Resilience and Circularity: Revisiting the Role of Urban Village in Rural-Urban Migration in Beijing, China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Informality or Resilience? The Linkage between Urban Villages and Migration

2.1. Urban Village as Informality from a Dualistic Rural vs. Urban Land Use Perspective

2.2. Urban Village as Resilience from a Rural-Urban Circular Migration Perspective

3. Rural Migrants’ Transitory Stays in Beijing Urban Villages

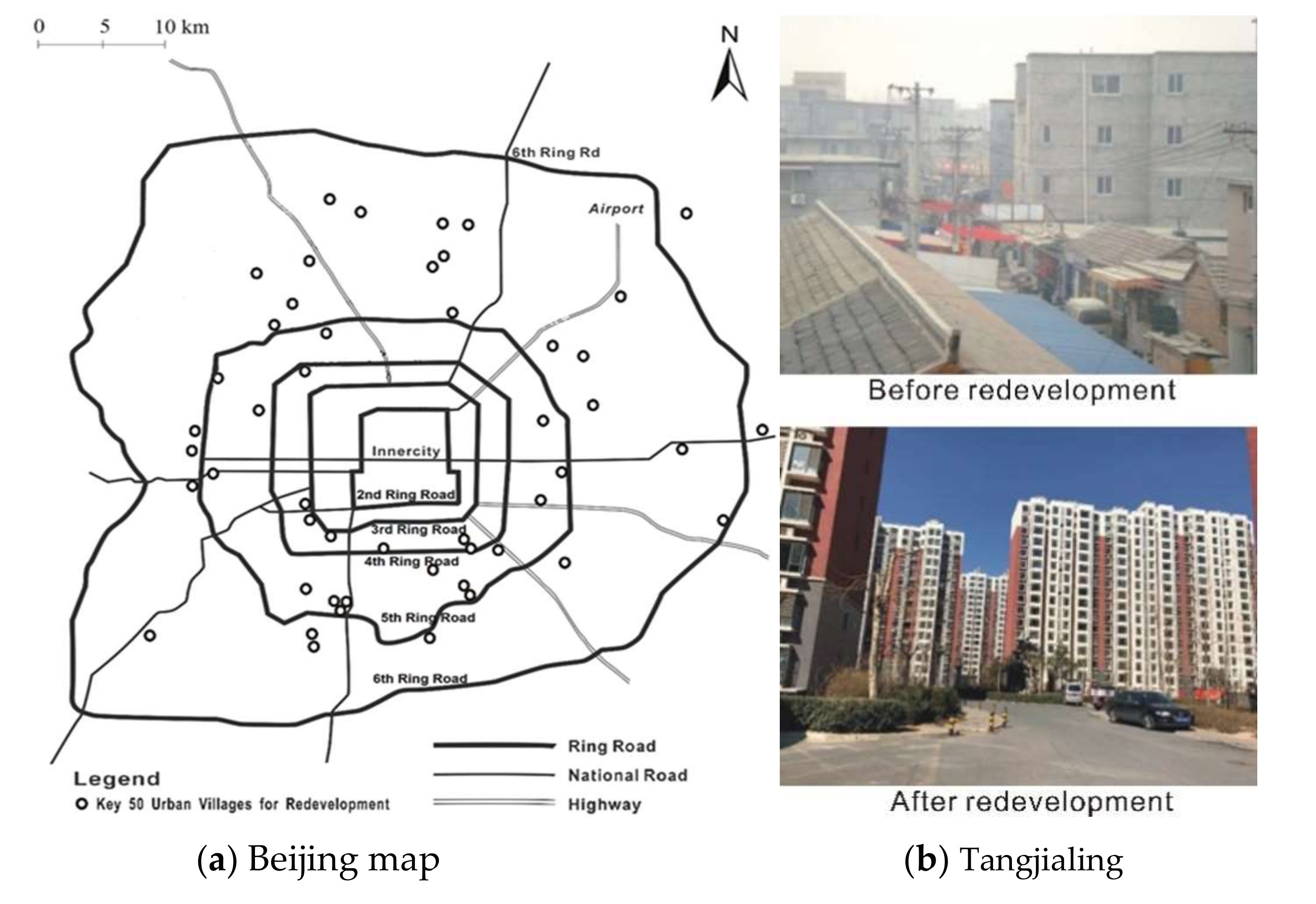

3.1. Research Area

3.2. Data and Methods

3.3. Results

4. Discussion: Revisiting a Synthesis between the Rural-Urban Dual System

4.1. Different Rural Land Institutions, Different Urbanization Paths in Developing Countries

4.2. Maintaining the Rural-Urban Dual System and Improving the Opportunity Structure for “Amphibious” Migrant Workers

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, R.; Wong, T. Urban village redevelopment in Beijing: The state-dominated formalization of informal housing. Cities 2018, 72, 160–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F. Housing in Chinese urban villages: The dwellers, conditions and tenancy informality. Hous. Stud. 2016, 31, 852–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, C. Urban village on a global scale: Diverse interpretations of one label. Urban Geogr. 2020, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.W.; Wei, Y. Two systems in one country: The origin, functions, and mechanisms of the rural-urban dual system in China. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 2019, 60, 422–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, Y. Land use change and driving factors in rural China during the period 1995–2015. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 105048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standing Committee. Land Administrative Law of the People’s Republic of China. The 9th National People’s Congress of the People’s Republic of China (1st Revision); Standing Committee: Beijing, China, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, C.C. Householding and split households: Examples and stories of Asian migrants to cities. Cities 2021, 113, 103147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, O.; Bloom, D.E. The new economics of labor migration. Am. Econ. Rev. 1985, 75, 173–178. [Google Scholar]

- Hugo, G.J. Effects of International Migration on the Family in Indonesia. Asian Pac. Migr. J. 2002, 11, 13–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M. Emigration and the Family Economy: Bangladeshi Labor Migration to Saudi Arabia. Asian Pac. Migr. J. 2011, 20, 389–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. Why Migrant Workers in China Continue to Build Large Houses in Home Villages: A Case Study of a Migrant-Sending Village in Anhui. Mod. China 2019, 46, 521–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Fan, C.C. China’s hukou puzzle: Why don’t rural migrants want urban hukou. China Rev. 2016, 16, 9–39. [Google Scholar]

