1. Introduction

The equilibrium of sedimentary processes and the dynamic characteristics of mountain rivers are of critical importance for the maintenance of favourable ecological and morphological conditions [

1,

2]. Alpine rivers function as conduits, facilitating the transfer of sediment production within the Alpine region to downstream rivers [

3]. The disruption of this continuity by dams, weirs, and other hydraulic structures can lead to sediment deficits, channel incision and habitat degradation [

4,

5]. Therefore, sustainable sediment management strategies are essential to mitigate these impacts and ensure both geomorphological stability and ecological integrity in fluvial systems [

6,

7]. However, the continuity of the bedload has become a pivotal consideration in numerous water management and hydraulic engineering initiatives [

8,

9].

The possibilities for monitoring the bedload transport process have improved significantly over the last two decades, particularly through the development of surrogate measurement techniques [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21], many years of experience [

13,

15,

19,

20,

22,

23,

24], and further development in the use of direct measuring devices and the integrative approach of combining direct and indirect methods [

11,

13,

18,

22,

25,

26,

27]. At the same time, there was a significant increase in the application of radio frequency identification (RFID) technology in geoscience [

19]. In their review, Le Breton et al. [

19] emphasise the diverse applications of RFID, including the monitoring of slope movements with centimetre-level accuracy and the detection of displacement thresholds in unstable rocks. However, the most advanced application to date is the study of bedload transport in rivers, with over 30,000 RFID tracers being monitored in gravel-bed rivers as in our study across the globe [

15].

RFID is a communication system that uses electromagnetic waves, specifically radio waves. In its most basic configuration, an RFID system consists of three primary components: the RFID target, called the ‘tag’ (transponders), an RFID reader (interrogator), and a host computer [

15]. Both active and passive RFID systems are commonly used in scientific research, though this work focuses on passive RFID [

15]. In such systems, the reader emits a radio frequency wave that is received by the RFID tag. The tag then modulates the signal to encode information and reflects the modified wave back to the reader [

20]. The signal can be collected using either fixed or mobile readers [

19].

The most commonly used passive RFID tags in sediment transport studies are waterproof, glass-encapsulated, low-frequency (134.2 kHz) tags with a length ranging from 12–32 mm [

28,

29,

30]. These tags are typically embedded in natural rocks by drilling, although artificial rocks (concrete) can also be used. Once tagged, RFID tracers are placed in river channels and can be transported by one or more flood events. Their movement is monitored after a period of time using a mobile antenna and positioning system or a fixed antenna on a river cross-section [

24]. Mobile readers are available as a pre-configured plug-and-play system, offering flexibility and the ability to scan large areas. Fixed antennas allow the continuous monitoring of tags within their reading range. However, their installation requires the establishment and maintenance of a permanent infrastructure, and each antenna can only cover a limited area.

Some of the key advantages that have contributed to the application of RFID tags in sediment transport studies include their low cost, durability, and compact size; the fact that there is no need for a power supply in the particle; and their consistent results under harsh environmental conditions [

15,

19,

28].

The RFID method allows the Eulerian observation of individual sediment particles. It is based on the concept introduced by Einstein [

31], which describes bedload transport as a stochastic process involving individual particle movements and characterised by sequences of step lengths and rest periods following an exponential distribution [

32,

33]. The most common application of RFID tags in fluvial sediment transport is the study of grain dispersion caused by flow events along river reaches [

19]. By recording the positions of individual particles before and after the event, transport lengths, transport velocities, resting times, and deposition characteristics can be determined [

34,

35,

36,

37]. Le Breton et al. [

19] provide a comprehensive overview of existing RFID studies, categorising them into key research areas. These include studies on the controlling factors of bedload dispersion, such as the relationship with hydraulic predictors, the influence of grain size effects [

3,

38], and the impact of morphological factors [

39].

RFID tracers have been shown to achieve high recovery rates across a range of channel types, with some studies reporting up to 96% success in sand- gravel- and boulder-bed streams [

40,

41]. This suggests that the method is highly robust. The integration of active tracers with accelerometers provides additional information about initiation timing, movement frequencies, step lengths, and rest periods. This, in turn, enables probabilistic insights into transport processes that extend beyond what is possible with passive systems [

40,

42]. Large field deployments are instrumental in quantifying the thickness of the active layer and elucidating the role of channel morphology, grain-size distribution, and hydrological regime in governing mobility, transport distances, and size-dependent efficiency [

40,

43,

44]. In glaciated basins, the recovery rates exhibit significant variability (19–97%), underscoring the dynamic coupling among discharge, bedload transport, and meltwater. This dynamic coupling motivates the necessity of long-distance and long-term monitoring [

45,

46]. Emerging applications of stationary antennas, though less prevalent, demonstrate their effectiveness in specific configurations and complement mobile surveys [

15].

Studies using fixed installed antennas typically focus on defining the downstream boundary of the study area to maximise recovery rates by accounting for tracers that have left the surveyed river section [

28,

47]. Schneider et al. [

48] compared two configurations of stationary antennas: ‘pass over’ (horizontal passage) and ‘pass through’ (vertical passage). Larger transponders (32 mm) had higher detection rates than smaller ones (23 mm). ‘Pass over’ antennas performed better with close proximity, while ‘pass through’ antennas provided uniform detection across their height. The study highlighted the sensitivity of antennas to environmental factors and recommended extensive field tests to determine the optimal configuration.

The influence of low-water dams on the dynamics of coarse sediment transport is analysed in real time using a stationary RFID antenna by Casserly et al. [

24]. Their results show that up to 43% of the deployed tracers vacated the impoundment during two high-flow events, with the stationary antenna detecting 38% of the tracers. This provided real-time data on specific discharge thresholds for sediment movement, highlighting the potential of stationary antennas for the real-time monitoring of sediment transport.

Mao et al. [

20] investigated coarse sediment movement in the Saldur River, Italian Alps, using four stationary antennas to monitor 629 passive integrated transponder (PIT) tagged clasts. They found a weak correlation between the sediment size and discharge, highlighting the importance of the flow history. The study revealed size-selective transport and the impact of bedform spacing on particle displacement, with an inverse relationship between the flight distance and grain size. They proposed using the effective gradient value to improve bedload transport predictions.

In summary, both mobile and stationary antennas are effective in tracking sediment transport, though their applications and insights are complementary and distinguish them from one another. Mobile antennas consistently achieve high recovery rates and provide valuable data across diverse river regimes. They are effective in monitoring sediment transport dynamics and offer flexibility for different geographical locations and sediment types. Stationary antennas, while less commonly used, are useful in specific applications. The literature highlights the importance of the antenna configuration, environmental sensitivity, and real-time monitoring capabilities. These studies reveal complex interactions between the sediment size, discharge, and flow history, offering detailed insights into sediment transport dynamics. Overall, both methods contribute significantly to understanding sediment transport, with mobile antennas providing broad applicability and stationary antennas offering precise, real-time data in targeted scenarios. Tracer measurements also provide transient virtual velocity data. Klösch and Habersack [

49] developed the

graVel programme, which calculates the unsteady virtual velocity from tracer data using linear and non-linear formulas. While significant progress has been made in understanding bedload transport processes, analysing tracer data offers further potential for advancing this field [

49].

