Tracing the Origin of Groundwater Salinization in Multilayered Coastal Aquifers Using Geochemical Tracers

Abstract

1. Introduction

Study Area

- Holocene: Consists of unconsolidated coastal sand dunes forming an unconfined porous aquifer parallel to the coast, with thickness exceeding 50 m in some areas. This unit shows hydraulic conductivities between 10 and 30 m day−1, groundwater level depth between 2 and 4 m, and it is mainly recharged by direct infiltration of precipitation.

- Undifferentiated Plio-Pleistocene: Composed of fine- to medium-grained sands with conglomeratic horizons and clay intercalations. Thickness ranges from less than 20 m close to São Pedro de Moel to more than 150 m towards southeast. Hydraulic conditions vary from semi-confined to confined.

- Miocene: Formed by clayey sandstones, conglomerates and calcareous concretions. Hydraulic conditions vary from unconfined in the eastern outcrop areas to confined westward below the undifferentiated Plio-Pleistocene clayey layers. Recharge occurs through direct infiltration of precipitation in elevated eastern areas and through interactions with surface water.

- Early Cretaceous (Aptian–Albian): Confined to semi-confined unit composed of sandstones and carbonate complexes underlying the Miocene formations. Although it does not outcrop within the study area, recharge occurs through eastern outcrops and along fault zones.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sampling and Analytical Methods

