Vulnerabilities and Threats to Natural Forest Regrowth: Land Tenure Reform, Land Markets, Pasturelands, Plantations, and Urbanization in Indigenous Communities in Mexico

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Vulnerabilities and Threats to Forest Regrowth

1.2. The 1992 (Counter) Agrarian Reform: A New Land Market

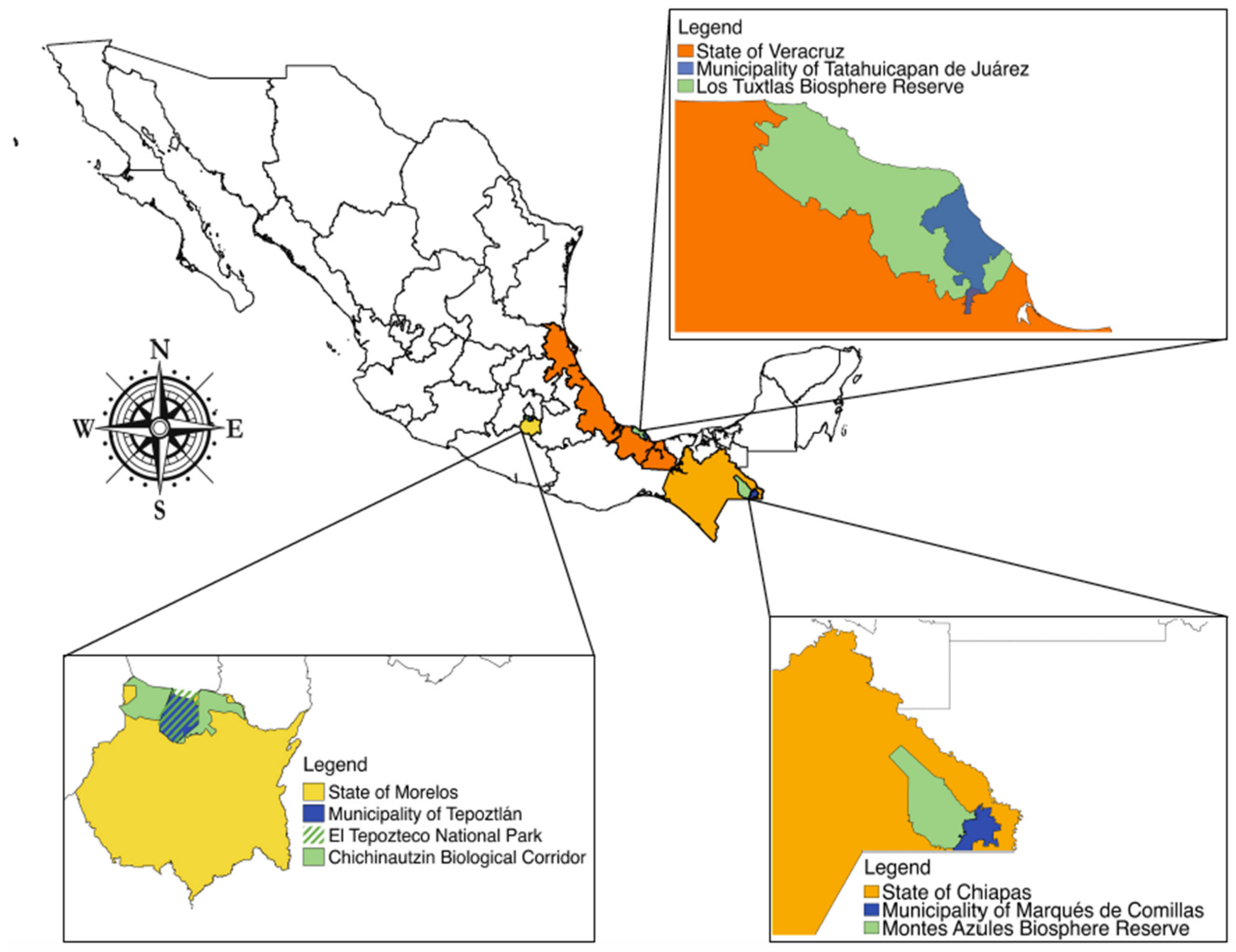

1.3. Case Studies in Veracruz, Chiapas, and Morelos

2. Methods

3. Results

3.1. Can New Land Markets, Natural Regeneration, and Community Political Institutions Coexist with the 1992 Agrarian Reform?

“People from Coatzacoalcos are buying the land, and now they are the new ejido members. Having money allows them to pay for two or three plots, and they set the price. Formerly, ejido members were native to here and participated in the assemblies; the majority participated. Forty or 50 were missing, but up to 400 met. Not anymore; not even a fourth of them come. That takes away our strength. If we want to fight to defend our water and our forests, we don’t have the strength anymore, with so many people from elsewhere who don’t care about our land. They don’t even live here. They just pay a big sum, so somebody takes care of their cattle, but they rarely come. They just buy the land as business”.

“It’s more expensive to produce your own corn than to buy it. The price of maize is low, and you need to invest a lot of work and money to produce it”.

3.2. Land-Use Change and Land-Use Competition

“I saw the opportunity. We asked for timber permits; we came with the wish to clear the land and make use of the timber but also with the wish to have our cattle. We had good harvests, but we didn’t have money. In those days, there was poverty of money. I saved, but I had to cut everything down to put cattle in. I just left a few trees for shade. We don’t want to let trees grow because then the grasses don’t grow.”

