1. Introduction

Understanding the hydrological cycle is fundamental for decision-making in hydrological and environmental domains, including flood and drought forecasting as well as water quality control. Its importance has grown in recent years in the context of climate change, where the management of water resources is becoming increasingly critical. Runoff simulation, in particular, is a prerequisite for quantitatively capturing and predicting the interactions among key hydrological components, such as precipitation, evapotranspiration, and soil moisture dynamics [

1]. Accurate and precise streamflow simulations are essential for quantitatively assessing watershed-scale runoff characteristics and predicting hydrological responses [

2,

3].

Hydrological models are tools for quantitatively analyzing the water cycle by representing complex hydrological processes within a watershed using mathematical equations and physical relationships. These models are widely applied for various purposes, including water resources management at the watershed scale, flood forecasting, sediment yield analysis, and water quality assessment. Depending on their structure and complexity, hydrological models can be classified into conceptual and distributed models. One of the representative models, the Soil and Water Assessment Tool (SWAT), divides a watershed into hydrologically homogeneous sub-basins and simulates long-term runoff and water cycling based on combinations of soil properties, land use, and topography [

4,

5]. Similarly, the recently developed Dynamic Water Resources Assessment Tool (DWAT) model has demonstrated excellent performance in simulating watershed-scale water balance processes. Among semi-distributed models, the Precipitation Runoff Modeling System (PRMS) and, among conceptual models, the TANK model have also traditionally shown high performance in hydrological simulations [

6,

7].

Studies have been extensively conducted to compare and evaluate the structural characteristics and simulation performance of various hydrological models to improve the accuracy of runoff simulation. Early studies primarily focused on conceptual models such as the TANK model and the PRMS, aiming to simplify and interpret the rainfall–runoff relationship within watersheds, while emphasizing their applicability and computational efficiency in data-limited watersheds.

Subsequently, distributed models that incorporate spatial characteristics such as soil, terrain, and land use have been developed, with a focus on enabling more realistic runoff simulations. Notably, the SWAT has been used to quantify water cycling of watersheds through long-term hydrological simulations, and numerous studies have assessed the accuracy of the SWAT model across various regions [

8,

9]. In particular, multiple studies have reported that the SWAT model demonstrates high simulation accuracy following parameter calibration and is particularly effective in modeling water cycles in agricultural watersheds [

10].

A distributed model, DWAT, has recently been developed, and subsequent studies have demonstrated its superior simulation performance relative to conventional hydrological models, particularly with respect to temporal and spatial resolution. The DWAT model offers the advantage of more accurately representing watershed responses to topographic variation, land cover heterogeneity, and diverse rainfall events by reflecting interactions among detailed hydrological components within the watershed. In contrast, conceptual models such as the TANK model simulate rainfall–runoff relationships using a simple reservoir structure, enabling efficient runoff estimation in watersheds with limited observed data. The TANK model is frequently employed as a reference model in comparative studies with more complex physically based models [

11].

A number of studies have evaluated and compared the performance of distributed and conceptual hydrological models in runoff simulations [

12,

13,

14]. For example, Kebede et al. (2014) [

15] compared hydrological simulation results over the Baro-Akobo basin in Ethiopia using the physically based distributed hydrological model, known as the Water Flow and Balance Simulation Model (WaSiM), and the conceptual model, the Hydrologiska Byråns Vattenbalansavdelning (HBV) model. For an objective comparison, the models were forced with identical climate input variables so that only the effects of differences in model structure were evaluated. The results showed that both models performed well in simulating runoff during the reference periods, with WaSiM performing better for peak flow simulation and HBV indicating a tendency to overestimate low flows. The study suggested that simple conceptual models are suitable for hydrological simulation in data-scarce regions, while physically based distributed models are preferable for detailed hydrological process analysis. In addition, Okiria et al. (2022) [

16] compared the hydrological simulation performance of the conceptual TANK model and the semi-distributed TOPMODEL for the Atari river watershed in Africa. The results indicated that both models successfully captured the seasonal variation and rainfall–runoff response, with TOPMODEL showing more stable performance than the TANK model during both the calibration and validation periods. Aqnouy et al. (2023) [

17] aimed to evaluate the rainfall–runoff simulation performance and identify the most suitable type of hydrological model for the Oued Laou watershed in Morocco by comparing three hydrological models with different structures: SWAT, HEC-HMS, and the ATelier Hydrologique Spatialisé (ATHYS) model. The comparison results showed that all three models performed well in simulating observed runoff, with the SWAT model exhibiting the best overall performance. The study concluded that in watersheds with high heterogeneity in topography and land use, a multi-model comparison approach is more effective than relying on a single model for improving the understanding of water hydrological characteristics and reducing uncertainty.

Therefore, comparing and evaluating hydrological models with distinct structures, such as the DWAT, PRMS, and TANK models, under identical conditions holds academic significance, as it elucidates the characteristics of runoff simulations associated with model structure and features, and provides a basis for selecting the most suitable model under diverse watershed conditions.

A number of studies remain confined to specific watersheds or individual models, and studies that directly compare multiple hydrological models under uniform conditions are scarce. In particular, studies that analyze the impact of structural distinctions between conceptual models such as TANK, PRMS and distributed models, such as DWAT, on runoff simulation performance remain limited.

Therefore, this study applies three hydrological models within the same watersheds to quantitatively compare and evaluate their runoff simulation performance according to each model’s structural characteristics, thereby providing empirical evidence for model selection and applicability.

The structure of this study is as follows:

Section 2 describes the study area where the three hydrological models were applied, the input datasets for modeling, the concepts and characteristics of each model, and the statistical criteria used for model performance evaluation.

Section 3 presents a quantitative comparison of runoff simulations generated by the models and evaluates the simulation results according to their temporal characteristics.

Section 4 discusses the advantages and limitations of each model for runoff simulation and provides considerations on the applicability of hydrological models for runoff simulation under various watershed conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

To ensure a fair and consistent comparison among the three hydrological models (DWAT, PRMS, and TANK), a unified methodological framework was established in this study. Identical spatial, meteorological, and hydrological datasets were applied to all models, and the same simulation periods were used throughout data preprocessing, model setup, calibration, validation, and performance evaluation. Specifically, the 12-year simulation period was strictly divided into a calibration period (2012–2019) and an independent validation period (2020–2023) for all three models. Model calibration and validation were conducted using identical time periods and objective functions to minimize potential bias arising from differences in calibration intensity or data availability. The overall workflow of the study, including data collection, preprocessing, model application, calibration and validation, and performance evaluation, is summarized in

Figure 1. Finally, model performance was quantitatively evaluated and compared using nine statistical metrics (including R

2, NSE, LogNSE, KGE, RMSE, MAE, RE (%), VE, and RSR) to comprehensively assess the influence of model structural differences on simulation accuracy.