- Han, J. Opinions on Promoting the Connection between Small Farmers and the Development of Modern Agriculture; Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs: Beijing, China, 2019. Available online: http://www.moa.gov.cn/hd/zbft_news/xnhxdnyfz/wzzb/ (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Aldous, T. Urban Villages: A Concept for Creating Mixed-Use Urban Developments on a Sustainable Scale; Urban Villages Group: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, H. The Urban. Revolution; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Liu, Y.; Chen, H. Growth of rural migrant enclaves in Guangzhou, China: Agency, everyday practice and social mobility. Urban Stud. 2015, 52, 3086–3105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L. Strangers in the City: Reconfigurations of Space, Power, and Social Networks Within China’s Floating Population; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, S.; Long, F.; Fan, C.C.; Gu, Y. Urban Villages in China: A 2008 Survey of Migrant Settlements in Beijing. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 2009, 50, 425–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Oostrum, M. Access, density and mix of informal settlement: Comparing urban villages in China and India. Cities 2021, 117, 103334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Wong, T.; Liu, S. The peri-urban mosaic of Changping in metropolizing Beijing: Peasants’ response and negotiation processes. Cities 2020, 107, 102932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Zhang, F.; Webster, C. Informality and the development and demolition of urban villages in the Chinese peri-urban area. Urban Stud. 2013, 50, 1919–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, K.; Chen, X. Land speculation by villagers: Territorialities of accumulation and exclusion in peri-urban China. Cities 2021, 119, 103394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiddle, G.L. Key theory and evolving debates in international housing policy: From legalisation to perceived security of tenure approaches. Geogr. Compass 2010, 4, 881–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhao, P. The determinants of informal housing price in Beijing: Village power, informal institutions, and property security. Cities 2018, 77, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Tong, D.; Wu, Y.; Li, G. Government-backed “laundering of the grey” in upgrading urban village properties: Ningmeng Apartment Project in Shuiwei Village, Shenzhen, China. Prog. Plann. 2021, 146, 100436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.C. Settlement intention and split households: Findings from a survey of migrants in Beijing’s urban villages. China Rev. 2011, 11, 11–42. [Google Scholar]