2.1.1. Rainwater

- Local Meteoric Water Line (LMWL) determination

2.1.2. Groundwater

3. Results and Discussion

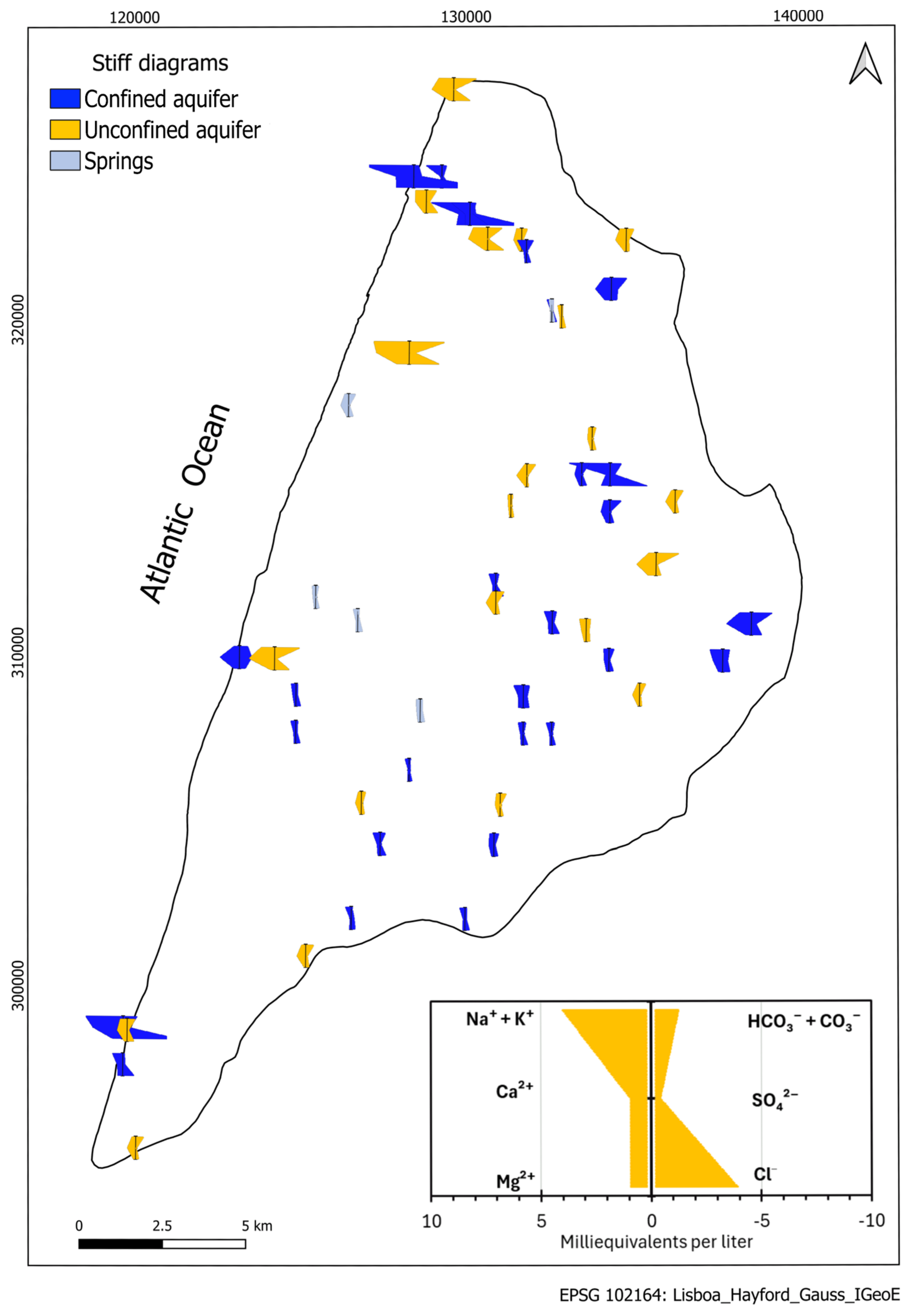

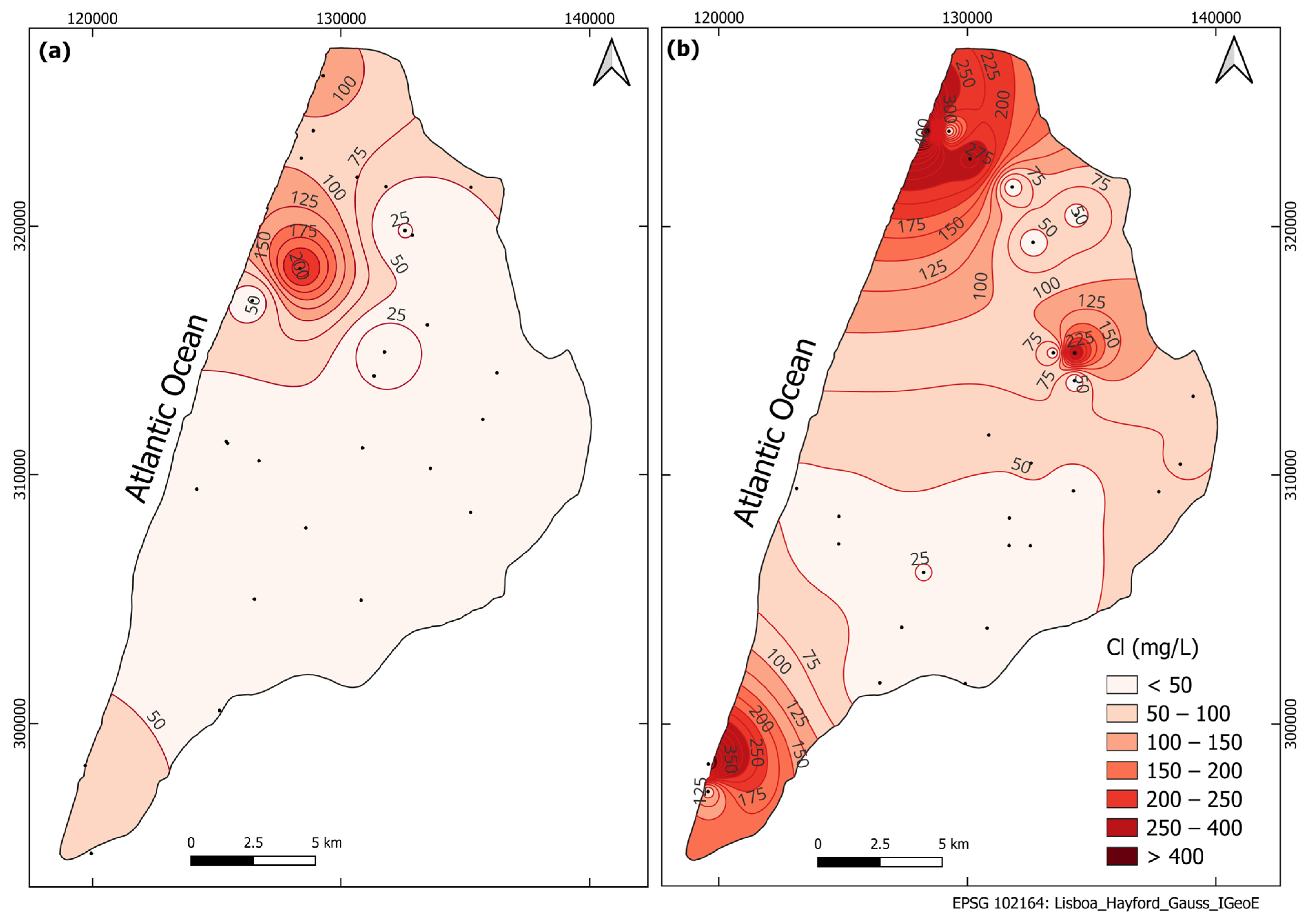

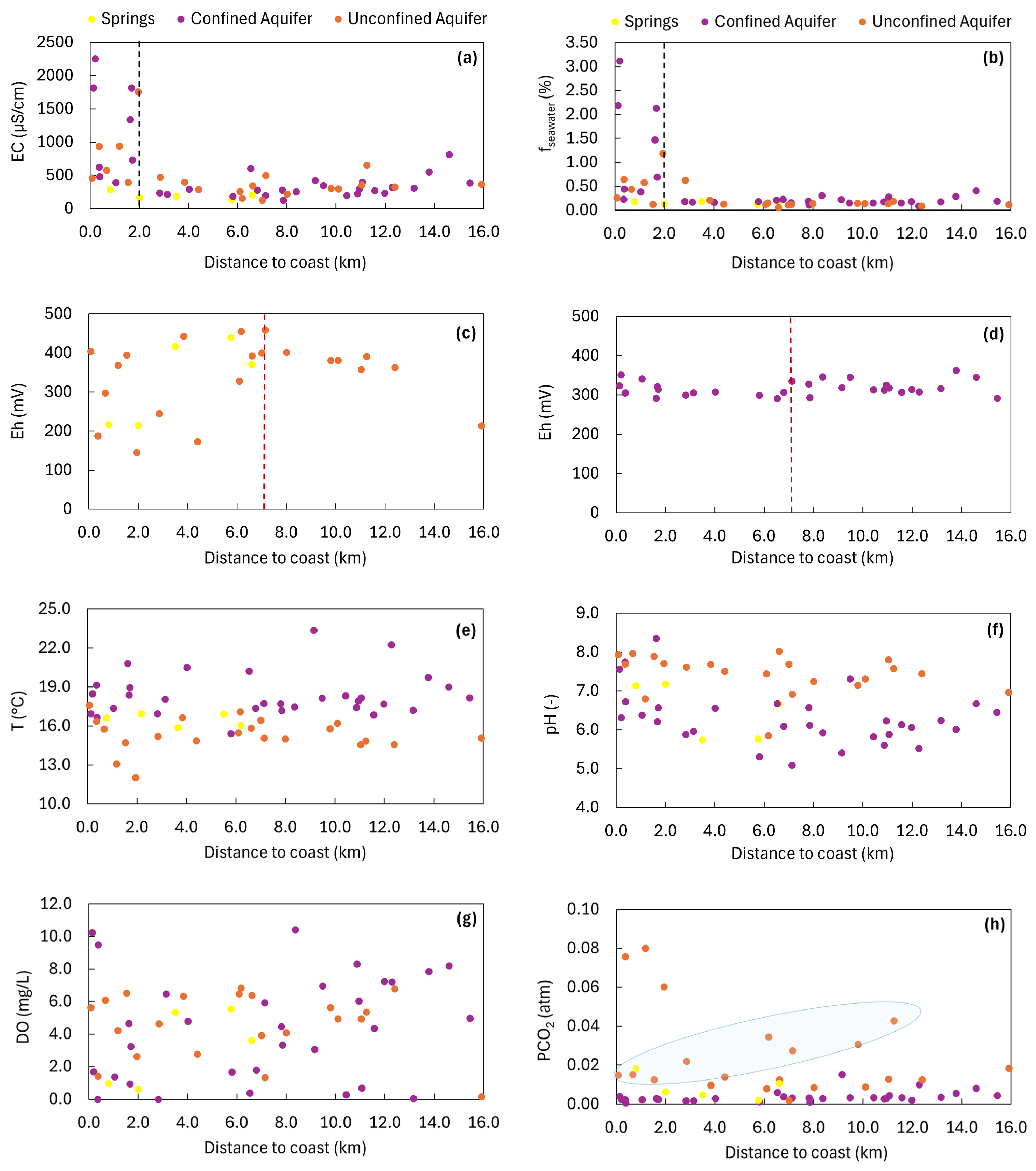

3.1. Hydrochemical Characterization

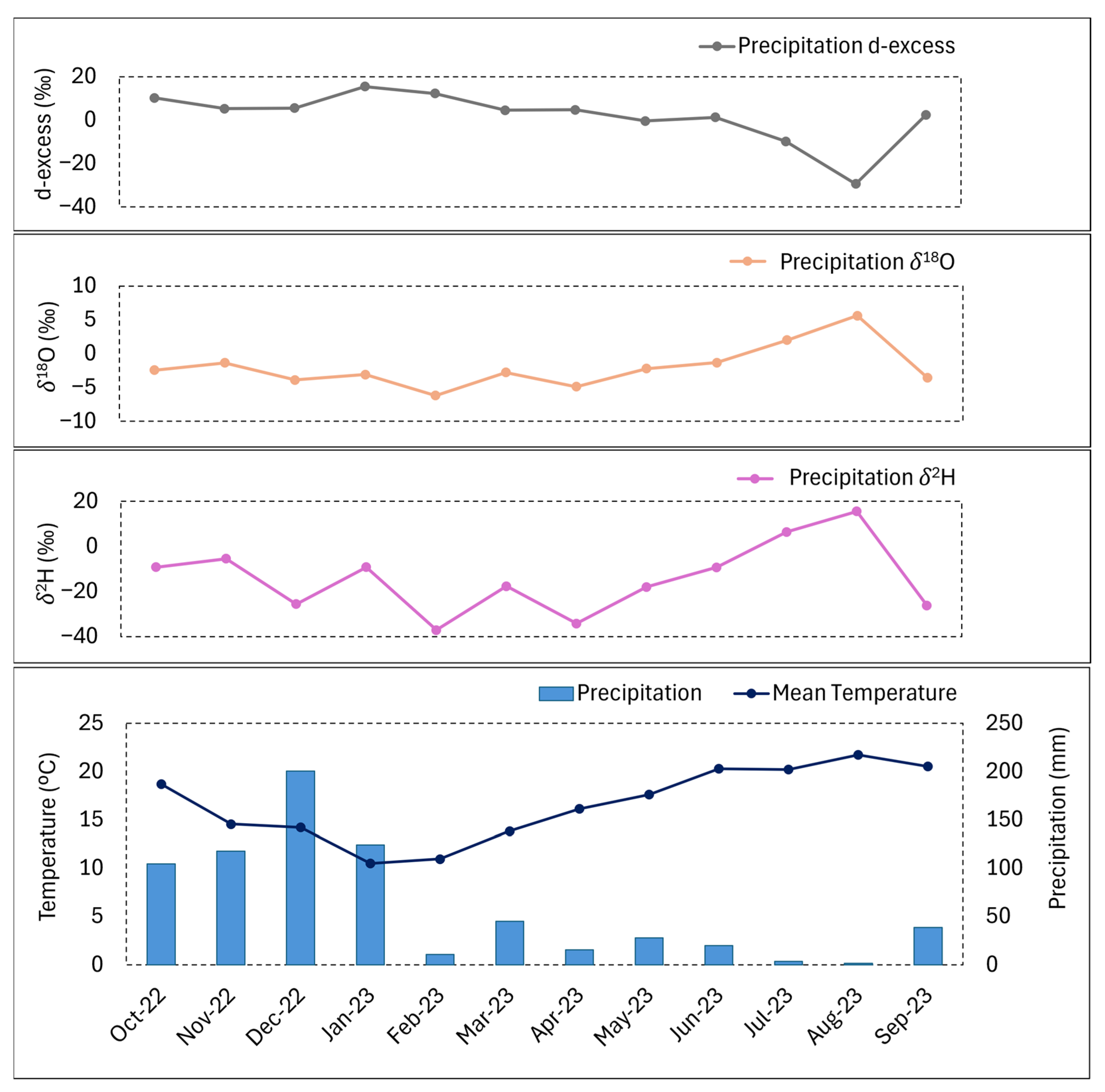

