Assessing Economic Vulnerability from Urban Flooding: A Case Study of Catu, a Commerce-Based City in Brazil

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

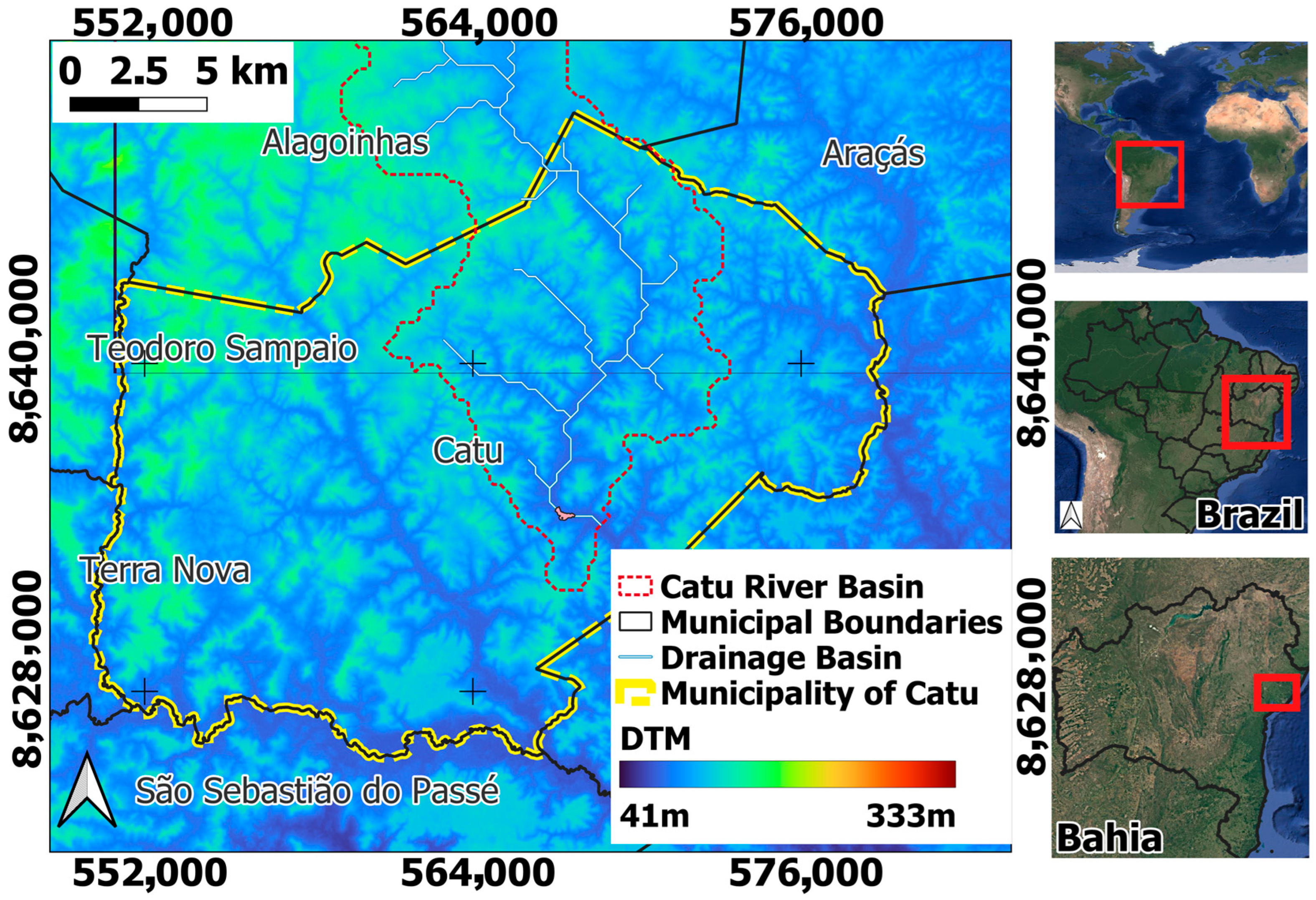

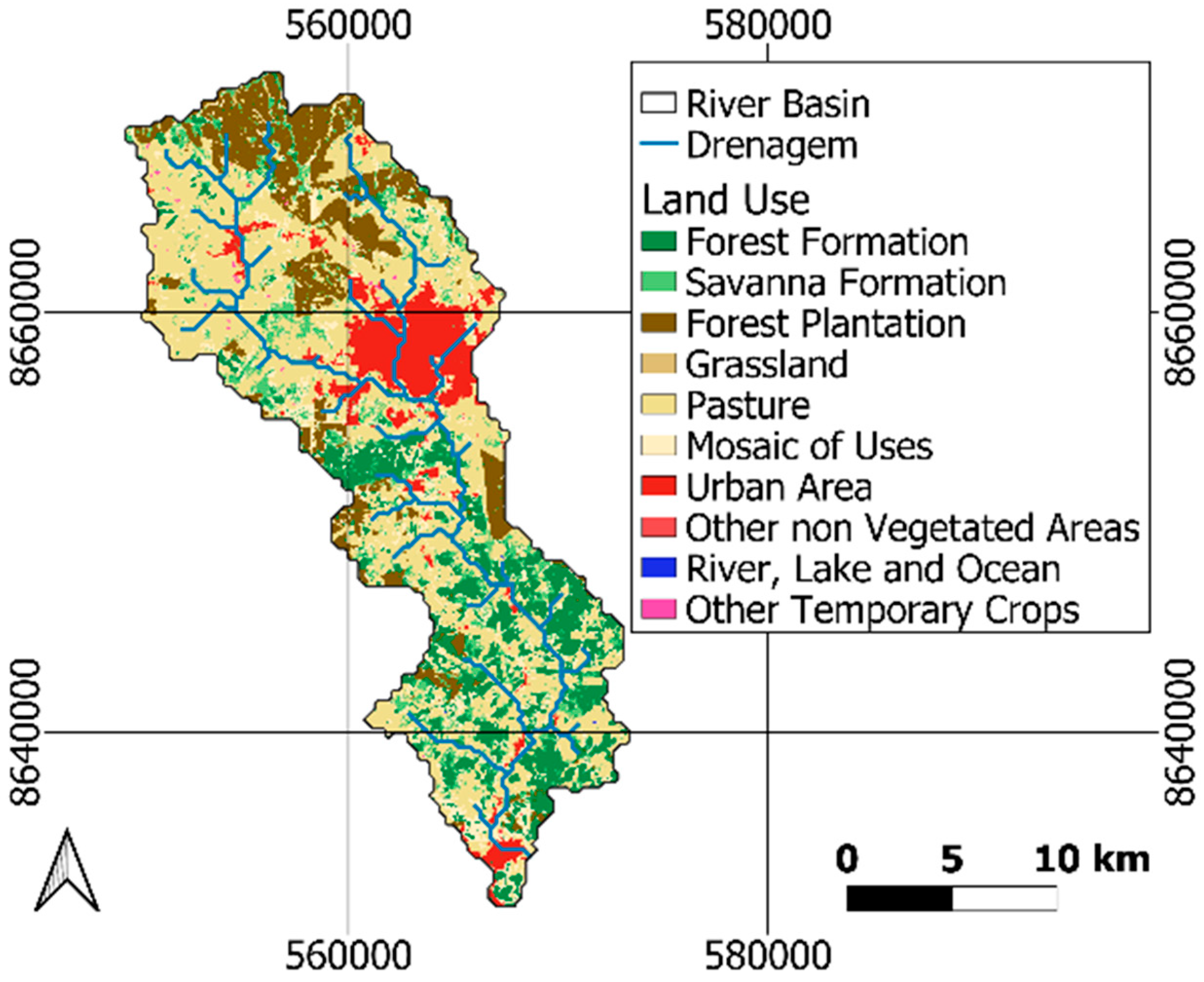

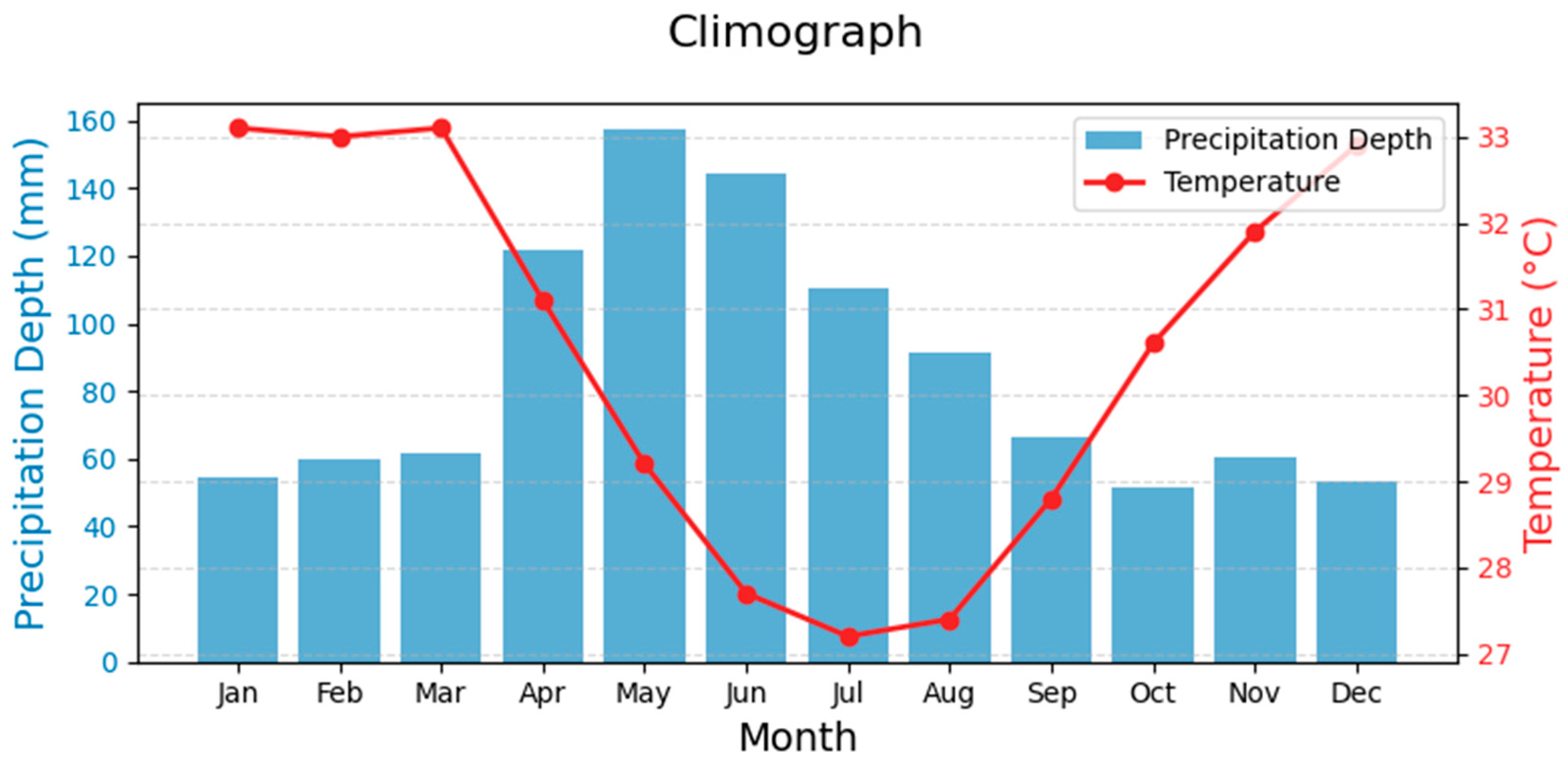

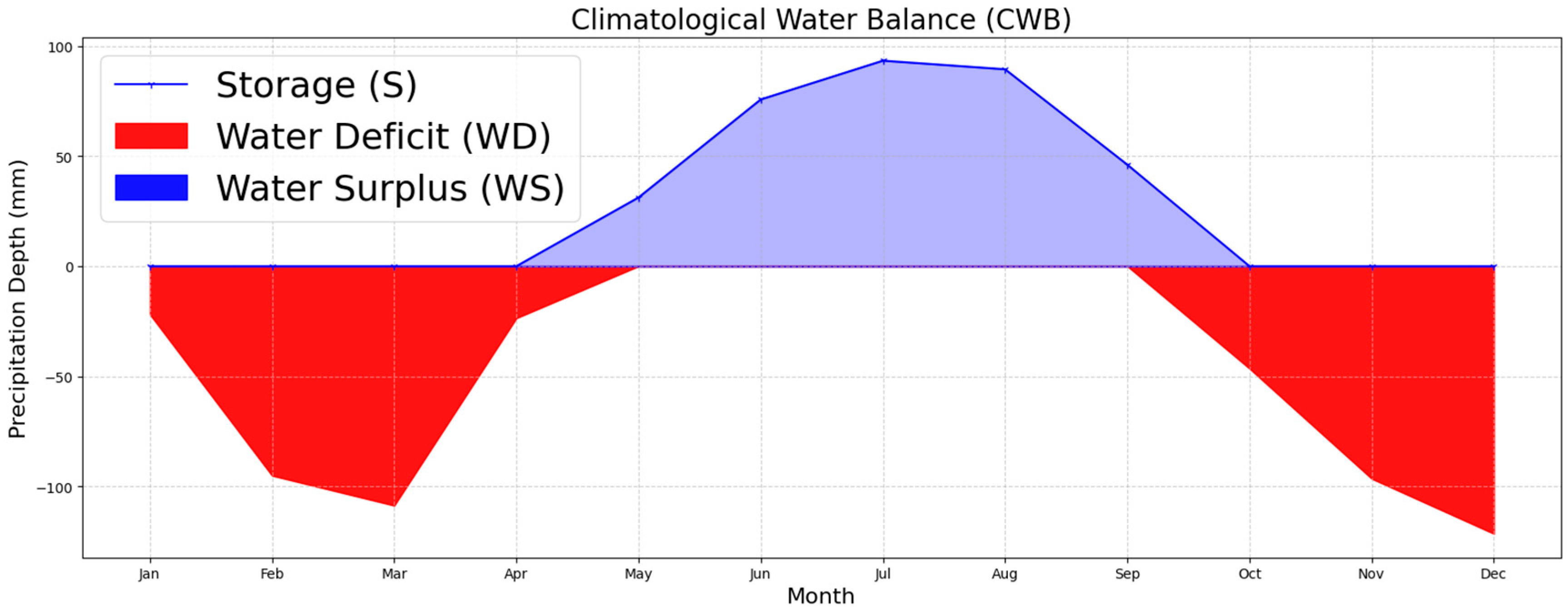

2.2.1. Socio-Environmental Characterization of Catu

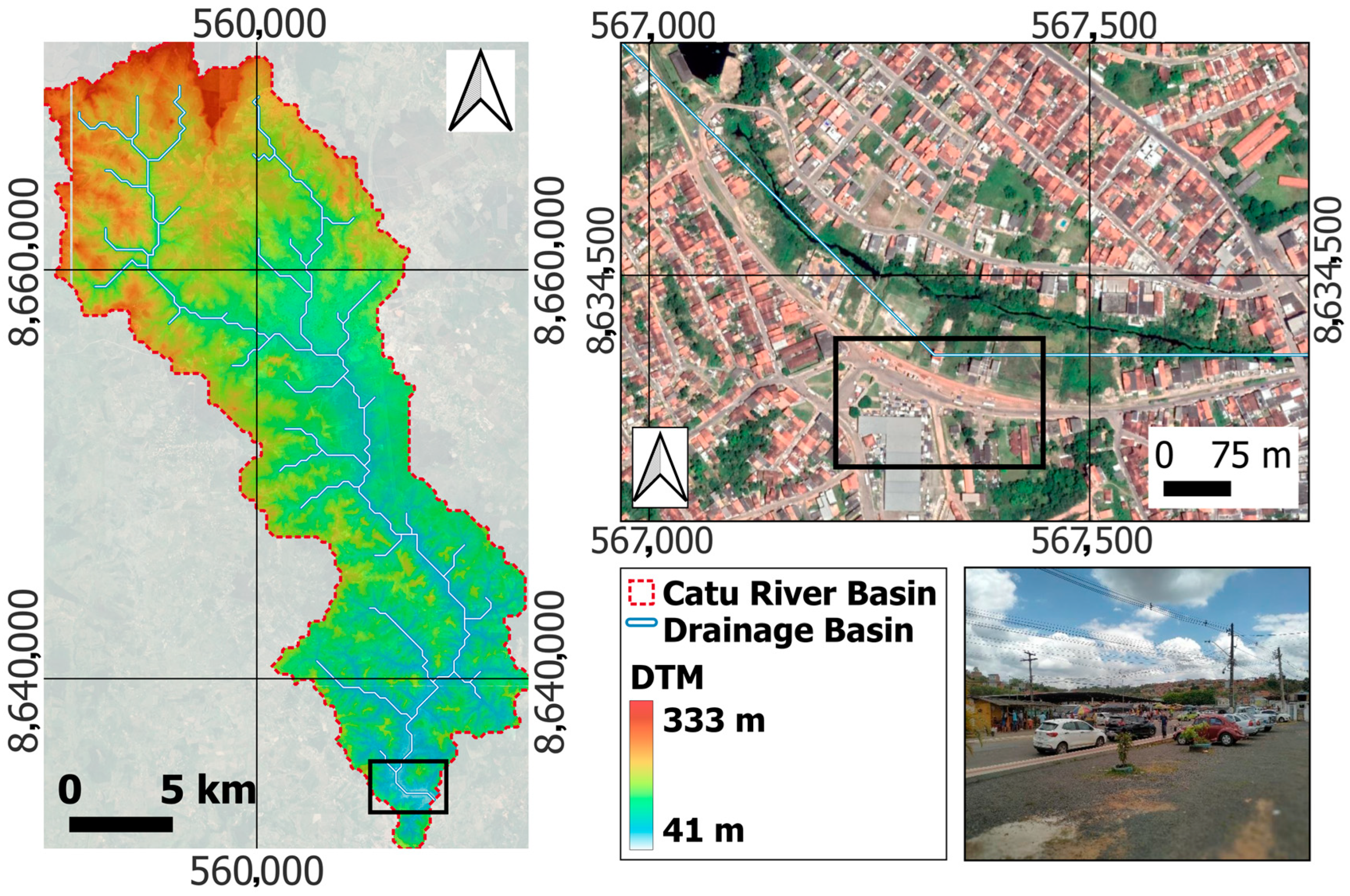

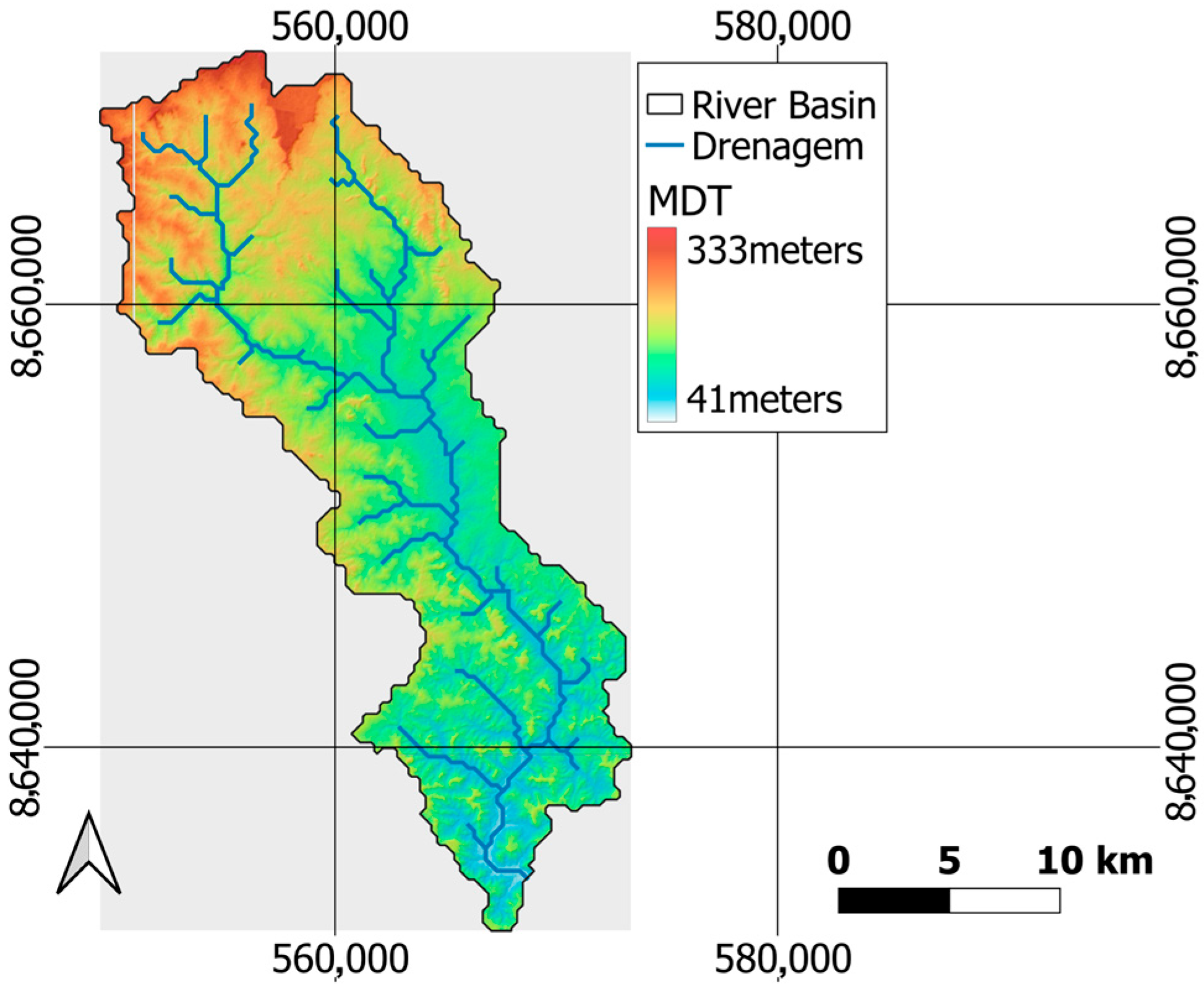

2.2.2. Hydrological Characteristics of the Catu River Basin

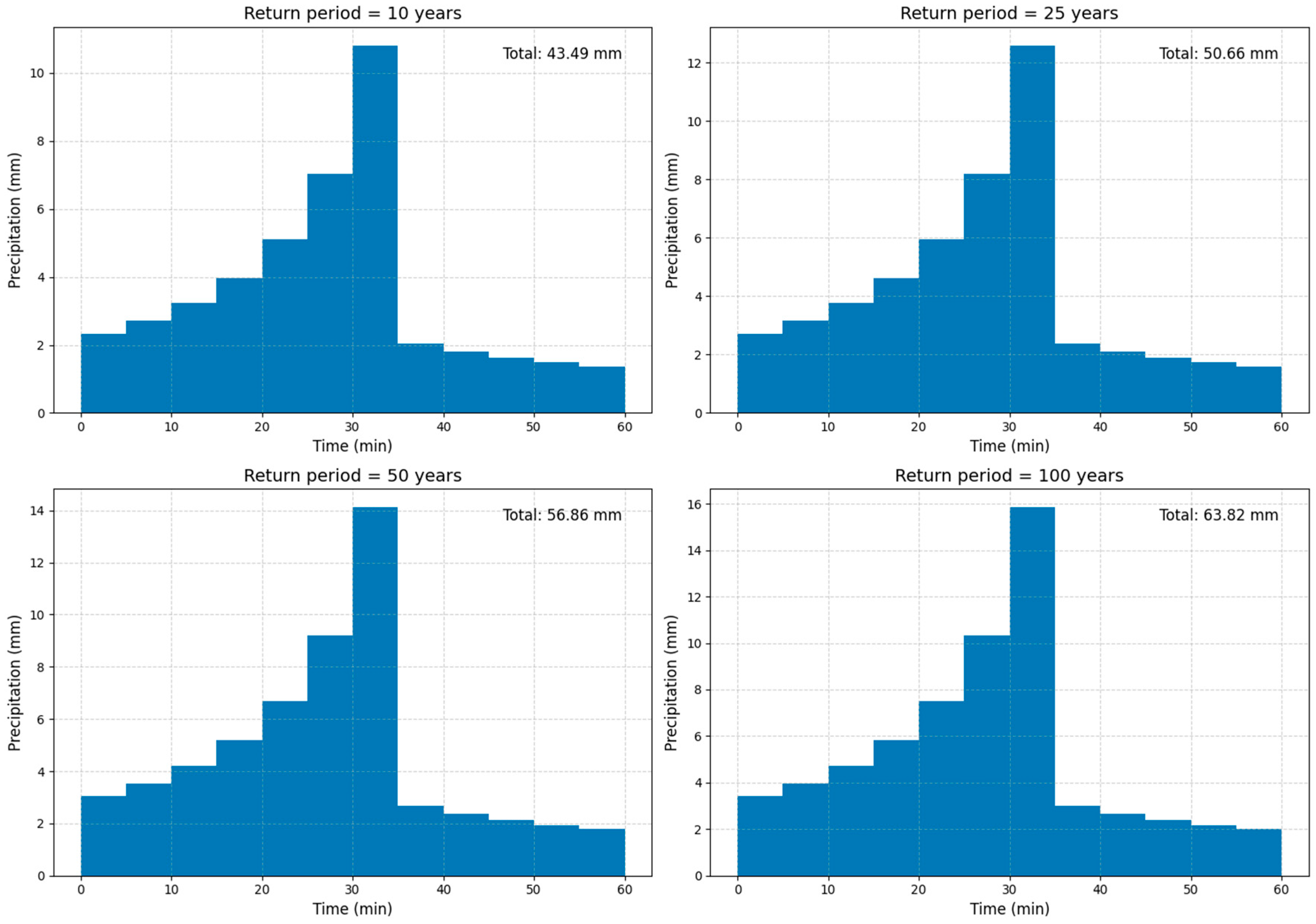

2.2.3. Hyetograph Determination

2.2.4. Methods for Hydrograph Determination

Basin Characterization and Input Data

2.2.5. Hydrological Modeling and Calculation Methods

2.2.6. Hydraulic Modeling for Flood Inundation Simulation

2.3. Quantification of Economic Losses

3. Results and Discussion

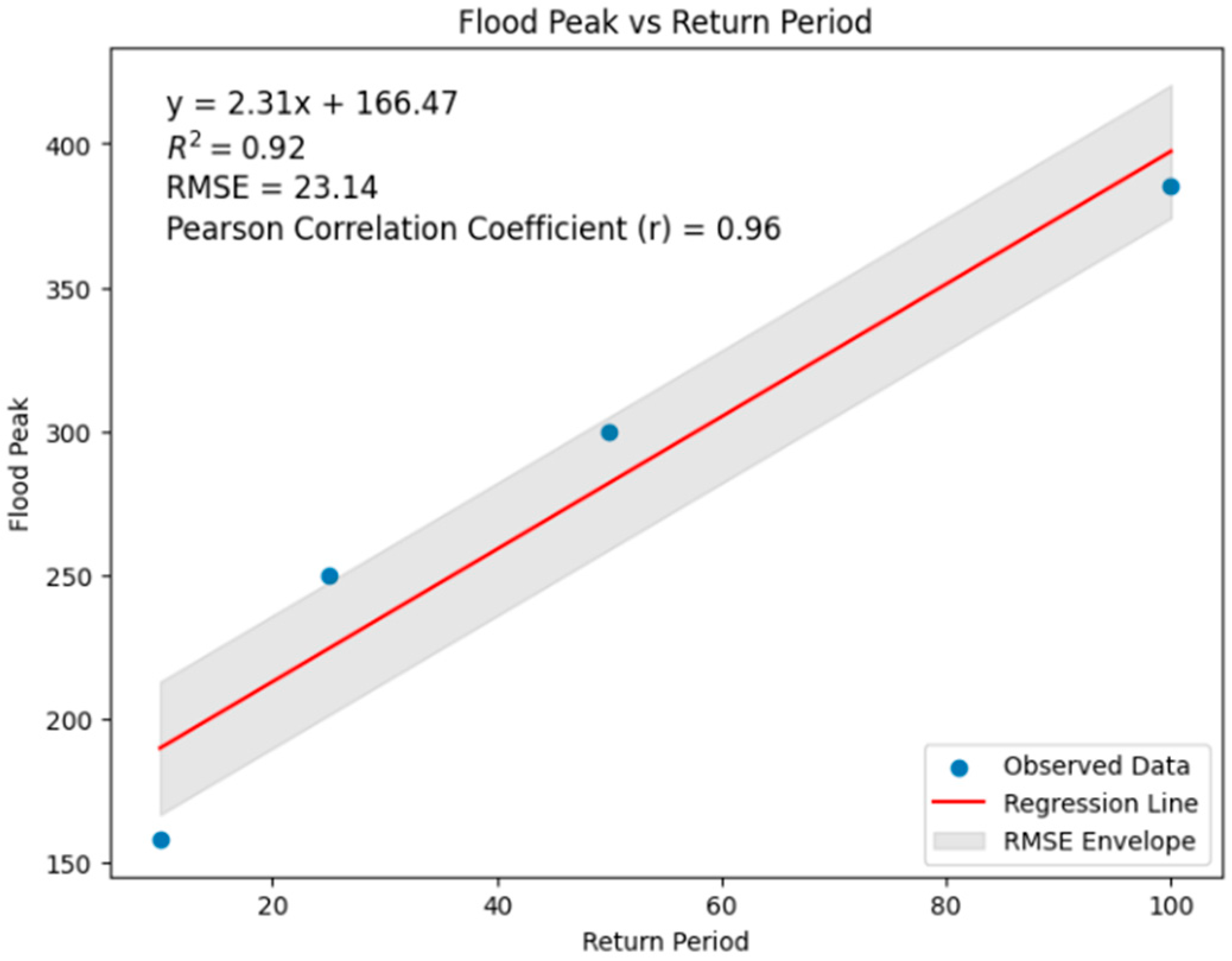

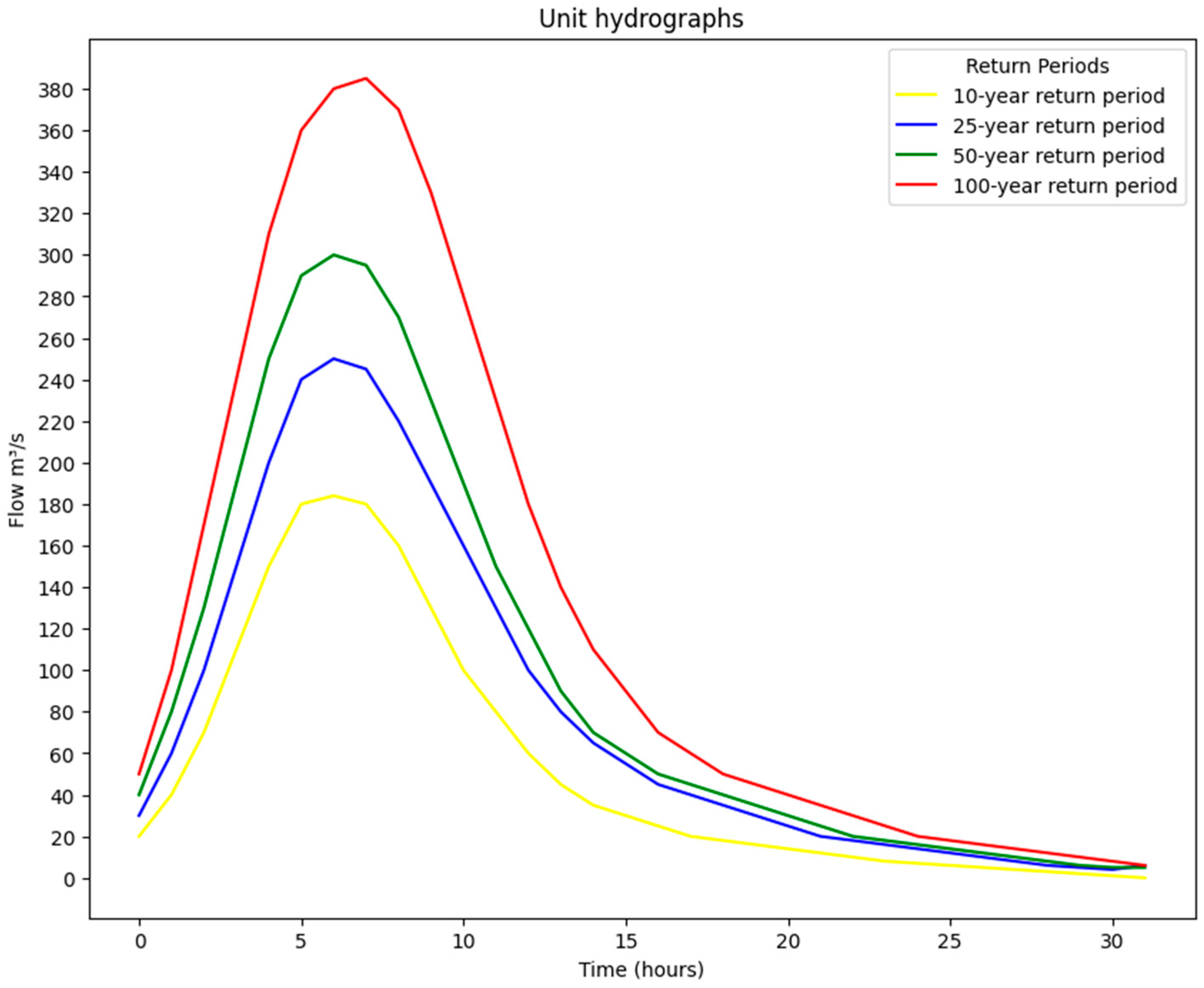

3.1. Flood Peaks

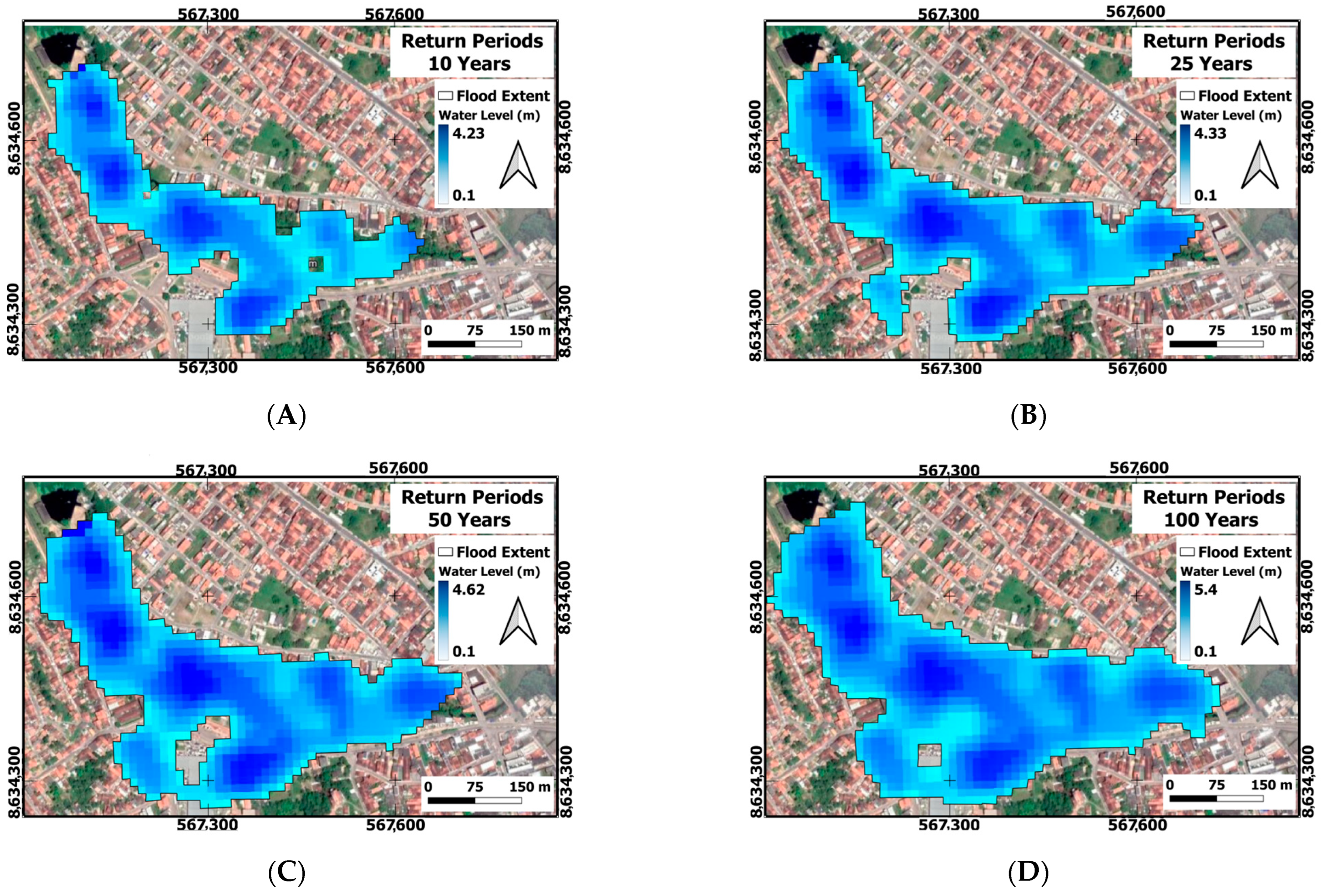

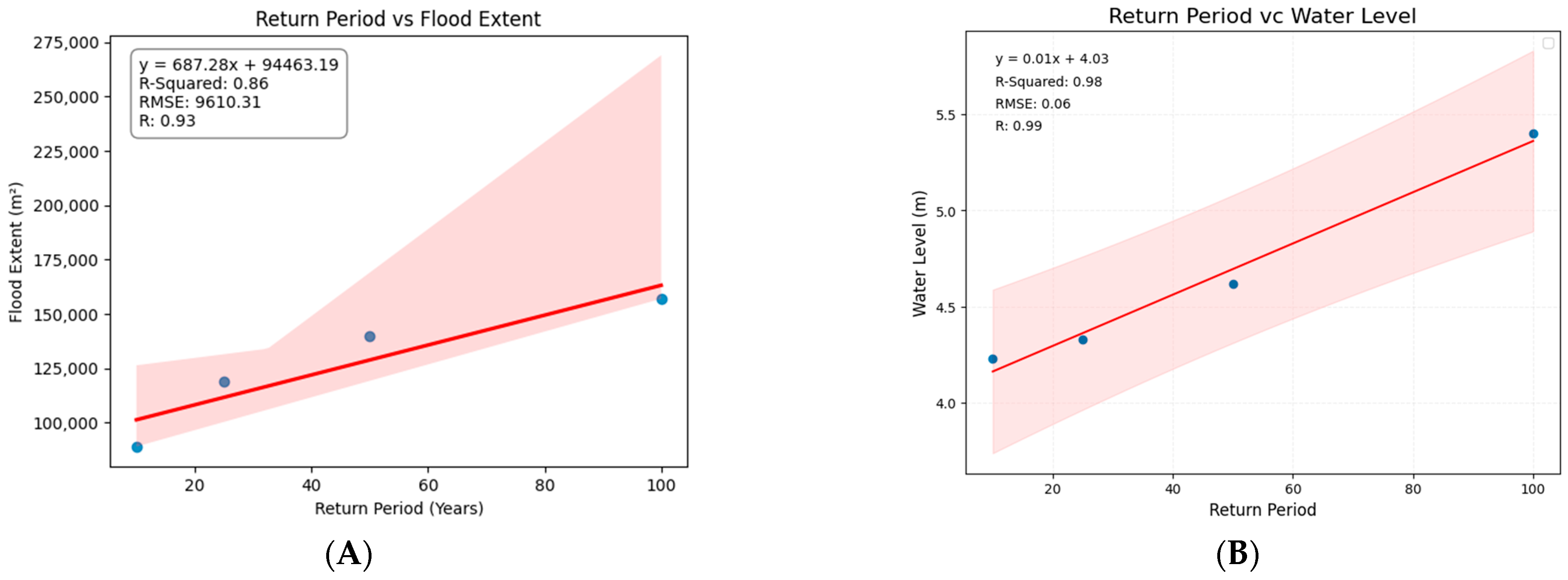

3.2. Flood Inundation Map

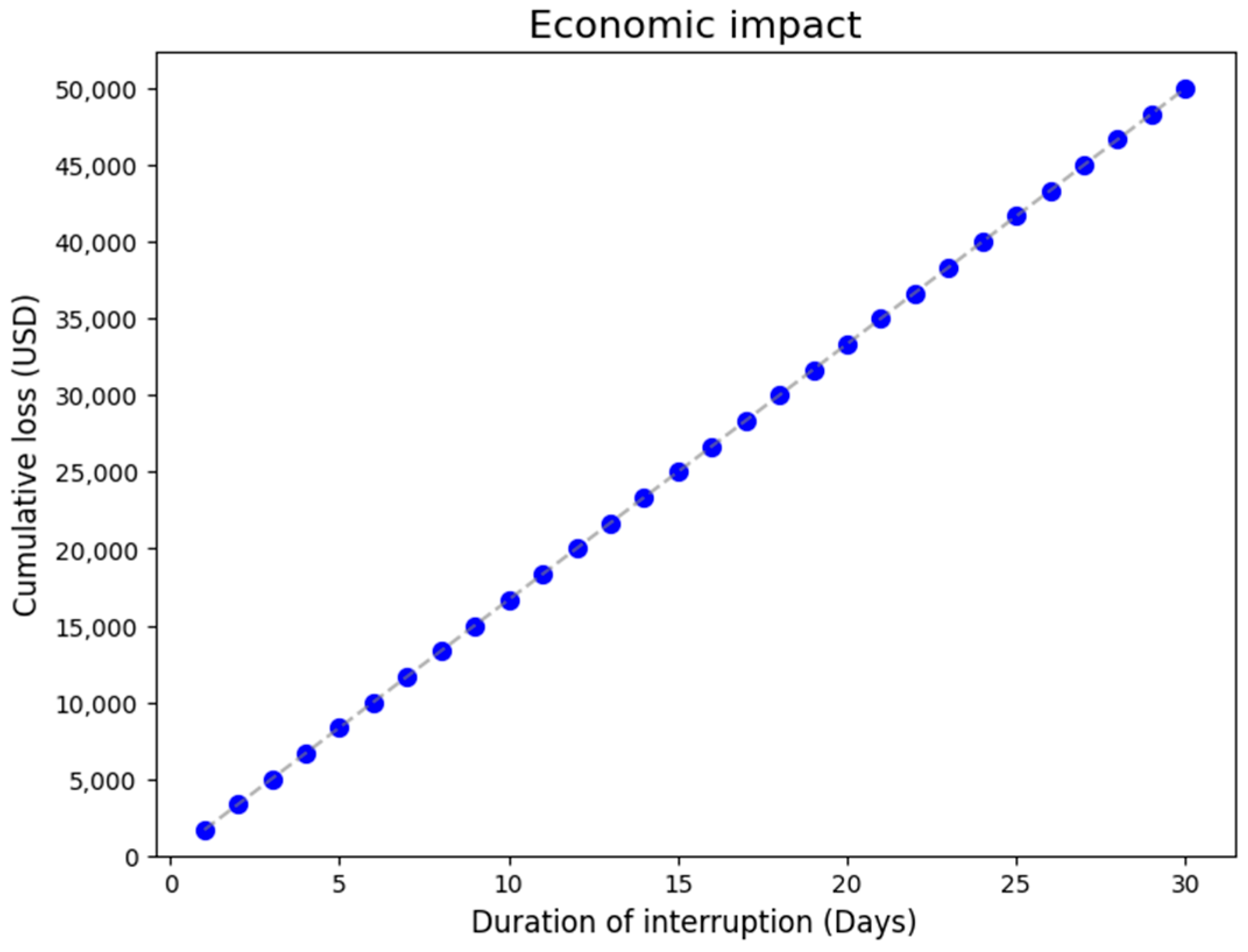

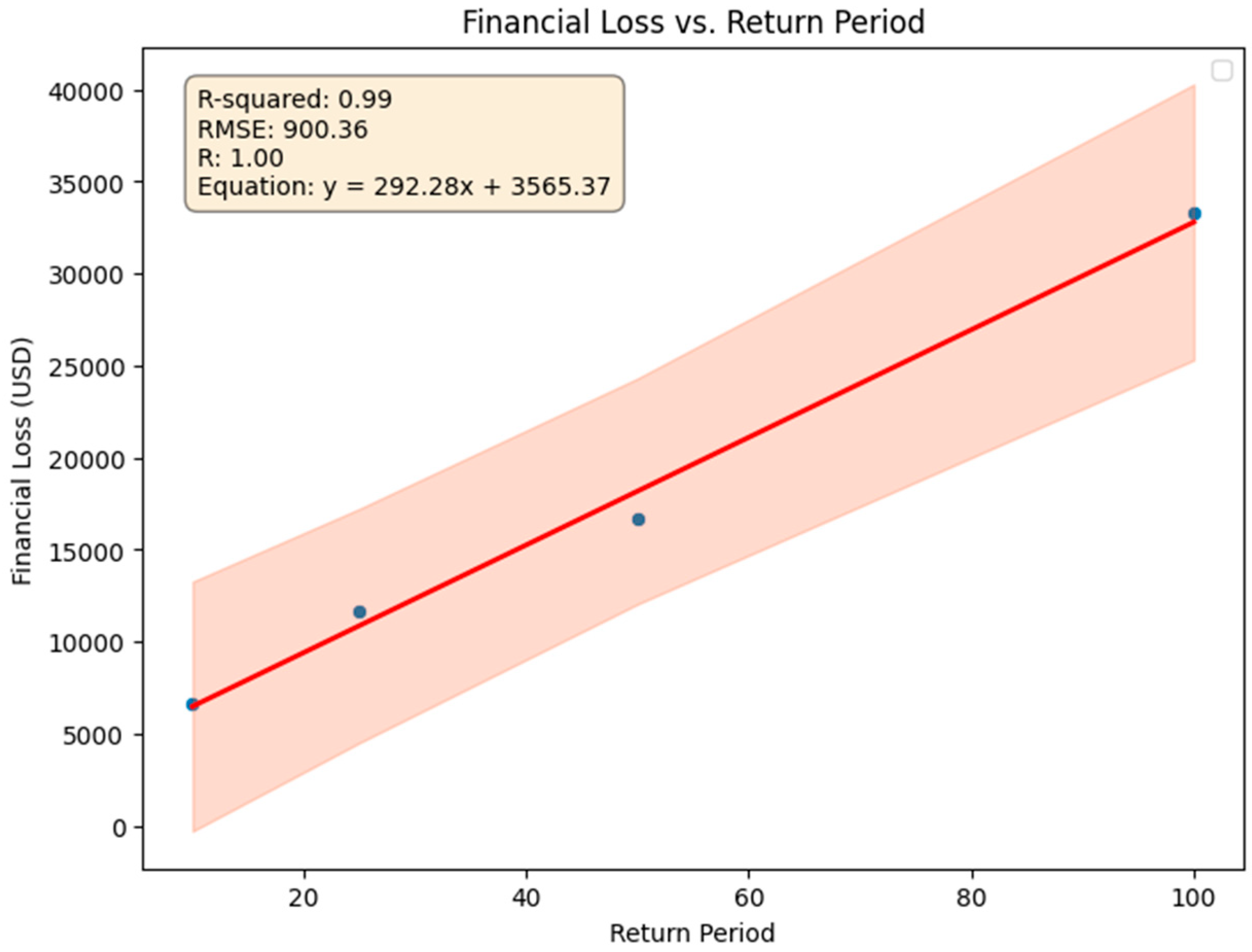

3.3. Economic Loss Model

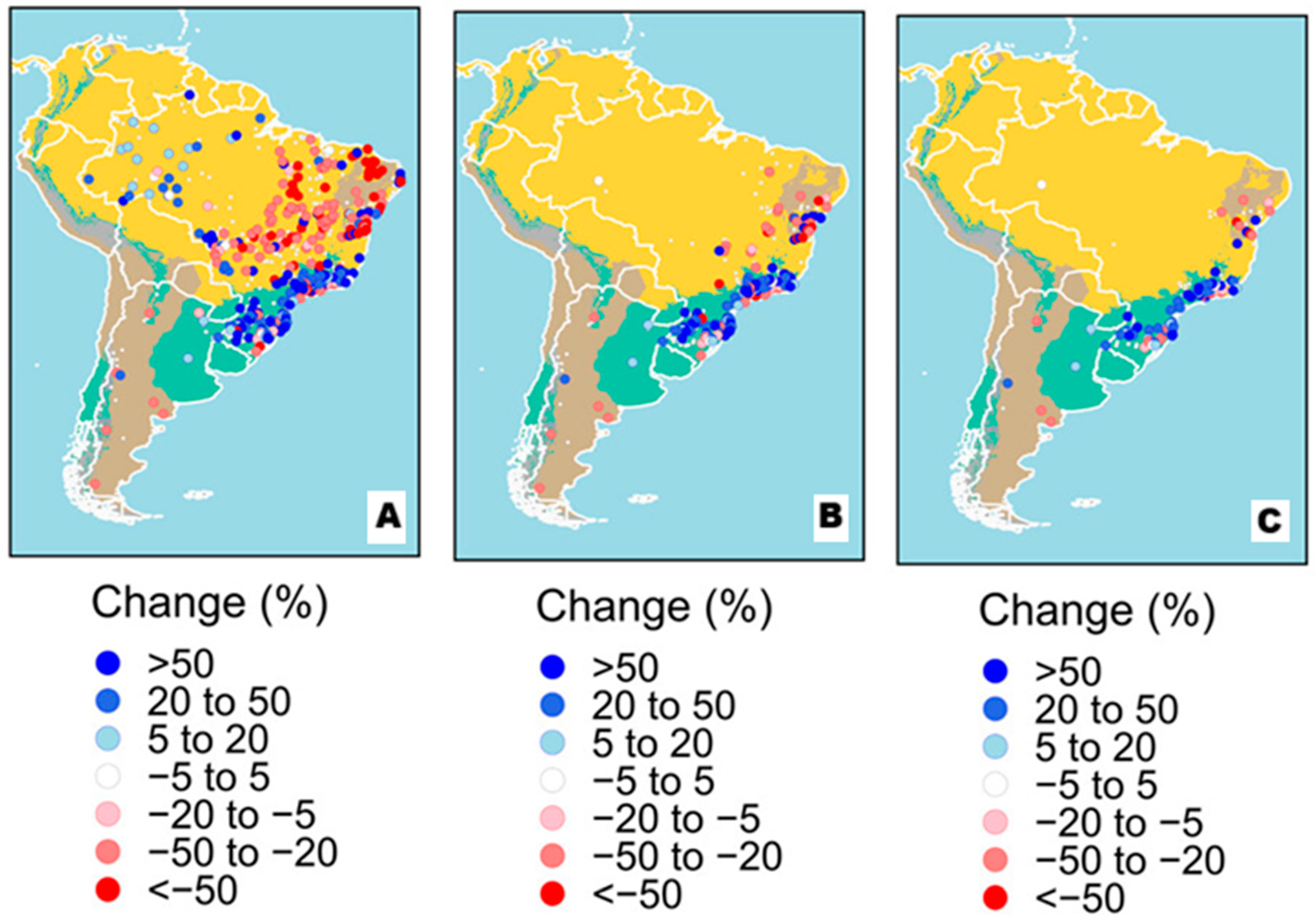

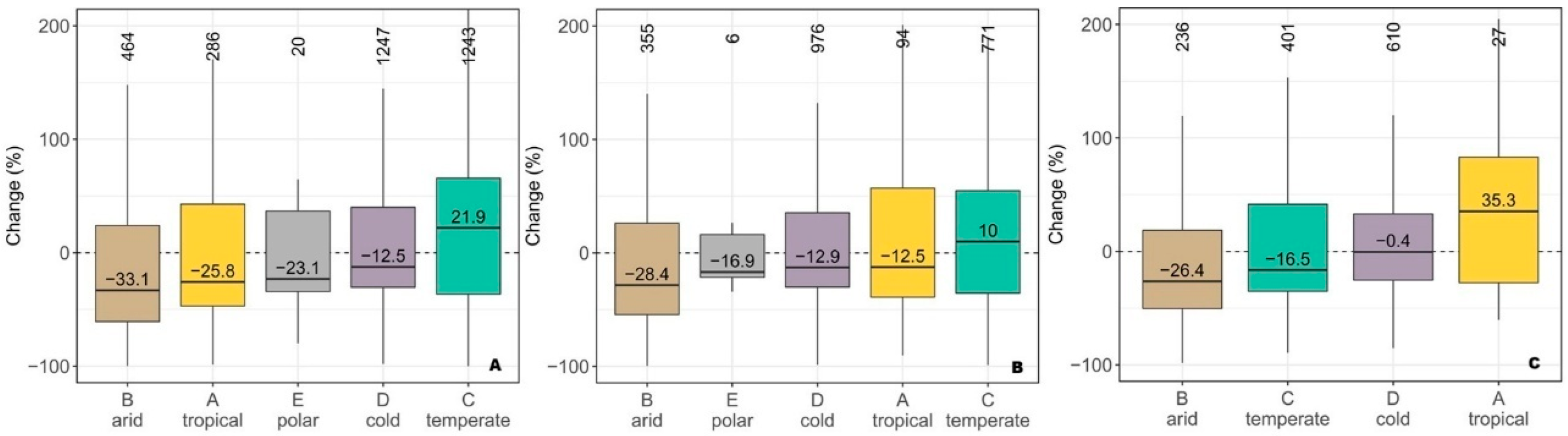

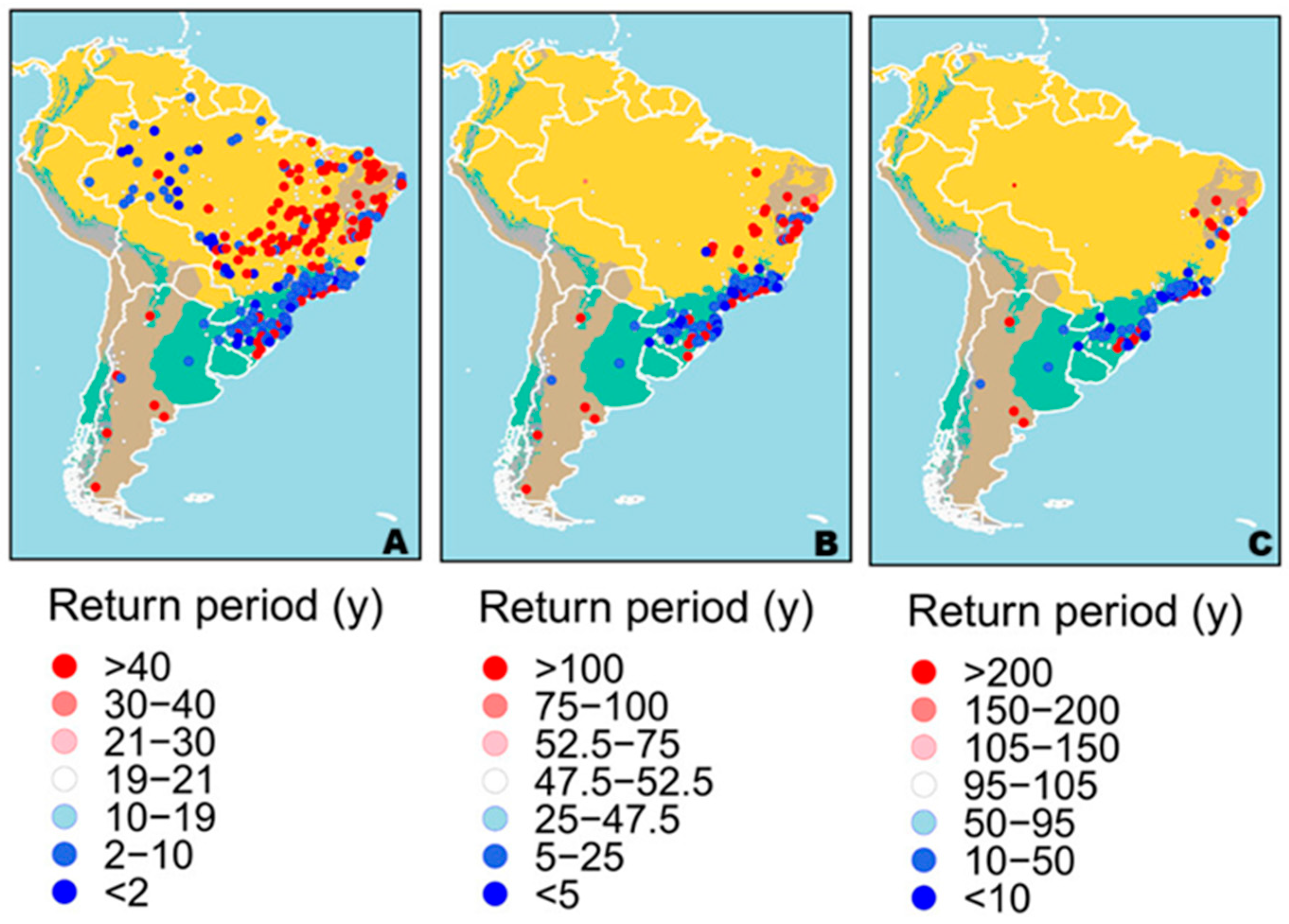

3.4. Climate Change, Return Periods, and Uncertainties

3.5. Climatological Perspective and Economic Impact

4. Conclusions

