Enhancing Osmotic Power Generation and Water Conservation with High-Performance Thin-Film Nanocomposite Membranes for the Mining Industry

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation of Thin-Film Nanocomposite Membrane with Functionalized Carbon Nanotubes (fMWCNTs)

2.3. Preparation of Polydopamine Coating and Polyamide Layer

2.4. The Characterization of the Membranes

2.5. Assessment of Membrane Performance

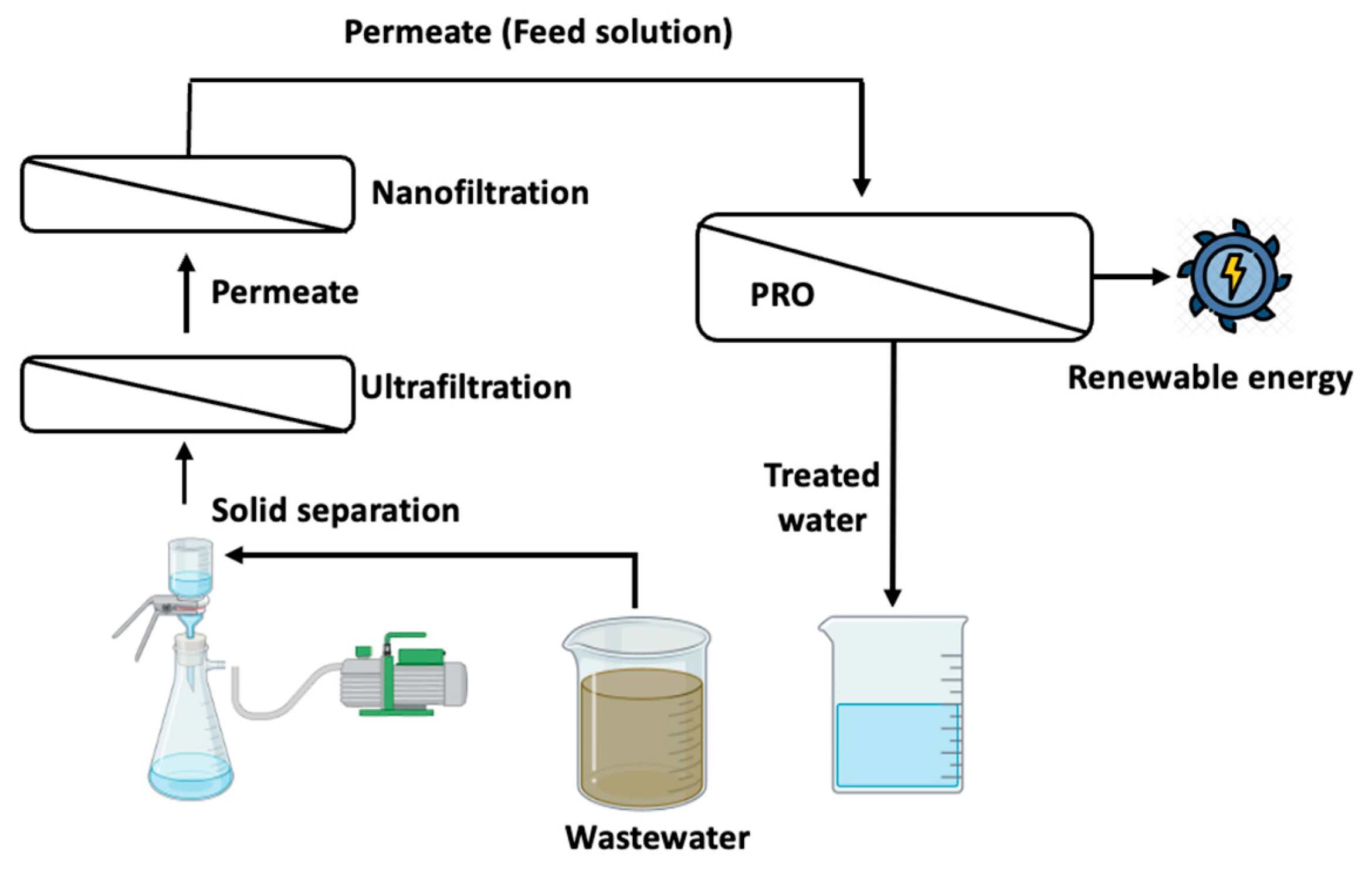

2.6. Pretreatment of Mining Wastewater for the PRO Process

2.7. Evaluation of PRO Performance

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of Fabricated Membranes

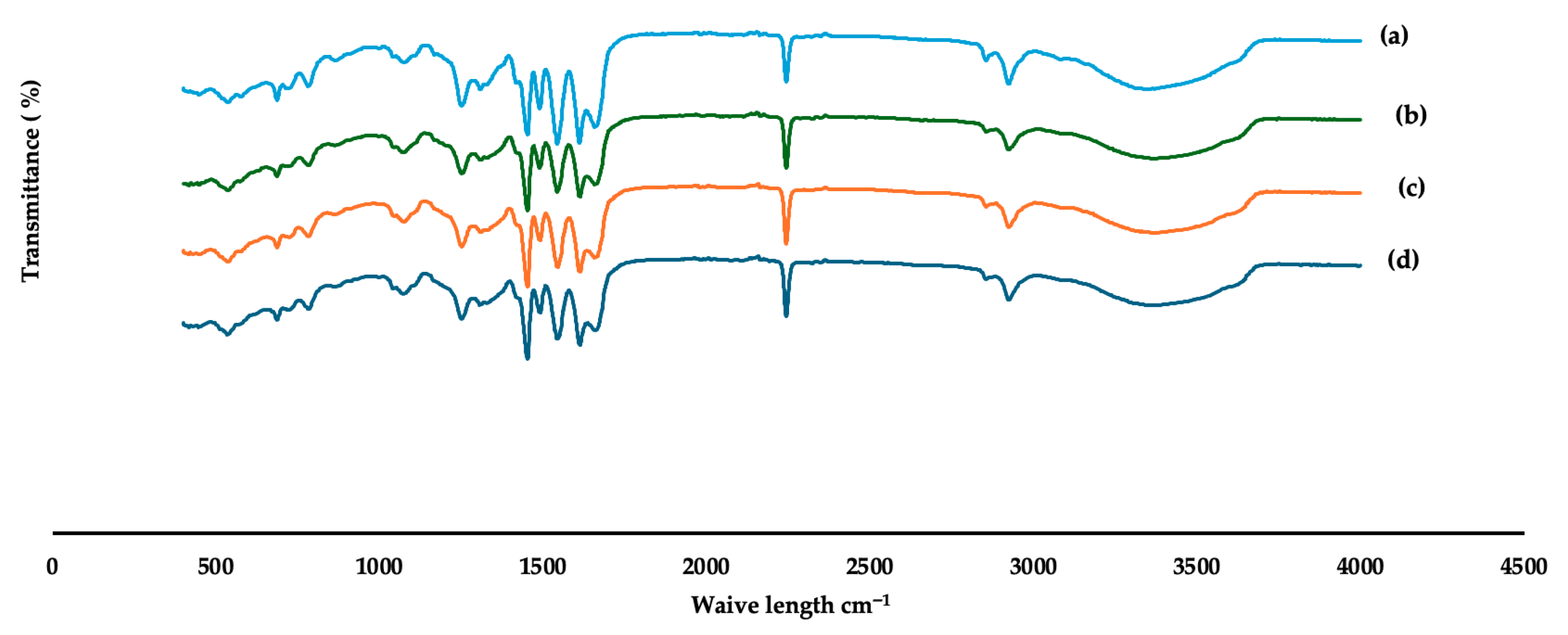

3.1.1. FTIR Analysis of Fabricated Membranes

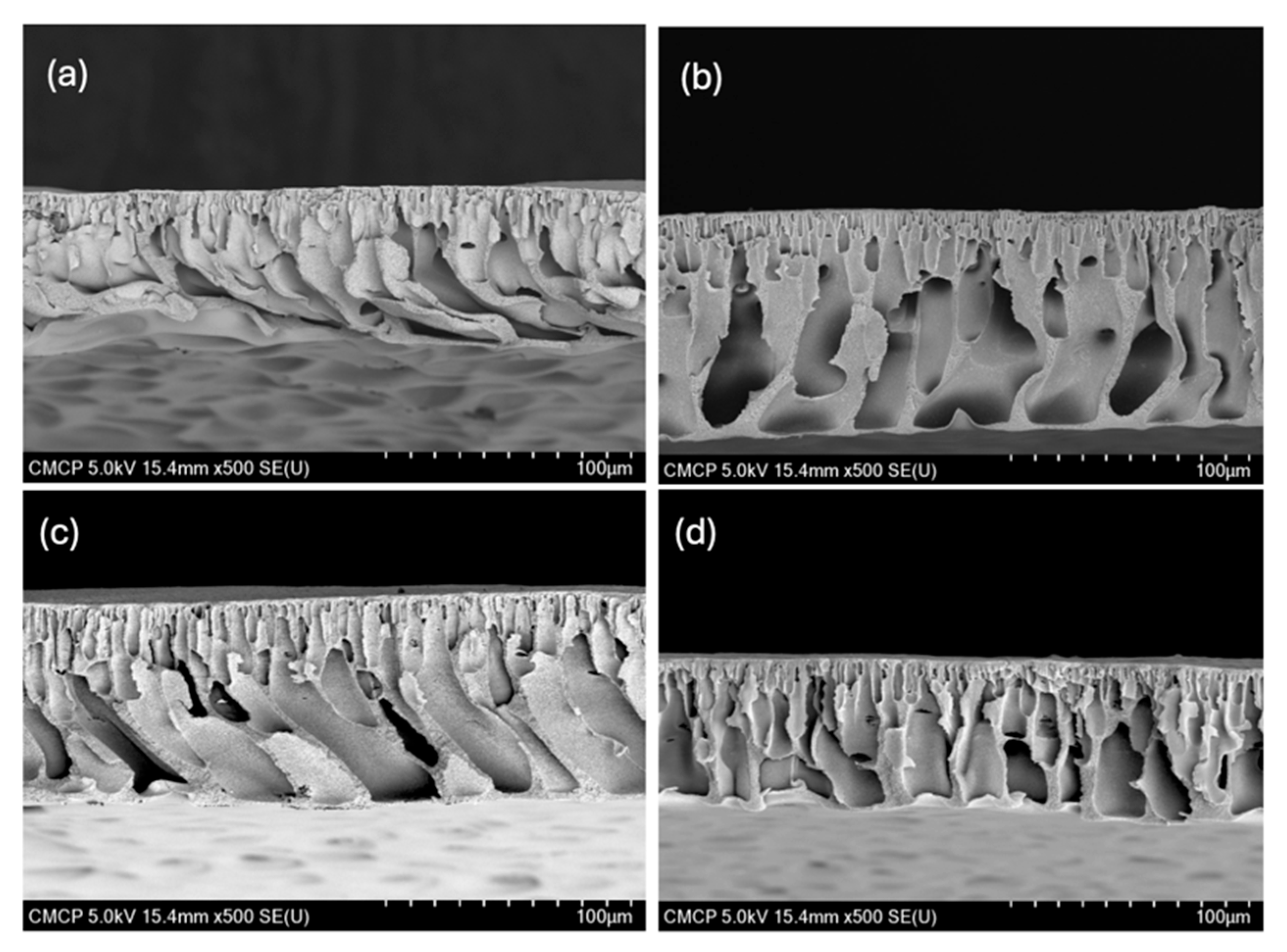

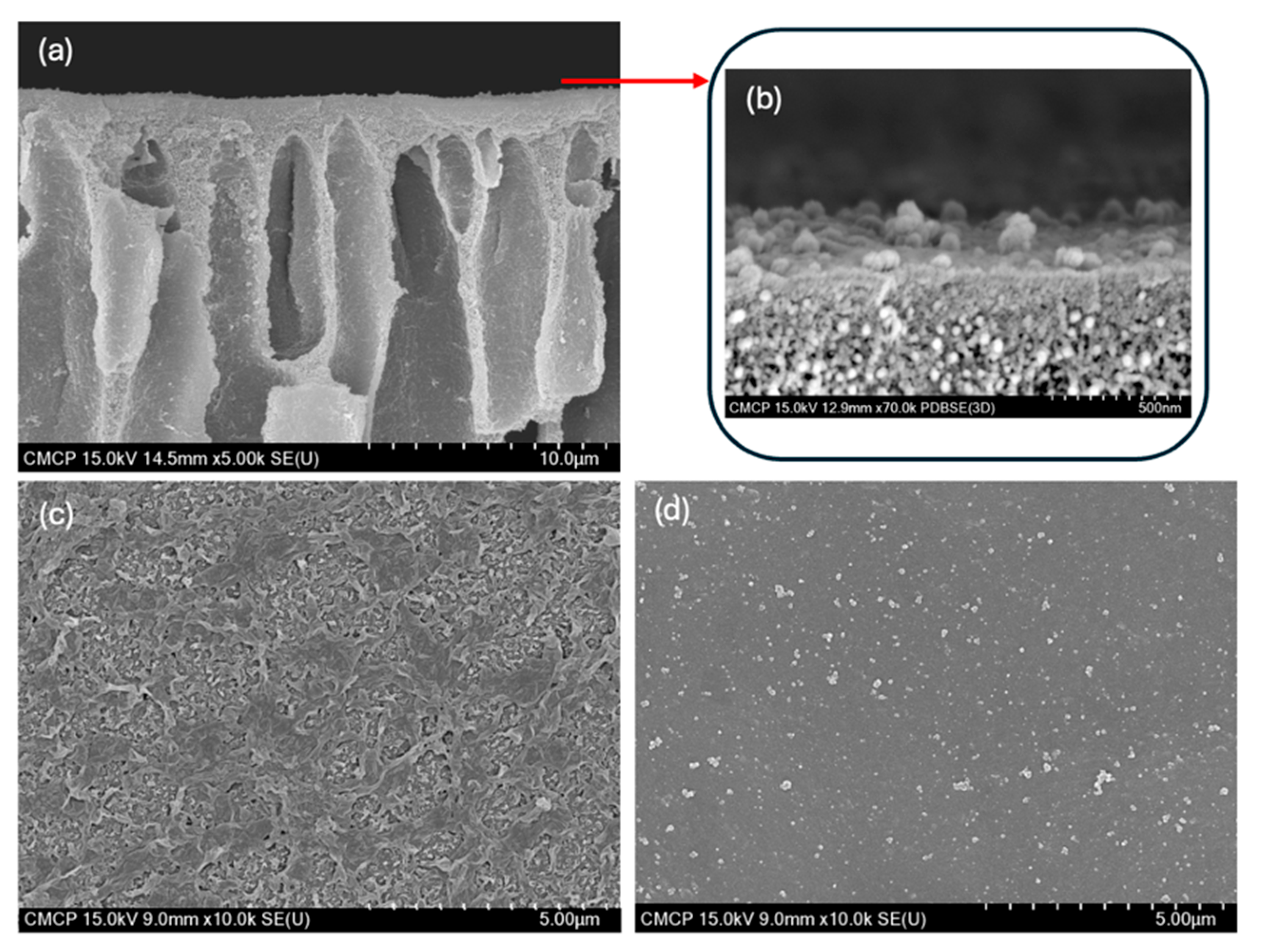

3.1.2. Morphology of Fabricated Membranes

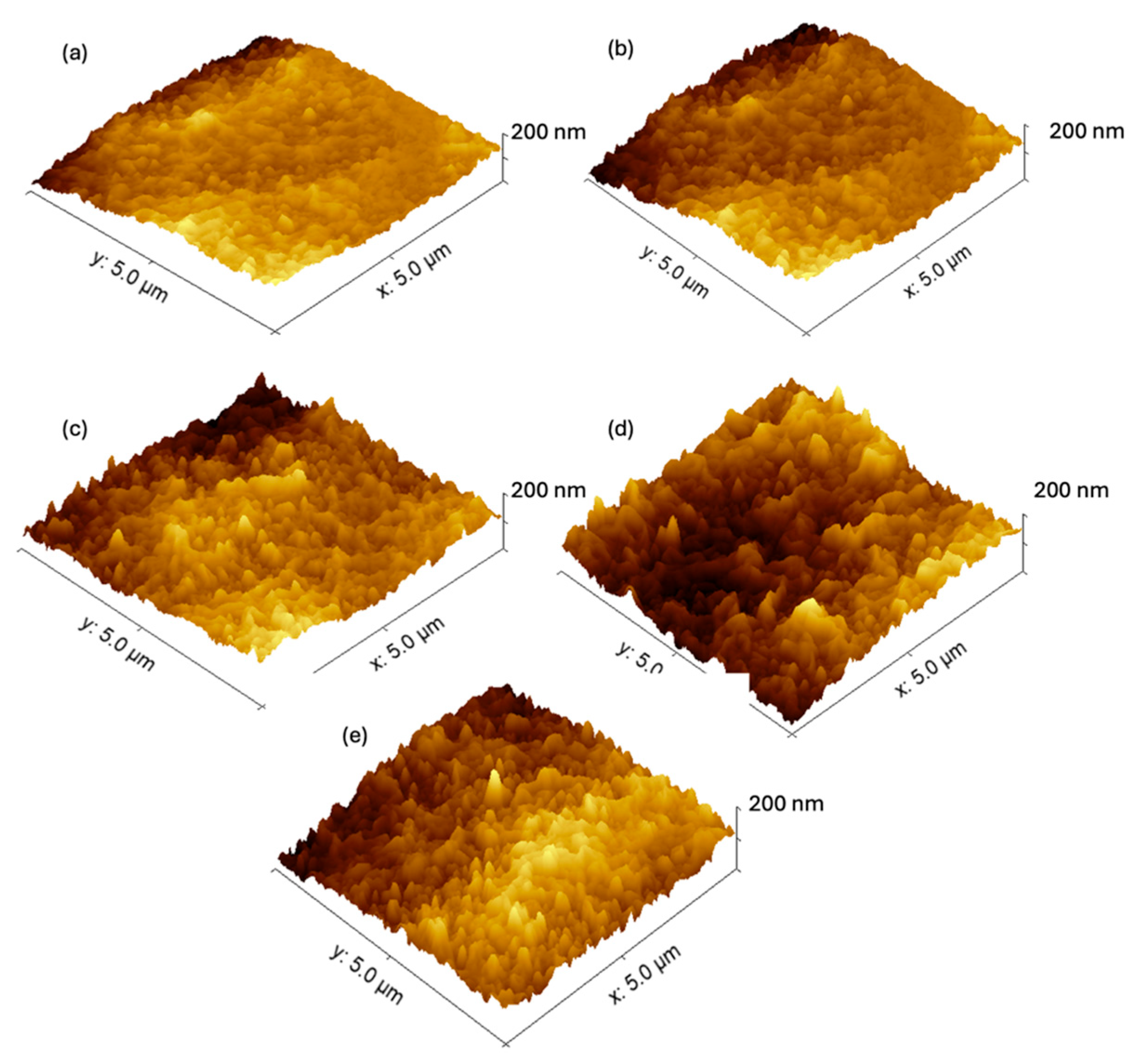

3.1.3. AFM Analysis of the Roughness of the Fabricated Membranes

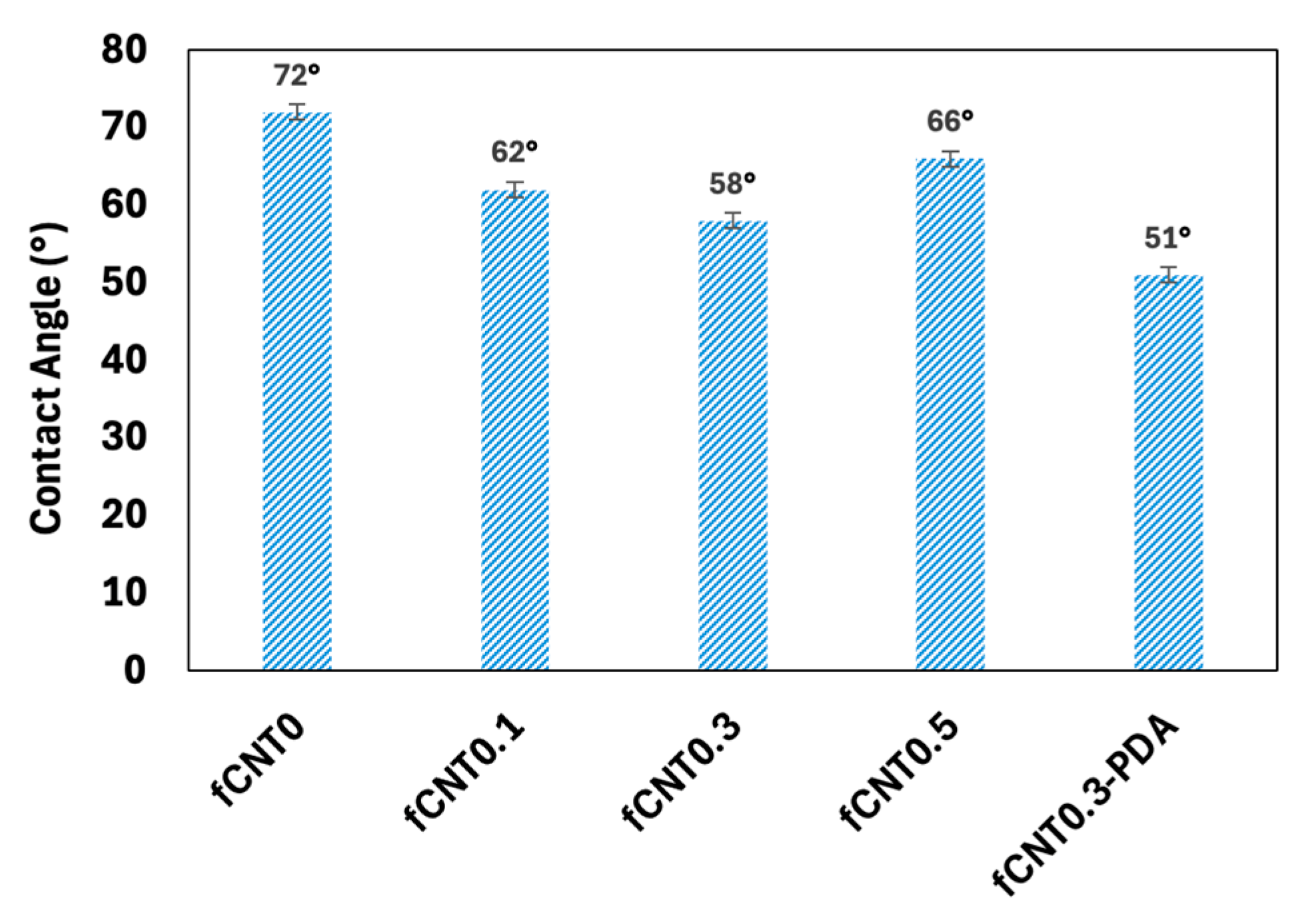

3.1.4. The Hydrophilicity of the Fabricated Membranes

3.1.5. Intrinsic Separation Properties of the Membranes

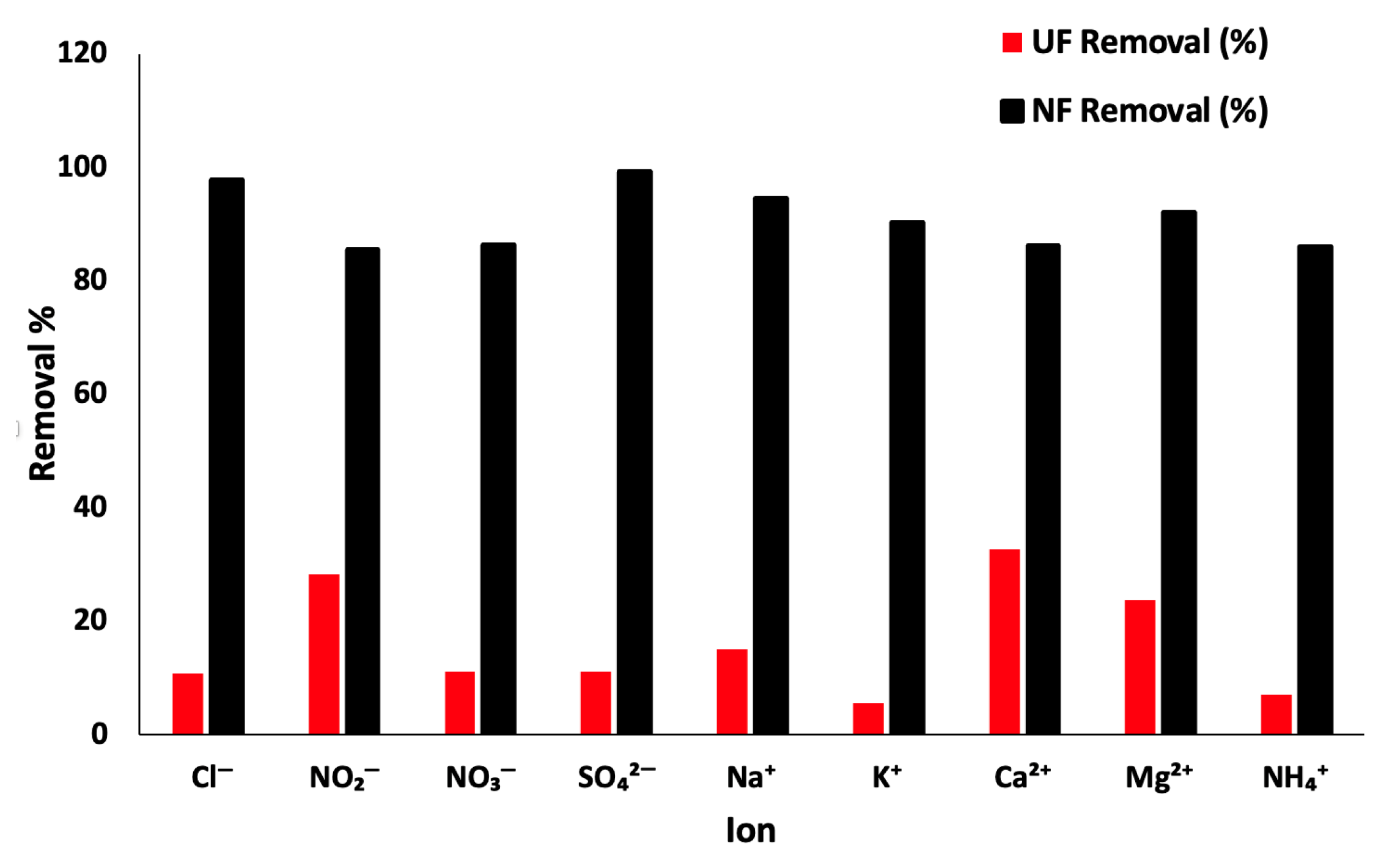

3.2. Pretreatment Tests Results

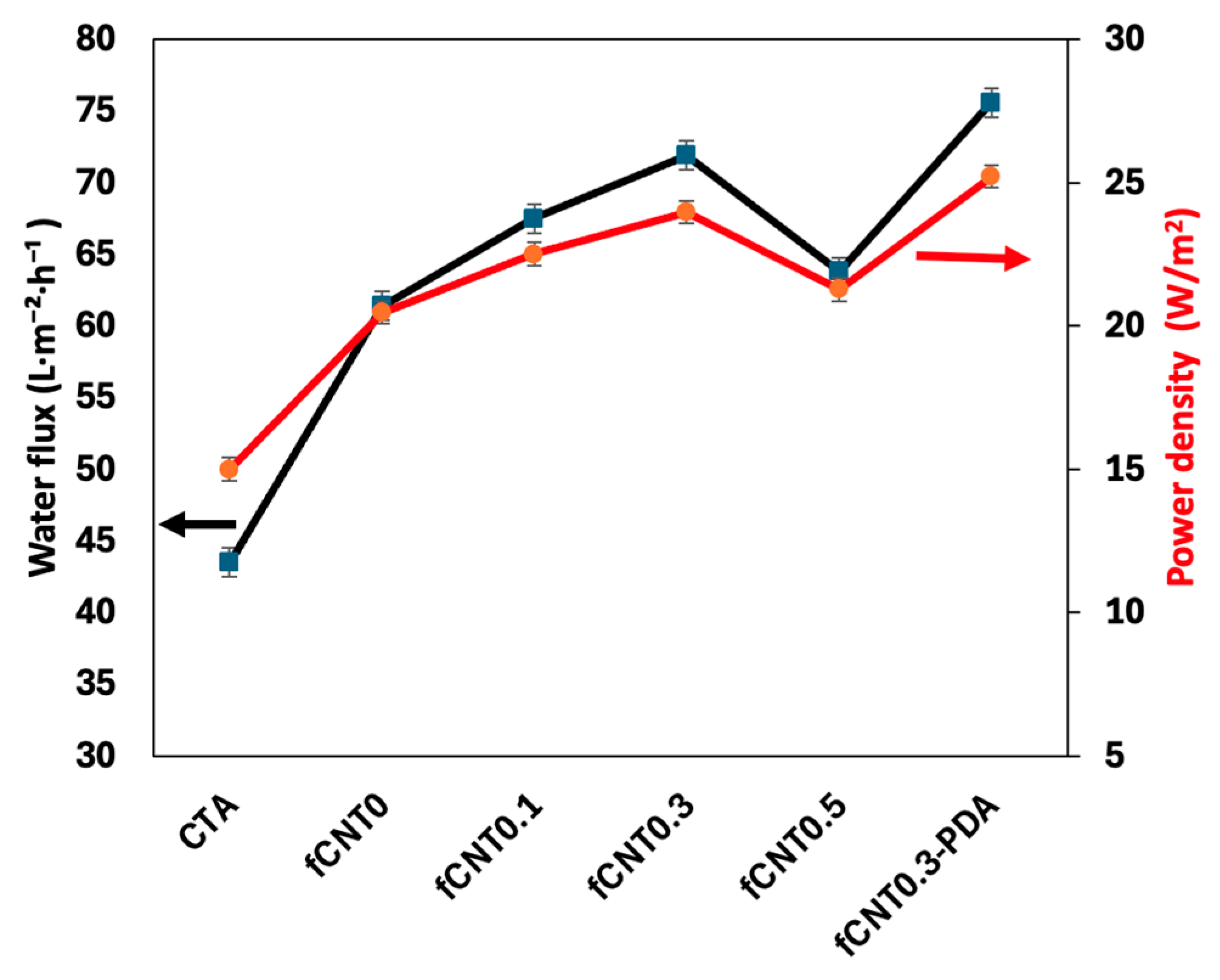

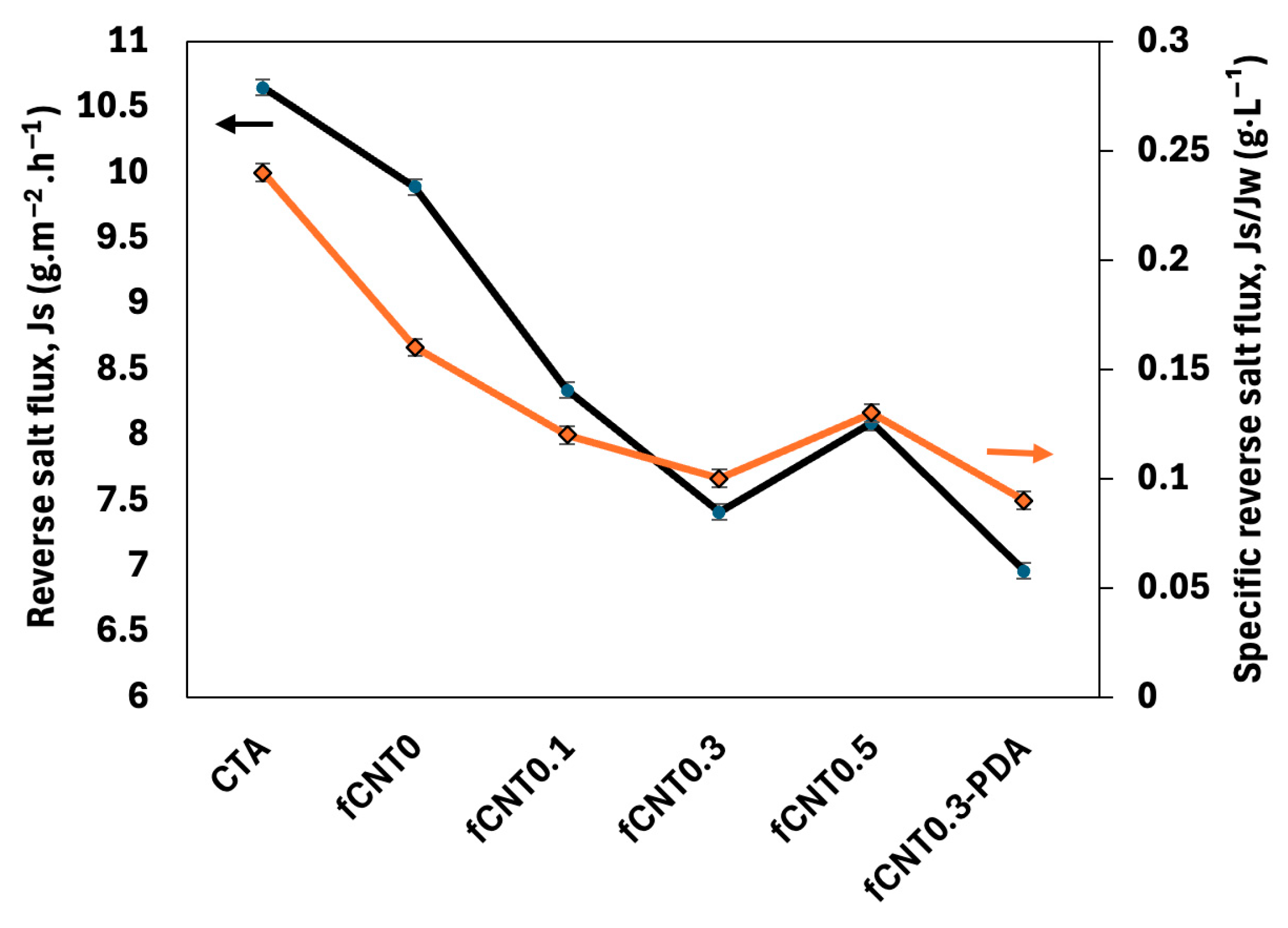

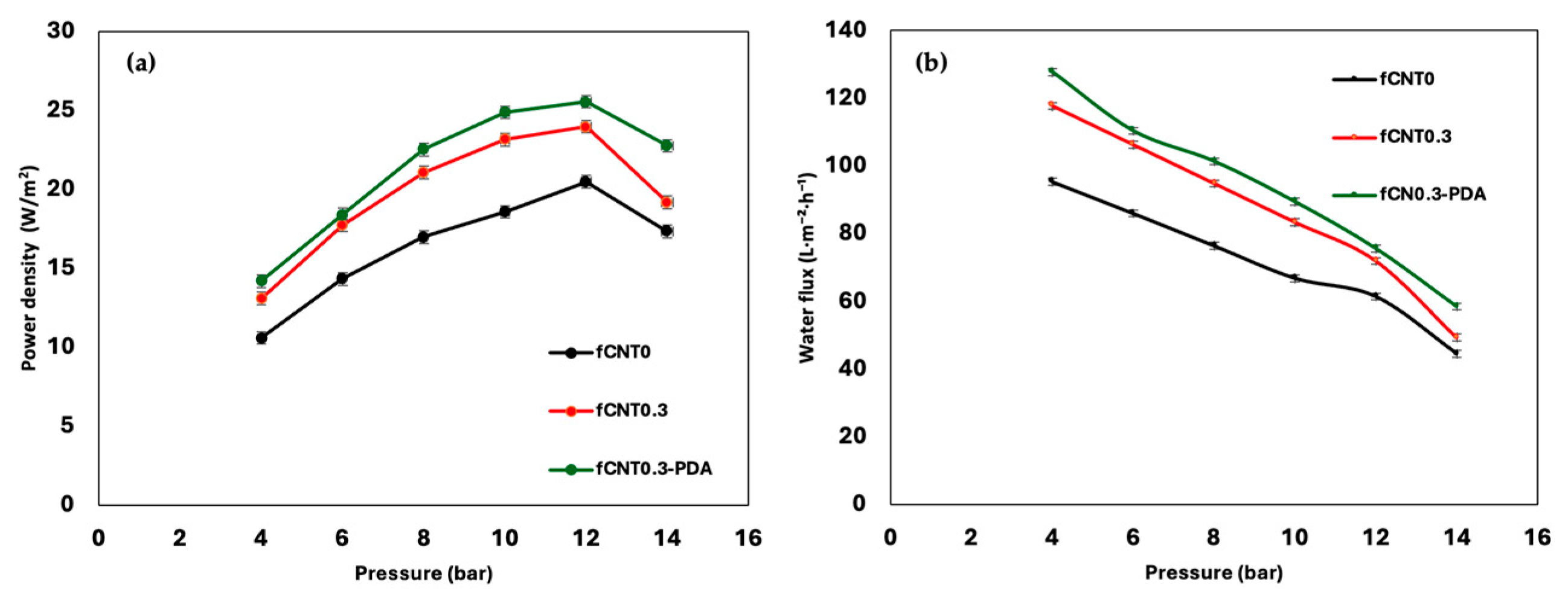

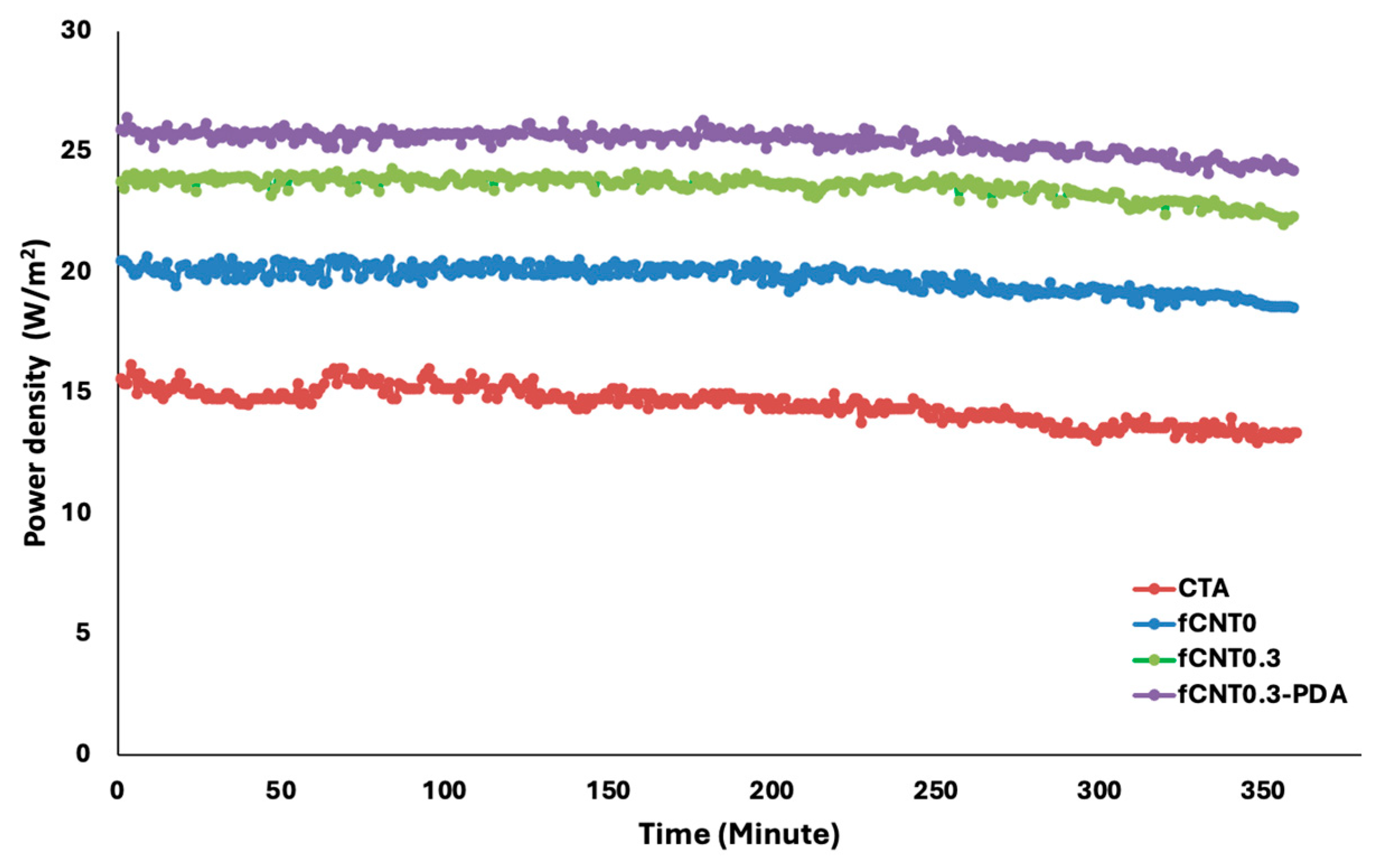

3.3. PRO Test Results

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Su, Z.; Malankowska, M.; Brigsted, J.S.; Popkov, A.; Guo, H.; Pedersen, L.S.; Pinelo, M. Novel Membrane Coating Methods Involving Use of Graphene Oxide and Polyelectrolytes for Development of Sustainable Energy Production: Pressure Retarded Osmosis (PRO) and Enzymatic Membrane Reactor (EMR). Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2024, 204, 418–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Mo, Z.; She, Q. Comparison of Energy Efficiency between Atmospheric Batch Pressure-Retarded Osmosis and Single-Stage Pressure-Retarded Osmosis. Membranes 2023, 13, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liew, Z.-S.; Ho, Y.-C.; Lau, W.J.; Nordin, N.A.H.M.; Lai, S.-O.; Ma, J. Altering Substrate Properties of Thin Film Nanocomposite Membrane by Al2O3 Nanoparticles for Engineered Osmosis Process. Environ. Technol. 2024, 45, 1052–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, E.; Qadir, M.; Van Vliet, M.T.H.; Smakhtin, V.; Kang, S. The State of Desalination and Brine Production: A Global Outlook. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 657, 1343–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelkader, B.A.; Navas, D.R.; Sharqawy, M.H. A Novel Spiral Wound Module Design for Harvesting Salinity Gradient Energy Using Pressure Retarded Osmosis. Renew. Energy 2023, 203, 542–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straub, A.P.; Deshmukh, A.; Elimelech, M. Pressure-Retarded Osmosis for Power Generation from Salinity Gradients: Is It Viable? Energy Environ. Sci. 2016, 9, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chintalacheruvu, S.; Ren, Y.; Maisonneuve, J. Effectively Using Heat to Thermally Enhance Pressure Retarded Osmosis. Desalination 2023, 556, 116570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Zainati, N.; Ibrar, I.; Altaee, A.; Subbiah, S.; Zhou, J. Multiple