3.3. Contradictory Environmental Policies: Top-Down Decisions

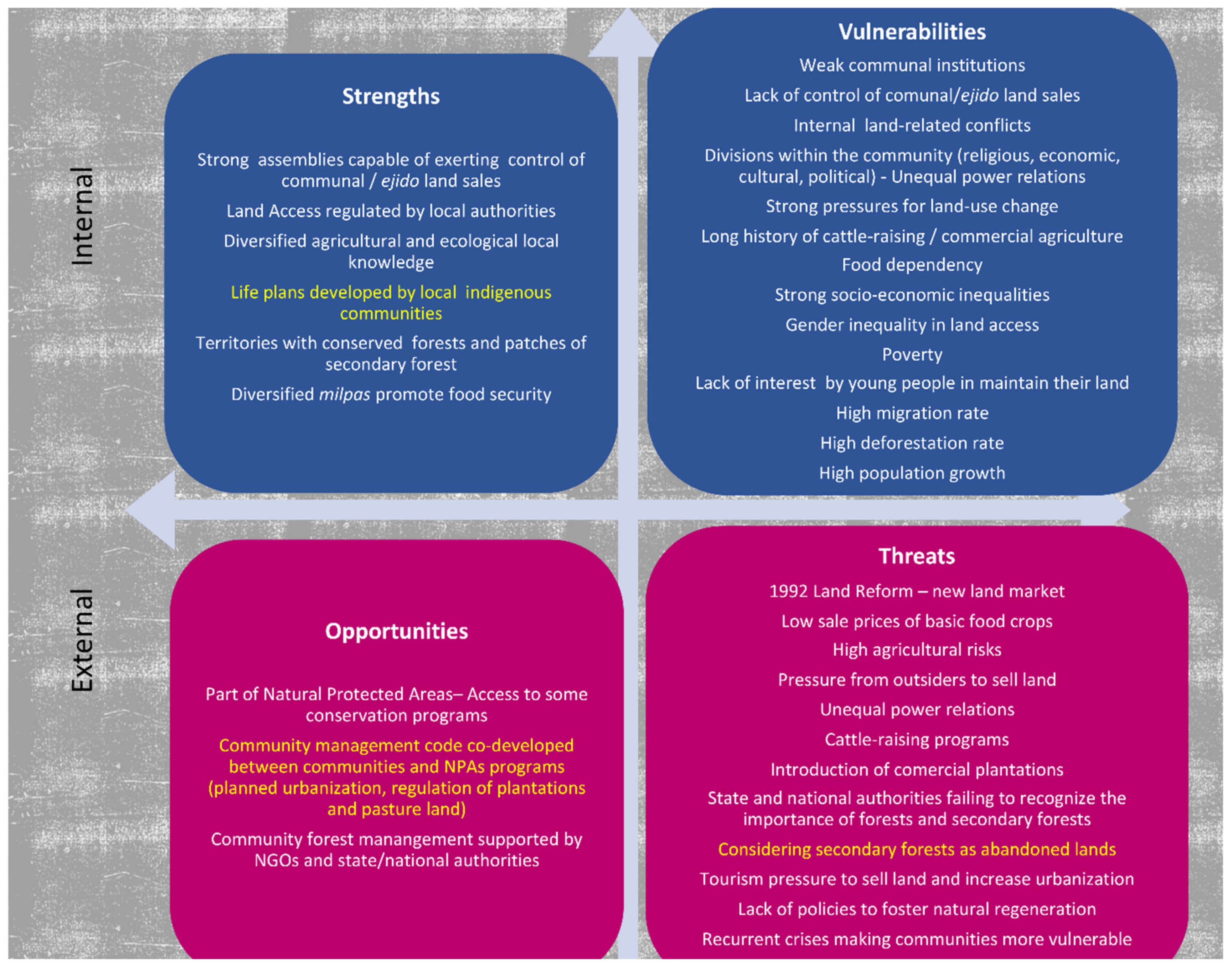

3.4. Strengths, Vulnerabilities, Opportunities, and Threats for Natural Regeneration

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The concept of vulnerability originated in diverse disciplines and theoretical frameworks regarding disasters such as famines and climate change. Human ecology highlights adaptation, consensus, and strategies to overcome vulnerabilities, while Political Economy and Political Ecology emphasize differentiated vulnerabilities of social classes with unequal access to resources and power. Considering these perspectives, as well as the definition by the International Strategy for Disaster Reduction [119,120], we consider vulnerability to be the degree to which a political and socio-economic system, together with lack of physical and ecological assets, creates susceptibility to disasters. Vulnerability is determined by a combination of the following factors: socio-economic, ecological, political, and cultural conditions of human settlements; public policies and government administration; socio-economic inequities and lack of organized capacities in disaster and risk management. As stated by the ISDR (119, Item 9:6), “The specific dimensions of social, economic and political vulnerabilities are also related to inequalities, gender relations, economic patterns, and ethnic and racial divisions”. Reaffirming the idea that vulnerability is linked to “lack of freedom—the freedom to influence the political economy that shapes entitlements”, such as rights to assets and social protection [121,122]. |

| 2 | The ejido land tenure system resulted from the Mexican Revolution and was recognized by the 1917 Constitution (Section 3.1 discusses its characteristics). The communal land tenure system was recognized by the Spanish Crown during the colonial era as land belonging to indigenous communities. Some communities with communal land tenure have divided their land into family or individual plots, while others have maintained all or part of their land as a common. |

| 3 | The most common vegetation types are high and medium rainforest (1873 species reported); mangroves (98 species); cloud forest (786 species); pine and oak forest (732 species); savanna (146 species); coastal dunes (315 species); fallows (249 species), and secondary forests (283 species; [123]). |

| 4 | As the Programa de Desmontes and Programa de Colonización del Trópico. |

| 5 | In such a contract, a landowner cares for the livestock of another person, providing inputs for land where the animals are raised, while the owner of the animals provides any medicines necessary. Newborns are divided equally between both parties. |