Limitations and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhu, W.; Wang, S.; Luo, P.; Zha, X.; Cao, Z.; Lyu, J.; Zhou, M.; He, B.; Nover, D. A Quantitative Analysis of the Influence of Temperature Change on the Extreme Precipitation. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, P.J.; Blauhut, V.; Bloemendaal, N.; Daniell, J.E.; de Ruiter, M.C.; Duncan, M.J.; Emberson, R.; Jenkins, S.F.; Kirschbaum, D.; Kunz, M.; et al. Review Article: Natural Hazard Risk Assessments at the Global Scale. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2020, 20, 1069–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CNM. Panorama Desastres Brasil 2013 a 2023; CNM: Brasília, Brazil, 2024; p. 30. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, G.; Li, J.; Feng, P.; Liu, J.; Wang, Y. Impacts of Climate and Land-Use Change on Flood Events with Different Return Periods in a Mountainous Watershed of North China. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2024, 55, 101943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabari, H. Climate Change Impact on Flood and Extreme Precipitation Increases with Water Availability. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 13768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BRASIL Atlas Digital de Desastres no Brasil. Available online: https://app.powerbi.com/view?r=eyJrIjoiYTFkYjk0ZDAtN2NiZi00YWRkLWFlMjItYzllMTY5MDNmYzYyIiwidCI6Ijk2MTFlY2UxLTM0MTQtNGMzNS1hM2YwLTdkMTAwNDI5MGNkNiJ9 (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Hlal, M.; Baraka Munyaka, J.-C.; Chenal, J.; Azmi, R.; Diop, E.B.; Bounabi, M.; Ebnou Abdem, S.A.; Almouctar, M.A.S.; Adraoui, M. Digital Twin Technology for Urban Flood Risk Management: A Systematic Review of Remote Sensing Applications and Early Warning Systems. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Sun, L.; Tian, Z.; Ye, Q.; Wu, S.; Zhang, S. Editorial: Nature-Based Solutions for Urban Water Management. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1228154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, L.; Villarini, G.; Archfield, S.; Faulkner, D.; Lamb, R.; Khouakhi, A.; Yin, J. Global Changes in 20-Year, 50-Year, and 100-Year River Floods. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2021, 48, e2020GL091824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagras, A. Modeling of Rainfall-Runoff and Flooding Using HEC-HMS Model through GIS in an Arid Environment: A Case Study in the Safaga Valley Basin, West Safaga City, Egypt. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 2026, 233, 105867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halwatura, D.; Najim, M.M.M. Application of the HEC-HMS Model for Runoff Simulation in a Tropical Catchment. Environ. Model. Softw. 2013, 46, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Martínez, M.; Osornio Berthet, L.J.; Meléndez Estrada, J.; Cruz Castro, O. Identification of Flood-Prone Areas Using the HEC-RAS 2D Model in a Region of the Valley of Mexico. Chemosphere 2025, 386, 144609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- JAXA ASF Data Search. Available online: https://search.asf.alaska.edu/#/ (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- MapBiomas Project Collection 10 of Annual Land Use and Land Cover Maps of Brazil. Available online: https://plataforma.brasil.mapbiomas.org/ (accessed on 27 August 2025).

- INMET Instituto Nacional de Meteorologia—INMET. Available online: https://portal.inmet.gov.br/normais (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- IBGE. Censo Demográfico. Available online: https://cidades.ibge.gov.br/brasil/ba/catu/panorama (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- SEBRAE Catu: Emprego, Ocupações, Empresas, Dados Demográficos e Educação. Observatório DataMPE Brasil. Available online: https://datampe.sebrae.com.br/profile/geo/catu (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- EITA; FUNASA; UFMG. Início. Available online: https://infosanbas.org.br/ (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- PNUD. Atlas Do Desenvolvimento Humano No Brasil. Available online: http://www.atlasbrasil.org.br/consulta/map (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- Menezes, M.A.D.A. Educação Profissional, Agricultura Familiar e Desenvolvimento Local e Regional: O Instituto Federal de Educação Baiano Campus Catu; Universidade Salvador: Salvador, Brazil, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira, A.M.; Barros de Matos, M.R.; Figueiredo, M.B.; de Oliveira, L.N.A. The Importance of Dunnian Runoff in Atlantic Forest Remnants: An Integrated Analysis Between Machine Learning and Spectral Indices. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 3977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, H.E.; Zimmermann, N.E.; McVicar, T.R.; Vergopolan, N.; Berg, A.; Wood, E.F. Present and Future Köppen-Geiger Climate Classification Maps at 1-Km Resolution. Sci. Data 2018, 5, 180214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, P.G. Estudo Hidroquímico das Águas Subterrâneas do Município de Catu-Bahia Universidade Federal da Bahia Instituto de Geociências Departamento de Geologia; Universidade Federal da Bahia: Salvador, Brazil, 2015; Available online: https://nehma.ufba.br/sites/nehma.ufba.br/files/PEDRO_2015_1.