Analyzing Residents’ Landscape Preferences after Changes of Landscape Characteristics: A Qualitative Perspective

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

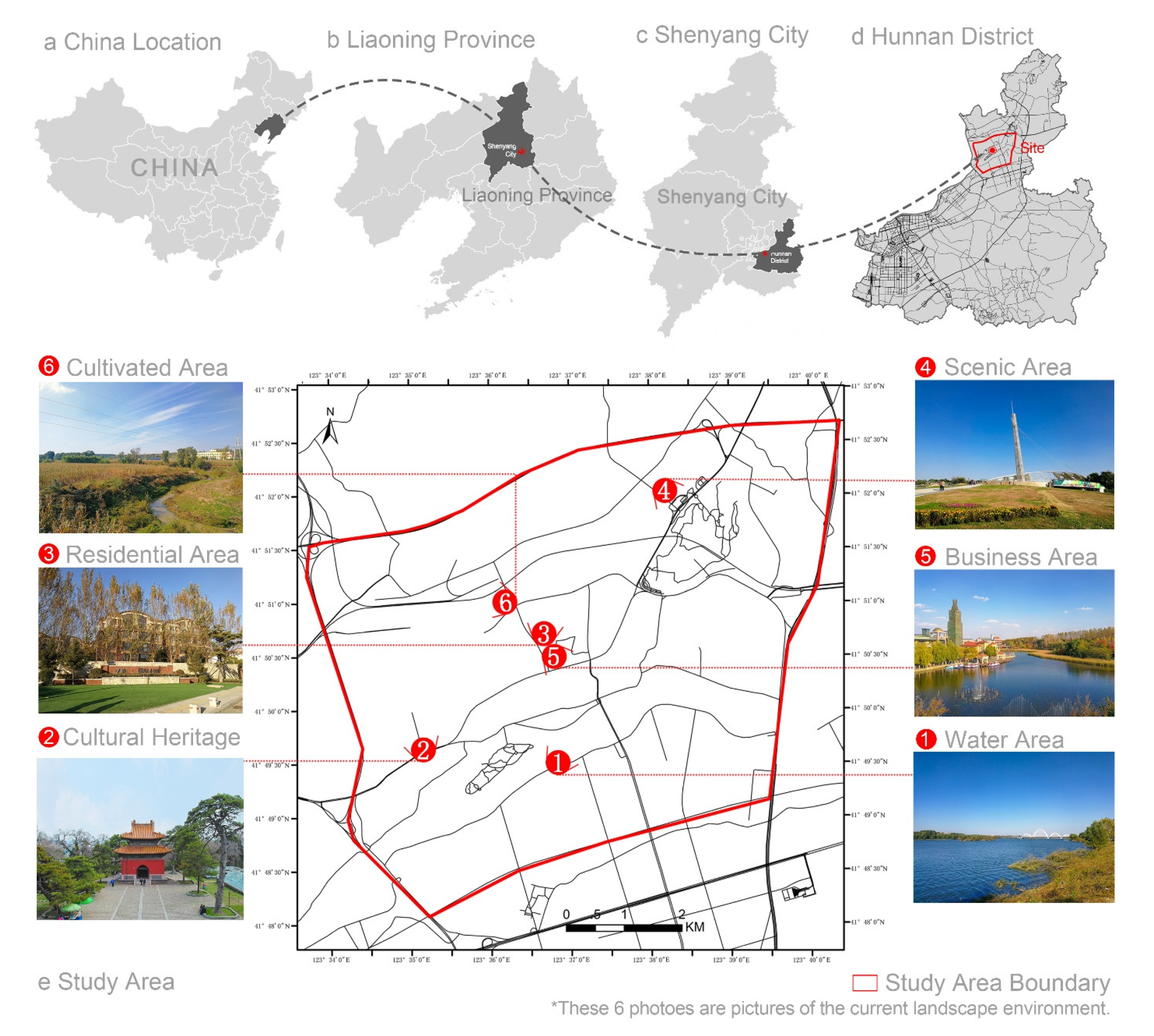

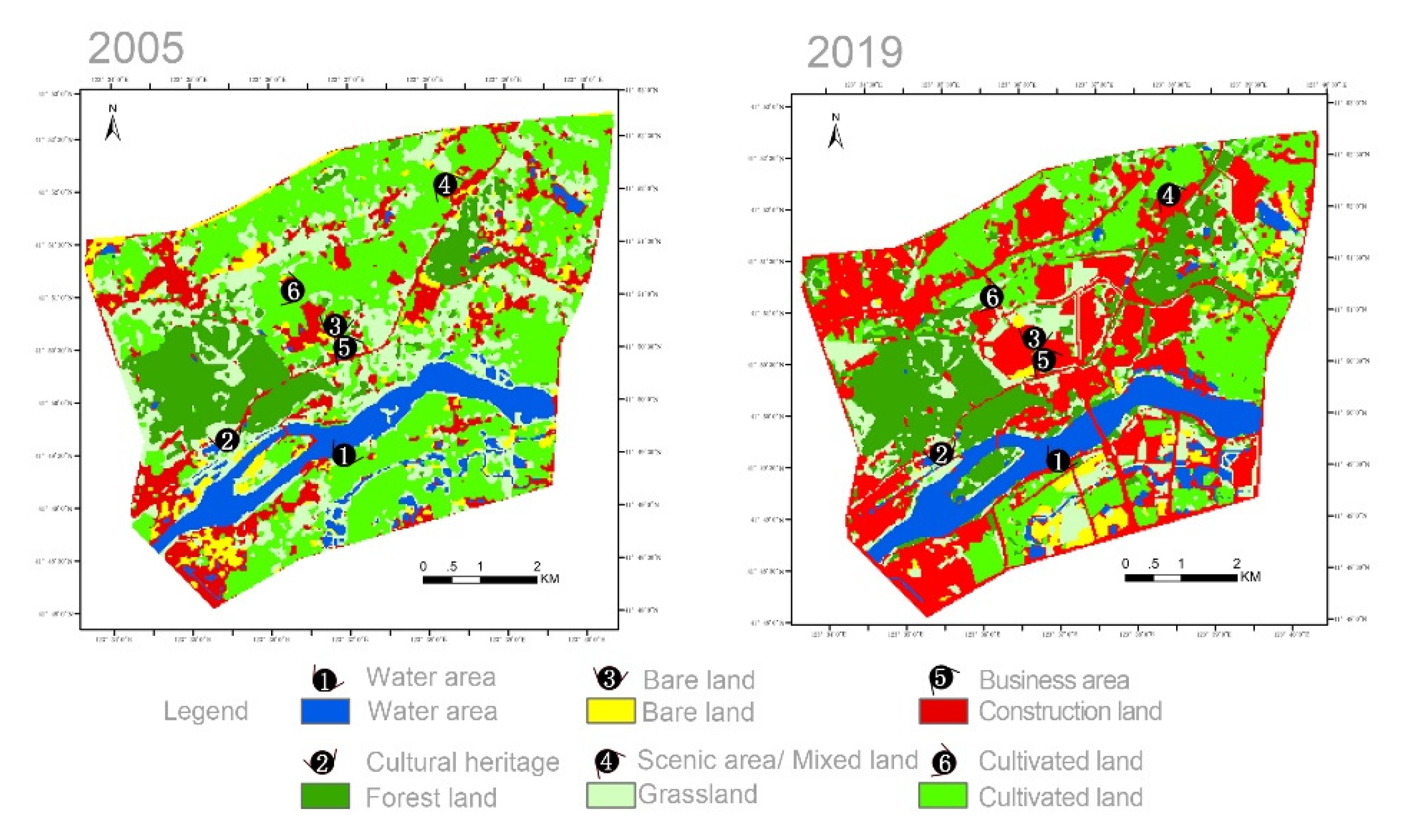

2.1. Study Site

2.2. Data Collection Source

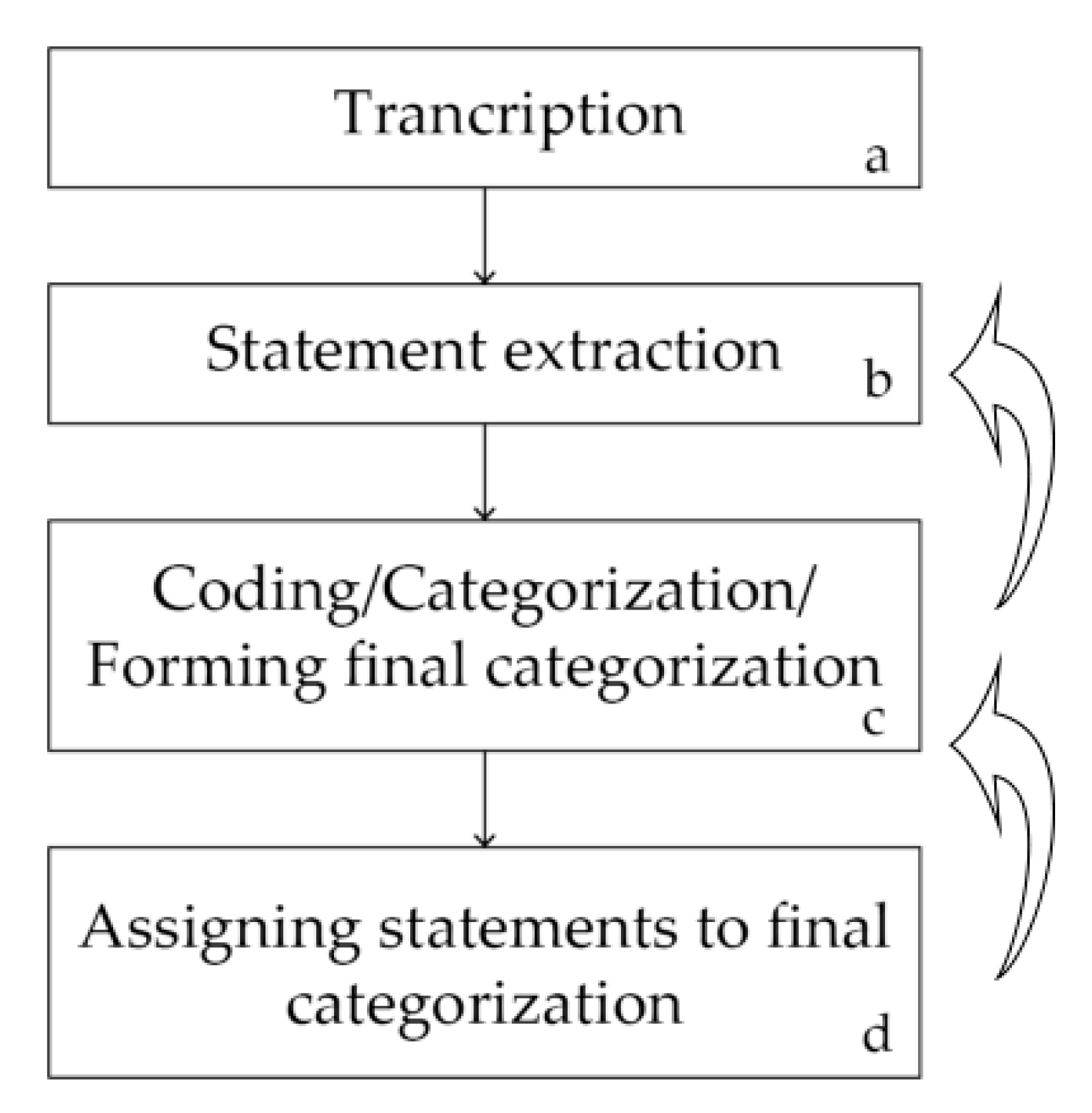

2.3. Content Analysis