References

- Chazdon, R.L.; Guariguata, M.R. Natural regeneration as a tool for large-scale forest restoration in the tropics: Prospects and challenges. Biotropica 2016, 48, 716–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo-Rodríguez, V.; Melo, F.P.; Martínez-Ramos, M.; Bongers, F.; Chazdon, R.L.; Meave, J.A.; Norden, N.; Santos, B.A.; Leal, I.R.; Tabarelli, M. Multiple successional pathways in human-modified tropical landscapes: New insights from forest succession, forest fragmentation and landscape ecology research. Biol. Rev. 2017, 92, 326–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansourian, S. Governance and forest landscape restoration: A framework to support decision-making. J. Nat. Conserv. 2017, 37, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chazdon, R.L.; Wilson, S.J.; Brondizio, E.; Guariguata, M.R.; Herbohn, J. Key challenges for governing forest and landscape restoration across different contexts. Land Use Policy 2021, 104, 104854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouzeilles, R.; Barros, F.S.; Chazdon, R.L.; Ceccon, E.; Adams, C.; Lazos-Chavero, E.; Monteiro, L.; Junqueira, A.B.; Strassburg, B.B.; Guariguata, M.R.; et al. Associations between socio-environmental factors and landscape-scale biodiversity recovery in naturally regenerating tropical and subtropical forests. Conserv. Lett. 2021, 14, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, D.; Erskine, P.D.; Parrotta, J.A. Restoration of degraded tropical forest landscapes. Science 2005, 310, 1382–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nagendra, H. Drivers of reforestation in human-dominated forests. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 15218–15223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Composto, C.; Navarro, M. Estados, transnacionales extractivas y comunidades movilizadas: Dominación y resistencias en torno de la minería a gran escala en América Latina. Theomai 2012, 25, 58–78. [Google Scholar]

- Sunderlin, W.D.; Larson, A.M.; Duchelle, A.E.; Resosudarmo, I.A.; Huynh, T.B.; Awono, A.; Dokken, T. How are REDD+ Proponents Addressing Tenure Problems? Evidence from Brazil, Cameroon, Tanzania, Indonesia, and Vietnam. World Dev. 2014, 55, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, M.L. Luchas Por lo Común. Antagonismo Social Contra el Despojo Capitalista de Los Bienes Naturales en México; Instituto de Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades “Alfonso Vélez Pliego”: Mexico City, Mexico, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Mazuera, G. ¿Tierras ejidales como mercancía o como territorio indígena? Intermediación legal y nuevas interpretaciones disonantes de la legislación agraria en el México contemporáneo, Caravelle. Cah. Monde Hisp. Luso-Brésilien 2019, 112, 95–108. [Google Scholar]

- Brondizio, E.S.; Ostrom, E.; Young, O.R. Connectivity and the Governance Of Multilevel Social-Ecological Systems: The Role of Social Capital. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2009, 34, 253–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, A.M.; Brockhaus, M.; Sunderlin, W.D.; Duchelle, A.; Babon, A.; Dokken, T.; Pham, T.T.; Resosudarmo, I.A.; Selaya, G.; Awono, A.; et al. Land tenure and REDD+: The good, the bad and the ugly. Glob. Environ. Change 2013, 23, 678–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFries, R.; Rudel, T.; Uriarte, M.; Hansen, M. Deforestation driven by urban population growth and agricultural trade in the twenty-first century. Nat. Geosci. 2010, 3, 178–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, E.A.; Hernández-Gómez, I.U.; Romero-Montero, J.A. Los procesos y causas del cambio en la cobertura forestal de la Península Yucatán, México. Ecosistemas 2017, 26, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLain, R.; Lawry, S.; Guariguata, M.R.; Reed, J. Toward a Tenure-Responsive Approach to Forest Landscape Restoration: A Proposed Tenure Diagnostic for Assessing Restoration Opportunities Land Use Policy. 2021. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0264837718303855?via%3Dihub (accessed on 30 September 2021). [CrossRef]

