Sustainable Transformation of Resettled Communities for Landless Peasants: Generation Logic of Spatial Conflicts

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Grounded Theory

3.2. Selection of Case

3.3. Participants and Interviews

3.4. Development of Conceptual Model

3.4.1. Open Coding

3.4.2. Axial Coding

3.4.3. Selective Coding

3.4.4. Theoretical Saturation Test

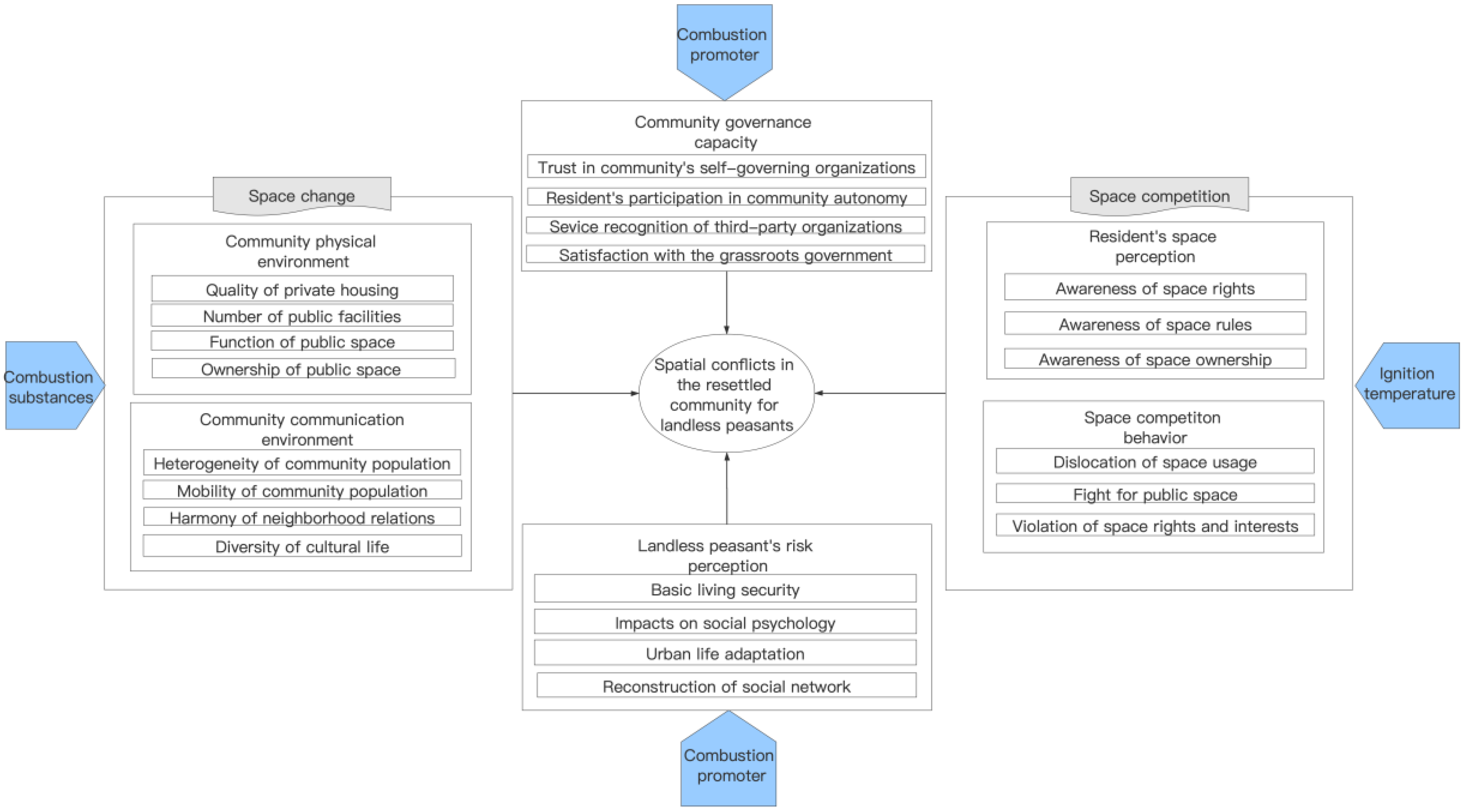

4. Generation Logic of Spatial Conflicts in Resettled Community

4.1. Space Change: Combustion Substance That Breeds Spatial Conflict

4.2. Landless Peasants’ Risk Perception: Combustion Promoter of Generation of Space Conflict

4.3. Community Governance Capacity: Combustion Promoter to Catalyze Spatial Conflict

4.4. Space Competition Fuse of Spatial Conflict

5. Governance Strategies of Spatial Conflict in Resettled Communities

5.1. Promote Gradual Transition of Community Space to Create High-Quality Community Environment

5.2. Improve Support Mechanism for Landless Peasants to Form Benign Psychological Perception

5.3. Explore New Community Governance Mechanisms to Enhance Community Governance Capabilities

5.4. Cultivate Residents’ Awareness of Community Rules and Reduce Space Competition Behaviors

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Poel, E.V.; O’Donnell, O.; Doorslaer, E.V. Is There a health penalty of China’s rapid urbanization? Health Econ. 2012, 21, 367–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Liu, Y.; Webster, C.; Wu, F. Property Rights Redistribution, Entitlement Failure and the Impoverishment of Landless Farmers in China. Urban Stud. 2009, 46, 1925–1949. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Q. Displaced villagers’ adaptation in concentrated resettlement community: A case study of Nanjing, China. Land Use Policy 2019, 88, 104097. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, W.; Zou, Y. Un-gating the gated community: The spatial restructuring of a resettlement neighborhood in Nanjing. Cities 2017, 62, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z. Beyond displacement-exploring the variegated social impacts of urban redevelopment. Urban Geogr. 2020, 41, 703–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, F.; Wuzhati, S.; Wen, B. Urban or village residents? A case study of the spontaneous space transformation of the forced upstairs farmers’ community in Beijing. Habitat Int. 2016, 56, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Ye, L.; Zhang, X. How community mobilization mediates conflict escalation? Evidence from three Chinese cities. J. Urban Aff. 2021, 43, 549–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, F.; Wu, F. Neighbourhood cohesion under the influx of migrants in Shanghai. Environ. Plan. A 2017, 49, 407–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcdonald, B.; Webber, M.; Duan, Y. Involuntary resettlement as an opportunity for development: The case of the urban resettlers of the Three Gorges Dam, China. J. Refug. Stud. 2008, 21, 82–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- de Sherbinin, A.; Castro, M.; Gemenne, F.; Cernea, M.M.; Adamo, S.; Fearnside, P.M.; Krieger, G.; Lahmani, S.; Oliver-Smith, A.; Pankhurst, A.; et al. Climate change. Preparing for resettlement associated with climate change. Science 2011, 334, 456–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oudshoorn, A.; Benbow, S.; Meyer, M. resettlement of Syrian refugees in Canada. J. Int. Migr. Integr. 