Divergent Pathways and Converging Trends: A Century of Beach Nourishment in the United States Versus Three Decades in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source

2.2. Methods

3. Results

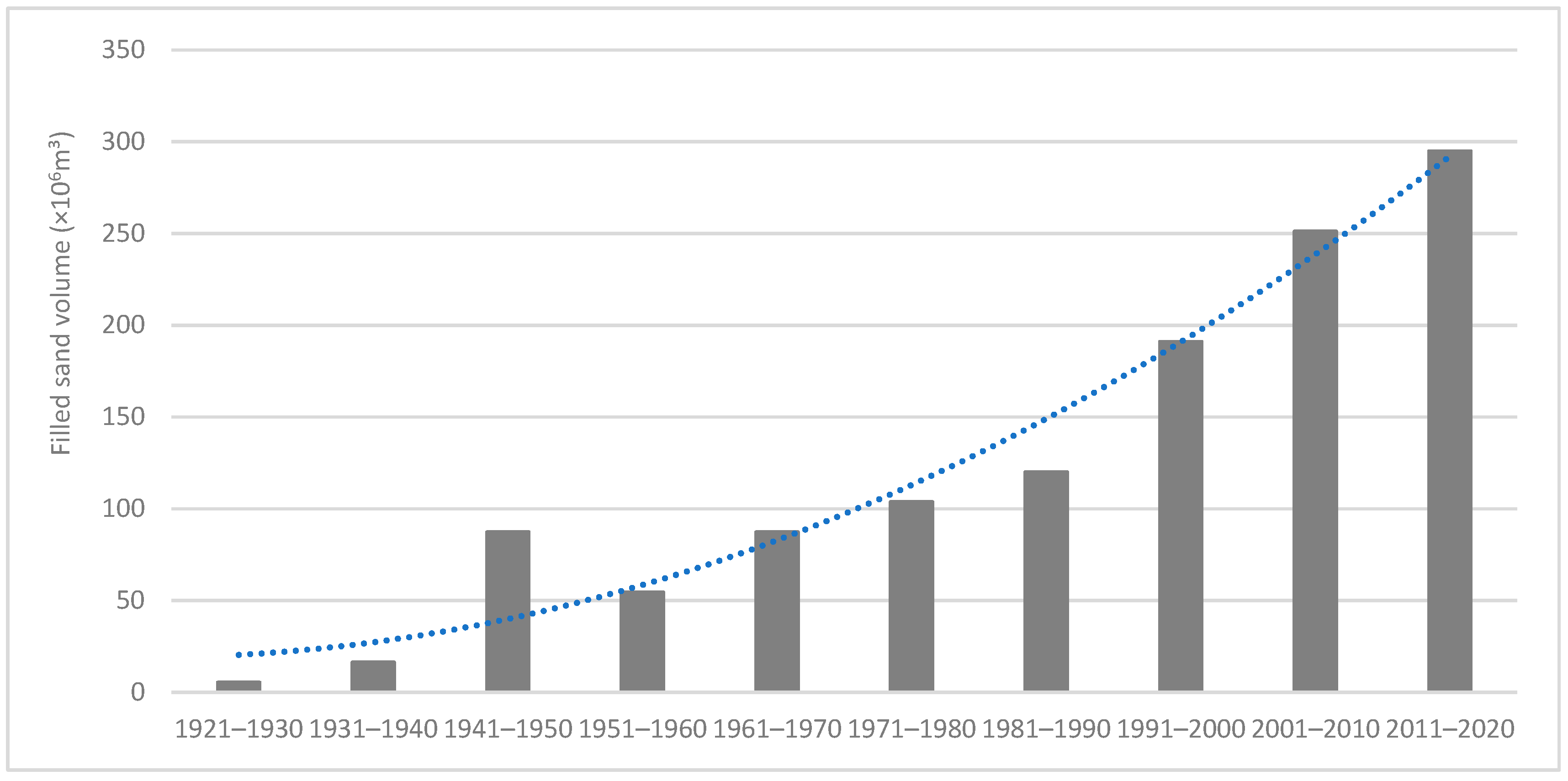

3.1. Historical Development

3.1.1. The Development of Beach Nourishment in the U.S.

3.1.2. The Development of Beach Nourishment in China

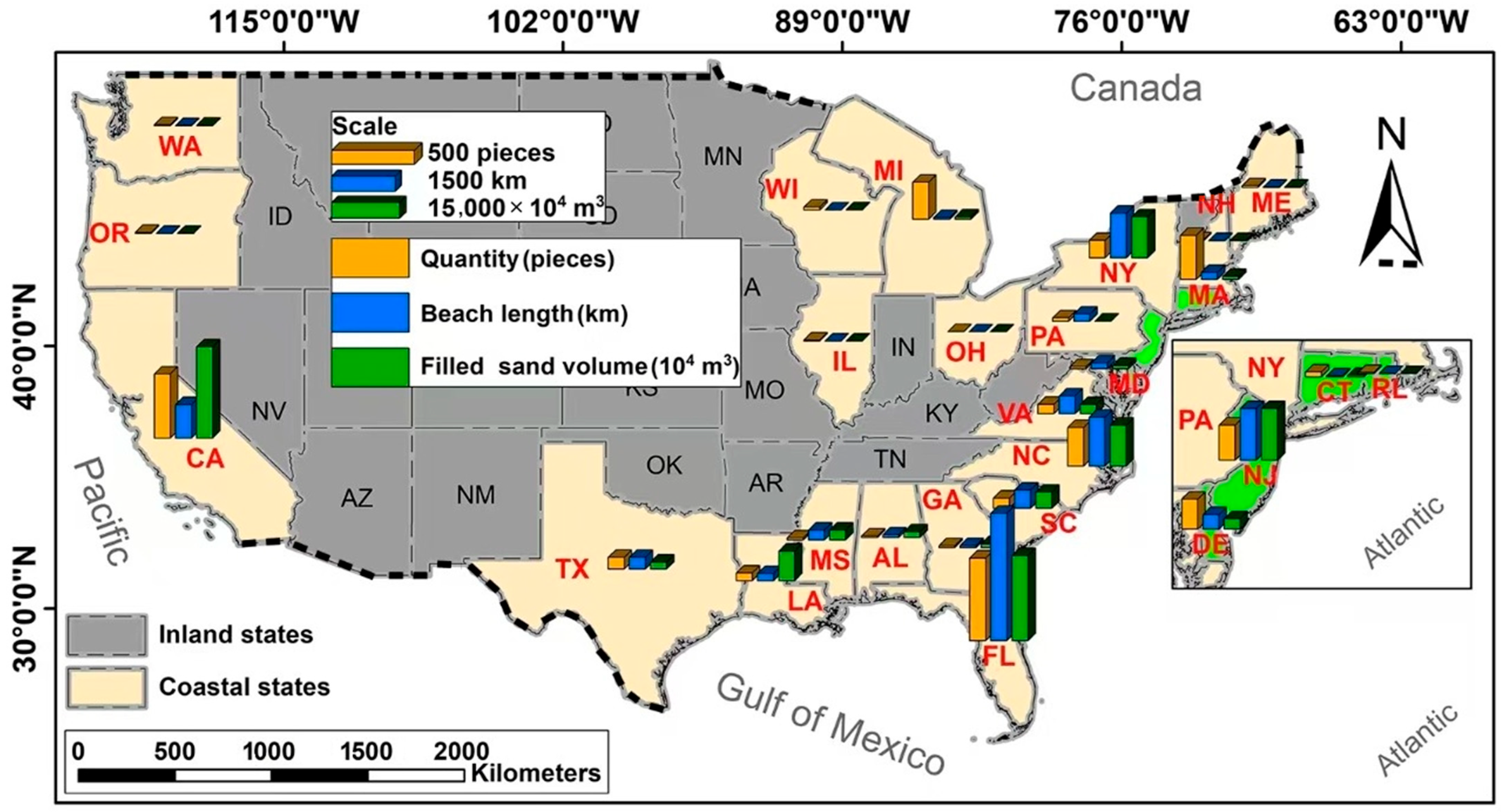

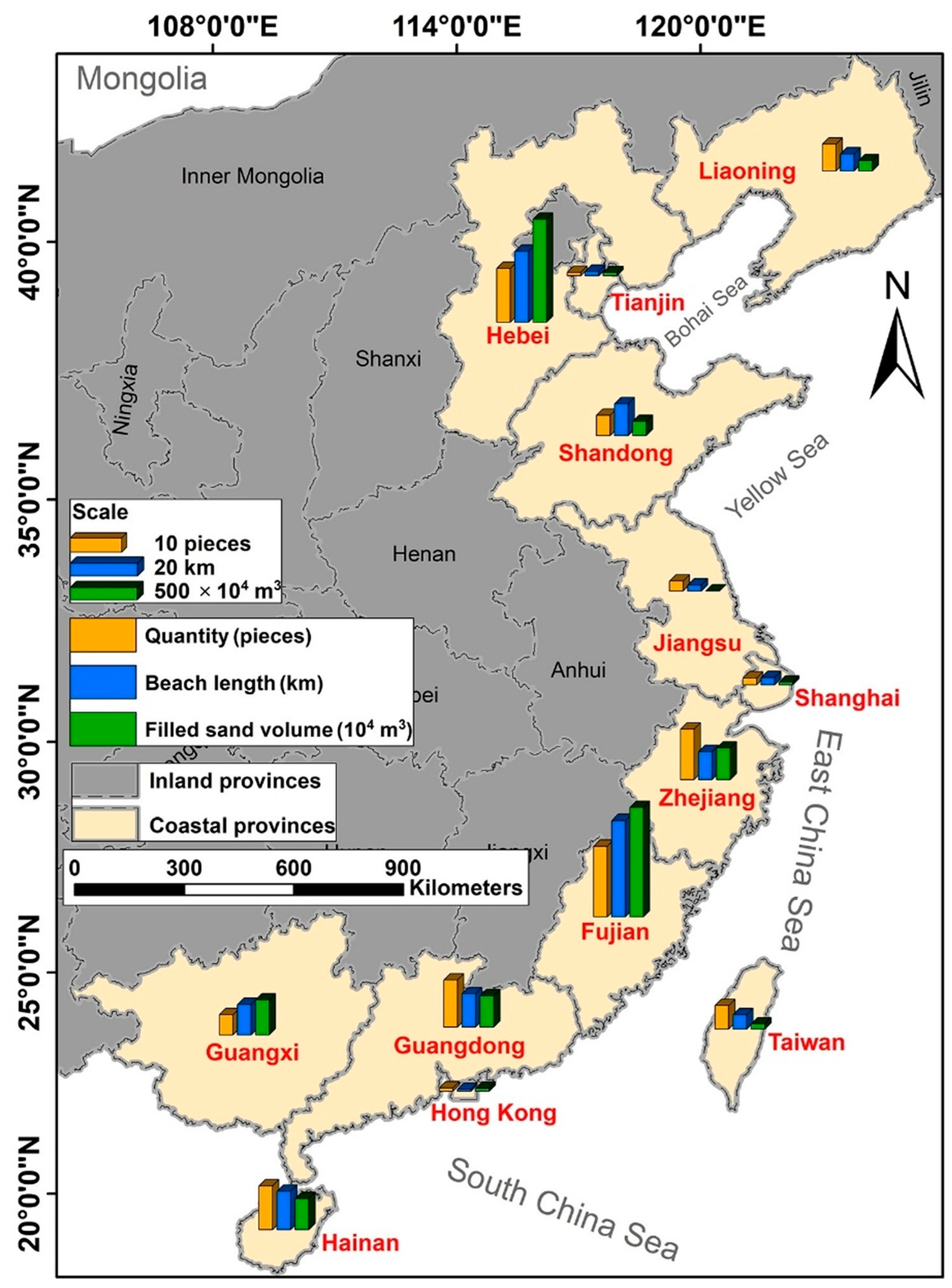

3.2. Spatial Imbalance

3.3. Converging Trends

3.4. Comparisons Between China and U.S. Regarding Beach Nourishment

3.4.1. Beach Nourishment Philosophy

3.4.2. Funding Mechanism

3.4.3. Disparities in Regulatory and Permitting Processes

3.4.4. Techniques for Predicting and Evaluating the Evolution of the Coastline

4. Discussion

4.1. Drivers of Disparities

4.1.1. Constraints of Physical Geography and Coastal Geomorphology

4.1.2. Shaping by Policy Regulations and Governance Systems

4.1.3. Drivers of Economic Dynamics and Investment Mechanisms

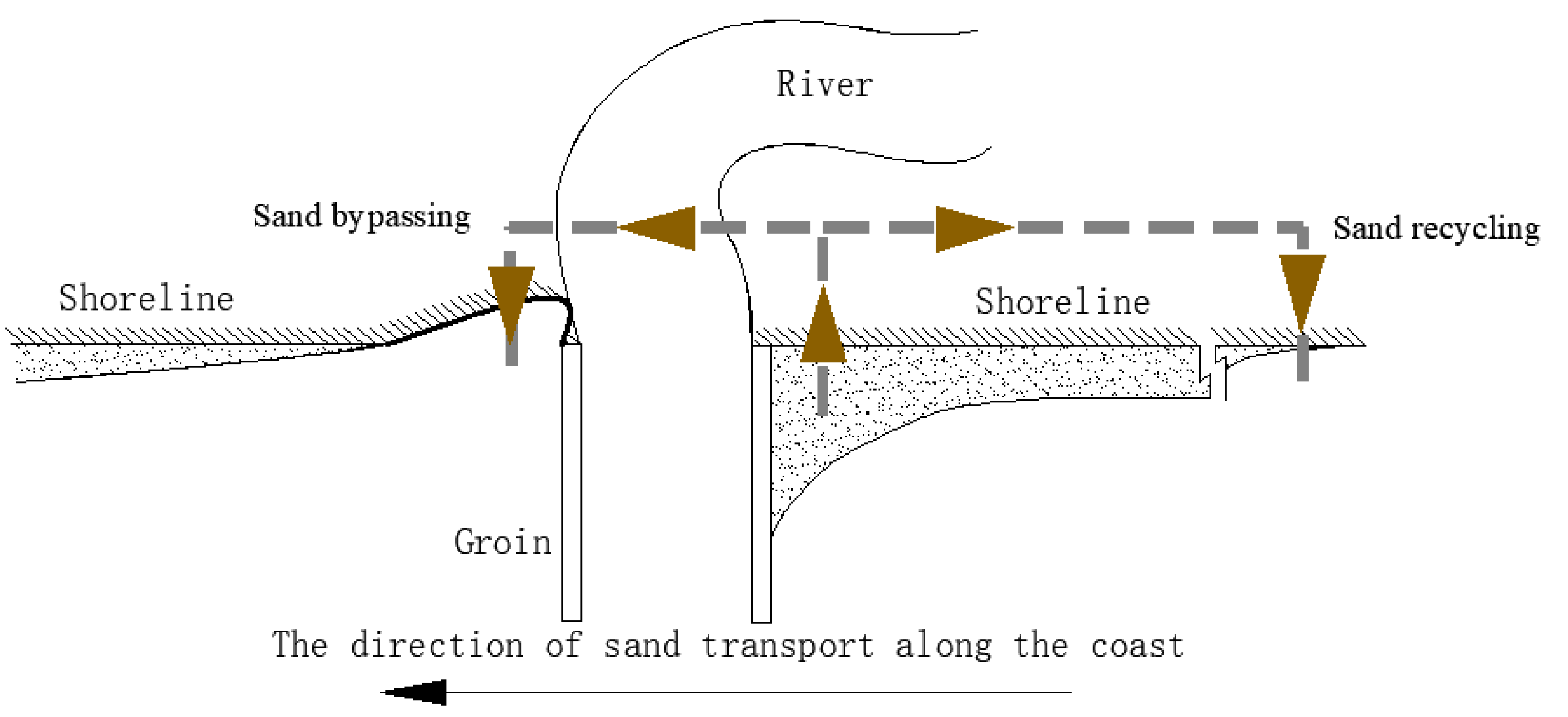

4.2. Strategic Recommendations for China

4.2.1. National Nourishment Database

4.2.2. Regional Sediment Management (RSM) Implementation

4.2.3. Ecological Engineering Integration

4.3. Future Outlook, Challenges, and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yang, Y.X.; Zhang, J.B.; Liu, S.T. What we have learnt from the beach nourishment project in Qinhuangdao. Mar. Geol. Front. 