2.1. Study Area

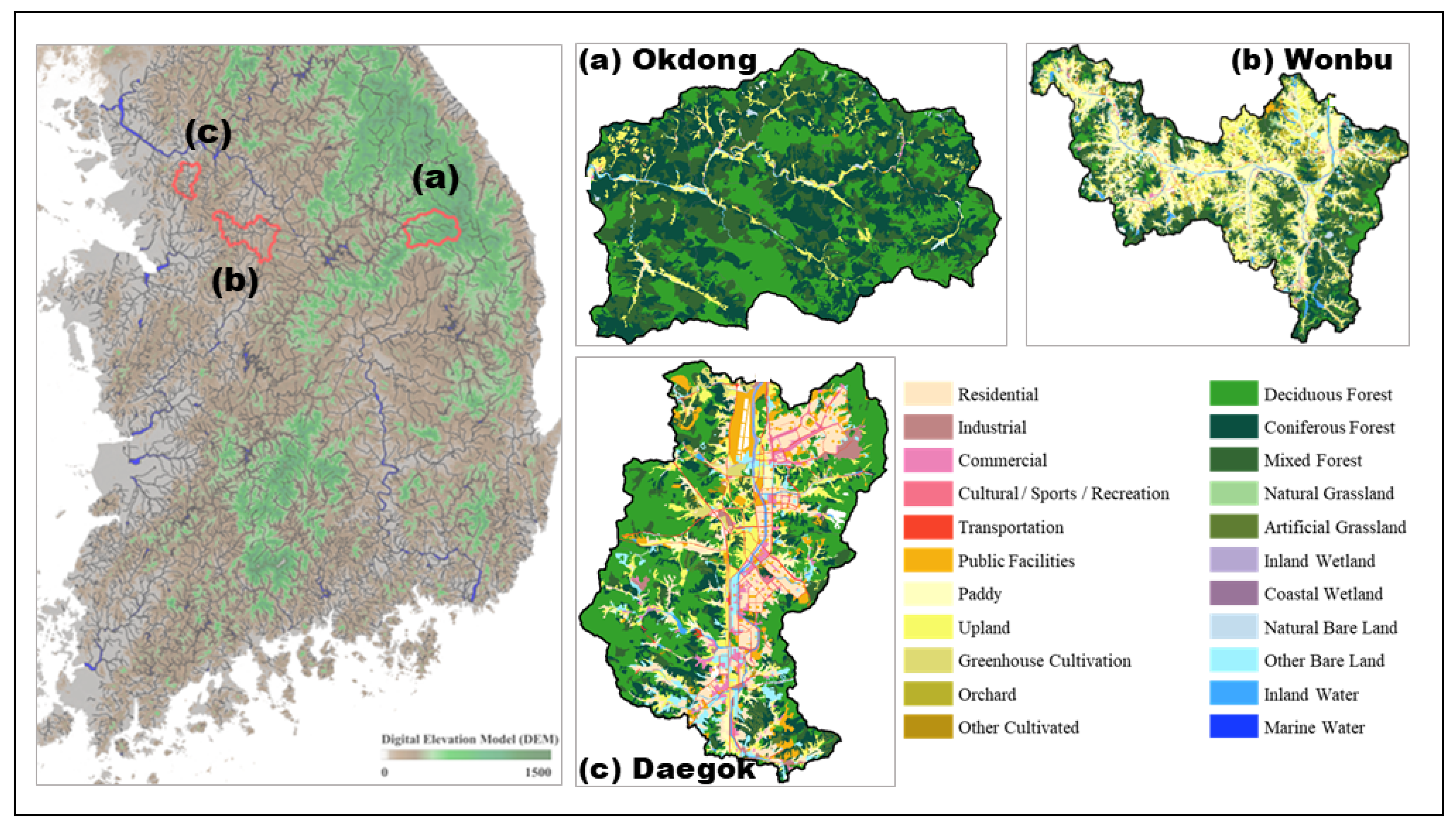

This study was conducted in a watershed encompassing three gauging stations in the Republic of Korea: Okdong-gyo in Yeongwol-gun, Gangwon Province; Wonbu-gyo in Yeoju-si; and Daegok-gyo in Seoul Metropolitan City. Each watershed was selected to represent distinct topographic and land-use characteristics, namely mountainous, mixed, and urban types. The Okdong-gyo watershed is a typical mountain stream, characterized by steep slopes and a high proportion of forest cover. Approximately 93.2% of the watershed area is covered by forest, resulting in high infiltration rates and relatively low surface runoff under normal rainfall conditions (

Figure 2).

Table 1 presents the topographic characteristics of the three study sites, highlighting the differences in slope and land use. Among them, the Wonbu-gyo watershed represents a mixed river basin, encompassing a variety of land use types, including agricultural land, forest, and urban areas. Consequently, the rainfall–runoff processes are complexly influenced by both natural and anthropogenic factors, resulting in diverse spatial and temporal runoff characteristics. Lastly, the Daegok-gyo watershed, located in Seoul Metropolitan City, is an urban river basin characterized by a high degree of urbanization and extensive paved areas. Approximately 27% of the total watershed area is classified as urban. This urbanized environment leads to increased runoff and shortened hydrological response times due to the expansion of impervious areas. This study was conducted on these three watersheds with distinct topographic and land use characteristics to compare and evaluate the applicability of various hydrological models and their performance in runoff simulation.

The study watersheds are located in the central region of Korea, which falls within a temperate monsoon climate zone characterized by four distinct seasons and pronounced heavy rainfall during the summer. The annual precipitation ranges from approximately 1200 to 1500 mm, of which about 60–70% occurs during the monsoon and typhoon season from June to September. During the summer season, localized intense rainfall and short-duration downpours often frequently occur, leading to rapid increases in runoff over short periods, whereas winter precipitation is low and most of it occurs in the form of snowfall. Such seasonal variability in rainfall serves as a major driver of hydrological responses, which differ according to watershed characteristics including topography and land-use patterns.

2.2. Datasets

Table 2 summarizes the meteorological input variables used for each model, with particular emphasis on differences arising from model-specific potential evapotranspiration (PET) estimation methods. Spatial inputs such as land use, basin boundaries, and soil properties, as well as hydrological inputs related to runoff generation and streamflow routing, were commonly applied to all three models and are illustrated in the overall methodological framework. Therefore,

Table 2 focuses on meteorological variables, for which input requirements differ among DWAT, PRMS, and TANK.

In this study, daily meteorological data of precipitation, maximum, minimum, and air temperature were collected for the three basins to be used as input data for hydrological models, covering a 12-year period from 2012 to 2023. As meteorological data critically influence the reliability of long-term hydrological model simulations, spatially distributed observation networks were utilized, and the quality of all meteorological datasets was carefully reviewed prior to model application. In Korea, the major hydrometeorological data providers used in this study (Flood Control Office (FCO), Korea Meteorological Administration (KMA), Korea Water Resources Corporation (K-water), Korea Rural Community Corporation (KRC), and Korea Hydro & Nuclear Power (KHNP)) conduct rigorous quality-control (QC) procedures as part of routine data production and management. Building on these institutional QC processes, an additional “double-check” screening was performed to ensure that the input time series used for model comparison were internally consistent and free from obvious errors that could bias model calibration and evaluation.

Specifically, the datasets were screened for missing values, physically unrealistic records, and temporal inconsistencies. For precipitation, this included checks for negative values, prolonged zero-precipitation periods inconsistent with nearby stations, and abrupt discontinuities indicative of sensor or logging errors. For air temperature, missing values, outliers, and common processing errors—such as cases where daily maximum and minimum temperatures were inadvertently reversed (i.e., Tmax < Tmin)—were carefully examined. When such issues were identified, the affected records were either excluded from the final input series or corrected through cross-comparison with nearby stations and consistency checks across the observation network.

These preprocessing steps were applied uniformly across the three study watersheds to minimize the influence of input-data artifacts on the comparative evaluation of DWAT, PRMS, and TANK. Evapotranspiration was subsequently estimated using model-specific approaches, taking into account the computational structure and input requirements of each hydrological model. For the DWAT and TANK models, potential evapotranspiration was estimated using the Penman–Monteith method, which comprehensively accounts for meteorological factors, whereas the PRMS model employed the Hargreaves method, requiring fewer input variables and simplifying energy-based calculations. Notably, the DWAT and PRMS models are designed to automatically calculate potential evapotranspiration internally within the models, while the TANK model, due to its structural characteristics, requires evapotranspiration to be externally calculated based on mean temperature and subsequently provided as input data.

Table 2 presents the characteristics of the input data for each model.

Precipitation data were obtained from multiple observation networks listed in the Annual Reports of Hydrological Survey on Korea (2012–2023). Data from rainfall gauging stations operated by the Flood Control Office (FCO), Korea Meteorological Administration (KMA), Korea Water Resources Corporation (K-water), Korea Rural Community Corporation (KRC), and Korea Hydro & Nuclear Power (KHNP) were consolidated to ensure spatial representativeness of the dataset. As the installation purposes and operating conditions of gauging stations differ among institutions, the use of multiple networks minimized potential spatial bias that could arise from relying on a single source. The collected precipitation data were used to estimate representative rainfall for each basin by applying the Thiessen-polygon method to calculate spatial weights, taking into account the density and locations of the gauging stations to derive Thiessen coefficients for each station.

Temperature data, including maximum, minimum, and mean temperatures, were obtained from the Automated Surface Observing System (ASOS) operated by the Korea Meteorological Administration (KMA). The ASOS network provides long-term, stable observed data that undergo quality control (QC), enabling their use to generate substitute input data for evapotranspiration estimation, such as solar radiation, humidity, and wind speed. The collected ASOS data were also processed using the Thiessen-polygon method to calculate Thiessen coefficients for estimating representative temperatures within each basin. This data preprocessing minimizes the influence of input data differences on model performance comparisons, enabling a clearer analysis of the effects of model structural characteristics and parameter differences on the simulation results.