2.4. Spatial Quantitative Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Description and Opinions of Landscape Ecological Changes

3.1.1. Water Area

3.1.2. Forest Land

3.1.3. Bare Land

3.1.4. Mixed Land

3.1.5. Construction Land

3.1.6. Cultivated Land

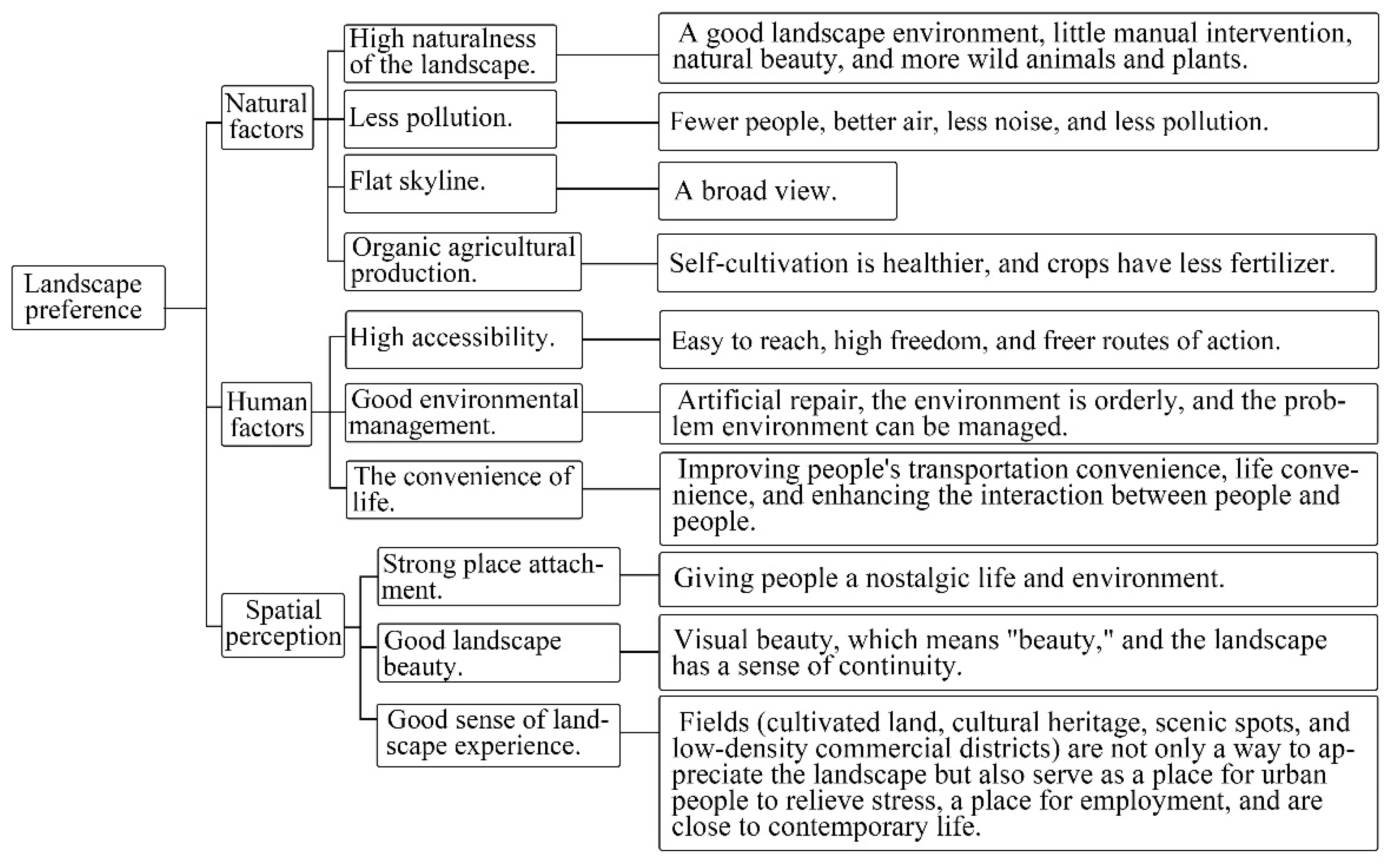

3.2. Reasons for Preferring Past and Current Landscape

3.2.1. Results of Discussions from the Perspective of Land Types

- Water Area

- There are three preference factors for the past water area. The first is that the landscape was highly natural, whereas today’s artificially carved landscapes seems unnatural. The second is that the skyline was flat with a broad horizon. The third is less pollution.