- Wright, S.; Muller-Landau, H.; Schipper, L. The future of tropical species on a warmer planet. Conserv. Biol. 2009, 23, 1418–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, M.E.; McAlpine, C.A.; House, P.N.; Smith, G.C. Regrowth forests on abandoned agricultural land: A review of their habitat values for recovering forest fauna. Biol. Conserv. 2007, 140, 273–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filotas, E.; Parrott, L.; Burton, P.J.; Chazdon, R.L.; Coates, K.D.; Coll, L.; Haeussler, S.; Martin, K.; Nocentini, S.; Puettmann, K.J.; et al. Viewing forests through the lens of complex systems science. Ecosphere 2014, 5, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazoul, J.; Chazdon, R.L. Degradation and recovery in changing forest landscapes: A multiscale conceptual framework. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2017, 42, 161–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rozendaal, D.M.; Bongers, F.; Aide, T.M.; Alvarez-Dávila, E.; Ascarrunz, N.; Balvanera, P.; Becknell, J.M.; Bentos, T.V.; Brancalion, P.H.; Cabral, G.A. Biodiversity recovery of neotropical secondary forests. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hernández-Xolocotzi, E.; Levy-Tacher, S.I.; Bello-Baltazar, Y.E. La roza-tumba-quema en Yucatán. In La Milpa en Yucatán: Un Sistema de Producción Agrícola Tradicional; Colegio de México: Mexico City, Mexico, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Metzger, J.P. Landscape dynamics and equilibrium in areas of slash-and-burn agriculture with short and long fallow period (Bragantina region, NE Brazilian Amazon). Landsc. Ecol. 2002, 17, 419–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy-Tacher, S.I.; Ramírez-Marcial, N.; Navarrete-Gutiérrez, D.A.; Rodríguez-Sánchez, P.V. Are Mayan community forest reserves effective in fulfilling people’s needs and preserving tree species? J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 245, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigh, R.; Ford, A. El Jardín Forestal Maya: Ocho Milenios de Cultivo Sostenible de los Bosques Tropicales; Fray Bartolomé de las Casas: Mexico City, Mexico, 2019; p. 283. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver-Smith, A. Anthropological research on hazards and disasters. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 1996, 25, 303–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, P.; Dietz, T. Structure, agency and environment: Toward an integrated perspective on vulnerability. Glob. Environ. Change 2008, 18, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilches-Chaux, G. Desastres, Ecologismo y Formación Profesional; SENA: Bogota, Colombia, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Blaikie, P.; Cannon, T.; Davis, I.; Wisner, B. At Risk: Natural Hazards, People’s Vulnerability and Disasters; Routledge: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Hecht, S.B.; Morrison, K.D.; Padoch, C. The Social Lives of Forests. Past, Present, and Future of Woodland Resurgence; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Li, X. Global understanding of farmland abandonment: A review and prospects. J. Geogr. Sci. 2017, 27, 1123–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiGiano, M.; Ellis, E.; Keys, E. Changing landscapes for forest commons: Linking landtenure with forest cover change following Mexico’s 1992 Agrarian counter-reforms. Hum. Ecol. 2013, 41, 707–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (SEMARNAT). Compendio de Superficie Reforestada. Available online: https://apps1.semarnat.gob.mx:8443/dgeia/compendio_2016/archivos/01_rforestales/D3_RFORESTA09_06.pdf (accessed on 8 October 2021).

- Comisión Nacional Forestal (CONAFOR). Estimación de la Tasa de Deforestación en México Para el Periodo 2001–2018 Mediante el Método de Muestreo. Documento Técnico; Comisión Nacional Forestal (CONAFOR): Zapopan, Mexico, 2020.

- Comisión Nacional Forestal (CONAFOR). Inventario Nacional Forestal y de Suelos. Informe de Resultados 2009–2014; Comisión Nacional Forestal (CONAFOR): Mexico City, Mexico, 2018.

- UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Evaluación de los Recursos Forestales Mundiales 2020; UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Marcus, G.E. Ethnography in/of the world system: The emergence of multi-sited Ethnography. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 1995, 24, 95–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warman, A. La reforma al Artículo 27 Constitucional. Estud. Agrar. Rev. Procur. Agrar. 1996, 2, 9–19. [Google Scholar]

- Mackinlay, H. Las reformas de 1992 a la legislación agraria. El fin de la Reforma Agraria mexicana y la privatización del ejido. Polis 1993, 93, 99–127. [Google Scholar]

- Janvry, A.; Gordillo, G.; Sadoulet, E. Mexico’s Second Agrarian Reform: Household and Community Response, 1990–1994; University of California: San Diego, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Deere, C.D.; Leon, M. Gender, land and water: From reform to counter-reform in Latin America. Agric. Hum. Values 1998, 15, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zepeda, G. Transformación Agraria: Los Derechos de Propiedad en el Campo Mexicano bajo un Nuevo Marco Institucional, Mexico; CIDAC: Lisbon, Portugal, 2000; p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, G. The evolution and resilience of community-based land tenure in rural Mexico. Land Use Policy 2009, 26, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haenn, N. The changing and enduring ejido: A state and regional examination of Mexico’s landland tenure counter-reforms. Land Use Policy 2006, 23, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, D.B.; Antinori, C.; Torres-Rojo, J.M. The mexican model of community forest management: The role of agrarian policy, forest policy and entrepreneurial organization. For. Policy Econ. 2006, 8, 470–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazos, E. La Ganaderización de dos Comunidades Veracruzanas: Condiciones de la Difusión de un Modelo Agrario. In El Ropaje de la Tierra. Naturaleza y Cultura en Cinco Zonas Rurales; Paré, L., Sánchez, M.J., Eds.; IIS-UNAM/Plaza y Valdes: Mexico City, Mexico, 1996; pp. 177–242. [Google Scholar]

- Durand, L.; Lazos, E. Colonization and tropical deforestation in Sierra Santa Marta, Southern Mexico. Environ. Conserv. 2004, 31, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durand, L.; Lazos, E. The local perception of tropical deforestation and its relation to conservation policies in Los Tuxtlas Biosphere Reserve, Mexico. Hum. Ecol. An. Interdiscip. J. 2008, 36, 323–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secretaría de Finanzas y Planeación de Veracruz (SEFIPLAN Veracruz), Cuenta Pública 2018. SEFIPLAN Veracruz, Gobierno del estado de Veracruz: Veracruz, Mexico. 2018. Available online: http://www.veracruz.gob.mx/finanzas/transparencia/transparencia-proactiva/contabilidad-gubernamental/cuenta-publica/cuenta-publica-2018/ (accessed on 8 October 2021).