This study presents tracer studies using stationary RFID antennas to record and analyse bedload transport processes in alpine catchment areas. Two case studies demonstrate the application of this technology. Passive low-frequency passive integrated transponders (PITs) are embedded in natural clasts. In the present study, the range of these tags was from 12 × 2 to 32 × 4 mm. In consideration of dimensional parameters, this phenomenon engenders a pragmatic limitation on the viability of tracer production, confining it to a range that is constrained by the size of gravel. Consequently, RFID-based observations are more effective in characterising the mobility and virtual velocities of tagged gravel fractions than they are in characterising the full bedload size spectrum or an instantaneous total bedload transport rate. Our interpretation is consistent with the Einstein framework [

31], which conceptualises bedload as a stochastic sequence of particle steps and rests. Stationary antennas provide time-synchronised records of individual tracer passages, from which virtual velocities are derived for the tagged size classes. In the Strobler-Weißenbach case study, two stationary RFID antennas were installed at a single location to optimise retention barrier management [

50]. This setup enables the continuous monitoring of bedload movements to support informed decisions in flood protection and sediment management.

At the Urslau site, the RFID technology complements an integrative bedload measurement system that has been in place since 2011 [

51]. This system provides continuous and long-term data on the transport processes in the stream. The additional equipment with a total of seven stationary RFID antennas at three strategically selected locations opens up extended possibilities for answering fundamental questions regarding the origin of the transported material during individual flow events, how the transport velocities depend on the intensity of such events, and the time that particles remain within the system.

This study aims to detail the applied methodology, demonstrate its analytical capabilities, and present initial results on selective transport processes and particle velocities. It contributes to advancing the instrument-based monitoring of bedload transport in stream systems by using stationary antennas and 1612 RFID-tagged stones. The first key aspect of this study is the development and installation of a permanent tracer monitoring system in alpine streams (i). To achieve this, stationary antennas were increasingly used to reduce the need for complex mobile searches, as suggested by Mao et al. [

20]. These installations allow the evaluation of the detection range and detection rate of fixed systems in alpine rivers (ii) and provide valuable insights into their effectiveness. Furthermore, the study investigates which processes can be monitored using both mobile and stationary antennas (iii). By combining these methods, it is possible to gain a comprehensive understanding of sediment transport dynamics. Special attention is given to the measurement of particle velocities in natural environments, which is made possible by the use of stationary antennas (iv). These measurements are essential to improve the understanding of transport velocities and their implications for sediment and flood management.

Accordingly, the objective is to underscore the particular capacity of multi-stationary RFID antenna systems for short- and long-distance bedload velocity monitoring. It is demonstrated that these systems facilitate autonomous, long-term tracer measurements with minimal personnel effort.

2. Materials and Methods

The two case study areas are both located in Austria in the province of Salzburg. Specifically, they are the catchment areas of the Urslau and the Strobler-Weißenbach (

Figure 1).

2.1. Case Study Areas

The Urslau stream rises approximately 1800 m above sea level (a.s.l.) and discharges after a total flow length of 21.3 km into the Saalach River (716 m a.s.l.). The total catchment area of the Urslau stream is 122 km

2. Geologically, the Urslau catchment is characterised by two geologically different zones: the greywacke zone is in the south of the catchment area, and the Limestone Alps are in the north. The Urslau has a ‘moderate nival’ runoff regime, which is defined by the period of highest runoff in May and June. Intense snowmelt periods and heavy rainfall events during summer are characteristic of the watershed [

52].

Table 1 summarises the hydrological and morphological parameters of the catchment area.

The upper section of the Urslau is defined by a very steep channel gradient (S = 0.27). Moving downstream, the river transitions from this steep section to flow across extensive alluvial deposits. In the middle reach, located approximately 17 km upstream of its confluence with the Saalach, where the RFID analyses of this paper are performed, the Urslau adopts the characteristics of a partially confined, straight, single-thread alluvial channel. In this section, the stream width varies between 7 m and 10 m, with an average bed slope gradient of 0.028. Additionally, three significant tributaries join the Urslau within this middle reach, contributing substantial sediment loads due to active erosion and hillslope processes. Notably, in 2011, an integrative bedload monitoring station was established 10 km upstream of the Saalach confluence [

51,

53]. Here, the hydrographic service of Salzburg provided discharge data with a 15 min resolution. The catchment size upstream of the station is 56 km

2.

The majority of the catchment area of the Strobler-Weißenbach is located in the Eastern Alpine and Central Alpine Permo-Mesozoic; only a small part of it lies in the area of the Holocene and Pleistocene sediments and the flysch zone. In these areas there are three predominant rock types: banked Dachstein limestone, Wetterstein dolomite, and Ramsau dolomite. The highest point of the catchment area is at 2027 m a.s.l. (Gamsfeld) and the lowest point is at 529 m a.s.l. at the mouth. Thus, the Strobler-Weißenbach has an average gradient of 2.8% on its way into the valley. The source of the Strobler-Weißenbach can be found between the Rinnkogel (1828 m) and the Schoberstein mountain range. The mouth of the Strobler-Weißenbach into the Ischler Ache is located, after approximately 9.5 km of flow, in Upper Austria at an altitude of 529 m a.s.l. near the Salzburg border.

The nivo-pluvial regime exhibits a pronounced discharge maximum in the months of April and May, a period marked by snowmelt. As illustrated in

Table 1, the primary statistical discharge parameters for the Strobler-Weißenbach are presented, among other relevant data. The measuring station operated by the hydrographic service of Salzburg is situated at river kilometre 4 of the Strobler-Weißenbach. This station is designed for the observation of the water level, water quantity, and water temperature, with a temporal resolution of 15 min [

50].

2.2. Methodology

Mobile RFID-antennas are consistent with the Lagrange approach, rendering them particularly well-suited for the analysis of spatial patterns in transport, deposition, and remobilization, in addition to individual distances (

) and individual time

. In addition, the event-related mean particle velocities

must be considered.

No installation in the river is required. They are also flexible along accessible sections of the river and are suitable for pre/post event comparisons. Disadvantages include the discrete time resolution, the variable detection probability and the high personnel costs per inspection. The discrete time resolution results from the fact that events are only recorded on a random basis and holistically by the preceding and subsequent inspections. The variable detection probability depends on the depth, orientation and sediment cover. Added to this are the high personnel costs per inspection, including safety measures and restrictions due to the existing flow.

