Low-Carbon Operation Strategies for Membrane-Aerated Biofilm Reactor Through Process Simulation and Multi-Objective Optimization

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Framework of Selection Methods

2.2. Process Influent and Effluent Scenario Settings

2.3. Process Simulation

2.4. Evaluation Criteria

- Q—Wastewater treatment plant effluent flow rate, m3/d;

- n—The number of pollutants examined in the EQI assessment;

- wi—Proportion weight of pollutants in EIQ;

- Si—The concentration of the i-th pollutant in EQI.

- OCI—Operating costs, in USD/m3;

- Care—Energy cost, electricity fee 0.093 USD/kWh;

- Cche—Pharmaceutical cost, carbon source cost 0.34 USD/kg, PAC cost 0.15 USD/kg.

- Cdisp—Sludge disposal cost, with sludge transportation cost at 80 USD/t.

- GHG—Greenhouse gas emissions, measured in kgCO2eq/m3;

- AD—Emission source activity data, unit depends on the calculated emission source;

- EF—Emission factor, unit depends on the unit of activity data;

- —Concentration of influent pollutants, mg/L;

- —Concentration of effluent pollutants, mg/L;

- GWP—Global warming potential, GWP CH4 is 25 kgCO2eq/kgCH4, GWP N2O is 298 kgCO2eq/kgN2O.

