Research on Mechanical Characteristics of Multi-Stage Centrifugal Pump Rotor Based on Fluid–Structure Interaction

Abstract

1. Introduction

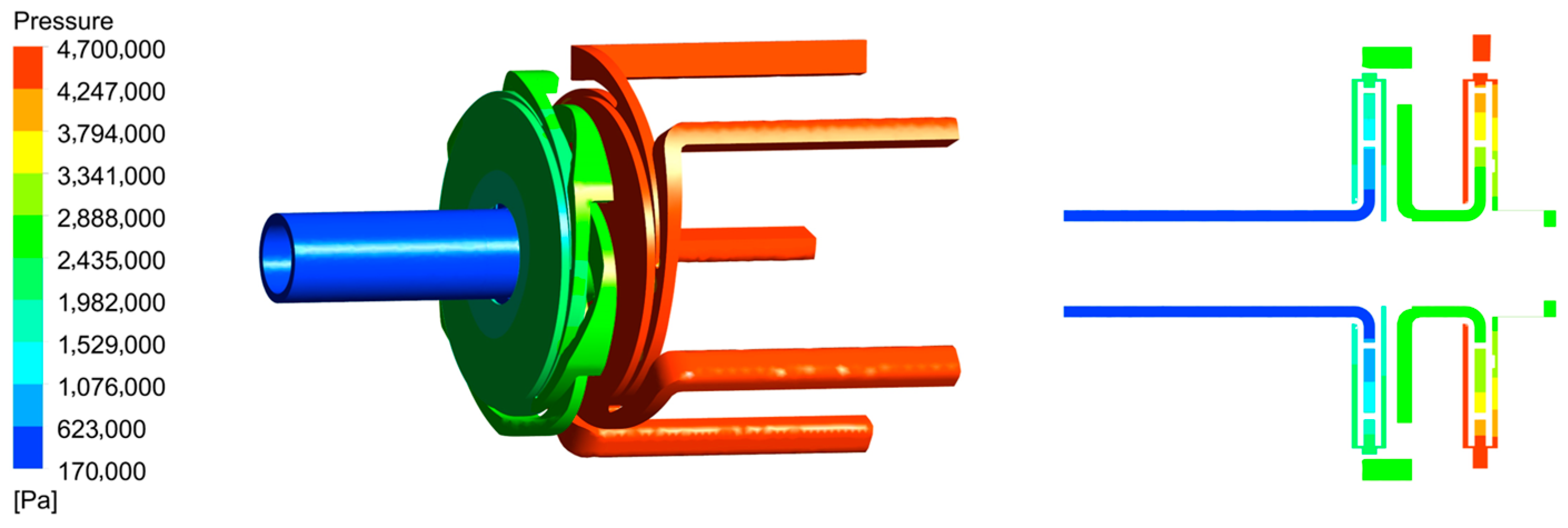

2. Numerical Simulation

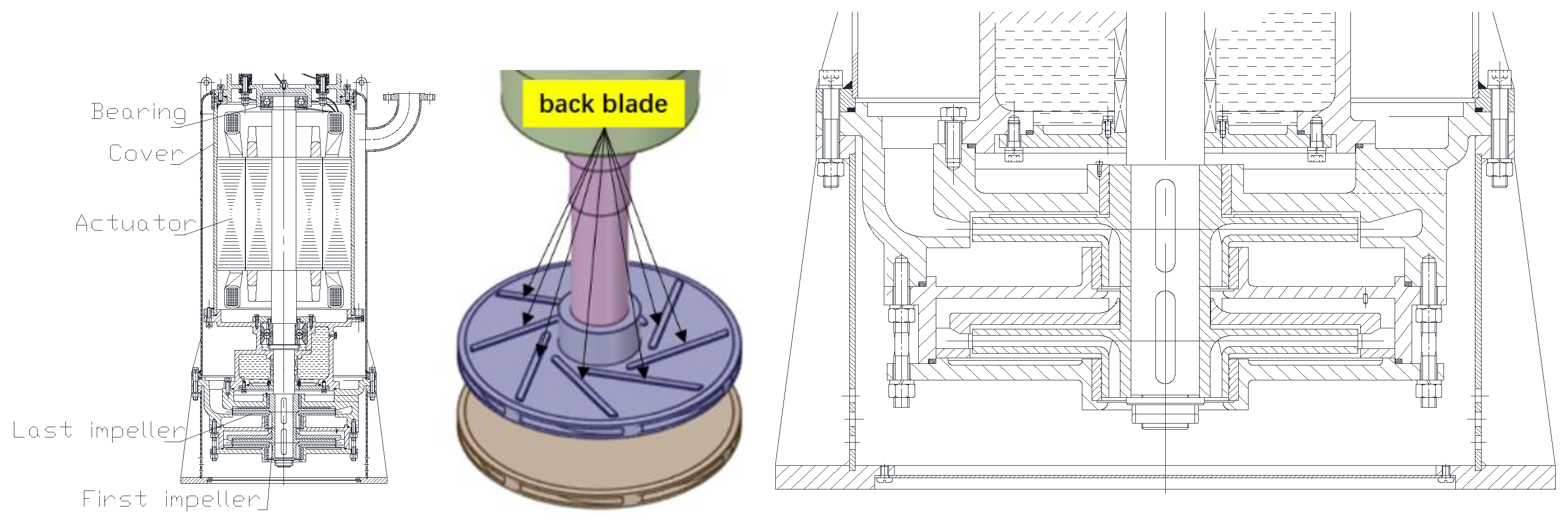

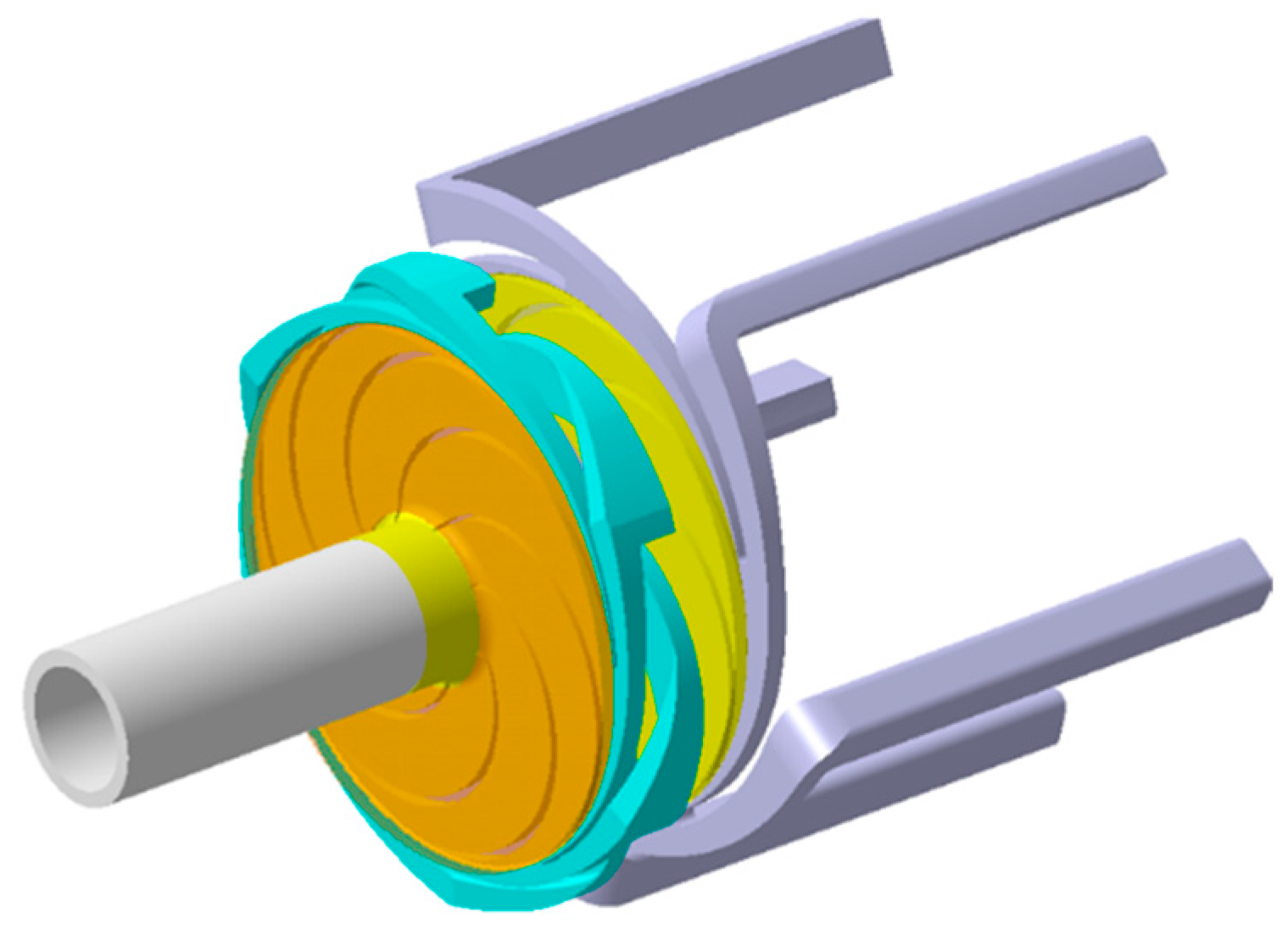

2.1. Computational Modeling

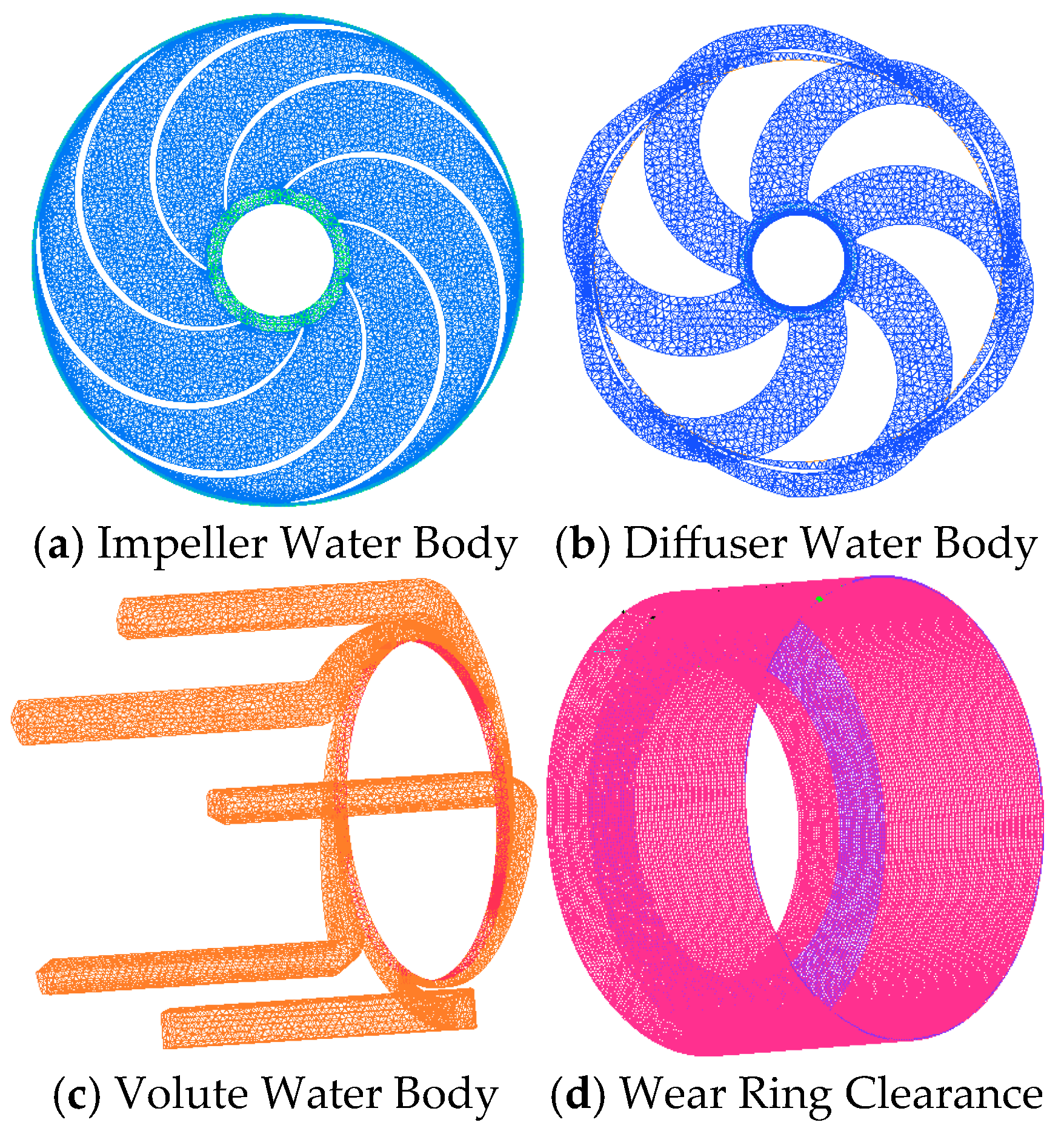

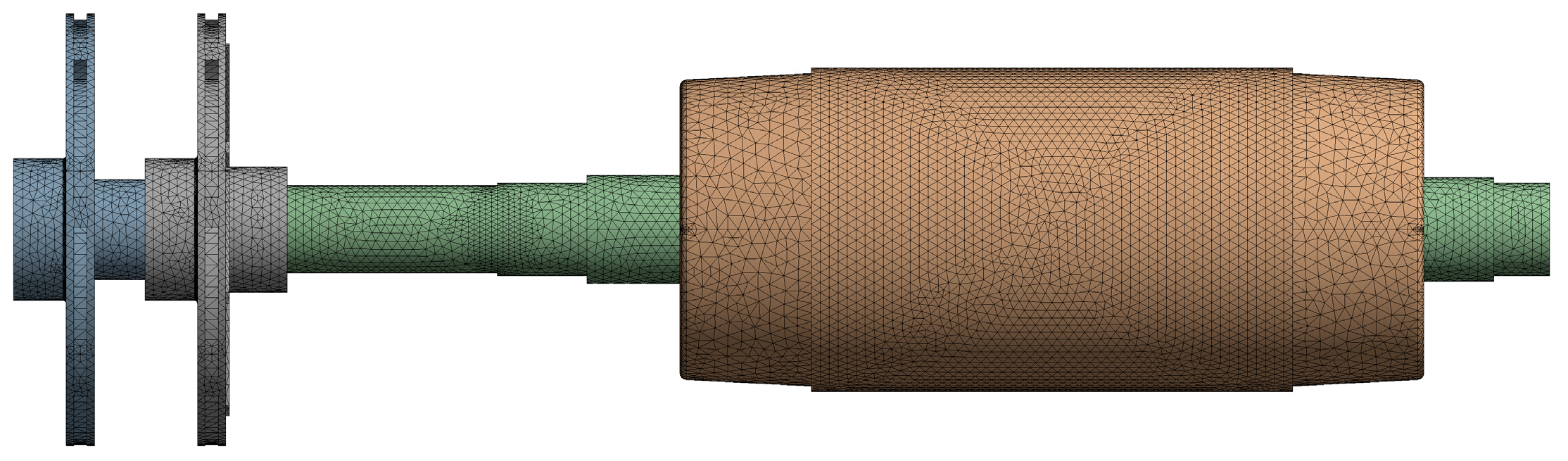

2.2. Mesh Generation

2.3. Boundary Condition Configuration and Model Selection [26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33]

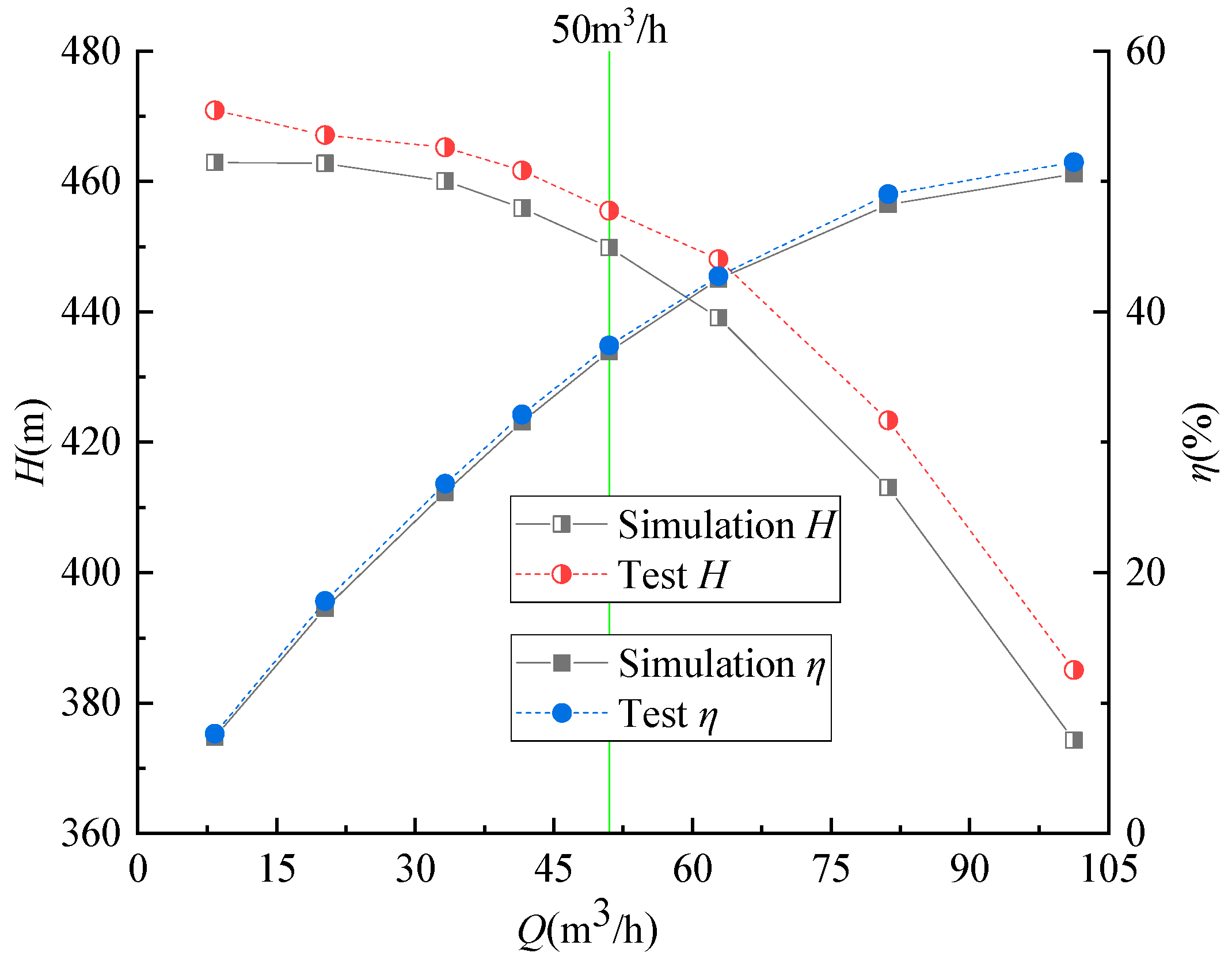

2.4. Validation of Numerical Calculations

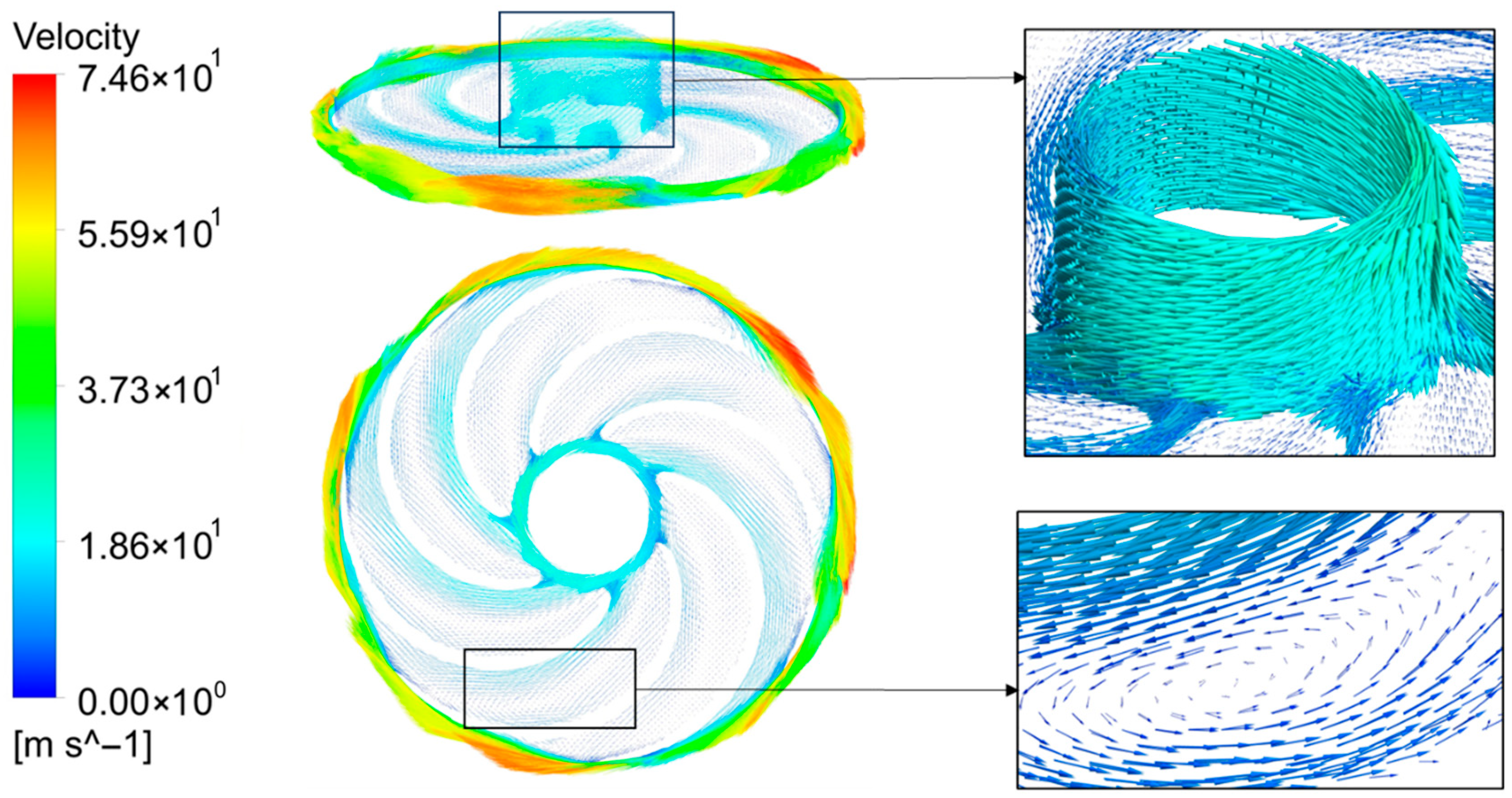

2.5. Analysis of the Internal Flow Field

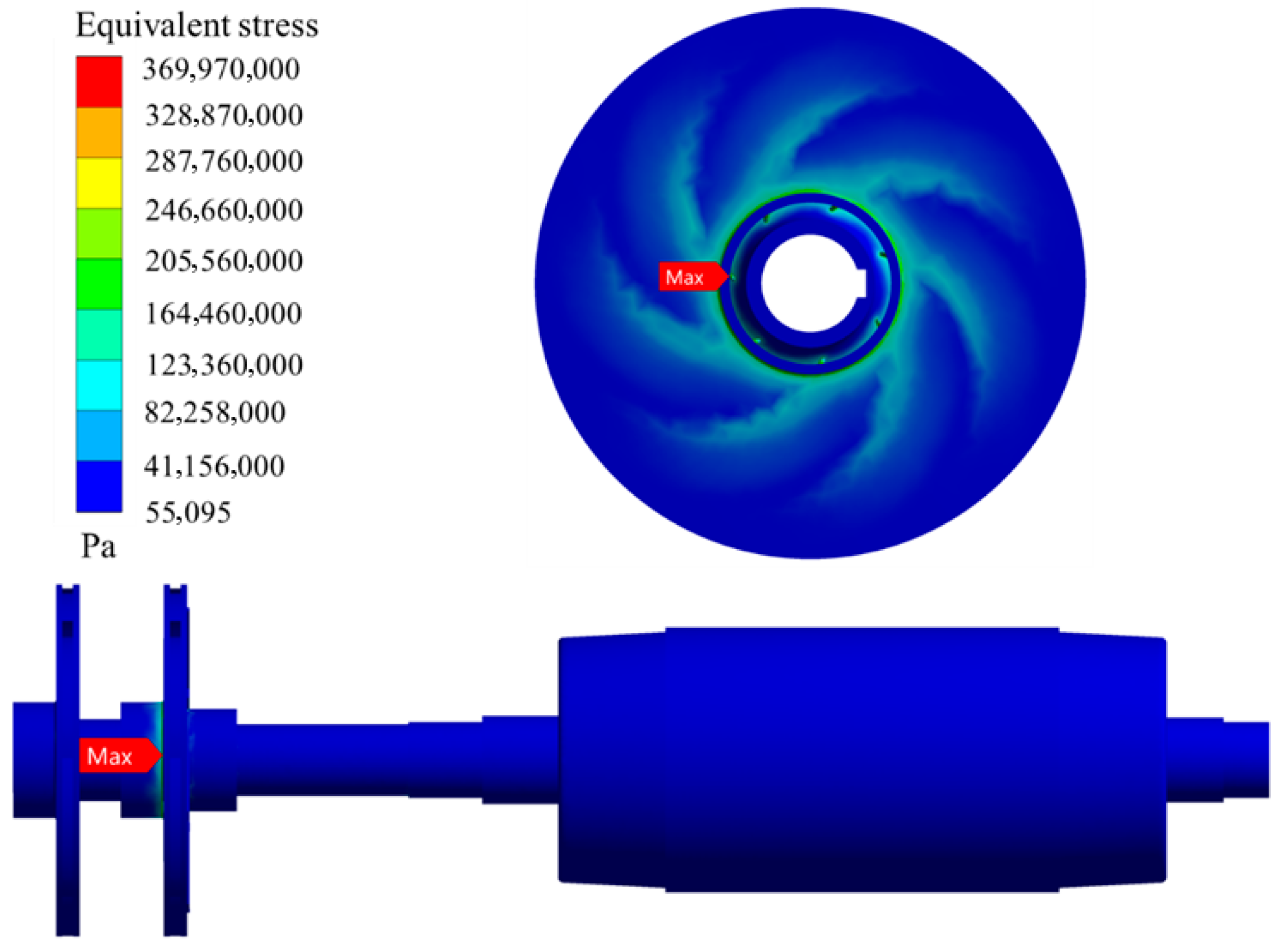