In contrast, stationary RFID antennas adopt an Eulerian approach, a method that has proven advantageous in scenarios where continuous event dynamics, movement initiation, and throughput at the cross-section are required in real time with known distance. The calculation of average particle velocity between stationary antennas (

) is achieved by determining the known distance (

) distance to elapsed time (

), expressed as

The estimation of section velocities can be facilitated by employing two or more antennas:

The calculation of section velocities () is further facilitated by the utilisation of two or more antennas were (the distance between two antennas) and and correspond to the time of detection on the respective stationary antenna. The strengths of this method lie in its high temporal resolution and minimal personnel requirements. The aforementioned factors are counterbalanced by the expenses associated with installation, the necessity of a constant and secure power supply, the requirement for a mandatory inspection and maintenance log, and the potential risks of system failure. For flood resilience, a robust installation that is resistant to floating debris and blockages is essential; a stable internet connection enables monitoring, alerting and ongoing data backup (with buffer memory and emergency power as backup). In practice, mobile recording is used when the focus is on detailed spatial information and flexibility; stationary recording is used when events are to be recorded continuously and reliably. The optimal solution is often a combination of both approaches in order to make complementary use of spatial and temporal resolution.

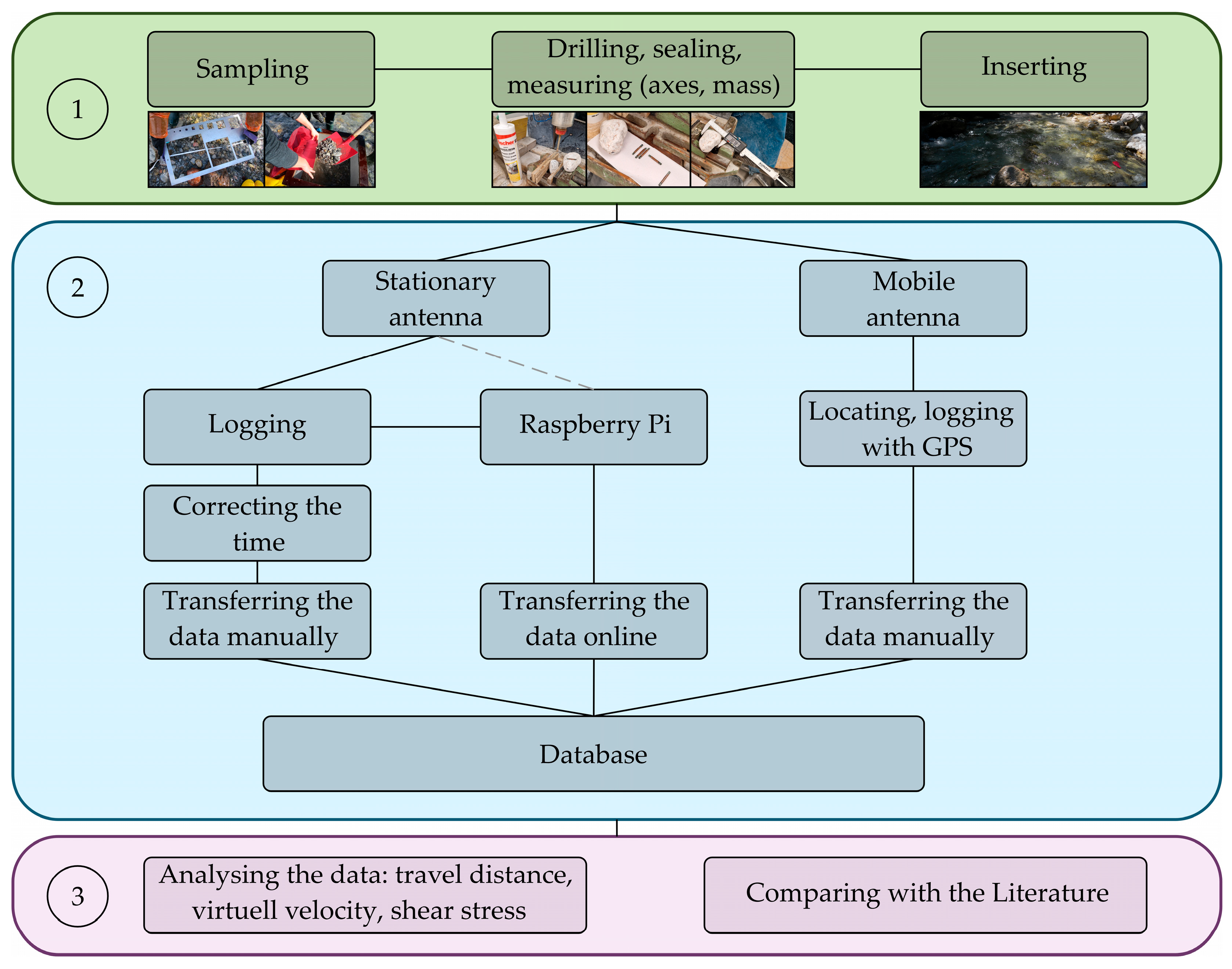

The workflow for tracer preparation, data collection, and analysis was divided into three main stages, as illustrated in

Figure 2.

In the first stage, representative sediment particles were sampled from the study site. The tracer material was collected directly at gravel bars and from the river surface at the future seeding site. At both study sites, different grain fractions, distributed over the grading curve of the individual stream, were chosen. Each selected stone was drilled, tagged with an RFID-PIT tag, sealed, and measured to determine its major axes and mass. The RFID-PIT tags used in this study range from 32 mm × 4 mm (for the best read range) to 12 mm × 2 mm produced by Texas Instruments and retailed by Oregon RFID located in Portland, OR, USA [

54]. After preparation, the tagged stones were placed in the stream at predefined locations to monitor their subsequent transport during bedload transport events. The rock types that are suitable for RFID-tagged tracers have been primarily carbonate rocks, with a small proportion of silicified carbonate. However, the material from the Grauwacke zone is not suitable for tracer production due to its propensity to break during drilling. The average weight of the stone is reduced by 0.5 g after the RFID tag has been installed using a 4 mm drill bit, and by 1.8 g after installation with a 6 mm drill bit, in comparison to the weight of the stone without the tag. This is particularly relevant for smaller grain sizes, as a 20 g stone experiences a mass loss of approximately 2.5 percent when utilising a 4-millimeter drill bit. For stones with a mass of 1 kg, the mass loss resulting from tagging with a 6 mm drill bit is 0.18 percent. This negligible loss has no substantial effect on the density of the stones.