2014, 30, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astuti, Y.; Widayati, C. The Natural Resources Governance as a Moderation for the Effect of Natural Environment on Community Based Empowerment (Case study in Ringgung Beach Bandar Lampung). J. Econ. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 10, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariffin, E.H.; Zulfakar, M.S.Z.; Redzuan, N.S.; Mathew, M.J.; Akhir, M.F.; Baharim, N.B.; Baharim, N.B.; Awang, N.A.; Mokhtar, N.A. Evaluating the effects of beach nourishment on littoral morphodynamics at Kuala Nerus, Terengganu (Malaysia). J. Sustain. Sci. Manag. 2020, 15, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaacob, R.; Shaari, H.; Sapon, N.; Ahmad, M.F.; Arifin, E.H.; Zakariya, R.; Hussain, M.L. Annual changes of beach profile and nearshore sediment distribution off Dungun-Kemaman, Terengganu, Malaysia. J. Teknol. 2018, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.C.; Zhuang, Z.Y.; Cao, L.H.; Zhou, J. Influence of an artificial headland on bathing beach: A case from the Moon Bay Beach, Longkou. Mar. Geol. Front. 2014, 30, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherdvong, S. Willingness to restore jetty-created erosion at a famous tourism beach. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2019, 178, 104817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.Q.; Zhuang, Z.Y.; Feng, X.L.; Zhang, Y.H. An effective artificial beach on muddy coast: The case of Jinshan City Beach of Shanghai. Mar. Geol. Front. 