- There are three preference factors for the current water area. The first is environmental management, including artificial repairs and an orderly environment, such as planning parks to be cleaner and richer in vegetation types. The second is water area optimization: the water is not smelly, but the water is not clear. The third is that the convenience of life is better: transportation is improved, bridges have been built, and transportation is convenient. Moreover, the interaction is better and interpersonal communication is convenient.

- Forest Land

- The reasons for preferring the past environment can be divided into three dimensions. Accessibility was better, recreation was more accessible, easy to reach, and with no restraints. The landscape was more natural, and there were many wild animals. The landscape had a good sense of beauty and continuity.

- The reasons for preferring the current environment can be divided into two dimensions. Artificial repairs and an orderly environment such that vegetation is more regular and diverse, functional areas are reasonable, and the roads are tidy. The environment experience is enhanced, and it is a place for relaxation.

- Bare Land

- The reasons for preferring the past environment can be divided into three dimensions. The environment had less pollution, better air, and less noise. The skyline was flat, and viewpoints were broad. It was more natural with many wild animals and plants.

- Preference for the current environment is mainly based on environmental management, convenient lifestyle, clean environment, and supporting communities.

- Mixed Land

- There are three preference factors for the past environment. The landscape was more natural and there were few people. There was better accessibility, greater freedom, easy access, and freer routes for recreation. Organic agricultural production and self-cultivation was healthier, with less chemical fertilizers and pesticides.

- There are two preference factors for the current environment. The sense of environmental experience is enhanced, and the scenic area can be used as a place for decompression from employment in the city. There is environment management, artificial repairs, an orderly environment and regular vegetation of various types.

- Construction Land

- There are four preference factors for the past environment. The landscape had natural beauty with abundant vegetation and animal sounds. There was less pollution, fewer people, good air, and less noise. The skyline was flat, and the field of view was broad. There was a sense of attachment, resulting in a feeling of nostalgia.

- There are two preference factors for the current environment. Enhancement of a sense of environmental experience, more employment, and being closer to the lives of contemporary people. The landscape has beauty.

- Cultivated Land

3.2.2. Urban Fringe Interpretation of Landscape Preferences

- Natural factors

- Residents’ descriptions of high naturalness are divided into a good landscape environment, little artificial intervention, natural beauty, and more wild animals and plants. Perceived naturalness is based on the naturalness felt by the subject [49]. Hull et al. (2001) [50] indicated that perceived naturalness includes health and authenticity, among other factors, in which authenticity is described as not artificially arranged. Tveit et al. (2006) [34] revealed that the dimensions of perceived naturalness include integrity, wilderness, and naturalness, among other factors, in which integrity refers to the absence of perceived interference and damage, and naturalness refers to natural elements in the environment. Assessing the coding and interpreting the interview content, and making comparisons with existing research, the study found that the naturalness as a factor had reliability and validity.

- Residents believe that less pollution is defined as fewer people, better air, less noise, and less pollution. Words associated with less pollution in previous studies included disturbance [34,51] and serene [52]. The Landscape Institute and Institute of Environmental Management Assessment (2013) [51] defined the negative impact of landscape change disturbance as changes completely different from the original landform, scale, and pattern that permanently reduce past value characteristics. Grahn and Stigsdotter (2010) [52] defined serene as being in an undisturbed, quiet, and calm environment and found that serene was a key factor in humans’ preferred urban green spaces. In this study, due to the changes in the landscape spatial pattern, the past landscape’s integrity was fragmented, which created problems in the current environment and making the public feel that it is noisier and polluted.

- Residents think that a flat skyline provides a broad landscape view. Similar words are associated with the flat skyline in previous studies, such as prospect [31] and visual scale [34]. Appleton (1996) [31] believed that prospect related to a broad field of view, and that controlling this would enable people to discover danger in time. It was an instinctive and conscious response to the living environment. Tveit et al. (2006) [34] defined visual scale as visibility and openness, directly related to landscape preferences [53,54]. Therefore, the public’s preference is directly related to the skyline’s flatness, and it is also a human instinct to respond to a safe environment.

- Organic agricultural production is described as self-cultivation, which is healthier, and with less fertilizer use. Organic farming and production positively affect soil and ecological protection [55]. In the Dutch agricultural open space, the combination of production value and other “green” values has contributed to the success of farmland protection [56]. In this study, due to changes in the basic environment, the residents who originally had cultivated land lost their farming rights, and agricultural food safety was beyond their control.