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Santana, L.D.N. Modelagem Econômica do Potencial Destrutivo em Decorrência dos Eventos Extremos de Chuvas Universidade do Estado da Bahia Departamento de Ciências Extas e da Terrda Programa de Pós-Graduação em Modelagem e Simulação de Biossistemas. Master’s Thesis, Universidade do Estado da Bahia, Alagoinhas, Brazil, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva, M.S.L.; de Oliveira Neto, M.B. Latossolos Amarelos—Portal Embrapa. Available online: https://www.embrapa.br/agencia-de-informacao-tecnologica/territorios/territorio-mata-sul-pernambucana/caracteristicas-do-territorio/recursos-naturais/solos/latossolos-amarelos (accessed on 5 April 2024).

- de Lima Sebadelhe Valério, E.; Fontes, A.S.; Goldenfum, J.A.; Monte, B.E.O. Avaliação dos Efeitos de Mudanças Climáticas na Bacia do rio Catu-BA. In Proceedings of the XXI SBRH—Simpósio Brasileiro de Recursos Hídricos, Brasília, Brazil, 22 November 2015; Volume 1, pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- de Jesus Porciúncula, R.; de Lima, O.A.L.; Leal, L.R.B. Método Geoelétrico—Potencial Instrumento Para Auxílio da Gestão do Solo e Dos Recursos Hídricos Subterrâneos: Estudos de Caso, Alagoinhas, Bahia. Águas Subterrâneas 2016. Available online: https://aguassubterraneas.abas.org/asubterraneas/article/view/28709 (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Agakpe, M.D.; Nyatuame, M.; Ampiaw, F. Development of Intensity—Duration—Frequency Curves Using Combined Rain Gauge and Remote Sense Datasets for