2.3. Hydrological Models

Approaches for simulating hydrological processes within a basin vary according to the structure and objectives of the models. For long-term water resources planning and management, or for quantitative assessment on the impacts of land-use changes on hydrological cycles, long-term runoff models that can incorporate the physical characteristics of the basin are essential.

The criteria for model selection should comprehensively consider (1) applicability, considering the climatic and topographic characteristics of the study area; (2) accuracy, referring to the model’s ability to simulate runoff volume and peak discharge; (3) objectivity in parameter estimation; and (4) practicality, referring to the ease of data preparation and model operation for users.

In this study, the Dynamic Water Resources Assessment Tool (DWAT) was selected as the primary model for quantitatively analyzing the water cycle in the basins. DWAT was developed by the Han River Flood Control Office of the Ministry of Environment and the Korea Institute of Civil Engineering and Building Technology (KICT) specifically to accommodate local hydrological conditions. It is a semi-distributed model based on a link–node type using physical parameters, in which the catchment is divided into sub-catchments that are considered hydrologically homogeneous. In particular, DWAT integrates with a GIS preprocessing module to facilitate convenient extraction of input parameters, simulates runoff separately for pervious and impervious areas, and includes a paddy-specific runoff module reflecting agricultural characteristics in Asia, thereby ensuring high applicability to basins in Korea.

As comparative models, the TANK and PRMS models, both widely used for long-term runoff simulations, were selected for their structural distinction from DWAT.

The TANK model is a conceptual lumped model developed by Sugawara [

18]. As the model simplifies a basin into virtual storage tanks, it features a simple structure and requires minimal input data, facilitating its application. Moreover, having been developed in Japan, where climatic and topographic conditions are similar to those of Korea, the TANK model has been widely applied to domestic watersheds, thereby making it an appropriate choice for use as a comparative model.

The Precipitation Runoff Modeling System (PRMS) is a deterministic, semi-distributed model developed by the United States Geological Survey (USGS). By subdividing a basin into hydrologic response units (HRUs), PRMS offers high objectivity in parameter estimation using GIS and is appropriate for evaluating the hydrological impacts of land-use changes. The three selected models exhibit clear distinctions in simulating key hydrological components, including precipitation, evapotranspiration, infiltration, and runoff. The theoretical characteristics of each model are as follows.

2.3.1. Dynamic Water Resources Assessment Tool (DWAT)

The Dynamic Water Resources Assessment Tool (DWAT) is a semi-distributed hydrological model that represents the water cycle of a watershed using a link–node structure. It is designed to consistently simulate and analyze surface and groundwater flows based on physical parameters. Representative average rainfall for each sub-basin is derived using the Thiessen-polygon method, accounting for spatial imbalances in the observation network, and applied as input to the model. DWAT offers a dedicated QGIS-based plugin that allows for overlaying spatial data such as basin boundaries, land use, and soil maps to generate sub-basins. The plugin also automatically creates the DWAT Project files required for model operation, thereby enhancing its practical applicability in both research and operational settings [

19].

Estimation of evapotranspiration can be performed by calculating potential evapotranspiration using either the Penman–Monteith or the Hargreaves method. Actual evapotranspiration is calculated by applying FAO 56 crop coefficients, Leaf Area Index (LAI), or Monthly Coefficients. The infiltration process is calculated based on the soil’s hydraulic conductivity and multiple infiltration modules, such as Rainfall Excess, Green–Ampt, and Horton methods are provided, enabling flexible application under different soil and climatic conditions. The model also performs separate runoff simulations for pervious and impervious zones, enabling more realistic runoff modeling in both urban and rural areas. In particular, it incorporates a paddy-field runoff module that reflects hydrological characteristics specific to Asia, allowing runoff and return-flow simulations that account for ponding depth and weir height in rice paddies.

The model supports various channel routing methods, including Muskingum, Muskingum Cunge, and Kinematic Wave, and provides an automatic calibration feature based on model-independent Parameter ESTimation (PEST) and SCE-UA for parameter estimation.

Based on its structural flexibility, physical consistency, and practical applicability, DWAT has been selected as one of the hydrological models recommended by the World Meteorological Organization’s (WMO) HydroSOS (Hydrological Status and Outlook System), with wide international applicability. The model, along with its manual, video tutorials, executable files, and example datasets, is freely available via the WMO website, providing high accessibility for users.

2.3.2. Precipitation Runoff Modeling System (PRMS)

The Precipitation-Runoff Modeling System (PRMS) is a deterministic, semi-distributed hydrological model developed by the United States Geological Survey (USGS). The model subdivides a basin into hydrologically homogeneous units, referred to as Hydrologic Response Units (HRUs), based on basin characteristics such as slope, vegetation, and soil type [

20]. Point precipitation data are adjusted using HRU-specific correction factors and used as model input, while interception is calculated as a function of vegetation cover density and maximum interception storage. PRMS provides several options for estimating potential evapotranspiration, including the Hamon method, the modified Jensen–Haise method, and the pan evaporation method with monthly coefficients. In this study, potential evapotranspiration was estimated using the Hargreaves method (Equation (1)), which requires relatively fewer input variables and is suitable for long-term hydrological simulations.

Here,

is a coefficient,

denotes solar radiation, and

represents the mean daily air temperature. Runoff generation in PRMS is represented through five storage components: interception, impervious layer, lower zone, subsurface, and groundwater. Surface runoff is determined based on the concept of the runoff-contributing area. Channel routing is conducted using the Modified-Puls routing method (Equation (2)), and parameter optimization can be performed using methods such as the Rosenbrock method.

Here, denotes the storage at day , represents the outflow at day , and is the inflow.

2.3.3. TANK

The TANK model, developed by Sugawara [

18], is a conceptual lumped model designed to simulate the rainfall–runoff processes of a watershed through a series of interconnected storage tanks. Although the standard structure typically consists of four tanks (TANK4), three-tank versions are widely employed in Korea to better reflect local watershed characteristics [

21,

22]. The governing equation of the TANK model is given as follows (Equation (3)).

In this equation,

and

represent the outflows from the upper and lower outlets of the first tank, respectively, while

and

denote the outflows from the outlets of the second and third tanks. Furthermore, for long-term runoff simulation, the storage of the

-th tank and time

(

) can be estimated using the following equation.

Here, is the storage of the -th tankon day , indicates the rainfall of subsurface drainage from the upper tank on day , is the outflow on day , denotes evapotranspiration, and represents subsurface drainage.

Rainfall input uses the watershed-averaged precipitation calculated through methods such as the Thiessen-polygon method, whereas evapotranspiration is usually accounted for as a loss from the storage in the uppermost tank (first tank). Infiltration is conceptually simulated as vertical water movement from upper to lower tanks through infiltration outlets at the tank base; in some modified versions, Horton or Green-Ampt methods are applied. Each tank corresponds to a distinct runoff component: the first tank simulates surface runoff, the second tank intermediate flow, and the third and fourth tanks baseflow (groundwater flow).

2.4. Model Calibration and Validation Strategy

To ensure a fair comparison among the three hydrological models, DWAT, PRMS, and TANK were calibrated and validated using identical time periods and observational datasets. The calibration period covered 2012–2019, and the validation period covered 2020–2023 for all models, allowing direct comparison of model performance under the same hydroclimatic conditions.

For model calibration, a consistent objective function based primarily on the Nash–Sutcliffe efficiency (NSE) was adopted across all three models. Additional performance metrics, including R2 and RMSE, were used to support the evaluation of calibration adequacy. Although each model differs in structural complexity and parameterization schemes, the calibration process was conducted following a unified evaluation framework to minimize potential bias arising from calibration procedures.

Parameter calibration for DWAT was performed using its built-in automatic optimization module based on the SCE-UA algorithm. For PRMS and TANK, parameter sets documented in national water management practices were used as initial estimates. Specifically, the TANK model parameters were based on those applied in the National Water Resources Plan of Korea, while PRMS parameters were informed by applications within the Comprehensive Flood Control Plan for major river basins.

