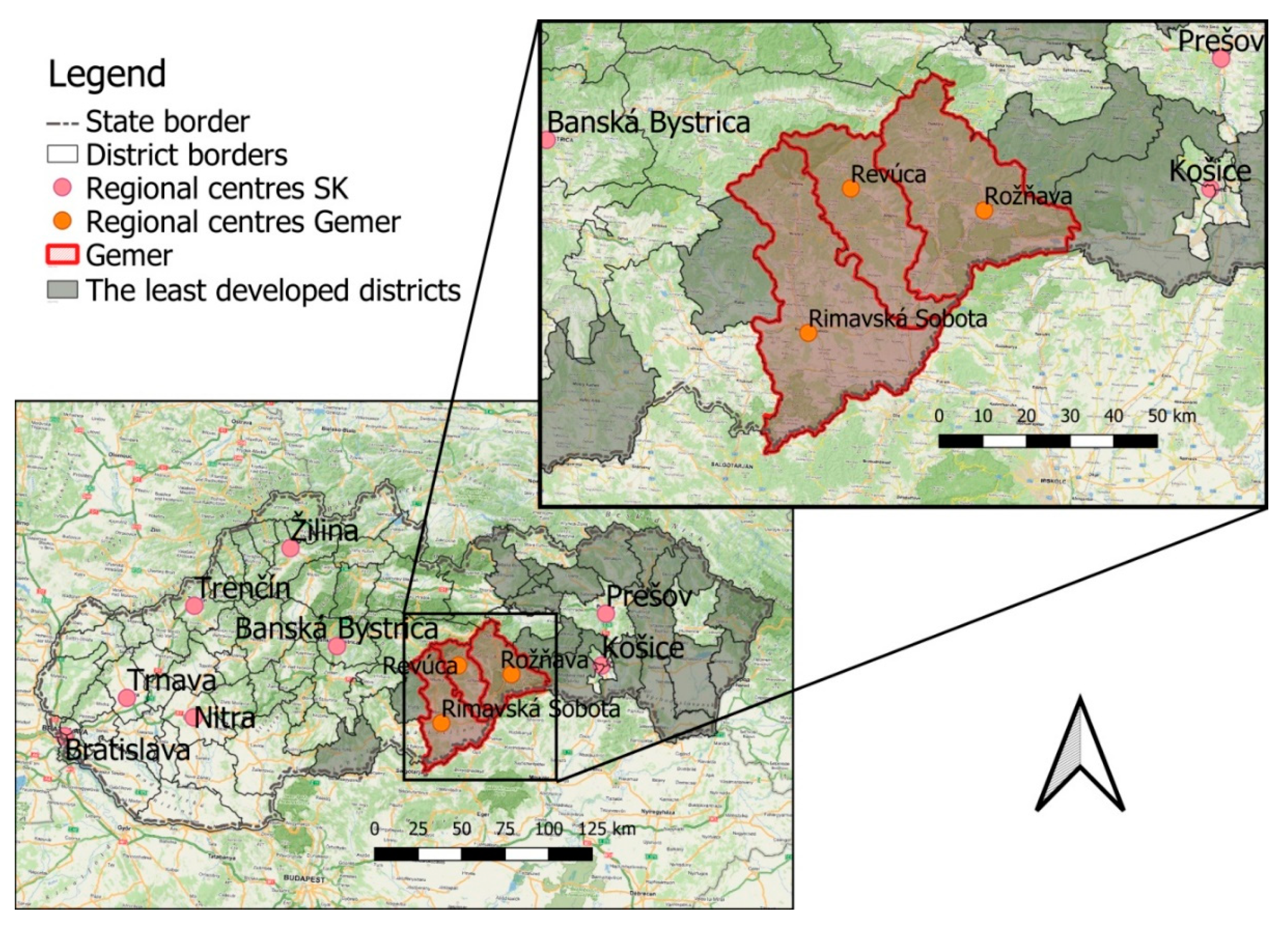

Study Area

2. Theory and Methods

- The natural and cultural attractions, as opportunities for tourism, were analyzed based on available data and literature review.