Weta Traditional Area in Ghana. HydroResearch 2024, 7, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, A.d.G.; de Souza Neto, I.R.; Costa, V.A.F.; Mendes, L.A. Assessing Intensity-Duration-Frequency Equations and Spatialization Techniques across the Grande River Basin in the State of Bahia, Brazil. RBRH 2022, 27, e43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar-González, D.; Singaña-Chasi, M.S.; González-Vergara, J.; Erazo, B.; Zambrano, M.; Acosta, D.; Villacís, M.; Guallpa, M.; Lahuatte, B.; Peluffo-Ordóñez, D.H. Intensity-Duration-Frequency Curve for Extreme Rainfall Event Characterization, in the High Tropical Andes. Water 2022, 14, 2998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsoyiannis, D.; Kozonis, D.; Manetas, A. A Mathematical Framework for Studying Rainfall Intensity-Duration-Frequency Relationships. J. Hydrol. 1998, 206, 118–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, P.G.; da Silva, J.B.L.; Bento, N.L.; da Silva, D.P.; de Souza, B.S. Estimativa dos Parâmetros de Equações de Intensidade-Duração-Frequência de Chuvas Intensas para o Estado da Bahia, Brasil. REDE Rev. Eletrônica PRODEMA 2021, 1, 151–164. [Google Scholar]

- de Abreu, F.G.; Sobrinha, L.A.; Brandão, J.L.B. Análise da distribuição temporal das chuvas em eventos hidrológicos extremos. Eng. Sanit. Ambient. 2017, 22, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, J.F.M. Acidentes na Indústria de Petróleo e Seus Impactos na Segurança Operacional e Preservação Ambiental; Universidade Federal Fluminense: Niteroi, Brazil, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- dos Santos, H.G.; Jacomine, P.K.T.; dos Anjos, L.H.C.; de Oliveira, V.