In the second phase, data were collected using both stationary and mobile RFID antennas. The stationary antennas, which are the focus of this paper, were permanently installed at the field site to provide the continuous detection of passing tracers. Data were initially stored on a local logger, with timestamps corrected to ensure synchronisation between antennas. These data were then transferred to a central database, either manually or automatically via Raspberry Pi 4 (Pencoed, UK). Mobile antennas, on the other hand, were used during field campaigns to locate and record tracer positions using real-time kinematic global navigation satellite system RTK GNSS. While mobile antennas are mentioned here for completeness, they are not the focus of this study. Data from both systems were merged into a central database, which served as the basis for further analysis. In the third phase, the collected dataset was analysed to derive transport distances, transport velocities, and the discharge associated with the detected transport events. These results were compared with values reported in the literature to assess the comparability of the observed sediment transport processes and to validate the applied RFID-based monitoring approach.

A passive RFID tracer consists of a microelectronic chip that stores a small amount of data (its unique identifier), a capacitor, and an antenna for sending and receiving signals [

28,

55]. These tracers do not have their own energy source, which has benefits for both their size and lifetime. The tag receives the energy it needs to transmit its identifier via inductive coupling with the reader’s antenna [

40,

56,

57]. Depending on the setup, this field can cover a range of up to 1 m [

28,

58]. Thereby, there are two alternating states of the RFID reader, the charge sequence and the listen sequence. By default, both sequences are active for 50 ms. If a tag is within this electromagnetic field, the capacitor is charged (charge sequence) and releases enough energy for the tag to transmit its unique identifier back to the receiver via a radio signal in the listen sequence. Using a mobile antenna, it will emit an acoustic signal upon detection. The detection record is then stored in a database (for both stationary and mobile antennas) and the tag’s unique identifier is transmitted to a Bluetooth-connected device (e.g. common smart phone or tablet) [

57].

Chapuis et al. [

28] recommend the use of stationary antennas at the end of the study reach to maximise recovery rates by accounting for tracers that have left the surveyed river section. At the Strobler-Weißenbach, we installed two stationary antennas within a distance of ~25 m to measure the bedload transport velocity and for redundancy reasons [

20]. With the information gained, we installed seven antennas at three locations along the Urslau stream to measure the bedload transport velocity automatically.

This monitoring concept enabled us to gain information about the transport velocity of the bedload during transport events. To determine the antenna’s optimum detection-range, laboratory tests were carried out.

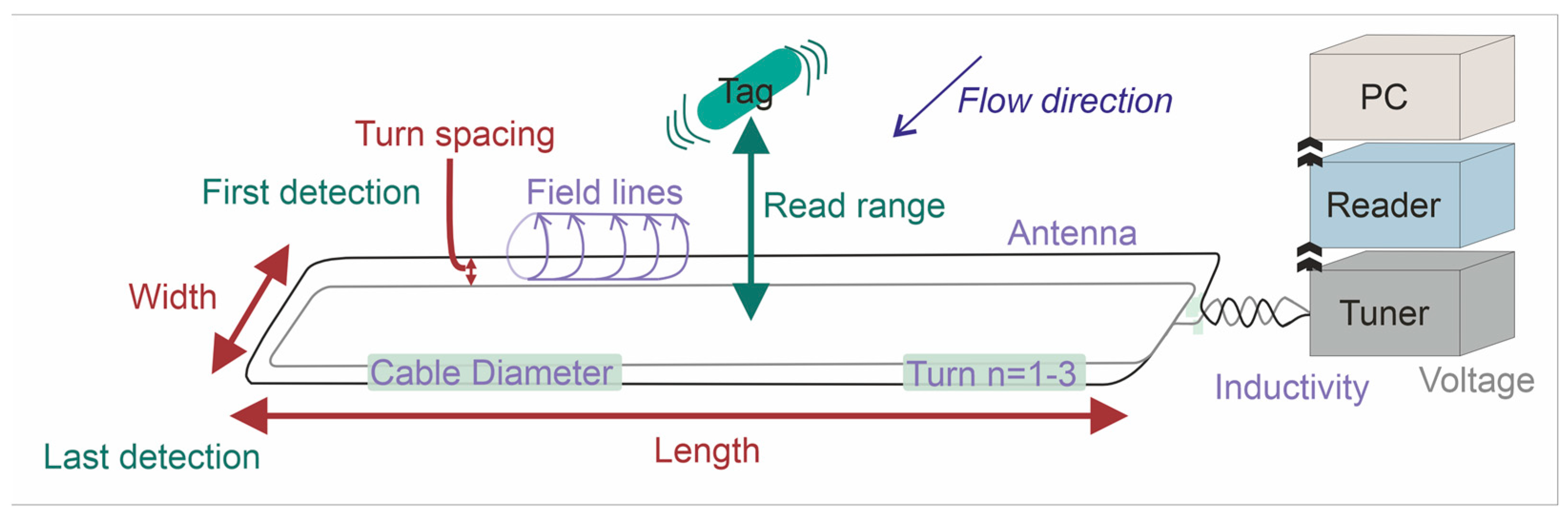

2.3. Laboratory Experiment

In a laboratory experiment, a total of 57 tests were conducted to examine the effect of various parameters on the read range of the stationary antenna. The geometry of the antenna was varied in terms of the length (4–8 m), width (0.1–2.5 m), number of turns (1–3), and turn spacing (0–0.25 m). The surface area of the wire ranged from 1.5 mm

2 to 6 mm

2, with the number of strands varying from 18 to 1559. Both copper and steel cables were tested. The electrical and hardware variables included an input voltage range of 12–21 V, with power supplied by either a battery or an FEAS 12V AC-to-DC adapter made in Ahrensburg, Germany. Reader devices were manufactured by Oregon RFID located in Portland, OR, USA, with configurations including single-reader and multiplex-reader setups (see

Figure 3).

The optimal configuration was determined to be an 8-metre antenna with a width of 0.5 m, two turns, no spacing between turns, a surface area of 6 mm

2, and an input voltage of 19.1 V. The inductance for this configuration was measured at 55.34 µH. This setup achieved a read range of 0.54 m in the lab. A summary of the tested parameters and the best results are provided in

Table 2.

2.4. Field Experiment

As part of the field experiment, the antenna configuration with the best laboratory result was tested on site prior to installation. The final version of the antenna was identical to the one used in the lab test, with the exception of the power supply, which, due to power supply restrictions, was modified to 12 V. This configuration enabled a maximum detection range of 0.72 m. Determining this maximum value was essential for making decisions about the potential installation depth and the extent of sediment or concrete coverage.