2.5. Non-Dominated Sorting Method

3. Results and Discussion

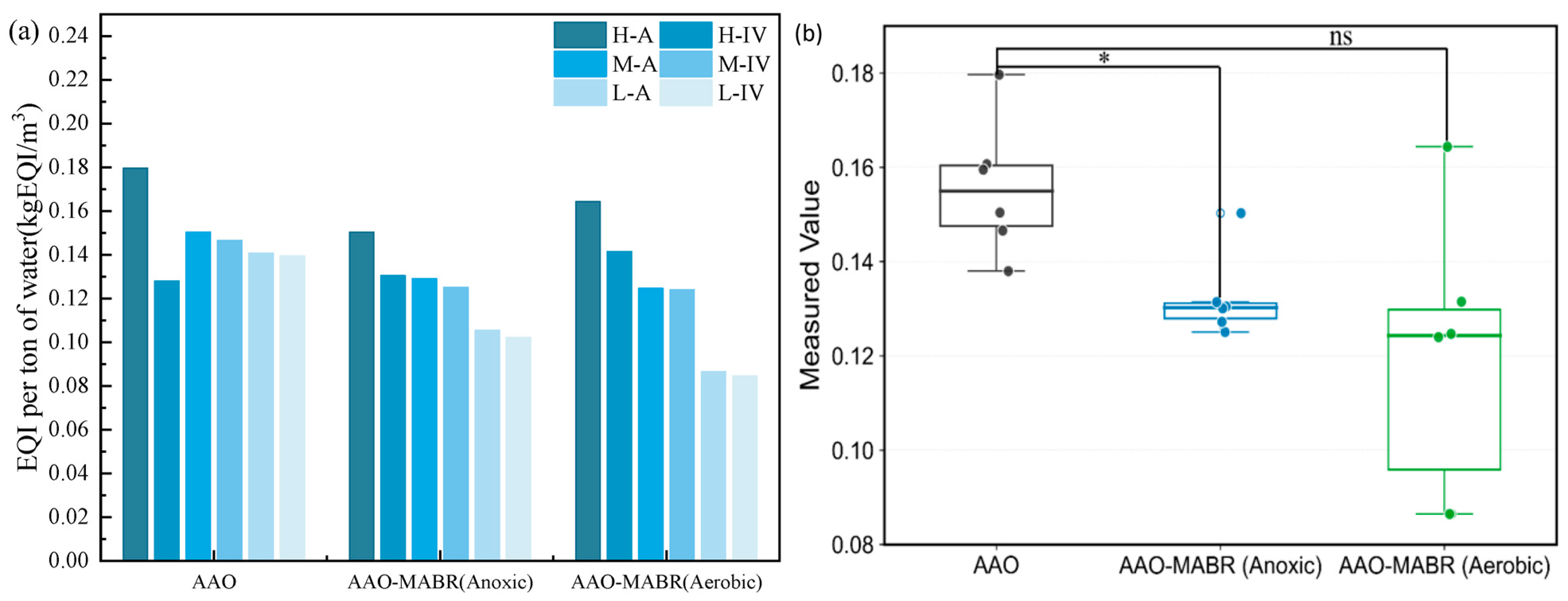

3.1. Characteristics of Process Effluent Quality

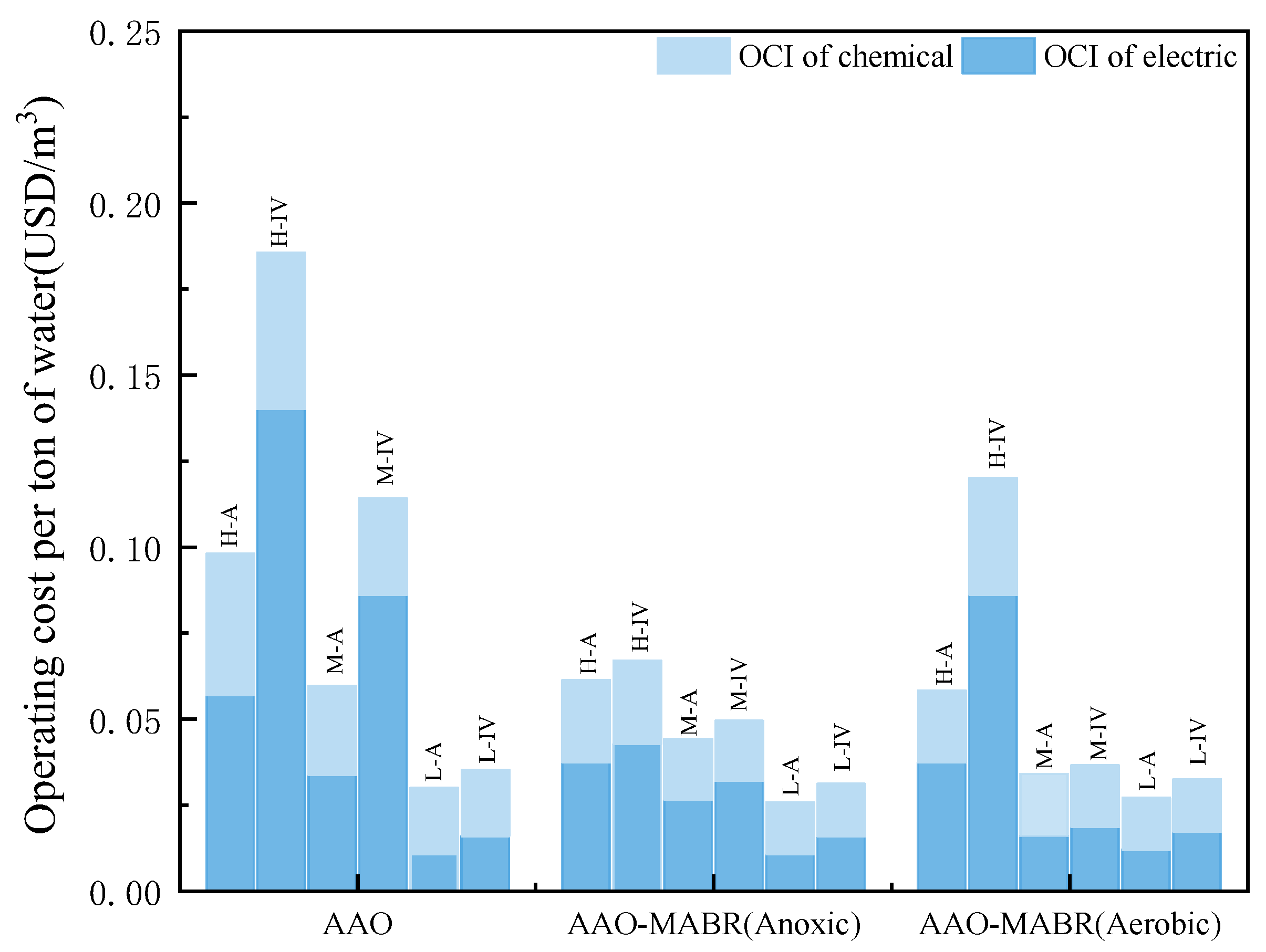

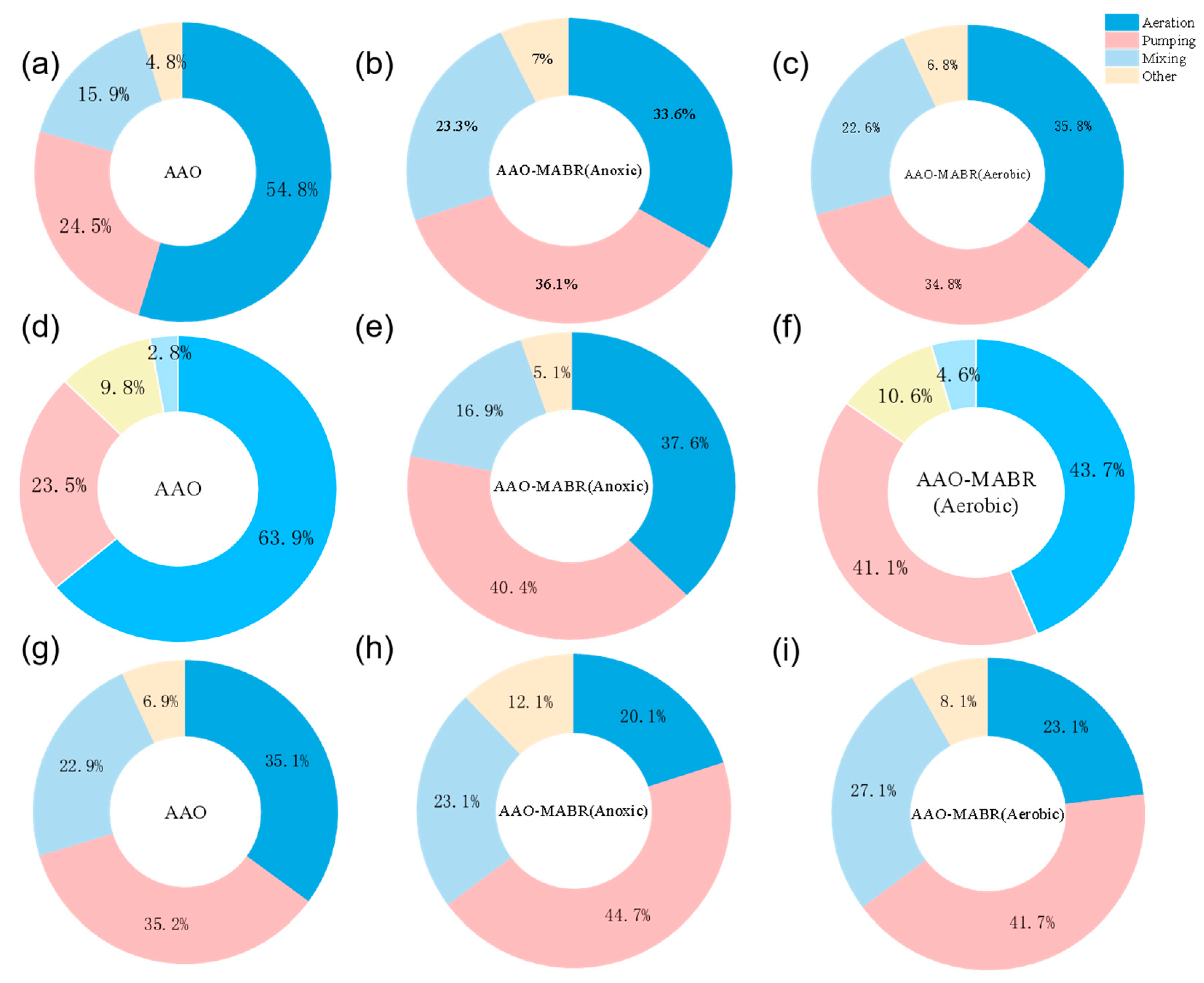

3.2. Process Operating Cost Characteristics

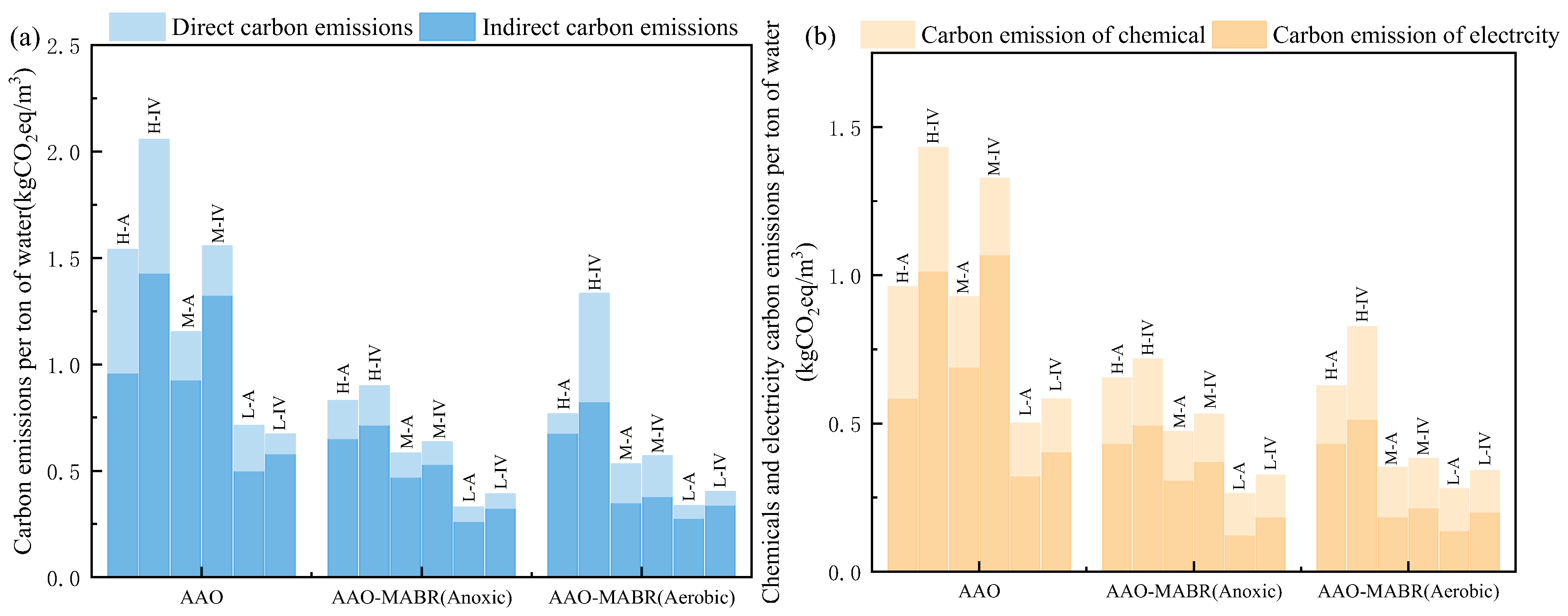

3.3. Characteristics of Carbon Emissions from Industrial Processes

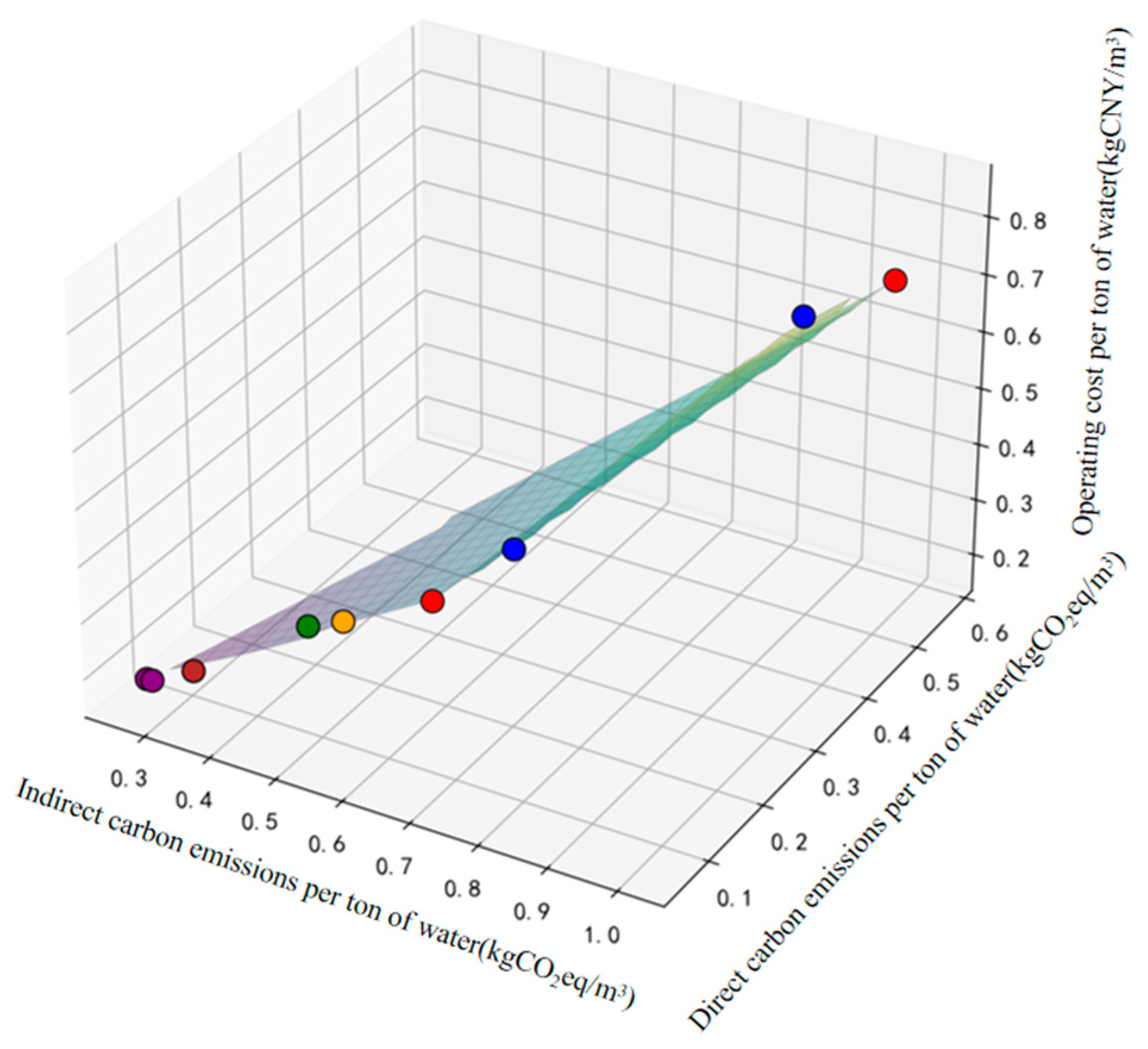

3.4. Multi-Objective Comparison and Selection Results

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lu, L.; Guest, J.S.; Peters, C.A.; Zhu, X.; Rau, G.H.; Ren, Z.J. Wastewater treatment for carbon capture and utilization. Nat. Sustain. 2018, 1, 750–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhao, G.; Jiao, Y.; Quan, B.; Lu, W.; Su, P.; Tang, Y.; Wang, J.; Wu, M.; Xiao, N.; et al. Critical analysis on the transformation and upgrading strategy of Chinese municipal wastewater treatment plants: Towards sustainable water remediation and zero carbon emissions. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 896, 165201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chon, K.; Ren, X.; Kou, Y.; Chae, K.; Piao, Y. Effects of beneficial microorganisms on nutrient removal and excess sludge production in an anaerobic-anoxic/oxic (A2O) process for municipal wastewater treatment. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 281, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, S.; Zhang, J.; Hu, B.; Zhao, J.; Yang, W.; Shi, B.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, J. Improving nutrients removal of Anaerobic-Anoxic-Oxic process via inhibiting partial anaerobic mixture with nitrite in side-stream tanks: Role of nitric oxide. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 382, 129207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Liu, J.; Wang, D.; Lu, M.; Fan, Y.; Ji, J.; Wu, J. Combined effects of carbon source and C/N ratio on the partial denitrification performance: Nitrite accumulation, denitrification kinetic and microbial transition. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 113343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, S.; Hu, Y.; Wei, R.; Yu, K.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, C.; Zhang, L. Carbon Footprint Drivers in China’s Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plants and Mitigation Opportunities through Electricity and Chemical Efficiency. Engineering 2025, 50, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Li, H.; Wu, B.; Meng, J. A nano-Al2O3 modified polypropylene hollow fiber membrane with enhanced biofilm formation in membrane aerated biofilm reactor application. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 112524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Wagner, B.M.; Carlson, A.L.; Yang, C.; Daigger, G.T. Recent progress using membrane aerated biofilm reactors for wastewater treatment. Water Sci. Technol. 2021, 84, 2131–2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.; Xu, S.; Yang, T.; Xiang, X.; Chai, C. Performance of MABR-coupled A2O process for municipal wastewater treatment. China Water Wastewater 2024, 40, 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Siagian, U.; Friatnasary, D.; Khoiruddin, K.; Reynard, R.; Qiu, G.; Ting, Y.; Wenten, I. Membrane-aerated biofilm reactor (MABR): Recent advances and challenges. Rev. Chem. Eng. 2024, 40, 93–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Daigger, G.T. The hybrid MABR process achieves intensified nitrogen removal while N2O emissions remain low. Water Res. 2023, 244, 120458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Yang, L.; Sun, J.; Wei, W.; Liu, Y.; Ni, B.J. Influences of longitudinal heterogeneity on nitrous oxide production from membrane-aerated biofilm reactor: A modeling perspective. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 10964–10973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Liu, T.; Hu, S.; Yuan, Z.; Dwyer, J.; Van Den Akker, B.; Lloyd, J.; Guo, J. Coupling partial