For these two models, iterative manual calibration was conducted by adjusting key sensitive parameters identified in previous studies. In the TANK model, calibration focused on storage and outflow coefficients governing surface, intermediate, and baseflow components, whereas for PRMS, parameters related to soil moisture storage, groundwater recession, and runoff generation were selectively adjusted. These parameters were refined from the national plan-based initial values to better reflect watershed-specific hydrological characteristics, rather than relying solely on default or empirical settings.

Formal parameter sensitivity and uncertainty analyses were not conducted in this study. However, the authors acknowledge that differences in parameter sensitivity among models may influence the final simulation results. Based on the iterative manual calibration for TANK and PRMS, and the optimization results from DWAT, the parameters most critical to controlling the overall runoff volume and flow dynamics were identified. For the TANK model, the storage and outflow coefficients governing baseflow and intermediate flow were the most influential. For PRMS, parameters related to soil moisture capacity and groundwater recession were highly sensitive. In the physically based DWAT model, the saturated hydraulic conductivity and the storage coefficient were found to be highly influential in partitioning rainfall into surface runoff, infiltration, and regulating the basin’s flow response. This limitation (absence of formal sensitivity analysis) has been explicitly considered in the interpretation of comparative model performance to avoid over-attributing differences solely to model structural advantages.

2.5. Model Performance Evaluation Criteria

Various statistical indicators have been used to quantitatively evaluate the simulated runoff from hydrological models. In this study, nine metrics, including the coefficient of determination (R

2), NSE, logarithmic NSE (LogNSE), Kling-Gupta efficiency (KGE), root mean square error (RMSE), mean absolute error (MAE), relative error (RE), volumetric error (VE), and the standardized RMSE (RSR), were employed to compare and assess the runoff simulation performance of three hydrological models: DWAT, PRMS, and TANK. These metrics provide a statistical measure of the models’ ability to accurately simulate both the variability and magnitude of observed streamflow. The formulas and interpretation criteria for each metric are presented in

Table 3.

In general, R

2, NSE, KGE, and LogNSE values closer to 1 indicate greater model fit, whereas lower values of RMSE, MAE, RE, VE, and RSR closer to 0 correspond to smaller errors and higher simulation accuracy [

23,

24,

25]. Since NSE and LogNSE exhibit different sensitivities to peak and low flows, considering both metrics together allows for a more effective assessment of runoff simulation performance. In this study, a combination of complementary evaluation metrics was employed to comprehensively assess the simulation performance of each hydrological model and to objectively compare the predictive capabilities associated with different model structures.

is the observed runoff; is the simulated runoff; and are the mean observed and simulated streamflows, respectively; is the number of observed data; and are the total observed and simulated streamflow volumes; is the correlation coefficient; is the ratio of standard deviations; and is the ratio of means.

2.6. Statistical Comparison of Model Performance

In this study, non-parametric statistical methods were applied to examine whether differences in performance among the three hydrological models, DWAT, TANK, and PRMS, are statistically significant. Conventional performance indices such as NSE, RMSE, and KGE are useful for summarizing model performance; however, they have limitations when used to statistically determine the relative superiority of multiple models. In particular, hydrological time series often violate the assumptions of normality and independence due to strong temporal autocorrelation, making the direct application of parametric statistical tests inappropriate. Therefore, this study employed non-parametric statistical tests based on time-step-wise error distributions.

In this context, a time step refers to each observation point of the daily discharge data used for model calibration and validation. Accordingly, time-step-wise errors were constructed as the differences between observed and simulated daily discharge values over the analysis period. The same temporal resolution and number of samples were consistently applied across all basins and models to ensure comparability.

The statistical comparison was conducted using model errors calculated at each time step rather than aggregated performance indices. For a given model m at time step two types of errors were defined.

First, the absolute error represents the magnitude of the difference between simulated and observed discharge and was used to evaluate overall model error.

where

denotes the simulated discharge produced by model m, and

denotes the observed discharge at the same time step.

Second, to better capture relative differences under low-flow conditions, a log-transformed error was additionally defined as follows:

where

ε is a small constant introduced to prevent numerical issues associated with zero discharge values. In this study,

was used. The log-transformed error was particularly employed to ensure consistency with the low-flow performance analysis based on the Q90 threshold.

Considering the non-normality and repeated-measure characteristics of hydrological time series data, non-parametric statistical tests were adopted. A Friedman test was first applied to evaluate whether overall differences in error distributions existed among the three models. The Friedman test ranks model errors at each time step and assesses whether differences in mean ranks are statistically significant, making it suitable for repeated-measure data.

When the Friedman test indicated statistically significant differences, post hoc pairwise comparisons were conducted using Dunn’s test. The post hoc analysis was performed for the following model pairs: DWAT–TANK, DWAT–PRMS, and TANK–PRMS. Adjusted p-values were used to control for multiple comparisons.

All statistical analyses were conducted in the MATLAB R2024b environment, and identical procedures were applied to all basins to ensure consistency and reproducibility. The statistical comparison presented in this section is intended to complement, rather than replace, the performance evaluation based on conventional metrics, providing additional quantitative support for assessing the relative strengths and limitations of the three hydrological models.