2.5. Installations in the Field and Stationary Antennas

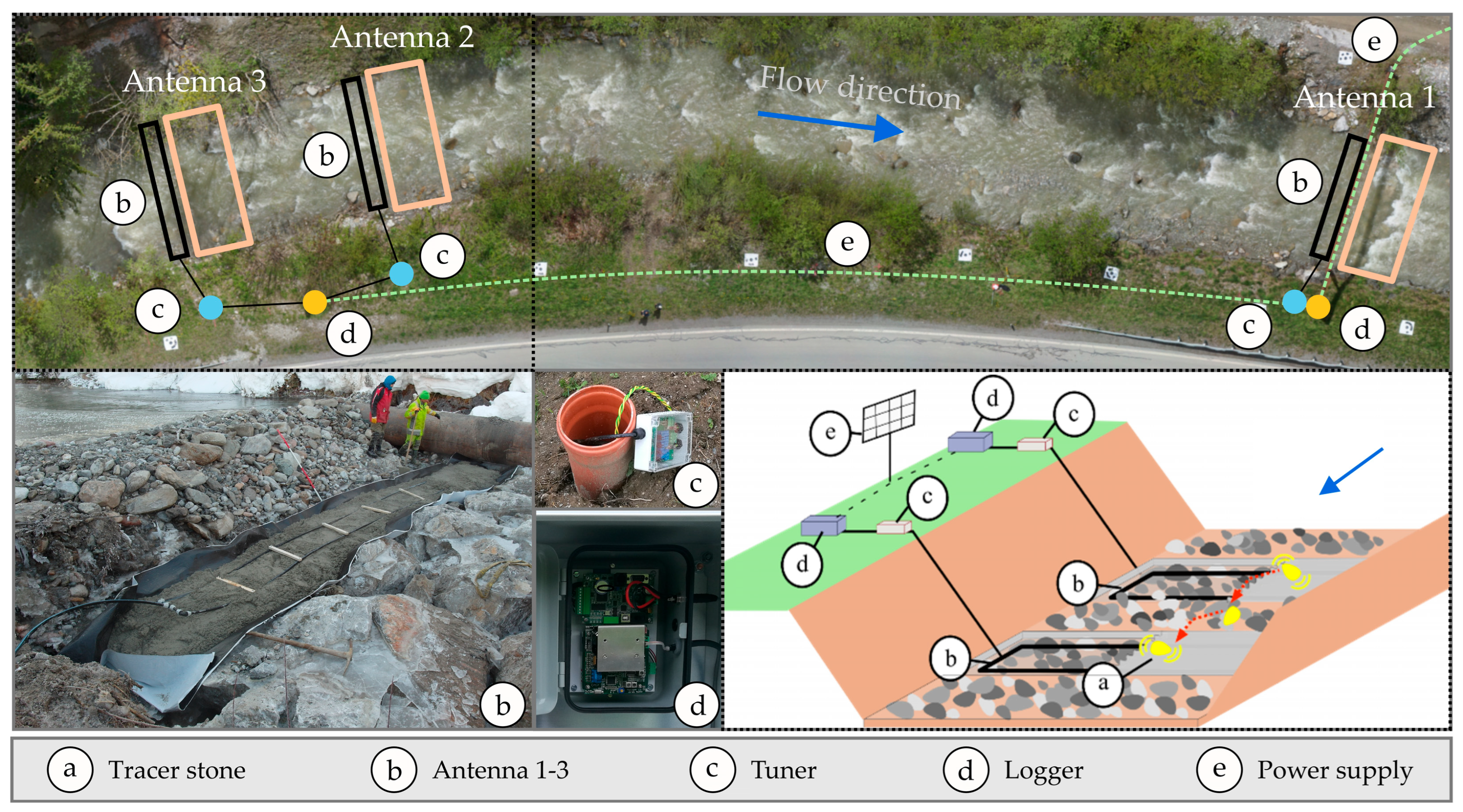

As shown in the schematic illustration in

Figure 4 (bottom right), a minimum of two antennas were consistently installed in the field. The configuration of the field setup includes the following elements: (b) an antenna wire that is installed in the form of a loop in the riverbed and encased in concrete, (c) a tuner box that operates and calibrates the antenna, (d) a reader that records the dedicated tracer stones and controls the antenna, and (e) a power supply that is either solar (in orange) or grid-powered (green dotted line). All antennas were encased in concrete with a minimum coverage of 20 cm to protect them from abrasion and ensure sufficient range to detect the RFID tags. Steel was deliberately avoided to prevent interference (reduction in read range). A layer of stone (bedding) was always placed downstream of the antenna to stabilise the profile and prevent deformation in the area of the antenna (

Figure 4, bottom left). The redundancy of the tracer stone recording ensures the reliability of the system, while the transport speed between the various antennas can be measured.

At the Strobler-Weißenbach case study site, a stationary antenna was installed at a single location (compare with

Figure 1). The setup in Strobl consists of two antennas spaced 24 m apart.

At the Urslau site, the monitoring programme includes three antenna locations along the course of the stream. The numbering of the locations and antennas follows the upstream direction.

Antenna location 1 is situated at the integrative bedload measuring station and consists of three individual antennas (U1, U2, U3). The distances between them are as follows: U1–U2 = 68.3 m, U2–U3 = 18.5 m, and U1–U3 = 87.7 m. Antenna location 2 is positioned downstream of the Handlergraben tributary and includes two antennas (U4, U5) spaced 13.8 m apart. The distance between the two locations i.e., antennas U3 and U4 is 1477.54 m. Antenna location 3 is situated downstream of the Pirnbach tributary and again consists of two antennas (U6, U7), with a spacing of 14.43 m. The site is located 2844.94 m upstream of antenna location 2 (distance between antennas U5 and U7).

2.6. Time Syncronisation

Precise timekeeping was imperative, given that each antenna was equipped with its own tuner and data logger. At the outset and at repeated intervals throughout the study, a comparison was made between each logger’s clock and an atomic time reference. When necessary, the logger timestamps were corrected. Clock drift was characterised by the implementation of linear functions to model the offset between the logger time and the atomic reference. This approach entailed the execution of repeated comparative measurements, from which the resulting corrections were applied to all recorded timestamps. These calibrations were conducted multiple times per year and yielded a relative timing accuracy of approximately 80 s between two readers deployed at the same RFID site. Since 2020, time synchronisation using RFID has been ensured by the real-time reading of the Raspberry Pi during data output from the RFID module, followed by the assignment of a timestamp to each output line. This process involves an extremely low delay of between 100 and 200 milliseconds. Since two antennas are connected to a Raspberry Pi, they receive the same timestamp as the Raspberry Pi. The Raspberry Pi is continuously connected to the internet, and synchronisation is carried out via a time server. This ensures that antennas connected to a Raspberry Pi receive the same time in the millisecond range.

2.7. AI Usage

The development and refinement of Python 3.12.11 scripts for data processing and analysis was facilitated by the utilisation of generative artificial intelligence tools. The employment of an AI tool was undertaken to suggest code structures, optimise existing routines, and support debugging. The authors have meticulously reviewed, tested, and validated all generated code.