nitritation, anammox and n-DAMO in a membrane aerated biofilm reactor for simultaneous dissolved methane and nitrogen removal. Water Res. 2024, 255, 121511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweetapple, C.; Fu, G.; Butler, D. Multi-objective optimisation of wastewater treatment plant control to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Water Res. 2014, 55, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Martínez, V.M.; Martínez-Frutos, J.; Hontoria, E.; Hernández-Fernández, F.J.; Egea, J.A. Multiplicity of solutions in model-based multiobjective optimization of wastewater treatment plants. Optim. Eng. 2021, 22, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, J.; Jia, X.; Liu, L.; Wang, J.; Abbasi, H.N.; Guo, Z.; Chen, Y.; Geng, H.; et al. Modeling and optimizing of an actual municipal sewage plant: A comparison of diverse multi-objective optimization methods. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 328, 116924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Zhao, W.; Wu, N.; Wu, D. Multi-objective optimization: A method for selecting the optimal solution from Pareto non-inferior solutions. Expert Syst. Appl. 2017, 74, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béraud, B.; Steyer, J.P.; Lemoine, C.; Latrille, E.; Manic, G.; Printemps-Vacquier, C. Towards a global multi objective optimization of wastewater treatment plant based on modeling and genetic algorithms. Water Sci. Technol. 2007, 56, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muschalla, D. Optimization of integrated urban wastewater systems using multi-objective evolution strategies. Urban Water J. 2008, 5, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Yang, E.; Xu, C.; Zhang, T.; Xu, R.; Fu, B.; Feng, Q.; Fang, F.; Luo, J. Model-based strategy for nitrogen removal enhancement in full-scale wastewater treatment plants by GPS-X integrated with response surface methodology. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 769, 144851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasim, N.A. The design for wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) with GPS-X modelling. Cogent Eng. 2020, 7, 1723782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; Li, S.; Liu, Y.; Mao, S.; Tian, T.; Ma, X.; Li, B.; Qiu, Y. Multi-objective optimization based on simulation integrated pareto analysis to achieve low-carbon and economical operation of a wastewater treatment plant. Water 2024, 16, 995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 18918-2002; Discharge Standard of Pollutants for Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plant. China Environmental Science Press: Beijing, China, 2002.