- Human factors

- High accessibility is described as ease of reach, great freedom, and freer routes of action. Dalvi and Martin (1976) [57] and Song (1996) [58] believed that accessibility related to degree of easy access, specifically with respect to the distance between destinations and place of residences, the environment, and the temporal and spatial autonomy of people [59]. Accessibility is one of the essential indicators for the public in choosing an event venue. When the event venue is close to residences or has convenient transportation and can be easily reached, the venue will be readily selected as the event destination [60].

- Good environmental management is described as artificial repair, an orderly environment, and environmental problems can be managed. Tveit et al. (2006) [34] regarded management as a key element of visual landscape management and defined it as a sense of order. Active and meticulous management would encourage humans to care about the landscape. Similar words have been associated with management in previous studies, such as care [61] and careful management [62]. “Aesthetic of care” and “cues of care” are mowing, trimming vegetation, trees, flowers, and providing neat garden roads [61]. van-Mansvelt and Kuiper (1999) [62] believed that the land could be well maintained and taken care of by good maintenance of the farming elements in the landscape. In our study, environmental management results (artificial repair, orderly environment) are similar to those of previous research. However, the results cover more range than in previous research, such as adding environmental governance.

- Convenience of life is described as improving people’s transportation convenience, life convenience, and interpersonal interaction. Convenience of life refers to the convenience of residents’ daily use of public and service facilities. The public service facilities necessary for daily life were divided into two categories: daily shopping and dining facilities, in a previous study [63]. In this study, convenience of life extended to convenient transportation and interpersonal communication, which is the landscape that people prefer today.

- Spatial perception

- Strong place attachment is described as providing people with a nostalgic life and environment. Place attachment refers to the emotional bond between people and place [64] and connects with the local natural environment [65]. Gobster (1999) [66] extended the concept of landscape quality assessment to the link with personal emotions, including the environment and human-environmental experience, memories, and imagination. In previous studies, similar words related to this included a sense of place [9,22]. Sense of place postulates that human perception extends to the meaning of the landscape [22] and is shaped by forces of nature, humanity, and society. People experience the shape, line, color, and quality of landscapes through the five senses, eliciting imagination memories and thus creating unique feelings about their experienced landscape [9].

- Landscape beauty is described as visual beauty, which means that beauty and the landscape have a sense of continuity. The landscape’s beauty is an experience based on the visible and the form, all described by words such as “beautiful and attractive.” Tveit et al. (2006) [34] regarded coherence as a key factor of visual landscape management and defined it as a reflection of a scene’s unity. Kaplan and Kaplan (1989) [33] believed that a coherent landscape environment could help people understand the environment by providing a sense of order to guide the observer’s attention and use it as a landscape evaluation indicator [33,67]. At the same time, continuity also reflects the correspondence between land use and natural conditions in a region.

- A good sense of landscape experience considers that cultivated land, cultural heritage, scenic spots, and low-density commercial districts do not only provide a way to appreciate the landscape but also serve as places for urban people to relieve stress, provide places for employment, and are close to contemporary life. Grammatikopoulou et al. (2012) [68] pointed out that organic farming provides a new landscape appreciation, as in our results. Landscape experience involves people’s explorations, including internal operation, experience, and the results of external stimuli acting on people [69]. Cultivated land, cultural heritage, scenic spots, and low-density commercial districts can enhance landscape experience. Residents believe that such places can bring them a sense of relaxation, closer to their needs.

4. Discussion

4.1. Past Environment Research Methods

4.2. Landscape Preferences in Urban Fringe Areas

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Water area | Questions | ||

|

| ||

| Cultural heritage | |||

|

| ||

| Residential area | |||

|

| ||

| Scenic area | |||

|

| ||

| Business Area | |||

|

| ||

| Cultivated area | |||

|

| ||

| Basic information of the interviewee: | |||

| 1. Gender: Male/Female | 2. Age | 3. Profession | |

| 4. Are you a resident of this area or the surrounding area? Yes/No | |||

| 5. Length of residence: Less than 5 years, 6–10 years, 11–15 years, more than 15 years | |||

| Interview date: | |||

Appendix B

| Land Use | Dimension | Original Encoding | The Key of Interviewee’s Statement |