2020, 36, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, R. Just 15.5% of Global Coastline Remains Intact. Eos. 21 March 2022. Available online: https://eos.org/articles/just-15-5-of-global-coastline-remains-intact (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- Defeo, O.; McLachlan, A.; Schoeman, D.S.; Schlacher, T.A.; Dugan, J.; Jones, A.; Lastra, M.; Scapini, F. Threats to sandy beach ecosystems: A review. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2009, 81, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speybroeck, J.; Bonte, D.; Courtens, W.; Gheskiere, T.; Grootaert, P.; Maelfait, J.P.; Mathys, M.; Provoost, S.; Sabbe, K.; Stienen, E.W.; et al. Beach nourishment: An ecologically sound coastal defence alternative? A review. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2006, 16, 419–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, W.Y.; Ji, G.H.; Xie, L.; Wang, D.R. Artificial sand beaches design in Sanmei Bay and Luhuitou Bay, Sanya. Mar. Geol. Front. 2014, 30, 34–37. [Google Scholar]

- Pranzini, E. Shore protection in Italy: From hard to soft engineering … and back. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2017, 156, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, H.; Brampton, A.; Capobianco, M.; Dette, H.H.; Lamm, L.; Laustrup, C.; Lechuga, A.; Spanhoff, R. Beach nourishment projects, practices, and objectives—A European overview. Coast. Eng. 2002, 47, 81–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, C.A.; Silveira, T.M.; Teixeira, S.B. Beach nourishment practice in mainland Portugal (1950–2017): Overview and retrospective. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2020, 192, 105211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, C.H.; Bishop, M.J.; Johnson, G.A.; D’Anna, L.M.; Manning, L.M. Exploiting beach filling as an unaffordable experiment: Benthic intertidal impacts propagating upwards to shorebirds. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2006, 338, 205–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, E.; Ramaekers, G.; Lodder, Q. Dutch experience with sand nourishments for dynamic coastline conservation—An operational overview. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2022, 217, 106008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, C.B.; Jones, R.A.; Goodwin, D.I.; Bishop, M.J. Nourishment practices on Australian sandy beaches: A review. J. Environ. Manag. 2012, 113, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkinson, W.R.; Ogurcak, E.D. Beach nourishment is not a sustainable strategy to mitigate climate change. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2018, 212, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherdvong, S.; Enzo, P.; Helmy, E.A.; Shin, L.Y. Jeopardizing the environment with beach nourishment. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 868, 161485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, L.; Dixon, K.; Pilkey, O.H. A Comparison of Beach Replenishment on the U.S. Atlantic, Pacific, and Gulf Coasts. J. Coast. Res. 1990, 6, 127–140. [Google Scholar]

