Mechanisms and Empirical Analysis of How New Quality Productive Forces Drive High-Quality Development to Enhance Water Resources Carrying Capacity in the Weihe River Basin

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Mechanisms Through Which High-Quality Development Driven by New Quality Productive Forces Enhances Water Resources Carrying Capacity

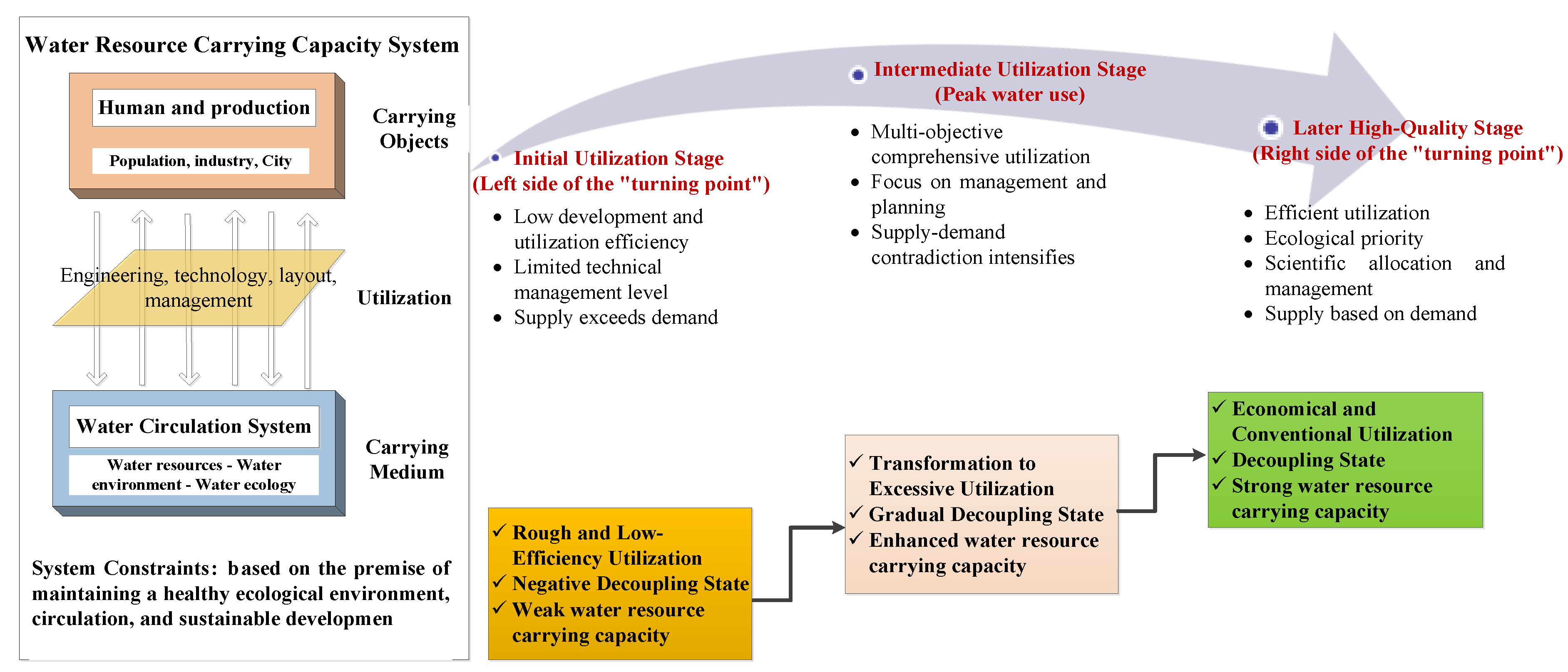

2.1.1. Theory of Water Resources Carrying Capacity

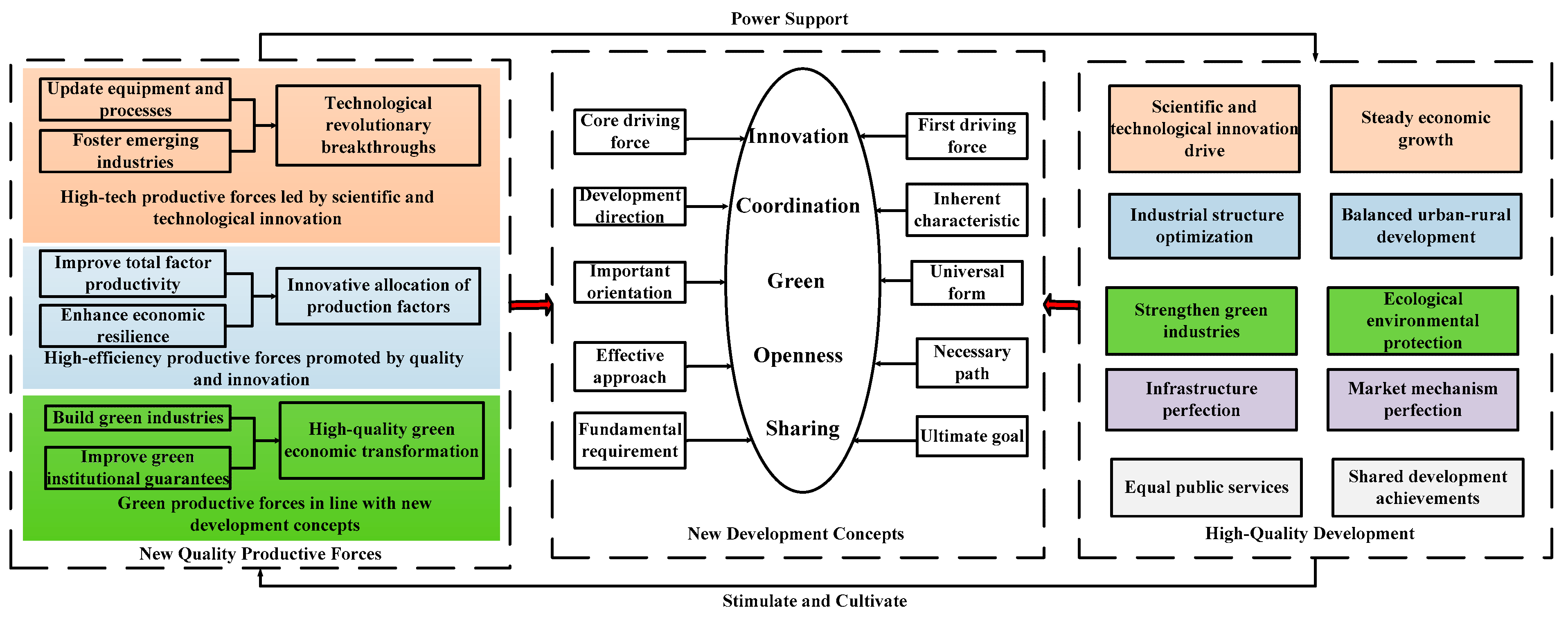

2.1.2. Interactive Relationship Between New Quality Productive Forces and High-Quality Development

- (1)

- Internal alignment between the green transformation of new quality productive forces and high-quality development

- (2)

- Connotations of high-quality development and its implicit resource–environmental logic

- (3)

- Interaction mechanism between new quality productive forces and high-quality development