| Water area | Landscape elements | Water quality and quantity |

|

| Riverbed |

| ||

| Aquatic creatures |

| ||

| Riverbed vegetation |

| ||

| Spatial memory | Spatial memory |

| |

| Forest land | Landscape elements | Vegetation |

|

| Roads |

| ||

| Spatial memory | Spatial memory |

| |

| Bare land | Landscape elements | Land cover |

|

| Soil |

| ||

| Mixed land | Landscape elements | Land cover |

|

| Roads |

| ||

| Animals |

| ||

| Constr-uction land | Landscape elements | Land cover |

|

| Soil |

| ||

| Roads |

| ||

| Cultiva-ted land | Landscape elements | Land cover |

|

| Rivers |

| ||

| Spatial memory | Spatial memory |

|

Appendix C

| Land Use | Stage | Original Encoding | The Key Interviewee Statements |

| Water area | Past | Highly nature |

|

| Sky line |

| ||

| Less pollution |

| ||

| Current | Environment management |

| |

| Environment optimization |

| ||

| The convenience of life |

| ||

| |||

| Forest land | Past | High accessibility |

|

| Highly nature |

| ||

| A good sense of beauty and continuity |

| ||

| Current | Artificial repairs and an orderly environment |

| |

| Environment experience |

| ||

| Bare land | Past | Less pollution |

|

| Skyline flat |

| ||

| Naturalness highly |

| ||

| Current | Environment management |

| |

| Mixed land | Past | Naturalness highly |

|

| Better accessibility |

| ||

| Organic agricultural production |

| ||

| Current | Enhance environment experience |

| |

| Environment management |

| ||

| Const-ruction land | Past | Natural Beauty |

|

| Less pollution |

| ||

| Skyline flat |

| ||

| Place attachment |

| ||

| Current | Enhance environment experience |

| |

| Good sense of beauty |

| ||

| Cultiva-ted land | Current | Less pollution |

|

| Enhance environment experience |

| ||

| Naturalness highly |

| ||

| Organic agricultural production |

| ||

| Place attachment |

| ||

| Skyline flat |

|

References

- United Nations. 2014 Revision of the World Urbanization Prospects. 2014. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/publications/2014-revision-world-urbanization-prospects.html (accessed on 12 July 2021).

- Ning, F.E.; Ou, S.J.; Hsu, C.Y.; Chien, Y.C. Analysis of landscape spatial pattern changes in urban fringe area: A case study of Hunhe Niaodao Area in Shenyang City. Landsc. Ecol. Eng. 2021, 17, 411–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, F.K.; Chi, Y.R.; Lal, R. Spatiotemporal characteristics analysis of multifunctional cultivated land: A case-study in Shenyang, Northeast China. Land Degrad. Dev. 2020, 31, 1812–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Li, C.L.; Liu, M.; Hu, Y.M.; Xiu, C.L. Change of impervious surface area and its impacts on urban landscape: An example of Shenyang between 2010 and 2017. Ecosyst. Health Sustain. 2020, 6, 1767511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermes, J.; Van Berkel, D.; Burkhard, B.; Plieninger, T.; Fagerholm, N.; von Haaren, C.; Albert, C. Assessment and valuation of recreational ecosystem services of landscapes. Ecosyst. Serv. 2018, 31, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ridding, L.E.; Redhead, J.W.; Oliver, T.H.; Schmucki, R.; McGinlay, J.; Graves, A.R.; Morris, J.; Bradbury, R.B.; King, H.; Bullock, J.M. The importance of landscape characteristics for the delivery of cultural ecosystem services. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 206, 1145–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Plieninger, T.; Bieling, C.; Fagerholm, N.; Byg, A.; Hartel, T.; Hurley, P.; López-Santiago, C.A.; Nagabhatla, N.; Oteros-Rozas, E.; Raymond, C.M.; et al. The role of cultural ecosystem services in landscape management and planning. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2015, 14, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yang, G.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Søderkvist Kristensen, L. From preference to landscape sustainability: A bibliometric review of landscape preference research from 1968 to 2019. Ecosyst. Health Sustain. 2021, 7, 1948355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, L.D. Landscape diversity and conservation. Sci. Dev. 2009, 439, 22–29. [Google Scholar]

- Atik, M.; Bell, S.; Erdogan, R. Understanding Cultural Interfaces in the Landscape: A Case Study of Ancient Lycia in the Turkish Mediterranean. Landsc. Res. 2013, 38, 222–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Antrop, M. Reflecting upon 25 years of landscape ecology. Landsc. Ecol. 2007, 22, 1441–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, M.A.; Anderson, D.H. Getting From Sense of Place to Place-Based Management: An Interpretive Investigation of Place Meanings and Perceptions of Landscape Change. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2005, 18, 625–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, D.; Daniel, T.C. Foundations for an Ecological Aesthetic: Can Information Alter Landscape Preferences? Soc. Nat. Resour. 2007, 21, 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, J. The Cultural Values Model: An integrated approach to values in landscapes. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2008, 84, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wartmann, F.M.; Frick, J.; Kienast, F.; Hunziker, M. Factors influencing visual landscape quality perceived by the public. Results from a national survey. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 208, 104024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devine-Wright, P.; Batel, S. Explaining public preferences for high voltage pylon designs: An empirical study of perceived fit in a rural landscape. Land Use Policy 2013, 31, 640–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, T. Potential of small town residents’ participation in local urbanization process: A case study on the northern region of Fujian Province. City Plann. Rev. 2016, 40, 94–100. [Google Scholar]

