Temporal and Spatial Variation Pattern of Groundwater Storage and Response to Environmental Changes in Shandong Province

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Sources

2.3. Research Methods

2.3.1. Singular Spectrum Analysis Method

2.3.2. Water Balance Equation

2.3.3. Linear Regression Trend Analysis

2.3.4. Mann–Kendall Test

2.3.5. Quantifying the Relative Contributions of Climate and Human Activities on GWSA

2.3.6. Spearman’s Rank Correlation Analysis

3. Results

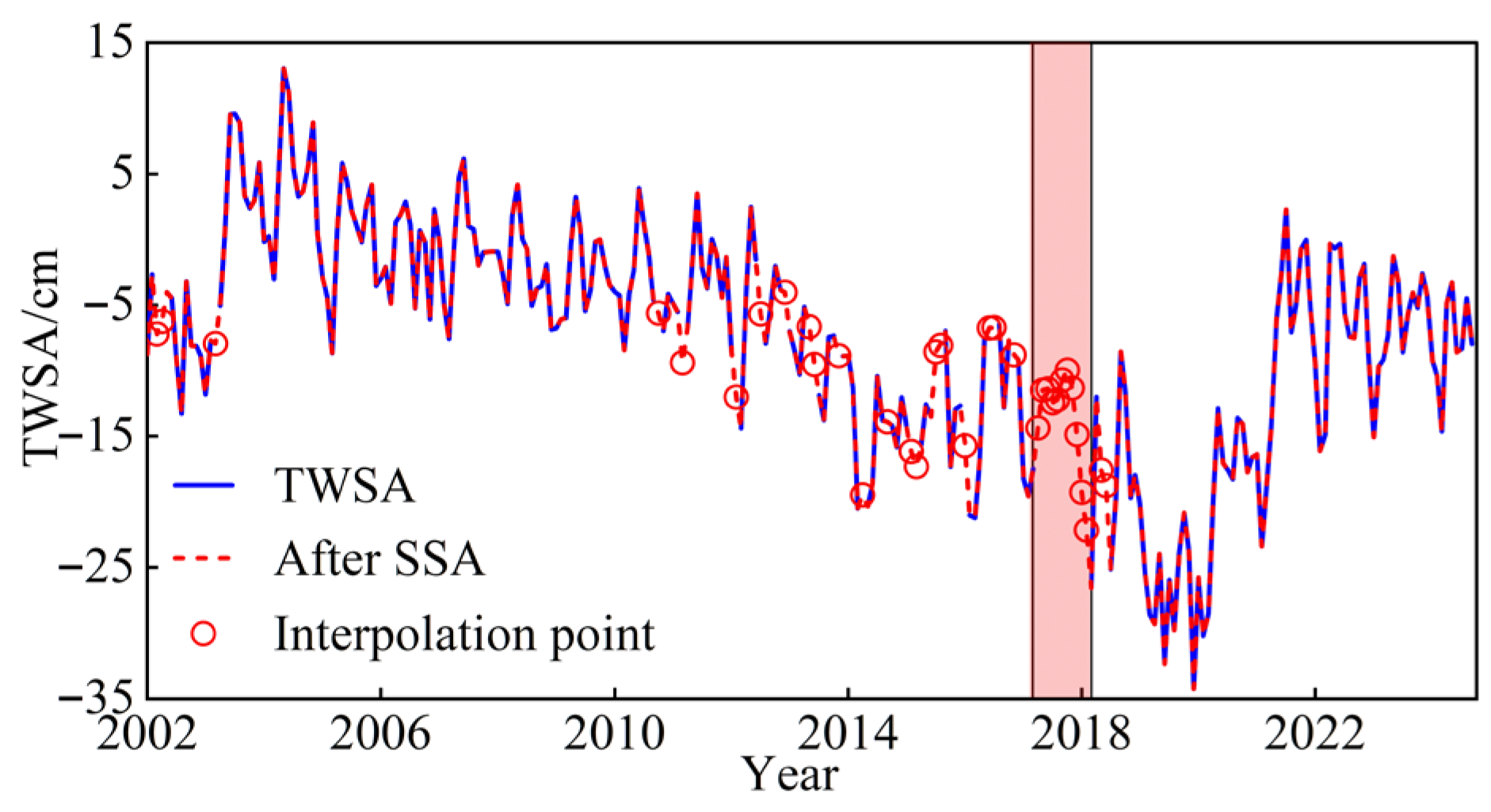

3.1. Reconstruction of TWSA Series Using Singular Spectrum Analysis