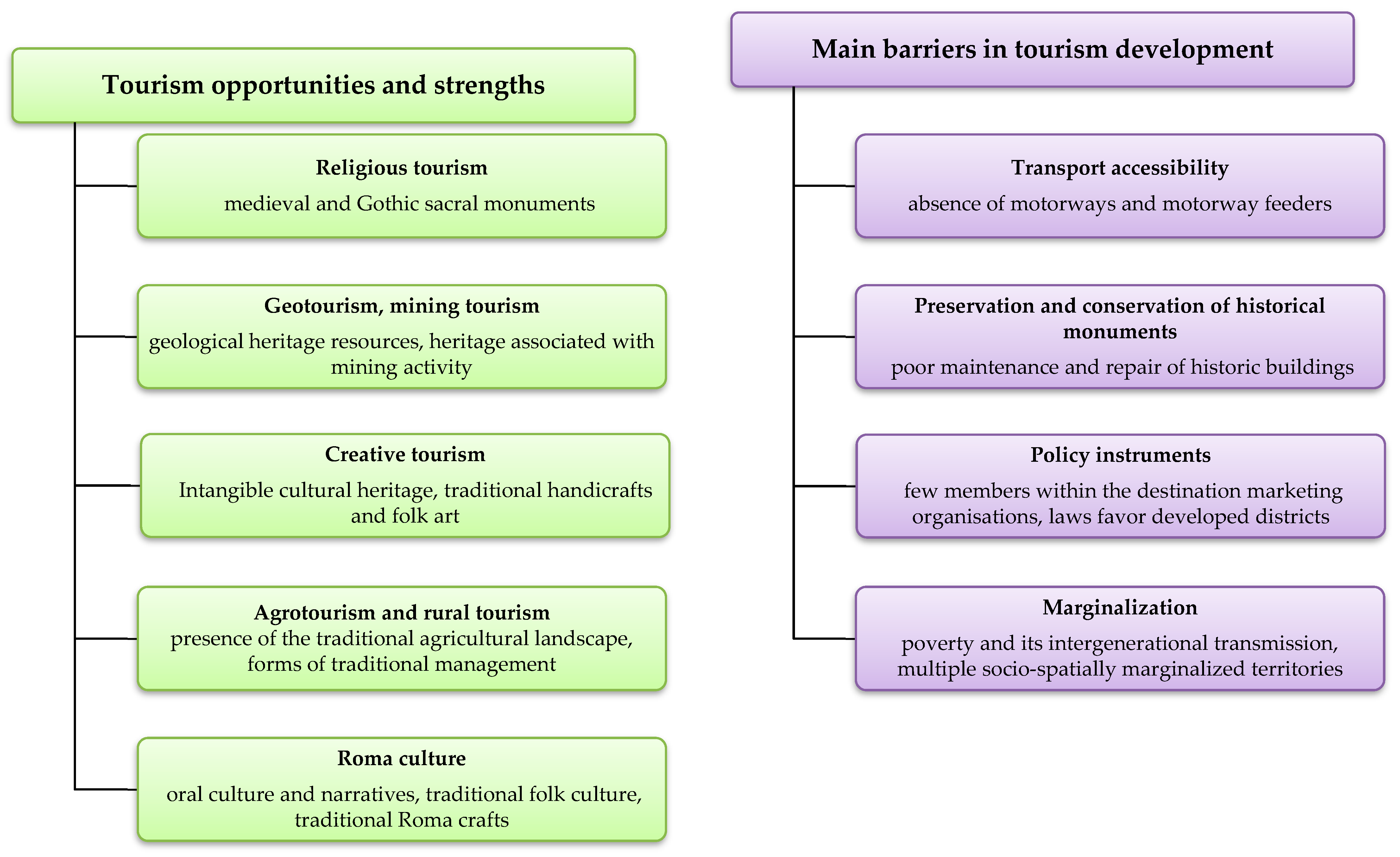

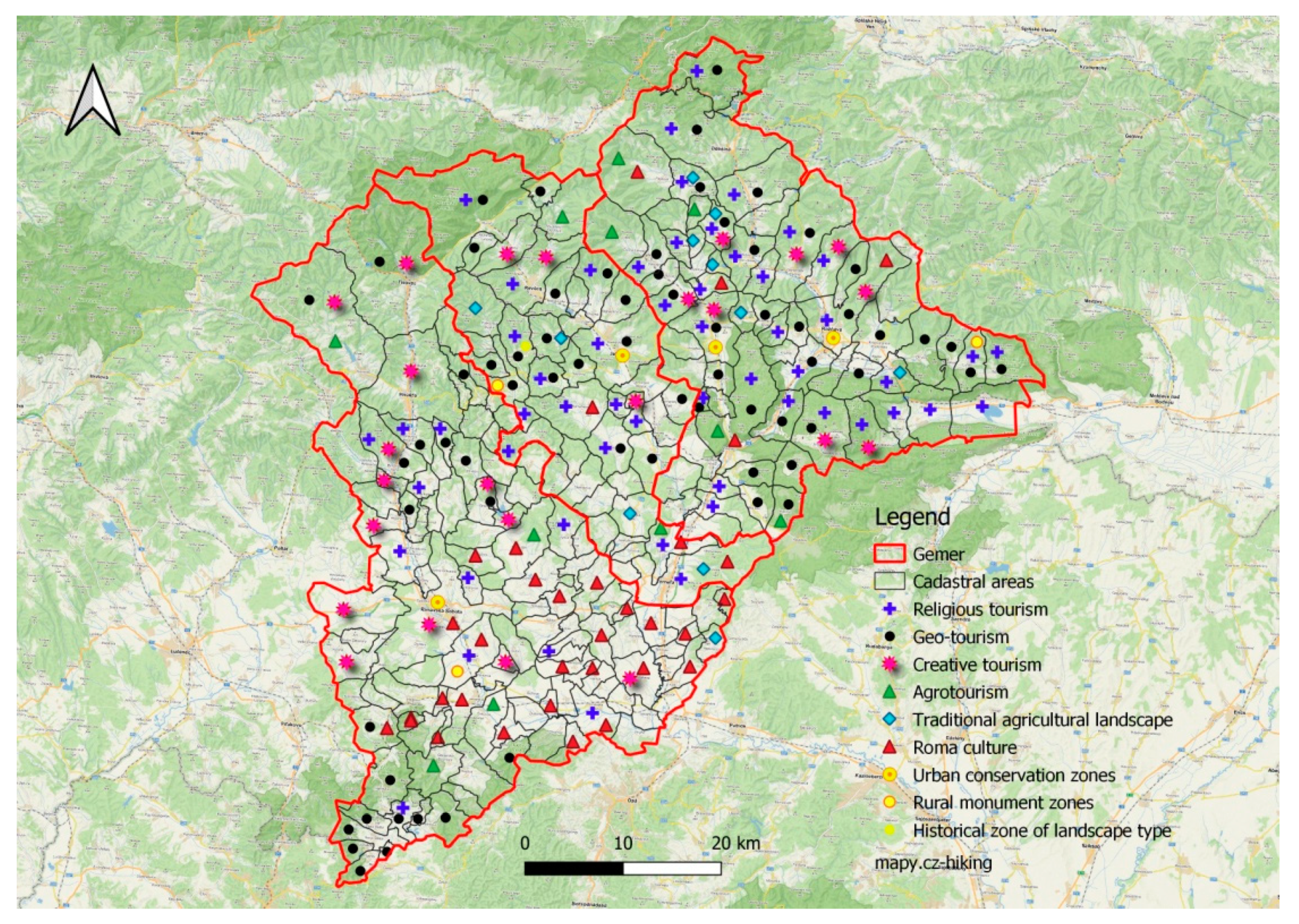

- The most promising types, in terms of potential and opportunities for tourism, are described with reference to the natural and cultural attractions (Figure 2).

- For each type of tourism, key characteristics were selected and available data were analyzed and used for assessment.

- Religious tourism—Europe is characterized by a rich net of itineraries that were followed during the Middle Ages by pilgrims heading toward the holy places of Christianity. The aim of “religious tourism” is to visit sacred sites associated with a particular cult or religion, forms of spirituality, or special revelations [39]. The motivations and behaviors include not only religious factors but are also related to cultural heritage tourism, recreation, social/family life, new experiences, etc. [40]. Religious tourism represents an essential element for guaranteeing socio-economic sustainability to the hosting communities and is a precondition for the promotion of intercultural dialogue [41]. Pilgrimage tourism is considered part of religious tourism, which United Nations World Tourism Organization ranks as fifth-place among motivations to travel [42]. In our study, it was assessed on the basis of the presence of religious and sacred cultural monuments on the Gothic route.

- Geotourism and mining tourism—based on the region’s mining history. Numerous monuments survive, which testify to the mining history of the area, and geological heritage resources offer options for the development of this type of tourism. Geodiversity is the natural range of geological rocks, minerals, fossils, geomorphological forms and processes, and soil features. It includes their assemblages, relationships, properties, and systems [43]. Geotourism is a multi-interest kind of tourism, exploiting natural sites and landscapes containing interesting earth-science features in a didactic and entertaining way [44,45]. Integrating the preservation of geological heritage into a strategy for regional sustainable economic and cultural development is the general goal of geoparks [46,47]. A “geopark” is an area containing a number of protected geosites, which are included in an integrated concept of protection, education, and sustainable development [38]. Mining heritage, in Slovak terminology, falls under the category "technical monuments"; but the term “mining heritage” incorporates natural, historical, architectural, technological, technical, artistic, documentary, geomorphologic, and other aspects. Another relevant term is “mining heritage related to cultural heritage,” which additionally incorporates archaeological, industrial, and other attributes. It can also cover territories that have long depended on mining [25].