- Gobster, P.H.; Nassauer, J.I.; Daniel, T.C.; Fry, G. The shared landscape: What does aesthetics have to do with ecology? Landsc. Ecol. 2007, 22, 959–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zube, E.H. Themes in Landscape Assessment Theory. Landsc. J. 1984, 3, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakin, S. There’s more to landscape than meets the eye: Towards inclusive landscape assessment in resource and environmental management. Can. Geogr.-Geogr. Can. 2003, 47, 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vouligny, É.; Domon, G.; Ruiz, J. An assessment of ordinary landscapes by an expert and by its residents: Landscape values in areas of intensive agricultural use. Land Use Policy 2009, 26, 890–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seamon, D. The phenomenological contribution to environmental psychology. J. Environ. Psychol. 1982, 2, 119–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.J. Comparing the Landscape Evaluation Results between Experiential Paradigm and Cognitive Paradigm in Sun Moon Lake National Scenic Area. Master’s Thesis, National Chung Hsing University, Taichung, Taiwan, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Loder, A. ‘There’s a meadow outside my workplace’: A phenomenological exploration of aesthetics and green roofs in Chicago and Toronto. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 126, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.H. On the Theory and Method of Landscape Narration. China Sci. Technol. Panor. Mag. 2011, 1, 347–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbrugge, L.; van den Born, R. The role of place attachment in public perceptions of a re-landscaping intervention in the river Waal (The Netherlands). Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 177, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Burley, D.; Jenkins, P.; Laska, S.; Davis, T. Place Attachment and Environmental Change in Coastal Louisiana. Organ. Environ. 2007, 20, 347–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, Y.Y.; Li, Y.H. Constructing Landscape Experience Model of Tourism Destination: A Case of Penghu Islands. J. Outdoor Recreat. Study 2017, 30, 63–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliva, R.; Hunziker, M. Beyond the visual dimension: Using ideal type narratives to analyse people’s assessments of landscape scenarios. Land Use Policy 2009, 26, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoderer, B.M.; Tasser, E.; Carver, S.; Tappeiner, U. An integrated method for the mapping of landscape preferences at the regional scale. Ecol. Indic. 2019, 106, 105430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleton, J. The Experience of Landscape; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, E.O. Biophilia; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective; Cambrige University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Tveit, M.; Ode, A.; Fry, G. Key concepts in a framework for analysing visual landscape character. Landsc. Res. 2006, 31, 229–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, M.R.; Askarinejad, A. Designer’s approach for scene selection in tests of preference and restoration along a continuum of natural to manmade environments. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Howley, P. Landscape aesthetics: Assessing the general publics’ preferences towards rural landscapes. Ecol. Econ. 2011, 72, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, M.; Banerji, S.; Mitra, D. Land-use–land-cover change detection and application of Markov model: A case study of Eastern part of Kolkata. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020, 22, 4341–4360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.; Ge, S.D.; Zhang, X.Y.; Kim, G.; Lei, Y.K.; Liu, Y. Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Green Infrastructure in an Agricultural Peri-Urban Area: A Case Study of Baisha District in Zhengzhou, China. Land 2021, 10, 801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodarzi, M.; Haghtalab, N.; Saeedi, I.; Moore, N.J. Structural and functional improvement of urban fringe areas: Toward achieving sustainable built–natural environment interactions. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020, 22, 6727–6754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Han, Y.L.; Pu, L.J.; Jiang, B.; Yuan, S.F.; Xu, Y. A Novel Model for Detecting Urban Fringe and Its Expanding Patterns: An Application in Harbin City, China. Land 2021, 10, 876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Liu, Q.; Blaschke, T.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Hu, Y.; Wang, M.; Xu, Z.; Wu, J. Integrating land development size, pattern, and density to identify urban-rural fringe in a metropolitan region. Landsc. Ecol. 2020, 35, 2045–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunziker, M. The spontaneous reafforestation in abandoned agricultural lands:perception and aesthetic assessment by locals and tourists. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1995, 31, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Home, R.; Bauer, N.; Hunziker, M. Cultural and Biological Determinants in the Evaluation of Urban Green Spaces. Environ. Behav. 2009, 42, 494–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazrafshan, M.; Tabrizi, A.M.; Bauer, N.; Kienast, F. Place attachment through interaction with urban parks: A cross-cultural study. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 61, 127103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.F.; Shannon, S.E. Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayring, P. Qualitative Content Analysis. Qual. Soc. Res. 2000, 1, 159–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meneghello, S. The tourism–landscape nexus: Assessment and insights from a bibliographic analysis. Land 2021, 10, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, T.; Li, C.; Luo, Y.J. Changes in landscape pattern of built-up land and its driving factors during urban sprawl. ACta Ecol. Sin. 2020, 40, 3283–3294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.Z.; Chun, Y.C.; Chen, J.Z. Quantification of Perceived Naturalness Using Scene Gist Algorithm. J. Landsc. 2012, 18, 23–38. [Google Scholar]

- Hull, R.B.; Robertson, D.P.; Kendra, A. Public understandings of nature: A case study of local knowledge about “natural” forest conditions. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2001, 14, 325–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landscape Institute; Institute of Environmental Management Assessment. Guidelines for Landscape and Visual Impact Assessment; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Grahn, P.; Stigsdotter, U.K. The relation between perceived sensory dimensions of urban green space and stress restoration. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2010, 94, 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clay, G.R.; Smidt, R.K. Assessing the validity and reliability of descriptor variables used in scenic highway analysis. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2004, 66, 239–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanyu, K. Visual properties and affective appraisals in residential areas in daylight. J. Environ. Psychol. 2000, 20, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahat, M.M.; Alananbeh, K.M.; Othman, Y.A.; Leskovar, D.I. Soil Health and Sustainable Agriculture. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ives, C.D.; Kendal, D. Values and attitudes of the urban public towards peri-urban agricultural land. Land Use Policy 2013, 34, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalvi, M.Q.; Martin, K.M. The measurement of accessibility: Some preliminary results. Transportation 1976, 5, 17–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.F. Some tests of alternative accessibility measures: A population density approach. Land Econ. 1996, 72, 474–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, H.J. Modeling accessibility using space-time prism concepts within geographiacl information-systems. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Syst. 1991, 5, 287–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.X.; Sun, J.Y. Antecedents and Consequences of Place Attachment. J. Geogr. Sci. 2009, 55, 43–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassauer, J.I. Cultural sustainability: Aligning aesthetics and ecology. In Placing Nature: Culture and Landscape Ecology; Nassauer, J.I., Ed.; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1997; pp. 67–83. [Google Scholar]

