Quantifying Spatiotemporal Groundwater Storage Variations in China (2003–2019) Using Multi-Source Data

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

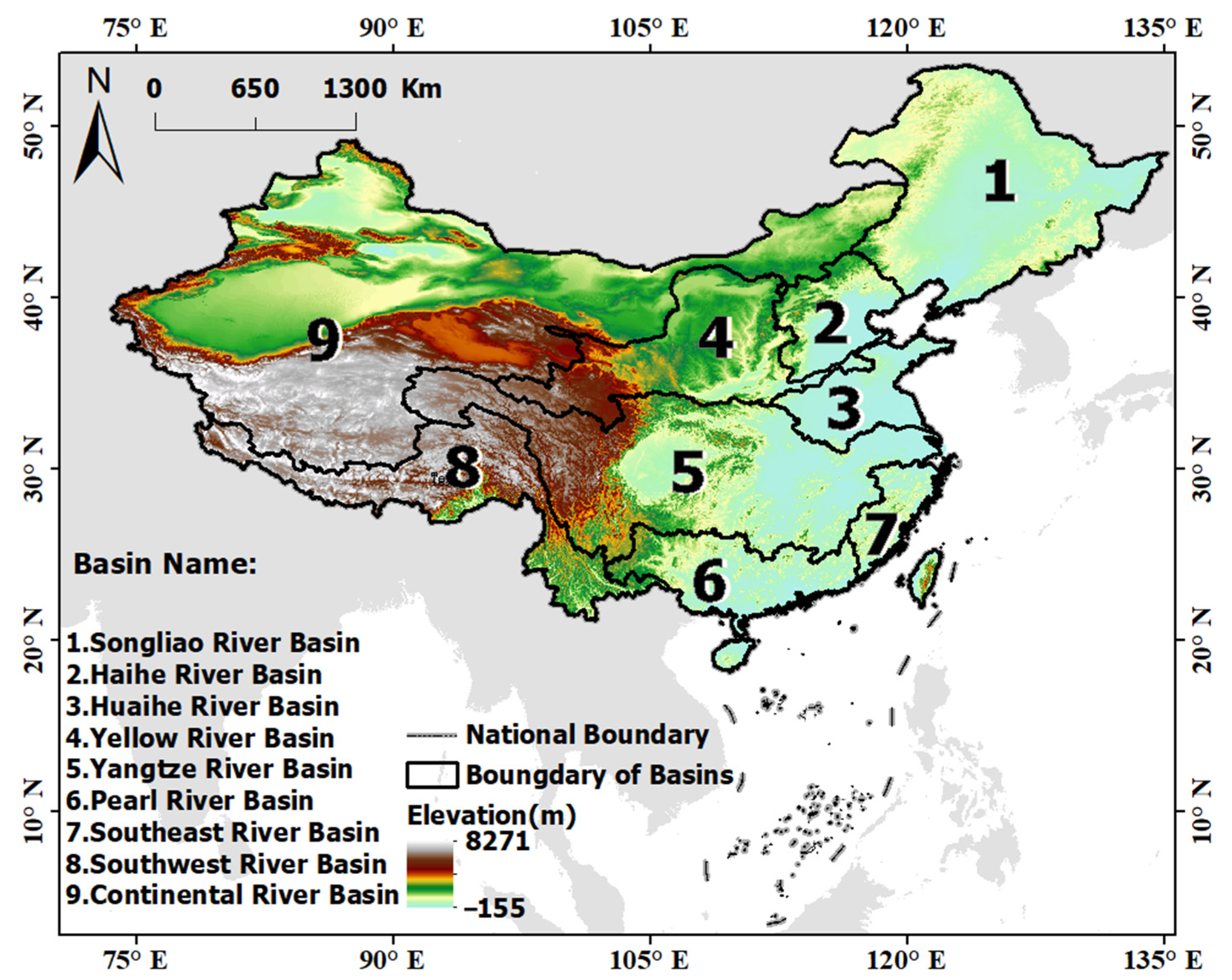

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data and Processing

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Groundwater Storage Estimation

2.3.2. Evaluation Metrics

2.3.3. Trend Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Comparison of GRACE-Derived GWSA with Water Resources Bulletin Data