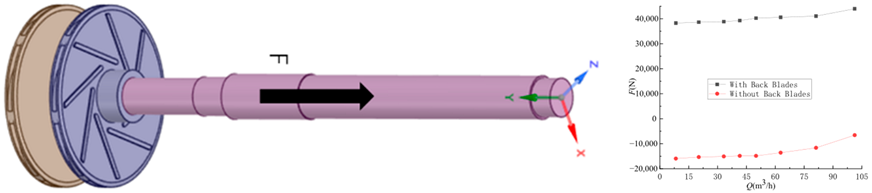

3. Calculation and Analysis of Axial Force [23,24]

3.1. Formula-Based Calculation of Axial Force for Rotor Systems Equipped with Back Blades

3.2. Numerical Simulation-Based Calculation of Rotor System Axial Force

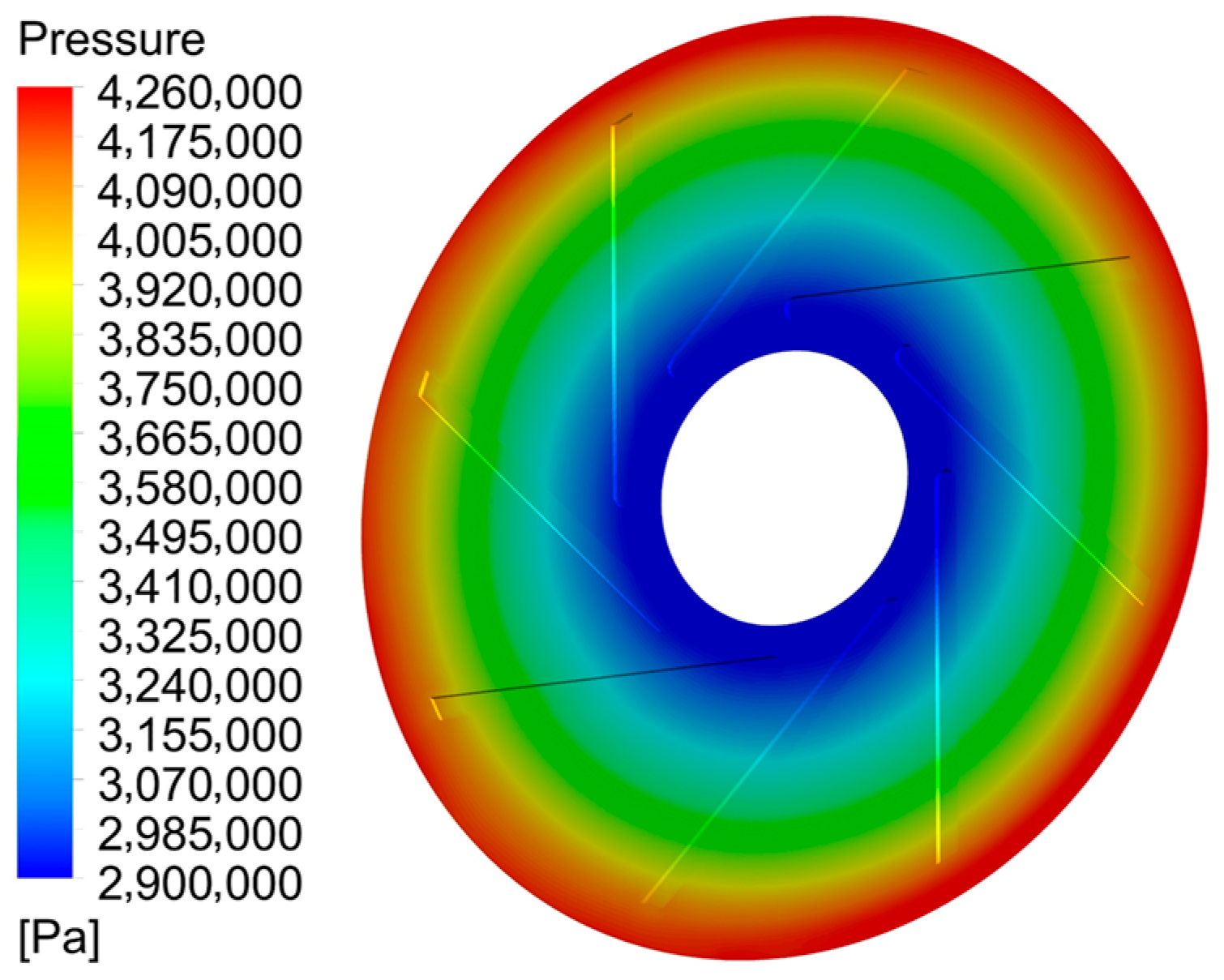

3.2.1. Calculation of Axial Force for Rotor Systems Equipped with Back Blades

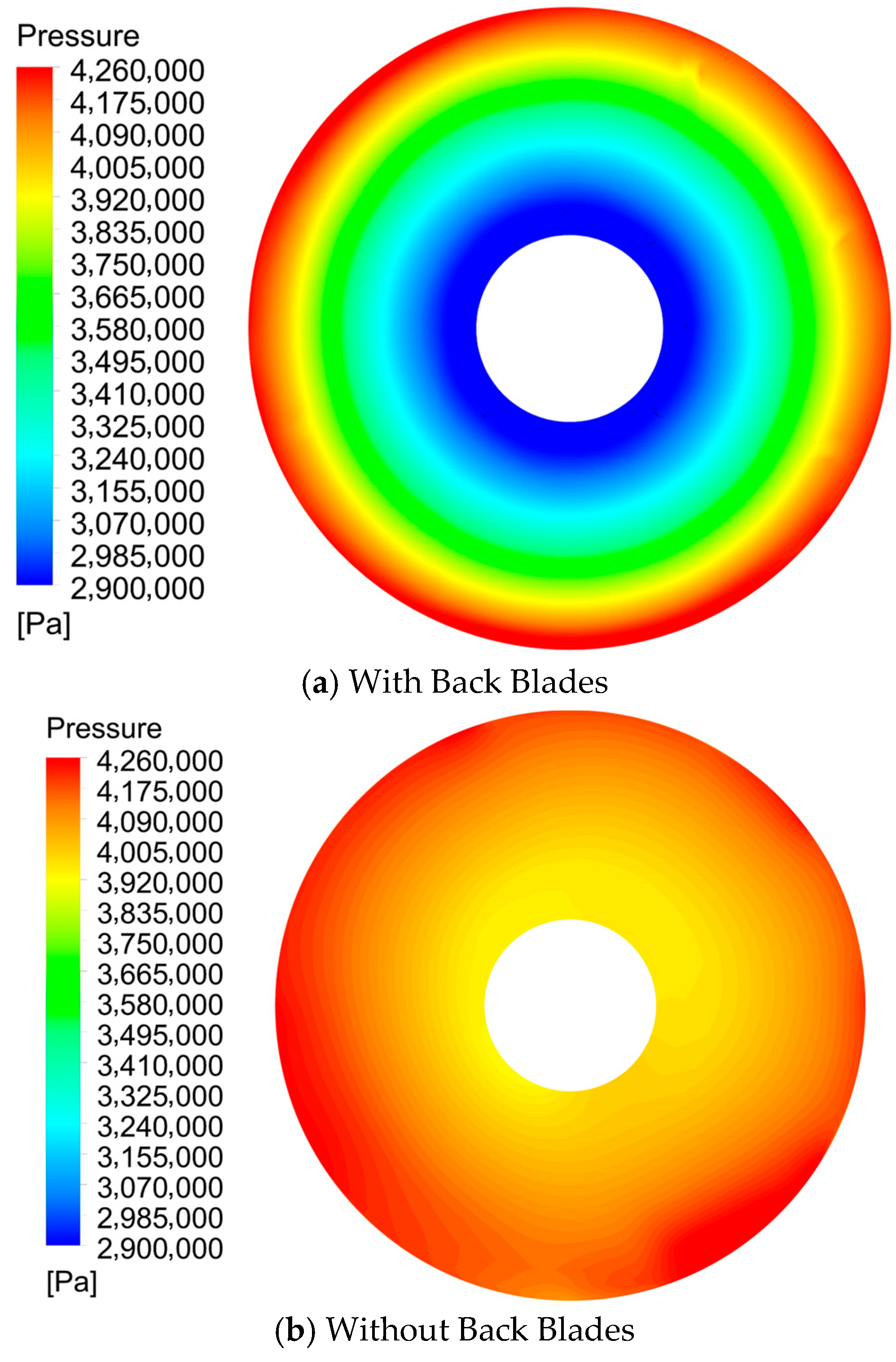

3.2.2. Calculation of Axial Force for Rotor Systems Without Back Blades

3.2.3. Comparative Analysis of Axial Forces

4. Rotor Dynamic Calculation and Analysis

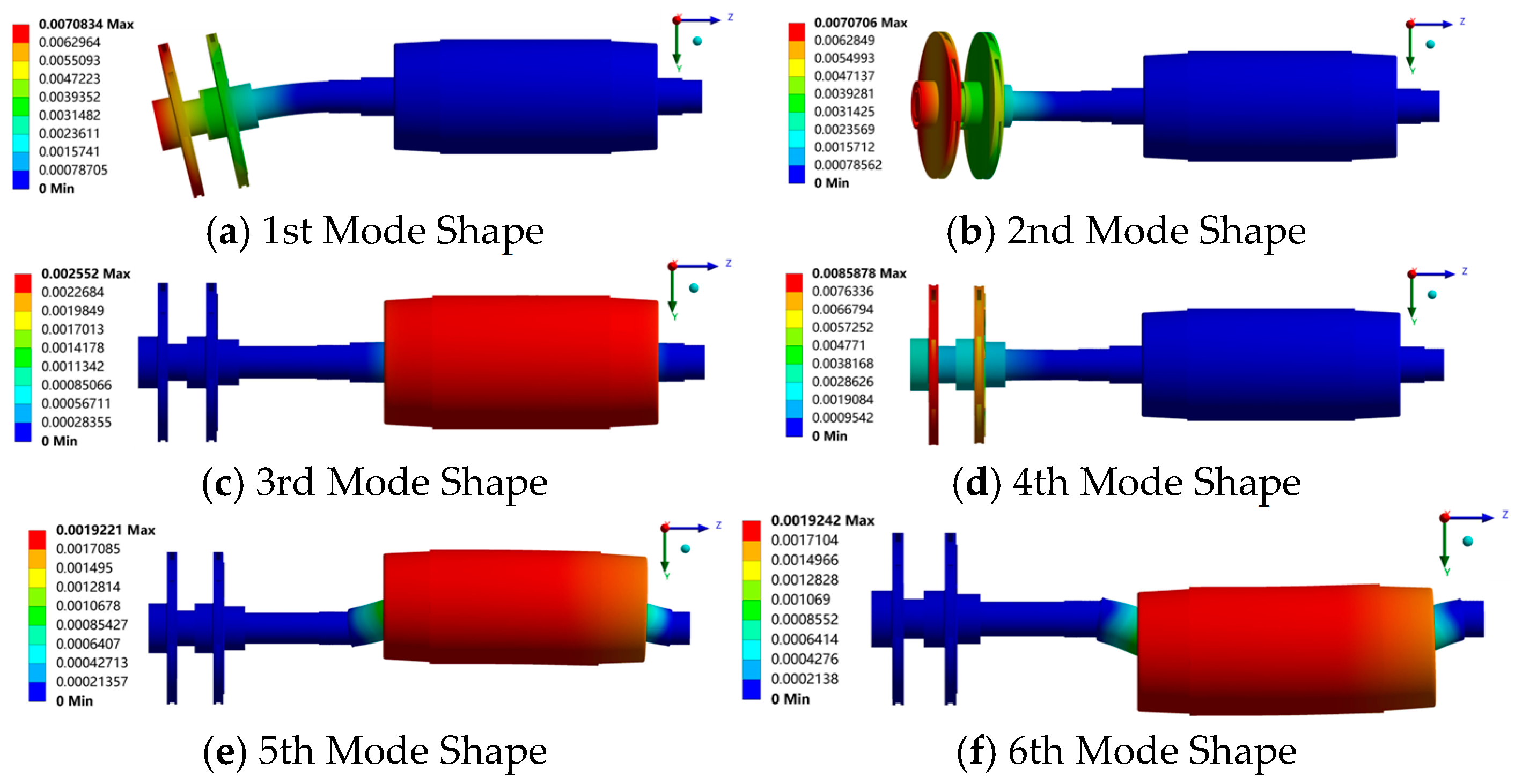

4.1. Modal Analysis of the Pump Rotor System

4.2. Critical Speed Analysis of the Rotor