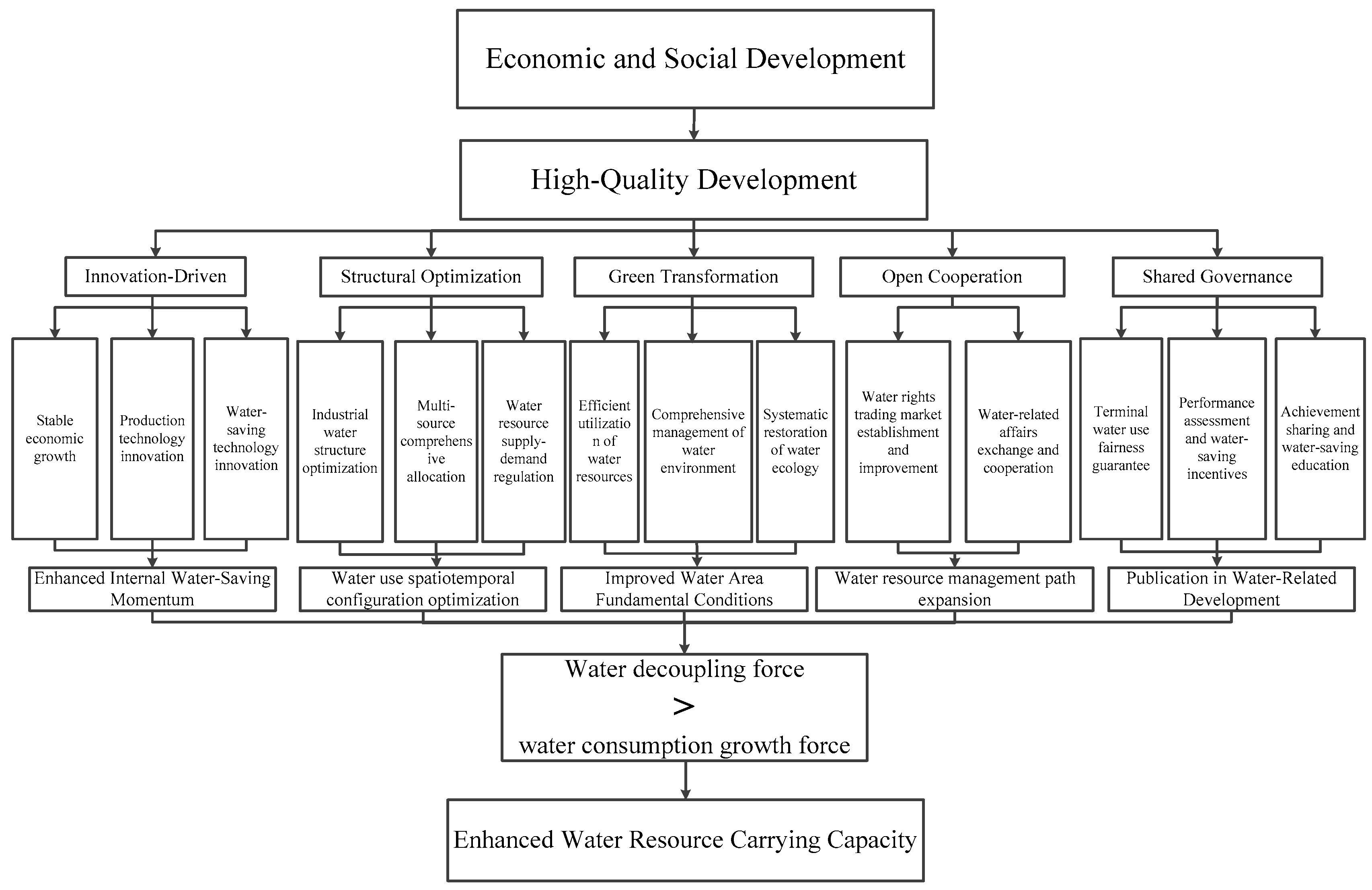

2.1.3. Mechanisms Through Which High-Quality Development Enhances Water Resources Carrying Capacity

2.2. Evaluation System and Methods

2.2.1. Construction of the Evaluation Indicator Systems for High-Quality Development and Water Resources Carrying Capacity

- (1)

- Evaluation indicator system for high-quality development

- (2)

- Evaluation indicator system for water resources carrying capacity

2.2.2. Semi-Trapezoidal Fuzzy Membership Comprehensive Index Model

- Step 1: Data standardization

- For positive indicators:For negative indicators:where eij denotes the observed value of the j indicator in the i region. aij and Aij represent the theoretical lower and upper bounds, respectively, of the j indicator for the i sample. denotes the fuzzy membership degree of the j indicator for the i region.