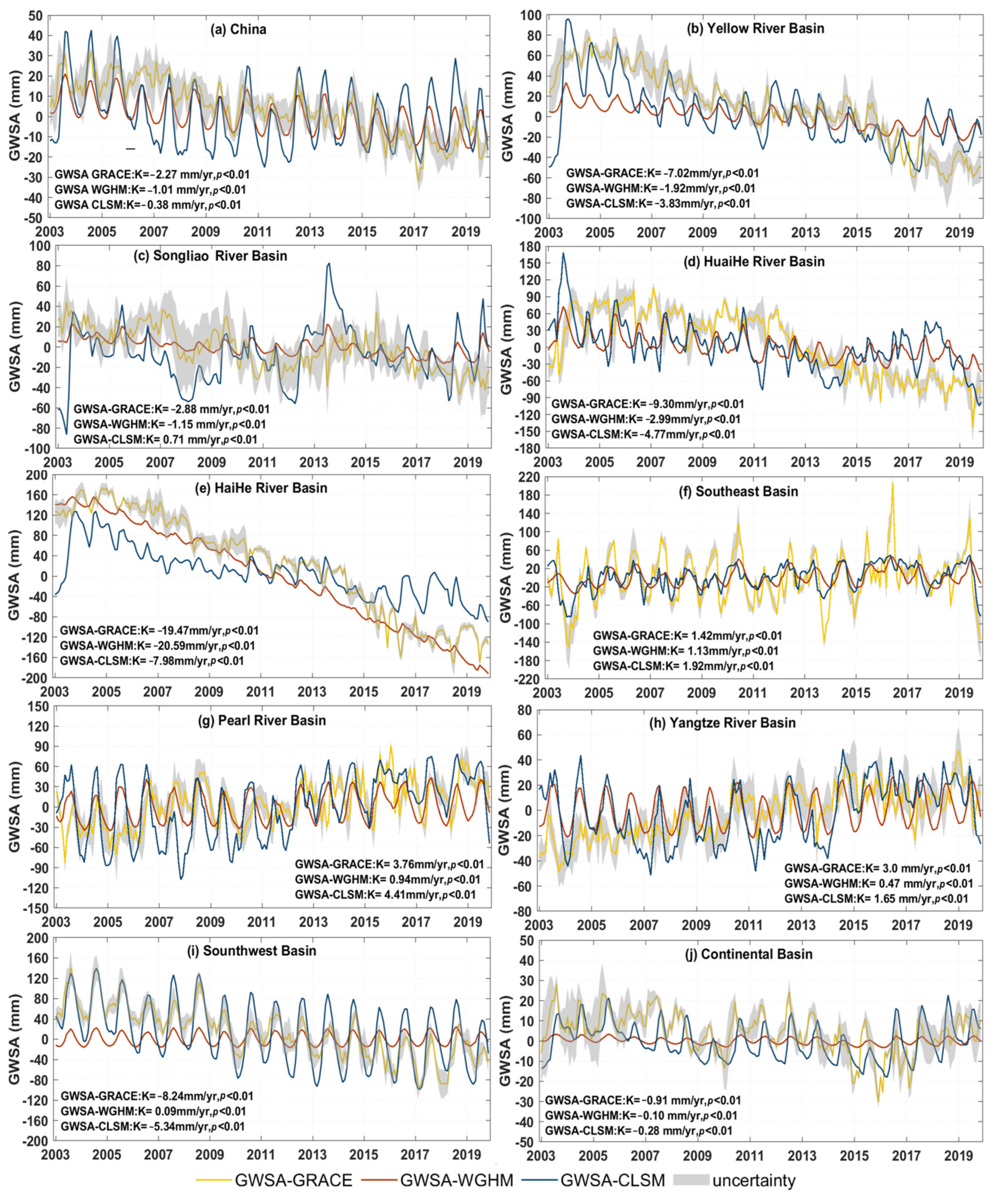

3.2. Evaluation of GWSA Across China

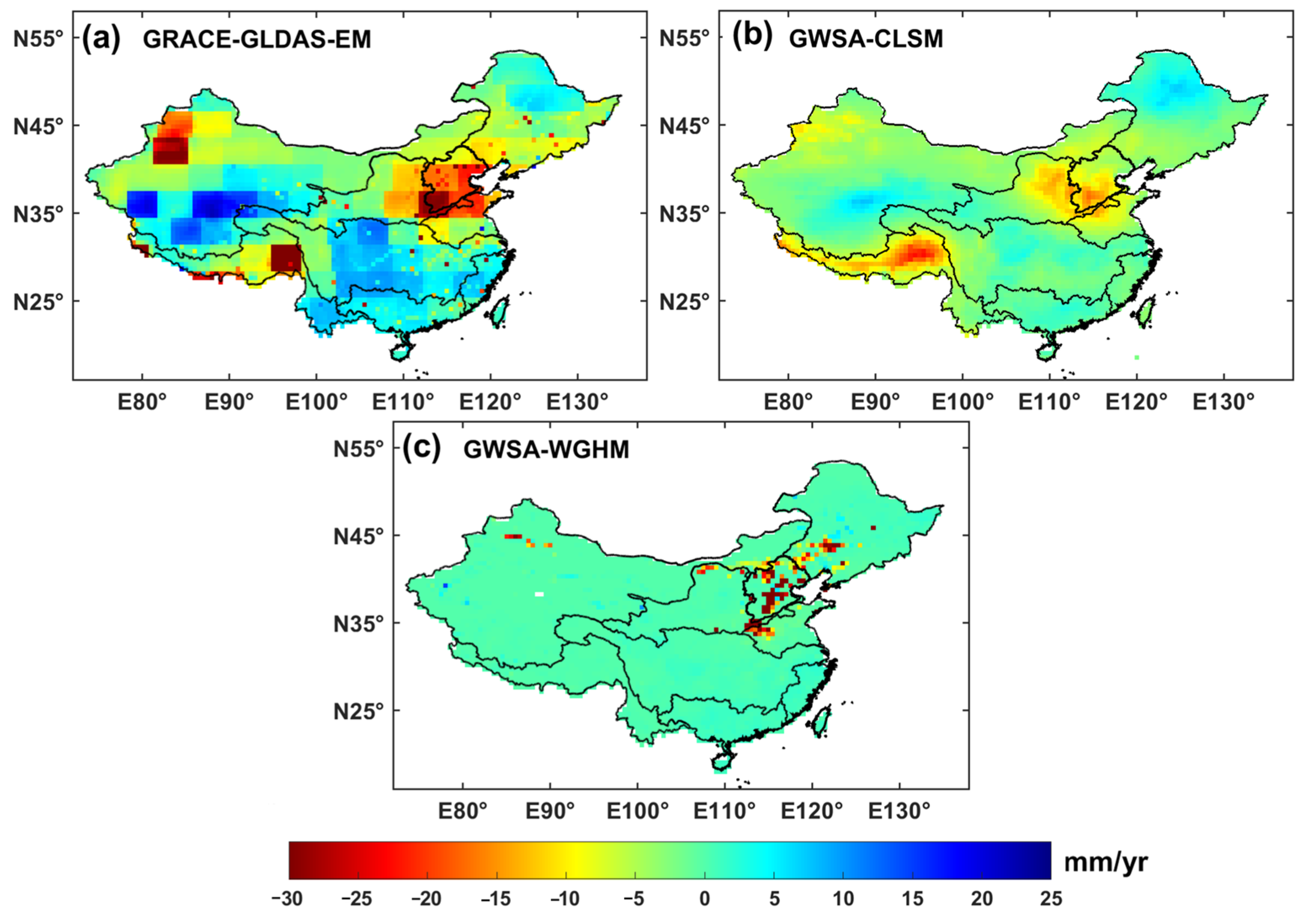

3.3. Comparison of Different GLDAS Models

4. Discussion

4.1. GWSA from Multi-Source Datasets

4.2. Evaluating GWSA in Basins and Comparison with Previous Work

| Basins | Source | Data | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Haihe River basin | Yin et al. [3] | GRACE CSR/JPL/GFZ RL06 mascon; GLDAS NOAH v2.1 | −9.15 mm/yr (2002–2017) |

| Zhao et al. [55] | GRACE CSR/JPL RL05 mascon; GSFC RL05 Mascon; GLDAS NOAH/ VIC/Mosaic/CLM | −1.7 ± 0.1 cm/yr (NCP, 2004–2016); −3.8 ± 0.1 cm/yr (mid-2013–mid-2016) | |

| Yang et al. [11] | GRACE CSR/JPL RL06 mascon; GLDAS NOAH/VIC/CLSM | 21.7 ± 0.7~−31.3 ± 1.0 mm/yr (Hebei Plain and Lower Yellow River Plain, 2002–2016) | |