Staging of Pressure Retarded Osmosis: Impact on the Energy Generation. Desalination 2024, 573, 117199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.Y. Review of Analytical and Numerical Modeling for Pressure Retarded Osmosis Membrane Systems. Desalination 2023, 560, 116655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.; Wang, L.; Wang, Z.; Cooper, N.J.; Elimelech, M. Directing the Research Agenda on Water and Energy Technologies with Process and Economic Analysis. Energy Environ. Sci. 2023, 16, 714–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.-Q.; Hung, W.-S.; Yu, H.-H.; Hu, C.-C.; Lee, K.-R.; Lai, J.-Y.; Xu, Z.-K. Forward Osmosis Membranes with Unprecedented Water Flux. J. Membr. Sci. 2017, 529, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binger, Z.M.; Achilli, A. Forward Osmosis and Pressure Retarded Osmosis Process Modeling for Integration with Seawater Reverse Osmosis Desalination. Desalination 2020, 491, 114583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.J.; Park, K.; Kim, D.Y.; Zhan, M.; Hong, S.; Lee, J.-H. High-Performance and Durable Pressure Retarded Osmosis Membranes Fabricated Using Hydrophilized Polyethylene Separators. J. Membr. Sci. 2021, 619, 118796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarp, S.; Li, Z.; Saththasivam, J. Pressure Retarded Osmosis (PRO): Past Experiences, Current Developments, and Future Prospects. Desalination 2016, 389, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, X.; Wang, X.; Liu, S.; Gao, H.; Xu, C.; Crittenden, J.; Chen, Y. A Freestanding Graphene Oxide Membrane for Efficiently Harvesting Salinity Gradient Power. Carbon 2018, 138, 410–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Yao, Z.; Jiao, L.; Waheed, M.