Mean Normalized Force Computation for Different Types of Obstacles due to Dam Break Using Statistical Techniques

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Experiments

, with Fx being force in the x-direction, ρ being density of the water during runs as 998 kg/m3, h being the bore height, b being width of the object perpendicular to the flow, and finally u being the flow velocity. In this study the mean normalized force,

, with Fx being force in the x-direction, ρ being density of the water during runs as 998 kg/m3, h being the bore height, b being width of the object perpendicular to the flow, and finally u being the flow velocity. In this study the mean normalized force,  is timely averaged within interval t1–t2 as [Equation (10)]:

is timely averaged within interval t1–t2 as [Equation (10)]:

| h1 | Large | Medium | Small | Rectangular | Diamond |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D = 140mm | D = 60.6mm | D = 29mm | SC = 120 mm × 120 mm | SC = 120 mm × 120 mm | |

|  |  |  |  | |

| 100 mm | + | + | + | + | + |

| 125 mm | + | x | x | + | + |

| 150 mm | + | + | x | + | + |

| 175 mm | x | x | x | + | + |

| 200 mm | + | + | + | + | + |

| 225 mm | + | x | x | + | + |

| 250 mm | + | + | + | + | + |

| 275 mm | + | x | x | + | + |

| 300 mm | + | + | + | + | + |

4. The Statistical Analysis

and other nondimensional parameters as Reh, Reb, Fr, h/b, in which Reh =

and other nondimensional parameters as Reh, Reb, Fr, h/b, in which Reh =  is the flow Reynolds number, Reb =

is the flow Reynolds number, Reb =  is the object Reynolds number, with

is the object Reynolds number, with  being kinematic viscosity and u the flow velocity. Fr =

being kinematic viscosity and u the flow velocity. Fr =  is the Froude number, in which h is the bore height.

is the Froude number, in which h is the bore height.4.1. Basic Statistics and Simple Correlation Analysis

in order to summarize the characteristics of a data set.

in order to summarize the characteristics of a data set.  | Reb (×105) | Reh (×104) | h/b | Fr | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min. | 0.89 | 0.17 | 2.28 | 0.29 | 0.86 |

| Max. | 2.26 | 2.19 | 12.77 | 3.42 | 1.31 |

| Mean | 1.74 | 1.14 | 7.32 | 0.87 | 1.13 |

| St. Dev. | 0.42 | 0.55 | 3.56 | 0.73 | 0.15 |

and its components are calculated in Table 3. The correlation matrix is useful for checking the pattern of relationship between pairs. It must be noted that correlation coefficient does neither identify causality nor measure nonlinear association, but only linear association. Therefore, correlation analysis is performed to select statistically significant variables that have strong relationship with

and its components are calculated in Table 3. The correlation matrix is useful for checking the pattern of relationship between pairs. It must be noted that correlation coefficient does neither identify causality nor measure nonlinear association, but only linear association. Therefore, correlation analysis is performed to select statistically significant variables that have strong relationship with  , considering only the linear relationship. In correlation analysis, the values close to “1” mean there is a strong relationship, whereas “0” indicates that the two variables are independent of each other. It is demonstrated in Table 3 that

, considering only the linear relationship. In correlation analysis, the values close to “1” mean there is a strong relationship, whereas “0” indicates that the two variables are independent of each other. It is demonstrated in Table 3 that  is highly correlated with h/b, Reh, Fr, whereas lowly with Reb. The most linearly correlated parameter to

is highly correlated with h/b, Reh, Fr, whereas lowly with Reb. The most linearly correlated parameter to  is h/b. It should be taken into account, unfortunately, that variables except h/b, are correlated with each other in a medium level, which may cause collinearity problem in regression analysis.

is h/b. It should be taken into account, unfortunately, that variables except h/b, are correlated with each other in a medium level, which may cause collinearity problem in regression analysis.| Cr | Reb | h/b | Reh | Fr | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cr | 1.000 | 0.239 | −0.767 | −0.500 | −0.472 |

| Reb | 0.239 | 1.000 | −0.548 | 0.480 | 0.511 |

| h/b | −0.767 | −0.548 | 1.000 | 0.376 | 0.339 |

| Reh | −0.500 | 0.480 | 0.376 | 1.000 | 0.960 |

| Fr | −0.472 | 0.511 | 0.339 | 0.960 | 1.000 |

4.2. Multiple Linear Regression Model

is the dependent variable whereas Fr, Reh, Reb and h/b variables are independent. The R2 of linear regression model is 0.642 while adjusted R2 is 0.595. Usually, the more predictors included, the higher R2 is obtained. Hence, adjusted R2 is suggested for model complexity to provide a more fair comparison of model performance. The adjusted R2 is calculated as [Equation (12)]:

is the dependent variable whereas Fr, Reh, Reb and h/b variables are independent. The R2 of linear regression model is 0.642 while adjusted R2 is 0.595. Usually, the more predictors included, the higher R2 is obtained. Hence, adjusted R2 is suggested for model complexity to provide a more fair comparison of model performance. The adjusted R2 is calculated as [Equation (12)]:

| Model | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | Significance | Correlations | Collinearity Statistics | Collinearity Diagnostics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. Error | Beta | Zero-order | Partial | Part | Tolerance | VIF | Eigen value | Condition Index | |||

| Constant | 2.48 | 0.93 | – | 2.67 | 0.01 | – | – | – | – | – | 4.41 | 1.00 |

| Reb | −0.06 | 0.23 | −0.07 | −0.25 | 0.80 | 0.24 | −0.05 | −0.03 | 0.14 | 7.24 | 0.47 | 3.07 |

| Reh | −0.02 | 0.05 | −0.13 | −0.32 | 0.75 | −0.50 | −0.06 | −0.03 | 0.07 | 14.62 | 0.11 | 6.40 |