- Castelle, B.; Turner, I.L.; Bertin, X.; Tomlinson, R. Beach nourishments at Coolangatta Bay over the period 1987–2005: Impacts and lessons. Coast. Eng. 2009, 56, 940–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stive, J.M.; Schipper, D.A.M.; Luijendijk, P.A.; Aarninkhof, S.G.J.; Gelder-Maas, C.; Vries, J.S.M.T.; de Vries, S.; Henriquez, M.; Marx, S.; Ranasinghe, R. A New Alternative to Saving Our Beaches from Sea-Level Rise: The Sand Engine. J. Coast. Res. 2020, 29, 1001–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthieu, S.D.; Bonnie, L.; Britt, R.; Arjen, L.; Thomas, S. Beach nourishment has complex implications for the future of sandy shores. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2020, 2, 70–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, F.; Dean, R.G.; Liu, J. Beach nourishment in China: Status and prospects. Coast. Eng. Proc. 2011, 1, management.31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, F.Y.; Cai, F.; Kirby, J.T.; Zheng, J.X. Morphological modeling of a nourished bayside beach with a low tide terrace. Coast. Eng. 2013, 78, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Cai, F.; Qi, H.S.; Liu, J.; Lei, G.; Zhu, J.; Cao, H.; Zheng, J.; Zhao, S.; Yu, F. A summary of beach nourishment in China: The past decade of practices. Shore Beach 2020, 88, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Wang, Q.; Zhan, C.; Sun, F.J.; Hua, W.H.; Liu, J.H.; Qi, H.; Yang, Y. Different responses of two adjacent artificial beaches to Typhoon Hato in Zhuhai, China. J. Oceanol. Limnol. 2024, 42, 511–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Cai, F.; Qi, H.S.; Lei, G.; Liu, J.H.; Zheng, J.H.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, C.; Cao, H. Low-Energy Coastal Beach Restoration Method. U.S. Patent 11,519,147 B2, 6 December 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Somphong, C.; Udo, K.; Ritphring, S.; Shirakawa, H. Beach Nourishment as an Adaptation to Future Sandy Beach Loss Owing to Sea-Level Rise in Thailand. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staudt, F.; Gijsman, R.; Ganal, C.; Mielck, F.; Wolbring, J.; Hass, H.; Goseberg, N.; Schüttrumpf, H.; Schlurmann, T.; Schimmels, S. The sustainability of beach nourishments: A review of nourishment and environmental monitoring practice. J. Coast. Conserv. 2021, 25, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elko, N.; Briggs, T.R.; Benedet, L.; Robertson, Q.; Gordon, T.; Webb, B.M.; Garvey, K. A century of U.S. beach nourishment. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2021, 199, 105406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APTIM. ASBPA National Beach Nourishment Database. 2020. Available online: https://asbpa.org/national-beach-nourishment-database/ (accessed on 1 May 2020).

- WCU. Program for the Study of Developed Shorelines. Western Carolina University, 2020. Available online: http://beachnourishment.wcu.edu/ (accessed on 27 May 2020).

- Cai, F.; Liu, G. Beach nourishment development and technological innovations in China: An overview. J. Appl. Oceanogr. 2019, 38, 452–463. [Google Scholar]

