Occurrence, Seasonal Variation, and Microbial Drivers of Antibiotic Resistance Genes in a Residential Secondary Water Supply System

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling Strategy and Frequency

2.2. Determination of Antibiotic Resistance Levels

2.2.1. Detection of Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria

2.2.2. Quantification of Antibiotic Resistance Genes

2.3. Microbial Community Analysis

2.4. Biological Water Quality Indicators

2.4.1. Determination of Assimilable Organic Carbon

2.4.2. Measurement of Bacterial Regrowth Potential

2.4.3. Heterotrophic Plate Count

2.4.4. Flow Cytometry Analysis

2.5. Physicochemical Water Quality Parameters

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Occurrence of Antibiotic Resistance

3.1.1. Abundance of Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria

3.1.2. Abundance of Antibiotic Resistance Genes

3.2. Drivers of Antibiotic Resistance and Environmental Factors

3.3. Microbial Community Composition and Its Association with Antibiotic Resistance

3.3.1. Bacterial Community Composition and Analysis

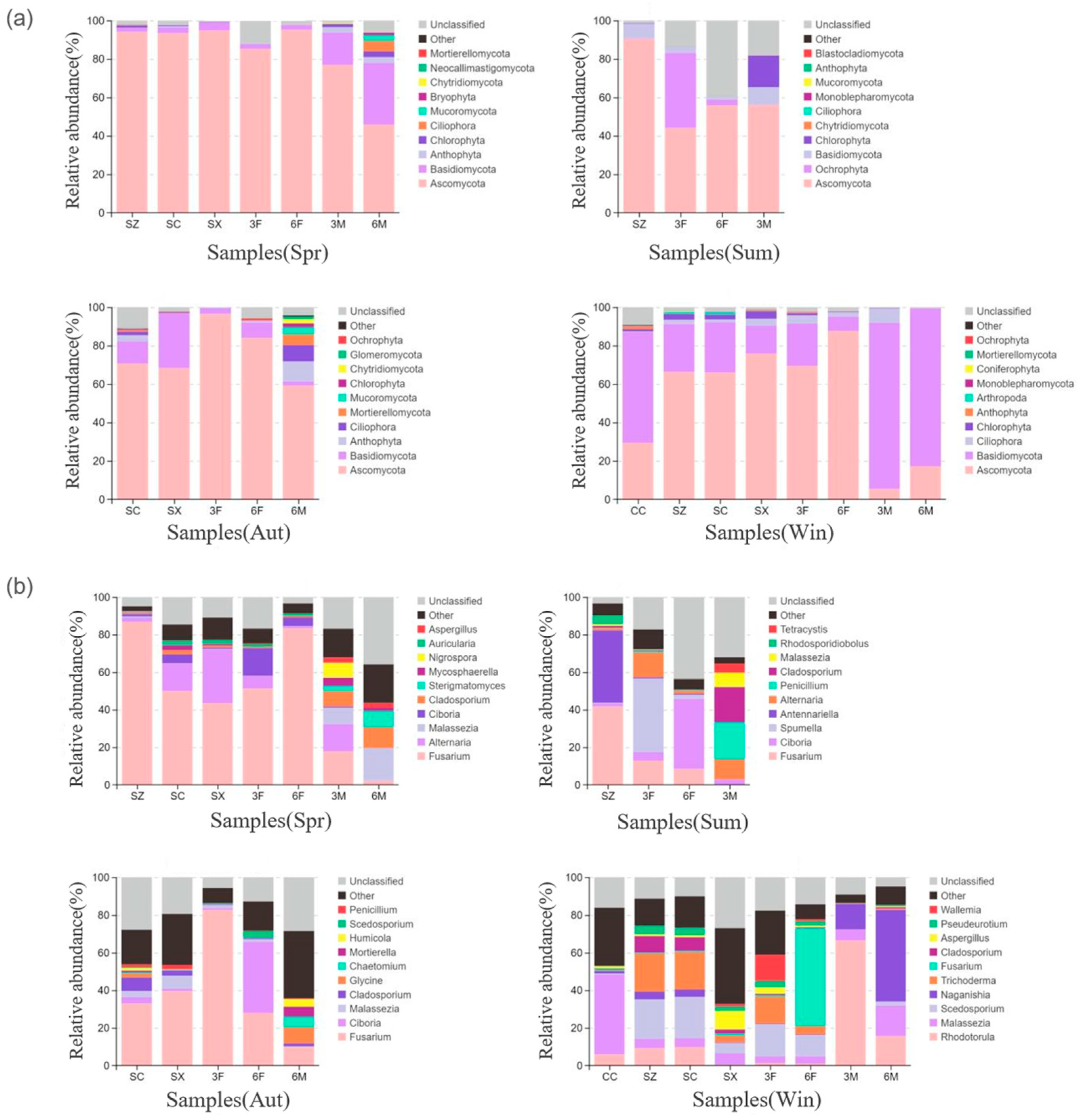

3.3.2. Fungal Community Composition and Analysis

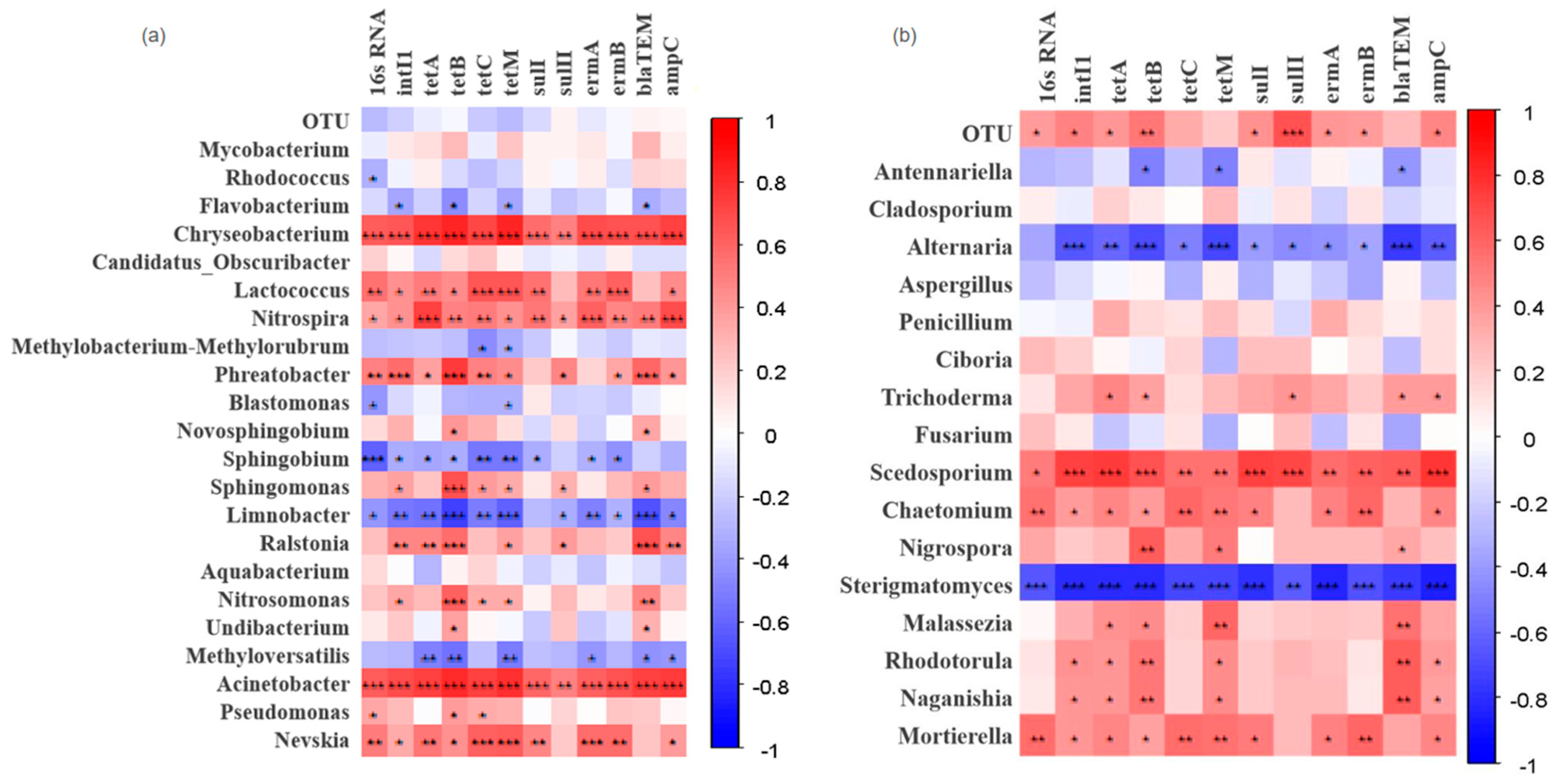

3.3.3. Correlation Between Microbial Communities and Antibiotic Resistance

4. Conclusions and Outlook

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ben, Y.J.; Fu, C.X.; Hu, M.; Liu, L.; Wong, M.H.; Zheng, C.M. Human health risk assessment of antibiotic resistance associated with antibiotic residues in the environment: A review. Environ. Res. 2019, 169, 483–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flach, K.A.; Bones, U.A.; Wolff, D.B.; De Oliveira Silveira, A.; Da Rosa, G.M.; Carissimi, E.; Silvestri, S. Antibiotic resistant bacteria and genes (ARB and ARG) in water and sewage treatment units: A review. Environ. Nanotechnol. Monit. Manag. 2024, 21, 100941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.Y.; Ma, W.C.; Zhong, D. The stress response mechanisms and resistance change of chlorine-resistant microbial community at multi-phase interface under residual antibiotics in drinking water distribution system. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 438, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, X.; Liu, C.; Liu, M.; Han, X.; Zhu, L.; Bai, X. The role of pipe biofilms on dissemination of viral pathogens and virulence factor genes in a full-scale drinking water supply system. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 432, 128694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, Q.H.; Sun, M.; Lin, T.; Zhang, Y.X.; Wei, X.H.; Wu, S.; Zhang, S.H.; Pang, R.; Wang, J.; Ding, Y.; et al. Characteristics of Antibiotic Resistance Genes and Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria in Full-Scale Drinking Water Treatment System Using Metagenomics and Culturing. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 798442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, C.W.; Zhang, Y.L.; Marrs, C.F.; Ye, W.; Simon, C.; Foxman, B.; Nriagu, J. Prevalence of Antibiotic Resistance in Drinking Water Treatment and Distribution Systems. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 5714–5718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.P.; Li, W.Y.; Zhang, J.P.; Qi, W.Q.; Li, Y.; Chen, S.; Zhou, W. Prevalence of antibiotic resistance genes in drinking water and biofilms: The correlation with the microbial community and opportunistic pathogens. Chemosphere 2020, 259, 127483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Ondon, B.S.; Ho, S.-H.; Zhou, Q.; Li, F. Drinking water sources as hotspots of antibiotic-resistant bacteria (ARB) and antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs): Occurrence, spread, and mitigation strategies. J. Water Process Eng. 2023, 53, 103907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholipour, S.; Shamsizadeh, Z.; Gwenzi, W.; Nikaeen, M. The bacterial biofilm resistome in drinking water distribution systems: A systematic review. Chemosphere 2023, 329, 138642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aggarwal, S.; Gomez-Smith, C.K.; Jeon, Y.; LaPara, T.M.; Waak, M.B.; Hozalski, R.M. Effects of Chloramine and Coupon Material on Biofilm Abundance and Community Composition in Bench-Scale Simulated Water Distribution Systems and Comparison with Full-Scale Water Mains. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 13077–13088. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, F.L.; Zhu, J.N.; Li, J.Z.; Fu, C.Y.; He, G.L.; Lin, Q.F.; Li, C.; Song, S. The occurrence, formation and transformation of disinfection byproducts in the water distribution system: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 867, 161497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.C.; Hu, Y.X.; Zhou, S.; Meng, D.; Xia, S.Q.; Wang, H. Unraveling bacterial and eukaryotic communities in secondary water supply systems: Dynamics, assembly, and health implications. Water Res. 2023, 245, 120597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fish, K.E.; Osborn, A.M.; Boxall, J. Characterising and understanding the impact of microbial biofilms and the extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix in drinking water distribution systems. Environ. Sci.-Water Res. Technol. 2016, 2, 614–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.; Pullerits, K.; Keucken, A.; Perssonz, K.M.; Paul, C.J.; Rådström, P. Bacterial release from pipe biofilm in a full-scale drinking water distribution system. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2019, 5, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babic, M.N.; Gunde-Cimerman, N. Water-Transmitted Fungi Are Involved in Degradation of Concrete Drinking Water Storage Tanks. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Yang, H.; Liu, H.; Zhang, X.-X.; Ma, L. Anthropogenic contributions to antibiotic resistance gene pollution in household drinking water revealed by machine-learning-based source-tracking. Water Res. 2023, 246, 120682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lerminiaux, N.A.; Cameron, A.D.S. Horizontal transfer of antibiotic resistance genes in clinical environments. Can. J. Microbiol. 