2020, 21, 893–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebre, H.A. The impact of urban redevelopment-induced relocation on relocates’ livelihood asset and activity in Addis Ababa: The case of people relocated Arat Kilo Area. Asian J. Humanit. Soc. Stud. 2014, 2, 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Kate, A.; Verbitsky, J.; Wilson, K. In different voices: Auckland refugee communities’ engagement with conflict resolution in New Zealand. J. Int. Migr. Integr. 2019, 20, 459–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanclay, F. Project-Induced displacement and resettlement: From impoverishment risks to an opportunity for development? Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2017, 35, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Im, H.; Neff, J. Spiral loss of culture: Cultural trauma and bereavement of Bhutanese refugee elders. J. Immigr. Refug. Stud. 2021, 19, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, G.S. Conflict in the community: A theory of the effects of community size. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 1974, 68, 1245–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knox, J.B.; Coleman, J.S. Community conflict. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1958, 23, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soja, E.W. The Socio-Spatial Dialectic. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 1980, 70, 207–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knott, K. Spatial theory and the study of religion. Relig. Compass 2008, 2, 1102–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Źróbek-Różańska, A.; Zysk, E. Real estate as a subject of spatial conflict among Central and local authorities. Real Estate Manag. Valuat. 2015, 23, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chan, J.K.H. Conflict. Urban Ethics Anthr. 2018, 24, 73–97. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, X. Optimization analysis of right conflict in community sports development from the perspective of square dance. Bol. Tec. Tech. Bull. 2017, 55, 414–419. [Google Scholar]

- Ying, W. Governance strategies under spatial change: A study on the grass roots governance transformation of the “Village-Turned-Community”. Sociol. Stud. 2017, 6, 94–116. [Google Scholar]

- Sarrafi, M.; Moahmmadi, A. Involuntary resettlement: From a landslide-affected slum to a new neighbourhood. case study of Mina Resettlement Project; Ahvaz, Iran. J. Settl. Spat. Plan. 2018, 1, 11–24. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Liu, Z. A Theoretical explanation of resettlement community’s changing logic: Based on “System-Life” Analysis Frame. J. Nanjing Agric. Univ. 2016, 6, 34–40. [Google Scholar]