3. Results

3.1. Stone Geometry and Recovery Rates

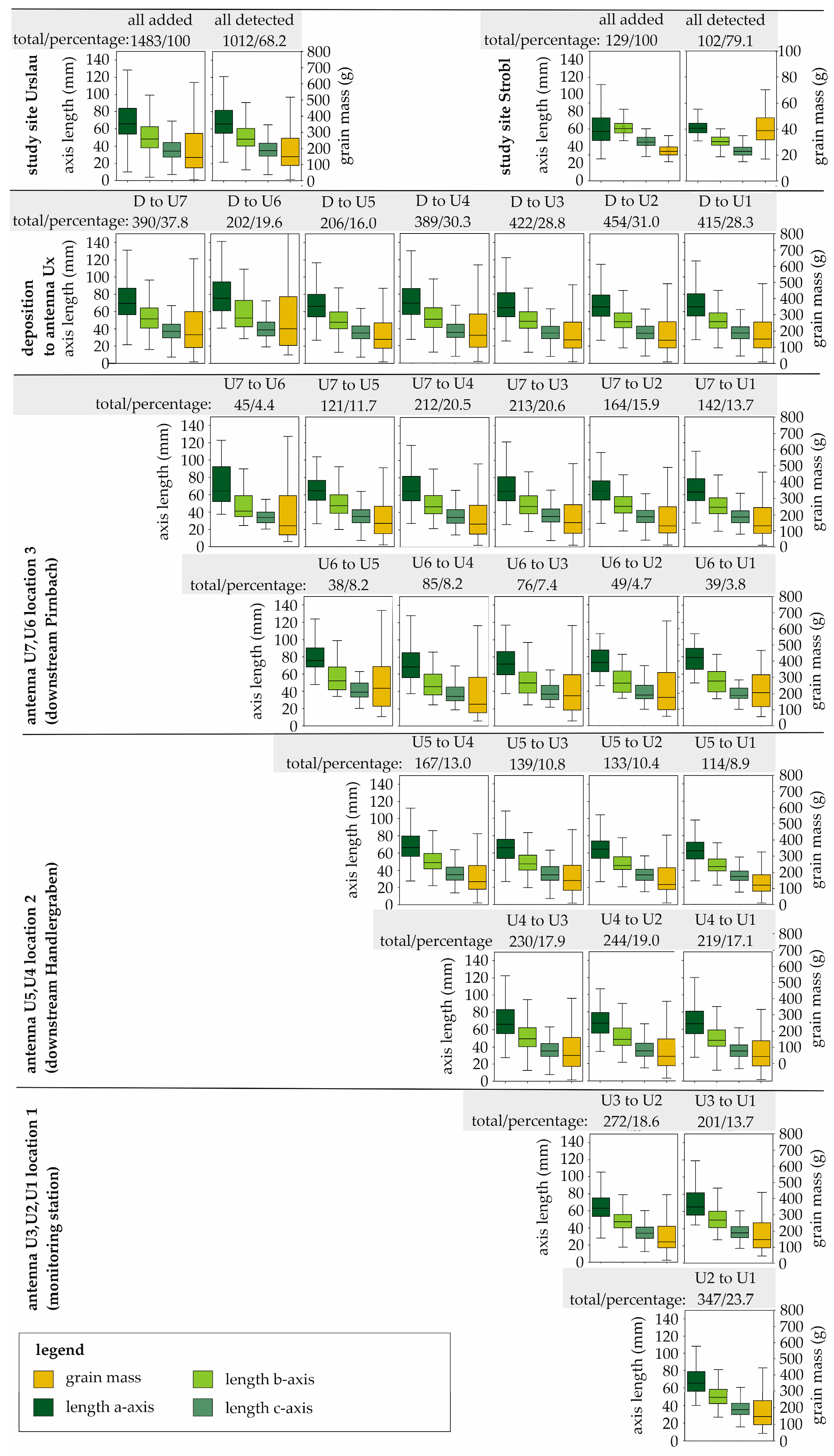

A total of 1483 stones were placed in the Urslau stream, and 129 were placed into the Strobler-Weißenbach in this study. Of these, 1012 were successfully detected after being transported in the Urslau and 102 were detected in the Strobler-Weißenbach. The statistical analysis focused on the following parameters: the transport distance, geometric dimensions of the stones (lengths of the a-, b-, and c-axes, and mass), measured particle velocity (vmeasured), and effective discharge (Qeff). The geometric dimensions of the stones exhibited significant variability. On average, the stones had the following measurements: 70.53 mm for the a-axis, 51.63 mm for the b-axis, and 37.17 mm for the c-axis. The largest stone measured 191 mm for the a-axis, 134 mm for the b-axis, and 99.12 mm for the c-axis, while the smallest stone measured just 10.12 mm for the a-axis, 12.81 mm for the b-axis, and 7.14 mm for the c-axis. This variability highlights the diversity of the stone dimensions used in the study. The stones’ mass also varied widely, with a median of 146.95 g and a mean of 235.65 g. The heaviest stone weighed 3017.4 g, while the lightest weighed only 8.74 g, demonstrating that even very small stones were successfully transported and detected.