- Ramírez, R.F. Conservación de la Biodiversidad en la Región de Los Tuxtlas, Veracruz; Charleton University: Mexico City, Mexico, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Soto, M. El Clima. In Los Tuxtlas. El Paisaje de la Sierra; Guevara, S., Laborde, J., Sánchez-Ríos, G., Eds.; Instituto de Ecología A.C. and European Union: Veracruz, Mexico, 2006; pp. 195–200. [Google Scholar]

- Buckles, D.J. Cattle, Corn and Conflict in the Mexican Tropics; Carleton University: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Velázquez, E. Política, ganadería y recursos naturales en el trópico húmedo veracruzano: El caso del municipio de Mecayapan. Relac. Estud. Hist. Soc. 1992, XII, 23–63. [Google Scholar]

- Lazos, E.; Godínez, L. Dinámica familiar y el inicio de la ganadería en tierras campesinas del sur de Veracruz. In El Ropaje de la Tierra. Naturaleza y Cultura en Cinco Zonas Rurales; Paré, L., Sánchez, M.J., Eds.; IIS-UNAM Plaza y Valdés: Mexico City, Mexico, 1996; pp. 243–354. [Google Scholar]

- Barrera, N.; López, C.; Palma, R. Vacas, pastos y bosques en Veracruz: 1950–1990. In Desarrollo y Medio Ambiente en Veracruz. Impactos Económicos, Ecológicos y Culturales de la Ganadería en Veracruz; Barrera, N., Rodríguez, H., Eds.; CIESAS-Golfo, Instituto de Ecología y Friedrich Ebert Stiftung: Mexico City, Mexico, 1993; pp. 35–71. [Google Scholar]

- Challenger, A.; Soberón, J. Los Ecosistemas Terrestres; CONABIO: Mexico City, Mexico, 2008; Volume 1.

- Lazos, E. Vulnerabilidades en el campo mexicano: Ruptura del territorio agroalimentario en la Sierra de Santa Marta, sur de Veracruz, México. Aliment. Salud Sustentabilidad 2020, 179–208. Available online: http://www.humanindex.unam.mx/humanindex/consultas/detalle_capitulos.php?id=31344&rfc=TEFDRTYwMDEwMg==&idi=1 (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- De Vos, J. Una tierra para sembrar sueños. In Historia Reciente de la Selva Lacandona 1950–2000; Fondo de Cultura Económica: Mexico City, Mexico, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Castro, E.; de la Maza, J.; Meli, P.; Carabias, J. Colonización e instituciones gubernamentales en el municipio de Marqués de Comillas. In Conservación y Desarrollo Sustentable en la Selva Lacandona. 25 Años de Actividades y Experiencias; Carabias, J., de la Maza, J., Cadena, R., Eds.; Natura y Ecosistemas Mexicanos A.C.: Mexico City, Mexico, 2015; pp. 211–218. [Google Scholar]

- González-Ponciano, J. Marqués de Comillas: Cultura y sociedad en la selva fronteriza México-Guatemala. In Chiapas los Rumbos de Otra Historia; Viqueira, J.P., Ruz, H.M., Eds.; UNAM-CIESAS: Mexico City, Mexico, 1996; pp. 425–444. [Google Scholar]

- De Jong, B.H.; Ochoa-Gaona, S.; Castillo-Santiago, M.A.; Ramírez-Marcial, N.; Cairns, M.A. Carbon flux and patterns of land-use/land-cover change in the Selva Lacandona, Mexico. Ambio 2000, 29, 504–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, N. La Remunicipalización en Marqués de Comillas y Benemérito de Las Américas, Chiapas: Entre la Vía Institucional y la Vida Cotidiana; CIESAS: Mexico City, Mexico, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, N. Benemérito de las Américas y Marqués de Comillas; Gobierno del Estado de Chiapas: Tuxtla Gutiérrez, Mexico, 2006; p. 235. [Google Scholar]

- Registro Agrario Nacional (RAN). Estructura de la Propiedad Social. In Mensual; Registro Nacional Agrario (RAN): Morelia, Mexico, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Consejo Nacional de Evaluación de la Política de Desarrollo Social (CONEVAL). Informe Anual Sobre La Situación de Pobreza y Rezago Social, Marqués de Comillas, Chiapas; Consejo Nacional de Evaluación de la Política de Desarrollo Social (CONEVAL) y Secretaría de Desarrollo Social (SEDESOL): Mexico City, Mexico, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lazos, E. Ciclos y rupturas: Dinámica ecológica de la ganadería en el sur de Veracruz. In Historia Ambiental de la Ganadería en México; Hernández, L., Ed.; Institut Recherche Développement: Durango, Mexico, 2001; pp. 133–153. [Google Scholar]

- Paré, L.; Lazos, E. Escuela Rural y Organización Comunitaria: Instituciones Locales para el Desarrollo y el Manejo Ambiental; IIS-UNAM/Plaza y Valdés: Mexico City, Mexico, 2003; p. 405. [Google Scholar]

- Meli, P.; Hernández, G.; Castro, E.; Carabias, J. Vinculando paisaje y parcela: Un enfoque multi-escala para la restauración ecológica en áreas rurales. Investig. Ambient. 2015, 7, 43–53. [Google Scholar]

- Meli, P.; Aguilar-Fernández, R.; Carabias, J. Restauración ecológica en Marqués de Comillas. In Conservación y Desarrollo Sustentable en la Selva Lacandona. 25 Años de Actividades y Experiencias; Carabias, J., de la Maza, J., Cadena, R., Eds.; Natura y Ecosistemas Mexicanos A.C.: Mexico City, Mexico, 2015; pp. 429–458. [Google Scholar]