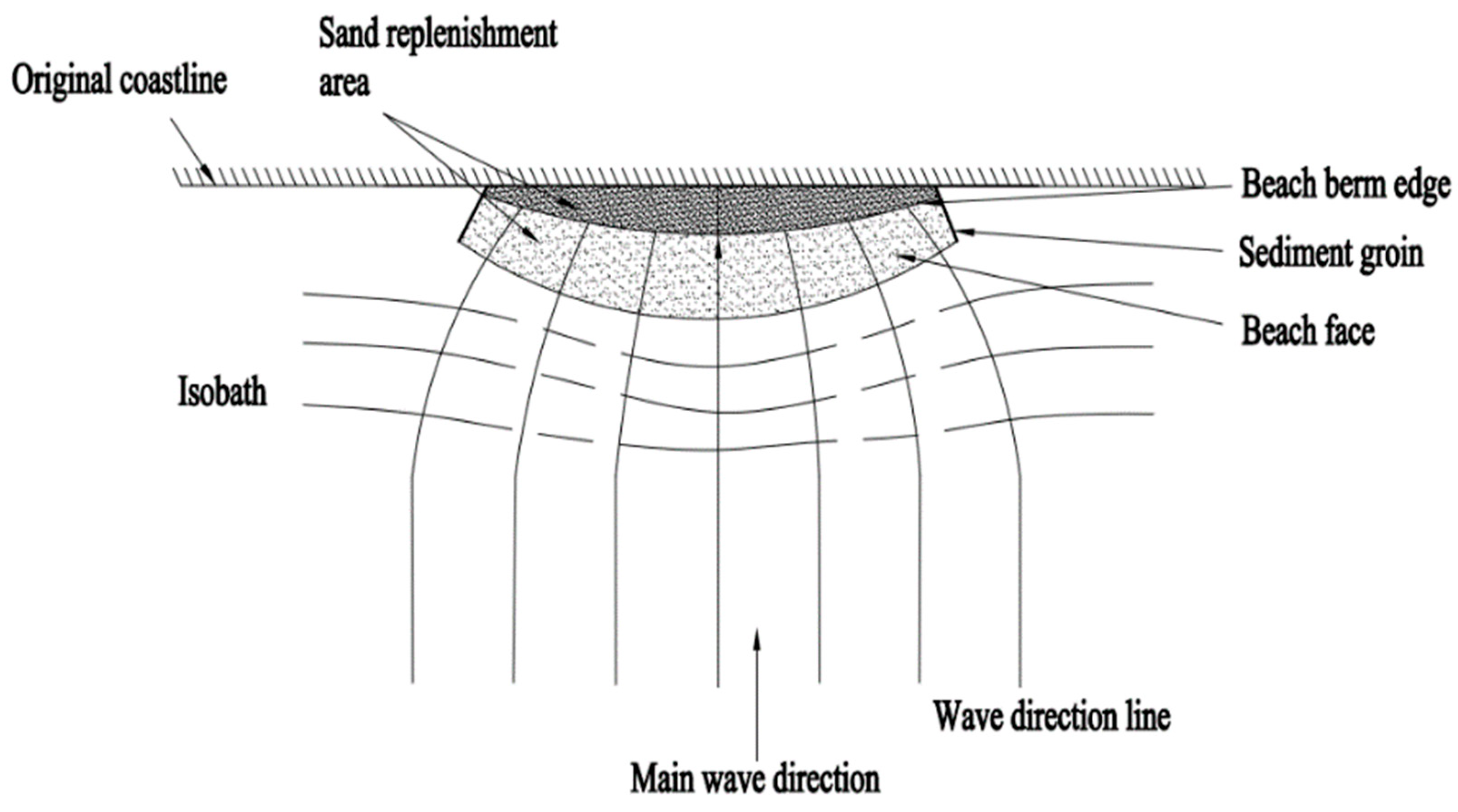

- Zhu, J.; Cai, F.; Liu, J.; Liu, G.; Qi, H.; Lei, G.; Zheng, J.; Cao, H. Application of groin system in beach nourishment. Ocean Eng. 2021, 39, 152–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Z.M.; Kang, J.J. Evaluation Theory of Urban Primacy: Theoretical Framework and Empirical Analysis. Urban Stud. 2010, 17, 33–38. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshmana, R.S.M. Measuring Urbanisation, Growth of Urban Agglomeration, Urban Growth Sustainability and Role of Urban Primacy in India. J. Asian Afr. Stud. 2024, 59, 377–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herron, W.J. Artificial beaches in Southern California. Shore Beach 1980, 48, 3–12. Available online: https://pascal-francis.inist.fr/vibad/index.php?action=getRecordDetail&idt=PASCALBTP8080286386 (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- Dean, R.G. Beach Nourishment: Theory and Practice; World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd.: Singapore, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Shore Protection Manual; Department of the Army, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers: Washington, DC, USA, 1975.

- Cao, H.M.; Cai, F.; Chen, F. Discussion on the conservation of Xiamen coastal beach and the development of marine tourism. Ocean Dev. Manag. 2009, 26, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, F. Chinese Beach Nourishment Manual; Ocean Press: Beijing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Howd, P. Beach processes and sedimentation, second edition. Eos Trans. Am. Geophys. Union 1998, 79, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Cai, F.; Chen, S.; Zhu, J.; Qi, H.S.; Cao, H.T.; Zhao, S. Beach management strategy for small islands: Case studies of China. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2019, 184, 104908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gad, S.E.; Gad, S.C. National Environmental Policy Act, USA. Encycl. Toxicol. (Second Ed.) 2005, 65, 897–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berke, P.; Roeseler, W.G. State Response to the Coastal Zone Management Act of 1972. In Coastal Zone ’83; ASCE: Reston, VA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Froede, R.C. Significant beach nourishment project underway at Dauphin Island, Alabama (USA). J. Coast. Res. 2007, 2007, 807–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dally, R.W.; Osiecki, A.D. Evaluating the Impact of Beach Nourishment on Surfing: Surf City, Long Beach Island, New Jersey, USA. J. Coast. Res. 2018, 34, 793–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houston, J.R. The economic value of beaches—A 2013 update. Shore Beach 2013, 81, 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, T.J.; Benedet, L. Beach nourishment magnitudes and trends in the U.S. J. Coast. Res. 2006, 39, 57–64. [Google Scholar]