- Step 2: Determination of indicator weights

- The weight of each indicator is calculated as:where denotes the weight of the j indicator. To avoid bias arising from single weighting methods and to improve the accuracy of weight assignment, a combined subjective–objective weighting approach was adopted. Specifically, the entropy weight method (EWM) was used to determine objective weights, while the analytic hierarchy process (AHP) was applied to obtain subjective weights. Here, represents the objective weight, represents the subjective weight, and is the combination coefficient, which is generally set to 0.5.

- Step 3: Calculation of the comprehensive index

- The comprehensive index is calculated using the weighted average method:where denotes the comprehensive index of high-quality development or the comprehensive index of water resources carrying capacity for the i region.

2.2.3. Coupling Coordination Degree Model

- Step 1: Calculation of the coupling degree (C)

- The coupling degree, which measures the degree of interaction and interdependence between the two systems, is calculated as:where Ue denotes the comprehensive index of high-quality development, Uw denotes the comprehensive index of water resources carrying capacity, and C represents the coupling degree. The value of C ranges from 0 to 1. A value closer to 1 indicates a stronger coupling relationship between the two systems and a tendency toward the formation of a more ordered structure, whereas lower values indicate a weaker and more disordered interaction.

- Step 2: Calculation of the comprehensive system index (T)

- The comprehensive system index, which reflects the overall development level of the two systems, is calculated as:where β1 and β2 are weighting coefficients. Based on the assumed equal importance of the two systems, the weights are set as β1 = β2 = 0.5.

- Step 3: Calculation of the coordination degree (D)

- The coupling coordination degree is calculated as:

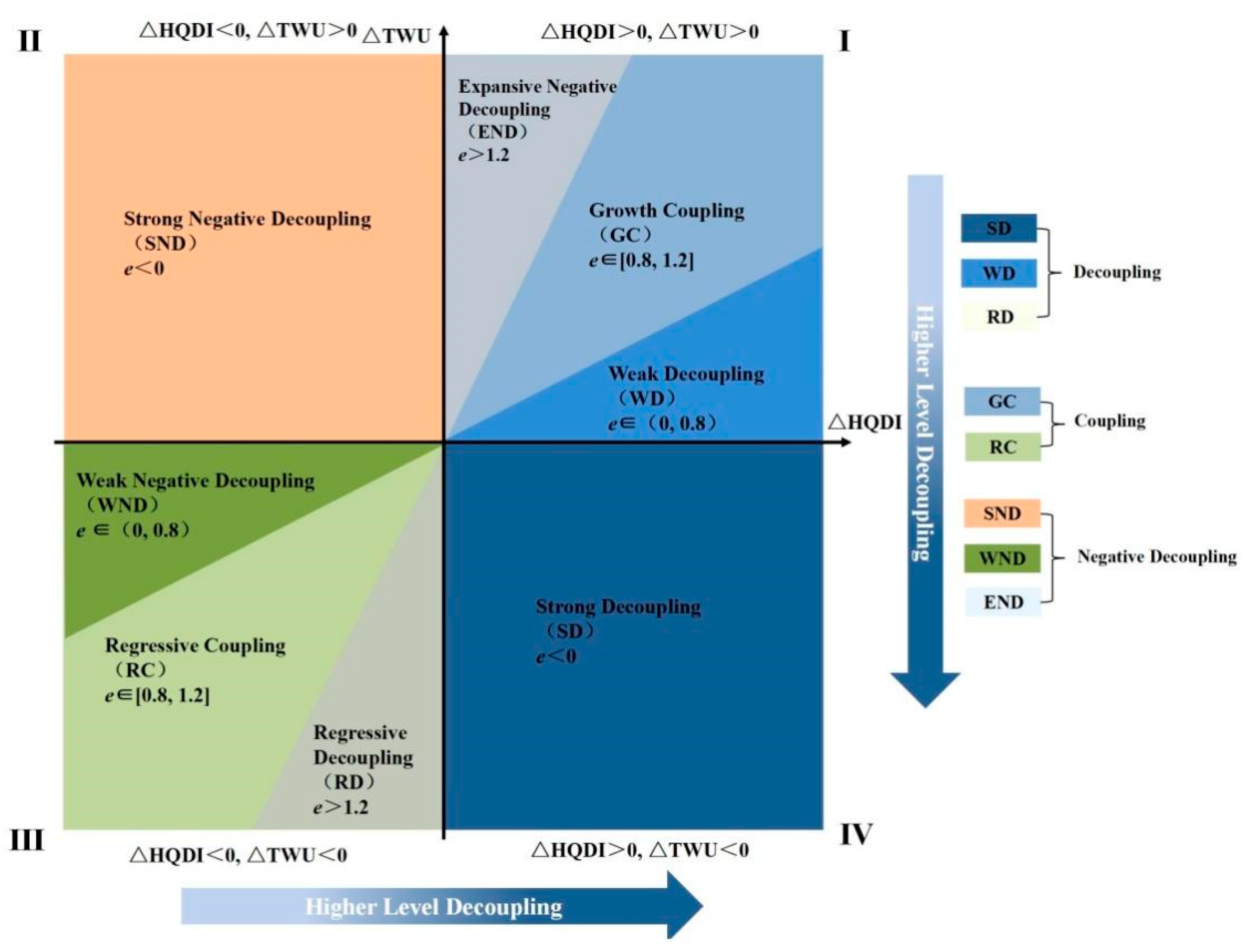

2.2.4. Tapio Decoupling Model

2.2.5. LMDI Driving Factor Decomposition Model

2.3. Study Area and Data Sources

2.3.1. Overview of the Study Area

2.3.2. Data Sources

- (1)