- Meli, P.; Martínez-Ramos, M.; Rey-Benayas, J.M.; Carabias, J. Combining ecological, social, and technical criteria to select species for forest restoration. Appl. Veg. Sci. 2014, 17, 744–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Meli, P.; Rey-Benayas, J.M.; Martínez-Ramos, M.; Carabias, J. Effects of grass clearing and soil tilling on establishment of planted tree seedlings in tropical riparian pastures. New For. 2015, 46, 507–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar, R.; Meli, P.; Carabias, J. Modelos de restauración ecológica para la recuperación de servicios ecosistémicos. In Conservación y Desarrollo Sustentable en la Selva Lacandona; Carabias, J., Cadena, R., de la Maza, J., Castro, E., Eds.; Natura y Ecosistemas Mexicanos A.C.: Mexico City, Mexico, 2021; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar, R. Análisis de los Componentes Socioambientales Para la Restauración de Claros Antropogénicos en la Selva Tropical Húmeda, Marqués de Comillas, Chiapas. Ph.D. Thesis, Facultad de Ciencias, UNAM, Mexico City, Mexico, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bilbatúa, K. Diagnóstico de la Vegetación de Amatlán, Morelos, Mexico, con Fines de Conservación y Restauración; Maestría en Ciencias Biológicas, UNAM: Mexico City, Mexico, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Suárez, B. Caracterización de la Vegetación del Sotobosque en Amatlán de Quetzalcóatl, Tepoztlán, Morelos; Facultad de Ciencias, UNAM: Mexico City, Mexico, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cayetano, R. Avifauna de Amatlán de Quetzalcóatl, Tepoztlán, México; Facultad de Estudios Superiores Iztacala, UNAM: Mexico City, Mexico, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Núñez-Cruz, A.; Meave, J.A.; Bonfil, C. Reproductive phenology and seed germination in eight tree species from a seasonally dry tropical forest of Morelos, Mexico, implications for community-oriented restoration and conservation. Trop. Conserv. Sci. 2018, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calzada, L.; Meave, J.A.; Bonfil, C.; Figueroa, F. Lands at risk: Land use/land cover change in two contrasting tropical dry regions of Mexico. Appl. Geogr. 2018, 99, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puente-Uribe, B.; Calzada, L.; Bonfil, C.; Figueroa, F. Prácticas agrícolas y conservación de la agrobiodiversidad en Amatlán de Quetzalcóatl. In La Biodiversidad en Morelos. Estudio de Estado 2; CONABIO: Mexico City, Mexico, 2020; Volume III, pp. 428–433. [Google Scholar]

- Puente-Uribe, B. Transformación Agrícola y su Contexto Socioambiental en Amatlán de Quetzalcóatl, Morelos; Maestría en Ciencias de la Sostenibilidad, UNAM: Mexico City, Mexico, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Registro Agrario Nacional (RAN). Ejido de Tatahuicapan de Juárez. Available online: https://phina.ran.gob.mx/index.php (accessed on 8 October 2021).

- Lazos, E.; Jiménez, M. Vulnerabilidades rurales a partir del envejecimiento entre nahuas del sur de Veracruz. TRACE 2021, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Corbera, E.; Kosoy, N.; Martínez, M. Equity implications of marketing ecosystem services in protected areas and rural communities: Case studies from Meso-America. Glob. Environ. Change 2007, 17, 365–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuitjen, M. Family Property and the Limits of Intervention: The Article 27 Reforms and the PROCEDE Programme in Mexico. Develop. Change 2003, 34, 475–497. [Google Scholar]

- Castellanos-Navarrete, A.; Jansen, K. Oil palm expansion without enclosure: Smallholders and environmental narratives. J. Peasant. Stud. 2015, 42, 791–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Ángel-Mobarak, G.A. La Comisión Nacional Forestal en la Historia y el Futuro de la Política Forestal de México; Centro de Investigación y Docencia Económicas CONAFOR: Mexico City, Mexico, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias, L.; Martínez, E.R.; Graf, S.; Muñoz-Piña, C.; Gutiérrez, J.; Flores, F.; Bauche, P.; Iglesias, L.; Martínez, E.R.; Graf, C.; et al. Patrimonio Natural de México. Cien Casos de Éxito; Carabias, J.S., de la Maza, J., Galindo, C., Eds.; CONABIO: Mexico City, Mexico, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Romo-Cruz, D. Factores Socioambientales Asociados a la Urbanización en el Municipio de Tepoztlán, Morelos (1985–2015); Maestría en Ciencias de la Sostenibilidad, UNAM: Mexico City, Mexico, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, G. Subsidios Destinados al Sector Ganadero, el Caso del PROGAN 2008. 2013. Available online: www.subsidiosalcampo.org (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Geografía e Informática (INEGI), Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave (30). Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/areasgeograficas/?ag=30 (accessed on 8 October 2021).

- Guevara, S.; Laborde, J.; Sánchez-Ríos, G. Los Tuxtlas. El Paisaje de la Sierra; Instituto de Ecología: Veracruz, Mexico, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Von Thaden, J.J.; Laborde, J.; Guevara, S.; Mokondoko-Delgadillo, P. Dinámica de los cambios en el uso del suelo y cobertura vegetal en la Reserva de la Biosfera Los Tuxtlas (2006–2016). Rev. Mex. Biodivers. 2020, 91, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proyecto Sierra de Santa Marta A.C. (PSSM). Actualización de la Tasa de Cambio del Uso de Suelo en la Reserva de la Biosfera Los Tuxtlas, Informe Final; Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas: Baja California, Mexico, 2011.

