Assessment of Soil and Groundwater Contamination from Olive Mill Wastewater Disposal at Ben Aoun, Central Tunisia

Abstract

1. Introduction

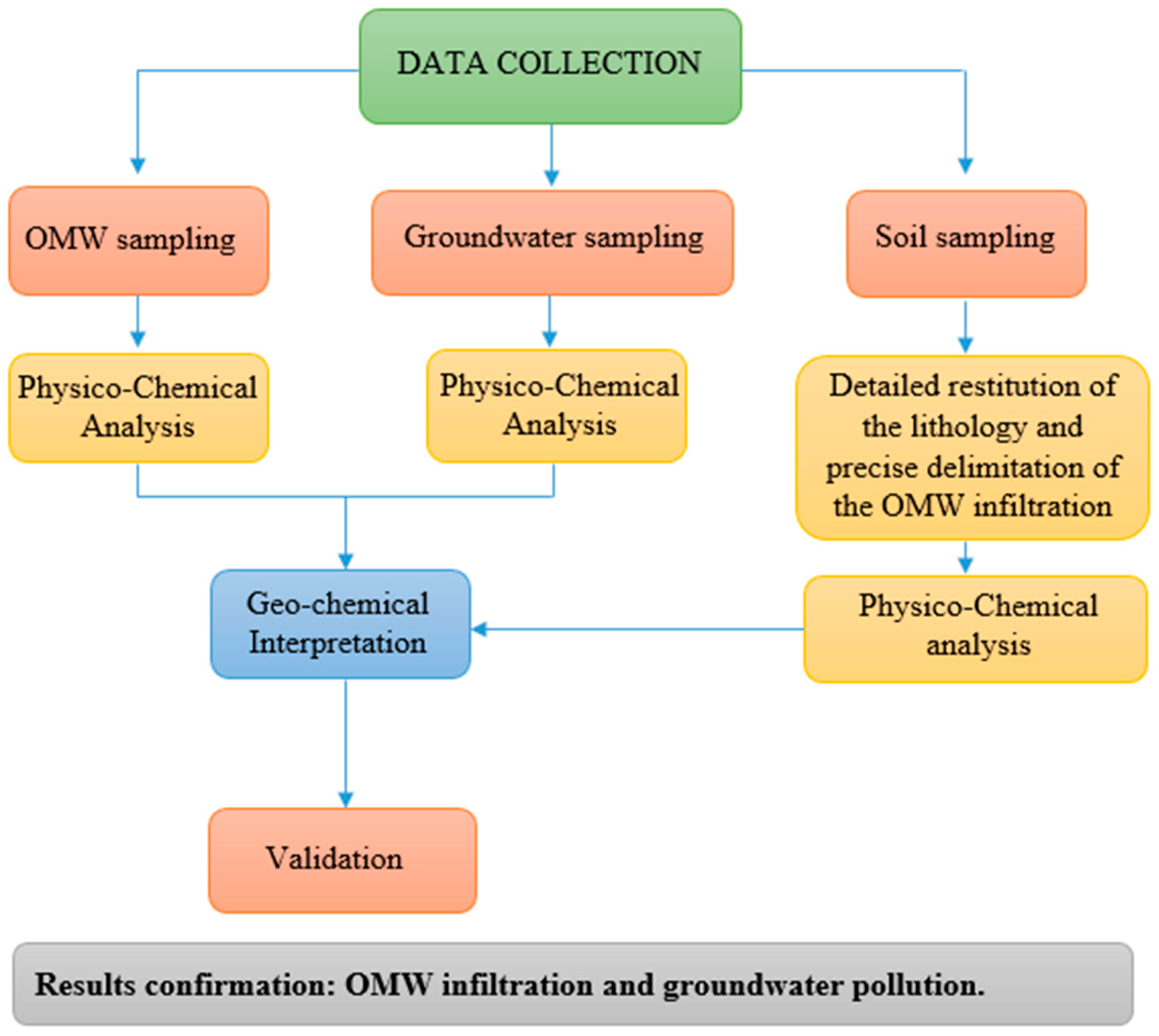

2. Characteristics of OMW and Management Practices

3. Materials and Methods

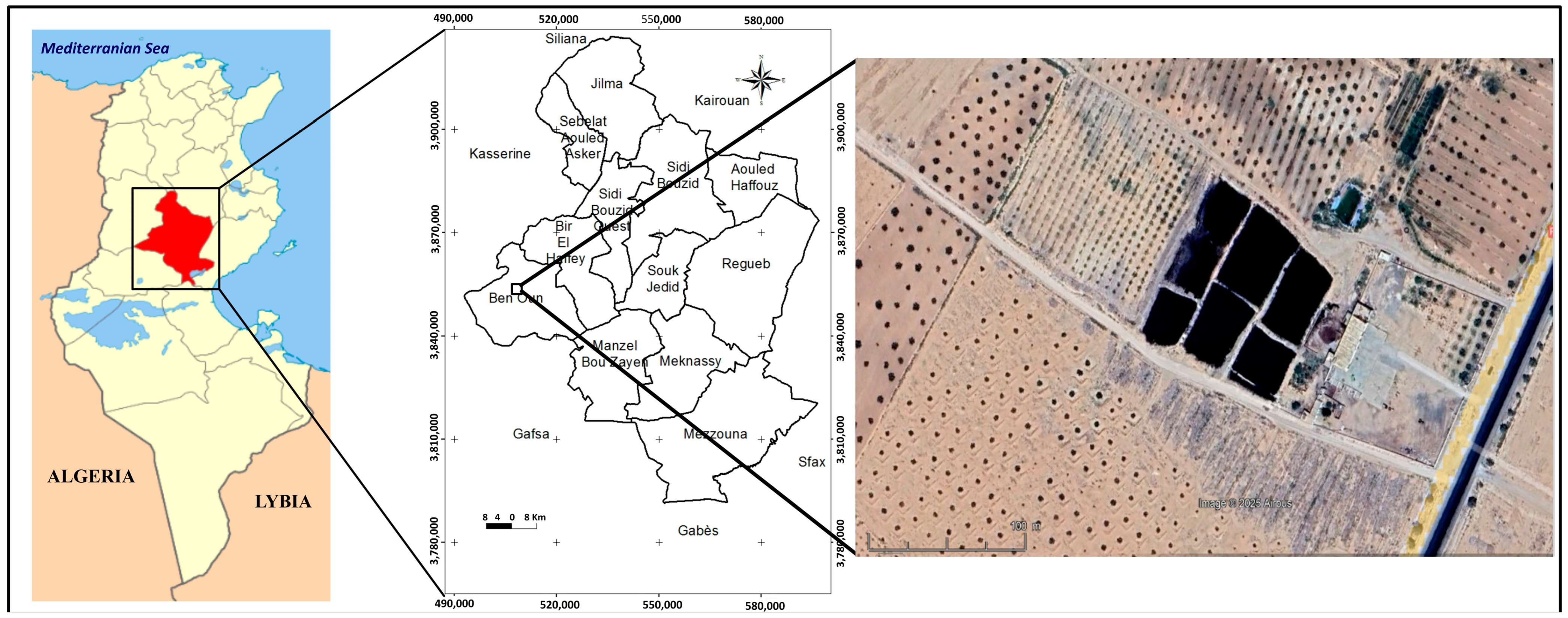

3.1. Study Area

3.1.1. Climate and Physiography

3.1.2. Geological and Hydrogeological Setting

3.1.3. The Ben Aoun Evaporation Pond

3.2. Sampling of OMW

- E1: collected from the surface of the eastern basin, which contains the oldest OMW residues;

- E2: a composite sample from both surface and bottom layers of the central basin, representing intermediate-aged OMW;

- E3: collected directly from the southern spillway, corresponding to the most recent discharge from the olive mill.

3.3. Analytical Methods for OMW Samples

3.3.1. Physicochemical Parameters

- pH and EC were measured in situ using a WTW Multi Line 3430 multiparameter meter, calibrated with standard solutions at 25 °C.

- Total solids (TS) were determined after drying at 105 °C for 24 h, while volatile solids (VS) and organic matter were measured by calcination at 550 °C for 2 h.