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Under the design conditions, the numerical simulation results of the two-stage centrifugal pump equipped with auxiliary blades are in good agreement with the experimental data, which validates its feasibility for axial force calculation. For the two-stage centrifugal pump with back blades, the flow field in the region adjacent to the back blades is relatively complex, and the numerical simulation method yields more accurate results than the analytical formula method.

- (2)

- In the absence of back blades, the flow of fluid in the rear cavity of the multi-stage centrifugal pump impeller is relatively stable. The deviation between the numerical simulation results and the analytical formula results is relatively small, accounting for 27.6% of that observed with back blades. Thus, the analytical formula can be employed for rapid calculation to save computational time. After adding back blades, the central pressure of the fluid in the impeller rear cavity decreases significantly, while a distinct high-pressure zone is formed at the outer side. The pressure gradient exhibits a similar trend to that generated by the impeller blades, and the accuracy of the traditional analytical formula for axial force calculation is relatively low under this condition.

- (3)

- The rotor system of the two-stage centrifugal pump exhibits a phenomenon where two adjacent orders of natural frequencies correspond to similar mode shapes, with a frequency difference of less than 1 Hz. This phenomenon is observed for the first- and second-order, as well as the fifth- and sixth-order natural frequencies. Resonance induced by the first-order natural frequency occurs at the cantilever end of the rotor system. The first-order critical speed can be improved by enhancing the shaft stiffness, thereby enhancing the stability of the rotor system.

- (4)

- When two adjacent orders of natural frequencies correspond to similar mode shapes, the directions of the two mode shapes are mutually perpendicular. Due to the inherent speed fluctuation and tolerance of the rotor system, alternating critical speeds may occur when the rotor operates near this frequency range. This phenomenon of mutually perpendicular mode shape variations should be considered during the design phase.