Á.; Lumbreras, J.F.; Coelho, M.R.; de Almeida, J.A.; de Araújo Filho, J.C.; Lima, H.N.; Marques, F.A.; et al. Sistema Brasileiro de Classificação de Solos, 6th ed.; Embrapa: Brasília, Brazil, 2025; ISBN 978-65-5467-104-0. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Army Corps of Engineers; Hydrologic Engineering Center. HEC Newsletter, Spring 2008; U.S. Army Corps of Engineers: Davis, CA, USA, 2008. Available online: https://www.hec.usace.army.mil/newsletters/HEC_Newsletter_Spring2008.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Durán-Barroso, P.; González, J.; Valdés, J.B. Improvement of the Integration of Soil Moisture Accounting into the NRCS-CN Model. J. Hydrol. 2016, 542, 809–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.; Singh, P.K.; Mishra, S.K.; Singh, V.P.; Singh, V.; Singh, A. Activation Soil Moisture Accounting (ASMA) for Runoff Estimation Using Soil Conservation Service Curve Number (SCS-CN) Method. J. Hydrol. 2020, 589, 125114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Li, F.; Li, J.; Xing, J.; Yang, J.; Guo, J.; Du, S. Recognition of land use on open-pit coal mining area based on DeepLabv3+ and GF-2 high-resolution images based on DeepLabv3+and GF-2 Land use classification of open-pit coal mining areas based on high-resolution imagery. Meitiandizhi Yu Kantan/Coal Geol. Explor. 2022, 50, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.K.; Singh, V.P. SCS-CN Method. In Soil Conservation Service Curve Number (SCS-CN) Methodology; Mishra, S.K., Singh, V.P., Eds.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 84–146. ISBN 978-94-017-0147-1. [Google Scholar]