| h/b | −0.43 | 0.16 | −0.74 | −2.70 | 0.01 | −0.77 | −0.44 | −0.30 | 0.16 | 6.26 | 0.01 | 18.77 |

| Fr | −0.16 | 1.14 | −0.06 | −0.14 | 0.89 | −0.47 | −0.03 | −0.02 | 0.07 | 14.14 | 0.00 | 75.14 |

are explained by Reb, Fr and Reb together. The second part of Table 4 is reserved to most known collinearity statistics and diagnostics. The tolerance is the percentage of the variance in a given predictor that cannot be explained by the other predictors. Thus, the small tolerances show that a high proportion of the variance in a given predictor can be explained by the other predictors. When the tolerances are close by “0” as an indication of high multicollinearity then standard error of the regression coefficients will be inflated. By definition, variance inflation factors (VIF) are inversely related to the tolerances. A VIF that is greater than 2 is usually considered problematic. The smallest VIF in the Table 4 is 6.264 for h/b. Other collinearity diagnostics, condition indexes, confirm that there are serious problems with multicollinearity. The condition indices are computed as the square roots of the ratios of the largest eigenvalue to each successive eigenvalue. The values of condition indices that are greater than 15 indicate a possible problem with collinearity while greater than 30 is a serious problem. One of the condition indices is larger than 30, suggesting a very serious problem with collinearity. Although a serious multicollinearity problem exists, the linear model indicates that the most predictive variable is h/b.

are explained by Reb, Fr and Reb together. The second part of Table 4 is reserved to most known collinearity statistics and diagnostics. The tolerance is the percentage of the variance in a given predictor that cannot be explained by the other predictors. Thus, the small tolerances show that a high proportion of the variance in a given predictor can be explained by the other predictors. When the tolerances are close by “0” as an indication of high multicollinearity then standard error of the regression coefficients will be inflated. By definition, variance inflation factors (VIF) are inversely related to the tolerances. A VIF that is greater than 2 is usually considered problematic. The smallest VIF in the Table 4 is 6.264 for h/b. Other collinearity diagnostics, condition indexes, confirm that there are serious problems with multicollinearity. The condition indices are computed as the square roots of the ratios of the largest eigenvalue to each successive eigenvalue. The values of condition indices that are greater than 15 indicate a possible problem with collinearity while greater than 30 is a serious problem. One of the condition indices is larger than 30, suggesting a very serious problem with collinearity. Although a serious multicollinearity problem exists, the linear model indicates that the most predictive variable is h/b. 4.3. Stepwise Multiple Linear Regression Model

and four independent variables were used to construct the stepwise model. The regression statistics of final step are gathered in Table 5. Tolerance, VIF and condition index values show that the regression model is not ill from collinearity. Stepwise model is consisted of two steps and only two variables, h/b and Reh, are included in the final regression step, as these variables are found significant in regression. Reb and Fr are found to be insignificant to predict

and four independent variables were used to construct the stepwise model. The regression statistics of final step are gathered in Table 5. Tolerance, VIF and condition index values show that the regression model is not ill from collinearity. Stepwise model is consisted of two steps and only two variables, h/b and Reh, are included in the final regression step, as these variables are found significant in regression. Reb and Fr are found to be insignificant to predict  , so these variables are not included in regression. The R2 change is only 0.052 when Reh is entered in model in the second step. As seen from R2 change, the contribution of Reh is very limited when compared to h/b to regress the

, so these variables are not included in regression. The R2 change is only 0.052 when Reh is entered in model in the second step. As seen from R2 change, the contribution of Reh is very limited when compared to h/b to regress the  . The ratio of the absolute values of standardized coefficients show that h/b is about three times more important than Reh (have more contribution rate in the prediction) to regress

. The ratio of the absolute values of standardized coefficients show that h/b is about three times more important than Reh (have more contribution rate in the prediction) to regress  .

.| Model | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | Significance | Correlations | Collinearity Statistics | Collinearity Diagnostics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. Error | Beta | Zero-order | Partial | Part | Tolerance | VIF | Eigen value | Cond. Index | |||

| Constant | 2.30 | 0.10 | – | 22.06 | 0.00 | – | – | – | – | 2.65 | 1.00 | |

| h/b | −0.39 | 0.07 | −0.67 | −5.90 | 0.00 | −0.77 | −0.72 | −0.63 | 0.86 | 1.16 | 0.25 | 3.23 |

| Reh | −0.03 | 0.01 | −0.25 | −2.15 | 0.04 | −0.50 | −0.36 | −0.23 | 0.86 | 1.16 | 0.10 | 5.23 |

4.4. Principal Component Analysis

- Keeping factors which have an eigenvalue greater than “1” (Guttman-Kaiser rule);

- Retaining the factors which, in total, account for about 70%–80% of the variance;

- Obtaining factors before the breaking point or elbow of trend in a scree-plots.

| Component | Initial Eigenvalues | Extraction Sums of Squared Loadings | Rotation Sums of Squared Loadings | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | % of Variance | Cumulative % | Total | % of Variance | Cumulative % | Total | % of Variance | Cumulative % | |

| 1 | 1.571 | 52.354 | 52.354 | 1.571 | 52.354 | 52.354 | 1.528 | 50.923 | 50.923 |

| 2 | 1.369 | 45.644 | 97.998 | 1.369 | 45.644 | 97.998 | 1.412 | 47.075 | 97.998 |

| 3 | 0.060 | 2.002 | 100.000 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Component | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | |

| Reb | −0.791 | 0.594 |

| h/b | 0.944 | 0.298 |

| Reh | 0.107 | 0.985 |

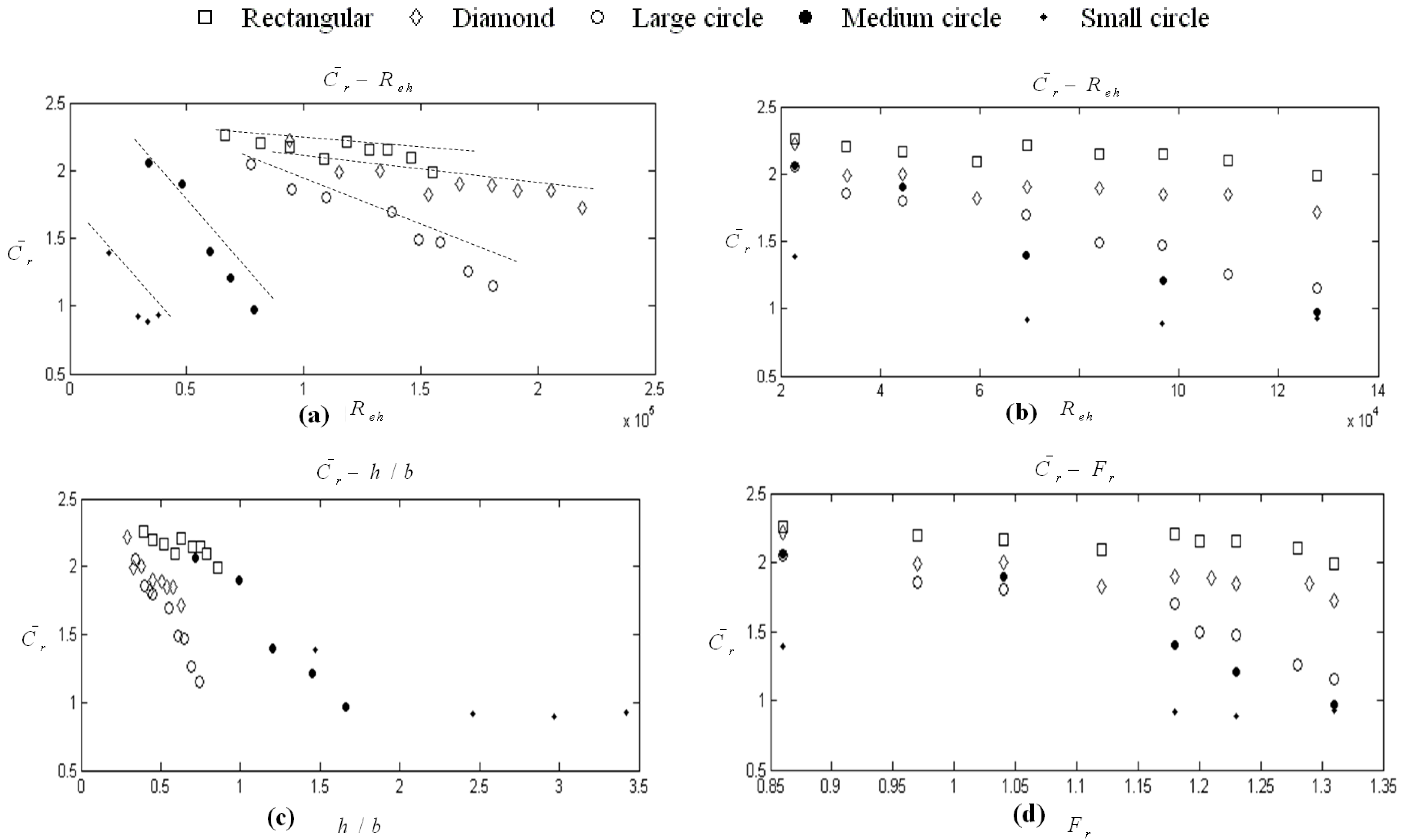

4.5. Cluster Analysis

. The linkage method defines how the distance between two clusters is measured. Nearest neighbor, furthest neighbor, Centroid clustering, Median clustering, and Ward’s method are among those widely used. In this research, Ward’s method is applied. The main idea behind Ward’s method is that the linkage function specifying the distance between two clusters is computed as the increase in the “error sum of squares” (ESS) after fusing two clusters into a single cluster. Ward’s method seeks to choose the successive clustering steps so as to minimize the increase in ESS at each step.

