Impact of Climate and Land Cover Dynamics on River Discharge in the Klambu Dam Catchment, Indonesia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methodology

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data

2.2.1. Hydrometeorological Data Calibration and Validation

2.2.2. Land Cover and Soil Type Calibration and Validation

2.3. Methodology

2.3.1. Thornthwaite-Mather Analysis

- If P > PET, the excess water will add to soil moisture until it reaches WHC. Once the WHC is full, the surplus water is considered surface runoff.

- If P < PET, the soil will release water from its moisture reserves to meet PET. If soil moisture is insufficient, a water deficit will occur.

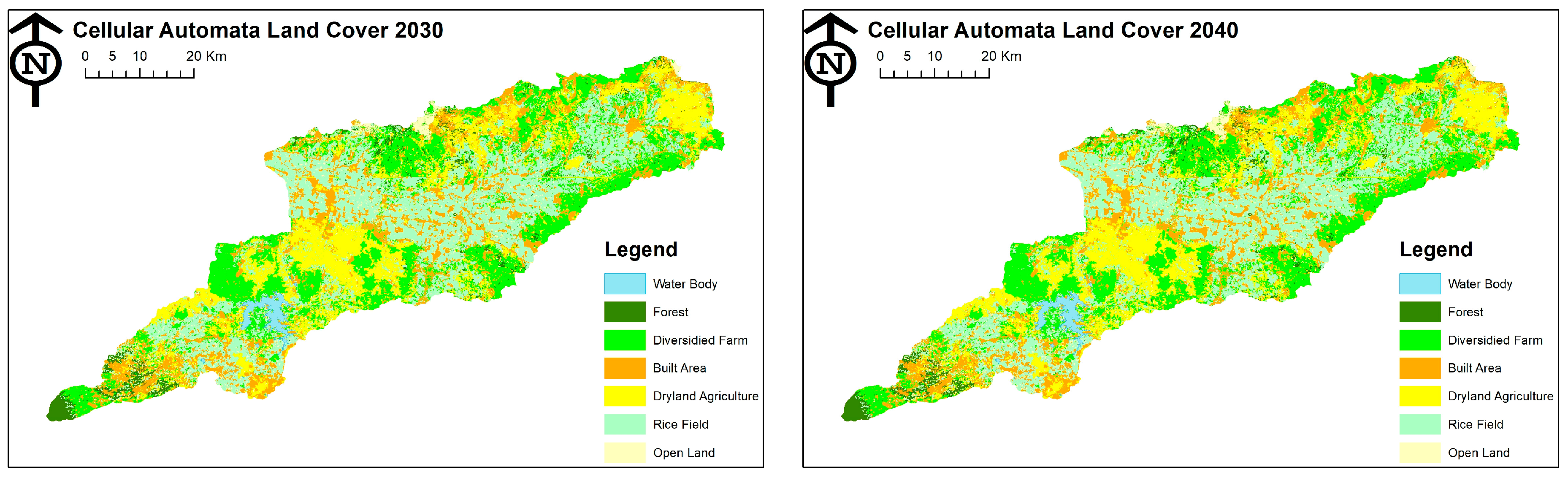

2.3.2. Land Cover Analysis and Simulation

2.3.3. Impacts of Climate and Land Use Projections on Discharge

- Land Cover Forcing: Raster layers of future land cover classes were translated into hydrological parameters—imperviousness, infiltration rates and roughness coefficients according to established lookup tables [55].

- Climate Forcing: Monthly climate projections were processed to generate design storm events and long-term precipitation series consistent with each IPCC scenario [43].

- Hydrological Simulation: The hydrological model used both sets of inputs to simulate runoff generation, channel routing and baseflow dynamics [40].

- Scenario Analysis: River discharge outputs were evaluated across multiple climate scenarios to quantify the relative influence of land cover change, climate variability, and their combined effects on hydrological conditions. To assess future climate impacts under varying emission trajectories, this study employs a set of standardized scenarios from the IPCC AR6 framework, representing a continuum from low to very high radiative forcing pathways. These include Scenario 2.6 (C3), Scenario 4.5 (C6), Scenario 7.0 (C7), and Scenario 8.5 (C8), which collectively capture a broad range of projected changes in temperature and precipitation. Although these scenarios are coded using the SSP–RCP naming convention, the present study focuses primarily on their climatic forcing outputs, rather than their socioeconomic narratives. This approach provides a robust basis for evaluating future shifts in wet and dry season intensity and their potential impacts on erosion, runoff generation, and the long-term service life of the Klambu Dam catchment.