- Socioeconomic data

- (2)

- Resource and environmental data

- (3)

- Science and technology innovation data

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Analysis of the Interaction Between High-Quality Development and Water Resources Carrying Capacity in the Weihe River Basin

3.1.1. Evaluation of the High-Quality Development Index in the Weihe River Basin

3.1.2. Evaluation of the Water Resources Carrying Capacity Index in the Weihe River Basin

3.1.3. Robustness and Scientific Linkage Verification of Composite Indices

3.1.4. Evaluation of the Coupling Coordination Between High-Quality Development Index and Water Resources Carrying Capacity Index in the Weihe River Basin

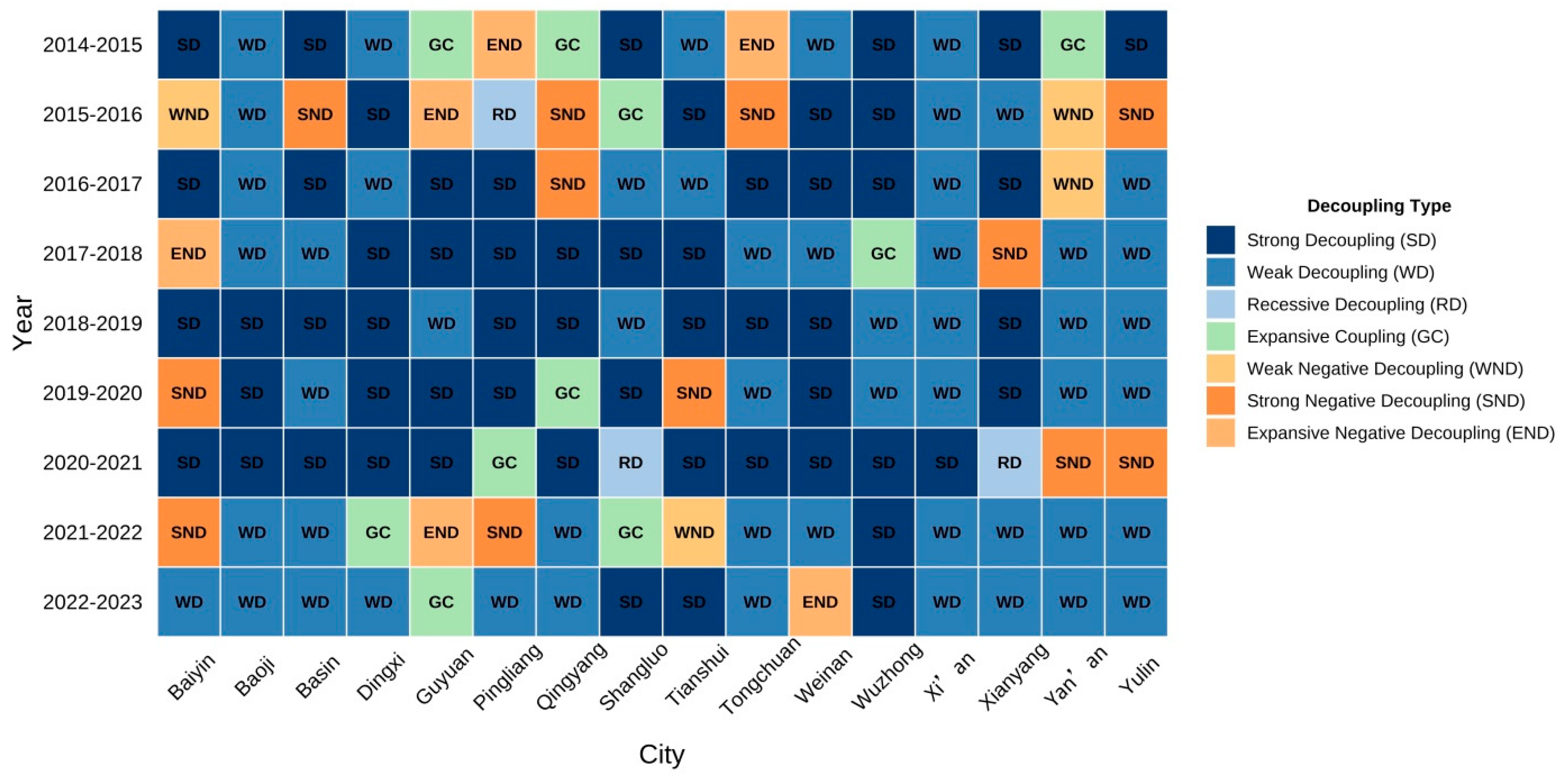

3.2. Decoupling State Analysis Between Water Resources Utilization and High-Quality Economic Development in the Weihe River Basin