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Qian, C.; Luo, X.; Yang, C.; Wang, B. Multistage pump axial force control and hydraulic performance optimization based on response surface methodology. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2021, 43, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, J.; Li, C.; Shi, Y.; Tan, L.; Wang, C. Numerical calculation and balance of axial force of multi-stage centrifugal pump. Gen. Mach. 2016, 11, 80–83. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, J.L.; Liu, Z.L.; Zhao, W.G.; Zhang, S. Experiment of axial force control for centrifugal pump based on compensation trimming method. J. Aerosp. Power 2023, 38, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Mou, J.; Su, M.; Zheng, S.; Lu, H.; Zhao, J. Discussion on the Influence of Back Blade Width of Centrifugal Pump Impeller on Balanced Axial Force. Water Pump Technol. 2011, 36, 24–27. [Google Scholar]

- He, X.; Liu, H.; Tan, M.; Wang, K.; Wu, X. The influence of impeller back blade shape on the performance of molten salt pumps. J. Irrig. Drain. Mech. Eng. 2017, 35, 289–295. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, L.; Yao, S.; Zhao, J.; Mu, J.; Shen, B.; Zhang, H.; Wu, T.; Wu, D. Research on axial force balancing device for large vertical multistage centrifugal pumps. Fluid Mach. 2024, 52, 56–62. [Google Scholar]