- GB 3838-2002; Environmental Quality Standards for Surface Water. China Environmental Science Press: Beijing, China, 2002.

- Hu, Y.; He, Y.; Song, N.; Niu, J.; Yang, C.; Qiu, L. Study on the Effect of MABR-AO Coupling Process on the Treatment of Low C/N Township Domestic Sewage. Environ. Impact Assess. 2024, 46, 69–73, 77. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Mu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wu, Y.; Xue, X.; Cao, Z.; Li, J. Pilot-scale verification study of the MABR process for municipal wastewater treatment. Chin. J. Environ. Eng. 2025, 19, 2645–2655. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, J.; Jiang, H.; Qiu, L.; Yang, J.; Zhang, H.; Liang, H.; Ni, B.J. Synergistic suppression of nitrous oxide and residual nitrate in DNRA-enhanced MABR-PN/A hybrid systems. Water Res. 2025, 286, 124245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Mao, S.; Zhao, W.; Chen, Y.; Cao, X.; Tian, T.; Ma, X.; Li, B.; Qiu, Y. Multi-objective comparison of conventional and emerging wastewater treatment processes based on simulation to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2025, 19, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, F.; Li, B.; Xing, M.; Wang, Q.; Hu, L.; Wang, S. Surface modification of PVDF hollow fiber membrane and its application in membrane aerated biofilm reactor (MABR). Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 140, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Han, X.; Lin, Y.; Jin, Y.; Song, X. Insights into partial nitrification in a membrane-aerated biofilm reactor (MABR): Performance, microbial characteristics, and mechanisms. ACS EST Eng. 2025, 5, 2555–2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uri-Carreño, N.; Nielsen, P.H.; Gernaey, K.V.; Domingo-Félez, C.; Flores-Alsina, X. Nitrous oxide emissions from two full-scale membrane-aerated biofilm reactors. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 908, 168030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Bao, D.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, W.; Zhang, C.; Yang, H.; Ru, Q.; Wang, Y.-f.; Ma, H.; Zhu, E.; et al. Development and Application of Membrane Aerated Biofilm Reactor (MABR)—A Review. Water 2023, 15, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamais, D.; Noutsopoulos, C.; Dimopoulou, A.; Stasinakis, A.; Lekkas, T.D. Wastewater treatment process impact on energy savings and greenhouse gas emissions. Water Sci. Technol. 2014, 71, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Yan, G.; Wang, H.; Shi, L.; Zhang, Y.; Ling, Y.; Wei, Y.; Wang, H.; Dong, W.; Chang, Y.; et al. Denitrification enhanced by composite carbon sources in AAO-biofilter: Efficiency and metagenomics research. J. Environ. Sci. 2025, 150, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Wang, C.; Lu, C.; Zhao, W.; Liu, C.; Chen, D.; Jiang, B.; Fan, X.; Zhao, Z.; Chen, Y.; et al. Carbon emissions from rural wastewater treatment using the anoxic-anaerobic-oxic membrane bioreactor process. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 510, 145640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Feng, M.; Zheng, S.; Zhao, W.; Xu, X.; Yu, X. The membrane aerated biofilm reactor for nitrogen removal of wastewater treatment: Principles, performances, and nitrous oxide emissions. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 460, 141693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, X.; Tian, Y.; Gan, Y.; Ji, J. Quantifying urban wastewater treatment sector’s greenhouse gas emissions using a hybrid life cycle analysis method—An application on Shenzhen city in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 745, 141176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinh, C.T.; Riya, S.; Hosomi, M.; Terada, A. Identification of hotspots for NO and N2O production and consumption in counter- and co-diffusion biofilms for simultaneous nitrification and denitrification. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 245, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, J.; Zhu, Y.; Xu, S.; Xu, B.; Cao, L.; Huang, X. Effects of process parameters on the performance of membrane-aerated biofilm reactors in wastewater treatment. Environ. Eng. 2025, 43, 95–103. [Google Scholar]