3.3.2. Chemical Oxygen Demand

3.3.3. Total Kjeldahl Nitrogen

3.3.4. Phenolic Compounds

3.3.5. Mineral Composition

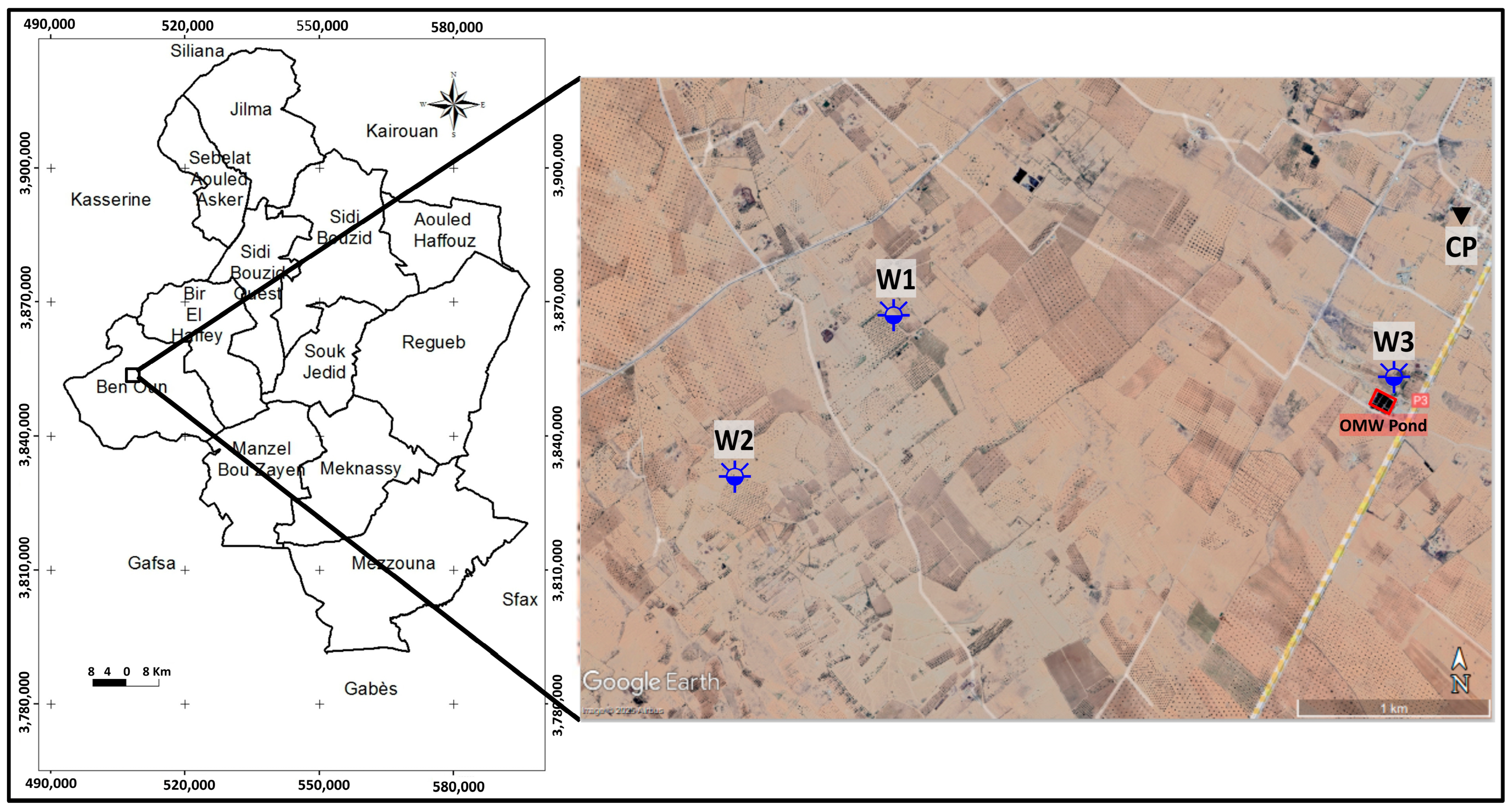

3.4. Groundwater Sampling and Analysis

- pH and EC, determined in situ with a multiparameter probe (WTW Multi Line 3430, WTW GmbH, Weilheim, Germany);

- Total phenolic compounds, analyzed using the Folin–Ciocalteu method as described above.