- Khattab, M.I.; Fadl, M.E.; Megahed, H.A.; Saleem, A.M.; El-Saadawy, O.; Drosos, M.; Scopa, A.; Selim, M.K. Evaluation of the Soil Conservation Service Curve Number (SCS-CN) Method for Flash Flood Runoff Estimation in Arid Regions: A Case Study of Central Eastern Desert, Egypt. Hydrology 2025, 12, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Farias Júnior, J.E.F. Análise Comparativa Do Tempo de Concentração: Um Estudo de Caso Na Bacia Do Rio Cônego, Município de Nova Friburgo/RJ. In Proceedings of the XIX Simpósio Brasileiro de Recursos Hídricos, Maceió, Brazil, 27 November 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Zolghadr, M.; Rafiee, M.R.; Esmaeilmanesh, F.; Fathi, A.; Tripathi, R.P.; Rathnayake, U.; Gunakala, S.R.; Azamathulla, H.M. Computation of Time of Concentration Based on Two-Dimensional Hydraulic Simulation. Water 2022, 14, 3155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temez, J.R. Cálculo Hidrometeorológico de Caudales Máximos en Peaueñas Cuencas Naturales, Direccion General de Carreteras, 12th ed.; Ministério de Obras Publicas y Urbanismo (MOPU): Madrid, Spain, 1978; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Farid, M.; Dewi, N.T.; Adityawan, M.B.; Nugroho, E.O.; Alhamid, A.K.; Wahid, A.N.; Sihombing, Y.I. Probabilistic Urban Flood Risk Assessment of Multi-Sectoral Economic Losses Due to Levee Overtopping. Results Eng. 2025, 27, 106260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, E. Determinação da Cota de Inundação Severa com Base no Critério de Prejuízos Econômicos Associados: Aplicação ao Município de São Sebastião do Caí—RS. In Proceedings of the XXIV SBRH—Simpósio Brasileiro de Recursos Hídricos, Belo Horizonte, Brazil, 21 November 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Tachini, M. Avaliação de Danos Associados às Inundações No Município de Blumenau. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Florianópolis, Brazil, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Boers, N.; Goswami, B.; Rheinwalt, A.; Bookhagen, B.; Hoskins, B.; Kurths, J. Complex Networks Reveal Global Pattern of Extreme-Rainfall Teleconnections. Nature 2019, 566, 373–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Guo, L.; Sha, Y.; Yang, K. Knowledge Map and Global Trends in Extreme Weather Research from 1980 to 2019: A Bibliometric Analysis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 49755–49773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nhamo, G.; Chapungu, L.; Mutanda, G.W. Trends and Impacts of Climate-Induced Extreme Weather Events in South Africa (1920–2023). Environ. Dev. 2025, 55, 101183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villasante, A.; Fernández-Serrano, Á.; Osuna-Sequera, C.; Hermoso, E. Methodology for Stiffness Prediction in Structural Timber Using Cross-Validation RMSE Analysis. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 107, 112767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, G.; Gomez-Velez, J.D.; Chen, X.; Scheibe, T. The Directional Unit Hydrograph Model: Connecting Streamflow Response to Storm Dynamics. J. Hydrol. 2023, 627, 130422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, S.-S.; Hsu, Y.-W. Unit Hydrographs for Estimating Surface Runoff and Refining the Water Budget Model of a Mountain Wetland. Ecol. Eng. 2021, 173, 106435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, H.-H.; Lee, H.; Thuy Du, T.L.; Rostami, A.; Chang, C.-H.; Markert, K.N.; Nelson, E.J.; Williams, G.P.; Li, S.; Straka, W.; et al. An Interpretable and Scalable Model for Rapid Flood Extent Forecasting Using Satellite Imagery and Machine Learning with Rotated EOF Analysis. Environ. Model. Softw. 2025, 192, 106562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malla, S.; Ohgushi, K. Evaluation of Climate Change Impact on Future Flood in the Bagmati River Basin, Nepal Using CMIP6 Climate Projections and HEC-RAS Modeling. Water Cycle 2026, 7, 164–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barna, D.M.; Engeland, K.; Thorarinsdottir, T.L.; Xu, C.-Y. Flexible and Consistent Flood–Duration–Frequency Modeling: A Bayesian Approach. J. Hydrol. 2023, 620, 129448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, D.L.J.; Tropsha, A.; Winkler, D.A. Beware of R2: Simple, Unambiguous Assessment of the Prediction Accuracy of QSAR and QSPR Models. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2015, 55, 1316–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curt, C. Multirisk: What Trends in Recent Works?—A Bibliometric Analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 763, 142951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gill, J.C.; Duncan, M.; Ciurean, R.; Smale, L.; Stuparu, D.; Schlumberger, J.; de Ruiter, M.; Tiggeloven, T.; Torresan, S.; Gottardo, S.; et al. Handbook of Multi-Hazard, Multi-Risk Definitions and Concepts; British Geological Survey: Keyworth, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Tilloy, A.; Malamud, B.D.; Winter, H.; Joly-Laugel, A. A Review of Quantification Methodologies for Multi-Hazard Interrelationships. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2019, 196, 102881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBGE. Available online: https://www.ibge.gov.br/cidades-e-estados/ba/catu.html (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Dutta, D.; Herath, S.; Musiake, K. A Mathematical Model for Flood Loss Estimation. J. Hydrol. 2003, 277, 24–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Jung, K. Economic Assessment of Flood Damage in South Korea: An Object-Based Comparative Study of National and Local Rivers. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2026, 116, 108121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D.K.; Chatterjee, M.; Kaur, G.; Vavilala, S. Deep Learning Applications for Disease Diagnosis. In Deep Learning for Medical Applications with Unique Data; Gupta, D., Kose, U., Khanna, A., Balas, V.E., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; pp. 31–51. ISBN 978-0-12-824145-5. [Google Scholar]

- Pleninger, R. Impact of Natural Disasters on the Income Distribution. World Dev. 2022, 157, 105936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, P. The Hole Dug Deeper: Flash Floods, Income Disparities, and Labor Informality in Brazil. Ecol. Econ. 2025, 237, 108689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Summary for Policymakers. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/syr/summary-for-policymakers (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Ganaie, D.B.; Sajjad, H.; Ali, R.; Sharma, A.; Rahaman, M.H.; Masroor, M. Climate Change Induced Storm Surge Flood: A Systematic Review for Future Research Progression. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2025, 89, 104374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, A.; Dayem, A. Tropical Cyclone Risk Mapping for a Coastal City Using Geospatial Techniques. J. Coast. Conserv. 2021, 25, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narimani, R.; Jun, C.; Shahzad, S.; Oh, J.; Park, K. Application of a Novel Hybrid Method for Flood Susceptibility Mapping with Satellite Images: A Case Study of Seoul, Korea. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayo, T.L.; Lin, N. Climate Change Impacts to the Coastal Flood Hazard in the Northeastern United States. Weather. Clim. Extrem. 2022, 36, 100453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzke, C.L.E. Changing Temporal Volatility of Precipitation Extremes Due to Global Warming. Int. J. Climatol. 2022, 42, 8971–8983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, L.J.; Villarini, G. Recent Trends in U.S. Flood Risk. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2016, 43, 12428–12436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasko, C.; Nathan, R. Influence of Changes in Rainfall and Soil Moisture on Trends in Flooding. J. Hydrol. 2019, 575, 432–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodell, M.; Famiglietti, J.S.; Wiese, D.N.; Reager, J.T.; Beaudoing, H.K.; Landerer, F.W.; Lo, M.-H. Emerging Trends in Global Freshwater Availability. Nature 2018, 557, 651–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Land Use | Area (km2) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Grassland | 0.031 | 0.07 |

| Water | 0.091 | 0.023 |

| Other non-Vegetated Area | 0.238 | 0.061 |

| Other Temporary Crops | 0.630 | 0.161 |

| Savanna Formation | 34.573 | 8.864 |

| Urban Area | 35.212 | 9.028 |

| Mosaic of Uses | 47.028 | 12.058 |

| Forest Plantation | 51.825 | 13.287 |

| Forest Formation | 61.198 | 15.697 |

| Pasture | 159.188 | 40.815 |

| Basin Physical Characteristics | Sub-Basins | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| SUB1 | SUB2 | SUB3 | |

| Total Area (km2) | 118.75 | 83.21 | 189.62 |

| Main River Length (km) | 23.45 | 16.42 | 29.76 |

| Maximum Elevation (m) | 330.00 | 245 | 111 |

| Minimum Elevation (m) | 112.00 | 108 | 58 |

| Elevation Difference (m) | 218.00 | 137 | 53 |

| Slope (%) | 0.009296375 | 0.008343484 | 0.001780914 |

| Time of Concentration (h) | 8.025095802 | 6.248112522 | 13.16619006 |

| Lag Time (h) | 4.815057481 | 3.748867513 | 7.899714036 |

| Class | Area (m2) | Area (km2) | CN | A × CN |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water | 101.44 | 0.101436 | 100 | 10.1436 |

| Urban Area | 27,546.83 | 27.546828 | 90 | 2479.21452 |

| Agriculture | 283,319.80 | 283.319799 | 78 | 22,098.9443 |

| Dense Vegetation | 78,534.90 | 78.534903 | 70 | 5497.44321 |

| Low Vegetation | 500.19 | 0.500193 | 75 | 37.514475 |

| Total | 390,003.16 | 390.00 | 30,123.26 | |

| Weighted CN | 77.2385029 | |||

| Return Period | Flood Peak (m3/s) |

|---|---|

| 10 | 158 |

| 25 | 250 |

| 50 | 300 |

| 100 | 385 |

| Return Period | Inundated Area (m2) | Area Variation (%) | Total Depth (m) | Depth Variation (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 89,000 | - | 4.23 | - |

| 25 | 119,000 | 33.70% | 4.33 | 2.40% |

| 50 | 140,000 | 17.60% | 4.62 | 6.70% |

| 100 | 157,000 | 12.10% | 5.4 | 16.90% |

| Retorn Period | Water Level | Days of Interruption |

|---|---|---|

| 10 | Small | 4 |

| 25 | Medium | 7 |

| 50 | Large | 10 |

| 100 | Extreme | 20 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Santana, L.D.N.; de Oliveira, A.M.; de Oliveira, L.N.A.; Garcia, F.R. Assessing Economic Vulnerability from Urban Flooding: A Case Study of Catu, a Commerce-Based City in Brazil. Water 2026, 18, 282. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020282

Santana LDN, de Oliveira AM, de Oliveira LNA, Garcia FR. Assessing Economic Vulnerability from Urban Flooding: A Case Study of Catu, a Commerce-Based City in Brazil. Water. 2026; 18(2):282. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020282

Chicago/Turabian StyleSantana, Lais Das Neves, Alarcon Matos de Oliveira, Lusanira Nogueira Aragão de Oliveira, and Fabricio Ribeiro Garcia. 2026. "Assessing Economic Vulnerability from Urban Flooding: A Case Study of Catu, a Commerce-Based City in Brazil" Water 18, no. 2: 282. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020282

APA StyleSantana, L. D. N., de Oliveira, A. M., de Oliveira, L. N. A., & Garcia, F. R. (2026). Assessing Economic Vulnerability from Urban Flooding: A Case Study of Catu, a Commerce-Based City in Brazil. Water, 18(2), 282. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020282