- He, H.; Carlson, A.L.; Wagner, B.; Yang, C.; Cao, Y.; Uzair, M.D.; Daigger, G.T. An update on hybrid membrane aerated biofilm reactor technology. Water Environ. Res. 2025, 97, e70065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Perez-Calleja, P.; Li, M.; Nerenberg, R. Effect of predation on the mechanical properties and detachment of MABR biofilms. Water Res. 2020, 186, 116289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Water Quality Indicators | Influent (mg/L) | Effluent (mg/L) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H | M | L | A | IV | |

| COD | 1000 | 500 | 250 | 50 | 30 |

| BOD | 400 | 220 | 110 | 10 | 10 |

| SS | 350 | 200 | 100 | 10 | 10 |

| TN | 85 | 40 | 20 | 15 | 10 |

| NH4+-N | 64 | 30 | 15 | 5 | 1.5 |

| TP | 15 | 8 | 4 | 0.5 | 0.3 |

| Process | Facilities | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| AAO | Anaerobic tank | 1000 | m3 |

| Anoxic tank | 1000 | m3 | |

| Aerobic tank | 1000 | m3 | |

| DO | 1.0 [25,27] | mg/L | |

| AAO-MABR (Anoxic) | Anaerobic tank | 1000 | m3 |

| MABR | 1000 | m3 | |

| DO(MABR) | 0.2 | mgO2/L | |

| Aerobic tank | 1000 | m3 | |

| DO | 1.0 [25,27] | mgO2/L | |

| Carrier outer diameter | 0.001 | m | |

| Carrier length | 2.0 | m | |

| Liquid film thickness | 0.05 | mm | |

| AAO-MABR (Aerobic) | Anaerobic tank | 1000 | m3 |

| Anoxic tank | 1000 | m3 | |

| MABR | 1000 | m3 | |

| DO(MABR) | 2.0 [25,27] | mg/L | |

| Carrier outer diameter | 0.001 | m | |

| Carrier length | 2.0 | m | |

| Liquid film thickness | 0.005 | mm |

| Influent Concentration | Effluent Standard | Optimal Process |

|---|---|---|

| High Influent Concentration | Grade I-A | AAO-MABR(Aerobic)\AAO-MABR(Anoxic) |

| High Influent Concentration | Class IV | AAO-MABR(Aerobic)\AAO-MABR(Anoxic) |

| Medium Influent Concentration | Grade I-A | AAO-MABR(Anoxic) |

| Medium Influent Concentration | Class IV | AAO-MABR(Anoxic) |

| Low Influent Concentration | Grade I-A | AAO-MABR(Aerobic)\AAO-MABR(Anoxic) |

| Low Influent Concentration | Class IV | AAO-MABR(Anoxic) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sun, C.; Liu, M.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, H.; Li, B.; Qiu, Y. Low-Carbon Operation Strategies for Membrane-Aerated Biofilm Reactor Through Process Simulation and Multi-Objective Optimization. Water 2026, 18, 150. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020150

Sun C, Liu M, Chen Y, Zhu H, Li B, Qiu Y. Low-Carbon Operation Strategies for Membrane-Aerated Biofilm Reactor Through Process Simulation and Multi-Objective Optimization. Water. 2026; 18(2):150. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020150

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Chaoyu, Mengmeng Liu, Yasong Chen, Hongying Zhu, Bing Li, and Yong Qiu. 2026. "Low-Carbon Operation Strategies for Membrane-Aerated Biofilm Reactor Through Process Simulation and Multi-Objective Optimization" Water 18, no. 2: 150. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020150

APA StyleSun, C., Liu, M., Chen, Y., Zhu, H., Li, B., & Qiu, Y. (2026). Low-Carbon Operation Strategies for Membrane-Aerated Biofilm Reactor Through Process Simulation and Multi-Objective Optimization. Water, 18(2), 150. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020150