- Creative tourism—This offers an opportunity for learning and experiencing an intangible cultural heritage, traditional handicrafts, and folk art. Creativity relies on human capital and is viewed as a sustainable and renewable resource, which does not need a great number of funds for preservation and maintenance [48]. It can be used as an instrument to produce more meaningful and also stronger links between the environmental, social, and economic goals of sustainable development. It combines cultural interest with great natural beauty to develop places more suitable for vacation, permanent residency, employment, and investments [49]. Creativity and creative tourism are based on intangible and contemporary creativity and can be used as a way to stabilize communities and solve community problems [50,51]. Today, creative tourism consists of a bundle of dynamic creative relationships between people, places, and ideas, through which lives can be improved and injected with new potential [52]. In our study, it represents municipalities in which, according to the Centre for Folk Art Production, craftsmen keep their crafts alive.

- Agrotourism—The presence of traditional agricultural land (TAL), which was evaluated by our own field research [53] on the basis of field mapping of TAL and aerial photos using a 1 km2 network created in Google Earth, is also of great importance for sustainable tourism. TAL mainly constitutes extensively farmed fields, meadows, pastures, orchards, and vineyards, much of which has been abandoned or contains currently unused areas of low succession, and which was not affected by the intensification of agriculture during socialism. However, this type of landscape has been steadily disappearing since 1989, due to processes of abandonment of agricultural land [54]. The diversification of local farms can bring new job opportunities to rural regions on the basis of environmentally friendly agriculture, production, and tourism [55]. Our study focused on the selection of villages with the presence of TAL and with a real potential for agricultural renewal and rural tourism.

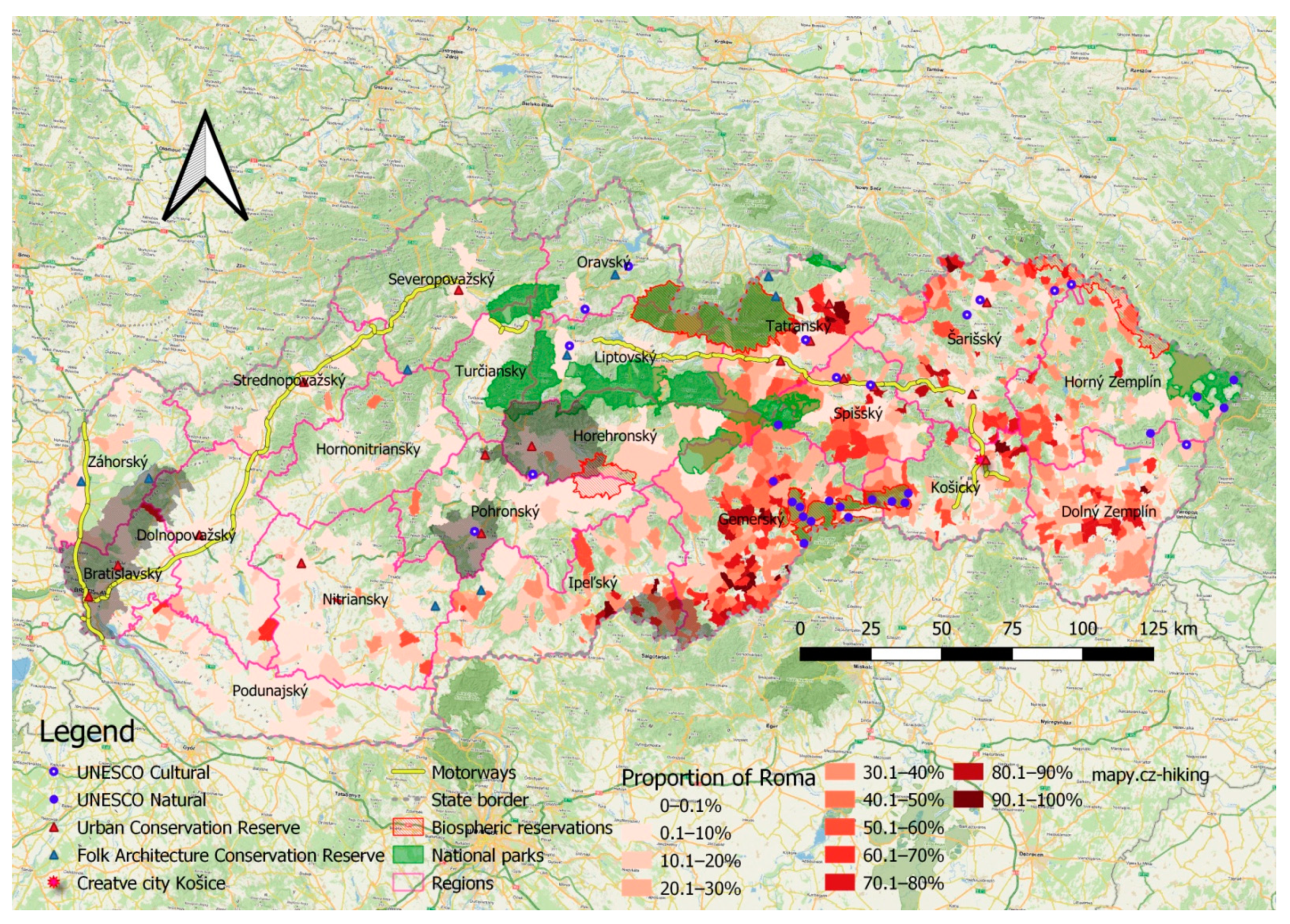

- Roma culture—The population dynamics of the Roma, and their activity in the labor market, level of education, dependence on social assistance, health status, and crime levels have been addressed by a number of publications, but only a few literature analyses are devoted to their history and culture and the discrimination and marginalization they face in Slovakia [5,6,7,8,24,27,29,56,57,58,59,60,61]. The study of the heritage of Roma culture offers a great wealth of resources for tourism development, e.g., traditional Roma music and crafts. At present, opportunities for tourism development are provided by municipalities that seek to preserve Roma culture on the basis of an application for financial support from the Fund for the Support of the Culture of National Minorities.

- In addition to tourism development options, we defined and discussed the main barriers to tourism development.

3. Results

3.1. Tourism Opportunities and Strengths

3.1.1. Religious Tourism

3.1.2. Geotourism and Mining Tourism

3.1.3. Creative Tourism

3.1.4. Agrotourism Associated with the Traditional Agricultural Landscape

3.1.5. Heritage of Roma Culture

3.2. Main Barriers in Tourism Development

3.2.1. Transport Accessibility

3.2.2. Insufficient Preservation and Conservation of Historical Monuments

3.2.3. Policy Instruments on the Promotion of Tourism

3.2.4. Territories with Multiplied Socio–Spatial Marginalization

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gajdoš, P. Marginal regions in Slovakia and their developmental disposabilities. Agric. Econ. 2005, 51, 555–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzambazovic, R. Spatial aspects of poverty and social exclusion. Sociologia 2007, 39, 432–458. [Google Scholar]

- Gajdoš, P.; Pašiak, J. Regional Development of Slovakia: From the Perspective of Spatial Sociology (In Slovak: Regionálny Rozvoj Slovenska: Z Pohľadu Priestorovej Sociológie); Sociologický Ústav SAV: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2006; ISBN 80-85544-46-6. [Google Scholar]

- Matlovič, R.; Matlovičová, K. Regional disparities and their solution in Slovakia in the various contexts. Folia Geogr. 2011, LIII, 8–87. [Google Scholar]