- Abrampah, D.A.M. Strangers on their own land: Examining community identity and social memory of relocated communities in the area of the Bui Dam in West-Central Ghana. Hum. Organ. 2017, 76, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Wu, X. Interpretation of the political sociology on the governance of the transitional community: From the perspective of social capital. J. Dalian Univ. Technol. 2012, 01, 101–105. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, C.; Pan, J.; Xia, M. Management of neighborhood avoidance conflict in “village to residence” community—taking ten general residential communities in Nantong, Jiangsu Province as an example. Jiang Hai Acad. 2014, 02, 201–208. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Wu, W.; Zhong, W.; Zeng, G.; Wang, S. The reshaping of social relations: Resettled rural residents in Zhenjiang, China. Cities 2017, 60, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daley, C. Exploring Community connections: Community cohesion and refugee integration at a local level. Commun. Dev. J. 2009, 44, 158–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendez, M.L.; Otero, G. Neighborhood conflicts, socio-spatial inequalities, and residential stigmatisation in Santiago, Chile. Cities 2017, 74, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakhmawati, W. Understanding classic, Straussian, and constructivist grounded theory approaches. Belitung Nurs. J. 2019, 5, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Kang, J. A grounded theory approach to the subjective understanding of urban soundscape in Sheffield. Cities 2016, 5, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhou, L.; Xiong, L. Evolution of the physical and social spaces of ‘village resettlement communities’ from the production of space perspective: A case study of Qunyi community in Kunshan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Drucker, S.J.; Gumpert, G.G. Public space and communication: The Zoning of public interaction. Commun. Theory 2010, 1, 294–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heger, I. More than “Peasants without Land”: Individualisation and identity formation of landless peasants in the process of China’s State-Led Rural Urbanisation. J. Curr. Chin. Aff. 2020, 49, 332–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yang, S. The regulation and improvement of suburban landless peasants’ community in the charge of the government. SHS Web Conf. 2014, 6, 02012. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Y.; He, J.; Han, H.; Zhang, W. Evaluating residents’ satisfaction with market-oriented urban village transformation: A case study of Yangji Village in Guangzhou, China. Cities 2019, 95, 102394.1–102394.12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, F. Sustainable Urban community development: A case study from the perspective of self-governance and public participation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 617. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Sun, X.; Sun, L.; Choguill, C. Optimizing the governance model of urban villages based on integration of inclusiveness and urban service boundary (USB): A Chinese case study. Cities 2020, 96, 102427.1–102427.12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haoyu, C. “Conflict” or “Cooperation”: A Study on The Spontaneous Order of Urban Public Space Development from The Perspective of Stakeholders. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 960, 042043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, F. Neighborhood conflicts in urban China: From consciousness of property rights to contentious actions. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 2015, 56, 285–307. [Google Scholar]

- Shui, W.; Bai, J.; Zhang, S.; Chen, Y. Analysis of the influencing factors on resettled farmer’s satisfaction under the policy of the balance between urban construction land increasing and rural construction land decreasing: A case study of China’s Xinjin County in Chengdu City. Sustainability 2014, 6, 8522–8535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tanulku, B. Gated communities: Ideal packages or processual spaces of conflict? Hous. Stud. 2013, 28, 937–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giddens, A. Runaway World; Profile Books: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, H. The Production of Space; Blackwell: Somerset County, NJ, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

| Serial Number | Category | Original Data (Initial Concept) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Quality of private housing | A06 1: Water leakage, sound insulation, wall peeling, and other quality problems are common in relocated houses. (Poor housing quality) A18 1: The space between buildings is not big enough. (The distance between buildings is small) A03 1: Different from the pursuit of quality in commercial housing, the construction of relocated houses is always of a low standard. (Housing construction just meets the minimum standards) |

| 2 | Heterogeneity of community population | A04 1: There are people from different places in our community, so there are great difficulties in its integration. (Complex population structure) A06 1: There is a great difference in living habits and values between tenants and landless peasants. (There is a big gap in the living habits of different groups) A11 1: Tenants have poor maintenance and a low sense of belonging to the community. (Tenants have a low sense of community responsibility) |

| 3 | Impacts on social psychology | A06 1: The most important thing is the accumulated grievances. We farmers have paid so much for the urbanization process in Hangzhou, but our living conditions are also poor. (Sense of resentment towards demolition and resettlement) A05 1: The commercial houses’ residents look down upon us, and our rich people also look down upon them. (Sense of alienation from urban residents) A12 1: It is impossible for us to feel comfortable when a big gap exists between our compensation for land acquisition and others’. (Sense of relative deprivation caused by resettlement policy) A17 1: Compared with other communities, the construction conditions of our community are far behind, which is really unfair. (Sense of unfairness caused by the gap in community construction) A24 1: We used to have land and houses where we were quite self-sufficient. However, now the whole lifestyle has been changed, and I am not used to it actually. (Sense of loss caused by the decline in life satisfaction) |