2019, 65, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, D.; Zhou, Z.Y.; Ma, W.C.; Ma, J.; Feng, W.A.; Li, J.X.; Du, X. Antibiotic enhances the spread of antibiotic resistance among chlorine-resistant bacteria in drinking water distribution system. Environ. Res. 2022, 211, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiwari, A.; Gomez-Alvarez, V.; Siponen, S.; Sarekoski, A.; Hokajarvi, A.M.; Kauppinen, A.; Torvinen, E.; Miettinen, I.T.; Pitkanen, T. Bacterial Genes Encoding Resistance Against Antibiotics and Metals in Well-Maintained Drinking Water Distribution Systems in Finland. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 803094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, M.; Liu, L.; Wang, D.-N.; Yang, D.; Liu, W.-L.; Yin, J.; Yang, Z.-W.; Wang, H.-R.; Qiu, Z.-G.; Shen, Z.-Q. Chlorine disinfection promotes the exchange of antibiotic resistance genes across bacterial genera by natural transformation. ISME J. 2020, 14, 1847–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Q.Q.; Wen, G.; Cui, Y.H.; Cao, R.H.; Xu, X.Q.; Wu, G.H.; Wang, J.Y.; Huang, T.L. Occurrence and control of fungi in water: New challenges in biological risk and safety assurance. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 860, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Hou, Y.; Wei, L.; Wei, W.; Zhang, K.; Duan, H.; Ni, B.-J. Chlorination-induced spread of antibiotic resistance genes in drinking water systems. Water Res. 2025, 274, 123092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.Q. Molecular Insights into Extracellular Polymeric Substances in Activated Sludge. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 7742–7750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asmara, A.A.; Wacano, D.; Wong, Y.J.; Im, D.; Nishimura, F. Determining the contribution of stream morphometry and microbial extracellular polymeric substances in the spread patterns of antimicrobial resistance. Water Res. 2026, 288, 124583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.Y.; Hu, Y.R.; Jiang, L.; Yao, S.J.; Lin, K.F.; Zhou, Y.B.; Cui, C.Z. Removal of antibiotic resistance genes and control of horizontal transfer risk by UV, chlorination and UV/chlorination treatments of drinking water. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 358, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Sha, X.N.; Chen, X.F.; Zhuo, H.H.; Xie, W.M.; Zhou, Z.; He, X.M.; Wu, L.; Li, B.L. Removal and distribution of antibiotics and resistance genes in conventional and advanced drinking water treatment processes. J. Water Process Eng. 2022, 50, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsholo, K.; Molale-Tom, L.G.; Horn, S.; Bezuidenhout, C.C. Distribution of antibiotic resistance genes and antibiotic residues in drinking water production facilities: Links to bacterial community. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0299247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Zhou, Z.C.; Zhu, L.; Han, Y.; Lin, Z.J.; Feng, W.Q.; Liu, Y.; Shuai, X.Y.; Chen, H. Antibiotic resistance genes and microcystins in a drinking water treatment plant. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 258, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, K.; Lin, W.F.; Zhu, S.; Zhang, S.H.; Yu, X. Biofiltration and disinfection codetermine the bacterial antibiotic resistome in drinking water: A review and meta-analysis. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2020, 14, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, K.; Guo, L.Z.; Ye, C.S.; Zhu, J.W.; Zhang, M.L.; Yu, X. Accumulation of antibiotic resistance genes in full-scale drinking water biological activated carbon (BAC) filters during backwash cycles. Water Res. 2021, 190, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertelli, C.; Courtois, S.; Rosikiewicz, M.; Piriou, P.; Aeby, S.; Robert, S.; Loret, J.F.; Greub, G. Reduced Chlorine in Drinking Water Distribution Systems Impacts Bacterial Biodiversity in Biofilms. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, Y.; Yang, S.; Chiang, T.Y.; Zhu, X.; Hu, J. Controlling Biofilm Growth and Its Antibiotic Resistance in Drinking Water by Combined UV and Chlorination Processes. Water 2022, 14, 3643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.B.; Hu, H.T.; Chen, S.S.; Schwarz, C.; Yin, H.; Hu, C.S.; Li, G.W.; Shi, B.Y.; Huang, J.G. UV pretreatment reduced biofouling of ultrafiltration and controlled opportunistic pathogens in secondary water supply systems. Desalination 2023, 548, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.J.; Cai, Y.W.; Li, G.Y.; Wang, W.J.; Wong, P.K.; An, T.C. Response mechanisms of different antibiotic-resistant bacteria with different resistance action targets to the stress from photocatalytic oxidation. Water Res. 2022, 218, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.J.; Yu, G. Challenges and pitfalls in the investigation of the catalytic ozonation mechanism: A critical review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 436, 129157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cockerill, F.R.; Clinical & Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing: Twenty-Third Informational Supplement; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tian, H.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, D.; Li, W. Occurrence, Seasonal Variation, and Microbial Drivers of Antibiotic Resistance Genes in a Residential Secondary Water Supply System. Water 2026, 18, 281. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020281

Tian H, Zhou Y, Zhang D, Li W. Occurrence, Seasonal Variation, and Microbial Drivers of Antibiotic Resistance Genes in a Residential Secondary Water Supply System. Water. 2026; 18(2):281. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020281

Chicago/Turabian StyleTian, Huaiyu, Yu Zhou, Dawei Zhang, and Weiying Li. 2026. "Occurrence, Seasonal Variation, and Microbial Drivers of Antibiotic Resistance Genes in a Residential Secondary Water Supply System" Water 18, no. 2: 281. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020281

APA StyleTian, H., Zhou, Y., Zhang, D., & Li, W. (2026). Occurrence, Seasonal Variation, and Microbial Drivers of Antibiotic Resistance Genes in a Residential Secondary Water Supply System. Water, 18(2), 281. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020281