- Rusnáková, J.; Rochovská, A. Segregation of the Marginalized Roma Communities Population, Poverty and Disadvantage Related to Spatial Exclusion. Geogr. Cassoviensis 2014, VIII, 162–172. [Google Scholar]

- Šuvada, M.; Slavík, V. Contribution of Slovak geography into to research of Roma minority in Slovak republic (In Slovak: Prínos Slovenskej geografie do výskumu Rómskej minority v Slovenskej republike). Acta Geogr. Univ. Comen. 2016, 60, 207–236. [Google Scholar]

- Facuna, J.; Lužica, R. Roma Culture (In Slovak: Rómska Kultúra); Štátny pedagogický ústav: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2017; p. 105. ISBN 978-80-8118-188-7. [Google Scholar]

- Šuvada, M. Roma in Slovak Cities (In Slovak: Rómovia v Slovenských Mestách); POMS: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2015; p. 168. ISBN 978-80-8061-828-5. [Google Scholar]

- Šprocha, B. Reproduction of Roma Inhabitants in Slovakia and Prognosis of Their Population Development (In Slovak: Reprodukcia Rómskeho Obyvatel’stva na Slovensku a Prognóza jeho Populačného Vývoja); Prognostický ústav Slovenskej akadémie vied: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2014; ISBN 978-80-89037-38-4. [Google Scholar]

- Saxena, G.; Ilbery, B. Integrated rural tourism—A border case study. Ann. Tour. Res. 2008, 35, 233–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R.W. Sustainable tourism: A state-of-the-art review. Tour. Geogr. 1999, 1, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Clark, G.; Chabrel, M. Measuring Integrated Rural Tourism. Tour. Geogr. 2007, 9, 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yu, L.; Wang, G.; Marcouiller, D.W. A scientometric review of pro-poor tourism research: Visualization and analysis. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 30, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielinski, S.; Jeong, Y.; Kim, S.; Milanés Batista, C. Why Community-Based Tourism and Rural Tourism in Developing and Developed Nations are Treated Differently? A Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matlovičová, K.; Kolesárová, J.; Matlovič, R. Selected theoretical aspects of the destination marketing based on participation of marginalized communities. In Proceedings of the Zborník Recenzovaných Príspevkov z 8. Ročníku Mezinárodní Vědecké Konference, Praha, Czech Republic, 8–9 March 2016; pp. 128–143, ISBN 978-80-87411-75-9. [Google Scholar]

- Matlovičová, K. Place Branding (In Slovak: Značka územia); Fakulta humanitných a prírodných vied: Prešov, Slovakia, 2015; p. 320. ISBN 978-80-555-1529. [Google Scholar]

- Matlovič, R.; Matlovičová, K.; Kolesárová, J. Conceptualization of the historic mining towns in Slovakia in the institutional, urban-physiological and urban-morphological context. In Enhancing Competitiveness of V4 Historic Cities to Develop Tourism: Spatial-Economic Cohesion and Competitivness in the Context of Tourism; Radics, Z., Penczes, J., Eds.; Didakt Kft: Debrecen, Debrecen, 2014; pp. 165–193. ISBN 978-615-5212-22-2. [Google Scholar]

- Miklós, L. Natural—Settlement nodal regions 1: 500 000. In Atlas of Landscape of Slovak Republic (In Slovak: Atlas krajiny Slovenskej republiky); Ministerstvo Životného Prostredia SR a Banská Bystrica, Slovenská Agentúra Životného Prostredia: Bratislava, Banská Bystrica, Slovakia, 2002; pp. 206–207. ISBN 80-88833-27-2. [Google Scholar]

- Mazúr, E.; Lukniš, M. Geomorphological units 1: 1 000 000. In Atlas of Landscape of Slovak Republic (In Slovak: Atlas Krajiny Slovenskej Republiky); Ministerstvo Životného Prostredia SR a Banská Bystrica, Slovenská Agentúra Životného Prostredia: Bratislava, Banská Bystrica, Slovakia, 2002; p. 88. ISBN 80-88833-27-2. [Google Scholar]

- Mazúr, E.; Činčura, J.; Kvitkovič, J. Geomorphological situation. In Atlas of Landscape of Slovak Republic (In Slovak: Atlas Krajiny Slovenskej Republiky); Ministerstvo Životného Prostredia SR a Banská Bystrica, Slovenská Agentúra Životného Prostredia: Bratislava, Banská Bystrica, Slovakia, 2002; pp. 86–87. ISBN 80-88833-27-2. [Google Scholar]

- Slovak Hydrometeorological Institute. Climatological Atlas of Slovakia (In Slovak: Klimatický atlas Slovenska); Slovenský Hydrometeorologický Ústav: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rybár, P.; Molokáč, M.; Hvizdák, L.; Štrba, Ľ.; Böhm, J. Territory of Eastern Slovakia—Area of mining heritage of mediaeval mining. Acta Geoturistica 2012, 3, 29–35. [Google Scholar]

- Štefánik, M.; Lukačka, J. Lexicon of Medieval Towns in Slovakia; Slovenská Akadémia Vied (Bratislava), a Historický Ústav, Bratislava, Historický Ústav SAV: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Jurová, A. Historical development of Roma settlements in Slovakia and the issue of ownership of land (“illegal settlements”). Individ. Soc. 2002, 5, 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Rybár, P.; Molokáč, M.; Hvizdák, L.; Štrba, Ľ.; Böhm, J. Upper Hungarian Mining Route. Geoconference Ecol. Econ. Educ. Legis. 2014, I, 793–798. [Google Scholar]

- Matlovičová, K.; Matlovič, R.; Mušinka, A.; Židová, A. The Roma population in Slovakia. Basic characteristics of the Roma population with emphasis on the spatial aspects of its differentiation. In Roma Population on The Peripheries of the Visegrad Countries: Spatial Trends and Social Challenges; Penczes, J., Radics, Z., Eds.; Didakt: Debrecen, Hungary, 2012; pp. 77–104. ISBN 978-615-5212-07-9. [Google Scholar]

- Crowe, D. A History of the Gypsies of Eastern Europe and Russia; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Tkáčová, A. The life of the Roma in the archive material from the 18th and 19th centuries. Individ. Soc. 2005, 8, 31–35. [Google Scholar]

- Podolák, P. Geographic and demographic characteristics of Gypsy population in Slovakia. Geogr. Časopis 2000, 52, 269–284. [Google Scholar]

- Dunko, T. Roma Cultural Identity and Central Europe In Slovak: Rómska Kultúrna Identita a Stredná Európa. Ph.D. Thesis, Masarykova Univerzita Filozofická Fakulta Ústav Slavistiky, Brno, Czechia, 2019; p. 206. [Google Scholar]

- Jurova, A. Social-Problems of Roms (gypsies) Today and in the Past—Czech—Necas,c. Hist. Cas. 1992, 40, 403. [Google Scholar]

- Musterd, S. Social and ethnic segregation in Europe: Levels, causes, and effects. J. Urban Aff. 2005, 27, 331–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musterd, S.; Ostendorf, W. Social Exclusion, Segregation, and Neighborhood Effects; Blackwell Science Publ: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Brama, A. ‘White flight’? The production and reproduction of immigrant concentration areas in Swedish cities, 1990–2000. Urban Stud. 2006, 43, 1127–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Interior of Slovak Republic–Roma Communities (In Slovak: Ministerstvo Vnútra SR—Rómske Komunity). Available online: https://www.minv.sk/?atlas-romskych-komunit-2019 (accessed on 19 July 2020).