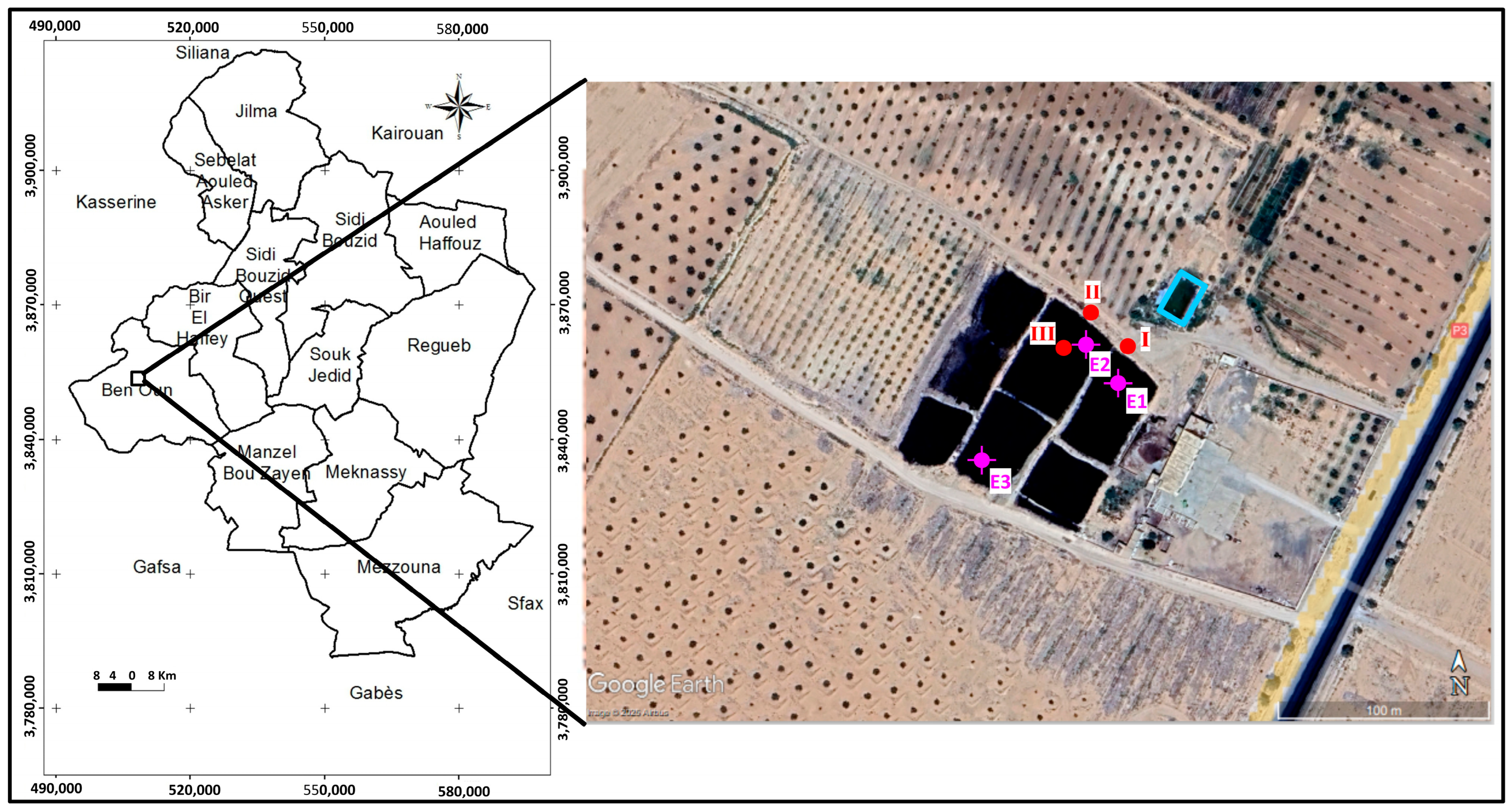

3.5. Borehole Drilling and Soil Sampling

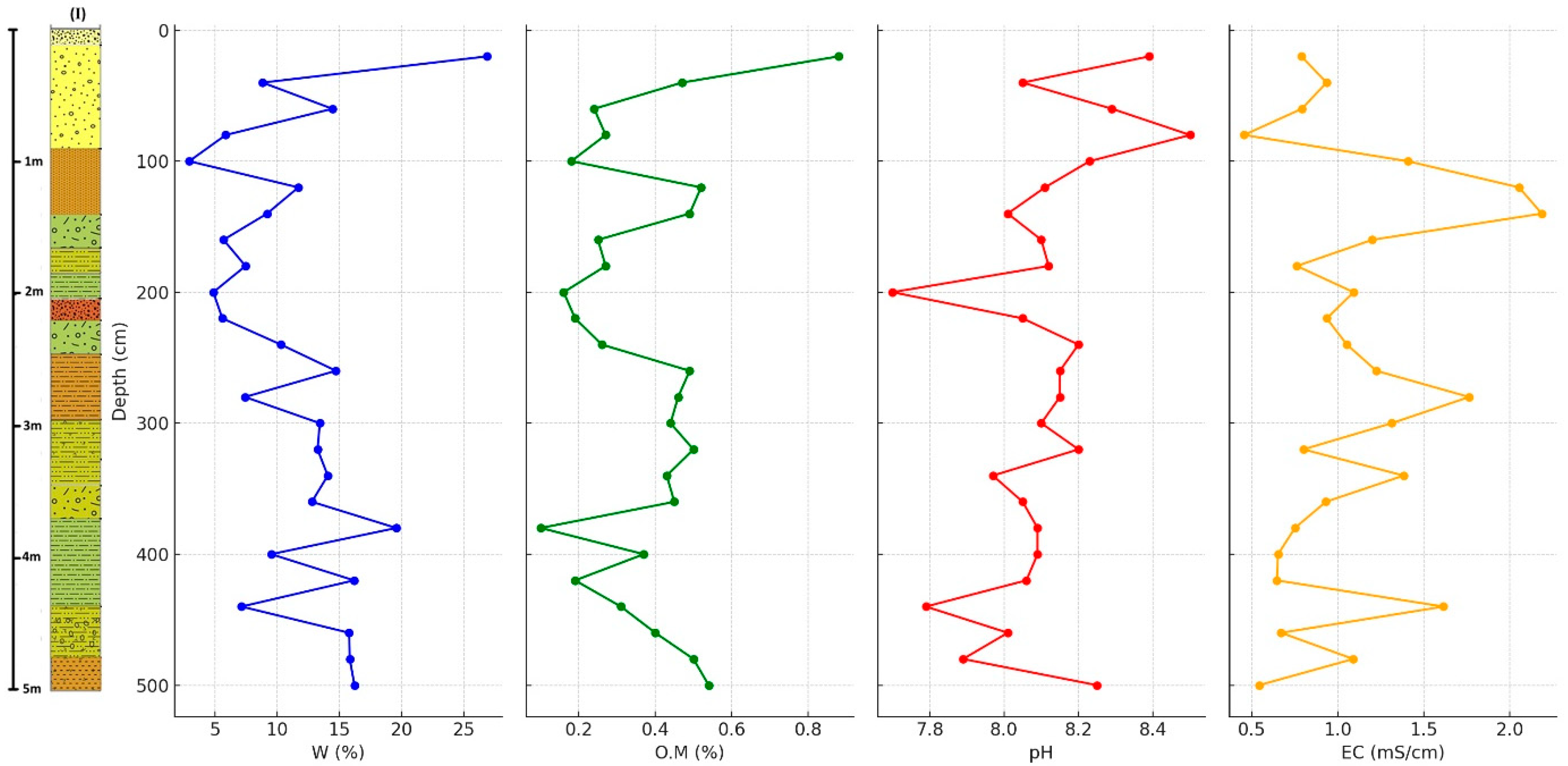

- Borehole I: outside and adjacent to the first basin,