3. Results

3.1. Performance Evaluation of DWAT, PRMS, and TANK Models

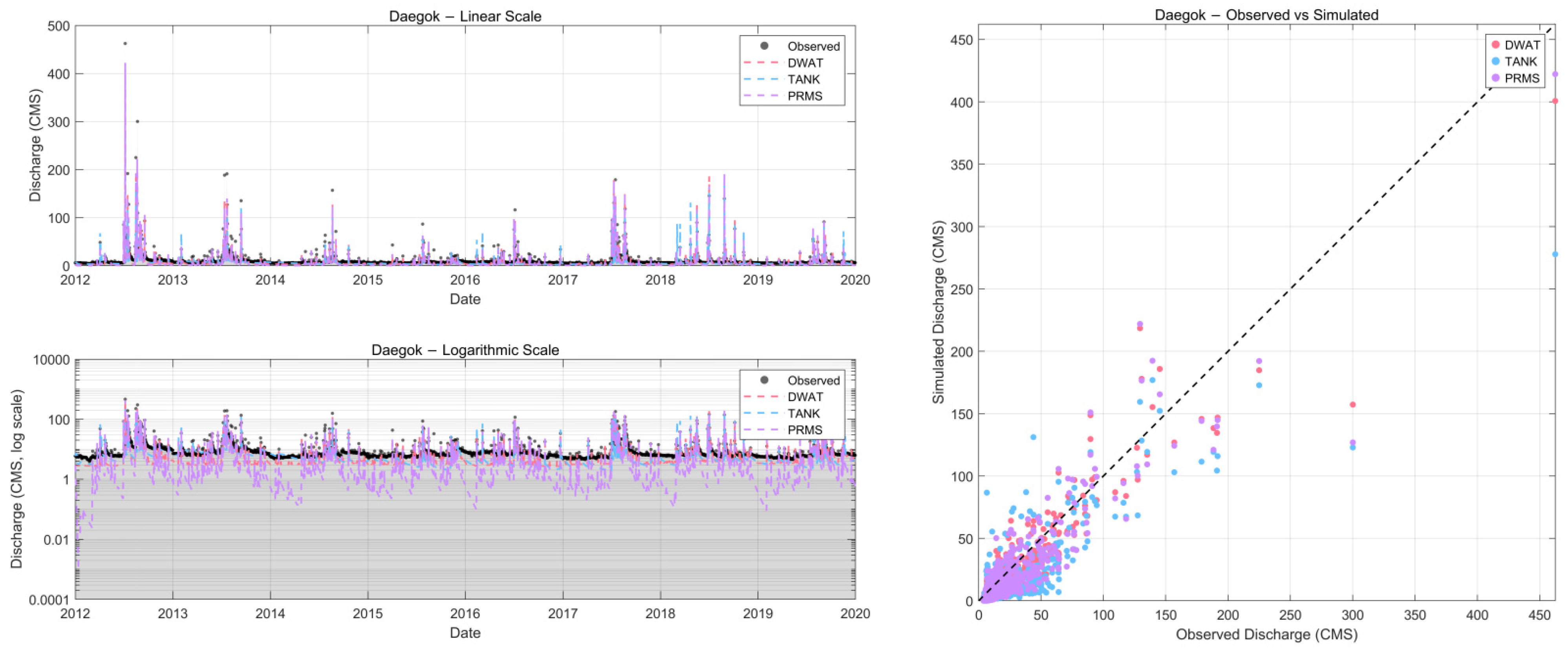

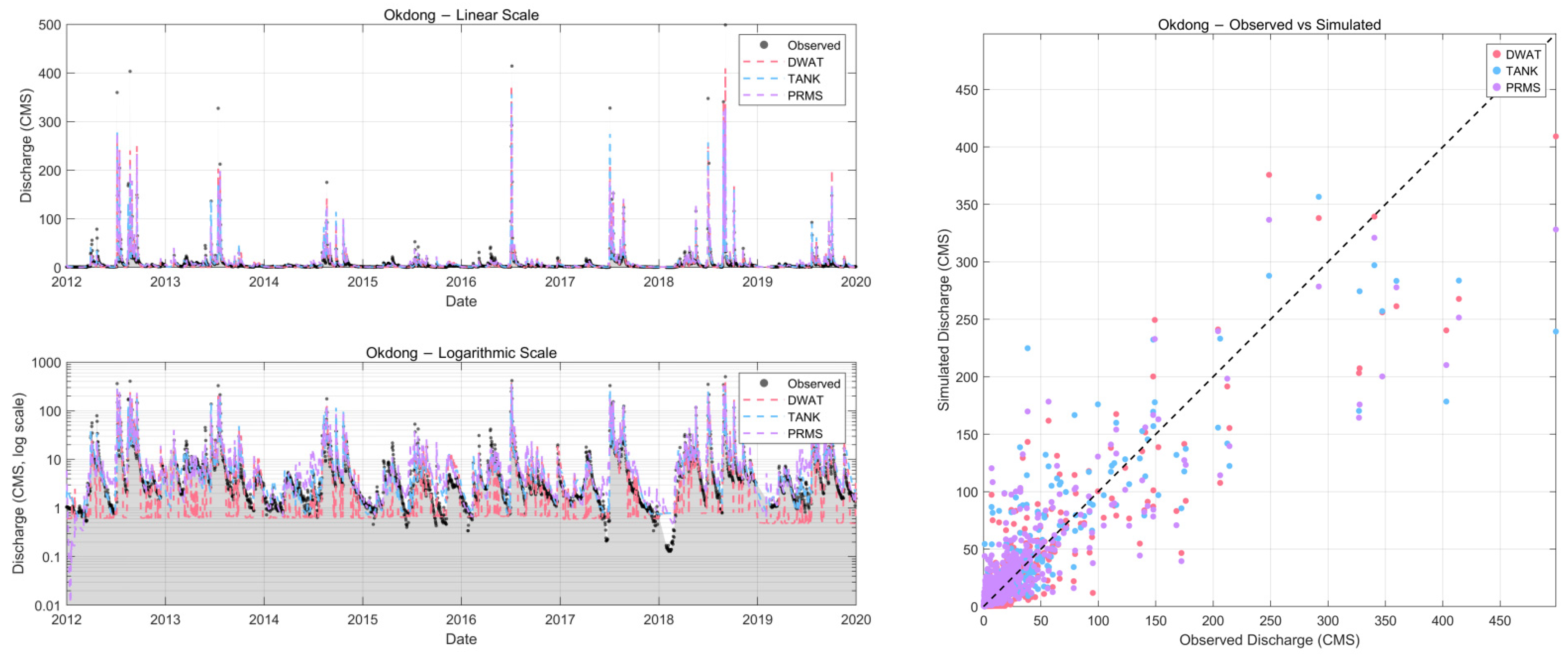

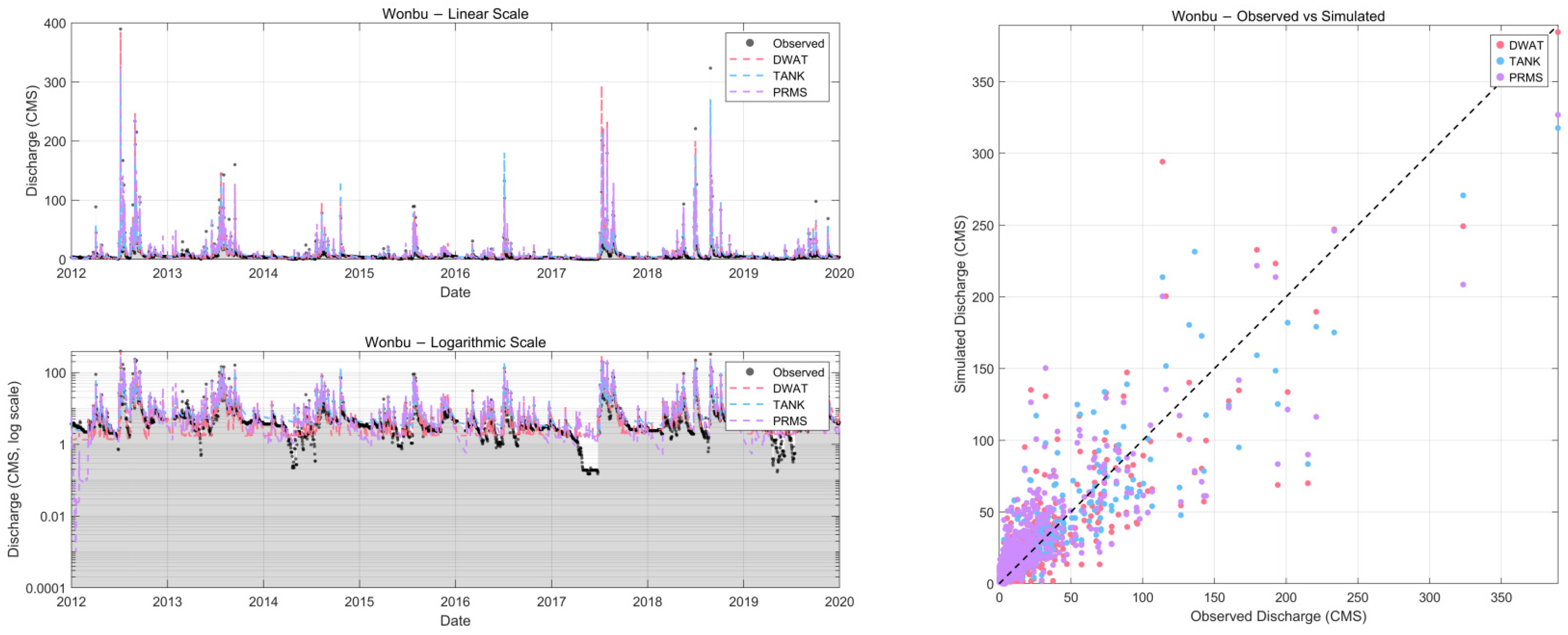

Overall, the scatter charts for the three sites indicate that simulated runoff from all three models, DWAT, TANK, and PRMS, generally increases with increasing observed runoff data; however, clear differences in model performance were evident (

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5). All three models exhibited relatively consistent distributions in the low-flow range in the scatter plots; however, as runoff magnitude increased, the points gradually deviated from the 1:1 line, indicating tendencies toward both overestimation and underestimation. In particular, PRMS exhibited a pronounced tendency to simulate runoff lower than the observed runoff under high-flow conditions, whereas the TANK model showed relatively stable performance in the low- to medium-flow ranges but exhibited increasing scatter as runoff increased. In contrast, DWAT produced distributions closest to the observed data values at all three sites, with points clustering around the 1:1 line, especially in highly urbanized basins such as Daegok-gyo, where rapid runoff responses occur. Taken together, DWAT demonstrated relatively high consistency and stability across basins with different characteristics, the TANK model tended to perform well in basins with complex land-use patterns, and PRMS showed reasonable accuracy in low-flow simulations but relatively lower performance under high-flow conditions.

3.2. Evaluation of Hydrologic Model Performance Using Statistical Metrics

Table 3,

Table 4 and

Table 5 present the runoff simulation performance of the three hydrological models evaluated using nine statistical metrics. At the Okdong-gyo site, all three models generally demonstrated good simulation performance; however, DWAT exhibited the highest overall accuracy. The R

2 and NSE values for DWAT were both 0.82, which were slightly higher than those obtained for TANK and PRMS. In addition, DWAT achieved the lowest RMSE and MAE values of 11.68 m

3/s and 4.24 m

3/s, respectively, indicating relatively accurate simulation of hydrological responses in steep, forested mountainous basins. In contrast, PRMS showed relatively larger errors, with a runoff error (RE) of 17.6%, indicating a tendency to slightly overestimate runoff. These results suggest that DWAT shows relatively strong performance in mountainous basins, which may be related to its ability to account for spatial variability in terrain and topographic characteristics under the conditions examined in this study.