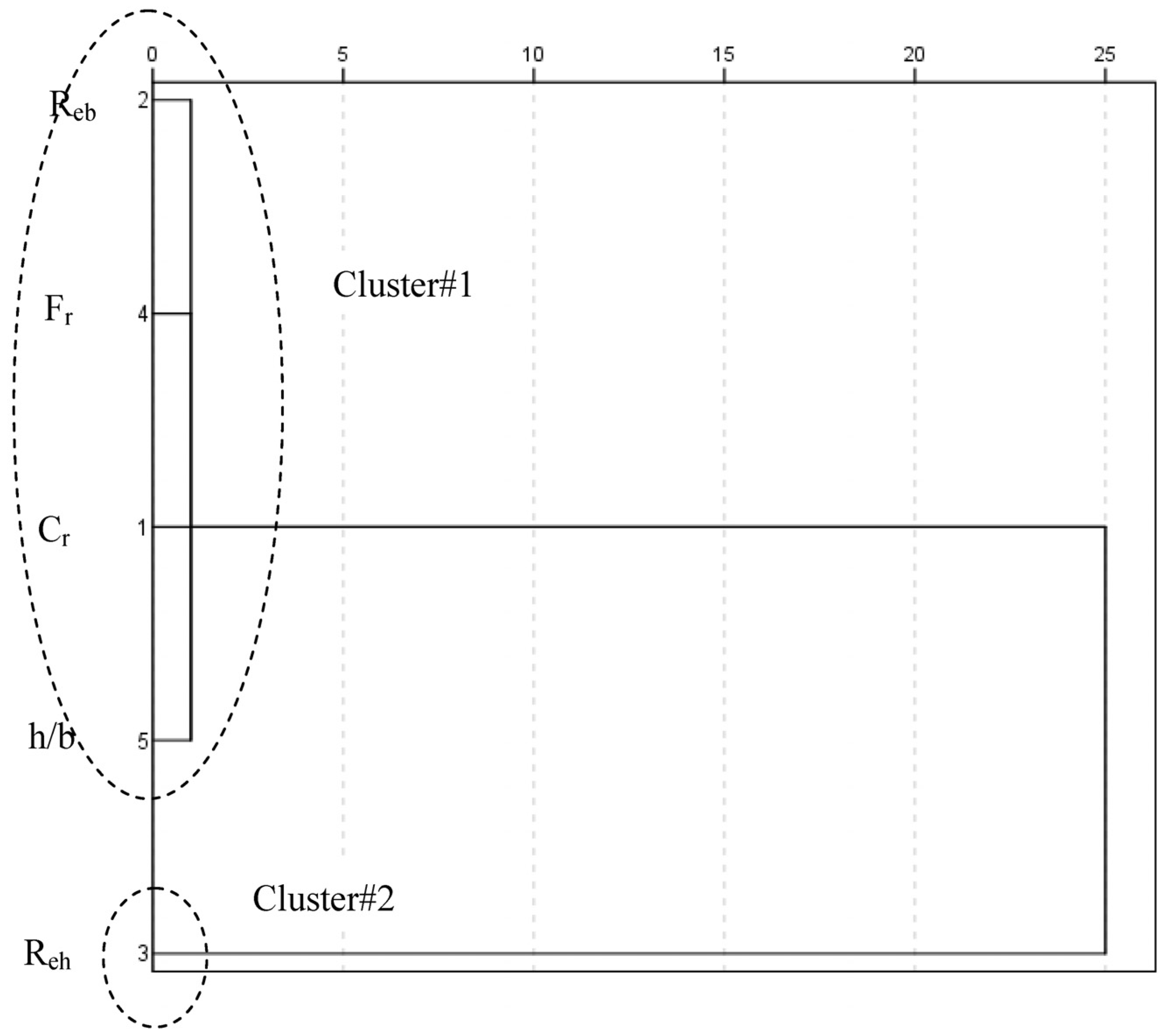

. The linkage method defines how the distance between two clusters is measured. Nearest neighbor, furthest neighbor, Centroid clustering, Median clustering, and Ward’s method are among those widely used. In this research, Ward’s method is applied. The main idea behind Ward’s method is that the linkage function specifying the distance between two clusters is computed as the increase in the “error sum of squares” (ESS) after fusing two clusters into a single cluster. Ward’s method seeks to choose the successive clustering steps so as to minimize the increase in ESS at each step.  shows similar behavior with Reb, Fr, h/b whereas Reh belongs to the single element cluster.

shows similar behavior with Reb, Fr, h/b whereas Reh belongs to the single element cluster.

4.6. Evaluation of the Statistical Techniques

while Reh is the second most influential parameter. Therefore, it is aimed to use both h/b and Reh in constructing the model.

while Reh is the second most influential parameter. Therefore, it is aimed to use both h/b and Reh in constructing the model.| Variables | Statistical procedures | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simple Correlation Analysis | Principal Component Analysis | Cluster Analysis | Multiple Linear Regression | Stepwise Regression | |

| Cr | √ | – | – | – | – |

| Reb | – | – | √ | – | – |

| Fr | √ | – | √ | – | – |

| h/b | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Reh | √ | √ | – | – | √ |

is both related to h/b and Reh as:

is both related to h/b and Reh as:

, because the variables that are employed to construct cannot define the structural behavior of the obstacles. Therefore, additional new parameter should be defined into the regression analysis.

, because the variables that are employed to construct cannot define the structural behavior of the obstacles. Therefore, additional new parameter should be defined into the regression analysis.4.7. Additional Parameter Definition