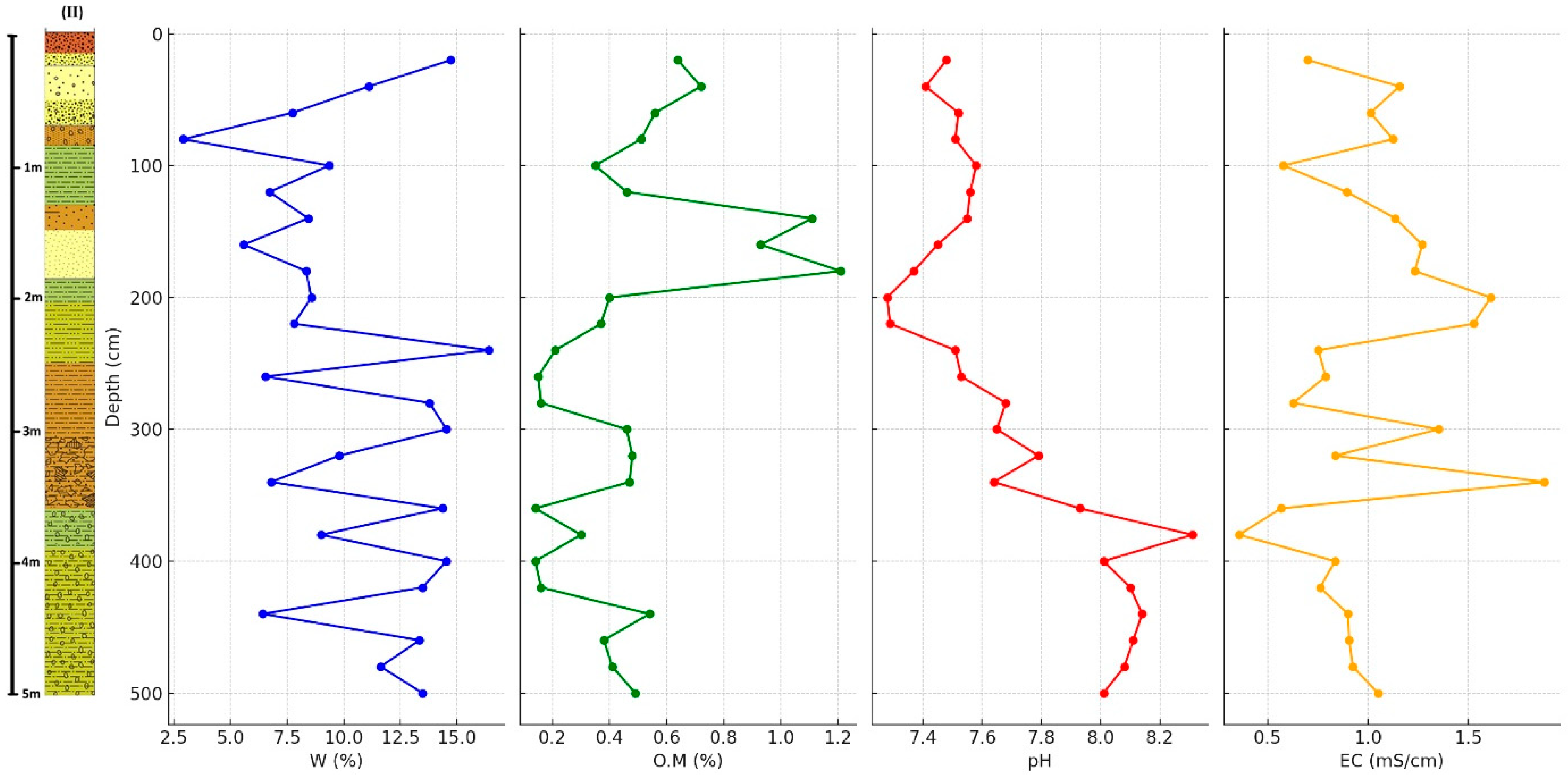

- Borehole II: outside and near the second basin,

- Borehole III: inside the second basin.