3. Result and Discussion

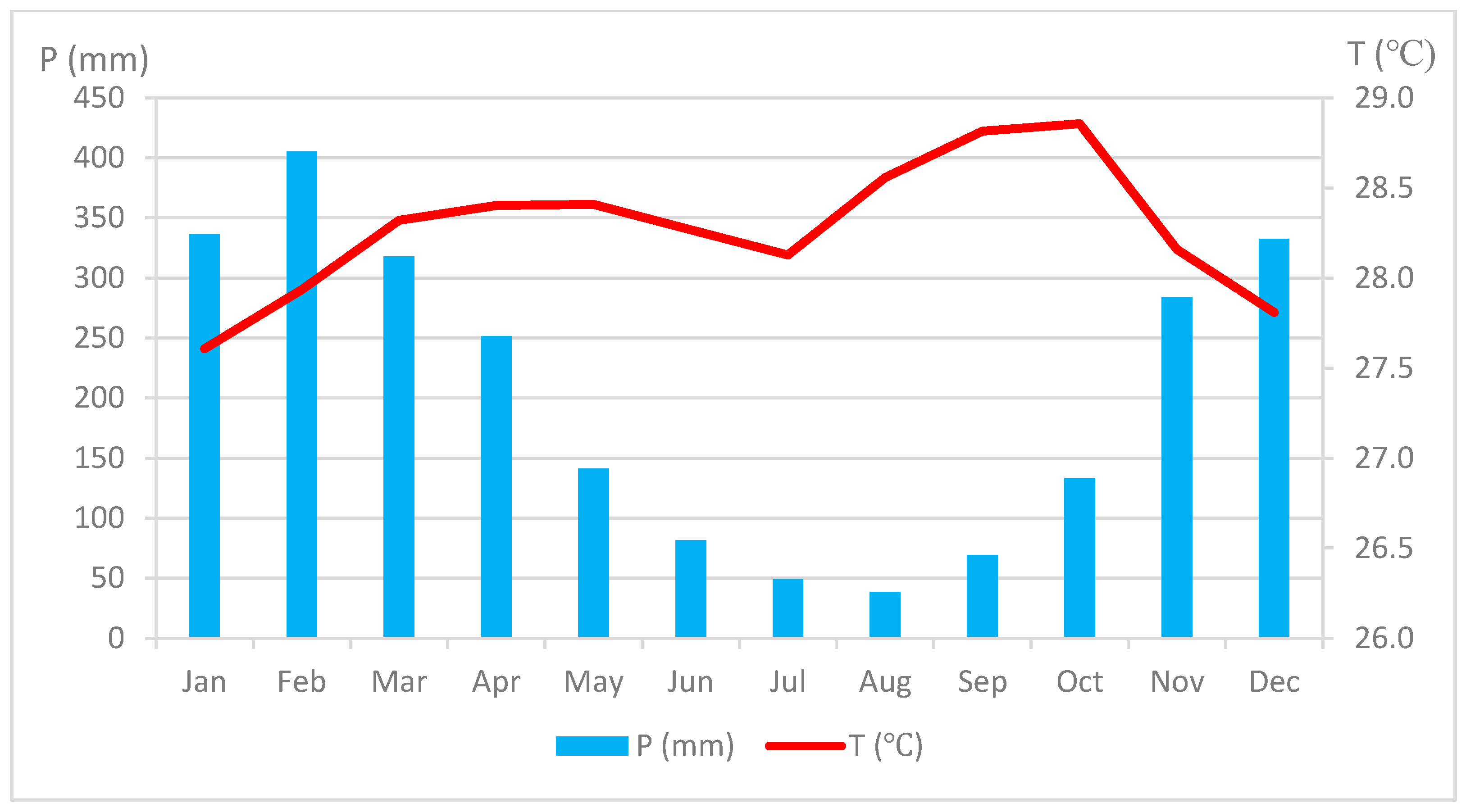

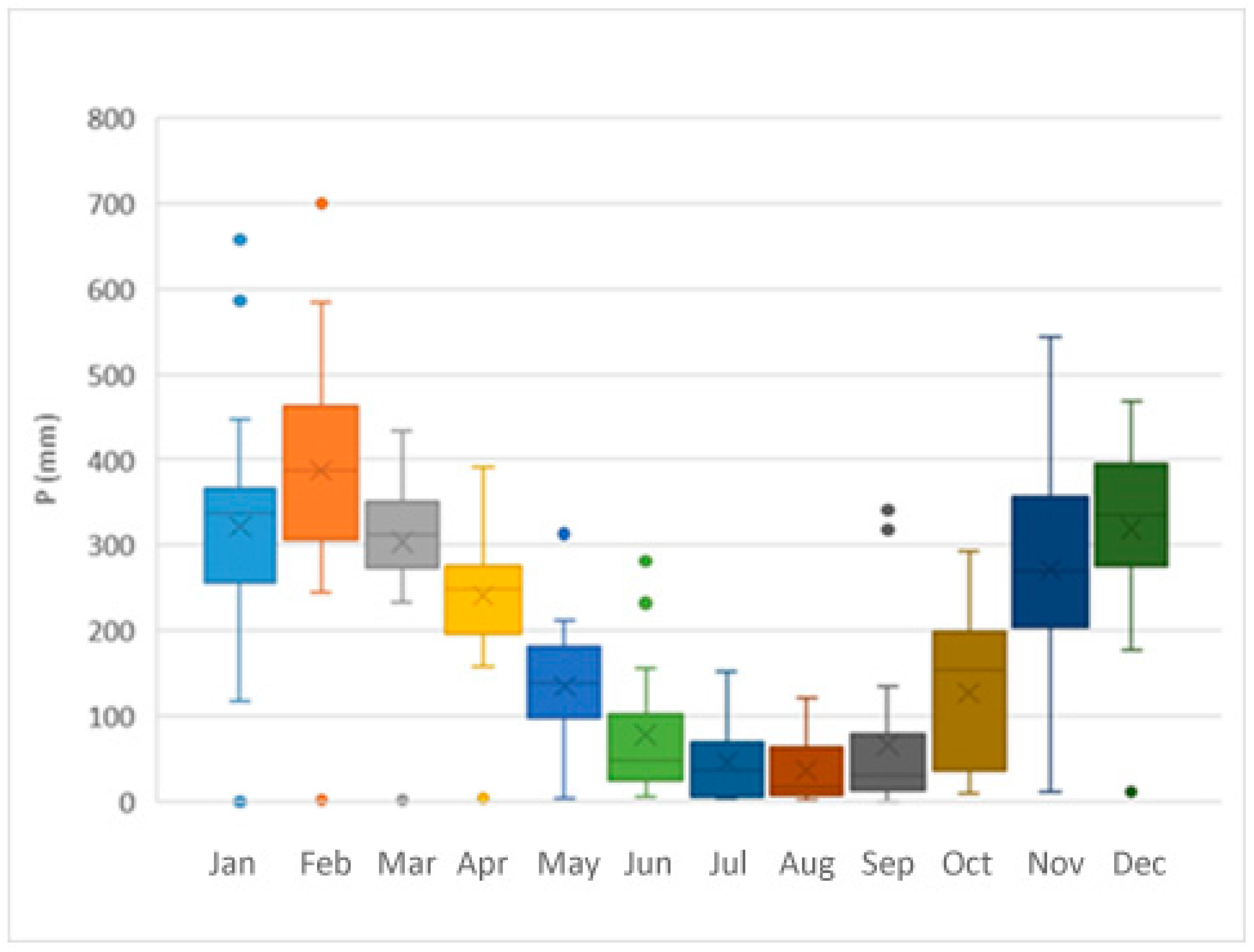

3.1. Air Temperature and Precipitation Trends

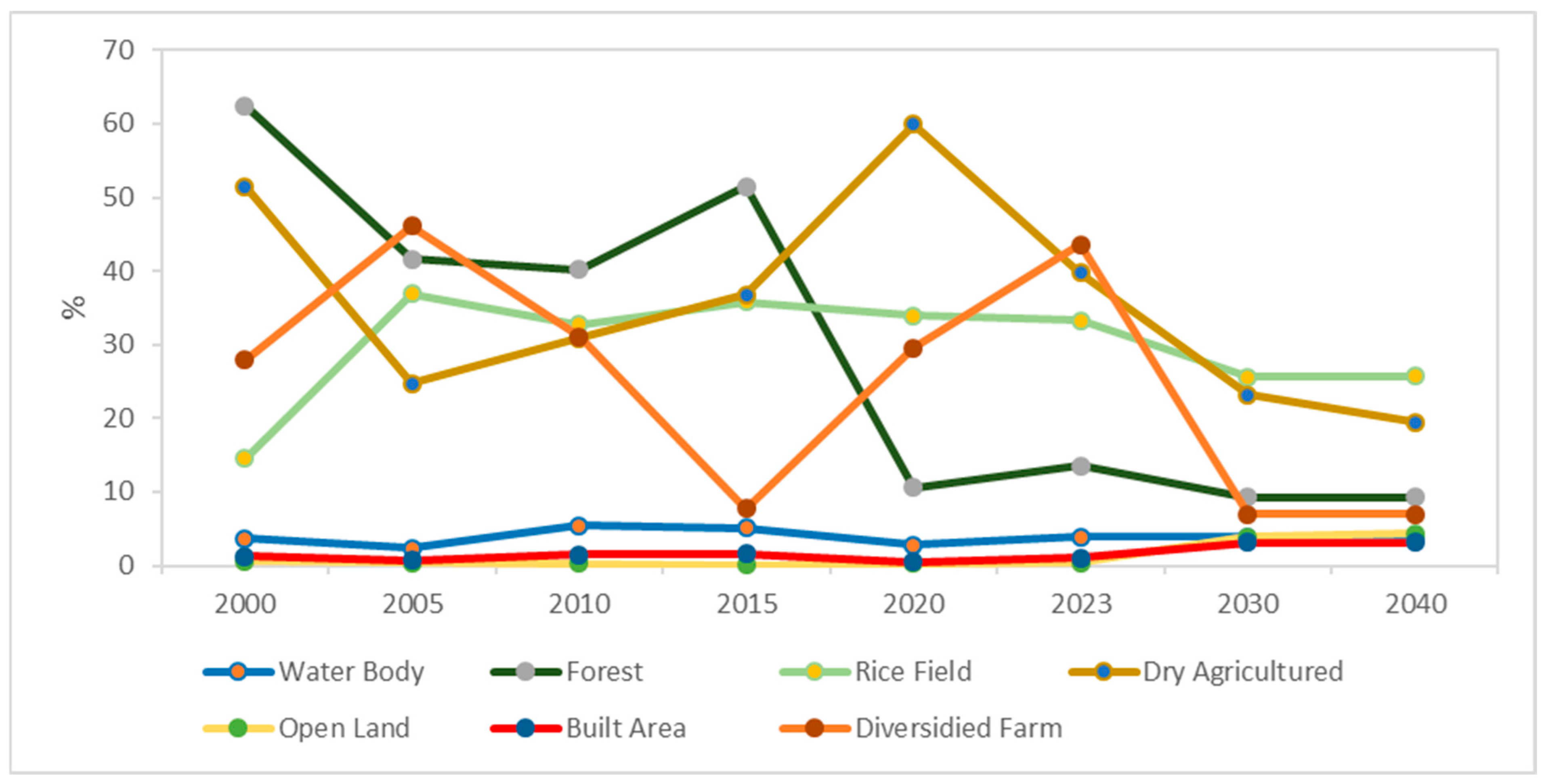

3.2. Changes in Land Cover and Use

3.3. Water Resources

3.4. Discussion

3.5. Implications for Water Resource Management and Adaptive Strategies

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kubiak-Wójcicka, K. Variability of Air Temperature, Precipitation and Outflows in the Vistula Basin (Poland). Resources 2020, 9, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Nunno, F.; Diodato, N.; Bellocchi, G.; Tricarico, C.; de Marinis, G.; Granata, F. Evapotranspiration Analysis in Central Italy: A Combined Trend and Clustering Approach. Climate 2024, 12, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, Z.; Yang, G.; Zhong, Y.; Zhao, Y. Spatiotemporal Change Analysis and Future Scenario of LULC Using the CA-ANN Approach: A Case Study of the Greater Bay Area, China. Land 2021, 10, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saddique, N.; Mahmood, T.; Bernhofer, C. Quantifying the impacts of land use/land cover change on the water balance in the afforested River Basin, Pakistan. Environ. Earth Sci. 2020, 79, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engida, T.G.; Nigussie, T.A.; Aneseyee, A.B. Land Use/Land Cover Change Impact on Hydrological Process in the Upper Baro Basin, Ethiopia. Hindawi Appl. Environ. Soil Sci. 2021, 2021, 6617541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obahoundje, S.; Diedhiou, A. Potential impacts of climate, land use and land cover changes on hydropower generation in West Africa: A review. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 043005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, V.; Prasun, S.P.A.; Bhaskar, K.G. Assessment of land use land cover change impact on hydrological regime of a basin. Environ. Earth Sci. 2017, 76, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Wu, Y.; Wang, L.; Sun, P.; Zhao, F.; Jin, Z.; Wang, Y.; Qiu, L.; Lian, Y. Impacts of land-use conversions on the water cycle in a typical watershed in the southern Chinese Loess Plateau. J. Hydrol. 2021, 593, 125741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimbi, S.B.; Onodera, S.-I.; Wang, K.; Kaihotsu, I.; Shimizu, Y. Assessing the Impact of Urbanization and Climate Change on Hydrological Processes in a Suburban Catchment. Environments 2024, 11, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.H.; Botta, A.; Cardille, J.A. Effects of large-scale changes in land cover on the discharge of the Tocantins River, Southeastern Amazonia. J. Hydrol. 