| Huaihe River basin | Yin et al. [3] | GRACE CSR/JPL/GFZ RL06 mascon; GLDAS NOAH v3.3 | −1.80 mm/yr (HHRB, 2002–2017) |

| Su et al. [57] | GRACE JPL mascon RL06; GLDAS LSMs and WGHM | −1.14 ±0.89 cm/yr (Huang-Huai Plain, 2003–2015); −2.33 ± 0.18 cm/yr (HRB, 2003–2015) | |

| Wang et al. [30] | GRACE CSR RL06 mascon; GLDAS NOAH v2.1 | −0.5 cm/yr (HHRB, 2003 to 2021) | |

| Yellow River basin | Xie et al. [28] | GRACE CSR/JPL/GSFC mascon; GLDAS NOAH v2.1 | −4.2 ± 1.0 mm/yr (YRB, 2003–2015) |

| Zhang et al. [29] | GRACE CSR/JPL/GFZ RL05 mascon; GLDAS VIC | −3.11 mm/yr (YRB, 2005–2013) | |

| Liu et al. [64] | GRACE CSR/JPL/GFZ RL06 mascon; GLDAS NOAH v2.1 | −3.3 mm/a (YRB, 2003–2022) | |

| Yin et al. [3] | GRACE CSR/JPL/GFZ mascon RL06; GLDAS NOAH v2.1 | −4.90 mm/yr (YRB, 2002–2017) | |

| Huo et al. [58] | GLDAS NOAH v2.1 | −3.89 cm/yr (The Loess area, 2002–2014) | |

| Continental basin | Yin et al. [3] | GRACE CSR/JPL/GFZ RL06 mascon; GLDAS NOAH v2.1 | −3.28 mm/yr (CB, 2002–2017) |

| Yang et al. [11] | GRACE CSR/JPL RL06 mascon; GLDAS NOAH/VIC/CLSM | −0.7 ± 0.2~–9.4 ± 0.3 mm/yr (Tarim basin); 3.0 ±0.2 mm/yr (Lower Yellow River, 2005–2016) | |

| Yangtze River basin | Ferreira et al. [32] | GRACE CSR SH RL06; GLDAS NOAH v2.1; WGHM v2.2d | 1.76 mm/yr (YZB, 2003–2016) |

| Yang et al. [11] | GRACE CSR/JPL RL06 mascon; GLDAS NOAH/VIC/CLSM | 0.8 ± 0.5~8.4 ± 0.6 mm/yr (the middle and upper reaches of the Yangtze River, 2005–2016) | |

| Songliao River basin | Zhong et al. [62] | GRACE CSR mascon; GLDAS NOAH/VIC/Mosaic/CLM | −0.68 ± 0.36 cm/yr (WLRB; 2005–2011); −0.32 ± 0.18 cm/yr (2005–2015) |

| Chen et al. [63] | GRACE CSR/JPL/GFZ RL05 mascon/SH; GLDAS NOAH/VIC/Mosaic/CLM | −1.04 ± 0.59 mm/yr (Songhua River Basin, 1982–1994); 3.91 ± 1.06 mm/yr (1998–2008); −5.51 ± 3.46 mm/yr (2009–2013). | |

| Yin et al. [3] | GRACE CSR/JPL/GFZ RL06 mascon; GLDAS NOAH v2.1 | −1.75 mm/yr (Songhua River Basin); −5.81 mm/yr (Liaohe River Basin, 2002–2017) | |

| Yang et al. [11] | GRACE CSR/JPL RL06 mascon; GLDAS NOAH/VIC/CLSM | 2.8 ± 0.6 mm/yr (Songnen Plain); −5.6 ± 0.5 mm/yr (Western Liaohe River Plain, 2005–2016) |