- Kana, T.W.; Mohan, R.K. Analysis of Nourished Profile Stability following the Fifth Hunting Island (SC) Beach Nourishment Project. Coast. Eng. 1998, 33, 117–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browder, A.E.; Dean, R.G. Monitoring and comparison to predictive models of the Perdido Key beach nourishment project, Florida, USA. Coast. Eng. 2000, 39, 173–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, R.F.; Zhuang, Z.Y.; Zhao, Y.P.; Liu, J.M. Beidaihe beach nourishment: A case study of beach nourishment project in Beidaihe. Mar. Geol. Front. 2014, 30, 26–33. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G.; Cai, F.; Qi, H.S.; Zhu, J.; Lei, G.; Cao, H.M.; Zheng, J. A method to nourished beach stability assessment: The case of China. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2019, 177, 166–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontee, N. Nature-based solutions: Lessons from around the world. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng.—Marit. Eng. 2016, 169, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slobbe, E.V.; Vriend, H.; Aarninkhof, S.; Lulofs, K.; Vries, M.; Dircke, P. Building with Nature: In search of resilient storm surge protection strategies. Nat. Hazards 2013, 66, 1461–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsje, B.W.; Wesenbeeck, B.; Dekker, F.; Paalvast, P.; Bouma, T.J.; Katwijk, M.M.; de Vries, M.B. How ecological engineering can serve in coastal protection. Ecol. Eng. 2011, 37, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, M.G.; Underwood, A.J. Evaluation of ecological engineering of ‘armoured’ shorelines to improve their value as habitat. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2011, 400, 302–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quadrado, G.P.; Dillenbug, S.R.; Goulart, E.S.; Barboza, E.G. Historical and geological assessment of shoreline changes at an urbanized embayed sandy system in Garopaba, Southern Brazil. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2021, 42, 101622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saengsupavanich, C.; Yun, L.S.; Lee, L.H.; Sanitwong-Na-Ayutthaya, S. Intertidal intercepted sediment at jetties along the Gulf of Thailand. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 970592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, E.V.; Conley, D.C.; Masselink, G.; Leonardi, N.; MxCarroll, R.J.; Scott, T.; Valiente, N.G. Wave, Tide and Topographical Controls on Headland Sand Bypassing. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean 2021, 126, e2020JC017053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, K.; Jack, A.P.; Jeffrey, G.; Nathaniel, G.P. Beach response to a fixed sand bypassing system. Coast. Eng. 2013, 73, 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palaparthi, J.; Briggs, R.T. Regional Sediment Management in US Coastal States: Historical Trends and Future Predictions. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.Y.; Zhu, J.; Qi, H.S.; Liu, G.; Lei, G.; Zhao, S.H.; Zheng, J. Beach restoration strategy influenced by artificial island: A case study on the west coast of Haikou. J. Appl. Oceanogr. 2021, 40, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.K. The practice and law system studies on coastal-ocean management of America. Mar. Geol. Lett. 2022, 18, 23–27. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Finkl, C.W.; Benedet, L.; Campbell, T.J. Beach nourishment experience in the United States: Status and trends in the 20th century. Shore Beach 2006, 74, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Yang, T.; Zhang, Z.K.; Jiang, D.L.; Ren, Z.P.; Xie, L. Development of Beach Nourishment and Beach Economy in the United States and Its Implications for China’s Coastal Tourism. Trop. Geogr. 2016, 36, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Z.Y.; Cao, L.H.; Li, B.; Gao, W. An overview of beach nourishment in China. Mar. Geol. Quat. Geol. 2011, 31, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, F.; Liu, S.S.; Qi, H.S.; Buitrago, N.R.; Liu, J.H. From beach resources to law: An examination of legal instruments for beach management in China. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2024, 253, 107–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flick, R.E. The myth and reality of southern California beaches. Shore Beach 1993, 61, 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Leatherman, S.P. Shoreline stabilization approaches in response to sea level rise: U.S. experience and implications for Pacific Island and Asian nations. Water Air Soil Pollut. 1996, 92, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, K.Z.; Wang, H.; Sun, J.W.; Zhang, J.B.; Liu, Z.B. Including Wave Diffraction in XBeach: Model Extension and Validation. J. Coast. Res. 2019, 36, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargono, S.; Augusto, E.; Wiranto, A.P.; Pramana, R. Simulation of shoreline change related coastal structure. Adv. Sci. Lett. 2018, 24, 9089–9093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, K.E.; Thomas, R.C.; Frey, A.E. Shoreline Change Modeling Using One-Line Models: Application and Comparison of GenCade, Unibest, and Litpak; ERDC/CHL CHETN-IV-102; U.S. Army Engineer Research and Development Center: Vicksburg, MS, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Roelvink, D.; McCall, R.; Mehvar, S.; Nederhoff, K.; Dastgheib, A. Improving predictions of swash dynamics in XBeach: The role of groupiness and incident-band runup. Coast. Eng. 2018, 134, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Montblanc, T.; Duo, E.; Ciavola, P. Dune reconstruction and revegetation as a potential measure to decrease coastal erosion and flooding under extreme storm conditions. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2020, 188, 105075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Cai, F.; Shi, F.Y.; Qi, H.S.; Lei, G.; Liu, J.H.; Cao, H.; Zheng, J. Beach response to breakwater layouts of drainage pipe outlets during beach nourishment. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2019, 228, 106354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Shi, F.Y.; Cai, F.; Wang, Q.; Qi, H.S.; Zhan, C.; Liu, J.; Liu, G.; Lei, G. Influences of beach berm height on beach response to storms: A numerical study. Appl. Ocean Res. 2022, 121, 103090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, F.Y.; Kirby, J.T.; Harris, J.C.; Geiman, J.D.; Grilli, S.T. A high-order adaptive time-stepping TVD solver for Boussinesq modeling of breaking waves and coastal inundation. Ocean. Model. 2012, 43–44, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huisman, B.J.; Wijsman, J.W.; Arens, S.M.; Vertegaal, C.T.M.; Valk, L.; Donk, S.C.; Vreugdenhil, H.S.I.; Taal, M.D. 10-Years Evaluation of the Sand Motor: Results of the Monitoring-and Evaluation Program (MEP) for the Period 2011 to 2021; Deltares: Delft, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, C.L.; Zhu, J.; Cai, F.; Wang, L.H.; Qi, H.S.; Liu, J.H.; Lei, G.; Zhao, S. Spatial and Temporal distribution of wave energy on low energy coasts under the effect of beach restoration project. Oceanol. Limnol. Sin. 2021, 52, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, N.L.; Nordstrom, K.F.; Eliot, I.; Masselink, G. ‘Low energy’ sandy beaches in marine and estuarine environments: A review. Geomorphology 2002, 48, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, H.S.; Cai, F.; Lei, G. A Design Method for Beach Nourishment in Strongly Eroded Bare Shore Sections. China ZL201810198175.6, 29 June 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Shu, F.F.; Cai, F.; Qi, H.S.; Liu, J.H.; Lei, G.; Zheng, J.X. Morphodynamics of an Artificial Cobble Beach in Tianquan Bay, Xiamen, China. J. Ocean Univ. China 2019, 18, 868–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, R.G.; Dalrymple, R.A. Coastal Processes with Engineering Applications; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001; pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luijendijk, A.P.; Borsje, B.W.; Aarninkhof, S.G.J. Building with nature in the coastal environment and field applications. Environ. Coast. Offshore 2013, 36–45. Available online: https://cdn.coverstand.com/9890/143864/143864.2.pdf (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- Morales, J.A. The Rocky Coastlines of the Canary Islands. In The Spanish Coastal Systems (Dynamic Processes, Sediments and Management); Chapter 8; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 167–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, L. Sand and Sustainability: Finding New Solutions for Environmental Governance of Global Sand Resources; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Country | Earliest Recorded Nourishment Year | Total Length of Coastline (km) | Statistics Cut-Off Year | Number of Nourishment Projects | Total Nourished Beach Length (km) | Total Filled Sand Volume (104 m3) | Filled Sand Volume over the Last Decade (104 m3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U.S. | 1919 | 199,924 | 2020 | 3200 | 15,993 | 120,000 | 29,507 |