3.2. Spatiotemporal Variation Patterns of GWSA in Shandong Province

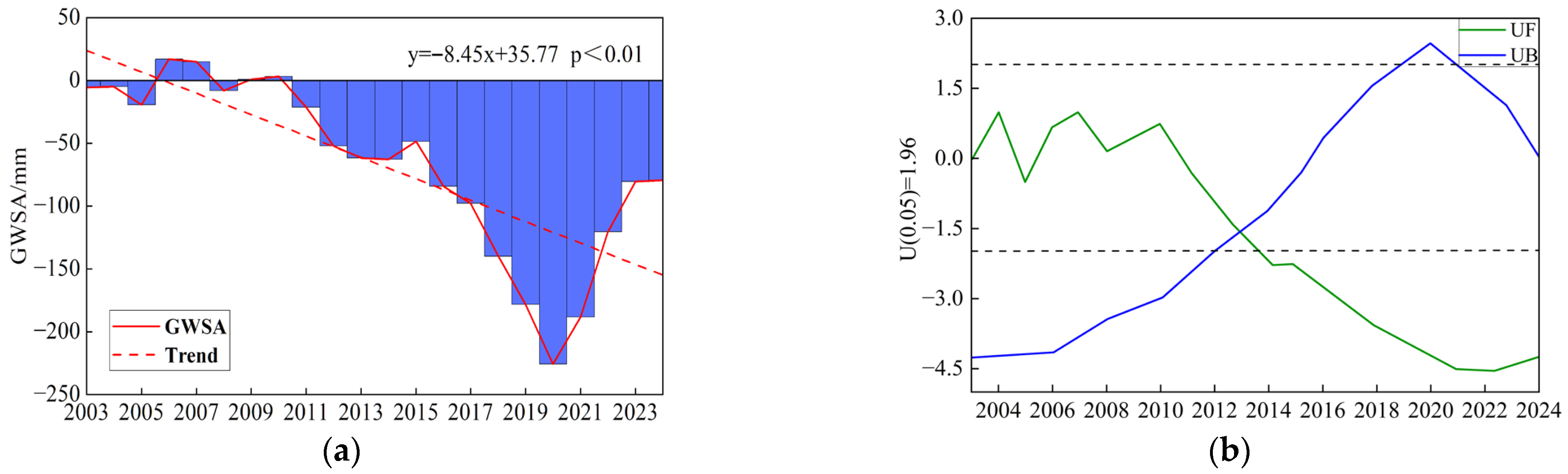

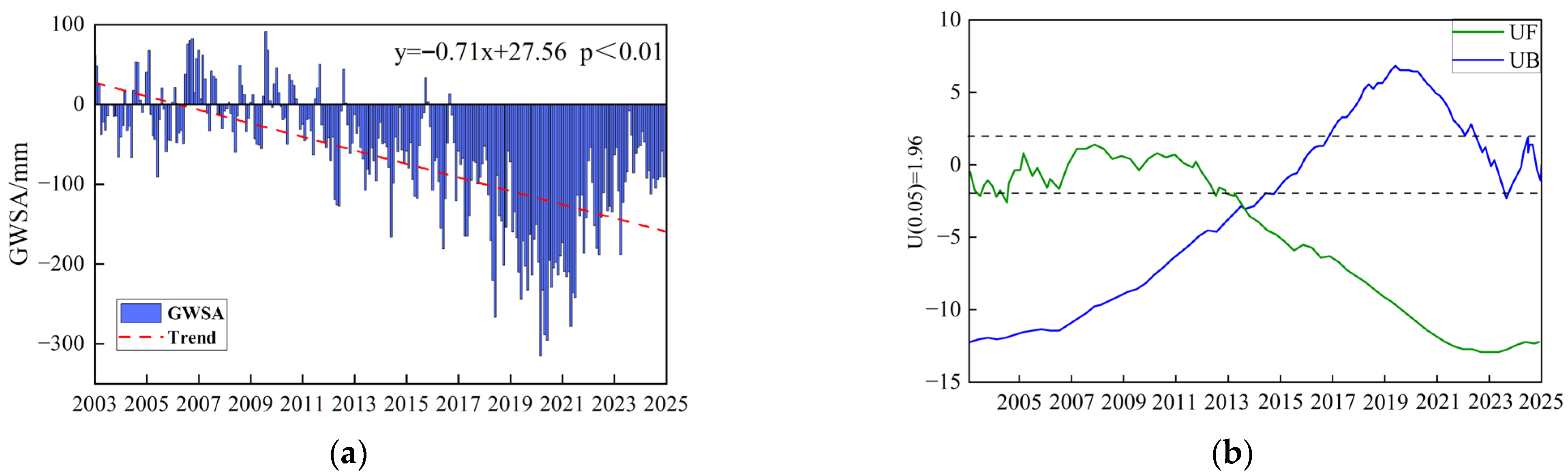

3.2.1. Temporal Variation Patterns

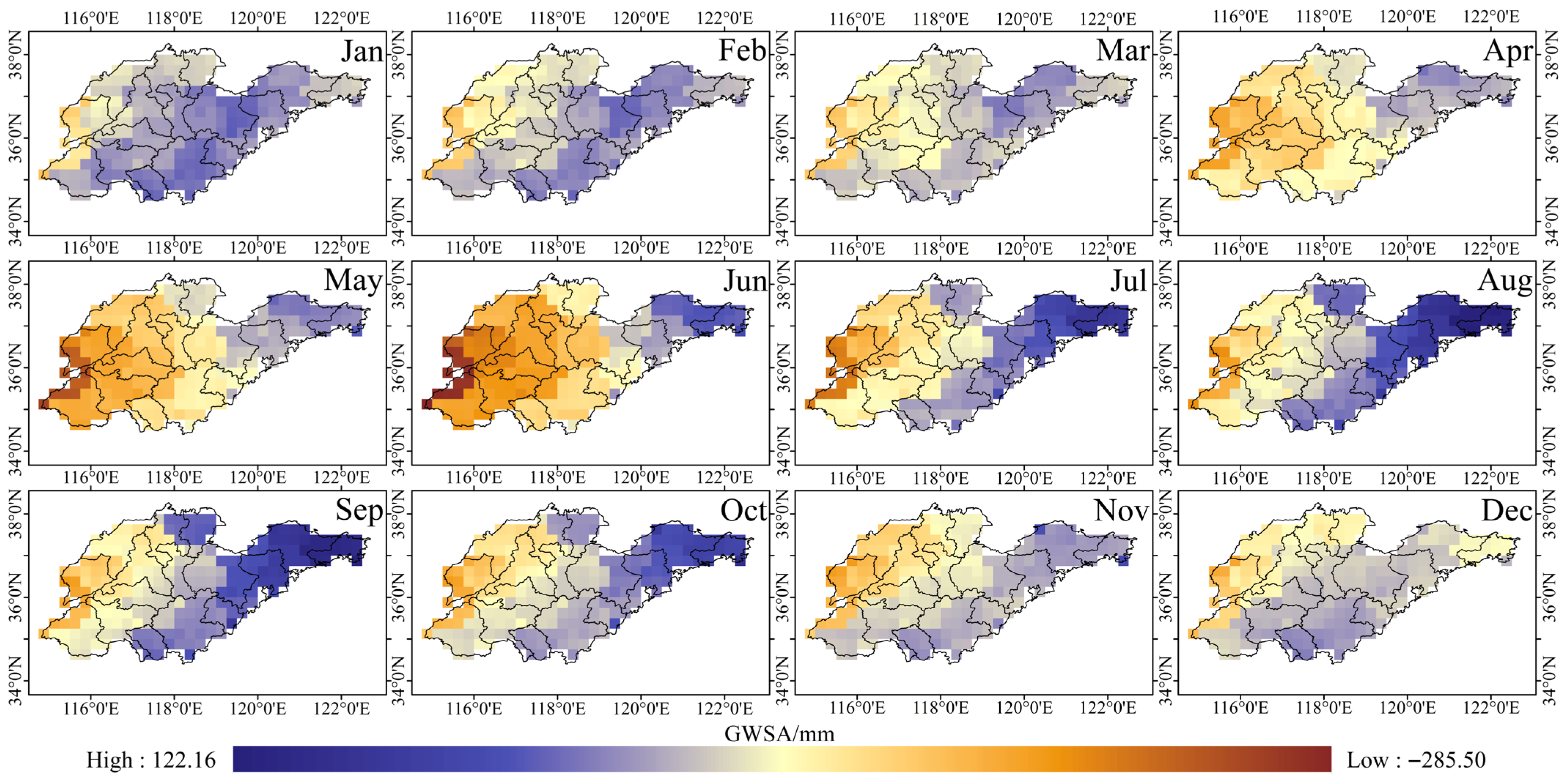

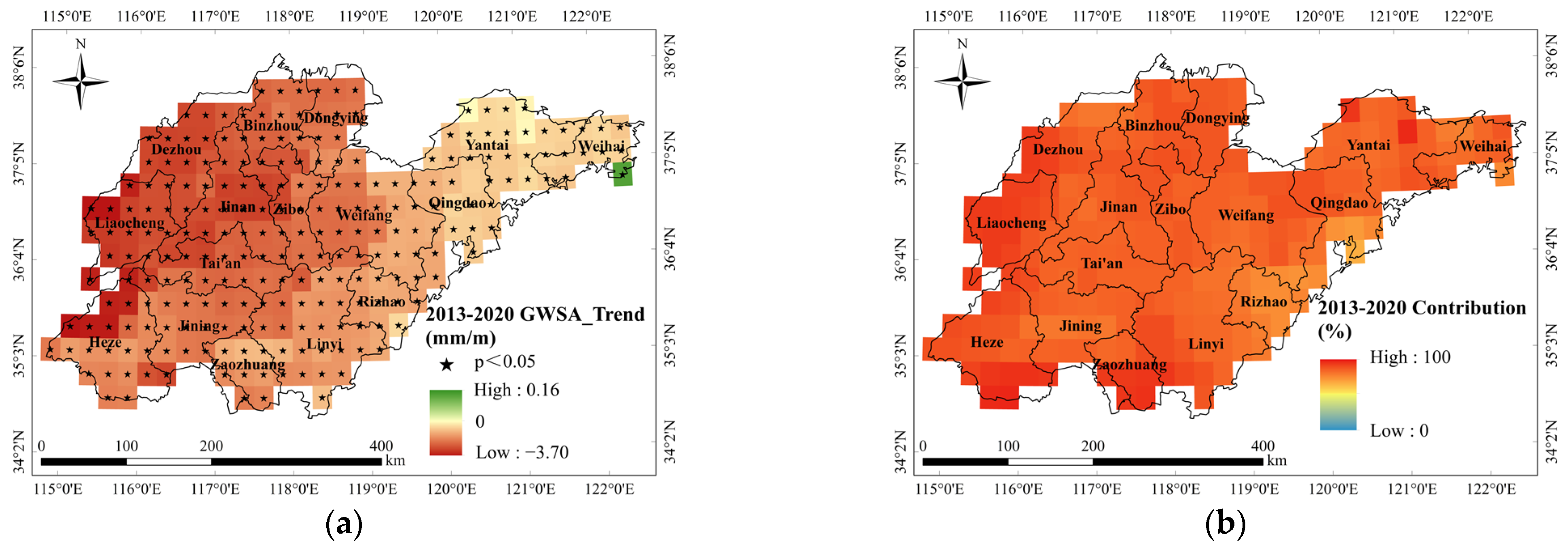

3.2.2. Spatial Variation Patterns

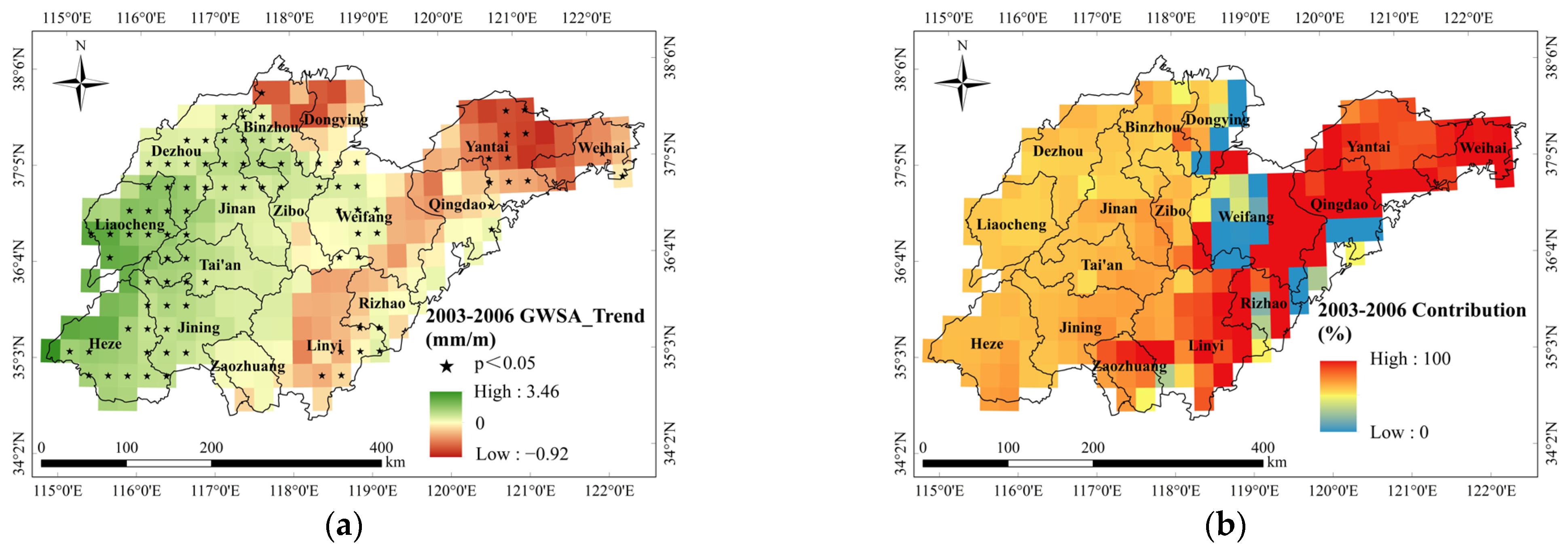