3.6. Soil Analysis

- pH and EC: measured in a 1:2.5 (w/v) soil–water suspension using calibrated electrodes.

- Organic matter determined by loss-on-ignition at 550 °C for 2 h.

- Total phenolic content: extracted using ethyl acetate (1:1 v/v) and analyzed via the Folin–Ciocalteu method.

3.7. Data Validation and Comparison

4. Results and Discussions

4.1. Physicochemical Characteristics of OMW

4.2. Soil Contamination

4.3. Groundwater Quality

4.4. Environmental Implications

5. Conclusions

6. Recommendations

- Containment and isolation of the pond through the installation of a low-permeability bottom liner and a perimeter slurry trench to prevent further seepage;

- Continuous environmental monitoring of soil and groundwater quality to detect and track contaminant migration;

- Implementation of pretreatment and valorization options, such as anaerobic digestion, evaporation-concentration, or composting, to reduce pollutant loads before discharge;

- Progressive replacement of open ponds with engineered evaporation basins or integrated treatment systems that combine physical, chemical, and biological processes.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Issaoui, W.; Aydi, A.; Mahmoudi, M.; Cilek, M.U.; Abichou, T. GIS based multi-criteria evaluation for olive mill wastewater disposal site selection. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2021, 23, 1490–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra, J.; Marti, E.; Montserrat, G.; Cruanas, R.; Garau, M.A. Characterisation and evolution of a soil affected by olive oil mill wastewater disposal. Sci. Total. Environ. 2001, 279, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cifuentes-Cabezas, M.; Carbonell-Alcaina, C.; Vincent-Vela, M.C.; Mendoza-Roca, J.A.; Álvarez-Blanco, S. Comparison of different ultrafiltration membranes as first step for the recovery of phenolic compounds from olive-oil washing wastewater. Process. Saf. Environ. Prot. 2021, 149, 724–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekki, A.; Dhouib, A.; Sayadi, S. Polyphenols dynamics and phytotoxicity in a soil amended by olive mill wastewaters. J. Environ. Manag. 2007, 84, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- S’Habou, R.; Zairi, M.; Ben Dhia, H. Characterisation and Environnemental Impacts of Olive Oil Wastewater Disposal. Environ. Technol. 2005, 26, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu-Dalo, M.A.; Al-Atoom, M.A.; Aljarrah, M.T.; Albiss, B.A. Preparation and Characterization of Polymer Membranes Impregnated with Carbon Nanotubes for Olive Mill Wastewater. Polymers 2022, 14, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdennbi, S.; Chaieb, M.; Mekki, A. Long-term effects of olive mill waste waters spreading on the soil rhizospheric properties of olive trees grown under Mediterranean arid climate. Soil. Res. 2023, 62, SR23102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roig, A.; Cayuela, M.L.; Sànchez-Monedero, M.A. An overview on olive mill wastes and their valorization methods. Waste Manag. 2006, 26, 960–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issaoui, W.; Hamdi, N.I.; Khaskhoussi, S.; Inoubli, M.H. Monitoring of soil contamination from olive mill wastewater (OMW) using physico-chemical, geotechnical analysis and electrical resistivity tomography (ERT) investigation. Environ. Earth Sci. 2023, 82, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seferou, P.; Soupios, P.; Kourgialas, N.N.; Dokou, Z.; Karatzas, G.P.; Candasayar, E.; Papadopoulos, N.; Dimitriou, V.; Sarris, A.; Sauter, M. Olive-oil mill wastewater transport under unsaturated and saturated laboratory conditions using the geoelectrical resistivity tomography method and the FEFLOW model. Hydrogeol. J. 2013, 21, 1219–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Alimentación y la Agricultura (FAO). Captación Y Almacenamiento DE Agua DE Lluvia. Opciones Técnicas PARA la agricultura Familiar en América Latina y el Caribe; Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Alimentación y la Agricultura (FAO): Santiago, Chile, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zaier, H.; Chmingui, W.; Rajhi, H.; Bouzidi, D.; Roussos, S.; Rhouma, A. Physico-chemical and microbiological characterization of olive mill wastewater (OMW) of different regions of Tunisia (North, Sahel, South). J. New Sci. 2017, 48, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Kissi, M.; Mountadar, M.; Assobhei, O.; Gargiulo, E.; Palmieri, G.; Giardina, P.; Sannia, G. Roles of two white-rot basidiomycete fungi in decolourisation and detoxification of olive mill waste water. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2001, 57, 221–226. [Google Scholar]