2003, 283, 206–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Long, D.; Zhao, Y.; Lu, H.; Hong, Y. Observed changes in flow regimes in the Mekong River basin. J. Hydrol. 2017, 551, 217–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, J.; Rustomji, P.; Hairsine, P. Responses of streamflow to changes in climate and land use/cover in the Loess Plateau, China. Water Resour. Res. 2014, 50, 3205–3220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnell, N.W.; Gosling, S.N. The impacts of climate change on river flow regimes at the global scale. J. Hydrol. 2016, 534, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronstert, A.; Niehoff, D.; Bürger, G. Effects of climate and land-use change on storm runoff generation: Present knowledge and modelling capabilities. Hydrol. Process. 2002, 16, 509–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaze, J.; Teng, J.; Chiew, F.H.S. Impact of climate change on runoff in the Murray-Darling Basin: A simulation study. Water Resour. Res. 2011, 47, W00G10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feyen, L.; Dankers, R. Impact of global warming on streamflow drought in Europe. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2009, 114, D17116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanlon, B.R.; Keese, K.E.; Flint, A.L.; Flint, L.E.; Gaye, C.B.; Edmunds, W.M.; Simmers, I. Global synthesis of groundwater recharge in semiarid and arid regions. Hydrol. Process. 2006, 20, 3335–3370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.Q.; Zhang, J.Y.; Jin, J.L.; Pagano, T.C.; Calow, R.; Bao, Z.X.; Liu, C.S.; Liu, Y.L.; Yan, X.L. Assessing water resources in China using PRECIS projections and a VIC model. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2012, 22, 231–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubiak-Wójcicka, K.; Piątkowski, K.; Juśkiewicz, W.W. Lake surface changes of the Osa River catchment, (northern Poland), 1900–2010. J. Maps 2021, 17, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Bretz, M.; Dewan, M.M.A.; Delavar, M.A. Machine learning in modelling land-use and land cover-change (LULCC): Current status, challenges and prospects. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 822, 153559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, S.; Meshesha, T.W.; Sen, I.S.; Bol, R.; Bogena, H.; Wang, J. Assessing Impacts of Land Use and Land Cover (LULC) Change on Stream Flow and Runoff in Rur Basin, Germany. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barati, A.A.; Zhoolideh, M.; Azadi, H.; Ju-Hyoung Lee, J.-H.; Scheffran, J. Interactions of land-use cover and climate change at global level: How to mitigate the environmental risks and warming effects. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 146, 109829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, J.; Oreskes, N.; Doran, P.T.; Anderegg, W.R.L.; Verheggen, B.; Maibach, E.W.; Carlton, J.S.; Lewandowsky, S.; Skuce, A.G.; Green, S.; et al. Consensus on consensus: A synthesis of consensus estimates on human-caused global warming. Environ. Res. Lett. 2016, 11, 048002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.; Verma, M.K.; Prasad, A.D.; Mehta, D.; Azamathulla, H.M.; Muttil, N.; Rathnaynake, U. Simulating the Hydrological Processes under Multiple Land Use/Land Cover and Climate Change Scenarios in the Mahanadi Reservoir Complex, Chhattisgarh, India. Water 2023, 15, 3068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardhani, F.A.; Pravitasari, A.E.; Ridwansyah, I. Flash flood assessment at Upper Cisadane Watershed using land use/land cover and morphometric factors. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2022; Volume 1109, p. 012002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniawan, T.A.; Bandala, E.R.; Othman, M.H.D.; Goh, H.H.; Anouzlae, A.; Chewf, K.W.; Aziz, F.; Al-Hazm, H.E.; Nisa’ulKhoir, A. Implications of climate change on water quality and sanitation in climate hotspot locations: A case study in Indonesia. Water Supply 2024, 24, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umami, A.; Sukmana, H.; Wikurendra, E.A.; Paulik, E. A review on water management issues: Potential and challenges in Indonesia. Sustain. Water Resour. Manag. 2022, 8, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anggraheni, E.; Hamdany, A.H.; Maricar, F.; Andika, N.; Sisinggih, D.; Tanlie, F.S.; Respati, F.A.R. Hydrological Response of Land Use and Climate Change Impact on Sediment Rate in Upper Citarum Watershed. Fluids 2025, 10, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gradiyanto, F.; Parmantoro, P.N.; Suharyanto. Impact of climate change on Kupang River flow and hydrological extremes in Greater Pekalongan, Indonesia. Water Sci. Eng. 2025, 18, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranata, K.A.; Aji, A. Analisis Spasial Tingkat Potensi Kekeringan dan Tingkat Kesiapsiagaan Masyarakat dalam Menghadapi Bencana Kekeringan di Kabupaten Grobogan. Indones. J. Conserv. 2021, 10, 108–114. [Google Scholar]