3.2.1. Temporal Evolution Characteristics

3.2.2. Spatial Differentiation Characteristics

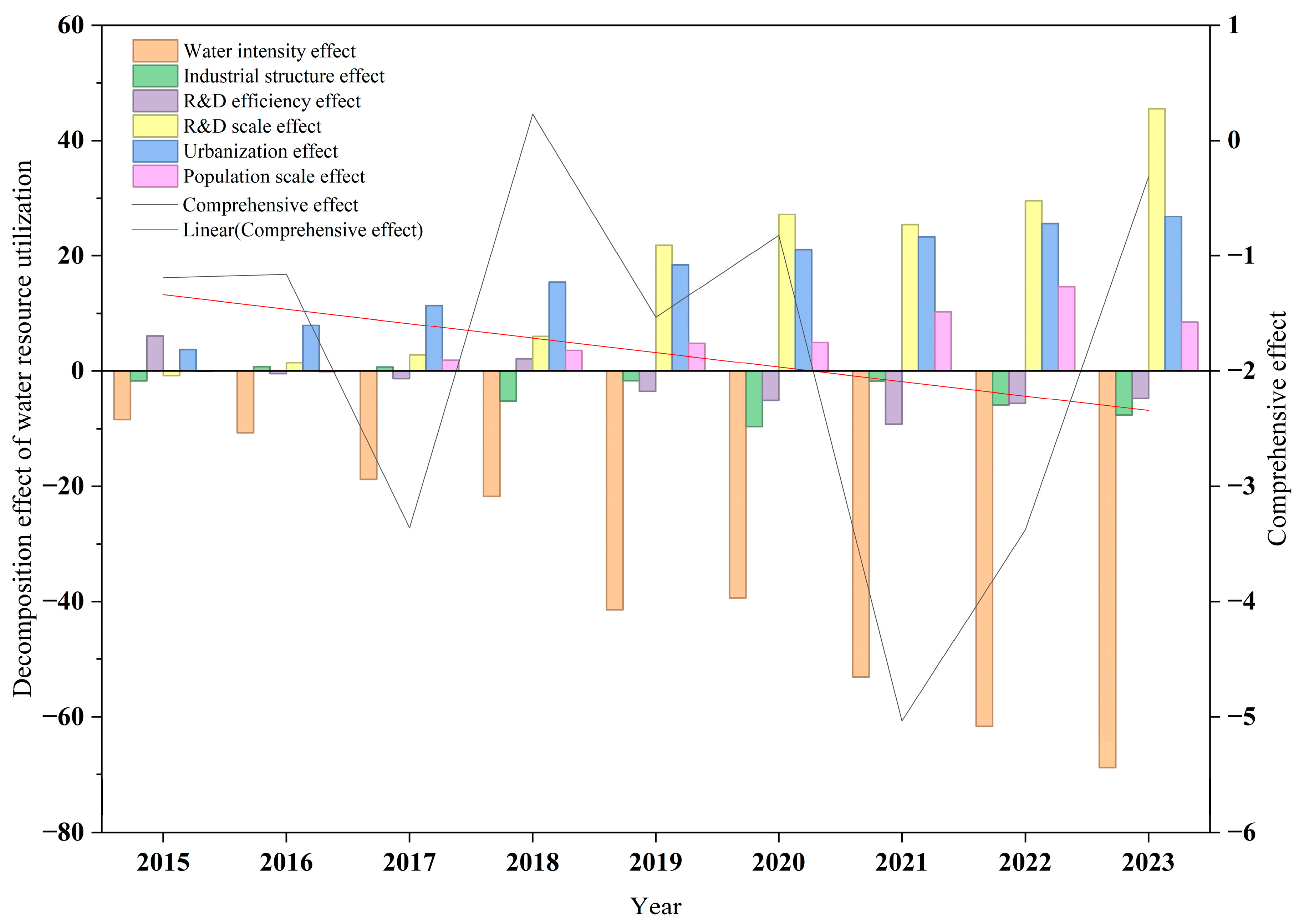

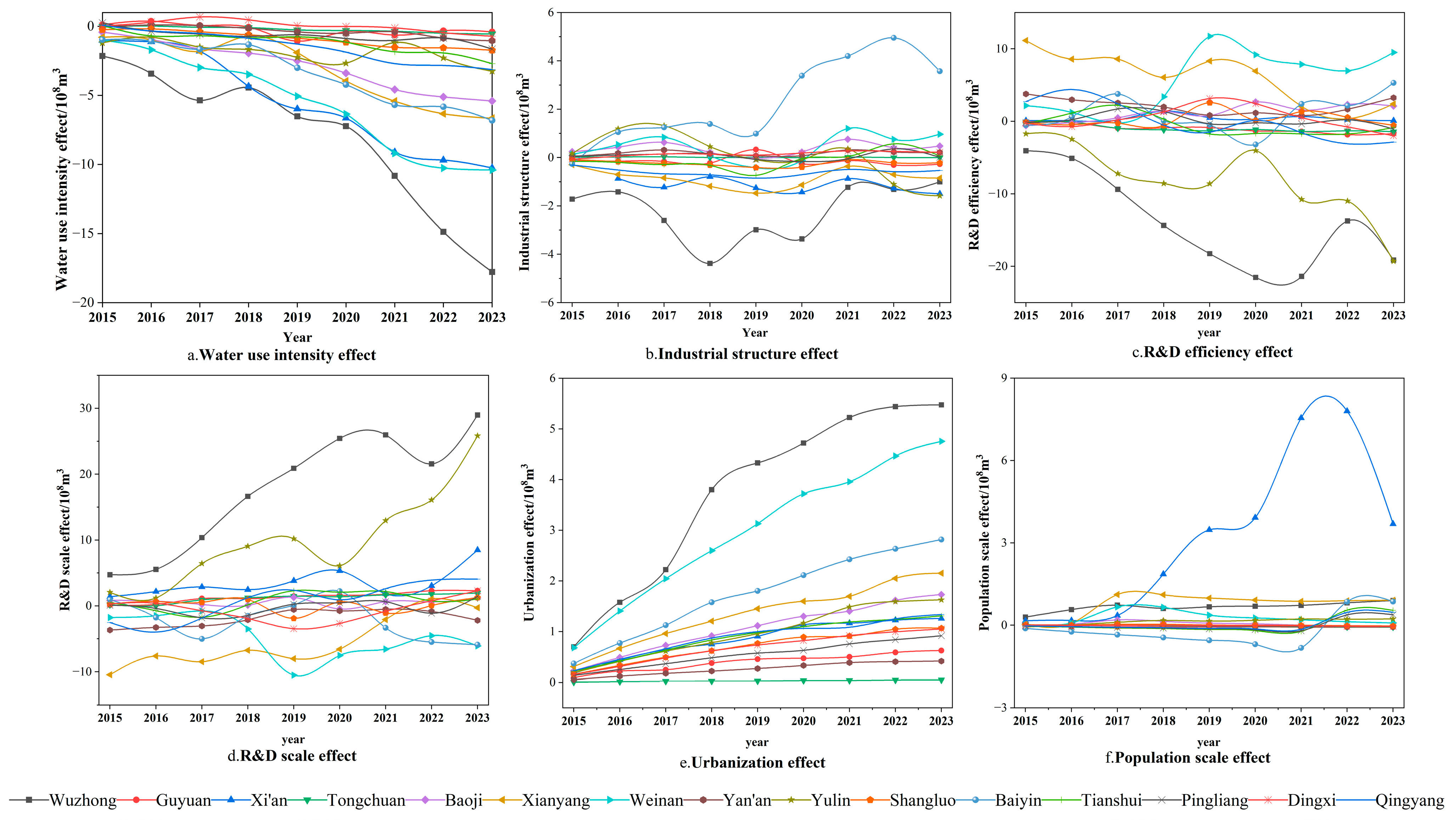

3.3. Decoupling Drivers Analysis Based on the LMDI Decomposition Model

3.3.1. Overall Decoupling Drivers Analysis of the Weihe River Basin

3.3.2. Analysis of Decoupling Drivers in Cities of the Weihe River Basin

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yang, D.W.; Yang, Y.T.; Xia, J. Hydrological Cycle and Water Resources in a Changing World: A Review. Geosci. Front. 2021, 12, 101159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.F.; Wang, Y.C.; Huang, C.X.; Li, F.Q.; Wu, G.D. Multi-Objective Optimization of Water Resource Allocation with Spatial Equilibrium Considerations: A Case Study of Three Cities in Western Gansu Province. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Li, J.; Zhou, Z.X. Water Resources Security Pattern of the Weihe River Basin Based on Spatial Flow Model of Water Supply Service. Geogr. Sci. 2021, 41, 350–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mijic, A.; Liu, L.; O’Keeffe, J.; Dobson, B.; Chun, K.P. A Meta-Model of Socio-Hydrological Phenomena for Sustainable Water Management. Nat. Sustain. 2024, 7, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javanbakht-Sheikhahmad, F.; Rostami, F.; Azadi, H.; Veisi, H.; Amiri, F.; Witlox, F. Agricultural Water Resource Management in the Socio-Hydrology: A Framework for Using System Dynamics Simulation. Water Resour. Manag. 2024, 38, 1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, K.; Zghibi, A.; Elomri, A.; Mazzoni, A.; Triki, C. A Literature Review on System Dynamics Modeling for Sustainable Management of Water Supply and Demand. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gain, A.; Hossain, S.; Benson, D.; Di Baldassarre, G.; Giupponi, C.; Huq, N. Social-Ecological System Approaches for Water Resources Management. Environ. Politics 2021, 30, 1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roobavannan, M.; Kandasamy, J.; Vigneswaran, S. Policy Measures to Lead Sustainable Development of Agriculture Catchment: Socio-Hydrology Modeling Insights. Hydrology 2025, 12, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel, N.; Shaw, R. Challenges of Urban Water Security and Drivers of Water Scarcity in Kathmandu Valley, Nepal. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.Y.; Zhang, S.L.; Gao, C.; Tang, X.P. Coupling Coordination and Driving Mechanisms of Water Resources Carrying Capacity under the Dynamic Interaction of the Water–Social–Economic–Ecological Environment System. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 920, 171011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.Y.; Cao, Y. Research on Provincial Water Resources Carrying Capacity and Coordinated Development in China Based on Combined Weighting TOPSIS Model. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 12497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.R.; Bee, H.; Wang, Y.; He, J.J. Coupling Coordination and Sustainability among Water Resource Carrying Capacity, Urbanization, and Economic Development Based on the Integrated Model. Front. Environ. Sci. 2025, 13, 1563946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.Q.; Ji, D.D.; Yang, L. Comprehensive Evaluation of Water Resources Carrying Capacity in Henan Province Based on Entropy Weight TOPSIS–Coupling Coordination–Obstacle Model. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 115820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.F.; Jiang, C.H. Research Progress on High-Quality Development in the Yellow River Basin under the Rigid Constraint of Water Resources. Water Resour. Econ. 2023, 41, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Lu, Z.H.; Yun, X.Z. Coupling Coordination and Driving Mechanism between Water Resources Carrying Capacity and High-Quality Development in the Yellow River Basin. Chin. J. Agric. Resour. Reg. Plan. 2025, 46, 91. Available online: https://link.cnki.net/urlid/11.3513.S.20240516.1435.013 (accessed on 26 January 2026).