- Demo, M.; Bielek, P.; Čanigová, M.; Duďák, J.; Fehér, A.; Hraška, Š.; Hričovský, I.; Hubinský, J.; Ižáková, V.; Látečka, M. History of Agriculture in Slovakia; Slovak University of Agriculture: Nitra, Slovakia, 2001; 662p. [Google Scholar]

- Aláč, J. Onechildhood. Stories about Deserted Schools and Empty Yards (In Slovak: Jednodetstvo. Rozprávanie o Pustých Školácha a Prázdnych Dvoroch). In Secret Killers (In Slovak: Tajní Vrahovia), 2nd ed.; Miloš Hric, 2017; ISBN 9788097211219. Available online: https://www.tyzden.sk/klub/45126/tajni-vrahovia/ (accessed on 24 February 2021).

- Michálek, A. Poverty at the local level (Poverty centres in Slovakia). Geogr. J. 2004, 56, 225–247. [Google Scholar]

- Svoboda, J.; Šalgovičová, J.; Polakovič, A. Religion and Tourism in Slovakia. Eur. J. Sci. 2013, 9, 125–132. [Google Scholar]

- Liro, J. Visitors’ motivations and behaviours at pilgrimage centres: Push and pull perspectives. J. Herit. Tour. 2020, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabio, C.; Gian, C.; Anahita, M. New Trends of Pilgrimage: Religion and Tourism, Authenticity and Innovation, Development and Intercultural Dialogue: Notes from the Diary of a Pilgrim of Santiago. Aims Geosci. 2016, 2, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Tourism Organisation (UNTWO) (Ed. ) Walking Tourism—Promoting Regional development, Executive Summary; World Tourism Organisation (UNTWO): Madrid, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, M. Geodiversity: Valuing and Conserving Abiotic Nature; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Pralong, J.-P. Geotourism: A new Form of Tourism utilising natural Landscapes and based on Imagination and Emotion. Tour. Rev. 2006, 61, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farsani, N.T.; Coelho, C.; Costa, C. Geotourism and Geoparks as Novel Strategies for Socio-economic Development in Rural Areas. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2011, 13, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eder, W. Geoparks—Promotion of Earth Sciences through Geoheritage Conservation, Education and Tourism. J. Geol. Soc. India 2008, 72, 149–154. [Google Scholar]

- Telbisz, T.; Bottlik, Z.; Mari, L.; Petrvalská, A. Exploring Relationships between Karst Terrains and Social Features by the Example of Gömör-Torna Karst (Hungary-Slovakia). Acta Carsologica 2015, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Richards, G.; Wilson, J. Developing creativity in tourist experiences: A solution to the serial reproduction of culture? Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 1209–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitsani, E.; Kavoura, A. Host Perceptions of Rural Tour Marketing to Sustainable Tourism in Central Eastern Europe. The Case Study of Istria, Croatia. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 148, 362–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. Tourism and the Creative Economy|en|OECD. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/publications/tourism-and-the-creative-economy-9789264207875-en.htm (accessed on 9 February 2021).

- Fernandes, C. Cultural planning and creative tourism in an emerging tourist destination. Int. J. Manag. Cases 2011, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, G. Designing creative places: The role of creative tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 85, 102922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrovodská, M.; Špulerová, J.; Štefunková, D.; Halabuk, A. Research and Maintenance of Biodiversity in Historical Structures in the Agricultural Landscape of Slovakia. In Landscape Ecology—Methods, Applications and Interdisciplinary Approach; Barančoková, M., Krajčí, J., Kollár, J., Belčáková, I., Eds.; Institute of Landscape Ecology, Slovak Academy of Sciences: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2010; pp. 131–140. ISBN 978-80-89325-16-0. [Google Scholar]

- Špulerová, J.; Bezák, P.; Dobrovodská, M.; Lieskovský, J.; Štefunková, D. Traditional agricultural landscapes in Slovakia: Why should we preserve them? Landsc. Res. 2017, 42, 891–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krnáčová, Z.; Pavličková, K.; Spišiak, P. The assumptions for the tourism development in rural areas in Slovakia. Ekol. Bratisl. 2001, 20, 317–324. [Google Scholar]

- Brearley, M. The Persecution of Gypsies in Europe. Am. Behav. Sci. 2001, 45, 588–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jurová, A. Educational Handicap of Romany Population—The Ways of Its Overcoming and Future Possibilities. Sociologia 1994, 26, 479. [Google Scholar]

- Lášticová, B.; Popper, M. Identifying Evidence-Based Methods to Effectively Combat Discrimination of the Roma in the Changing Political Climate of Europe. Ústav Výskumu Sociálnej Komunikácie SAV. 2017. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/341726602_Narodna_sprava_WP3_Temy_zdroje_a_mozne_dosledky_politickeho_diskurzu_o_Romoch_na_Slovensku (accessed on 5 August 2020).

- Kozoň, A.; Malík, B.; Šebestová, P.; Hejdiš, M.; Mojžišová-Magdolenová, K.; Bombeková, T.; Havrillayová, A.; Kusín, V.; Drábiková, J.; Budayová, Z. Insight on Traditional Roma Culture in Process of Socialisation (In Slovak: Náhľad na Tradičnú Rómsku Kultúru v Procese Socializácie); Fakulta sociálnych štúdií Vysokej školy Danubius, Sládkovičovo Spoločnosť pre Sociálnu integráciu v SR, SpoSoIntE: Trenčín, Slovakia, 2016; p. 243. ISBN 978-80-89533-18-3. [Google Scholar]

- Mušinka, A.; Škobla, D.; Hurrle, J.; Matlovičová, K.; Kling, J. Atlas of Roma Communities in Slovakia 2013 (In Slovak: Atlas Rómskych Komunit na Slovensku 2013); Regionálne Centrum Rozvojového Programu OSN Pre Európu a Spoločenstvo Nezávislých štátov: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Marcinčin, A.; Marcinčinová, Ľ. The Cost of Non-Inclusion. The key to Integration is respect for diversity (In Slovak: Straty z Vylúčenia Rómov. Kľúčom k Integrácii je rešpektovanie inakosti). Diskriminácia 2011. Available online: http://diskriminacia.sk/straty-z-vylucenia-romov-klucom-k-integracii-je-respektovanie-inakosti/ (accessed on 25 June 2020).

- Zubrický, G.; Szöllös, J. Gemer (Malohont)—Tourist Guide (In Slovak: Gemer (Malohont)—Turistický Sprievodca), 1st ed.; DAJAMA: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Welcome to Slovak Gothic Route! Available online: http://www.gothicroute.sk/ (accessed on 6 February 2020).