4.3. Uncertainty and Future Improvements

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Siebert, S.; Burke, J.; Faures, J.M.; Frenken, K.; Hoogeveen, J.; Döll, P.; Portmann, F.T. Groundwater use for irrigation—A global inventory. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2010, 14, 1863–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S. Hydrogeochemical Evaluation and Groundwater Quality; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Xu, Y.; Zhu, X.; Zhao, J.; Yang, Y.; Li, J. Variations of groundwater storage in different basins of China over recent decades. J. Hydrol. 2021, 598, 126282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, Y.; van Beek, L.P.H.; van Kempen, C.M.; Reckman, J.W.T.M.; Vasak, S.; Bierkens, M.F.P. Global depletion of groundwater resources. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2010, 37, L20402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, D.; Chen, X.; Scanlon, B.R.; Wada, Y.; Hong, Y.; Singh, V.P.; Chen, Y.; Wang, C.; Han, Z.; Yang, W. Have GRACE satellites overestimated groundwater depletion in the Northwest India Aquifer? Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 24398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanlon, B.R.; Longuevergne, L.; Long, D. Ground referencing GRACE satellite estimates of groundwater storage changes in the California Central Valley, USA. Water Resour. Res. 2012, 48, W04520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Famiglietti, J.S.; Lo, M.; Ho, S.L.; Bethune, J.; Anderson, K.J.; Syed, T.H.; Swenson, S.C.; de Linage, C.R.; Rodell, M. Satellites measure recent rates of groundwater depletion in California’s Central Valley. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2011, 38, L03403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.W.; Famiglietti, J.S.; Purdy, A.J.; Adams, K.H.; McEvoy, A.L.; Reager, J.T.; Bindlish, R.; Wiese, D.N.; David, C.H.; Rodell, M. Groundwater depletion in California’s Central Valley accelerates during megadrought. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 7825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, W.; Zhong, M.; Lemoine, J.M.; Biancale, R.; Hsu, H.T.; Xia, J. Evaluation of groundwater depletion in North China using the Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) data and ground-based measurements. Water Resour. Res. 2013, 49, 2110–2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaudry, N.; Sun, Y.; Afolabi, O.O.D. Exploiting constructed wetlands for industrial effluent phytodesalination in Jing-Jin-Ji urban agglomeration, China. Int. J. Phytoremediation 2023, 25, 851–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, C.; Gong, H.; Xu, L.; Huang, Z.; Lu, S. Comparison of groundwater storage changes over losing and gaining aquifers of China using GRACE satellites, modeling and in-situ observations. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 938, 173514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Shum, C.K.; Zhong, M.; Pan, Y. Groundwater Storage Changes in China from Satellite Gravity: An Overview. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, F.; Liang, B.; Yang, G.; Lu, Z.; Li, Z.; Fu, Y. Evaluation of groundwater storage variability and relationship with hydrometeorological factors in the Huang-Huai-Hai Plain, China, using GRACE and GLDAS Data (2002–2023). J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2025, 60, 102540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Yao, Y.; Ji, Q.; Jin, H.; Wang, T.; Lancia, M.; Meng, X.; Zheng, C.; Yang, D. Groundwater depletion intensified by irrigation and afforestation in the Yellow River Basin: A spatiotemporal analysis using GRACE and well monitoring data with implications for sustainable management. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2025, 59, 102324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, P.K.; Chandra, S.; Henry, P.K. Monitoring of the Groundwater Level using GRACE with GLDAS Satellite Data in Ganga Plain, India to Understand the Challenges of Groundwater, Depletion, Problems, and Strategies for Mitigation. Environ. Chall. 2024, 15, 100874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapley, B.D.; Bettadpur, S.; Watkins, M.; Reigber, C. The gravity recovery and climate experiment: Mission overview and early results. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2004, 31, L09607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Famiglietti, J.S.; Scanlon, B.R.; Rodell, M. Groundwater Storage Changes: Present Status from GRACE Observations. Surv. Geophys. 2016, 37, 397–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodell, M.; Chen, J.; Kato, H.; Famiglietti, J.S.; Nigro, J.; Wilson, C.R. Estimating groundwater storage changes in the Mississippi River basin (USA) using GRACE. Hydrogeol. J. 2006, 15, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, W.; Zhang, P.; Chen, P.; Li, J.; Gao, Y. Spatiotemporal Variations and Sustainability Characteristics of Groundwater Storage in North China from 2002 to 2022 Revealed by GRACE/GRACE Follow-On and Multiple Hydrologic Data. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Gong, H.; Chen, B.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Z. Long-term and seasonal variation in groundwater storage in the North China Plain based on GRACE. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2021, 104, 102560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, W.; Gao, Y.; Qian, H.; Ma, Y.; Su, Z.; Ma, W.; Liu, Y.; Xu, P. Spatiotemporal Variation Characteristics of Groundwater Storage and Its Driving Factors and Ecological Effects in Tibetan Plateau. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Jia, B.; Yuan, X.; Xie, Z.; Yang, K.; Shi, J. The slowdown of increasing groundwater storage in response to climate warming in the Tibetan Plateau. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2024, 7, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Li, W.; Zheng, Y.J.; Li, L.; Wang, X. Research on the Disparity and Influencing Factors of Water Resources Distribution in China. 2025. Available online: https://zgstbckx.xml-journal.net/en/article/doi/10.16843/j.sswc.2025213 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Zhao, X.B.; Zhong, H.P.; Huang, C.S. Existed Problems and Countermeasures for Development and Utilization of Groundwater in South China. Ground Water 2008, 30, 40–43. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.; Nie, Z.; Cui, H.; Wang, Q.; Yan, M.; Tian, Y.; Wang, J. Main causes and mechanism for the natural oasis degeneration in the lower reaches of northwest inland basins. Hydrogeol. Eng. Geol. 2022, 49, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Sun, C.; Jiang, Q.; Liu, C.; Shan, J. Analysis of spatiotemporal variation characteristics of groundwater storage and their influencing factors in three provinces of Northeast China. Adv. Water Sci. 2023, 34, 360–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, D.; Yang, W.; Scanlon, B.R.; Zhao, J.; Liu, D.; Burek, P.; Pan, Y.; You, L.; Wada, Y. South-to-North Water Diversion stabilizing Beijing’s groundwater levels. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Xu, Y.-P.; Wang, Y.; Gu, H.; Wang, F.; Pan, S. Influences of climatic variability and human activities on terrestrial water storage variations across the Yellow River basin in the recent decade. J. Hydrol. 2019, 579, 124218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Xie, X.; Zhu, B.; Meng, S.; Yao, Y. Unexpected groundwater recovery with decreasing agricultural irrigation in the Yellow River Basin. Agric. Water Manag. 2019, 213, 858–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Li, Y.; Li, C.; Lai, Y.; Yang, C. Variations in groundwater storage in the Huang-Huai-Hai region and attribution analysis based on GRACE data. Hydro-Science and Engineering. Hydro-Sci. Eng. 2023, 6, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, X.; Zhang, S.; Chen, M.; Li, M.; Wang, Y. Spatiotemporal variation analysis of groundwater storage in the southeastern mountainous region of China based on GRACE data. Geod. Geodyn. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, V.G.; Yong, B.; Tourian, M.J.; Ndehedehe, C.E.; Shen, Z.; Seitz, K.; Dannouf, R. Characterization of the hydro-geological regime of Yangtze River basin using remotely-sensed and modeled products. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 718, 137354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Yang, Y.; Cao, J.; Xia, R.; Wang, Z.; Luan, S.; Lin, Y. Groundwater resources evaluation and problem analysis in Pearl River Basin. Geol. China 2021, 48, 1020–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Yeh, P.J.F.; Pan, Y.; Jiao, J.J.; Gong, H.; Li, X.; Güntner, A.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zheng, L. Detection of large-scale groundwater storage variability over the karstic regions in Southwest China. J. Hydrol. 2019, 569, 409–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Z.; Dong, J.; Chang, L.; Li, C.; Zhang, P.; Gu, X.; Nie, Z. Groundwater circulation patterns and its resources assessment of inland river catchments in northwestern China. Geol. China 2021, 48, 1094–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Save, H.; Bettadpur, S.; Tapley, B.D. High-resolution CSR GRACE RL05 mascons. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2016, 121, 7547–7569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanlon, B.R.; Zhang, Z.; Save, H.; Wiese, D.N.; Landerer, F.W.; Long, D.; Longuevergne, L.; Chen, J. Global evaluation of new GRACE mascon products for hydrologic applications. Water Resour. Res. 2016, 52, 9412–9429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, M.M.; Wiese, D.N.; Yuan, D.N.; Boening, C.; Landerer, F.W. Improved methods for observing Earth’s time variable mass distribution with GRACE using spherical cap mascons. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2015, 120, 2648–2671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chen, X.; Hu, Q.; Liu, J. Responses of terrestrial water storage to climate variation in the Tibetan Plateau. J. Hydrol. 2020, 584, 124652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, S.; Sneeuw, N. Filling the Data Gaps Within GRACE Missions Using Singular Spectrum Analysis. J. Geophys. Res.-Solid Earth 2021, 126, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodell, M.; Houser, P.R.; Jambor, U.; Gottschalck, J.; Mitchell, K.; Meng, C.J.; Arsenault, K.; Cosgrove, B.; Radakovich, J.; Bosilovich, M.; et al. The Global Land Data Assimilation System. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2004, 85, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Döll, P.; Müller Schmied, H.; Schuh, C.; Portmann, F.T.; Eicker, A. Global-scale assessment of groundwater depletion and related groundwater abstractions: Combining hydrological modeling with information from well observations and GRACE satellites. Water Resour. Res. 2014, 50, 5698–5720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doll, A.a.; Henrichs, T.; Kaspar, F.; Lehner, B.; RÖSch, T.; Siebert, S. Development and testing of the WaterGAP 2 global model of water use and availability. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2003, 48, 317–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, J.; Miao, C.; Xu, Z.; Duan, Q. Parameter uncertainty analysis for large-scale hydrological model: Challenges and comprehensive study framework. Adv. Water Sci. 2022, 33, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhang, L.; Li, Y. Research progress on uncertainty quantification and constraint methods for climate and hydrological projections. Clim. Change Res. 2025, 21, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rateb, A.; Scanlon, B.R.; Pool, D.R.; Sun, A.