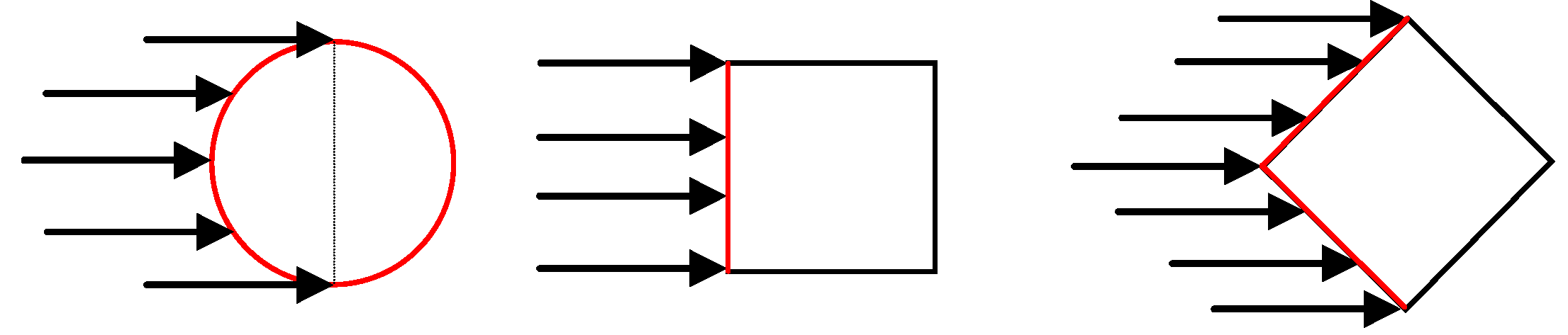

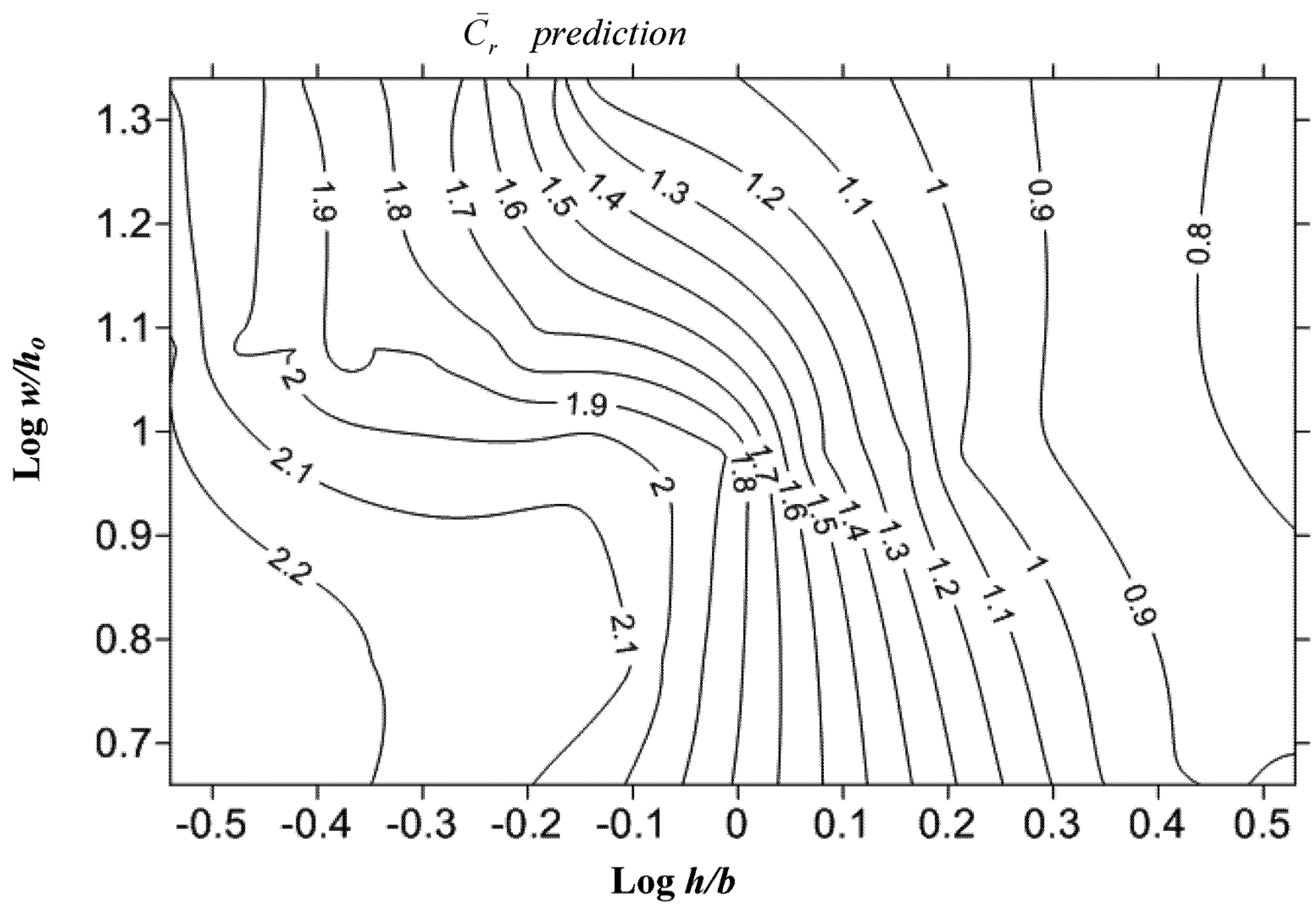

and others such as Reh, Reb, Fr and h/b in Figure 2. However, it is quite obvious in Figure 2a and the others that there is a linear pattern between the obstacles of different shape and scale, which can be described in general as y = ax + b. Therefore, it is necessary to include a parameter that describes the shape of the obstacles. In this study, wide variety of combination is tried. It is seen that the perimeter of circle, one side length and two side lengths for rectangular and diamond obstacles, respectively, are found to be correlated with

and others such as Reh, Reb, Fr and h/b in Figure 2. However, it is quite obvious in Figure 2a and the others that there is a linear pattern between the obstacles of different shape and scale, which can be described in general as y = ax + b. Therefore, it is necessary to include a parameter that describes the shape of the obstacles. In this study, wide variety of combination is tried. It is seen that the perimeter of circle, one side length and two side lengths for rectangular and diamond obstacles, respectively, are found to be correlated with  . This influence is described and proposed in this paper with a non-dimensional “shape of influence” parameter as w/ho, where w is perimeter of circles, length of one side for rectangular and summation length of two sides for diamonds in Figure 3, and ho is initial water depth as 20 mm.