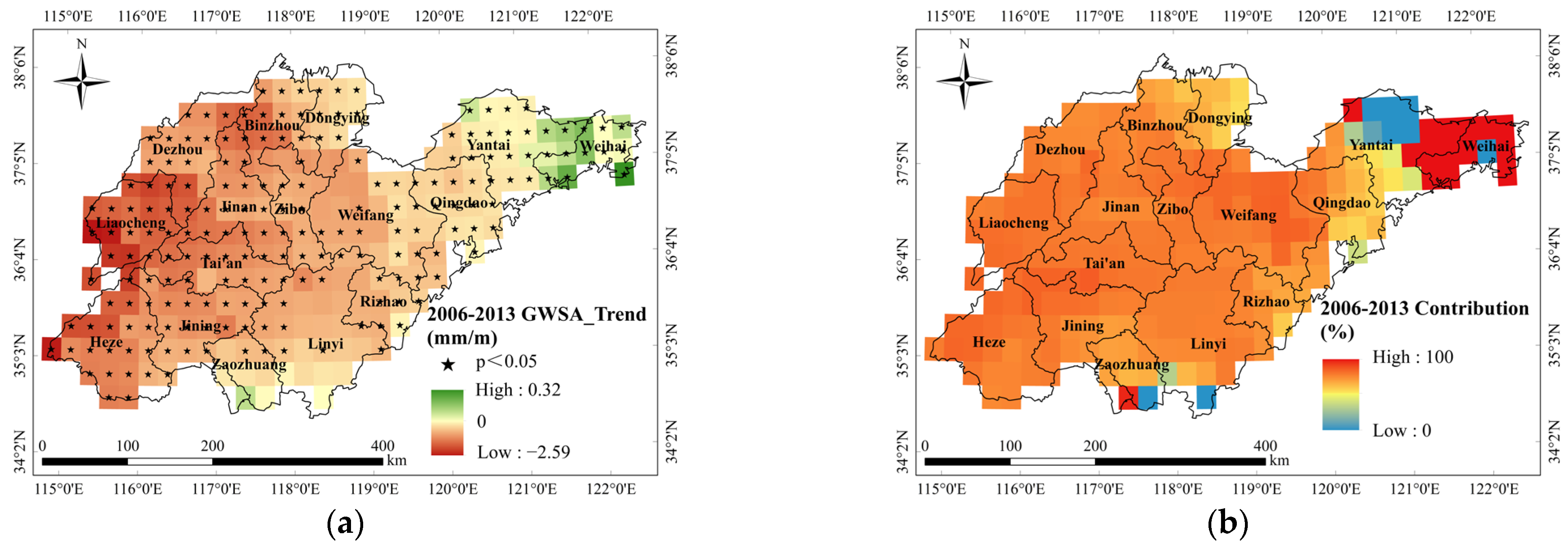

3.3. Contribution Rate of Human Activities

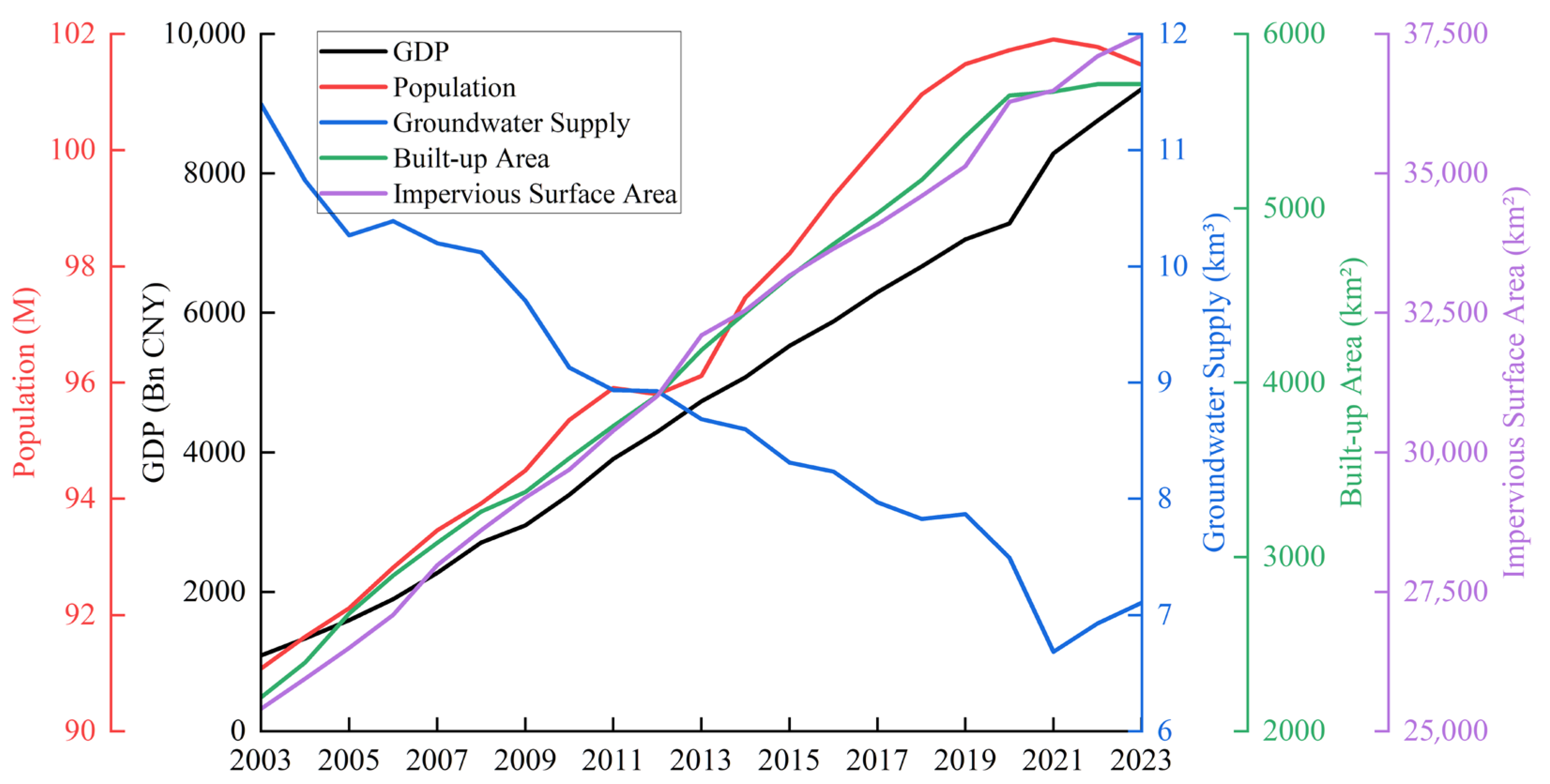

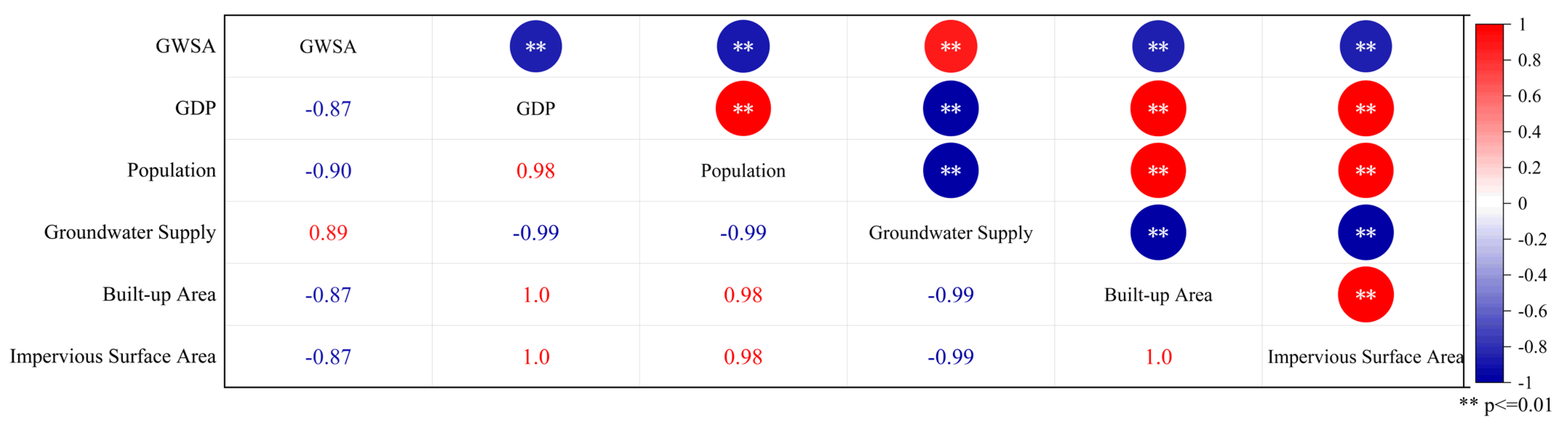

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- The interannual variation trend of GWSA in Shandong Province from 2003 to 2024 exhibited a significant overall decreasing trend, with a monthly change rate of −0.71 mm/m (p < 0.01) and an annual change rate of −8.45 mm/a (p < 0.01). The GWSA changes underwent a process of initial stability, followed by a sharp decline, and then a slight recovery. The MK test identified 2013 as the abrupt change year.