- News.Focus. Beijing Jinnian Dongqian Cunzhuang Chao 300 Ge, Yi Tengtui Tudi Yue 600 Gongqing [Beijing Dismantling 300 Villages for Redevelopment]. 2010. Available online: http://news.focus.cn/bj/2010-11-19/1105994.html (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Bao, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, X. Urban spectacles as a pretext: The hidden political economy in the 2010 Asian Games in Guangzhou, China. Urban Geogr. 2019, 40, 409–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.B. Contesting speculative urbanisation and strategising discontent. City 2014, 18, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shin, H.B.; Li, B. Whose games? The costs of being “Olympic citizens” in Beijing. Environ. Urban 2013, 25, 559–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ho, P.; Sun, L. A model for inclusive, pro-poor urbanization? The credibility of informal, affordable “single-family” homes in China. Cities 2021, 97, 102465. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, P. The “credibility thesis” and its application to property rights: (in)secure land tenure, conflict and social welfare in China. Land Use Policy 2014, 40, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, P. Unmaking China’s Development: Function and Credibility of Institutions; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Grabel, I. The political economy of “policy credibility”: The new-classical macroeconomics and the remaking of emerging economies. Camb. J. Econ. 2000, 24, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, R.; Wong, T.; Liu, S. Low-wage migrants in northwestern Beijing, China: The hikers in the urbanisation and growth process. Asia Pac. Viewp. 2013, 54, 352–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Wang, J. Gentrification effects of China’s urban village renewals. Urban Stud. 2017, 54, 214–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S. Loft-living under state-led financialisation: Adaptive reuse of industrial buildings for long-term rental apartments in Beijing, China. FinGeo Seminar, 2021/06/29. Available online: https://www.fingeo.net/ (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics; Pearson: New Jersey, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Haroldo, T.; Humberto, A.; De Oliveira, M.A. São Paulo peri-urban dynamics: Some social causes and environmental consequences. Environ. Urban 2007, 19, 207–223. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, K.W. Urbanization with Chinese Characteristics: The Hukou System and Migration; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- He, S.; Chang, Y. A zone of exception? Interrogating the hybrid housing regime and nested enclaves in China-Singapore Suzhou-Industrial-Park. Hous. Stud. 2020, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wily, L.A. Collective land ownership in the 21st Century: Overview of global trends. Land 2018, 7, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Home Owning | Subsidized Home Owning | Small Property-Owning | Renting | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban formal community | 13.3% | 0.6% | 0.1% | 86.0% | 100.0% |

| Urban village | 0.4% | 0.1% | 0.3% | 99.3% | 100.0% |

| Total | 6.9% | 0.3% | 0.2% | 92.6% | 100.0% |

| Migrants’ Choices Regarding the Informal Tenure of the Urban Village (Ref = Urban Formal Market) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | B | SE | Exp(β) |

| Household profile | |||

| Age | −0.054 *** | 0.006 | 0.947 |

| Gender (ref = female) | 0.108 | 0.096 | 1.114 |

| Marriage (ref = unmarried) | 0.448 *** | 0.165 | 1.565 |

| Education level (ref = college and above) | |||

| Primary and below | 0.460 ** | 0.217 | 1.583 |

| Junior secondary | 0.492 *** | 0.157 | 1.636 |

| Senior/technical secondary | 0.192 | 0.153 | 1.211 |

| Logged annual family income | −3.954 *** | 0.241 | 0.019 |

| Migration status | |||

| Household size in urban destinations | 0.021 | 0.050 | 1.021 |

| Place of origin (ref = East China) | |||

| North-eastern region | 0.531 *** | 0.193 | 1.701 |

| North-western region | 0.005 | 0.256 | 1.005 |

| North China | 0.188 | 0.118 | 1.207 |

| Central China | 0.182 | 0.125 | 1.200 |

| South China | −1.048 | 0.815 | 0.351 |

| South-western region | 0.389 * | 0.203 | 1.475 |

| Second generation of rural migrant workers (ref = others) | −0.192 * | 0.114 | 0.825 |