At the Wonbu-gyo and Daegok-gyo sites, model performance varied depending on land-use characteristics and the degree of urbanization. At Wonbu-gyo, a mixed-use basin composed of agricultural land, forest, and urban areas, the TANK model achieved the highest simulation performance, with R2 = 0.83 and NSE = 0.82. This result suggests that the simple conceptual structure of the TANK model may be well suited to represent combined runoff responses under heterogeneous land-use conditions. DWAT also showed good performance at this site, particularly in terms of RMSE (9.75 m3/s) and MAE (3.71 m3/s), although a slight overestimation of runoff was observed (RE = 4.1%).

At the highly urbanized Daegok-gyo site, DWAT exhibited the highest accuracy, with R2 = 0.88 and NSE = 0.85 demonstrating strong agreement with observed runoff under conditions characterized by rapid runoff responses and high impervious surface coverage. In contrast, TANK and PRMS showed relatively lower performance, with NSE values of 0.69 and 0.75, respectively. PRMS, in particular, exhibited a pronounced tendency to underestimate runoff during low-flow periods, accompanied by substantial volume errors (RE = −51%).

The extremely negative LogNSE value obtained for PRMS at the Daegok-gyo site (LogNSE = −12.343) can be attributed to the combined effects of systematic underestimation of low flows and the logarithmic transformation applied in the LogNSE calculation. The Daegok-gyo basin frequently exhibits near-zero observed flows during dry periods, particularly during the winter season (January–February). In this study, LogNSE was calculated by applying a logarithmic transformation to both observed and simulated discharge values with a small constant added to avoid undefined values at zero discharge, i.e., log(Q + ε), where ε was set to 1 × 10−6. Under this formulation, even small absolute differences between observed and simulated flows can be substantially amplified in the log-transformed domain when observed discharge is close to zero. Consequently, the persistent underestimation of winter low flows by PRMS led to large deviations in the logarithmic space, resulting in the extremely negative LogNSE value. This behavior reflects the inherent sensitivity of the LogNSE metric to low-flow simulation errors rather than numerical instability or calculation errors.

Overall, the comparative results suggest that conceptual models such as TANK may perform well in mixed-use basins, while the spatially distributed DWAT model demonstrates strong performance in highly urbanized basins under the conditions considered in this study.

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6 present the performance metrics of DWAT, TANK, and PRMS under low-flow conditions, defined as discharge values equal to or lower than the 90th percentile (Q90) of observed daily streamflow for each basin. The calculated Q90 thresholds were 16.09 m

3/s for the Okdong basin, 13.90 m

3/s for the Wonbu basin, and 16.34 m

3/s for the Daegok basin, indicating comparable low-flow regimes across the three study basins. Under these low-flow conditions, all models exhibited negative R

2 values, reflecting the limited variability of observed discharge and confirming that R

2 is not an appropriate primary indicator for evaluating model performance during low-flow periods. Accordingly, model evaluation focused on RMSE, log-transformed RMSE (logRMSE), and percent bias (PBIAS), which are more robust for assessing model behavior in low-flow regimes.

In the Daegok basin (

Table 7), DWAT and TANK showed comparable logRMSE values, indicating similar capability in reproducing low-flow variability; however, both models tended to underestimate low flows, as reflected by negative PBIAS values. In contrast, PRMS exhibited substantially larger errors and stronger negative bias, suggesting limited applicability under low-flow conditions. In the Okdong basin (

Table 8), the TANK model achieved the lowest logRMSE, demonstrating superior representation of low-flow variability, while DWAT showed smaller bias magnitude, indicating better reproduction of low-flow volumes. PRMS consistently overestimated low flows and exhibited higher error levels. For the Wonbu basin (

Table 9), DWAT yielded the lowest logRMSE with relatively moderate bias, suggesting the most balanced low-flow performance among the three models. The TANK model showed a tendency toward overestimation, whereas PRMS again demonstrated higher errors and lower consistency.

Overall, the results highlight that model performance under low-flow conditions varies depending on basin characteristics. Storage-based models such as TANK tend to perform well in basins dominated by baseflow processes, whereas DWAT demonstrates relatively stable performance across basins with differing hydrological and land-use characteristics. PRMS showed comparatively weaker performance under low-flow conditions across all study basins, indicating structural limitations in simulating low-flow dynamics.

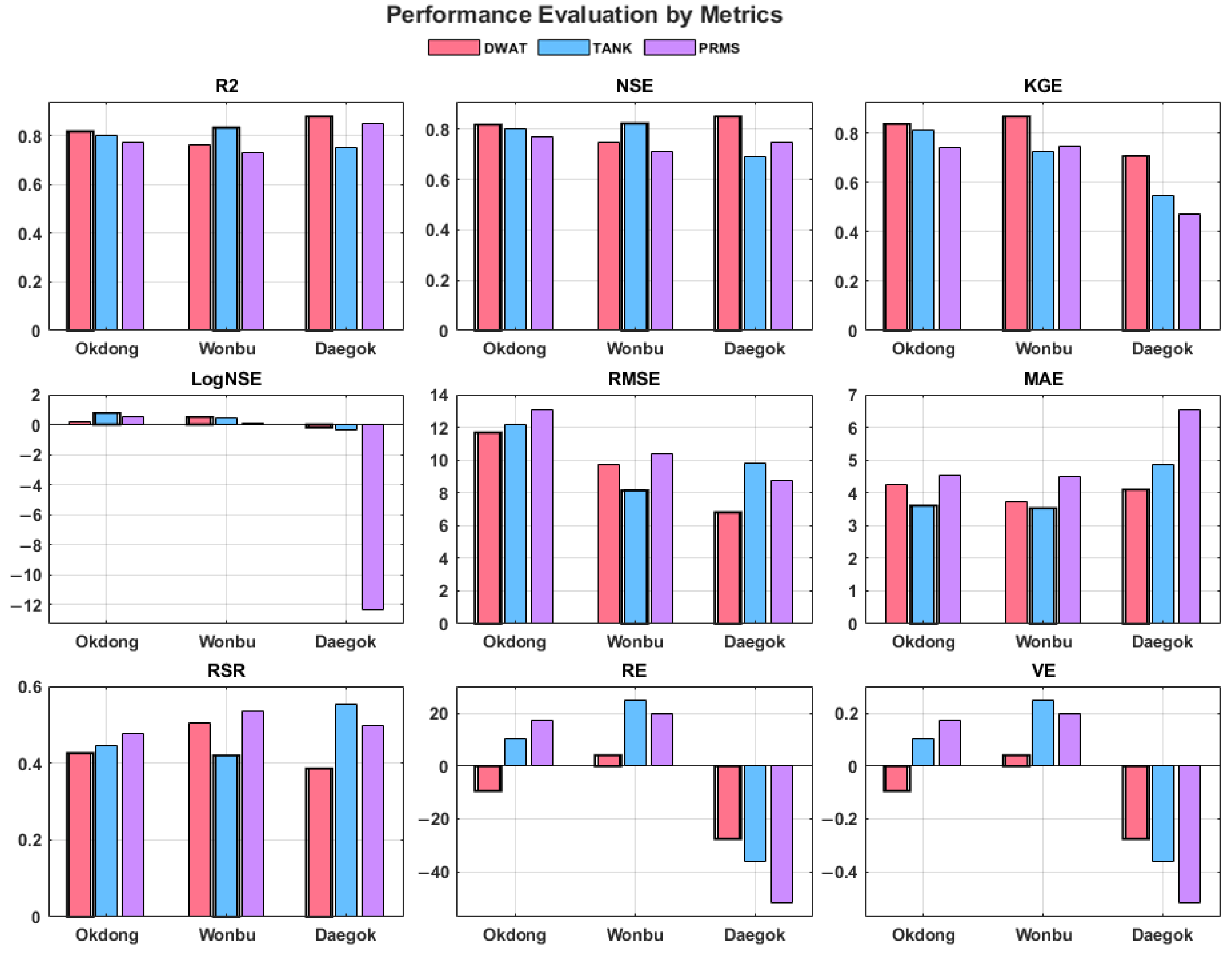

A comprehensive analysis of performance metrics across the three sites indicated that the DWAT model generally exhibited relatively stable and superior performance across most indicators. In

Figure 6, the black frames highlight the best-performing model for each evaluation metric at each site. At Okdong-gyo, DWAT and TANK showed similar R

2, NSE, and KGE values; however, DWAT achieved the lowest RMSE and RSR, confirming its superior simulation performance in mountainous basins. PRMS displayed relatively lower accuracy in key efficiency metrics and showed highly unstable results in LogNSE, highlighting its limitations in simulating low-flow conditions. At Wonbu-gyo, TANK achieved the highest R

2 and NSE values, but PRMS exhibited relatively large deviations in RSR, RMSE, and MAE, suggesting that errors were substantially amplified in this mixed-use basins.