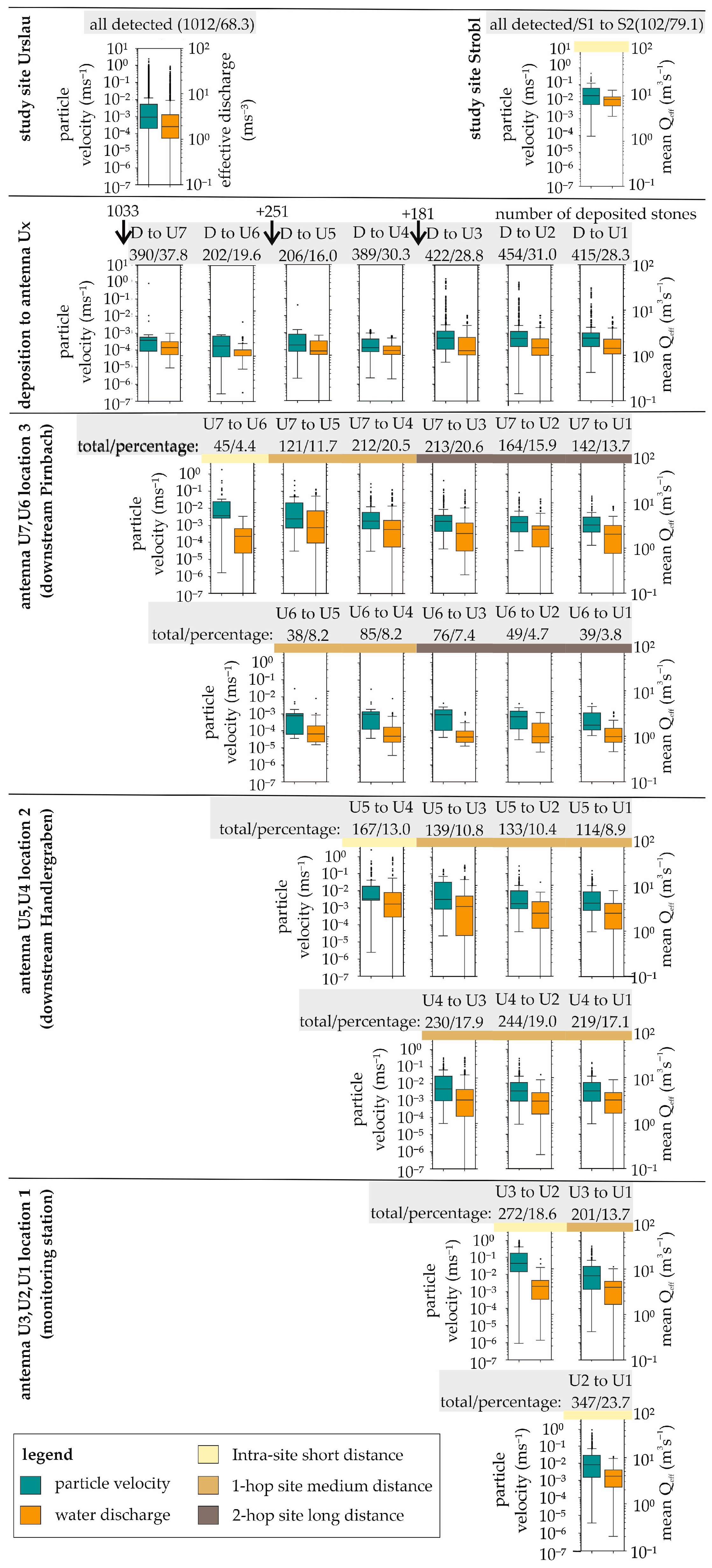

Figure 5 provides a comprehensive visualisation of the geometric parameters (a-, b-, c-axes) and the mass of all deposited and detected stones for this research, categorised by the study site and detection location along the stream. The figure is organised into multiple rows: The first row presents boxplots showing the geometric parameters and the mass of all deposited and detected stones for the Urslau and Strobl study sites. The Urslau grain sizes show significant variability, whereas smaller fractions were deliberately introduced in the Strobler-Weißenbach since the main focus here was on determining the velocity of smaller grain fractions. The second row presents the same parameters for deposited stones, grouped from the deposition point to the detecting antenna. In the figure, the antennas are ordered from left to right in the downstream direction, providing insights into the spatial distribution of detections. The total number of stones and percentage of the overall sample are displayed above the boxplots, demonstrating the detection efficiency of each antenna. For instance, 454 stones were detected at antenna U2, accounting for 31% of those introduced upstream of this antenna. The third, fourth, and fifth rows focus on the geometric parameters of stones detected at two antennas (double detections). The data are sorted from upstream to downstream and are grouped by the three antenna sites. Since double detections require stones to be recorded at two antennas, there are fewer double detections than total detections from release points to a single antenna. In summary, the results furnish a thorough synopsis of nine years of uninterrupted measurements, encompassing the physical characteristics of all 1612 stones, their transport behaviour, and their detection efficiency across an array of locations and conditions.

3.2. Particle Velocities

The ranges of the measured particle velocity and effective discharge are displayed in

Figure 6, which is similar to

Figure 5: The first row illustrates that the Urslau data contain a wide range of velocities and effective discharges. This variability can be attributed to the long measurement period (from 2016 to 2024), the diverse distances between the deposition points and the antennas, and the distances between the antennas themselves. By contrast, the Strobler-Weißenbach data show a narrower range of variability because they are based on just two targeted experiments, each lasting two weeks. The second row presents, comparable to

Figure 5, the values from deposition to antenna. The transport distances are arranged in ascending order from left to right, and arrows indicate the upstream deposition points and the number of stones introduced at each point. It is evident that particle velocities decrease as transport distances increase. For example, 1033 stones were introduced upstream of location 2, with an additional 251 released upstream of location 1 (near the monitoring station) and a further 181 released still further upstream. The mean velocity of the detected particles was found to be 0.022 m s

−1, with a median velocity of 0.001 m s

−1 and a maximum velocity of 2.47 m s

−1.

Rows three, four, and five display the transport velocities between the antennas, again grouped by the three sites and ordered from left to right in the downstream direction. The transport distances between the antennas, resulting from their downstream arrangement, are classified as intra-site (short distance), 1-hop site (medium distance), or 2-hop site (long distance, see legend). The distributions of the particle velocity and the corresponding effective discharge are shown for each transport reach in a boxplot diagram.

The data reveal that shorter transport distances are associated with higher particle velocities. Detection rates vary by location. The scatter of the effective discharge is caused by the timing of the detection of the tracer particle within the hydrograph. Furthermore, the best detection rates were achieved at location 1 (U1, U2, and U3), as this site was powered by grid electricity, ensuring high reliability. In contrast, U6 and U5 had the lowest detection rates, due to issues with the energy supply and defective antenna tuners.