- Kravec, J.; Hudáček, J. In the Footsteps of the History of Mining, Metallurgy and Ironworks in the Spiš-Gemer Ore Mountains (In Slovak: Po Stopách Histórie Baníctva, Hutníctva a Železiarstva v Spišsko-Gemerskom Rudohorí). Rožňava: Rudňany: Gemerský Banícky Spolok—Bratstvo; Banícky Cech. 2007. 31. Available online: http://sclib.svkk.sk/sck01/Record/000616693 (accessed on 24 February 2021).

- UNESCO. Unesco Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage Intergovernmental Committee for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage. In Proceedings of the Tenth Session, Windhoek, Namibia, 30 November–4 December 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Environment of the Slovak Republic. National Parks, NP Slovenský Kras (In Slovak: Národné Parky, NP Slovenský Kras). Available online: http://npslovenskykras.sopsr.sk/ (accessed on 4 February 2020).

- Ministry of Environment of the Slovak republic. National Parks, NP Muránska Planina (In Slovak: Národné Parky, NP Muránska Planina). Available online: http://npmuranskaplanina.sopsr.sk/ (accessed on 4 February 2020).

- Horvath, G.; Csuelloeg, G. A New Slovakian-Hungarian Cross-Border Geopark in Central Europe—Possibility for Promoting Better Connections Between the Two Countries. Eur. Ctry. 2013, 5, 146–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- The Monuments Board of the Slovak Republic—General List of Monuments in Slovakia. (In Slovak: Pamiatkový úrad Slovenskej Republiky—Evidencia Národných Kultúrnych Pamiatok na Slovensku). Available online: http://www.pamiatky.sk/ (accessed on 22 January 2021).

- European Theme Routes—ERIH. Available online: https://www.erih.net/ (accessed on 5 August 2020).

- The Centre for Folk Art Production. Manufacturers. Available online: http://www.uluv.sk/ (accessed on 6 August 2020).

- Elements Included in the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Slovakia—Slovak Intangible Cultural Heritage Centre (In Slovak: Prvky Zapísané v Reprezentatívnom Zozname NKD Slovenska—Centrum pre Tradičnú Ľudovú Kultúru). Available online: https://www.ludovakultura.sk/zoznamy-nkd-slovenska/reprezentativny-zoznam-nehmotneho-kulturneho-dedicstva-slovenska/prvky-zapisane-v-reprezentativnom-zozname-nkd-slovenska/ (accessed on 7 February 2020).

- Industrial Property Office of the Slovak republic. List of Registered and Protected Designations of Origin and Geographical Indicators in the Register of the Industrial Property Office of the Slovak Republic (In Slovak: Zoznam Zapísaných a Chránených Označení Pôvodu a Zemepisných Označení do Registra Úradu Priemyselného Vlastníctva Slovenskej Republiky). Available online: https://www.indprop.gov.sk/?zoznam-zapisanych-a-chranenych-oznaceni-povodu-a-zemepisnych-oznaceni-do-registra-uradu-priemyselneho-vlastnictva-slovenskej-republiky (accessed on 7 February 2020).

- ©NPPC-VÚPOP, Ortofoto: ©EUROSENSE s.r.o., ©GEODIS s.r.o., Parametre BPEJ. Available online: https://portal.vupop.sk/portal/apps/webappviewer/index.html?id=d89cff7c70424117ae01ddba7499d3ad (accessed on 6 February 2020).

- Ostrovský, R.; Brindza, J.; Stehlíková, B. Phenotypic variability of traits of sweet cherry (Cerasus avium L.) elementary organs of local and old varieties genepool in Brdárka cadaster. In Výsledky a Prínosy Excelentného Centra Ochrany a Využívania Agrobiodiverzity: Vedecké Práce Fakulty Agrobiológie a Potravinových Zdrojov SPU v Nitre; Bežo, M., Ondrišík, P., Eds.; SPU Nitra: Nitra, Slovakia, 2011; ISBN 978-80-552-0589. [Google Scholar]

- Thurzo, I. Dispersed Settlement—A Traditional Part of Our Countryside. Životné Prostr. 1997, 2, 67–72. [Google Scholar]

- Podoba, J. Out from the Village (Changes of the Settlements Outside the Village in Muránska Zdychava). Životné Prostr. 1997, 31, 90–93. [Google Scholar]

- Slovak Intangible Cultural Heritage Cnetra. Roma in Slovakia (In Slovak: Centrum pre Tradičnú Ľudovú Kultúru. Rómovia na Slovensku). Available online: https://www.ludovakultura.sk/polozka-encyklopedie/romovia-na-slovensku (accessed on 22 July 2020).

- Daneková, A. On the Activity of the Museum of Culture of the Roma in Slovakia (In Slovak: K činnosti Múzea kultúry Rómov na Slovensku). Zborník Slov. Národného Múzea V Mar. Etnogr. 2015, CIX 56, 99–116. [Google Scholar]

- Michniak, D. Selected approaches to transport accessibility assessment in relation to the development of tourism. Geogr. J. 2014, 66, 21–28. [Google Scholar]

- Gregorová, B. Tourism as an Instrument of Economic Development of the Banská Bystrica Self-Governing Region. Entrep. Educ. 2018, 14, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Transport and Construction of the Slovak Republic. Register of Regional Tourism Organizations (In Slovak: Register Oblastných Organizácií Cestovného Ruchu). Available online: https://www.mindop.sk/ministerstvo-1/cestovny-ruch-7/register-organizacii-cestovneho-ruchu/register-oblastnych-organizacii-cestovneho-ruchu (accessed on 30 January 2020).

- Slov-lex, 347/2018 Z.z. Available online: https://www.slov-lex.sk/pravne-predpisy/SK/ZZ/2018/347/ (accessed on 17 June 2020).

- Ministry of Transport and Construction of the Slovak Republic. List of Applicants for Subsidies within the Meaning of Act no. 91/2010 Coll. on Tourism Promotion as Amended (In Slovak: Zoznam Žiadateľov o Dotáciu v Zmysle Zákona č. 91/2010 Z. z. o Podpore Cestovného Ruchu v Znení Neskorších Predpisov). Available online: https://www.mindop.sk/ministerstvo-1/cestovny-ruch-7/poskytovanie-dotacii/zoznam-ziadatelov-o-dotaciu-v-zmysle-zakona-c-91-2010-z-z-o-podpore-cestovneho-ruchu-v-zneni-neskorsich-predpisov (accessed on 2 June 2020).

- Michálek, A. Concentration and attributes of poverty in Slovak Republic at the local level. Geogr. Časopis 2005, 57, 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Rusnáková, J.; Rochovská, A. Social exclusion, segregation and livelihood strategies of the Roma communities in terms of asset theory. Geogr. Časopis Geogr. J. 2016, 68, 245–260. [Google Scholar]

- Radičová, I. Roma on the Doorstep of Transformation. In Čačipen pal o Roma. Summary Report on the Roma in Slovakia (In Slovak Rómovia na Prahu Transformácie). In Vašečka, M., Eds. Čačipen pal o Roma. [General report on Roma in Slovakia]. Bratislava, IVO: 79–91. Available online: http://www.ivo.sk/495/sk/projekty/suhrnna-sprava-o-romoch-na-slovensku (accessed on 23 June 2020).