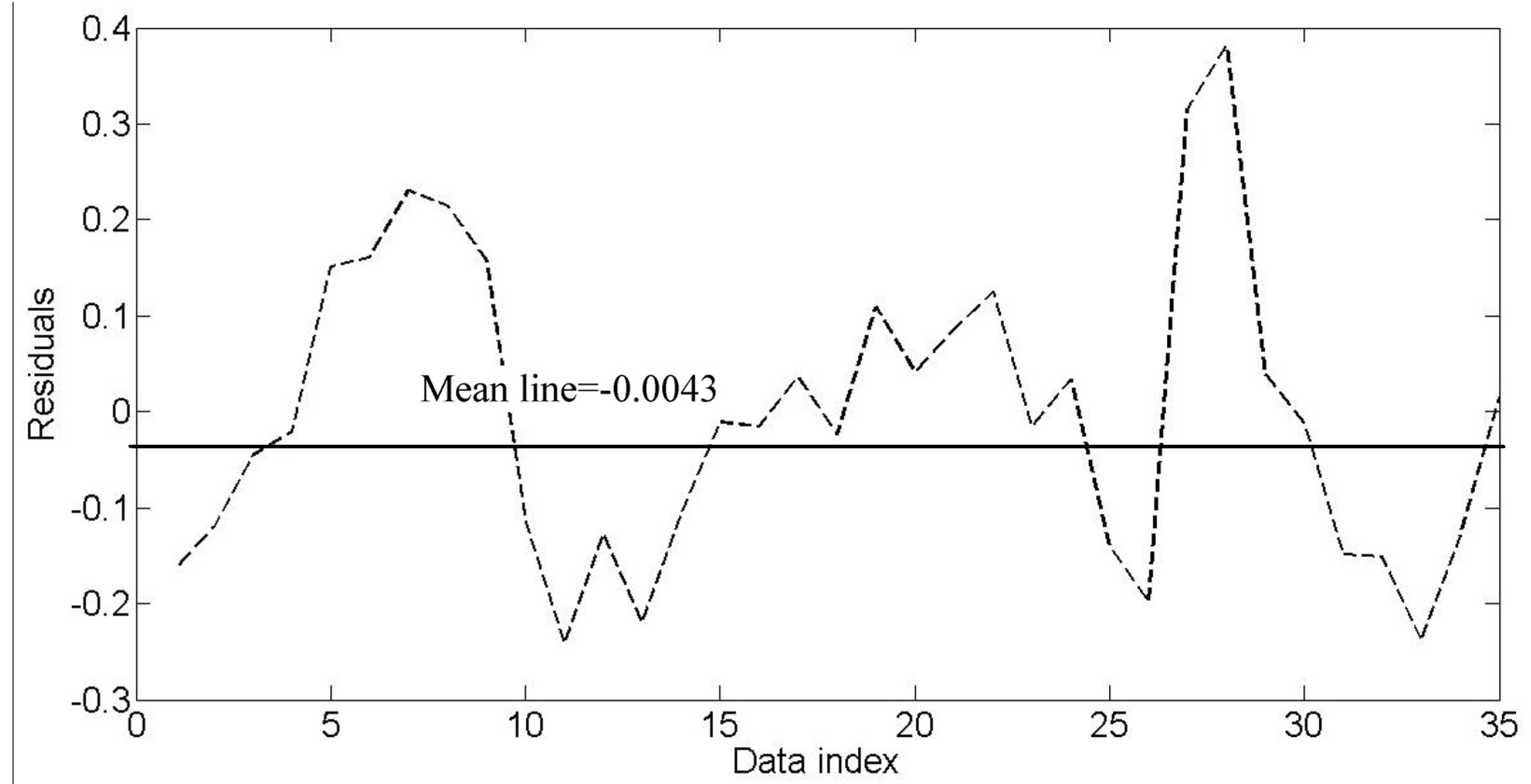

. This influence is described and proposed in this paper with a non-dimensional “shape of influence” parameter as w/ho, where w is perimeter of circles, length of one side for rectangular and summation length of two sides for diamonds in Figure 3, and ho is initial water depth as 20 mm. and both h/b and the newly proposed variable w/ho is investigated with linear regression models. The variable Reh is excluded from the analysis for the sake of parsimoniousity because its influence is less, with magnitude of 1/3 compared to h/b. As a thumb rule, a linear model gives good results with normally distributed variables. Therefore, log-transformed variables were used for both h/b and w/ho to regress. A stepwise linear regression procedure was employed. In the first step, log(h/b) was entered into the model by selection criteria that is mentioned in Section 4.3. As for the second step, log(w/ho) was placed into the model. As shown in Table 8, all variables are statistically significant. In addition, adjusted R2 value of the model increased to 0.86 as seen in Table 10. This is a satisfactory result when compared with the other models that are constructed in scope of this study. The collinearity diagnostics shows a tolerably collinearity problem, because the condition index is below 15 and VIF is smaller than 2 (Table 9). Therefore, new model is suggested which is in harmony with the regression assumptions as:

and both h/b and the newly proposed variable w/ho is investigated with linear regression models. The variable Reh is excluded from the analysis for the sake of parsimoniousity because its influence is less, with magnitude of 1/3 compared to h/b. As a thumb rule, a linear model gives good results with normally distributed variables. Therefore, log-transformed variables were used for both h/b and w/ho to regress. A stepwise linear regression procedure was employed. In the first step, log(h/b) was entered into the model by selection criteria that is mentioned in Section 4.3. As for the second step, log(w/ho) was placed into the model. As shown in Table 8, all variables are statistically significant. In addition, adjusted R2 value of the model increased to 0.86 as seen in Table 10. This is a satisfactory result when compared with the other models that are constructed in scope of this study. The collinearity diagnostics shows a tolerably collinearity problem, because the condition index is below 15 and VIF is smaller than 2 (Table 9). Therefore, new model is suggested which is in harmony with the regression assumptions as:

| Stepwise Model | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | Significance | Correlations | Partial | Part | Collinearity Statistics | Collinearity Diagnostics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. Error | Beta | Zero order | Tolerance | VIF | Eigen value | Cond. Index | ||||||

| Step 1 | Constant | 1.55 | 0.05 | – | 29.48 | 0.00 | – | – | – | – | – | 1.51 | 1.00 |

| Step 1 | log(h/b) | −1.25 | 0.17 | −0.78 | −7.20 | 0.00 | −0.78 | −0.78 | −0.78 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.49 | 1.75 |

| Step 2 | Constant | 2.53 | 0.13 | – | 19.40 | 0.00 | – | – | – | – | – | 2.41 | 1.00 |

| Step 2 | log(h/b) | −1.74 | 0.12 | −1.09 | −14.28 | 0.00 | −0.78 | −0.93 | −0.93 | 0.73 | 1.37 | 0.57 | 2.05 |

| Step 2 | log(w/ho) | −1.05 | 0.14 | −0.59 | −7.73 | 0.00 | −0.02 | −0.81 | −0.50 | 0.73 | 1.37 | 0.02 | 10.88 |

| Model | R | R Square | Adjusted R Square | Std. Error of the Estimate | R Square Change | F Change | df1 | df2 | Sig. F Change | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | 0.782 | 0.61 | 0.60 | 0.27 | 0.61 | 51.84 | 1.00 | 33.00 | 0.00 | |

| step 2 | 0.930 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.16 | 0.25 | 59.79 | 1.00 | 32.00 | 0.00 | |