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, L. Separation Mechanism, Selectivity Enhancement Strategies and Advanced Materials for Mono-/Multivalent Ion-Selective Nanofiltration Membrane. Adv. Membr. 2022, 2, 100032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, C.; Zhai, Z.; Jiang, C.; Hu, P.; Zhao, S.; Xue, S.; Yang, Z.; He, T.; Niu, Q.J. Recent Advances in High-Performance TFC Membranes: A Review of the Functional Interlayers. Desalination 2021, 500, 114869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, P.S.; Ismail, A.F. Chemically Functionalized Polyamide Thin Film Composite Membranes: The Art of Chemistry. Desalination 2020, 495, 114655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siahtiri, S.; Sahraei, A.A.; Mokarizadeh, A.H.; Baghani, M.; Bodaghi, M.; Baniassadi, M. Influence of Curing Agents Molecular Structures on Interfacial Characteristics of Graphene/Epoxy Nanocomposites: A Molecular Dynamics Framework. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2023, 308, 2300030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Wang, S.; Xu, H.; Zhou, Y.; Gao, C. Preparation of Polyamide Thin Film Nanocomposite Membranes Containing Silica Nanoparticles via an In-Situ Polymerization of SiCl4 in Organic Solution. J. Membr. Sci. 2018, 565, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, G.; Wang, P.; Zhou, Z.; Hu, Y. New Insights into the Role of an Interlayer for the Fabrication of Highly Selective and Permeable Thin-Film Composite Nanofiltration Membrane. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 7349–7356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambi Krishnan, J.; Venkatachalam, K.R.; Ghosh, O.; Jhaveri, K.; Palakodeti, A.; Nair, N. Review of Thin Film Nanocomposite Membranes and Their Applications in Desalination. Front. Chem. 2022, 10, 781372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shadravan, A.; Goh, P.S.; Ismail, A.F.; Amani, M. Fouling in thin film nanocomposite membranes for power generation through pressure retarded osmosis. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2112.02503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, H.; Garg, M.C. Fabrication of Polymeric Nanocomposite Forward Osmosis Membranes for Water Desalination—A Review. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2021, 23, 101561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samieirad, S.; Mousavi, S.M.; Saljoughi, E. Alignment of Functionalized Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes in Forward Osmosis Membrane Support Layer Induced by Electric and Magnetic Fields. Powder Technol. 2020, 364, 538–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M.; Wang, R.; Goh, K.; Liao, Y.; Fane, A.G. Synthesis and Characterization of High-Performance Novel Thin Film Nanocomposite PRO Membranes with Tiered Nanofiber Support Reinforced by Functionalized Carbon Nanotubes. J. Membr. Sci. 2015, 486, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Son, M.; Choi, H. Integrating Seawater Desalination and Wastewater Reclamation Forward Osmosis Process Using Thin-Film Composite Mixed Matrix Membrane with Functionalized Carbon Nanotube Blended