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, J.; Clark, B.; Faunt, C.C.; Haugh, C.J.; Hill, M.; et al. Comparison of Groundwater Storage Changes from GRACE Satellites with Monitoring and Modeling of Major U.S. Aquifers. Water Resour. Res. 2020, 56, e2020WR027556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Feng, G. Large-scale variations of global groundwater from satellite gravimetry and hydrological models, 2002–2012. Glob. Planet. Change 2013, 106, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; She, D.; Li, M.; Wang, T. Using Satellite Observations to Assess Applicability of GLDAS and WGHM Hydrological Mode. Geomat. Inf. Sci. Wuhan Univ. 2019, 44, 1596–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, A.; Gleeson, T.; Rosolem, R.; Pianosi, F.; Wada, Y.; Wagener, T. A large-scale simulation model to assess karstic groundwater recharge over Europe and the Mediterranean. Geosci. Model Dev. 2015, 8, 1729–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, G.; Zheng, C.; Scanlon, B.R.; Liu, J.; Li, W. Use of flow modeling to assess sustainability of groundwater resources in the North China Plain. Water Resour. Res. 2013, 49, 159–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koster, R.D.; Suarez, M.J.; Ducharne, A.; Stieglitz, M.; Kumar, P. A catchment-based approach to modeling land surface processes in a general circulation model: 1. Model structure. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2000, 105, 24809–24822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Rodell, M.; Kumar, S.; Beaudoing, H.K.; Getirana, A.; Zaitchik, B.F.; de Goncalves, L.G.; Cossetin, C.; Bhanja, S.; Mukherjee, A.; et al. Global GRACE Data Assimilation for Groundwater and Drought Monitoring: Advances and Challenges. Water Resour. Res. 2019, 55, 7564–7586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, F.; Zhang, L.; Ou, T.; Chen, D.; Yao, T.; Tong, K.; Qi, Y. Hydrological response to future climate changes for the major upstream river basins in the Tibetan Plateau. Glob. Planet. Change 2016, 136, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Painter, S.L.; Moulton, J.D.; Wilson, C.J. Modeling challenges for predicting hydrologic response to degrading permafrost. Hydrogeol. J. 2013, 21, 221–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Zhang, B.; Yao, Y.; Wu, W.; Meng, G.; Chen, Q. Geodetic and hydrological measurements reveal the recent acceleration of groundwater depletion in North China Plain. J. Hydrol. 2019, 575, 1065–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Pan, Y.; Gong, H.; Yeh, P.J.F.; Li, X.; Zhou, D.; Zhao, W. Subregional-scale groundwater depletion detected by GRACE for both shallow and deep aquifers in North China Plain. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2015, 42, 1791–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Guo, B.; Zhou, Z.; Zhong, Y.; Min, L. Spatio-Temporal Variations in Groundwater Revealed by GRACE and Its Driving Factors in the Huang-Huai-Hai Plain, China. Sensors 2020, 20, 922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, A.; Peng, J.; Chen, X.; Deng, L.; Wang, G.; Cheng, Y. Groundwater storage and depletion trends in the Loess areas of China. Environ. Earth Sci. 2016, 75, 1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, J.; Zhang, X.; Chen, Q. Spatio-temporal terrestrial water storage changes in the Hexi Corridor derived by GRACE/GRACE-FO gravity satellites over the past 20 years. Prog. Geophys. 2024, 39, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Ferreira, V.G.; Chen, J. Monitoring groundwater changes in the Yangtze River basin using satellite and model data. Arab. J. Geosci. 2016, 9, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Li, W.; Wang, H.; Ming, D.; Han, L. Analysis of the groundwater storage variations and their driving factors in the three eastern coastal urban agglomerations of China. Remote Sens. Nat. Resour. 2022, 34, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Zhong, M.; Feng, W.; Zhang, Z.; Shen, Y.; Wu, D. Groundwater Depletion in the West Liaohe River Basin, China and Its Implications Revealed by GRACE and In Situ Measurements. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhang, W.; Nie, N.; Guo, Y. Long-term groundwater storage variations estimated in the Songhua River Basin by using GRACE products, land surface models, and in-situ observations. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 649, 372–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Zhou, M.; Shao, W. Spatio-Temporal Characteristics and Influencing Factors Analysis of Groundwater Storage Variations in the Yellow River Basin. Yellow River 2024, 7, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Cazenave, A.; Dahle, C.; Llovel, W.; Panet, I.; Pfeffer, J.; Moreira, L. Applications and Challenges of GRACE and GRACE Follow-On Satellite Gravimetry. Surv. Geophys. 2022, 43, 305–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Chen, X.; Qian, J. A Review on the Methodology of Scale Issues in Quantitative Remote Sensing. Geogr. Sci. 2019, 39, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellazzi, P.; Martel, R.; Rivera, A.; Huang, J.; Pavlic, G.; Calderhead, A.I.; Chaussard, E.; Garfias, J.; Salas, J. Groundwater depletion in Central Mexico: Use of GRACE and InSAR to support water resources management. Water Resour. Res. 2016, 52, 5985–6003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type | Product Name | Variables Used | Resolution, Coverage Period | Data Access |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Satellite Gravimetry | GRACE JPL mascon RL06 (level 3) | TWSA | 0.5° × 0.5°, monthly, 2003–2019 | http://isdc.gfz-potsdam.de/GRACE-isdc/ (accessed on 11 March 2024) |