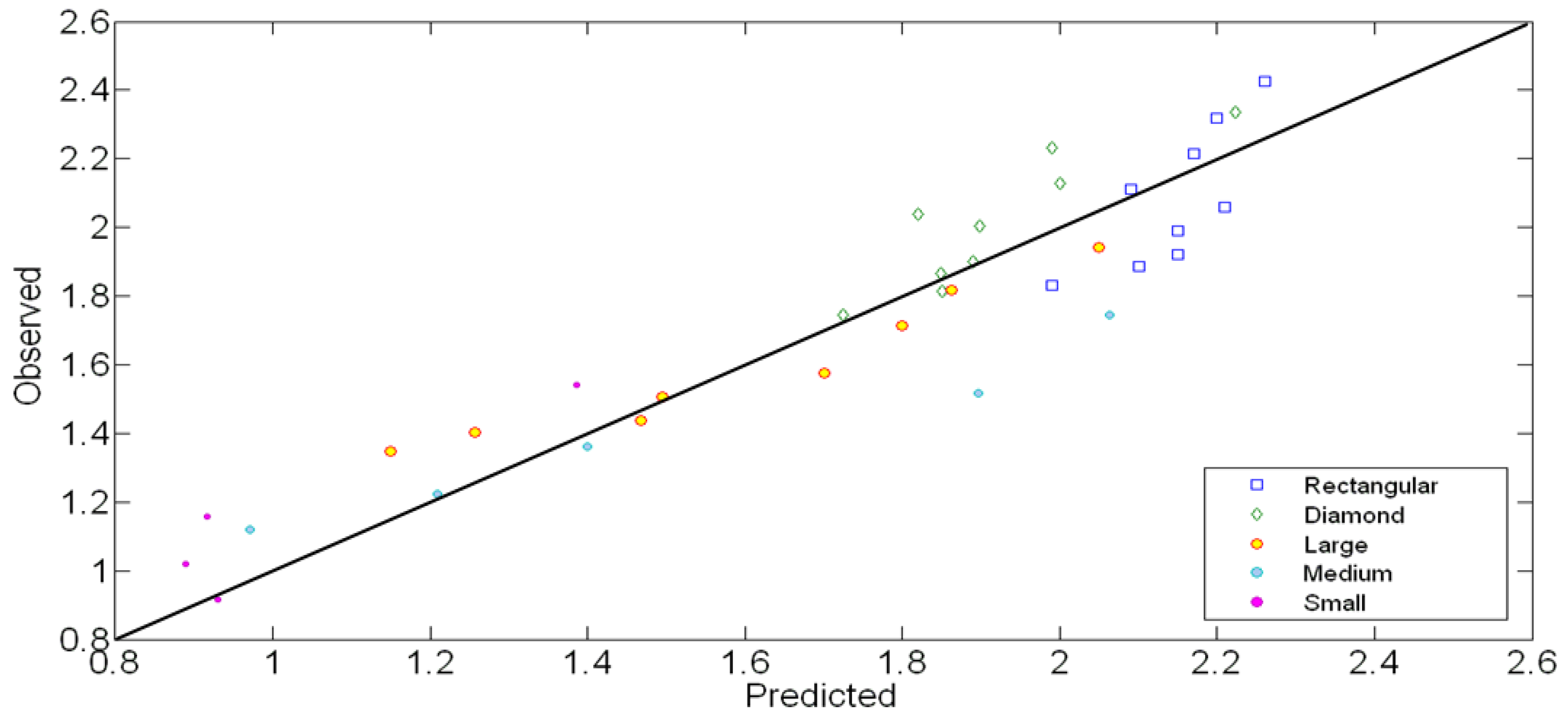

is highly dependent on these parameters. In addition, newly developed parameter w/ho is capable of describing the behavior of

is highly dependent on these parameters. In addition, newly developed parameter w/ho is capable of describing the behavior of  in an efficient way. Contrary to the Figure 1, there are no any transitional zones dependent on obstacles in Figure 4 with proposed w/ho variable. One can easily predict the

in an efficient way. Contrary to the Figure 1, there are no any transitional zones dependent on obstacles in Figure 4 with proposed w/ho variable. One can easily predict the  by just inserting w/ho and h/b on the figure, without describing the shape of structure in advance.

by just inserting w/ho and h/b on the figure, without describing the shape of structure in advance. with h/b and proposed w/ho.

with h/b and proposed w/ho.