- Groundwater storage in Shandong Province exhibits significant seasonal differentiation, characterized by “spring drought, summer intensity, autumn stability, and winter moderation,” generally showing a pattern of initial decrease followed by an increase, with key replenishment occurring in summer and autumn. The groundwater system is most arid in spring, with an average value of −86.76 mm. Summer is both the primary period for extreme negative anomalies (reaching the monthly average minimum of −126.41 mm in June) and a critical period for potential positive recharge (reaching the monthly average maximum of −34.30 mm in August). Autumn and winter are relatively abundant, with averages of −52.39 mm and −49.20 mm, respectively. This highlights the importance of seasonal water resource allocation and management.

- Spatially, the decreasing trend shows a distinct pattern of diminishing from west to east. This indicates that the spatial differentiation pattern of GWSA in Shandong Province results from the interaction of geographical setting (coastal/inland location), hydrogeological conditions, and human activity intensity. Inland areas exhibit higher groundwater vulnerability and require targeted management.

- Human activities have progressively become the decisive factor driving GWSA changes in Shandong Province. From 2003 to 2024, the average contribution rate of human activities to GWSA changes reached 86.11%, and the areal proportion where human activities served as the decisive factor (contribution rate > 80%) increased from 54.16% during 2003–2006 to 99.58% during 2020–2024. The influence of climate change has gradually diminished in its ability to dominate the GWSA trend in Shandong Province. Future efforts should place greater emphasis on the macro-regulation of human subjective initiative in addressing groundwater storage issues.