- Ikhwali, M.F.; Pawattana, C.; Nur, S.; Azhari, B.; Ikhsan, M.; Aida, N.; Silvia, C.S. Reviews, challenges, and prospects of the application of Hydrologic Engineering Center-Hydrologic Modelling System (HEC-HMS) model in Indonesia. Eng. Appl. Sci. Res. 2022, 49, 669–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avia, L.Q. Change in rainfall per-decades over Java Island, Indonesia. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanto; Livneh, B.; Rajagopalan, B.; Kasprzyk, J. Hydrological model application under data scarcity for multiple watersheds, Java Island, Indonesia. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2017, 9, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratiwi, E.P.A.; Ramadhani, E.L.; Nurrochmad, F.; Legono, D. The Impacts of Flood and Drought on Food Security in Central Java. J. Civ. Eng. Forum 2020, 6, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prihestiwi, R.C.; Handayani, W.; Sarasadi, A. Land Use and Surface Runoff Change in Babon Watershed Semarang Greater Area. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, D. Urban growth simulation of Atakum (Samsun, Turkey) using cellular automata-Markov chain and Multi-layer Perceptron-Markov chain models. Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 5918–5950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukesh, K.; Shiva Nagendra, S.M. Artificial Neural Networks in Vehicular Pollution Modelling; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; 242p. [Google Scholar]