- Robles, A.; Lucas, R.; De Cienfuegos, A.G.; Ga1vez, A. Phenoloxidase (laccase) activity in strains of the hyphomycete Chalara paradoxa isolated from olive mill wastewater disposal ponds. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2000, 26, 484–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leouifoudi, I.; Zyad, A.; Amechrou, Q.A.; Oukerrou, M.A.; Mouse, H.A.; Mbarki, M. Identification and characterisation of phenolic compounds extracted from Moroccan olive mill wastewater. Food Sci. Technol. Camp. 2014, 34, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issaoui, W.; Alexakis, D.D.; Hamdi, N.I.; Argyriou, A.V.; Alevizos, E.; Papadopoulos, N.; Inoubli, M.H. Monitoring olive oil mill wastewater disposal sites using sentinel-2 and planetscope satellite images: Case studies in Tunisia and Greece. Agronomy 2021, 12, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapia-Quirós, P.; Montenegro-Landívar, M.F.; Reig, M.; Vecino, X.; Cortina, J.L.; Saurina, J.; Granados, M. Recovery of Polyphenols from Agri-Food By-Products: The Olive Oil and Winery Industries Cases. Foods 2022, 11, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niaounakis, M.; Halvadakis, C.P. Olive Processing Waste Management 5: Literature Review and Patent Survey, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Komilis, D.P.; Aratzas, E.; Halvadakis, C.P. The effect of olive mill wastewater on seed germination after various pretreatment techniques. J. Environ. Manag. 2005, 74, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oukili, O.; Chaouch, M.; Rafiq, M.; Hadji, M.; Hamdi, M.; Benlemlih, M. Bleaching of olive mill wastewater by clay in the presence of hydrogen peroxide. Ann. Chim. Sci. Mat. 2001, 26, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Acqui, L.P.; Sparvoli, E.; Agnelli, A.; Santi, C.A. Olive oil mills waste waters and clay minerals interactions: Organics transformation and clay particles aggregation. In Proceedings of the 17th World Congress Soil Science, International Soil Society 2002, Bangkok, Thailand, 14–21 August 2002; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Ismaili, S.; Zrelli, A.; Ghorbal, A. Experimental study on the inhibition of glucose and olive mill wastewater degradation by volatile fatty acids in anaerobic digestion. Euro-Mediterr. J. Environ. Integr. 2024, 9, 637–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Meteorology. Annual Report 2020, Tunisia; National Institute of Meteorology: Brasília, Brazil, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ben Amor, O.; Elhechi, A.; Srasra, E.; Zargouni, F. Physicochemical and ceramic properties of clays from Jebel Kebar (Central Tunisia). Surf. Eng. Appl. Electrochem. 2016, 53, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 6060:1989; Water Quality—Determination of the Chemical Oxygen Demand, 2nd Edition. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 1989.

- World Health Organization. WHO Contribution in Tunisia (2019–2023): Evaluation Report; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025; ISBN 978-92-4-011353-4.

- European Commission. European Competitiveness Report; Office for Official Publications of the European Communities: Luxembourg, 2006; ISBN 92-79-02578-3.

- Hamdi, N.; Della, M.; Srasra, E. Experimental study of the permeability of clays from the potential sites for acid effluent storage. Desalination 2005, 185, 523–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paredes, C.; Cegarra, J.; Roig, A.; Sa’nchez-Monedero, M.A.; Bernal, M.P. Characterization of olive mill wastewater (alpechin) and its sludge for agricultural purposes. Bioresour. Technol. 1999, 67, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhag, M.; Zhang, L.; Boteva, S.; Yilmaz, N.; Chaabani, A. Mapping Pollution Risks: Geo-Information and Multi-Criteria Analysis in Olive Mill Wastewater Management. Water Air Soil. Pollut. 2025, 236, 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigui, S.; Kallel, A.; Hechmi, S.; Jedidi, N.; Trabelsi, I. Improvement and protection of olive mill waste-contaminated soils using low-cost natural additives. Euro-Mediterr. J. Environ. Integr. 2024, 9, 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dich, A.; Abdelmoumene, W.; Belyagoubi, L.; Assadpour, E.; Benhammou, N.B.; Zhang, F.; Jafari, S.M. Olive oil wastewater: A comprehensive review on examination of toxicity, valorization strategies, composition, and modern management approaches. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2025, 32, 6349–6379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibraheem, I.M.; Yogeshwar, P.; Bergers, R.; Tezkan, B. Joint interpretation of magnetic, transient electromagnetic, and electric resistivity tomography data for landfill characterization and contamination detection. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 30616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibraheem, I.M.; Yogeshwar, P.; Sharifi, F.; Bergers, R.; Tezkan, B. Joint inversion of transient electromagnetic and radiomagnetotelluric data for enhanced subsurface characterization. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 25494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loukil, E.; Gargouri, K.; Ben Mbarek, H.; Soua, N.; Ouhibi, T.; Gargouri, N.K.; Rigane, H. Application of electrical resistivity tomography method for the assessment of olive mill wastewater infiltration in storage basin site (southeastern Tunisia). Arab. J. Geosci. 2021, 14, 1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Range/Average Value |