| Employment in urban destinations | |||

| Occupation (ref = blue collar) | |||

| Cadre, manager or head | 0.040 | 0.642 | 1.041 |

| Technician/professional | −0.099 | 0.215 | 0.906 |

| Staff/clerk | −0.665 | 0.421 | 0.514 |

| Service worker | −0.291 | 0.181 | 0.748 |

| Agricultural worker | 0.562 | 0.822 | 1.755 |

| Other | −0.829 *** | 0.281 | 0.437 |

| Industry (ref = labour-intensive manufacturing) | |||

| Primary industry | −0.364 | 0.742 | 0.695 |

| Non-manufacturing sectors in secondary industry | 0.118 | 0.223 | 1.125 |

| Capital-intensive manufacturing | 0.574 * | 0.329 | 1.775 |

| Skill-intensive manufacturing | 0.134 | 0.253 | 1.144 |

| Other types of manufacturing | 0.541 | 0.371 | 1.718 |

| Producer services | −0.047 | 0.199 | 0.954 |

| Public services | −0.599 ** | 0.245 | 0.550 |

| Consumer services | −0.086 | 0.163 | 0.918 |

| Employer type (ref = privately-owned/joint stock) | |||

| State-owned | −0.448 ** | 0.187 | 0.639 |

| Collective-owned | −0.253 | 0.381 | 0.776 |

| Foreign-invested/joint venture | −0.055 | 0.260 | 0.947 |

| Family- or individually-owned | −0.071 | 0.146 | 0.932 |

| Non-profit organization | −1.879 | 1.269 | 0.153 |

| Other | 0.596 *** | 0.196 | 1.814 |

| Employment status (ref = stable employees) | |||

| Temporary employees (no contract) | −0.059 | 0.205 | 0.942 |

| Employer | −0.656 *** | 0.238 | 0.519 |

| Self-running | 0.163 | 0.152 | 1.177 |

| Other | −0.296 | 0.389 | 0.744 |

| Housing pressure in urban destinations | |||

| Housing expense-to-income ratio | −5.795 *** | 0.408 | 0.003 |

| Landed status in rural origins | |||

| If still holding rural lands in hometown (ref = land loss) | |||

| Holding both farmland and homestead | 0.738 *** | 0.123 | 2.092 |

| Homestead only | 0.861 *** | 0.131 | 2.365 |

| Farmland only | 0.661 *** | 0.197 | 1.936 |

| Constant | 16.957 *** | 1.001 | |

| N | 2992 | ||

| df | 43 | ||

| λ2 | 1019.732 *** | ||

| −2 Log Likelihood | 3127.760 | ||

| Cox and Snell R2 | 0.289 | ||

| Nagelkerke R2 | 0.385 | ||

| Percent correctly classified | 74% | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, R.; Jia, Y. Resilience and Circularity: Revisiting the Role of Urban Village in Rural-Urban Migration in Beijing, China. Land 2021, 10, 1284. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10121284

Liu R, Jia Y. Resilience and Circularity: Revisiting the Role of Urban Village in Rural-Urban Migration in Beijing, China. Land. 2021; 10(12):1284. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10121284

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Ran, and Yuhang Jia. 2021. "Resilience and Circularity: Revisiting the Role of Urban Village in Rural-Urban Migration in Beijing, China" Land 10, no. 12: 1284. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10121284

APA StyleLiu, R., & Jia, Y. (2021). Resilience and Circularity: Revisiting the Role of Urban Village in Rural-Urban Migration in Beijing, China. Land, 10(12), 1284. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10121284