- Eastman, J.R. IDRISI Selva Tutorial. Worcester: IDRISI Production, Clark Labs-Clark University. 2015. Available online: http://uhulag.mendelu.cz/files/pagesdata/eng/gis/idrisi_selva_tutorial.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Hanafi, F. Kajian perubahan penggunaan lahan terhadap laju erosi permuka an di daerah tangkapan air waduk mrica. J. Geogr. Media Inf. Pengemb. Ilmudan Profesi Kegeografian 2015, 12, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- BBWS Pemali Juana. Profil BBWS Pemali Juana. 2022. Available online: https://sda.pu.go.id/balai/bbwspemalijuana/pages/profil_bbwspj (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Rahadeyani, R.D.; Johanes Kodoatie, R.J.; Atmodjo, P.S. Strategi Penanganan Aspek Non Teknis Dalam Infrastruktur Saluran Air Baku Klambu-Kudu. Briliant J. Ris. Konseptual 2020, 5, 591–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwanta, S.; Abdulgani, H. Penyusunan Penilaian Kinerja Dan Angka Kebutuhan Nyata Operasi Dan Pemeliharaan (AKNOP) Daerah Irigasi Klambu. J. Rekayasa Infrastruktur 2021, 7, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Synthesis Report, Summary for Policymakers. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Core Writing Team, Lee, H., Romero, J., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/syr/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_SYR_SPM.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Julianto, F.D.; Ediyanto, I. Analisis Sebaran Potensi Kekeringan Dengan Cloud Computing Platform di Kabupaten Grobogan. J. Ilm. Tek. Geomatika IMAGI 2021, 1, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanafi, F.; Rahmadewi, D.P.; Setiawan, F. Land Cover Changes Based on Cellular Automata for Land Surface Temperature in Semarang Regency. Geosfera Indones. 2021, 6, 301–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paredes-Trejo, F.J.; Barbosa, H.A.; Lakshmi Kumar, T.V. Validating CHIRPS-based satellite precipitation estimates in Northeast Brazil. J. Arid Environ. 2017, 139, 26–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y.; Roy, D.P.; Martins, V.S.; Zhang, H.K.; Yan, L.; Li, Z. Conterminous United States Landsat-8 top of atmosphere and surface reflectance tasseled cap transformation coefficients. Remote Sens. Environ. 2022, 274, 112992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foody, G.M. Explaining the unsuitability of the kappa coefficient in the assessment and comparison of the accuracy of thematic maps obtained by image classification. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 15, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susetyo, D.B. Vertical accuracy assessment of various open-source DEM data: DEMNAS, SRTM-1, AND ASTER GDEM. Geod. Cartogr. 2023, 49, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walley, Y.; Henshaw, A.J.; Brasington, J. Topological structures of river networks and their regional-scale controls: A multivariate classification approach. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2020, 45, 2869–2883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertanian, B.B.S.D.L. Sifat Fisik Tanah dan Metode Analisisnya; Departement Pertanian: Bogor, Indonesia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Trajkovic, S.; Gocic, M.; Pongracz, R.; Bartholy, J. Adjustment of Thornthwaite equation for estimating evapotranspiration in Vojvodina. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2019, 138, 1231–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramono, I.; Budiastuti, M.; Gunawan, T.; Wiryanto. Water Yield Analysis on Area Covered by Pine Forest at Kedungbulus Watershed Central Java, Indonesia. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Eng. Inf. Technol. 2017, 7, 943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakim, R. Analysis of the influence of environmental behaviour on the water balance of Kaligarang watershed, Central Java. Int. J. Disaster Dev. Interface 2024, 4, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, A.; Lin, Y.P.; Lur, H.S. Evaluating and adapting climate change impacts on rice production in Indonesia: A case study of the Keduang subwatershed, Central Java. Environments 2021, 1, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Sánchez, J.; Senent-Aparicio, J.; Segura-Méndez, F.; Pulido-Velazquez, D.; Srinivasan, R. Evaluating Hydrological Models for Deriving Water Resources in Peninsular Spain. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mammoliti, E.; Fronzi, D.; Mancini, A.; Valigi, D.; Tazioli, A. Water balANce, a WebApp for Thornthwaite–Mather Water Balance Computation: Comparison of Applications in Two European Watersheds. Hydrology 2021, 8, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sishu, F.K.; Seifu, A.; Tilahun, S.A.; Schmitter, P.; Steenhuis, T.S. Revisiting the Thornthwaite Mather procedure for baseflow and groundwater storage predictions in sloping and mountainous regions. J. Hydrol. X 2024, 24, 100179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrayana, H.; Widyastuti, M.; Riyanto, I.A.; Nuha, A.; Widasmara, M.Y.; Ismayuni, N.; Rachmi, I.N. Thornthwaite and Mather water balance method in Indonesian Tropical Area. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2021; Volume 851, p. 012011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmate, S.S.; Wagner, P.D.; Fohrer, N.; Pandey, A. Assessment of Uncertainties in Modelling Land Use Change with an Integrated Cellular Automata–Markov Chain Model. Environ. Model. Assess. 2022, 27, 275–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naderi, M.; Ardeh, F.T.; Abedi, F.; Masoumi, Z. Impact of land-use and climate change on future extreme flows: A study for three dam watersheds in Alborz and Tehran provinces of Iran. Appl. Water Sci. 2025, 15, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type | Station | Elevation (msl) | Research Data (Years) | Temporal Data Quality | Missing Data (Number Of Years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rainfall | Rawa Pening | 358.26 | 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015, 2020 | 40% | 2000, 2005 and 2020 |

| Rainfall | Kedung Ombo | 358.26 | 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015, 2020 | 0% | 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015 and 2020 |

| Rainfall | Prawoto | 110.1 | 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015, 2020 | 20% | 2000, 2005, 2010 and 2020 |

| Rainfall | Tempuran | 98.2 | 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015, 2020 | 20% | 2000, 2005, 2010 and 2015 |

| Rainfall | BKSDA B SOLO | 358.26 | 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015, 2020 | 80% | 2000 |

| Rainfall | Greneng | 98.2 | 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015, 2020 | 20% | 2000, 2005, 2010 and 2015 |

| Temperatures | Semarang/Salatiga | 283 | 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015, 2020 | 40% | 2000, 2005 and 2010 |

| Temperatures | Ungaran | 358.26 | 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015, 2020 | 40% | 2000, 2005 and 2010 |

| Temperatures | Pati | 98.2 | 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015, 2020 | 40% | 2000, 2005 and 2010 |

| Temperatures | Purwodadi/Grobogan | 57 | 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015, 2020 | 40% | 2000, 2005 and 2010 |

| Discharge | Klambu DAM | 57 | 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015, 2020 | 33% | 2000, Feb & Sep 2005, and May–Oct 2015 |

| Parameters | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | ||||||||||||

| ΣP (mm) | 229.7 | 244.8 | 321.4 | 253.3 | 101.0 | 232.5 | 68.9 | 51.3 | 113.0 | 185.3 | 219.1 | 275.5 |

| Tav (°C) | 27.9 | 28.0 | 28.3 | 28.0 | 28.8 | 28.4 | 27.9 | 28.3 | 28.6 | 28.8 | 28.4 | 27.7 |

| ΣQ (m3) | 143.8 | 117.2 | 90.6 | 173.3 | 18.9 | 33.6 | 20.6 | 13.9 | 18.2 | 22.6 | 43.9 | 107.4 |

| 2010 | ||||||||||||

| ΣP (mm) | 354.0 | 280.6 | 362.2 | 166.8 | 181.6 | 103.0 | 95.6 | 83.8 | 317.6 | 199.2 | 203.4 | 297.0 |

| Tav (°C) | 28.2 | 28.4 | 28.8 | 28.2 | 28.0 | 27.7 | 27.8 | 28.8 | 28.0 | 28.0 | 27.9 | 26.9 |

| ΣQ (m3) | 106.4 | 94.2 | 103.3 | 80.0 | 116.8 | 42.0 | 17.6 | 16.5 | 52.7 | 62.6 | 68.1 | 160.2 |