3.1.1. Rainwater Characterization

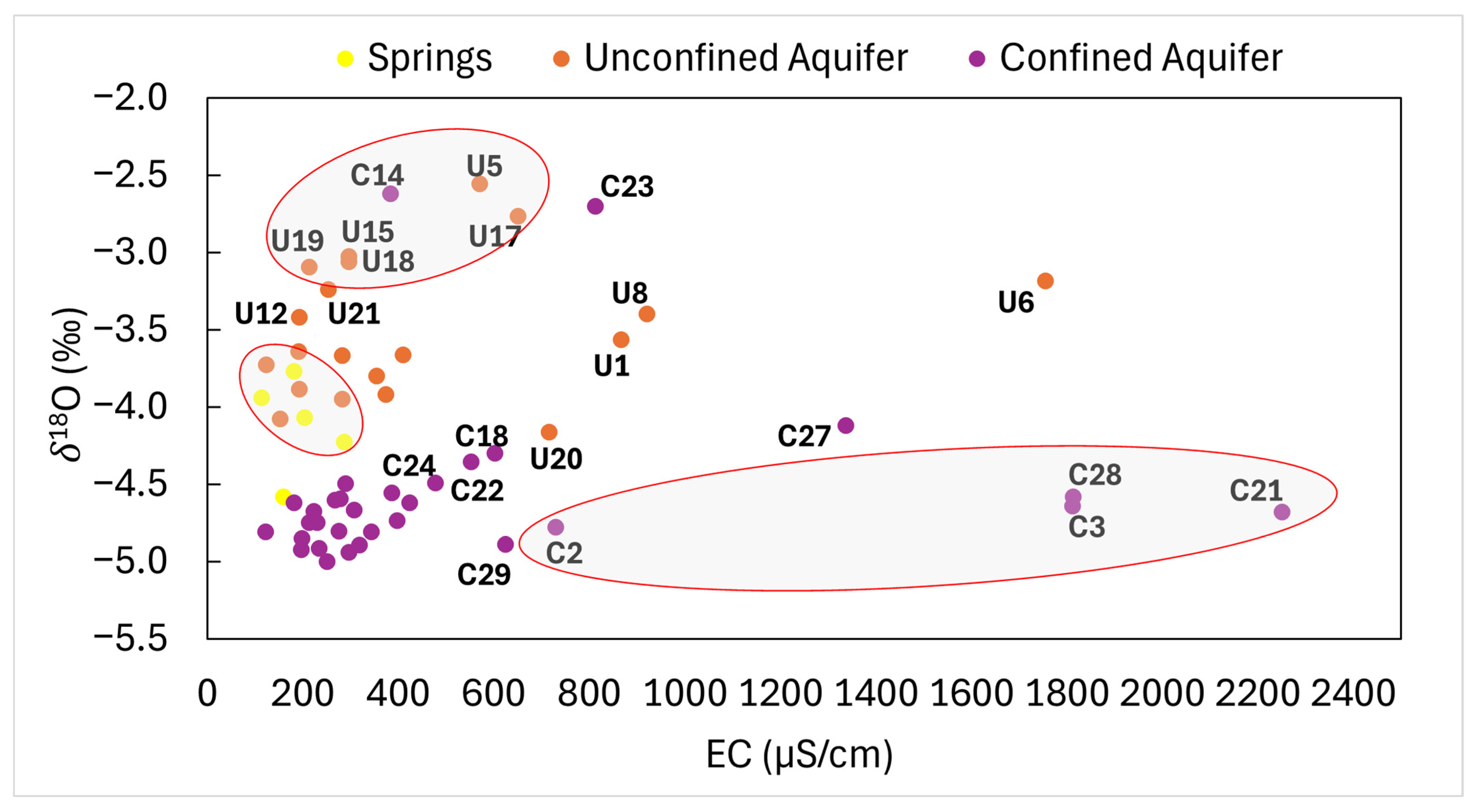

3.1.2. Groundwater Characterization

- Minor and trace elements in the aquifer

3.2. Isotopic Characterization

3.2.1. Rainwater

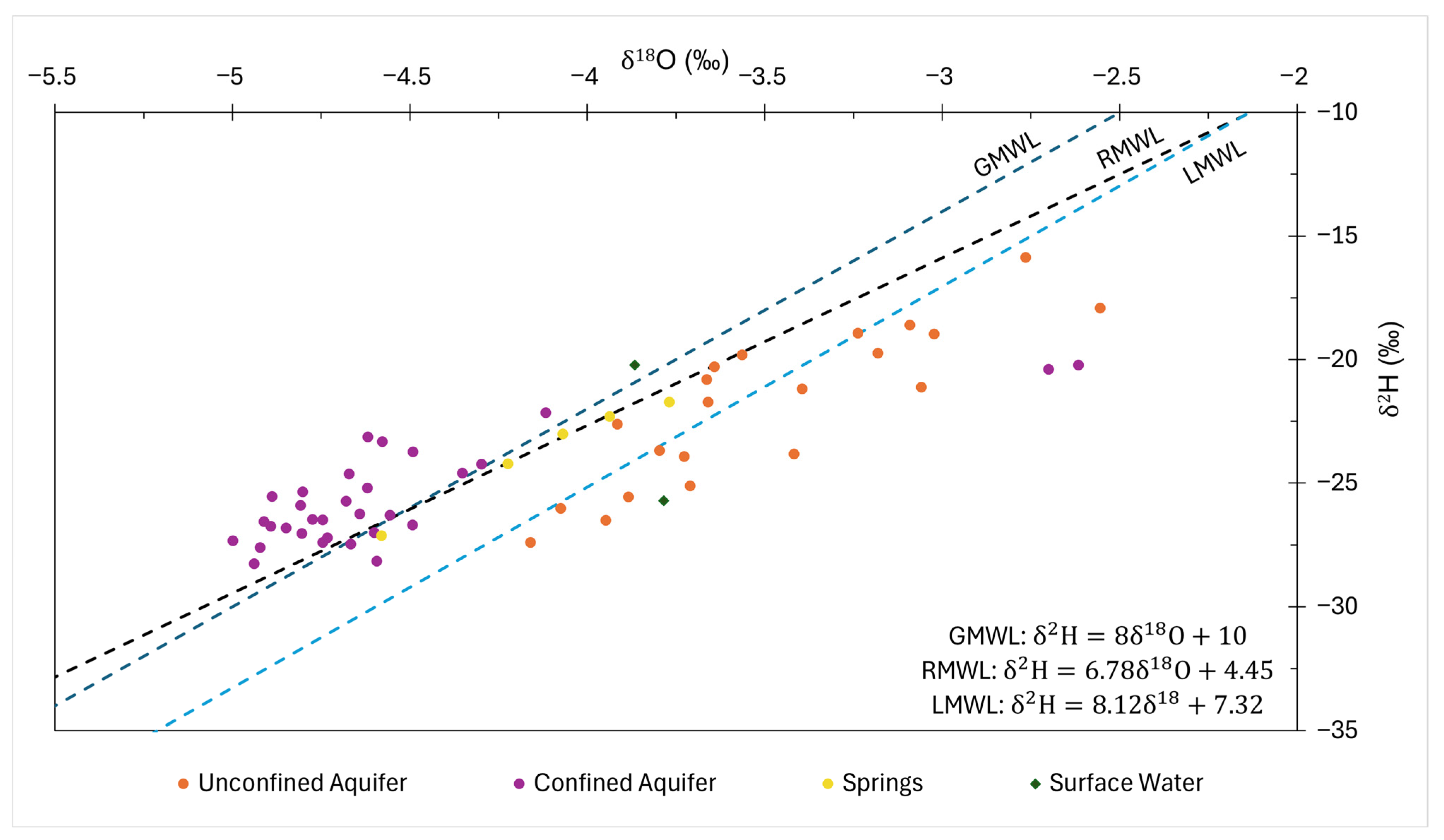

3.2.2. Surface and Groundwater

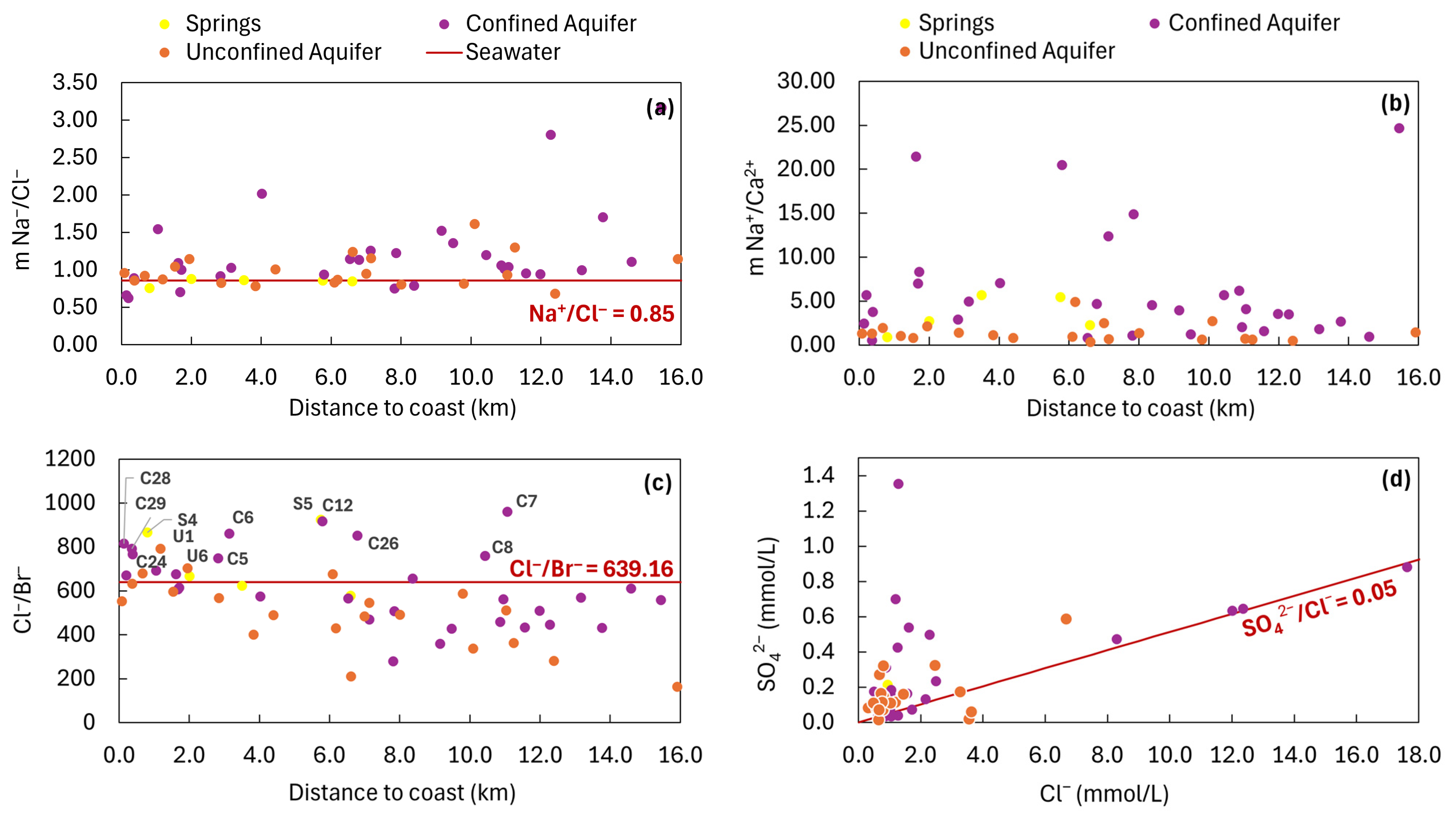

3.3. Groundwater Salinity Sources

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DO | Dissolved Oxygen |

| EC | Electrical Conductivity |

| PCO2 | Parcial CO2 pressure |

| OLS | Ordinary Least Squares Regression |

| RMA | Reduced Major Axis Regression |

| PWLS | Precipitation Weighted Least Squares Regression |

| RSP | São Pedro de Moel stream |

| LMWL | Local Meteoric Water Line |

| RMWL | Regional Meteoric Water Line |

| GMWL | Global Meteoric Water Line |

References

- Diamond, R.E. Stable Isotope Hydrology; Kalin, R., Poeter, E., Cherry, J., Eds.; The Groundwater Project: Guelph, ON, Canada, 2022; ISBN 978-1-77470-043-3. [Google Scholar]