- van-Mansvelt, J.D.; Kuiper, J. Criteria for the humanity realm: Psychology and physiognomy and cultural heritage. Checkl. Sustain. Landsc. Manag. 1999, 116–134. [Google Scholar]

- Ying, L.; Niu, W. Evaluation of Resident Living Convenience in the Main Urban Area of Wuhan Based on POI Data. Territ. Nat. Resour. Study 2020, 3, 14–17. [Google Scholar]

- Altman, I.; Low, S.M. Place Attachment; Plenum Publishing Corporatiom: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Raymond, C.M.; Brown, G.; Weber, D. The measurement of place attachment Personal, community, and environmental connections. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 422–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobster, P.H. An Ecological Aesthetic for Forest Landscape Management. Landsc. J. 1999, 18, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, S. Landscape: Pattern, Perception, and Process; E & FN Spon: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Grammatikopoulou, I.; Pouta, E.; Salmiovirta, M.; Soini, K. Heterogeneous preferences for agricultural landscape improvements in southern Finland. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2012, 107, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, M.H. The Production of Mindscapes: A Comprehensive Theory of Landscape Experience. Doctor Dissertation, Wageningen University, Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Berto, R. The role of nature in coping with psycho-physiological stress: A literature review on restorativeness. Behav. Sci. 2014, 4, 394–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Korpela, K.M.; Hartig, T.; Kaiser, F.G.; Fuhrer, U. Restorative Experience and Self-Regulation in Favorite Places. Environ. Behav. 2001, 33, 572–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Born, R.J.G.; Verbrugge, L.N.H.; Ganzevoort, W. Assessing stakeholder perceptions of landscape and place in the context of a major river intervention: A call for their inclusion in adaptive management. Water Policy 2019, 22, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Năstase, I.I.; Pătru-Stupariu, I.; Kienast, F. Landscape Preferences and Distance Decay Analysis for Mapping the Recreational Potential of an Urban Area. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maas, J.; Verheij, R.A.; Groenewegen, P.P.; de Vries, S.; Spreeuwenberg, P. Green space, urbanity, and health: How strong is the relation? J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2006, 60, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lee, A.C.K.; Maheswaran, R. The health benefits of urban green spaces: A review of the evidence. J. Public Health 2011, 33, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Japelj, A.; Mavsar, R.; Hodges, D.; Kovač, M.; Juvančič, L. Latent preferences of residents regarding an urban forest recreation setting in Ljubljana, Slovenia. Forest Policy Econ. 2016, 71, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polat, A.T.; Akay, A. Relationships between the visual preferences of urban recreation area users and various landscape design elements. Urban For. Urban Green. 2015, 14, 573–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hami, A.; Tarashkar, M. Assessment of women’s familiarity perceptions and preferences in terms of plants origins in the urban parks of Tabriz, Iran. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 32, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Time | 2005 | 2019 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Area (ha) | Percentage (%) | Area (ha) | Percentage (%) |

| Water area | 476.64 | 8.89% | 540.36 | 10.08% |

| LSI | AI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 2019 | 2005 | 2019 | |

| Water area | 9.92 | 8.63 | 87.53 | 90.03 |

| Time | 2005 | 2019 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Area (ha) | Percentage (%) | Area (ha) | Percentage (%) |

| Cultivated land | 2028.69 | 37.84 | 1118.61 | 20.86 |

| LSI | AI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 2019 | 2005 | 2019 | |

| Cultivated land | 17.77 | 17.31 | 88.73 | 85.24 |

| Past | Current | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Code | Number of Photos | Code | Number of Photos | Code | Number of Photos |

| High naturalness | All | Organic agricultural production | 4.6 | Good environmental management | 1.2.3.4 |

| Less pollution | 1.3.4.5 | Strong place attachment | 5.6 | Good sense of landscape experience | 2.4.5 |

| Flat skyline | 1.2.5.6 | Good landscape beauty | 2 | The convenience of life | 1.2.3 |

| High accessibility | 2.4 | Good sense of landscape experience | 6 | Good landscape beauty | 5 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ning, F.; Ou, S.-J. Analyzing Residents’ Landscape Preferences after Changes of Landscape Characteristics: A Qualitative Perspective. Land 2021, 10, 1128. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10111128

Ning F, Ou S-J. Analyzing Residents’ Landscape Preferences after Changes of Landscape Characteristics: A Qualitative Perspective. Land. 2021; 10(11):1128. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10111128

Chicago/Turabian StyleNing, Fuer, and Sheng-Jung Ou. 2021. "Analyzing Residents’ Landscape Preferences after Changes of Landscape Characteristics: A Qualitative Perspective" Land 10, no. 11: 1128. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10111128

APA StyleNing, F., & Ou, S.-J. (2021). Analyzing Residents’ Landscape Preferences after Changes of Landscape Characteristics: A Qualitative Perspective. Land, 10(11), 1128. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10111128