- Mendoza, E. Análisis de la Deforestación de la Selva Lacandona: Patrones, Magnitud y Consecuencias; Facultad de Ciencias, UNAM: Mexico City, Mexico, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- González, M.A.; Carabias, J.; Auzias, C.; Castro, E.; Acevedo, M.A. Ordenamiento Comunitario del Territorio de la Microrregión Marqués de Comillas: Una Iniciativa Interejidal para el Mejoramiento de los Medios de Vida Rurales en la Selva Lacandona; Grupo Autónomo para la Investigación Ambiental: Oaxaca, Mexico, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Obregón, R. Programa Preliminar de Desarrollo Agroecológico del Municipio Marqués de Comillas; CBM–Conabio: Mexico City, Mexico, 2007.

- Hernandez-Rojas, D.A.; Lopez-Barrera, F.; Bonilla-Moheno, M. Análisis preliminar de la dinámica de uso del suelo asociada al cultivo palma de aceite (Elaeis guineensis) en México. Agrociencia 2018, 52, 875–889. [Google Scholar]

- SIAP-SAGARPA. Superficies de Siembra de Cultivos Perennes y de Temporal (2006–2016). Available online: http://infosiap.siap.gob.mx/gobmx/datosAbiertos_a.php (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- Castellanos-Navarrete, A. Oil palm on peasant lands: The politics of territorial transformations in Chiapas, Mexico. Rev. Pueblos Front. Digit. 2018, 13, 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- De la Maza, J.; Mastretta, A.; Ruiz, L.; Carabias, J. Ecoturismo para la conservación. In Conservación y Desarrollo Sustentable en la Selva Lacandona. 25 Años de Actividades y Experiencias; Carabias, J., de la Maza, J., Cadena, R., Eds.; Natura y Ecosistemas Mexicanos A.C.: Mexico City, Mexico, 2015; pp. 333–352. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz, R.; Straffon, S.; de la Maza, J.; Carabias, J. Historia y análisis de la UMA extensiva de mariposas La Casa del Morpho. In Conservación y Desarrollo Sustentable en la Selva Lacandona. 25 Años de Actividades y Experiencias; Carabias, J., de la Maza, J., Cadena, R., Eds.; Natura y Ecosistemas Mexicanos A.C.: Mexico City, Mexico, 2015; pp. 375–394. [Google Scholar]

- Valadez, V.; Carabias, J.; Noriega, D.; Ramírez, J.J.; Barceinas, A.; de la Maza, J. Empresas ecoturísticas sociales que operan en Marqués de Comillas. In Conservación y Desarrollo Sustentable en la Selva Lacandona. 25 Años de Actividades y Experiencias; Carabias, J., de la Maza, J., Cadena, R., Eds.; Natura y Ecosistemas Mexicanos A.C.: Mexico City, Mexico, 2015; pp. 353–374. [Google Scholar]

- Equihua-Elias, G.C.; Messina-Fernández, S.R.; Ramírez-Silva, J. Los pueblos mágicos: Una visión crítica sobre su impacto en el desarrollo sustentable del turismo. Rev. Fuente 2015, 22, 2–7. [Google Scholar]

- Comisión Nacional Forestal (CONAFOR). Reglas de Operación del Programa Apoyos Para el Desarrollo Forestal Sustentable. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/conafor/documentos/reglas-de-operacion-2021?idiom=es (accessed on 11 October 2021).

- UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Secretaría de Agricultura, Ganadería y Desarrollo Rural, Pesca y Alimentación (SAGARPA), Evaluación Nacional de Resultados 2013. Componente Producción Pecuaria Sustentable y Ordenamiento Ganadero y Apícola. 2015. Available online: https://inehrm.gob.mx/recursos/Libros/SAGARPA.pdf (accessed on 9 October 2021).

- FAO-SAGARPA. Evaluación Nacional de Resultados 2013. Componente Producción Pecuaria Sustentable y Ordenamiento Ganadero y Apícola. 2015. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/331642091_Evaluacion_Nacional_de_Resultados_2013_Componente_Produccion_Pecuaria_Sustentable_y_Ordenamiento_Ganadero_y_Apicola_PROGAN (accessed on 9 October 2021).

- Padrón Ganadero Nacional (PGN). Available online: http://pgn.org.mx/consultaPgn.html (accessed on 8 October 2021).

- Secretaría de Obras Públicas, Desarrollo Urbano y Vivienda (SECODUVI). Programa Municipal de Desarrollo Urbano de Tepoztlán; Gobierno del Estado de Morelos: Cuernavaca, Mexico, 2016; pp. 1–58.

- Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas (CONANP). El Tepozteco. Available online: https://simec.conanp.gob.mx/ficha.php?anp=71®=7 (accessed on 8 October 2020).