- El Ouali, A.; Roubil, A.; Lahrach, A.; El Hmaidi, A.; El Ouali, A.; Ousmana, H.; Bouchaou, L. Assessments of Groundwater Recharge Process and Residence Time Using Hydrochemical and Isotopic Tracers under Arid Climate: Insights from Errachidia Basin (Central-East Morocco). Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 25, 101145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoni, S.; Huneau, F.; Garel, E.; Celle-Jeanton, H. Multiple Recharge Processes to Heterogeneous Mediterranean Coastal Aquifers and Implications on Recharge Rates Evolution in Time. J. Hydrol. 2018, 559, 669–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, H.F.; Lee, J.W. Stable Hydrogen and Oxygen Isotopes for Groundwater Sources of Penghu Islands, Taiwan. Geosciences 2018, 8, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eid, M.H.; Eissa, M.; Mohamed, E.A.; Ramadan, H.S.; Czuppon, G.; Kovács, A.; Szűcs, P. Application of Stable Isotopes, Mixing Models, and K-Means Cluster Analysis to Detect Recharge and Salinity Origins in Siwa Oasis, Egypt. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 25, 101124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paíz, R.; Low-Calle, J.F.; Molina-Estrada, A.G.; Gil-Villalba, S.; Condesso de Melo, M.T. Combining Spectral Analysis and Geochemical Tracers to Investigate Surface Water–Groundwater Interactions: A Case Study in an Intensive Agricultural Setting (Southern Guatemala). Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 899, 165578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Liu, H.; Zu, P.; Xu, W.; Su, X. Evaluation of the Influence of River Bank Infiltration on Groundwater in an Inland Alluvial Fan Using Spectral Analysis and Environmental Tracers. Hydrogeol. J. 2021, 29, 1117–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastoe, C.J. Isotope Record of Groundwater Recharge Mechanisms and Climate Change in Southwestern North America. Appl. Geochem. 2023, 151, 105604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araguás-Araguás, L.; Gonfiantini, R. Environmental Isotopes in Sea Water Intrusion Studies; IAEA: Vienna, Austria, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Carreira, P.M.; Marques, J.M.; Nunes, D. Source of Groundwater Salinity in Coastline Aquifers Based on Environmental Isotopes (Portugal): Natural vs. Human Interference. A Review and Reinterpretation. Appl. Geochem. 2014, 41, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallström, J. Groundwater Quality Constraints in the Vieira de Leiria-Marinha Grande Aquifer: Implications for Further Development under Global Changes. Master’s Thesis, Instituto Superior Técnico, Lisbon, Portugal, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zbyszewski, G.; Torre de Assunção, C. Notícia Explicativa da Folha 22-D—Marinha Grande. In Carta Geológica de Portugal na Escala de 1/50 000; Laboratório Nacional de Energia e Geologia: Amadora, Portugal, 1965; pp. 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, C.; Mendonça, J.J.L.; Jesus, M.R.; Gomes, A.J. Sistemas Aquíferos de Portugal Continental; Centro de Geologia da Universidade de Lisboa & Instituto Nacional da Água: Lisbon, Portugal, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Dias, P.A.C. Modelação Estrutural e Gravimétrica da Estrutura Salífera de Monte Real (Leiria, Portugal). Master’s Thesis, Universidade de Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kullberg, J.C.R.; Rocha, R.B.; Soares, A.F.; Rey, J.; Terrinha, P.; Azerêdo, A.C.; Callapez, P.; Duarte, L.V.; Kullberg, M.C.; Martins, L.; et al. A Bacia Lusitaniana: Estratigrafia, Paleogeografia e Tectónica. In Geologia de Portugal: Geologia Meso-Cenozóica de Portugal; Dias, R., Araújo, A., Terrinha, P., Kullberg, J.C., Eds.; Escolar: Lisbon, Portugal, 2013; Volume II, pp. 195–347. ISBN 978-972-592-364-1. [Google Scholar]

- Zbyszewski, G. Notícia Explicativa da Folha 22-B—Vieira de Leiria. In Carta Geológica de Portugal na Escala de 1/50 000; Laboratório Nacional de Energia e Geologia: Amadora, Portugal, 1965; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Kullberg, J.C.R. Evolução Tectónica Mesozóica da Bacia Lusitaniana; Universidade Nova de Lisboa: Lisboa, Portugal, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kullberg, J.; Rocha, R.; Rey, J. A Bacia Lusitaniana: Estratigrafia, Paleogeografia e Tectónica. In Geologia de Portugal no Contexto da Ibéria; Dias, R., Araújo, A., Terrinha, P., Kullberg, J.C., Eds.; Universidade de Évora: Évora, Portugal, 2006; pp. 317–368. [Google Scholar]