- Deng, L.L.; Yin, J.B.; Tian, J.; Li, Q.X.; Guo, S. Comprehensive Evaluation of Water Resources Carrying Capacity in the Han River Basin. Water 2021, 13, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.H.; Xia, F.Q.; Yang, D.G.; Huo, J.W. Comprehensive Evaluation of Water Resource Carrying Capacity in Northwest China. Water 2025, 17, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Lyu, L.; Wang, N. New Quality Productivity and China’s Strategic Shift Towards Sustainable and Innovation-Driven Economic Development. J. Interdiscip. Insights 2024, 3, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, X.K.; Zhao, W.L.; Du, H. Study on the Impact of New Quality Productive Forces on Agricultural Green Production Efficiency. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 20625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.S.; Wang, R.X.; Zhang, S.F. Digital Economy, Green Innovation Efficiency, and New Quality Productive Forces: Empirical Evidence from Chinese Provincial Panel Data. Sustainability 2025, 17, 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.Q.; Zhang, H.; Guo, C.Y.; Yang, Y.C. New Quality Productive Forces Enabling High-Quality Development: Mechanism, Measurement, and Empirical Analysis. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, K.R.; Jin, T.Y.; Zhao, Q. Empowering High-Quality Development with New Productive Forces. Nanjing Soc. Sci. 2024, 1, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Guo, W.J. Measurement of China’s New Productive Forces and Its Impact on High-Quality Economic Development. Financ. Dev. Res. 2024, 7, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardi, I.; Mutig Idroes, G.; Márquez-Ramos, L.; Noviandy, T.R.; Idroes, R. Inclusive innovation and green growth in advanced economies. Sustain. Futures 2025, 9, 100540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwilinski, A.; Dacko-Pikiewicz, Z.; Szczepanska-Woszczyna, K.; Lyulyov, O.; Pimonenko, T. The role of innovation in the transition to a green economy: A path to sustainable growth. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2025, 11, 100530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Ahmad, S.; Noureen, S.; Salman, M. Green growth and sustainable energy transitions: Evaluating the critical role of technology, resource efficiency, and innovation in Europe’s low-carbon future. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2025, 12, 1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Khan, T.; Ahmad, M. The Role of Technological Innovation in Sustainable Growth: Exploring the Economic Impact of Green Innovation and Renewable Energy. Environ. Chall. 2025, 18, 101109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabbir, M.N.; Linh, D.T. Globalizing Green Innovation: Impact on Green GDP and Pathways to Sustainability. Res. Econ. 2025, 79, 101042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.H.; Li, Z.G.; Zhang, Z.X.; Yu, K.Y. Coordinating high-quality economic development and water resources carrying capacity in the Yangtze River Basin cities: Achieving sustainable development goals. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2025, 60, 102502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Gu, T.Y.; Shi, Y. The influence of new quality productive forces on high-quality agricultural development in China: Mechanisms and empirical testing. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.C.; Liu, J.H. Decoupling Analysis of Water Resources Utilization Efficiency and High-Quality Economic Development in the Yellow River Basin. Resour. Ind. 2023, 25, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.Z.; Li, L.J.; Li, J.Y. Comprehensive Evaluation of Water Resources Carrying Capacity in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Region Based on Quantity–Quality–Water Bodies–Flow. Resour. Sci. 2020, 42, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.X.; Xu, L. The Strategic Significance and Realization Path of Accelerating the Formation of New Quality Productive Forces. Res. Financ. Econ. 2024, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.F.; Shen, D.J. The Impact of High-Quality Development on Water Resources Carrying Capacity in the Yellow River Basin. J. Environ. Econ. Res. 2019, 4, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.C.; Lin, X.; He, Z.Q. A Study on the Decoupling Relationship between High-Quality Economic Development and Water Resource Consumption in the Yellow River Basin. Econ. Manag. Rev. 2022, 38, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.; Li, S.H. Measuring the Level of High-Quality Economic Development in China in the New Era. J. Quant. Tech. Econ. 2018, 35, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.W.; Yan, M.; Gao, Y.; Wang, Y.Q.; Dai, X.H. Evaluation System for Assessing the Operational Efficiency of Urban Combined Sewer Systems Using AHP–Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation: A Case Study. Water 2023, 15, 3434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Jiao, M.; Zhang, J. Coupling Coordination and Interactive Response Analysis of Ecological Environment and Urban Resilience in the Yangtze River Economic Belt. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, S.; Jia, X.; Zhao, Y.; Luo, M.; Wang, H.; Zhao, M. The Coupling Coordination Relationship Between Urbanization and the Eco-Environment in Resource-Based Cities, Loess Plateau, China. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2024, 13, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Z.C.; Li, L.; Huang, M.; Tao, Z.M.; Shi, X.T.; Li, T. Spatiotemporal evolution and decoupling effects of sustainable water resources utilization in the Yellow River Basin: Based on three-dimensional water ecological footprint. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 366, 121846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Qin, C.; Han, Y. The Driving Effects of the Total Water Use Evolution in China from 1965 to 2019. Water 2023, 15, 3572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Han, Y.; Li, H.; Feng, K. Understanding Agricultural Water Consumption Trends in Henan Province: A Spatio-Temporal and Determinant Analysis Using Geospatial Models. Agriculture 2024, 14, 2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.G.; Peng, A.B.; Hu, S.R.; Shi, Y.; Lu, L.; Aorui, B. Dynamic Successive Assessment of Water Resource Carrying Capacity Based on System Dynamics Model and Variable Fuzzy Pattern Recognition Method. Water 2024, 16, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Zhao, X.C.; Yan, B.J.; Fan, J.R.; Wang, M.M.; Liu, M.Q. How Does the Coupling Coordination between High-Quality Development and Eco-Environmental Carrying Capacity in the Yellow River Basin over Time. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1403265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tal, A. Seeking Sustainability: Israel’s Evolving Water Management Strategy. Science 2006, 313, 1081–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Criterion Layer | Primary Indicator | Secondary Indicator | Calculation Method and Indicator Direction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Innovation | Technological innovation | R&D expenditure intensity (X1) | R&D expenditure/GDP (%), + |