- Džambazovič, R. Spatial Aspects of Poverty and Social Exclusion (In Slovak: Priestorové aspekty chudoby a sociálneho vylúčenia). Sociológia 2007, 39, 432–458. [Google Scholar]

- Judák, V.; Poláčik, Š. Catalog of Patrociniums in Slovakia (In Slovak: Katalóg patrocínií na Slovensku), 1st ed.; Rímskokatolícka Cyrilometodská Bohoslovecká Fak. UK Bratislava: Bratislava, Slovak Republic, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Krogmann, A.; Solcova, L.; Nemcikova, M.; Mroz, F.; Ambrosio, V. Possibilities of St. James Routes Development in Slovakia. In v Geograficke Informacie; Dubcova, A., Ed.; Constantine Philosopher Univ Nitra: Nitra, Slovakia, 2016; Volume 20, pp. 231–238. [Google Scholar]

- Slivka, M.; Petranová, D. Faith Tourism in Slovakia; Nardini Editore: Fiesole, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Krempaská, Z.; Jančura, M.; Števík, M. Slovak mining route and European iron trail in Slovakia. In Proceedings of the CIMUSET 2013. International Committees Meeting. Controversy, Connections and Creativity (CD) Rio de Janeiro. 2013. Available online: http://site.mast.br/multimidias/cimuset_2013/pdf_zuzana_paper.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2020).

- Hronček, P.; Gregorová, B.; Tometzová, D.; Molokáč, M.; Hvizdák, L. Modeling of Vanished Historic Mining Landscape Features as a Part of Digital Cultural Heritage and Possibilities of Its Use in Mining Tourism (Case Study: Gelnica Town, Slovakia). Resources 2020, 9, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldighieri, B.; Testa, B.; Bertini, A. 3D Exploration of the San Lucano Valley: Virtual Geo-routes for Everyone Who Would Like to Understand the Landscape of the Dolomites. Geoheritage 2016, 1, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hronček, P.; Lukac, M. Anthropogenically Created Historical Geological Surface Locations (geosites) and Their Protection. In Public Recreation and Landscape Protection—With Nature Hand in Hand! Fialova, J., Ed.; Mendel Univ Brno: Brno, Czech Republic, 2019; pp. 54–60. [Google Scholar]

- Telbisz, T.; Gruber, P.; Mari, L.; Kőszegi, M.; Bottlik, Z.; Standovár, T. Geological Heritage, Geotourism and Local Development in Aggtelek National Park (NE Hungary). Geoheritage 2020, 12, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Štrba, Ľ.; Kolačkovská, J.; Kudelas, D.; Kršák, B.; Sidor, C. Geoheritage and Geotourism Contribution to Tourism Development in Protected Areas of Slovakia—Theoretical Considerations. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Czwartynska, M. The mining regions in the post-industrial transformation of Upper Silesia. Prace Komisji Geogr. Prezemys. Pol. Tow. Geogr. 2008, 10, 76–85. [Google Scholar]

- Duży, S.; Dyduch, G.; Preidl, W.; Stacha, G. Drainage Adits in Upper Silesia—Industrial Technology Heritage and Important Elements of the Hydrotechnical Infrastructure. Studia Geotech. Et Mech. 2017, 39, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lamparska, M. Post-industrial Cultural Heritage Sites in the Katowice conurbation, Poland. Environ. Socio-Econ. Stud. 2013, 1, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lamparska, M. “Post-mining tourism in Upper Silesia and Czech-Moravian country”. J. Geogr. Politics Soc. 2019, 9, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metsaots, K.; Printsmann, A.; Sepp, K. Public Opinions on Oil Shale Mining Heritage and its Tourism Potential. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2015, 15, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loustau, M. Transgressing the Right to the City: Urban Mining and Ecotourism in Post-Industrial Romania. Anthropol. Q. 2020, 93/1, 1555–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triantafyllidis, S.; Psarraki, D. Implementation of geochemical modeling in post-mining land uses, the case of the abandoned open pit lake of the Kirki high sulfidation epithermal system, Thrace, NE Greece. Environ. Earth Sci. 2020, 79, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antic, A.; Peppoloni, S.; Di Capua, G. Applying the Values of Geoethics for Sustainable Speleotourism Development. Geoheritage 2020, 12, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erikstad, L. Geoheritage and geodiversity management—The questions for tomorrow. Proc. Geol. Assoc. 2013, 124, 713–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darulová, J. Traditional culture in tourism using its most important values. In XVIII. Mezinárodní Kolokvium o Regionálních vědách. Sborník Příspěvků. Sborník Příspěvků. 18th International Colloquium on Regional Ciences. Conference Proceedings; Masarykova univerzita: Brno, Czech Republic, 2015; pp. 737–742. ISBN 978-80-10-7861-1. [Google Scholar]

- Hrubalová, L.; Palenčíková, Z. Demand for Creative Tourism in Slovakia. In Proceedings of the 4th International Multidisciplinary Scientific Conference on Social sciences and Arts SGEM2017, Albena, Bulgarian, 24–30 August 2017; pp. 205–212. [Google Scholar]

- Hrubalová, L. Demand and Supply Comparison of Regional Products in Tourism. In Marketing Identity: Brands We Love, Pt II; Petranova, D., Cabyova, L., Bezakova, Z., Eds.; Univ Ss Cyril & Methodius Trnava-Ucm: Trnava, Slovakia, 2016; pp. 339–350. ISBN 978-80-8105-841-7. ISSN 1339-5726. [Google Scholar]

- Duxbury, N. Cultural and creative work in rural and remote areas: An emerging international conversation. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, K.; Ruszkai, C.; Szűcs, A.; Koncz, G. Examining the Role of Local Products in Rural Development in the Light of Consumer Preferences—Results of a Consumer Survey from Hungary. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svoradová, L.; Palkechová, L.; Virágh, R. Rural TOURISM and agrotourism in the Slovak Republic. In Proceedings from VIII. International Conference on Applied Business Research (ICABR 2013); Mendel Univ Brno: Brno, Czechia, 2013; pp. 534–546. [Google Scholar]