Polyethersulfone Support Layer. Chemosphere 2017, 185, 1181–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Malankowska, M.; Marschall Thostrup, T.; DeMartini, M.; Khajavi, P.; Guo, H.; Storm Pedersen, L.; Pinelo, M. Comparison of 2D and 3D Materials on Membrane Modification for Improved Pressure Retarded Osmosis (PRO) Process. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2024, 285, 119638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, W.N.A.S.; Mohd Nawi, N.S.; Lau, W.J.; Ho, Y.C.; Aziz, F.; Ismail, A.F. Enhancing Physiochemical Substrate Properties of Thin-Film Composite Membranes for Water and Wastewater Treatment via Engineered Osmosis Process. Polymers 2023, 15, 1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zheng, L.; Feng, Q.; Xie, X.; Yong, Z.; He, J.; Yang, L.; Zhao, X. In Situ Surface Modification of Forward Osmosis Membrane by Polydopamine/Polyethyleneimine-Silver Nanoparticle for Anti-Fouling Improvement in Municipal Wastewater Treatment. Water Sci. Technol. 2023, 87, 2195–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlZainati, N.; Saleem, H.; Altaee, A.; Zaidi, S.J.; Mohsen, M.; Hawari, A.; Millar, G.J. Pressure Retarded Osmosis: Advancement, Challenges and Potential. J. Water Process Eng. 2021, 40, 101950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samavati, Z.; Samavati, A.; Goh, P.S.; Fauzi Ismail, A.; Sohaimi Abdullah, M. A Comprehensive Review of Recent Advances in Nanofiltration Membranes for Heavy Metal Removal from Wastewater. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2023, 189, 530–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, C.D.; Rantissi, T.; Gitis, V.; Hankins, N.P. Retention of Natural Organic Matter by Ultrafiltration and the Mitigation of Membrane Fouling through Pre-Treatment, Membrane Enhancement, and Cleaning—A Review. J. Water Process Eng. 2021, 44, 102374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koli, M.M.; Singh, S.P. Surface-Modified Ultrafiltration and Nanofiltration Membranes for the Selective Removal of Heavy Metals and Inorganic Groundwater Contaminants: A Review. Environ. Sci. Water Res. Technol. 2023, 9, 2803–2829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Wan, C.F.; Xiong, J.Y.; Chung, T.-S. Pre-Treatment of Wastewater Retentate to Mitigate Fouling on the Pressure Retarded Osmosis (PRO) Process. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2019, 215, 390–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.F.; Chung, T.-S. Osmotic Power Generation by Pressure Retarded Osmosis Using Seawater Brine as the Draw Solution and Wastewater Retentate as the Feed. J. Membr. Sci. 2015, 479, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, A.E.; Touati, K.; Mulligan, C.N.; McCutcheon, J.R.; Rahaman, M.S. Closed-Loop Pressure Retarded Osmosis Draw Solutions and Their Regeneration Processes: A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 159, 112191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouri, G.; Mulligan, C.N.; Nasiri, F.; Neculita, C.M. Application of Pressure Retarded Osmosis Technology for Sustainable Mining Wastewater Treatment and Energy Generation. In Canadian Society of Civil Engineering Annual Conference; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 75–87. [Google Scholar]