| China | 1992 | 17726 | 2020 | 113 | 117 | 2600 | 2028 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Jiang, M.; Zhu, J.; Sun, F.; Mao, M.; Dong, P.; Zhan, C.; Li, G.; Zhang, X.; Dong, X.; Jiang, X.; et al. Divergent Pathways and Converging Trends: A Century of Beach Nourishment in the United States Versus Three Decades in China. Water 2026, 18, 283. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020283

Jiang M, Zhu J, Sun F, Mao M, Dong P, Zhan C, Li G, Zhang X, Dong X, Jiang X, et al. Divergent Pathways and Converging Trends: A Century of Beach Nourishment in the United States Versus Three Decades in China. Water. 2026; 18(2):283. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020283

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiang, Min, Jun Zhu, Fengjuan Sun, Miaohua Mao, Ping Dong, Chao Zhan, Guoqing Li, Xingjie Zhang, Xinlan Dong, Xing Jiang, and et al. 2026. "Divergent Pathways and Converging Trends: A Century of Beach Nourishment in the United States Versus Three Decades in China" Water 18, no. 2: 283. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020283

APA StyleJiang, M., Zhu, J., Sun, F., Mao, M., Dong, P., Zhan, C., Li, G., Zhang, X., Dong, X., Jiang, X., & Wang, X. (2026). Divergent Pathways and Converging Trends: A Century of Beach Nourishment in the United States Versus Three Decades in China. Water, 18(2), 283. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020283