| GLDAS | NOAH025_M_2.1 | SMS, SWE, CWS | 0.25° × 0.25°, monthly, 2003–2019 | https://search.earthdata.nasa.gov/ (accessed on 22 June 2024) |

| VIC10_M_2.1 | SMS, SWE, CWS | 1° × 1°, monthly, 2003–2019 | ||

| CLSM025_DA1_D_2.2 | SMS, SWE, CWS; GWS | 0.25° × 0.25°, daily, 2003–2019 | ||

| WGHM | WaterGAP_v2.2 | SWS, GWS | 0.5° × 0.5°, monthly, 2003–2019 | https://doi.pangaea.de/10.1594/PANGAEA.948461?format=html#download (accessed on 27 July 2025) |

| In situ data | China Water Resources Bulletin | GWRQ | yearly, 2005–2019 | http://www.mwr.gov.cn/sj/tjgb/szygb/ (accessed on 24 May 2024) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tu, L.; Sun, Z.; Zheng, Z.; Abowarda, A.S. Quantifying Spatiotemporal Groundwater Storage Variations in China (2003–2019) Using Multi-Source Data. Water 2026, 18, 151. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020151

Tu L, Sun Z, Zheng Z, Abowarda AS. Quantifying Spatiotemporal Groundwater Storage Variations in China (2003–2019) Using Multi-Source Data. Water. 2026; 18(2):151. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020151

Chicago/Turabian StyleTu, Lin, Zhangli Sun, Zhoutao Zheng, and Ahmed Samir Abowarda. 2026. "Quantifying Spatiotemporal Groundwater Storage Variations in China (2003–2019) Using Multi-Source Data" Water 18, no. 2: 151. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020151

APA StyleTu, L., Sun, Z., Zheng, Z., & Abowarda, A. S. (2026). Quantifying Spatiotemporal Groundwater Storage Variations in China (2003–2019) Using Multi-Source Data. Water, 18(2), 151. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020151