At the highly urbanized Daegok-gyo site, DWAT exhibited the best performance among the three models. DWAT achieved the highest values of R2, NSE, and KGE, as well as the lowest RMSE, MAE, and RSR, effectively capturing the rapid and highly variable runoff characteristics resulting from urbanization. In contrast, PRMS showed large errors across most metrics and exhibited severely negative LogNSE values, indicating limitations in simulating both low- and high-flow conditions. TANK demonstrated intermediate performance; however, relatively large over- or underestimation in RE and VE suggested that it insufficiently reflected the nonlinear hydrological responses of urban basins. These results indicate that model performance varies clearly across basin types from mountainous to mixed-use to urbanized, and that the spatially distributed DWAT model provides consistently reliable runoff simulations across diverse topographic and land-use conditions.

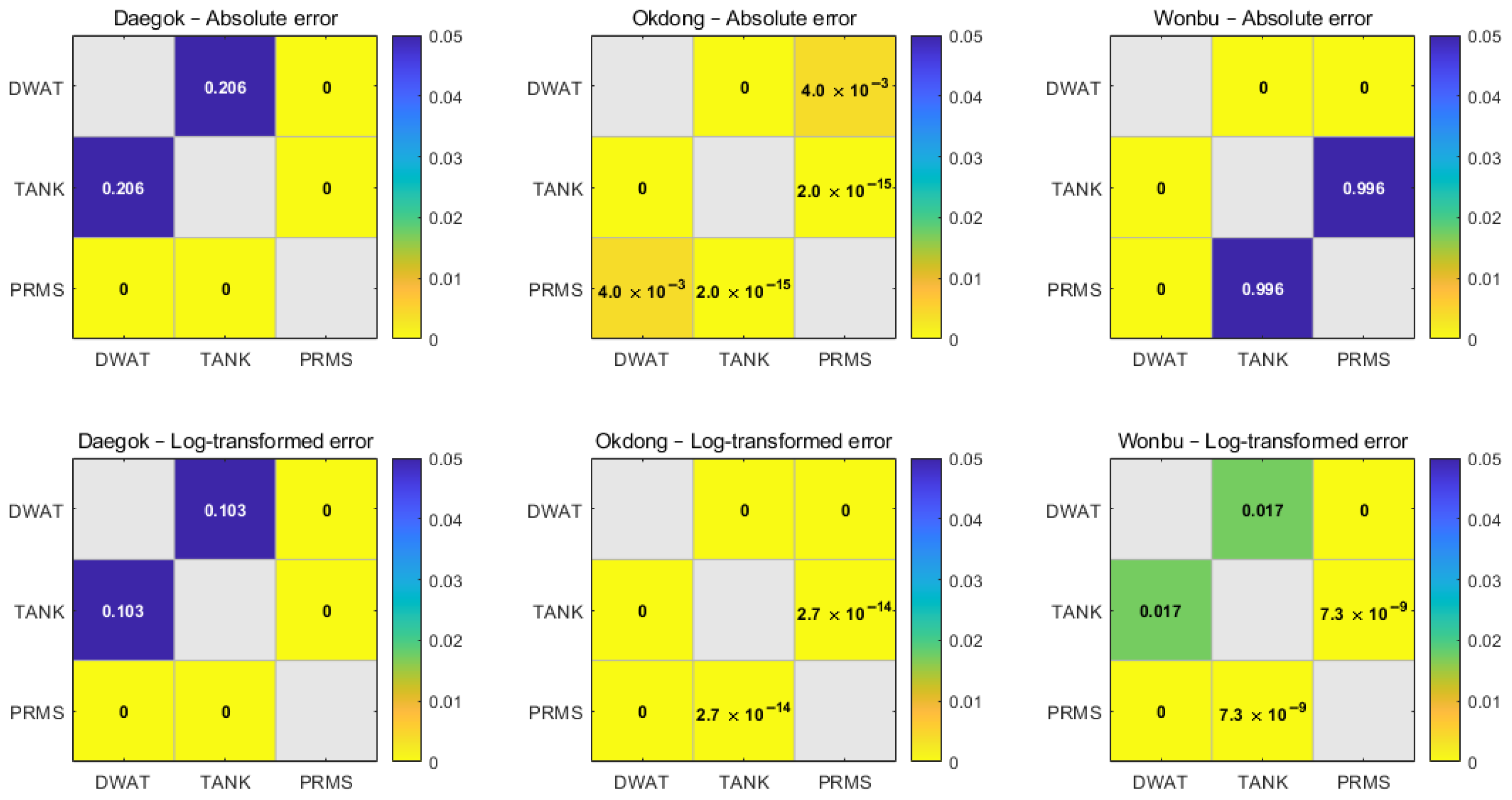

3.3. Results of Statistical Comparison of Model Performance

The Friedman test revealed statistically significant differences among the three hydrological models for both absolute and log-transformed errors across all basins (p < 0.001), indicating that the overall error distributions of DWAT, TANK, and PRMS are not statistically equivalent.

Post hoc Dunn tests further clarified the pairwise differences among models. PRMS consistently exhibited significantly larger error distributions than DWAT and TANK in all basins for both error measures (p < 0.05), confirming its relatively lower performance. In contrast, differences between DWAT and TANK were basin-dependent: they were statistically significant in the Okdong and Wonbu basins, whereas no significant difference was detected in the Daegok basin, indicating comparable performance under storage-dominated hydrological conditions.

The results of the Friedman tests for each basin are summarized in

Table 10, while detailed

p-values from the post hoc Dunn tests are summarized in

Table 11.

Post hoc Dunn test results summarized in

Table 11 indicate that PRMS exhibited significantly larger errors than DWAT and TANK in all basins for both absolute and log-transformed errors (

p < 0.05). In the Okdong basin, all pairwise model comparisons showed statistically significant differences, indicating clear distinctions among model performances across the full flow range. In the Wonbu basin, TANK and PRMS did not differ significantly in terms of absolute error; however, their performances were statistically distinguishable when log-transformed errors were considered, highlighting differences under low-flow conditions. In contrast, no statistically significant differences were observed between DWAT and TANK in the Daegok basin for either error measure, suggesting comparable performance under storage-dominated hydrological conditions.

In addition to the tabulated results,

Figure 7 provides a visual summary of the post hoc Dunn test results, highlighting the relative strength and consistency of statistical differences among model pairs across basins. The heatmap representation clearly illustrates that PRMS exhibits strong and persistent differences compared to DWAT and TANK in most basin–error combinations, as indicated by uniformly low

p-values. Differences between DWAT and TANK, however, show distinct basin-dependent patterns, with non-significant results observed in the Daegok basin and significant differences emerging in the Okdong and Wonbu basins. This visual comparison reinforces the conclusions drawn from

Table 11 by emphasizing both the magnitude and spatial consistency of model performance differences.

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretation of Model Performance Across Basin Types

The results of this study indicate that no single hydrological model consistently outperforms the others across all watershed types. Instead, model performance is strongly influenced by the compatibility between basin characteristics and model structure. This finding highlights that the relative strengths of hydrological models emerge under different dominant hydrological processes rather than from inherent model superiority.

In the mountainous Okdong-gyo basin, both DWAT and TANK demonstrated relatively strong performance. The steep topography and high forest coverage result in runoff responses that are primarily controlled by terrain and baseflow processes. Under such conditions, conceptual storage-based models as well as semi-distributed models can provide reasonable runoff simulations. Similar tendencies have been reported in previous comparative hydrological modeling studies conducted in natural and mountainous basins.