- The impact of human activities exhibits dual-directionality and phase-specific characteristics. Contribution rate analysis indicates that the impact of human activities is not solely negative consumption but possesses significant potential for bidirectional regulation. Evidence of this was apparent even in the initial phase (2003–2006); in both rapidly developing coastal areas and inland regions where human activities dominated GWSA changes, the positive and negative GWSA trend values differed significantly. During the rapid consumption phase (2013–2020), human activities were the dominant negative driver leading to systematic groundwater depletion. In contrast, during the recovery period (2020–2024), human activities became the key positive driver promoting the recovery of groundwater storage. This finding challenges the simplistic perception that “human activities equate to resource depletion” and emphasizes the effectiveness of scientific management and policy interventions.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kuang, X.; Liu, J.; Scanlon, B.R.; Jiao, J.J.; Jasechko, S.; Lancia, M.; Biskaborn, B.K.; Wada, Y.; Li, H.; Zeng, Z.; et al. The Changing Nature of Groundwater in the Global Water Cycle. Science 2024, 383, eadf0630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodell, M.; Famiglietti, J.S.; Wiese, D.N.; Reager, J.T.; Beaudoing, H.K.; Landerer, F.W.; Lo, M.-H. Emerging Trends in Global Freshwater Availability. Nature 2018, 557, 651–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Graaf, I.E.M.; Gleeson, T.; (Rens) Van Beek, L.P.H.; Sutanudjaja, E.H.; Bierkens, M.F.P. Environmental Flow Limits to Global Groundwater Pumping. Nature 2019, 574, 90–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, D.; Pan, Y.; Zhou, J.; Chen, Y.; Hou, X.; Hong, Y.; Scanlon, B.R.; Longuevergne, L. Global Analysis of Spatiotemporal Variability in Merged Total Water Storage Changes Using Multiple GRACE Products and Global Hydrological Models. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 192, 198–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monir, M.M.; Sarker, S.C.; Islam, A.R.M.T. A Critical Review on Groundwater Level Depletion Monitoring Based on GIS and Data-Driven Models: Global Perspectives and Future Challenges. HydroResearch 2024, 7, 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reading, L.; Gurieff, L.B.; Catania, S. Sustainable Groundwater Management through Collaborative Local Scale Monitoring. Water Resour. Manag. 2025, 39, 725–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapley, B.D.; Bettadpur, S.; Ries, J.C.; Thompson, P.F.; Watkins, M.M. GRACE Measurements of Mass Variability in the Earth System. Science 2004, 305, 503–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangdamrongsub, N.; Hwang, C.; Borak, J.S.; Prabnakorn, S.; Han, J. Optimizing GRACE/GRACE-FO Data and a Priori Hydrological Knowledge for Improved Global Terrestial Water Storage Component Estimates. J. Hydrol. 2021, 598, 126463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Nan, Z.; Cheng, G. GRACE Gravity Satellite Observations of Terrestrial Water Storage Changes for Drought Characterization in the Arid Land of Northwestern China. Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 1021–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Famigliett, J.S.; Scanlon, B.R.; Rodell, M. Groundwater Storage Changes: Present Status from GRACE Observations. Surv. Geophys. 2016, 37, 397–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Feng, W.; Bai, H.; Chen, W.; Jiang, Z.; Zhong, M. High-Resolution Terrestrial Water Storage Anomalies and Components in China From GRACE/GFO via Joint Inversion Downscaling. Water Resour. Res. 2025, 61, e2024WR038996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahr, J.; Molenaar, M.; Bryan, F. Time Variability of the Earth’s Gravity Field: Hydrological and Oceanic Effects and Their Possible Detection Using GRACE. J. Geophys. Res. 1998, 103, 30205–30229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Chen, X. Decomposition-Based Reconstruction Scheme for GRACE Data with Irregular Temporal Intervals. J. Hydrol. 2025, 662, 134011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, S.; Sneeuw, N. Filling the Data Gaps Within GRACE Missions Using Singular Spectrum Analysis. JGR Solid Earth 2021, 126, e2020JB021227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodell, M.; Famiglietti, J.S. The Potential for Satellite-Based Monitoring of Groundwater Storage Changes Using GRACE: The High Plains Aquifer, Central US. J. Hydrol. 2002, 263, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitambo, B.M.; Wongchuig, S.; Tshimanga, R.M.; Paris, A.; Blazquez, A.; Moreira, D.; Frappart, F.; Fleischmann, A.S.; Kileshye, J.-M.O.; Tourian, M.J.; et al. Hydrogeological Control of Groundwater Variations in the Congo River Basin Revealed by GRACE Water Storage Change Decomposition. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2025, 62, 102810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashani, A.; Safavi, H.R. Assessing Groundwater Drought in Iran Using GRACE Data and Machine Learning. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 14671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Lin, Z.; Wang, Q.; Yu, Y.; Yu, G. The Spatio-Temporal Evolution of Ecosystem Service Value and Its Driving Factors Analysis in Shandong Province of China. Adv. Space Res. 2025, 77, 1776–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Xu, Y.; Li, C.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X. Characteristics of Groundwater Drought and Its Correlation with Meteorological and Agricultural Drought over the North China Plain Based on GRACE. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 161, 111925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, Z.; Xie, X.; Su, C.; Ge, W.; Pan, H.; Yang, L. Understanding the Evolutionary Processes and Causes of Groundwater Drought Using an Interpretable Machine Learning Model. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 20981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Save, H.; Bettadpur, S.; Tapley, B.D. High-resolution CSR GRACE RL05 Mascons. JGR Solid Earth 2016, 121, 7547–7569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Zhong, Y.; Wu, Y.; Yang, K.; An, Q.; Bai, H.; Liu, S. Quantifying Long-Term Drought in China’s Exorheic Basins Using a Novel Daily GRACE Reconstructed TWSA Index. J. Hydrol. 2025, 655, 132919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, W.; Zhang, P.; Zhao, X. A Comparison of Different GRACE Solutions in Terrestrial Water Storage Trend Estimation over Tibetan Plateau. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodell, M.; Houser, P.R.; Jambor, U.; Gottschalck, J.; Mitchell, K.; Meng, C.-J.; Arsenault, K.; Cosgrove, B.; Radakovich, J.; Bosilovich, M.; et al. The Global Land Data Assimilation System. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2004, 85, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S. High-Spatial-Resolution Monthly Precipitation Dataset over China during 1901–2017. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2019, 11, 1931–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Ding, Y.; Liu, W.; Li, Z. 1 Km Monthly Temperature and Precipitation Dataset for China from 1901 to 2017. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2019, 11, 1931–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huiqun, R.; Xin, H.; Jie, Y.; Guoqing, Z. Improving 30-Meter Global Impervious Surface Area (GISA) Mapping: New Method and Dataset. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2024, 220, 354–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vautard, R.; Yiou, P.; Ghil, M. Singular-Spectrum Analysis: A Toolkit for Short, Noisy Chaotic Signals. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 1992, 58, 95–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassani, H. Singular Spectrum Analysis: Methodology and Comparison. J. Data Sci. 2021, 5, 239–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoellhamer, D.H. Singular Spectrum Analysis for Time Series with Missing Data. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2001, 28, 3187–3190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondrashov, D.; Ghil, M. Spatio-Temporal Filling of Missing Points in Geophysical Data Sets. Nonlin. Process. Geophys. 2006, 13, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broomhead, D.S.; King, G.P. Extracting Qualitative Dynamics from Experimental Data. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 1986, 20, 217–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, H.; Pan, Y.; Zheng, L.; Li, X.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, C.; Huang, Z.; Li, Z.; Wang, H.; Zhou, C. Long-Term Groundwater Storage Changes and Land Subsidence Development in the North China Plain (1971–2015). Hydrogeol. J. 2018, 26, 1417–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, V.; Gudmundsson, L.; Seneviratne, S.I. A Global Reconstruction of Climate-driven Subdecadal Water Storage Variability. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2017, 44, 2300–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Zou, X.; Yi, S.; Sneeuw, N.; Cai, J.; Li, J. Identifying and Separating Climate- and Human-Driven Water Storage Anomalies Using GRACE Satellite Data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 263, 112559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Z. The Relative Roles of Climate Variations and Human Activities in Vegetation Change in North China. Phys. Chem. Earth Parts A/B/C 2015, 87–88, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, H.; Liu, M.; Jia, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Xiao, Y. The Trend of Vegetation Greening and Its Drivers in the Agro-Pastoral Ecotone of Northern China, 2000–2020. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 129, 108004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Pei, H.; Shen, Y. Evaluating Dynamics of GRACE Groundwater and Its Drought Potential in Taihang Mountain Region, China. J. Hydrol. 2022, 612, 128156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spearman, C. The Proof and Measurement of Association between Two Things. Am. J. Psychol. 1987, 100, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Chen, T.; Pan, Y.; Jiao, J.; Wu, Q.; Lv, Y.; Jiang, W. Spatiotemporal Variability of Terrestrial Water Storage over the Tibetan Plateau from the Joint Inversion of GNSS and GRACE Observations. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 27168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Fu, C.; Xu, Z.; Ding, A. Global Warming Intensifies Extreme Day-to-Day Temperature Changes in Mid–Low Latitudes. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2026, 16, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Luo, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ji, J.; Lai, B. Coupling Coordination and Driving Mechanism between Tourism Development, Ecological Conservation and Digital Economy: Insights from Chinese 278 Cities. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 37445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Q.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, S.; Chen, Q.; Fan, H.; Cao, C.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Luo, J.; Yao, Y. Groundwater Quality Evolution across China. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mo, S.; Schumacher, M.; Van Dijk, A.I.J.M.; Shi, X.; Wu, J.; Forootan, E. Near-Real-Time Monitoring of Global Terrestrial Water Storage Anomalies and Hydrological Droughts. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2025, 52, e2024GL112677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Lian, Y.; Sun, Y.; Zhou, H.; Luo, Z. Assessment of the Added Value of the GOCE GPS Data on the GRACE Monthly Gravity Field Solutions. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Lin, L.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, J. Temporal Downscaling Meteorological Variables to Unseen Moments: Continuous Temporal Downscaling via Multi-Source Spatial–Temporal-Wavelet Feature Fusion and Time-Continuous Manifold. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2025, 230, 32–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viviers, C.; Der Laan, M.V.; Gaffoor, Z.; Dippenaar, M. Downscaling and Validating GLDAS Groundwater Storage Anomalies by Integrating Precipitation for Recharge and Actual Evapotranspiration for Discharge. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2024, 54, 101879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swenson, S.; Chambers, D.; Wahr, J. Estimating Geocenter Variations from a Combination of GRACE and Ocean Model Output. J. Geophys. Res. 2008, 113, B08410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard Peltier, W.; Argus, D.F.; Drummond, R. Comment on “An Assessment of the ICE-6G_C (VM5a) Glacial Isostatic Adjustment Model” by Purcell et al. JGR Solid Earth 2018, 123, 2019–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ditmar, P. Conversion of Time-Varying Stokes Coefficients into Mass Anomalies at the Earth’s Surface Considering the Earth’s Oblateness. J. Geod. 2018, 92, 1401–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Ran, J.; Luan, Y.; Khorrami, B.; Xiao, Y.; Tangdamrongsub, N. The GWR Model-Based Regional Downscaling of GRACE/GRACE-FO Derived Groundwater Storage to Investigate Local-Scale Variations in the North China Plain. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 908, 168239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Bao, L.; Yao, G.; Wang, F.; Guo, Q.; Zhu, J.; Zhu, J.; Wang, Z.; Bi, J.; Zhu, C.; et al. The Analysis on Groundwater Storage Variations from GRACE/GRACE-FO in Recent 20 Years Driven by Influencing Factors and Prediction in Shandong Province, China. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 5819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, J.; Chen, Y.; Wang, S.; Chen, X.; Cheng, H.; Tian, X.; Wang, X.; Tan, K. Spatiotemporal Monitoring of Water Storage in the North China Plain from 2002 to 2022 Based on an Improved Grace Downscaling Method. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2025, 59, 102370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanlon, B.R.; Zhang, Z.; Save, H.; Wiese, D.N.; Landerer, F.W.; Long, D.; Longuevergne, L.; Chen, J. Global Evaluation of New GRACE Mascon Products for Hydrologic Applications. Water Resour. Res. 2016, 52, 9412–9429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Zhong, M.; Lemoine, J.; Biancale, R.; Hsu, H.; Xia, J. Evaluation of Groundwater Depletion in North China Using the Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) Data and Ground-based Measurements. Water Resour. Res. 2013, 49, 2110–2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellazzi, P.; Martel, R.; Galloway, D.L.; Longuevergne, L.; Rivera, A. Assessing Groundwater Depletion and Dynamics Using GRACE and InSAR: Potential and Limitations. Groundwater 2016, 54, 768–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Zhong, M.; Feng, W.; Zhang, Z.; Shen, Y.; Wu, D. Groundwater Depletion in the West Liaohe River Basin, China and Its Implications Revealed by GRACE and In Situ Measurements. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werth, S.; Manoochehr, S.; Grace, C.; Manuela, G.; Nitheshnirmal, S. Unlocking Insight: Past, Present, and Future of Groundwater Storage Change Digital Twins via GRACE and InSAR Integration. GRACE/GRACE-FO Sci. Team Meet. 2024, 10, GSTM2024-42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbaniaghdam, M.; Khozeymehnezhad, H.; Bilondi, M.P.; Ghasemie, H. Application of Modified Two-Point Hedging Policy in Groundwater Resources Planning in the Kashan Plain Aquifer. J. Groundw. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subirats, J.; Pastor-López, E.J.; Pascó, J.; Mendoza, M.; Guivernau, M.; Fernández, B.; Trobajo, R.; Viñas, M.; Biel, C.; Sánchez, D.; et al. Green Solutions for Treating Groundwater Polluted with Nitrates, Pesticides, Antibiotics, and Antibiotic Resistance Genes for Drinking Water Production. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 375, 124263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, D.; Xu, Y.; Cui, Y.; Cui, Y.; Butler, J.J.; Dong, L.; Wang, L.; Liu, D.; Wada, Y.; Hu, L.; et al. Unprecedented Large-Scale Aquifer Recovery through Human Intervention. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 7296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karandish, F.; Liu, S.; De Graaf, I. Global Groundwater Sustainability: A Critical Review of Strategies and Future Pathways. J. Hydrol. 2025, 657, 133060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Slope | Factors | Partitioning | Contribution Rate (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slope | Slope | ac | cc | ||

| >0 | ac & cc | >0 | >0 | ||

| ac | <0 | >0 | 100 | 0 | |

| cc | >0 | <0 | 0 | 100 | |

| <0 | ac & cc | <0 | <0 | / | / |

| ac | >0 | <0 | 100 | 0 | |

| cc | <0 | >0 | 0 | 100 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bi, Y.; Tan, X. Temporal and Spatial Variation Pattern of Groundwater Storage and Response to Environmental Changes in Shandong Province. Water 2026, 18, 189. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020189

Bi Y, Tan X. Temporal and Spatial Variation Pattern of Groundwater Storage and Response to Environmental Changes in Shandong Province. Water. 2026; 18(2):189. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020189

Chicago/Turabian StyleBi, Yanyang, and Xiucui Tan. 2026. "Temporal and Spatial Variation Pattern of Groundwater Storage and Response to Environmental Changes in Shandong Province" Water 18, no. 2: 189. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020189

APA StyleBi, Y., & Tan, X. (2026). Temporal and Spatial Variation Pattern of Groundwater Storage and Response to Environmental Changes in Shandong Province. Water, 18(2), 189. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020189