- Calvín, P.; Oliva-Urcia, B.; Kullberg, J.C.; Torres-López, S.; Casas-Sainz, A.; Villalaín, J.J.; Soto, R. Applying Magnetic Techniques to Determine the Evolution of Reactive Diapirs: A Case Study of the Lusitanian Basin. Tectonophysics 2023, 868, 230088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casacão, J.; Silva, F.; Rocha, J.; Almeida, J.; Santos, M. Aspects of Salt Diapirism and Structural Evolution of Mesozoic-Cenozoic Basins at the West Iberian Margin. Am. Assoc. Pet. Geol. Bull. 2023, 107, 49–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davison, I.; Barreto, P. Deformation and Sedimentation Processes, and Hydrocarbon Accumulations on Upturned Salt Diapir Flanks in the Lusitanian Basin, Portugal. Pet. Geosci. 2019, 27, petgeo2019-138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kottek, M.; Grieser, J.; Beck, C.; Rudolf, B.; Rubel, F. World Map of the Köppen-Geiger Climate Classification Updated. Meteorol. Z. 2006, 15, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La Pasta Cordeiro, M.; Nunes, J.P.; Condesso de Melo, M.T. Impact of Wildfires on Spatial and Temporal Evolution of Groundwater Recharge in an Atlantic Pine Forest: An Integrated Approach Using Field, Remote Sensing and Modeling. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2025, 59, 102408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkhurst, D.L.; Appelo, C.A.J. User’s Guide to PHREEQC (Version 2): A Computer Program for Speciation, Batch-Reaction, One-Dimensional Transport, and Inverse Geochemical Calculations; Water-Resources Investigations Report 99-4259; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helsel, D.R.; Hirsch, R.M. Statistical Methods in Water Resources; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, C.E.; Crawford, J. A New Precipitation Weighted Method for Determining the Meteoric Water Line for Hydrological Applications Demonstrated Using Australian and Global GNIP Data. J. Hydrol. 2012, 464–465, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, J.; Hughes, C.E.; Lykoudis, S. Alternative Least Squares Methods for Determining the Meteoric Water Line, Demonstrated Using GNIP Data. J. Hydrol. 2014, 519, 2331–2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hem, J.D. Study and Interpretation of the Chemical Characteristics of Natural Water; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Eklund, T.J.; Mcdowell, W.H.; Pringle, C.M. Seasonal Variation of Tropical Precipitation Chemistry: La Selva, Costa Rica. Atmos. Environ. 1997, 31, 3903–3910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busby, J.; Lewis, M.; Reeves, H.; Lawley, R. Initial Geological Considerations before Installing Ground Source Heat Pump Systems. Q. J. Eng. Geol. Hydrogeol. 2009, 42, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloomfield, J.P.; Jackson, C.R.; Stuart, M.E. Changes in Groundwater Levels, Temperature and Quality in the UK over the 20th Century: An Assessment of Evidence of Impacts from Climate Change. 2013. Available online: https://nora.nerc.ac.uk/id/eprint/503271/ (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Szczucińska, A.M.; Wasielewski, H. Seasonal Water Temperature Variability of Springs from Porous Sediments in Gryżynka Valley, Western Poland. Quaest. Geogr. 2013, 32, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcalá, F.J.; Custodio, E. Using the Cl/Br Ratio as a Tracer to Identify the Origin of Salinity in Aquifers in Spain and Portugal. J. Hydrol. 2008, 359, 189–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condesso de Melo, M.T. Flow and Hydrogeochemical Mass Transport Model of the Aveiro Cretaceous Multilayer Aquifer (Portugal). Ph.D. Thesis, University of Aveiro, Aveiro, Portugal, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang, L.; Song, Y.; Leach, D.; Liu, Y.; Hou, Z.; Fard, M. Vanished Evaporites, Halokinetic Structure, and Zn-Pb Mineralization in the World-Class Angouran Deposit, Northwestern Iran. Bull. Geol. Soc. Am. 2024, 136, 1569–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghipour, S.; Khalili, M.; MacKizadeh, M.A.; Kananian, A.; Taghipour, B. Mineralogy, Geochemistry and Petrogenesis of Igneous Inclusions within Three Inactive Diapirs, Zagros Belt, Shahre-Kord, Iran. Geol. Mag. 2013, 150, 72–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wei, H.Z.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.J.; Jiang, S.Y.; Eastoe, C.J.; Peryt, T.M. Isotope Evidence for Multiple Sources of B and Cl in Middle Miocene (Badenian) Evaporites, Carpathian Mountains. Appl. Geochem. 2021, 124, 104819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasechko, S. Global Isotope Hydrogeology―Review. Rev. Geophys. 2019, 57, 835–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araguás-Araguás, L.; Froehlich, K.; Rozanski, K. Deuterium and Oxygen-18 Isotope Composition of Precipitation and Atmospheric Moisture. Hydrol. Process 2000, 14, 1341–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchina, C.; Zuecco, G.; Chiogna, G.; Bianchini, G.; Carturan, L.; Comiti, F.; Engel, M.; Natali, C.; Borga, M.; Penna, D. Alternative Methods to Determine the Δ2H-Δ18O Relationship: An Application to Different Water Types. J. Hydrol. 2020, 587, 124951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putman, A.L.; Fiorella, R.P.; Bowen, G.J.; Cai, Z. A Global Perspective on Local Meteoric Water Lines: Meta-Analytic Insight Into Fundamental Controls and Practical Constraints. Water Resour. Res. 2019, 55, 6896–6910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, W.V. Reduced Major Axis Regression. In Wiley StatsRef: Statistics Reference Online; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, H. Isotopic Variations in Meteoric Waters. Science 1961, 177, 1702–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dansgaard, W. Stable Isotopes in Precipitation. Tellus 1964, 16, 436–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreira, P.M.M.; Araujo, M.F.; Nunes, D. Isotopic Composition of Precipitation in the Mediterranean Basin in Relation to Air Circulation and Climate; IAEA: Vienna, Austria, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, I.D.; Fritz, P. Environmental Isotopes in Hydrogeology; Lewis Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 1997; ISBN 1566702496. [Google Scholar]

- Bershaw, J. Controls on Deuterium Excess across Asia. Geosciences 2018, 8, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Precipitation (mm/Month) | Na+/Ca2+ | K+/Na+ | Mg2+/Na+ | Mg2+/Ca2+ | Na+/Cl− | HCO3−/Cl− | SO42−/Cl− | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seawater | 104.7 | 44.65 | 0.02 | 0.12 | 5.43 | 0.85 | 0.0043 | 0.05 | |

| R1 | October-2022 | 117.9 | 0.94 | 0.15 | 0.20 | 0.19 | 0.88 | 1.66 | 0.09 |

| R2 | November-2022 | 200.5 | 4.47 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.35 | 1.64 | 0.76 | 0.09 |

| R3 | December-2022 | 124.3 | 1.91 | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.17 | 3.07 | 7.45 | 0.20 |

| R4 | January-2023 | 10.8 | 5.73 | 0.03 | 0.11 | 0.61 | 0.91 | 0.07 | 0.05 |

| R5 | February-2023 | 45.2 | 1.52 | 0.05 | 0.19 | 0.29 | 1.02 | 0.70 | 0.09 |

| R7 | March-2023 | 15.3 | 2.46 | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.33 | 1.00 | 0.36 | 0.06 |

| R7 | April-2023 | 28 | 2.82 | 0.07 | 0.13 | 0.36 | 0.96 | 0.29 | 0.07 |

| R8 | May-2023 | 19.7 | 1.41 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.26 | 0.86 | 1.21 | 0.08 |

| R9 | June-2023 | 0.62 | 0.29 | 0.27 | 0.16 | 1.06 | 4.14 | 0.08 |

| Major Ions (mmol/L) | Seawater Composition | R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | ||||||||||

| October-2022 | November-2022 | December-2022 | January-2023 | ||||||||||||

| Rainwater Composition | Seawater Contribution | Other Sources | Rainwater Composition | Seawater Contribution | Other Sources | Rainwater Composition | Seawater Contribution | Other Sources | Rainwater Composition | Seawater Contribution | Other Sources | ||||

| Na+ | 456.8 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.01 | 0.36 | 0.22 | 0.14 | 0.34 | 0.09 | 0.24 | 1.00 | 1.01 | −0.01 | ||

| K+ | 10 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.01 | ||

| Ca2+ | 10.2 | 0.17 | 0.00 | 0.16 | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.18 | 0.00 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.02 | 0.15 | ||

| Mg2+ | 55.5 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.11 | 0.12 | −0.02 | ||

| Cl− | 536 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.00 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.00 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.00 | 1.18 | 1.18 | 0.00 | ||

| SO42− | 28.1 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.00 | ||

| fsw | 0.0003 | 0.0005 | 0.0002 | 0.0022 | |||||||||||

| Major Ions (mmol/L) | R5 | R6 | R7 | R8 | R9 | ||||||||||

| February-2023 | March-2023 | April-2023 | May-2023 | June-2023 | |||||||||||

| Rainwater Composition | Seawater Contribution | Other Sources | Rainwater Composition | Seawater Contribution | Other Sources | Rainwater Composition | Seawater Contribution | Other Sources | Rainwater Composition | Seawater Contribution | Other Sources | Rainwater Composition | Seawater Contribution | Other Sources | |