5. Evaluation of the Proposed Model for Mean Normalized Force Computation

| Obstacle shape | Mean absolute relative error (MARE) | Mean squared error (MSE) | Coefficient of determination (R2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rectangular | 0.0655 | 0.0241 | 0.5924 |

| Diamond | 0.0508 | 0.0165 | 0.7887 |

| Large | 0.0645 | 0.0123 | 0.9309 |

| Medium | 0.1086 | 0.0535 | 0.9563 |

| Small | 0.1339 | 0.0247 | 0.8522 |

| Total | 0.0755 | 0.0237 | 0.8643 |

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

List of Symbols

| C1,1; C1,2 | Inertia coefficients |

| Cd | Drag coefficient |

| CF | Force coefficient |

| Cr | Normalized resistance coefficient |

| Timely averaged resistance coefficient |

| C | Case weights |

| F | Force on the wall |

| Fb | Buoyant force |

| Fhs | Hydrostatic forces |

| Fhd | Hydrodynamic forces |

| Fimp | Impulsive forces |

| Fi | Surge force |

| Fl | Force on the wall due to a runup |

| Fr | Froude number |

| Fx | Force in the x-direction |

| H | Wave height at the wall |

| M | Moment on the wall corresponding to the force F |

| Ml | moment corresponding to the force Fl |

| V | Volume of water |

| R2 | Square of multiple correlation coefficient |

| Adjusted R2 |

| Reh | Flow Reynolds number |

| Reb | Object Reynolds number |

| b | Width of the object |

| b·h | Area of the structural element |

| g | Acceleration due to gravity |

| h | Bore height |

| hus | Water depth upstream of the structure |

| hds | Water depth downstream of the structure |

| ho | Initial water depth |

| h1 | height of impoundment behind the gate |

| t | Time |

| u | Flow velocity component orthogonal to the structure |

| w | Shape of influence parameters |

Greek letters

| ρ | Density of the fluid |

| γ | Specific weight |

| υ | Kinematic viscosity |

References

- Yang, C.; Lin, B.; Jiang, C.; Lin, Y. Predicting near-field dam break flow and impact force using 3D model. J. Hydraul. Res. 2010, 48, 784–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanson, H. The Hydraulics of Open Channel Flow: An Introduction, 2nd ed; Butterwort-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ritter, A. Die fortpflanzung der wasserwellen. Zeitschrift des Vereines Deutscher Ingenieure 1892, 36, 947–954. [Google Scholar]

- FEMA 55, Coastal Construction Manual, 3rd edFederal Emergency Management Agency: Jessup, MD, USA, 2003.

- Kaplan, P.; Murray, J.J.; Yu, W.C. Theoretical Analysis of Wave Impact Forces on Platform Deck Structures. In Proceedings of the Offshore Mechanics and Arctic Engineering Conference, OMAE Copenhagen, Denmark, 18–22 June 1995; 1A, pp. 353–374.

- Cumberbatch, E. The impact of water wedge on a wall. J. Fluid Mech. 1960, 7, 353–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, R.H. Tsunami surge forces. J. Waterw. Harb. Div. ASCE 1967, 93, 201–231. [Google Scholar]

- Ramsden, J.D. Tsunamis: Forces on a Vertical Wall caused by Long Waves, Bores, and Surges on a Dry Bed. Ph.D. Thesis, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- City and County of Honolulu Building Code (CCH); Chapter 16, Article 11; Department of Planning and Permitting of Honolulu: Honolulu, HI, USA, 2000.

- Dames and Moore. In Design and Construction Standards for residential Construction in Tsunami Prone Areas in Hawaii; Prepared for Federal Emergency Management Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 1980.

- Mikhaylov, Y.; Robertson, I.N. Evaluation of Prototypical Reinforced Concrete Building Performance when Subjected to Tsunami Loading; Research Report UHM/CEE/09-01; Sage Publications: New Delhi, India, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Soares-Frazão, S. Experiments of dam-break wave over triangular bottom sill. J. Hydraul. Res. 2007, 45, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, S.; Chaudhry, M.H. Dam-break flows in curved channel. J. Hydraul. Eng. ASCE 1989, 115, 1465–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagatay, H.; Kocaman, S. Experimental study of tail water level effects on dam-break flood wave propagation. In Proceedings of River Flow Conference, Cesme, Turkey, 3–5 September 2008; 1, pp. 635–644.

- Aureli, F.; Maranzoni, A.; Mignosa, P.; Ziveri, C. Dam-break flows: Acquisition of experimental data through an imaging technique and 2D numerical modelling. J. Hydraul. Eng. ASCE 2008, 134, 1089–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oertel, M.; Bung, D.B. Initial stage of two-dimensional dam-break waves: Laboratory versus VOF. J. Hydraul. Res. 2012, 50, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares-Frazão, S.; Zech, Y. Dam-break in channels with 90-degree bend. J. Hydraul. Res. 2002, 128, 956–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanson, H. Application of the method of characteristics to the dam break wave problem. J. Hydraul. Res. 2009, 1, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnason, H. Interactions between Incident Bore and a Free-Standing Coastal Structure. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Arnason, H.; Petroff, C.; Yeh, H. Tsunami bore impingement onto a vertical column. J. Disaster Res. 2009, 4, 391–403. [Google Scholar]

- Yeh, H.; Ghazali, A.; Marton, I. Experimental study of bore run-up. J. Fluid Mech. 1989, 206, 563–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Duricic, J.; Erdik, T.; Pektaş, A.O.; Van Gelder, P.H.A.J.M. Mean Normalized Force Computation for Different Types of Obstacles due to Dam Break Using Statistical Techniques. Water 2013, 5, 560-577. https://doi.org/10.3390/w5020560

Duricic J, Erdik T, Pektaş AO, Van Gelder PHAJM. Mean Normalized Force Computation for Different Types of Obstacles due to Dam Break Using Statistical Techniques. Water. 2013; 5(2):560-577. https://doi.org/10.3390/w5020560

Chicago/Turabian StyleDuricic, Jasna, Tarkan Erdik, Ali Osman Pektaş, and Petrus H.A.J.M Van Gelder. 2013. "Mean Normalized Force Computation for Different Types of Obstacles due to Dam Break Using Statistical Techniques" Water 5, no. 2: 560-577. https://doi.org/10.3390/w5020560

APA StyleDuricic, J., Erdik, T., Pektaş, A. O., & Van Gelder, P. H. A. J. M. (2013). Mean Normalized Force Computation for Different Types of Obstacles due to Dam Break Using Statistical Techniques. Water, 5(2), 560-577. https://doi.org/10.3390/w5020560