- Špulerová, J.; Štefunková, D.; Dobrovodská, M.; Izakovičová, Z.; Kenderessy, P.; Vlachovičová, M.; Lieskovský, J.; Piscová, V.; Petrovič, F.; Kanka, R. Traditional Agricultural Landscapes of Slovakia (In Slovak: Historické Štruktúry Poľnohospodárskej Krajiny Slovenska), 1; VEDA: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lieskovský, J.; Bezák, P.; Špulerová, J.; Lieskovský, T.; Koleda, P.; Dobrovodská, M.; Bürgi, M.; Gimmi, U. The abandonment of traditional agricultural landscape in Slovakia—Analysis of extent and driving forces. J. Rural Stud. 2015, 37, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Špulerová, J.; Drábová, M.; Lieskovský, J. Traditional agricultural landscape and their management in less favoured areas in Slovakia. Ekol. Bratisl. 2016, 35, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bezák, P.; Dobrovodská, M. Role of rural identity in traditional agricultural landscape maintenance: The story of a post-communist country. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2019, 43, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieskovský, J.; Kanka, R.; Bezák, P.; Štefunková, D.; Petrovič, F.; Dobrovodská, M. Driving forces behind vineyard abandonment in Slovakia following the move to a market-oriented economy. Land Use Pol. 2013, 32, 356–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solár, J.; Janiga, M.; Markuljaková, K. The Socioeconomic and Environmental Effects of Sustainable Development in the Eastern Carpathians, and Protecting its Environment. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2016, 25, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otepka, P.; Kučáková, K. Rural Tourism in Oscadnica Village with the Example of Tourism Facility—Cottages in Kysuce Region of Slovakia. Sci. Pap. Ser. Manag. Econ. Eng. Agric. Rural Dev. 2010, 10, 249–254. [Google Scholar]

- Otepka, P.; Nemes, J. Realization of Traditional Sheepherding in Agritourism and Rural Tourism. Sci. Pap. Ser. Manag. Econ. Eng. Agric. Rural Dev. 2010, 10, 255–260. [Google Scholar]

- Králová, K. Proceedings Paper International Scientific Conference on Knowledge for Market Use—People in Economics—Decisions, Behavior and Normative Models. In Clusters and Small and Medium-Sized Businesses; Slavickova, P., Ed.; Univ Palackeho V Olomouci: Olomouc, Czech Republic, 2017; pp. 924–931. ISBN 978-80-244-5233-3. [Google Scholar]

- Székely, V. From enthusiasm to scepticism: Tourism cluster initiatives and rural development in Slovakia. Stud. Agric. Econ. 2014, 116, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gajdošíková, Z.; Gajdošík, T.; Kučerová, J.; Magátová, I. Reengineering of Tourism Organization Structure: The Case of Slovakia. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 230, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Finka, M.; Husár, M.; Sokol, T. Program for Lagging Districts as a Framework for Innovative Approaches within the State Regional Development Policies in Slovakia. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, A.; Gonzalez-Rodriguez, M.R.; Patuleia, M. Developing poor communities through creative tourism. J. Tour. Cult. Chang. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zatori, A.; Smith, M. The Potential for Roma Tourism in Budapest. In Ethnic and Excluded Communities as Tourist Attractions; Diekmann, A., Smith, M.K., Eds.; Minorities, Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2015; pp. 60–85. [Google Scholar]

- Finková, Z. Statistic of Nationalities and Roma (In Slovak: Štatistika národností a Rómovia). Geogr. Časopis 2000, 52, 285–288. [Google Scholar]

- Government Office of the Slovak Republic, Office of the Plenipotentiary of the Slovak Republic Government for a Roma Communities, “Strategy of the Slovak Republic for Integration of Roma up to 2020”. In Bratislava; 2011. Available online: https://www.employment.gov.sk/files/legislativa/dokumenty-zoznamy-pod/strategyoftheslovakrepublicforintegrationof-romaupto2020.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2021).

- Johnson, J.; Snepenger, D.; Akis, S. Residents Perceptions of Tourism Development. Ann. Tour. Res. 1994, 21, 629–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheyvens, R. Linking tourism to the sustainable development goals: A geographical perspective. Tour. Geogr. 2018, 20, 341–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheyvens, R. Ecotourism and the empowerment of local communities. Tour. Manag. 1999, 20, 245–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gertner, R.K. The impact of cultural appropriation on destination image, tourism, and hospitality. Thunderbird Int. Bus. Rev. 2019, 61, 873–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, P. Exploring the cultural landscape of the Obeikei in Ogasawara, Japan. J. Tour. Cult. Chang. 2009, 7, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakic, T.; Chambers, D. Rethinking the Consumption of Places. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 1612–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, S. Diversity, Tourism, and Economic Development: A Global Perspective. Tour. Anal. 2020, 25, 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matlovičová, K.; Kolesárová, J.; Matlovič, R. Pro-Poor Tourism as a Tool for Development of Marginalized Communities (Example of Municipality of Spišský Hrhov) In Michálek, A. Podolák, P. Regions of Poverty in Slovakia. Institute of Geography SAS, 2016. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/298883017_PRO-POOR_turizmus_ako_nastroj_rozvoja_marginalizovanych_komunit_priklad_obce_Spissky_Hrhov (accessed on 24 February 2021).

- Scheyvens, R.; Biddulph, R. Inclusive tourism development. Tour. Geogr. 2018, 20, 589–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilufya, A.; Hughes, E.; Scheyvens, R. Tourists and community development: Corporate social responsibility or tourist social responsibility? J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1513–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, J.; Denman, R.; Hickman, G.; Slovak, J. Rural tourism in Roznava Period: A Slovak case study. Tour. Manag. 2001, 22, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čuka, P. Geography of tourism of Slovakia. In The Geography of Tourism of Central and Eastern European Countries; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 437–465. [Google Scholar]

| Slovak Republic | Revúca | Rimavská Sobota | Rožňava | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic Sign | Inhab. | Inhab. | Per Mille | Inhab. | Per Mille | Inhab. | Per Mille |

| Year-average number of permanent residents | 5,445,089 | 39,870 | 84,313 | 62,271 | |||

| Balance of migration | 3955 | −154 | −3.86 | −107 | −1.27 | −131 | −2.10 |

| Total increase in population | 7301 | −235 | −5.89 | −61 | −0.72 | −49 | −0.79 |

| Number of permanent residents at the end of the year | 5,450,421 | 39,736 | 84,270 | 62,286 | |||

| Unemployment rate (November 2020, %) | 7.35 | 18.16 | 19.73 | 15.44 | |||

| Number of municipalities with Roma population (total municipalities in brackets) | (825) 2927 | (42) 29 | (107) 64 | (62) 36 | |||

| Number of villages that are over half Roma | 160 | 14 | 34 | 8 | |||

| Roma as proportion of population in district towns (%) | 16 | 18 | 12 | ||||

| Slovak Republic | Revúca | Rimavská Sobota | Rožňava | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number and proportion of accommodation facilities | 4487 | 16 (0.35%) | 28 (0.62%) | 71 (1.58%) |

| Number and proportion of overnight stays of visitors in accommodation facilities | 17,703,695 | 53,813 (0.30%) | 101,927 (0.57%) | 51,372 (0.29%) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hutárová, D.; Kozelová, I.; Špulerová, J. Tourism Development Options in Marginal and Less-Favored Regions: A Case Study of Slovakia´s Gemer Region. Land 2021, 10, 229. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10030229

Hutárová D, Kozelová I, Špulerová J. Tourism Development Options in Marginal and Less-Favored Regions: A Case Study of Slovakia´s Gemer Region. Land. 2021; 10(3):229. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10030229

Chicago/Turabian StyleHutárová, Daniela, Ivana Kozelová, and Jana Špulerová. 2021. "Tourism Development Options in Marginal and Less-Favored Regions: A Case Study of Slovakia´s Gemer Region" Land 10, no. 3: 229. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10030229