|---|---|

| pH | 4.5–5.2 |

| EC (mS/cm) | 8–16 |

| COD (g/L) | 45–130 |

| BOD (g/L) | 35–100 |

| Suspended solids (g/L) | 1–9 |

| TS (g/L) | 60–120 |

| Mineral solids (g/L) | 5–15 |

| VS (g/L) | 55–105 |

| Sugar (g/L) | 10–80 |

| Pectins, mucilage and tannins (g/L) | 3.7–15 |

| Polyalcohols (g/L) | 1.1–15 |

| Polyphenols (g/L) | 5–24 |

| Fats (g/L) | 0.5–10 |

| Organic acids (g/L) | 5–10 |

| Amino acids (g/L) | 2.8–20 |

| PO42− (g/L) | 0.8 |

| Na+ (g/L) | 5.37 |

| K+ (g/L) | 15.29 |

| Ca++ (g/L) | 1.17 |

| Mg++ (g/L) | 0.41 |

| Mn++ (g/L) | 0.01 |

| Cl− (g/L) | 0.27 |

| SO42− (g/L) | 0.01 |

| Parameters | OMW Samples | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E1 | E2 | E3 | OMW After [5] | |

| pH | 4.5 | 6 | 5.2 | 4.5–5.2 |

| COD(g/L) | 48 | 70 | 80 | 45–130 |

| Total organic carbon (g/L) | 12.5 | 15.85 | 110 | - |

| TS (g/L) | 50 | 34 | 80 | 60–120 |

| VS (g/L) | 44 | 25 | 60 | 55–105 |

| Fats (g/L) | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 0.5–10 |

| Polyphenols (g/L) | 5 | 9.7 | 14 | 5–24 |

| Total N (g/L) | 2.8 | 1.5 | 6.8 | - |

| C/N | 5.5 | 12.5 | 12.5 | - |

| Total P (g/L) | 0.096 | 0.45 | 1.1 | 0.8 |

| K (g/L) | 5.2 | 5.364 | 7.2 | 15.29 |

| Na (g/L) | 0.12 | 0.636 | 0.7 | 5.37 |

| Ca (g/L) | 0.045 | 0.85 | 0.9 | 1.17 |

| Mg (g/L) | 0.1 | 0.164 | 0.2 | 0.41 |

| Fe (mg/L) | 35 | 60 | 50 | - |

| Control Point (CP) (mg Eq AG/gMS) | Borehole (I) (mg Eq AG/gMS) | Borehole (II) (mg Eq AG/gMS) | Borehole (III) (mg Eq AG/gMS) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CP20 = 0.13 | I80 = 0.15 | II60 = 0.19 | III40 = 0.34 |

| CP40 = 0.19 | I280 = 0.31 | II140 = 0.24 | III100 = 0.8 |

| - | I440 = 0.36 | II280 = 0.26 | III120 = 0.3 |

| - | - | II340 = 0.36 | III180 = 0.28 |

| - | - | - | III340 = 0.27 |

| - | - | - | III400 = 0.31 |

| - | - | - | III500 = 0.3 |

| Samples | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polyphenols (mg/L) | 13.17 | 10 | 41 |

| pH | 7.8 | 7.3 | 7.5 |

| EC (mS/cm) | 1.9 | 1.6 | 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Issaoui, W.; Nasr, I.H.; Inoubli, M.H.; Ibraheem, I.M. Assessment of Soil and Groundwater Contamination from Olive Mill Wastewater Disposal at Ben Aoun, Central Tunisia. Water 2026, 18, 149. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020149

Issaoui W, Nasr IH, Inoubli MH, Ibraheem IM. Assessment of Soil and Groundwater Contamination from Olive Mill Wastewater Disposal at Ben Aoun, Central Tunisia. Water. 2026; 18(2):149. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020149

Chicago/Turabian StyleIssaoui, Wissal, Imen Hamdi Nasr, Mohamed Hédi Inoubli, and Ismael M. Ibraheem. 2026. "Assessment of Soil and Groundwater Contamination from Olive Mill Wastewater Disposal at Ben Aoun, Central Tunisia" Water 18, no. 2: 149. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020149

APA StyleIssaoui, W., Nasr, I. H., Inoubli, M. H., & Ibraheem, I. M. (2026). Assessment of Soil and Groundwater Contamination from Olive Mill Wastewater Disposal at Ben Aoun, Central Tunisia. Water, 18(2), 149. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020149