| 2015 | ||||||||||||

| ΣP (mm) | 261.3 | 430.9 | 342.9 | 327.2 | 119.7 | 31.5 | 6.3 | 12.4 | 2.9 | 29.2 | 233.0 | 266.8 |

| Tav (°C) | 27.7 | 28.3 | 28.4 | 28.6 | 28.7 | 28.4 | 28.8 | 29.1 | 28.8 | 28.0 | 28.3 | 28.1 |

| ΣQ (m3) | 114.9 | 145.2 | 145.2 | 204.8 | 134.1 | 12.9 | 12.4 | 12.9 | 13.4 | 10.9 | 41.0 | 138.8 |

| 2020 | ||||||||||||

| ΣP (mm) | 339.7 | 429.3 | 352.4 | 227.5 | 188.9 | 34.6 | 110.4 | 49.2 | 78.2 | 163.6 | 249.8 | 411.5 |

| Tav (°C) | 28.0 | 27.8 | 28.5 | 28.9 | 28.3 | 28.3 | 27.6 | 27.6 | 28.4 | 28.0 | 28.9 | 27.6 |

| ΣQ (m3) | 131.9 | 205.6 | 84.2 | 154.3 | 11.4 | 14.2 | 14.2 | 14.1 | 14.0 | 3.3 | 68.0 | 229.1 |

| No | Land Cover | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | 2020 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Water Body | 51.8 | 24.2 | 37.1 | 55.2 | 28.4 | 39.5 |

| 2 | Forest | 523.2 | 422.8 | 634.1 | 408.2 | 107.5 | 137.2 |

| 3 | Rice Field | 1091.7 | 1122.7 | 442.9 | 997.7 | 1034.2 | 1014.1 |

| 4 | Dry Agriculture | 748.2 | 503.0 | 1045.8 | 627.7 | 1217.3 | 807.4 |

| 5 | Open Land | 16.7 | 60.8 | 87.0 | 46.0 | 41.3 | 64.3 |

| 6 | Built Area | 497.0 | 209.7 | 374.5 | 436.8 | 167.0 | 319.0 |

| 7 | Diversified Farm | 117.0 | 702.5 | 424.3 | 474.1 | 449.9 | 664.4 |

| Sums | 3045.7 | 3045.7 | 3045.7 | 3045.7 | 3045.7 | 3045.7 |

| Years | Discharge (m3·s−1) | Pearson | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | Q TWM | 8.37 | 0.644661 |

| Q Obs | 66.99 | ||

| 2010 | Q TWM | 126.01 | 0.702479 |

| Q Obs | 76.70 | ||

| 2015 | Q TWM | 93.52 | 0.943908 |

| Q Obs | 82.22 | ||

| 2020 | Q TWM | 67.05 | 0.572959 |

| Q Obs | 78.68 | ||

| Parameters | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P (mm) | 339.71 | 387.61 | 330.04 | 266.44 | 152.97 | 59.97 | 43.44 | 44.23 | 80.15 | 167.07 | 219.1 | 275.5 |

| T (°C) | 27.92 | 28.20 | 28.56 | 28.62 | 28.48 | 28.48 | 28.36 | 29.10 | 29.24 | 29.40 | 28.26 | 27.61 |

| Lat | −7.20 | −7.20 | −7.20 | −7.20 | −7.20 | −7.20 | −7.20 | −7.20 | −7.20 | −7.20 | −7.20 | −7.20 |

| Rad | −0.13 | −0.13 | −0.13 | −0.13 | −0.13 | −0.13 | −0.13 | −0.13 | −0.13 | −0.13 | −0.13 | −0.13 |

| I | 354.0 | 280.6 | 362.2 | 166.8 | 181.6 | 103.0 | 95.6 | 83.8 | 317.6 | 199.2 | 203.4 | 297.0 |

| ƩI | 28.2 | 28.4 | 28.8 | 28.2 | 28.0 | 27.7 | 27.8 | 28.8 | 28.0 | 28.0 | 27.9 | 26.9 |

| a | 4.50 | 4.50 | 4.50 | 4.50 | 4.50 | 4.50 | 4.50 | 4.50 | 4.50 | 4.50 | 4.50 | 4.50 |

| f | 1.07 | 0.95 | 1.04 | 1.00 | 1.02 | 0.99 | 1.02 | 1.03 | 1.00 | 1.05 | 1.03 | 1.06 |

| EP | 159.35 | 166.70 | 176.51 | 178.08 | 174.44 | 174.21 | 174.13 | 191.95 | 196.11 | 201.23 | 168.29 | 151.66 |

| Epx | 170.32 | 158.38 | 183.57 | 178.08 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 173.33 | 160.75 |

| P-EP cor | 169.39 | 220.23 | 146.47 | 88.36 | −24.96 | −112.50 | −131.11 | −153.48 | −115.96 | −44.22 | 238.66 | 93.45 |

| surplus | 170.32 | 158.38 | 183.57 | 178.08 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 173.33 | 160.75 |

| Deficit | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −24.96 | −112.50 | −131.11 | −153.48 | −115.96 | −44.22 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| WHC/STO | 138.76 | 138.76 | 138.76 | 138.76 | 138.76 | 138.76 | 138.76 | 138.76 | 138.76 | 138.76 | 138.76 | 138.76 |

| e = 2.7182818284 | 2.72 | 2.72 | 2.72 | 2.72 | 2.72 | 2.72 | 2.72 | 2.72 | 2.72 | 2.72 | 2.72 | 2.72 |