- Bray, D.; Merino, L.; Barry, D. El manejo comunitario en sentido estricto: Las empresas forestales comunitarias de México. In Los Bosques Comunitarios de México. Manejo Sustentable de Paisajes Forestales; Barton, D., Merino, L., Barry, D., Eds.; Instituto Nacional de Ecología: Mexico City, Mexico, 2007; pp. 21–50. [Google Scholar]

- Nagendra, H.; Ostrom, E. Polycentric governance of multifunctional forested landscapes. Int. J. Commons 2012, 6, 104–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansourian, S. Disciplines, sectors, motivation and power relations in forest landscape restoration. Ecol. Restor. 2021, 39, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonfil, C.; Barrales-Alcalá, B.; Mendoza-Hernández, P.E.; Alavez-Vargas, M.; García-Barrios, R. Los límites sociales del manejo y la restauración de ecosistemas: Una historia en Morelos. In Experiencias Mexicanas en la Restauración de los Ecosistemas; Ceccon, E., Martínez-Garza, E., Eds.; Centro Regional de Investigaciones Multidisciplinarias: Mexico City, Mexico, 2016; pp. 322–345. [Google Scholar]

- Elias, M.; Joshi, D.; Meinzen-Dick, R. Restoration for whom, by whom? A feminist political ecology of restoration. Ecol. Restor. 2021, 39, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, S.; Eckerberg, K. A policy analysis perspective on ecological restoration. Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, E.; Estrada, E.I. Introducción: ¿cultivar el territorio maya? In Cultivar el Territorio Maya: Conocimientos y Organización Social en el Uso de la Selva; Bello, E., Estrada, E.I., Eds.; El Colegio de la Frontera Sur. Red de Espacios de Innovación Socioambiental, Universidad Iberoamericana: Mexico City, Mexico, 2011; pp. 15–44. [Google Scholar]

- Lazos, E. Du Maïs à L’orange: La Transformation de la Structure Agraire. Développement et Crise dans une Région Mexicaine (Oxkutzcab, Yucatan). Ph.D. Thesis, EHESS, Paris, France, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Romero, M.A. Conflictos agrarios, historia y peritajes paleográficos. Reflexionando desde Oaxaca. Estud. Agrar. 2011, 47, 65–84. [Google Scholar]

- ISDR (International Strategy for Disaster Reduction). Living With Risk: A Global Review of Disaster Reduction Initiatives; Inter-Agency Secretariat of the ISDR, United Nations: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Wisner, B.; Blaikie, P.; Cannon, T.; Davis, I. Part III Towards a safer environment. In At Risk: Natural Hazards, People’s Vulnerability and Disasters; Blaikie, P., Cannon, T., Davis, I., Wisner, B., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 1994; pp. 246–321. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. Poverty and Famines An Essay on Entitlement and Deprivation; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1981; p. 257. [Google Scholar]

- Ribot, J. Cause and response:vulnerability and climate in the Anthropocene. J. Peasant. Stud. 2014, 41, 667–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Campos, G.; Laborde, J. La vegetación. In Los Tuxtlas. El Paisaje de la Sierra; Guevara, S., Laborde, J., Sánchez-Ríos, G., Eds.; Instituto de Ecología: Veracruz, Mexico, 2006; pp. 231–271. [Google Scholar]

| Year | Area Deforested Nationwide (ha) | Area Reforested Nationwide (ha) | Area Reforested Area in Chiapas (ha) | Area Reforested in Morelos (ha) | Area Reforested in Veracruz (ha) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 225,151 | 3594 | 5438 | 16,812 | |

| 2001 | 79,672 | 164,823 | 646 | 4737 | 12,208 |

| 2002 | 191,071 | 224,772 | 9361 | 3345 | 15,615 |

| 2003 | 185,741 | 186,715 | 7042 | 6422 | 21,241 |

| 2004 | 135,953 | 195,819 | 6843 | 2304 | 15,093 |

| 2005 | 170,421 | 182,674 | 6902 | 2684 | 25,299 |

| 2006 | 98,853 | 212,675 | 11,215 | 3529 | 26,386 |

| 2007 | 131,822 | 341,376 | 17,669 | 3623 | 3817 |

| 2008 | 192,631 | 373,003 | 16,337 | 5292 | 25,641 |

| 2009 | 301,792 | 176,906 | 11,716 | 5095 | 18,958 |

| 2010 | 220,489 | 136,123 | 22,219 | 2823 | 15,257 |

| 2011 | 282,431 | 231,256 | 18,946 | 774 | 3099 |

| 2012 | 324,262 | 375,706 | 17,576 | 6596 | 24,633 |

| 2013 | 254,855 | 121,005 | 11,182 | 4741 | 9652 |

| 2014 | 342,899 | 128,086 | 16,354 | 6255 | 4987 |

| 2015 | 295,119 | 98,692 | 12,823 | 5801 | 3846 |

| 2016 | 350,298 | 9198 | 4723 | 5241 | |

| 2017 | 3884 | 2808 | 1389 | ||

| Total | 3,558,309 | 3,374,782 | 209,322 | 81,148 | 312,571 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lazos-Chavero, E.; Meli, P.; Bonfil, C. Vulnerabilities and Threats to Natural Forest Regrowth: Land Tenure Reform, Land Markets, Pasturelands, Plantations, and Urbanization in Indigenous Communities in Mexico. Land 2021, 10, 1340. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10121340

Lazos-Chavero E, Meli P, Bonfil C. Vulnerabilities and Threats to Natural Forest Regrowth: Land Tenure Reform, Land Markets, Pasturelands, Plantations, and Urbanization in Indigenous Communities in Mexico. Land. 2021; 10(12):1340. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10121340

Chicago/Turabian StyleLazos-Chavero, Elena, Paula Meli, and Consuelo Bonfil. 2021. "Vulnerabilities and Threats to Natural Forest Regrowth: Land Tenure Reform, Land Markets, Pasturelands, Plantations, and Urbanization in Indigenous Communities in Mexico" Land 10, no. 12: 1340. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10121340

APA StyleLazos-Chavero, E., Meli, P., & Bonfil, C. (2021). Vulnerabilities and Threats to Natural Forest Regrowth: Land Tenure Reform, Land Markets, Pasturelands, Plantations, and Urbanization in Indigenous Communities in Mexico. Land, 10(12), 1340. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10121340