| Patents per 10,000 people (X2) | Total patents granted/total population (per 10,000 persons), + | ||

| Intensity of fiscal science and technology expenditure (X3) | Science & technology expenditure/total fiscal expenditure (%), + | ||

| GDP per capita (X4) | GDP/total population (CNY), + | ||

| Coordination | Industrial structure | Advanced industrial structure index (X5) | Tertiary industry output/Secondary industry output, + |

| Rationalization of industrial structure index (X6) | (Primary industry/GDP × 1) + (Secondary industry/GDP × 2) + (Tertiary industry/GDP × 3), + | ||

| Urban–rural development | Urbanization rate (X7) | Urban population/total population (%), + | |

| Regional income level (X8) | Regional GDP per capita/national GDP per capita (%), + | ||

| Urban–rural income ratio (X9) | Urban per capita disposable income/rural per capita disposable income, − | ||

| Green | Environmental quality | Green coverage rate of built-up areas (X10) | Green coverage rate of built-up areas (%), + |

| Pollution reduction | Centralized wastewater treatment rate (X11) | Centralized wastewater treatment rate (%), + | |

| Wastewater discharge per unit of industrial value added (X12) | Wastewater discharge/industrial value added (t/10,000 CNY), − | ||

| SO2 emissions per unit of industrial value added (X13) | SO2 emissions/industrial value added (kg/10,000 CNY), − | ||

| Openness | Import and export development | Foreign trade dependence (X14) | Total import and export/GDP, + |

| Sharing | Infrastructure level | Hospital beds per 10,000 people (X15) | Number of beds/total population (beds per 10,000 persons), + |

| Library collections per 100 people (X16) | Library collections/total population (volumes per 100 persons), + | ||

| Per capita road area (X17) | Road area/total population (m2/person), + | ||

| Education investment level | Education fiscal expenditure intensity (X18) | Education expenditure/total fiscal expenditure (%), + | |

| Income level | Average wage of employed persons (X19) | Average wage of employed persons (CNY), + |

| Criterion Layer | Indicator | Calculation Method and Indicator Direction |

|---|---|---|

| Carrying medium | Water production coefficient (Y1) | Total water resources/precipitation, + |

| Water production modulus (Y2) | Total water resources/land area (104 m3/km2), + | |

| Per capita water resources availability (Y3) | Total water resources/total population (m3/person), + | |

| Utilization | Water use per 10,000 CNY of GDP (Y4) | Total water use/GDP (m3/10,000 CNY), − |

| Agricultural water use (Y5) | Agricultural water use statistics (108 m3), − | |

| Industrial water use (Y6) | Industrial water use statistics (108 m3), − | |

| Domestic water use (Y7) | Domestic water use statistics (108 m3), − | |

| Ecological water use (Y8) | Ecological water use statistics (108 m3), + | |

| Carrying object | Population density (Y9) | Total population/land area (persons/km2), − |

| Proportion of tertiary industry (Y10) | Value added of tertiary industry/GDP (%), + |

| D Value | Type | Subclass Criterion | Coupling Coordination Subclass |

|---|---|---|---|

| [0, 0.5) | Imbalanced Decline | > 0.1 | Imbalanced Decline—lagged type of water resources carrying capacity |

| > 0.1 | Imbalanced Decline—lagged type of high-quality development | ||

| Imbalanced Decline | |||

| [0.5, 0.6) | Barely Coordinated | > 0 | Barely Coordinated—lagged type of water resources carrying capacity |

| > 0.1 | Barely Coordinated—lagged type of high-quality development | ||

| Barely Coordinated | |||

| [0.6, 0.7) | Primary Coordination | > 0 | Primary Coordination—lagged type of water resources carrying capacity |

| > 0.1 | Primary Coordination—lagged type of high-quality development | ||

| Primary Coordination | |||

| [0.7, 0.8) [0.7, 0.8) [0.7, 0.8) | Intermediate Coordination | > 0 | Intermediate Coordination—lagged type of water resources carrying capacity |

| > 0.1 | Intermediate Coordination—lagged type of high-quality development | ||

| Intermediate Coordination | |||

| [0.8, 0.9) | Good Coordination | > 0 | Good Coordination—lagged type of water resources carrying capacity |

| > 0.1 | Good Coordination—lagged type of high-quality development | ||

| Good Coordination | |||

| [0.9, 1.0) | High-Quality Coordination | > 0 | High-Quality Coordination—lagged type of water resources carrying capacity |

| > 0.1 | High-Quality Coordination—lagged type of high-quality development | ||

| High-Quality Coordination |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yu, H.; Wu, J.; Xiao, F.; Shi, L.; Huang, Y. Mechanisms and Empirical Analysis of How New Quality Productive Forces Drive High-Quality Development to Enhance Water Resources Carrying Capacity in the Weihe River Basin. Water 2026, 18, 339. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18030339

Yu H, Wu J, Xiao F, Shi L, Huang Y. Mechanisms and Empirical Analysis of How New Quality Productive Forces Drive High-Quality Development to Enhance Water Resources Carrying Capacity in the Weihe River Basin. Water. 2026; 18(3):339. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18030339

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Haozhe, Jie Wu, Feiyan Xiao, Lei Shi, and Yimin Huang. 2026. "Mechanisms and Empirical Analysis of How New Quality Productive Forces Drive High-Quality Development to Enhance Water Resources Carrying Capacity in the Weihe River Basin" Water 18, no. 3: 339. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18030339

APA StyleYu, H., Wu, J., Xiao, F., Shi, L., & Huang, Y. (2026). Mechanisms and Empirical Analysis of How New Quality Productive Forces Drive High-Quality Development to Enhance Water Resources Carrying Capacity in the Weihe River Basin. Water, 18(3), 339. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18030339