- Son, M.; Park, H.; Liu, L.; Choi, H.; Kim, J.H.; Choi, H. Thin-Film Nanocomposite Membrane with CNT Positioning in Support Layer for Energy Harvesting from Saline Water. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 284, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, M.; Choi, H.; Liu, L.; Celik, E.; Park, H.; Choi, H. Efficacy of Carbon Nanotube Positioning in the Polyethersulfone Support Layer on the Performance of Thin-Film Composite Membrane for Desalination. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 266, 376–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paşaoğlu, M.E.; Koyuncu, İ. Fabrication, Characterization and Application of Flat Sheet PAN/CNC Nanocomposite Nanofiber Pressure-Retarded Osmosis (PRO) Membrane. Desalination Water Treat. 2021, 211, 369–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idris, S.N.A.; Jullok, N.; Lau, W.J.; Ma’Radzi, A.H.; Ong, H.L.; Ramli, M.M.; Dong, C.-D. Modification of Thin Film Composite Pressure Retarded Osmosis Membrane by Polyethylene Glycol with Different Molecular Weights. Membranes 2022, 12, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales, R.R.; Abdel-Wahab, A.; Adham, S.; Han, D.S.; Phuntsho, S.; Suwaileh, W.; Hilal, N.; Shon, H.K. Salinity Gradient Energy Generation by Pressure Retarded Osmosis: A Review. Desalination 2021, 500, 114841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini, M.; Jahanshahi, M.; Rahimpour, A. Synthesis of Novel Thin Film Nanocomposite (TFN) Forward Osmosis Membranes Using Functionalized Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes. J. Membr. Sci. 2013, 435, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, P.; Modi, A.; Bellare, J. Enhanced Flux and Antifouling Property on Municipal Wastewater of Polyethersulfone Hollow Fiber Membranes by Embedding Carboxylated Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes and a Vitamin E Derivative. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2020, 235, 116199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iranpoury, A.; Mehrnia, M.R.; Jafari, S.H.; Najmi, M. Improvement of Fouling Resistance and Mechanical Reinforcement of Polyacrylonitrile Membranes by Amino-functionalized Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes for Membrane Bioreactors Applications. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2022, 139, e52733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.W.; McCloskey, B.D.; Choi, T.H.; Lee, C.; Kim, M.-J.; Freeman, B.D.; Park, H.B. Oxygen Concentration Control of Dopamine-Induced High Uniformity Surface Coating Chemistry. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2013, 5, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Son, M.; Yoon, S.; Celik, E.; Kang, S.; Park, H.; Park, C.H.; Choi, H. Alginate Fouling Reduction of Functionalized Carbon Nanotube Blended Cellulose Acetate Membrane in Forward Osmosis. Chemosphere 2015, 136, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, M.; Novotny, V.; Choi, H. Thin-Film Nanocomposite Membrane with Vertically Embedded Carbon Nanotube for Forward Osmosis. Desalination Water Treat. 2016, 57, 26670–26679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubiak, K.J.; Wilson, M.C.T.; Mathia, T.G.; Carval, P. Wettability versus Roughness of Engineering Surfaces. Wear 2011, 271, 523–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idris, S.N.A.; Jullok, N.; Lau, W.J.; Ong, H.L.; Dong, C.-D. Graphene Oxide Incorporated Polysulfone Substrate for Flat Sheet Thin Film Nanocomposite Pressure Retarded Osmosis Membrane. Membranes 2020, 10, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pakdaman, S.; Nouri, G.; Mulligan, C.N.; Nasiri, F. Integration of Membrane-Based Pretreatment Methods with Pressure-Retarded Osmosis for Performance Enhancement: A Review. Materials 2025, 18, 1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aghapour Aktij, S.; Dadashi Firouzjaei, M.; Haddadi, S.A.; Karami, P.; Taghipour, A.; Yassari, M.; Asad, A.A.; Pilevar, M.; Jafarian, H.; Arjmand, M.; et al. Metal-Organic Frameworks’ Latent Potential as High-Efficiency Osmotic Power Generators in Thin-Film Nanocomposite Membranes. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 481, 148384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yu, W.; Cao, H. Arginine-Functionalized Thin Film Composite Forward Osmosis Membrane Integrating Antifouling and Antibacterial Effects. Membranes 2023, 13, 760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karami, P.; Haque Mizan, M.M.; Khorshidi, B.; Aghapour Aktij, S.; Rahimpour, A.; Soares, J.B.P.; Sadrzadeh, M. Novel Forward Osmosis Membranes Engineered with Polydopamine/Graphene Oxide Interlayers: Synergistic Impact of Monomer Reactivity and Hydrophilic Interlayers. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2023, 62, 11965–11976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Samples | PAN (wt%) | DMF (wt%) | fMWCNTs (wt%) | PDA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| fCNT0 | 16 | 84 | - | - |

| fCNT0.1 | 16 | 84 | 0.1 | - |

| fCNT0.3 | 16 | 84 | 0.3 | - |

| fCNT0.5 | 16 | 84 | 0.5 | - |

| fCNT0.3-PDA | 16 | 84 | 0.3 | + |

| Sample | Sq (nm) | Sa (nm) |

|---|---|---|

| fCNT0 | 25.75 | 18.36 |

| fCNT0.1 | 29.61 | 22.43 |

| fCNT0.3 | 31.54 | 24.60 |

| fCNT0.5 | 35.65 | 29.16 |

| fCNT0.3-PDA | 33.52 | 27.48 |

| Sample | Water Permeability (A, L·m−2·h−1·bar−1) | Salt Permeability (B, L·m−2·h−1) | B/A (bar) | Salt Rejection (%) | Structural Parameter (S, µm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fCNT0 | 4.18 ± 0.08 | 1.98 ± 0.04 | 0.47 | 95.46 | 556 |

| fCNT0.1 | 4.48 ± 0.06 | 1.28 ± 0.02 | 0.28 | 97.21 | 529 |

| fCNT0.3 | 5.29 ± 0.08 | 0.83 ± 0.05 | 0.16 | 98.45 | 511 |

| fCNT0.5 | 4.33 ± 0.09 | 1.51 ± 0.04 | 0.35 | 96.62 | 557 |

| fCNT0.3-PDA | 5.65 ± 0.15 | 0.54 ± 0.03 | 0.1 | 99.05 | 494 |

| CTA | 3.12 ± 0.05 | 2.31 ± 0.05 | 0.74 | 93.1 | 627 |

| Sample | Type of Material | Type of Membrane | FS | DS | Power Density (W/m2) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | PAN + fMWCNTs + PDA | Flat sheet PRO | Gold mining wastewater | 3.0 M (NH4)2CO3 | 25.22 | This study |

| 2 | CTA + PDA + Polyetherimide (PEI) | Flat sheet FO | Raw municipal wastewater | Synthetic seawater | Not applicable (FO study) | [30] |

| 3 | Polyethersulfone + Zwitterionic arginine | Flat sheet FO | Deionized water/model oily wastewater (emulsified oil) | 1.0 M NaCl | Not applicable (FO study) | [54] |

| 4 | PAN + polyphenylsulfone substrate and PDA + graphene oxide (GO) coating | Flat sheet FO/PRO | Aerobically treated palm oil mill effluent | 4.0 M MgCl2 | Not reported | [29] |

| 5 | Polyethersulfone | Hollow fiber PRO | Wastewater retentate | Synthetic seawater brine | 7.3–8.4 | [35] |

| 6 | PDA + polyelectrolytes + GO | Flat sheet PRO | Deionized water | 17.5 wt% NaCl | 2.64 | [1] |

| 7 | Polyphenylsulfone + cellulose acetate phthalate + fMWCNTs | Flat sheet FO | Deionized water | Not applicable | Not applicable (FO study) | [25] |

| 8 | PEI + fMWCNTs | Nanofibrous TFC | Deionized water | 1.0 NaCl | 17.3 | [26] |

| 9 | Triaminopyrimidine monomer + PDA/GO | Commercial flat sheet | Deionized water | 1.0 M NaCl | Not reported | [55] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pakdaman, S.; Mulligan, C.N. Enhancing Osmotic Power Generation and Water Conservation with High-Performance Thin-Film Nanocomposite Membranes for the Mining Industry. Water 2026, 18, 248. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020248

Pakdaman S, Mulligan CN. Enhancing Osmotic Power Generation and Water Conservation with High-Performance Thin-Film Nanocomposite Membranes for the Mining Industry. Water. 2026; 18(2):248. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020248

Chicago/Turabian StylePakdaman, Sara, and Catherine N. Mulligan. 2026. "Enhancing Osmotic Power Generation and Water Conservation with High-Performance Thin-Film Nanocomposite Membranes for the Mining Industry" Water 18, no. 2: 248. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020248

APA StylePakdaman, S., & Mulligan, C. N. (2026). Enhancing Osmotic Power Generation and Water Conservation with High-Performance Thin-Film Nanocomposite Membranes for the Mining Industry. Water, 18(2), 248. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020248