| Na+ | 0.24 | 0.20 | 0.04 | 0.37 | 0.31 | 0.06 | 0.35 | 0.31 | 0.04 | 0.19 | 0.18 | 0.00 | 0.17 | 0.13 | 0.04 |

| K+ | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.05 |

| Ca2+ | 0.16 | 0.00 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.01 | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.01 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.00 | 0.13 | 0.27 | 0.00 | 0.27 |

| Mg2+ | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| Cl− | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.00 | 0.37 | 0.37 | 0.00 | 0.37 | 0.37 | 0.00 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.00 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.00 |

| SO42− | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| fsw | 0.0004 | 0.0007 | 0.0007 | 0.0004 | 0.0003 | ||||||||||

| Samples | Physical Chemical Parameters | Major Ions (mg L−1) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | T (°C) | EC (mS/cm) | Eh (mV) | DO (mg/L) | Na+ | Mg2+ | K+ | Ca2+ | HCO3− | Cl− | SO42− | ||

| Springs (n = 7 and n = 60) | MIN | 5.74 | 14.69 | 133 | 214 | 0.60 | 0.60 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.02 | 0.69 | 0.07 |

| MAX | 7.18 | 19.57 | 283 | 438 | 5.54 | 0.88 | 0.18 | 0.05 | 0.82 | 1.44 | 1.02 | 0.21 | |

| AVG | 6.49 | 17.21 | 193 | 331 | 3.20 | 0.73 | 0.13 | 0.05 | 0.33 | 0.49 | 0.88 | 0.12 | |

| SD | 0.71 | 1.29 | 57 | 108 | 2.34 | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.28 | 0.58 | 0.14 | 0.07 | |

| MED | 6.66 | 17.16 | 183 | 370 | 3.60 | 0.74 | 0.14 | 0.05 | 0.24 | 0.42 | 0.94 | 0.07 | |

| Range | 1.44 | 4.88 | 150 | 224 | 4.94 | 0.28 | 0.11 | 0.01 | 0.71 | 1.42 | 0.32 | 0.15 | |

| Confined Aquifer (n = 29) | MIN | 5.09 | 15.41 | 122 | 290 | 0.00 | 0.78 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.50 | 0.07 |

| MAX | 8.35 | 23.36 | 2250 | 362 | 10.42 | 11.00 | 3.85 | 0.29 | 6.69 | 4.55 | 17.63 | 2.71 | |

| AVG | 6.30 | 18.37 | 543 | 317 | 4.38 | 2.56 | 0.83 | 0.11 | 1.45 | 1.28 | 2.77 | 0.57 | |

| SD | 0.71 | 1.67 | 532 | 18 | 3.28 | 2.74 | 0.86 | 0.05 | 1.65 | 1.02 | 4.08 | 0.61 | |

| MED | 6.21 | 18.06 | 318 | 313 | 4.45 | 1.37 | 0.46 | 0.10 | 0.84 | 1.07 | 1.05 | 0.33 | |

| Range | 3.26 | 7.95 | 2128 | 71 | 10.42 | 10.23 | 3.77 | 0.24 | 6.61 | 4.47 | 17.13 | 2.64 | |

| Unconfined Aquifer (n = 22 and n = 239) | MIN | 5.85 | 9.33 | 124 | 144 | 0.16 | 0.34 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.15 | 0.22 | 0.32 | 0.01 |

| MAX | 8.02 | 20.42 | 1756 | 458 | 6.83 | 7.66 | 1.38 | 0.59 | 3.64 | 7.85 | 6.69 | 0.59 | |

| AVG | 7.44 | 16.22 | 480 | 341 | 4.61 | 1.50 | 0.29 | 0.13 | 1.21 | 2.27 | 1.53 | 0.15 | |

| SD | 0.50 | 2.35 | 362 | 94 | 1.96 | 1.65 | 0.30 | 0.13 | 0.90 | 1.96 | 1.56 | 0.13 | |

| MED | 7.57 | 16.50 | 363 | 380 | 4.93 | 0.75 | 0.19 | 0.10 | 1.01 | 1.69 | 0.80 | 0.11 | |

| Range | 2.17 | 11.09 | 1632 | 313 | 6.67 | 7.32 | 1.29 | 0.57 | 3.49 | 7.63 | 6.37 | 0.57 | |

| Surface Water (n = 2) | MIN | 7.47 | 16.12 | 410 | 263 | 9.48 | 1.54 | 0.22 | 0.08 | 0.89 | 1.01 | 1.63 | 0.49 |

| MAX | 8.09 | 16.31 | 883 | 331 | 10.42 | 3.73 | 0.64 | 0.20 | 1.67 | 2.87 | 3.95 | 0.52 | |

| OLS | RMA | PWLS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Samples | Without Outliers | All Samples | Without Outliers | All Samples | Without Outliers | |

| a | 5.32 | 7.60 | 5.70 | 8.06 | 8.12 | 8.45 |

| b | −4.53 | 4.49 | −3.50 | 6.19 | 7.32 | 8.60 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

La Pasta Cordeiro, M.; Wallström, J.; Condesso de Melo, M.T. Tracing the Origin of Groundwater Salinization in Multilayered Coastal Aquifers Using Geochemical Tracers. Water 2026, 18, 252. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020252

La Pasta Cordeiro M, Wallström J, Condesso de Melo MT. Tracing the Origin of Groundwater Salinization in Multilayered Coastal Aquifers Using Geochemical Tracers. Water. 2026; 18(2):252. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020252

Chicago/Turabian StyleLa Pasta Cordeiro, Mariana, Johanna Wallström, and Maria Teresa Condesso de Melo. 2026. "Tracing the Origin of Groundwater Salinization in Multilayered Coastal Aquifers Using Geochemical Tracers" Water 18, no. 2: 252. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020252

APA StyleLa Pasta Cordeiro, M., Wallström, J., & Condesso de Melo, M. T. (2026). Tracing the Origin of Groundwater Salinization in Multilayered Coastal Aquifers Using Geochemical Tracers. Water, 18(2), 252. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020252