| S/D | 170.32 | 158.38 | 183.57 | 178.08 | −24.96 | −112.50 | −131.11 | −153.48 | −115.96 | −44.222 | 173.33 | 160.75 |

| APWL | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −24.96 | −137.46 | −268.57 | −422.05 | −538.01 | −582.24 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| ΔSt | 138.76 | 138.76 | 138.76 | 138.76 | 129.58 | 88.19 | 39.96 | −16.50 | −59.16 | −75.43 | 138.76 | 138.76 |

| EA | 170.32 | 158.38 | 183.57 | 178.08 | 282.55 | 148.16 | 83.39 | 27.73 | 20.98 | 91.64 | 173.33 | 160.75 |

| RO | 191.26 | 201.94 | 215.03 | 224.86 | 143.00 | 59.63 | 24.87 | 10.37 | 4.32 | 1.80 | 82.94 | 158.72 |

| Years | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Pearson |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 191.26 | 201.94 | 215.03 | 224.86 | 143.00 | 59.63 | 24.87 | 10.37 | 4.32 | 1.80 | 82.94 | 158.72 | 0.952 |

| 2005 | 148.67 | 154.66 | 160.30 | 166.34 | 105.99 | 44.20 | 18.43 | 7.69 | 3.20 | 73.09 | 137.31 | 154.62 | 0.854 |

| 2010 | 169.43 | 182.04 | 184.68 | 185.37 | 182.47 | 114.04 | 47.55 | 19.83 | 70.92 | 131.11 | 159.00 | 164.48 | 0.802 |

| 2015 | 194.49 | 202.26 | 213.21 | 222.40 | 141.81 | 59.14 | 24.66 | 10.28 | 4.29 | 1.79 | 83.19 | 165.32 | 0.951 |

| 2020 | 196.25 | 199.89 | 210.15 | 225.35 | 227.74 | 143.14 | 59.69 | 24.89 | 10.38 | 4.33 | 93.21 | 168.48 | 0.886 |

| 2030 | 203.41 | 188.62 | 205.81 | 223.74 | 143.16 | 59.70 | 24.89 | 10.38 | 4.33 | 1.81 | 96.01 | 190.98 | 0.947 |

| 2040 | 237.77 | 218.91 | 239.86 | 161.52 | 67.35 | 28.09 | 11.71 | 4.88 | 2.04 | 0.85 | 112.68 | 224.78 | 0.812 |

| Years | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scenario C 3, 4 | ||||||||||||

| 2025 | wet | wet | wet | wet | dry | dry | dry | dry | dry | dry | wet | wet |

| 2030 | wet | wet | wet | dry | dry | dry | dry | dry | dry | dry | wet | wet |

| 2035 | wet | wet | wet | dry | dry | dry | dry | dry | dry | dry | wet | wet |

| 2040 | wet | wet | dry | dry | dry | dry | dry | dry | dry | dry | dry | wet |

| Scenario C 5 | ||||||||||||

| 2025 | wet | wet | wet | wet | dry | dry | dry | dry | dry | dry | wet | wet |

| 2030 | wet | wet | wet | dry | dry | dry | dry | dry | dry | dry | wet | wet |

| 2035 | wet | wet | wet | dry | dry | dry | dry | dry | dry | dry | wet | wet |

| 2040 | wet | wet | dry | dry | dry | dry | dry | dry | dry | dry | dry | wet |

| Scenario C 6 | ||||||||||||

| 2025 | wet | wet | wet | wet | dry | dry | dry | dry | dry | dry | wet | Wet |

| 2030 | wet | wet | wet | dry | dry | dry | dry | dry | dry | dry | wet | wet |

| 2035 | wet | wet | dry | dry | dry | dry | dry | dry | dry | dry | dry | Wet |

| 2040 | wet | wet | dry | dry | dry | dry | dry | dry | dry | dry | dry | wet |

| Scenario C 7, 8 | ||||||||||||

| 2025 | wet | wet | wet | wet | dry | dry | dry | dry | dry | dry | wet | wet |

| 2030 | wet | wet | wet | dry | dry | dry | dry | dry | dry | dry | dry | wet |

| 2035 | wet | wet | dry | dry | dry | dry | dry | dry | dry | dry | dry | dry |

| 2040 | dry | wet | dry | dry | dry | dry | dry | dry | dry | dry | dry | dry |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hanafi, F.; Wijayanti, L.A.; Ramadhan, M.F.; Priakusuma, D.; Kubiak-Wójcicka, K. Impact of Climate and Land Cover Dynamics on River Discharge in the Klambu Dam Catchment, Indonesia. Water 2026, 18, 250. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020250

Hanafi F, Wijayanti LA, Ramadhan MF, Priakusuma D, Kubiak-Wójcicka K. Impact of Climate and Land Cover Dynamics on River Discharge in the Klambu Dam Catchment, Indonesia. Water. 2026; 18(2):250. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020250

Chicago/Turabian StyleHanafi, Fahrudin, Lina Adi Wijayanti, Muhammad Fauzan Ramadhan, Dwi Priakusuma, and Katarzyna Kubiak-Wójcicka. 2026. "Impact of Climate and Land Cover Dynamics on River Discharge in the Klambu Dam Catchment, Indonesia" Water 18, no. 2: 250. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020250

APA StyleHanafi, F., Wijayanti, L. A., Ramadhan, M. F., Priakusuma, D., & Kubiak-Wójcicka, K. (2026). Impact of Climate and Land Cover Dynamics on River Discharge in the Klambu Dam Catchment, Indonesia. Water, 18(2), 250. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020250