| 4 | Trust in community’s self-governing organizations | A19 1: When we encounter problems, we are accustomed to asking the neighborhood committee for help. (Habitual reliance on neighborhood committee) A09 1: If I go to the neighborhood committee to report a problem, tomorrow I will be punished in an underhanded manner. (High cost of safeguarding rights) A09 1: Community homeowner committees are useless. They are tied to a pair of trousers with the property management company. (Little truth in the community homeowner committee) A22 1: It is two community secretaries that lead to such a big gap between our two communities. A secretary drinks but the other diligently works for the welfare of residents. (Community cadres have charismatic authority) |

| 5 | Awareness of space rights | A15 1: I do not approve of burning spiritual money or stacking items in the corridor, because that is our shared space. (Perception of public space rights) A14 1: While some residents piled up sundries and made the corridor crowded, considering the relationship with neighbors, others would not stop them. (Claims of public space rights) |

| 6 | Violation of space rights and interests | A01 1: Square dancing activity at night will cause noise pollution for some old residents who want to sleep and the young who want to relax. (Square dancing activity violates residents’ right to rest) A02 1: There was a large-scale conflict in the Tianxian community before, which was caused by the lampblack of the restaurant. (Business operation violates residents’ environmental rights) A03 1: Residents need to wash clothes and dry them in the sun, leading to frequent contradictions of dripping water from upstairs to downstairs. (Sun-drying violates the lighting rights of other residents) A18 1: Go and see our septic tank. It is not merely the unpleasant smell, but accidents may happen. (NIMBY facilities violate residents’ environmental rights and safety rights) A23 1: The construction of surrounding subway stations caused the relocated house to sink. (The surrounding construction violates the residents’ right to live) |

| Main Category | Category | Category Connotation |

|---|---|---|

| Community physical environment | Quality of private housing | Quality problems of relocated houses, such as water leakage, sound insulation, and wall peeling |

| Number of public facilities | The number of infrastructure establishments in the community and support facilities around the community | |

| Function of public space | Whether the function of public space conforms to the planning and whether it meets the needs of residents | |

| Ownership of public space | Whether the ownership of rights of public space is clear or not | |

| Community communication environment | Heterogeneity of community population | Differences among community residents in terms of occupation, income, social status, living habits, etc. |

| Mobility of community population | The ratio of the floating population such as tenants to the residents of the whole community | |

| Harmony of neighborhood relations | The frequency and depth of interaction between community residents | |

| Diversity of cultural life | Diversity of cultural activities of community residents and openness of cultural activities places | |

| Landless peasants’ risk perception | Basic living security | Whether farmers can meet their basic living needs after losing their means of production |

| Impacts on social psychology | The negative emotions of the landless peasants caused by changes in community environment, such as the sense of relative deprivation, sense of unfairness | |

| Urban life adaptation | The adaptation of farmers to urban life and sense of identity | |

| Reconstruction of social network | Reconstruction of the relatively stable relationship system | |

| Community governance capacity | Trust in community’s self-governing organizations | The degree of trust of community residents in neighborhood committees and community homeowner committees |

| Resident’s participation in community autonomy | The frequency and depth of community residents’ participation in community public affairs | |

| Service recognition of third-party organizations | Satisfaction of community residents with the services of property management companies and developers | |

| Satisfaction with the grassroots government | Satisfaction of community residents with the governance efficiency of grassroots government | |

| Residents’ space perception | Awareness of space rights | Be aware of your own space rights, advocate and defend your rights within the scope of the law |

| Awareness of spatial rules | Respect, awe, and compliance with space rules | |

| Awareness of space ownership | To whom the residents think the space belongs | |

| Space competition behavior | Dislocation of space usage | The encroachment of private space on public space caused by individual activities |

| Fight for public space | Neighborhood committees, property management companies, residents, and other community actors compete for public space usage and interests | |

| Violation of space rights and interests | The use of space by individuals and organizations violates the space rights and interests of others |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, K.; Gao, H.; Bao, H.; Zhou, F.; Su, J. Sustainable Transformation of Resettled Communities for Landless Peasants: Generation Logic of Spatial Conflicts. Land 2021, 10, 1171. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10111171

Xu K, Gao H, Bao H, Zhou F, Su J. Sustainable Transformation of Resettled Communities for Landless Peasants: Generation Logic of Spatial Conflicts. Land. 2021; 10(11):1171. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10111171

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Kexi, Hui Gao, Haijun Bao, Fan Zhou, and Jieyu Su. 2021. "Sustainable Transformation of Resettled Communities for Landless Peasants: Generation Logic of Spatial Conflicts" Land 10, no. 11: 1171. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10111171

APA StyleXu, K., Gao, H., Bao, H., Zhou, F., & Su, J. (2021). Sustainable Transformation of Resettled Communities for Landless Peasants: Generation Logic of Spatial Conflicts. Land, 10(11), 1171. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10111171