In the mixed-use Wonbu-gyo basin, the TANK model showed the best overall performance among the three models. This basin includes agricultural land, forest, and urban areas, where runoff generation is governed by a combination of surface runoff, interflow, and baseflow components. The multi-reservoir conceptual structure of the TANK model appears to effectively integrate these combined runoff responses. Comparable results have been observed in earlier studies, suggesting that conceptual models can perform robustly in basins characterized by heterogeneous land-use conditions.

In contrast, the highly urbanized Daegok-gyo basin exhibited the strongest performance for the DWAT model. The ability of DWAT to explicitly distinguish between pervious and impervious areas and to incorporate spatially distributed basin information likely contributed to its superior performance in capturing rapid runoff responses and high flow variability typical of urban watersheds. This result is consistent with findings from previous studies emphasizing the importance of spatial representation when simulating runoff in urbanized basins.

In addition, the comparative outcomes of this study are consistent with previous evaluations of distributed and conceptual hydrological models. Earlier studies have shown that both model types can successfully reproduce observed runoff when using identical climate inputs while revealing structural differences in peak-flow and low-flow simulation [

15]. Other comparisons have demonstrated that semi-distributed models such as TOPMODEL often exhibit more stable performance than conceptual models like TANK in seasonally varying basins [

16]. Furthermore, multi-model assessments conducted in heterogeneous watersheds have emphasized that no single model is universally superior, and that using multiple model structures can enhance the understanding of hydrological responses and reduce uncertainty under complex physiographic conditions [

17]. These findings support the conclusion that model suitability is highly basin-dependent and that structural diversity among hydrological models remains valuable for robust watershed analysis.

4.2. Implications of Low-Flow (Q90) and Log-Transformed Performance Metrics

The low-flow analysis based on the Q90 threshold provided additional insights that could not be fully captured by performance metrics calculated over the entire flow range. Under low-flow conditions, all models exhibited negative R2 values, reflecting the limited variability of observed discharge and confirming that correlation-based metrics are not suitable as primary indicators for low-flow performance evaluation.

Accordingly, this study focused on RMSE, log-transformed RMSE, and percent bias to assess model behavior during low-flow periods. Across all basins, PRMS consistently showed larger errors and stronger bias under low-flow conditions. This behavior was particularly evident in the log-transformed metrics, where small absolute differences between observed and simulated flows were amplified when observed discharge approached zero.

The extremely negative LogNSE values obtained for PRMS in the urban basin can be attributed to the sensitivity of logarithmic performance metrics to low-flow errors rather than to numerical instability. Such sensitivity of log-transformed indices to low-flow conditions has been widely reported in hydrological modeling studies and should be carefully considered when interpreting model performance in low-discharge regimes.

In contrast, DWAT generally exhibited relatively balanced low-flow performance across basins, showing moderate bias and stable error distributions. The TANK model performed well in certain basins in terms of reproducing low-flow variability but showed basin-dependent bias behavior. These results suggest that model performance under low-flow conditions is strongly influenced by the dominant storage and release mechanisms represented in each model.

4.3. Interpretation of Statistical Comparison Results

The non-parametric statistical analysis provided quantitative support for the performance differences observed using conventional evaluation metrics. The Friedman test revealed statistically significant differences among the three models for both absolute and log-transformed errors across all basins, indicating that the observed performance differences are not attributable to random variability.

Post hoc Dunn test results further clarified that PRMS exhibited significantly larger error distributions than DWAT and TANK in all basins for both error types. This finding statistically confirms the relatively lower performance of PRMS observed in the performance metric analysis. In contrast, differences between DWAT and TANK were basin-dependent. In the Daegok-gyo basin, no statistically significant difference was detected between these two models, suggesting comparable performance under storage-dominated and highly regulated runoff conditions. However, significant differences emerged in the Okdong-gyo and Wonbu-gyo basins, reflecting the influence of basin characteristics on relative model behavior.

These statistical results reinforce the interpretation that hydrological model performance should be evaluated in the context of basin-specific hydrological processes rather than through a single aggregated performance index.

4.4. Implications for Hydrological Model Selection

The findings of this study emphasize that hydrological model selection should be guided by watershed characteristics and modeling objectives rather than by a generalized perception of model complexity or sophistication. Semi-distributed models that incorporate spatial heterogeneity may offer advantages in urbanized basins, whereas conceptual models can provide efficient and reliable simulations in natural or mixed-use basins when dominant hydrological processes are adequately represented.

DWAT demonstrated stable performance across all basin types considered in this study, indicating its practical applicability under diverse hydrological conditions. The TANK model showed strong performance in basins with combined runoff processes, while PRMS exhibited limitations under both high-flow and low-flow conditions in the studied basins. Overall, the integrated evaluation framework employed in this study—combining multiple performance metrics, low-flow analysis, and non-parametric statistical testing—provides a robust basis for comparative hydrological model assessment and supports more informed model selection decisions.

5. Conclusions

This study conducted a comprehensive comparison of runoff simulation performance using three hydrological models—DWAT, PRMS, and TANK—across three watersheds representing mountainous (Okdong-gyo), mixed-use (Wonbu-gyo), and urbanized (Daegok-gyo) conditions under identical input data, calibration periods, and evaluation criteria.

Overall results based on nine performance metrics (R2, NSE, LogNSE, KGE, RMSE, MAE, RE, VE, and RSR) indicate that the DWAT model exhibited the most stable and consistently high performance across all basin types. In particular, DWAT achieved the highest accuracy in the highly urbanized Daegok-gyo basin, with NSE = 0.85 and R2 = 0.88, effectively capturing rapid runoff responses associated with high impervious surface coverage. These results highlight the advantage of DWAT’s semi-distributed structure and explicit representation of pervious and impervious areas in urban hydrological applications.

The TANK model demonstrated its strongest performance in the mixed-use Wonbu-gyo basin, where it achieved NSE = 0.82 and R2 = 0.83. This suggests that the conceptual multi-reservoir structure of the TANK model is well suited to representing combined runoff processes in basins characterized by heterogeneous land-use patterns. In contrast, PRMS consistently showed lower performance, particularly under high-flow conditions, where systematic underestimation resulted in large volumetric errors (RE reaching −52% at the Daegok-gyo basin).

Low-flow performance was further evaluated using a Q90 threshold (16.09 m3/s for Okdong, 13.90 m3/s for Wonbu, and 16.34 m3/s for Daegok). Under these conditions, correlation-based metrics such as R2 were found to be inappropriate due to limited discharge variability. Instead, RMSE, log-transformed RMSE, and PBIAS provided more robust indicators of model behavior. DWAT showed relatively balanced low-flow performance across all basins, whereas PRMS exhibited consistently larger errors and stronger bias, particularly in log-transformed metrics, indicating structural limitations in simulating low-flow dynamics.

Non-parametric statistical comparisons based on time-step-wise error distributions further supported these findings. Friedman tests revealed statistically significant differences among the three models across all basins for both absolute and log-transformed errors (p < 0.001). Post hoc Dunn tests confirmed that PRMS exhibited significantly larger error distributions than DWAT and TANK in all basins, while differences between DWAT and TANK were basin-dependent. No significant difference was detected between DWAT and TANK in the urban Daegok-gyo basin, suggesting comparable performance under storage-dominated conditions.

These results demonstrate that hydrological model performance is strongly dependent on basin characteristics rather than the inherent superiority of a single model. Semi-distributed models such as DWAT are particularly effective in urbanized basins, while conceptual models like TANK can provide reliable simulations in mixed-use or natural basins when dominant hydrological processes are adequately represented.

This study provides a quantitative and statistically supported basis for hydrological model selection according to basin type. Nevertheless, several limitations should be acknowledged. Despite the use of identical calibration periods and evaluation frameworks, differences in structural complexity and parameter sensitivity among models imply that equivalent levels of parameter optimization cannot be strictly guaranteed. In addition, the focus on daily runoff limits the assessment of short-duration extreme events.

Future research should extend this comparative framework to a broader range of climatic and physiographic conditions, incorporate formal parameter uncertainty analyses, and evaluate model performance under seasonal and extreme flood scenarios. Such efforts would further enhance the understanding of the structural strengths and limitations of DWAT, PRMS, and TANK and support more informed hydrological modeling applications.