- Li, R.; Gao, Y.; Cheng, X.; Han, W.; Guo, L. Numerical calculation for effects of impeller Back pump out vanes on axial thmst in screw centrifugal pump. J. Mech. Eng. 2012, 48, 156–161. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Chen, T.; Lu, W. Experiment and analysis for effects of impeller back Vanes on axial thrust of centrifugal pump. Drain. Irrig. Mach. 2019, 37, 1013–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, P.; Ma, G.; Yan, S.; Yang, D.; Wang, D.; Pan, H. Research on axial force testing technology of impeller of fuel centrifugal pump. Chin. J. Appl. Mech. 2024, 41, 509–515. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, H.; Jiang, X.; Lang, T.; Zhou, C.; Cao, L.; Zhang, D.; Hu, J. Dynamic characteristics of bearing-rotor system of turbocompressor pump. J. Drain. Irrig. Mach. Eng. 2021, 39, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q. Study on rotor dynamic model of large-scale pump-turbine unit. In Proceedings of the 2013 Annual Conference of the Chinese Society for Electrical Engineering, Chengdu, China, 19–21 November 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.; Xu, Y.; Yin, X. Second-order perturbation identification of rotor dynamic parameters of boiler feed pump. J. Vib. Meas. Diagn. 2004, 24, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.; Zhao, W.; Yan, X.; Wei, J.; Chen, Y. Axiomatic design method for rotor dynamics of high-speed turbopump considering multi-source information coupling. J. Mech. Eng. 2015, 51, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, A.; Mahapatra, A.; Bagal, D.K.; Barua, A.; Jeet, S.; Patnaik, D. Comparative evaluation of 4-cylinder CI engine camshaft based on FEA using different composition of metal matrix composite. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 50, 692–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.; Roy, A.K.; Kumar, K. Design analysis of mixed flow pump impeller blades using ANSYS and prediction of its parameters using artificial neural network. Procedia Eng. 2014, 97, 2022–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bapat, A.; Goilkar, S.S. Design and modal analysis of screw agitator and arm followed by fabrication and installation for dry mixing of ingredients to make ready to mix drink powders. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 80, 1049–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Luo, Y.; Umar, B.M.; Wang, W.; Wang, Z. Influence of structural parameters on the modal characteristics of a Francis runner. J. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2021, 131, 105853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Han, B.; Le, Y. Modeling method of the modal analysis for turbomolecular pump rotor blades. Vacuum 2017, 144, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.Y.; Yue, Y.; Li, Z.B.; Wu, H.; Jin, Z.J.; Qian, J.Y. Modal and structural analysis on a main feed water regulating valve under different loading conditions. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2021, 159, 108309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyankumar, R.; Mohanavel, V.; Vinoth, N.; Vinoth, T. Modeling and assessment of pump impeller. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 33, 3226–3233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, S.; Roy, A.K.; Kumar, K. Material selection for blades of mixed flow pump impeller using ANSYS. Mater. Today Proc. 2015, 2, 2022–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chteauvert, T.; Tessier, A.; St-Amant, Y.; Nicolle, J.; Houde, S. Parametric study and preliminary transposition of the modal and structural responses of the Tr-FRANCIS turbine at speed-no-load operating condition. J. Fluids Struct. 2021, 106, 103382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gantar, M.; Florjancic, D.; Sirok, B. Hydraulic Axial Thrust in Multistage Pumps—Origins and Solutions. J. Fluids Eng. 2002, 124, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X. Handbook of Modern Pump Technology; Aerospace Press: Beijing, China, 1995; ISBN 7800347974. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, L.; He, S.; Li, W.; Shi, W.; Li, S.; Li, H.; Agarwal, R. Exploration of blade thickness in suppressing rotating stall of mixed flow pump. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2023, 48, 8227–8251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Wang, X.; Shi, L.; Tang, F. Hydraulic performance and flow patterns of axial-flow pumps with axial stacking of different airfoil series. J. Drain. Irrig. Mach. Eng. 2022, 40, 217–222. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, L.; Li, W.; Shi, W.; Chang, H.; Yang, Z. Diagnosis of internal energy characteristics of mixed-flow pump within stall region based on entropy production analysis model. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2020, 117, 104784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Du, X.; Wu, X.; Tan, M. Numerical simulation on gas-phase characteristics of gas-liquid two-phase flow in pump. J. Drain. Irrig. Mach. Eng. 2022, 40, 238–243. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, L.; He, S.; Li, Y.; Li, W.; Shi, W.; Li, S.; Yangyang Yang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Agarwal, R.K. Investigation of energy loss mechanism of shroud region in A mixed-flow pump under stall conditions. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part A J. Power Energy 2023, 237, 1235–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Dai, Q.; Zheng, Y.; Wu, D.; Wei, W. Pressure pulsation characteristics and improvement methods of axial extension pump. J. Drain. Irrig. Mach. Eng. 2022, 40, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Huang, Y.; Ji, L.; Ma, L.; Agarwal, R.K.; Awais, M. Prediction model for energy conversion characteristics during transient processes in a mixed-flow pump. Energy 2023, 271, 127082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, D.; Pan, Z.; Yang, B. Characteristics of gas-liquid two-phase flow in self-priming pump. J. Drain. Irrig. Mach. Eng. 2022, 40, 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Stel, H.; Ofuchi, E.M.; Chiva, S.; Morales, R.E. Numerical simulation of gas-liquid flows ina centrifugal rotor. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2020, 221, 115692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Wang, P.; Hu, X. Modal analysis of the structure of fuel pump regulator based on Virtual.Lab. J. Nanjing Univ. Aeronaut. Astronaut. 2021, 53, 537–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, S.; Hu, S. Identification and influence analysis of dynamic characteristic parameters of axial piston pump based on the airborne model. J. Propuls. Technol. 2023, 44, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, K.; Kong, F.; Zhou, Y.; Qian, W.; Wang, J. Modal calculation and analysis of compact magnetic drive pump. J. Drain. Irrig. Mach. Eng. 2020, 38, 781–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Shi, W.; Zhang, D.; Chen, Z.; Huang, J. Modal analysis of rotor components of LNG cryogenic submersible pump based on heat-fluid-solid coupling. J. Drain. Irrig. Mach. Eng. 2019, 37, 211–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Ji, Y.; Wu, X.; Tan, M.; Wang, K. Critical speed analysis of rotor of eight-stage centrifugal pump. J. China Rural. Water Hydropower 2017, 193, 181–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Axial Force (N) (Negative Values Denote a Downward Direction) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Structure | Formula-Based Explanation | Numerical Simulation | Difference |

| With Back Blades | 11,397 | −40,237 | 51,634 |

| Without Back Blades | 29,077 | 14,842 | 14,235 |

| ||||||||

| Flow Q (m3/h) | 8.34 | 20.26 | 33.26 | 41.55 | 50 | 62.83 | 81.18 | 101.27 |

| With Back Blades | 38,265 | 38,618 | 38,847 | 39,275 | 40,237 | 40,579 | 41,070 | 43,997 |

| Without Back Blades | −15,926 | −15,323 | −15,075 | −14,849 | −14,842 | −13,556 | −11,648 | −6574 |

| No. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Frequencies | 119.62 | 119.75 | 215.93 | 228.94 | 329.00 | 329.34 |

| Critical Speeds | 7177.2 | 7185 | 12,955.8 | 13,736.4 | 19,740 | 19,760.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhao, H.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yang, Z.; Li, W. Research on Mechanical Characteristics of Multi-Stage Centrifugal Pump Rotor Based on Fluid–Structure Interaction. Water 2026, 18, 229. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020229

Zhao H, Gao Y, Zhang X, Yang Z, Li W. Research on Mechanical Characteristics of Multi-Stage Centrifugal Pump Rotor Based on Fluid–Structure Interaction. Water. 2026; 18(2):229. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020229

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Haiyan, Yi Gao, Xiaodi Zhang, Zixing Yang, and Wei Li. 2026. "Research on Mechanical Characteristics of Multi-Stage Centrifugal Pump Rotor Based on Fluid–Structure Interaction" Water 18, no. 2: 229. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020229

APA StyleZhao, H., Gao, Y., Zhang, X., Yang, Z., & Li, W. (2026). Research on Mechanical Characteristics of Multi-Stage Centrifugal Pump Rotor Based on Fluid–Structure Interaction. Water, 18(2), 229. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020229