3.3. Controls on Particle Velocity: Geometry, Mass, Discharge

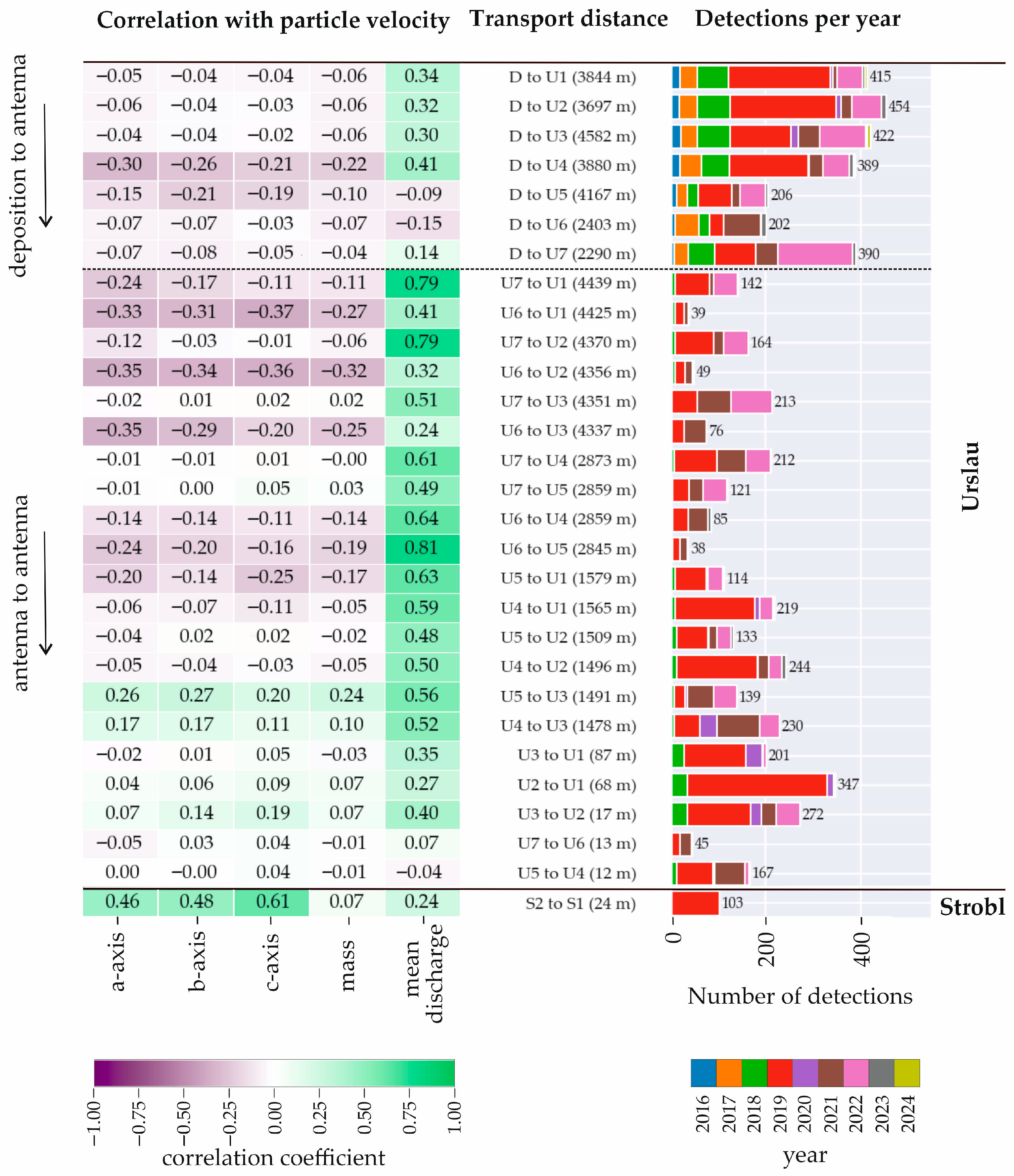

Figure 7 integrates the results from

Figure 5 and

Figure 6. It shows the correlations between particle transport velocities and grain parameters (a-, b-, c-axes and mass), as well as the mean discharge (mean Q

eff). The graph is divided between the two sites. Furthermore, the Urslau data are categorised into transport distances from the deposition point to the detecting antenna and inter-antenna distances. The data are arranged in descending order according to the transport distance.

Figure 7 is divided into three sections. The first section delineates the deposition process up to the detection stage. The subsequent section expounds on the double detections that occurred between two antennas at Urslau. The final section details the double detections that took place at Strobler-Weißenbach. The various lines are arranged in descending order according to the distance between two recordings. The left side of the graph displays the correlation coefficient between the velocity of particles and the length of their axes, as well as their mass and effective discharge. The right side of the graph contains a bar chart that displays the number of double detections for each transport section, separated by year (2016–2024). The most detections occurred in 2019 and 2022.

The three grain size axes (a, b, and c) predominantly exhibit weak or slightly negative correlations with the transport velocity across most antenna pairs. This suggests that the particle shape and size have little influence on the achieved velocities. The grain mass shows stronger positive correlations for two antenna pairs (U5–U3 and U4–U3), suggesting that heavier particles tend to move in certain channel sections. However, these effects remain moderate overall. For antenna-to-antenna distances that exceed 1400 m, a substantial correlation exists between the average discharge and the particle velocity. The data, when considered as a whole, indicates an average value of 0.56, with a correlation of 0.60 when U6 is excluded and a value of 0.48 when U6 is included. However, it should be noted that the U6 exhibited intermittent failure. The underlying causes of this phenomenon may include various factors, such as physical destruction, a disruption in the power supply, or issues related to tuning. The mean correlation value for short distances is approximately 0.28, which is significantly lower. The strongest relationships are found with the mean discharge (mean Qeff). This indicates that increased discharge substantially enhances transport velocities. Several antenna pairs, particularly at intermediate transport distances within the Urslau (e.g., U7–U1, U6–U1, and U7–U2), display high positive correlations (r ≈ 0.79). For very short transport paths (e.g., S2–S1), correlations with discharge are positive, albeit weaker. Conversely, the very long transport connections from the deposition site show no consistent relationship with discharge. This suggests that increased discharge makes longer yet well-defined transport steps within the Urslau system more likely. By contrast, very short distances (e.g., U5–U4: 12 m; U7–U6: 13 m; U3–U2: 17 m; S2–S1: 24 m) display only weak or inconsistent correlations with discharge. This suggests that the transport of particles between antennas in close proximity occurs largely independently of flow variability.

4. Discussion

This study presents a long-term dataset of monitored particle velocities, highlighting the capabilities of the RFID system and providing a foundation for the detailed analysis of the transport process. The study utilises stationary RFID antennas to demonstrate the capacity of RFID systems to provide precise, continuous, and high-resolution data on sediment transport. The findings highlight the importance of incorporating sophisticated monitoring technologies to address the spatial and temporal variability of sediment transport processes.

The use of RFID technology has become standard practice in sediment transport research, firmly establishing itself as the reference method over the past two decades. This assertion is evidenced by the deployment of over 30,000 RFID tracers in a variety of gravel-bed rivers around the globe [

15]. A comparative meta-analysis was conducted to ascertain the merits of the present method in comparison to traditional approaches, such as dye tracers or manual observations. The advantages of this approach are manifold, including superior temporal resolution and the capacity for uninterrupted, large-scale monitoring [

29,

59]. The available data indicate the existence of regional and hydrological differences. For instance, studies conducted on subglacial channels and regulated rivers have demonstrated varying detection rates. Contrary to the observations reported by Mao et al. [

20], who documented less variability of the transport velocities, our study noted higher levels of variability. This discrepancy can be attributed to the increased number of antennas and the longer monitoring period in our study, particularly in the Urslau case. The enhanced temporal and spatial coverage enabled a more nuanced comprehension of transport dynamics, encompassing the impact of particle properties and discharge levels on transport velocities. Stationary antennas and mobile search campaigns represent fundamentally different approaches of bedload tracing. The mobile antenna represents the Lagrangian approach, as particles are traced as they move within the river system. In Contrast the stationary antenna represents the Eulerian approach where articles are monitored passing a certain river cross-section. Mobile RFID tracer detections allow for the measurement of tracer movement within the river system. This enables the calculation of transport distances, dispersion, and average transport velocity for the entire sample before and after an event, or multiple events. In contrast, stationary antennas measure average transport speeds between the seeding site and the antenna. When two or more stationary antennas are used, transport velocity or average particle velocity during an event can be determined. By seeding tracers upstream of a stationary antenna, the initiation of motion can also be measured. These two approaches complement each other and provide a complete picture of the dynamics of bedload transport within the river system.

The Strobler-Weißenbach experiments provide specific insights into the dynamics of flood events. The Urslau experiment, which was conducted over eight years, additionally offers a unique opportunity to analyse long-term trends and seasonal variability in sediment transport. These complementary approaches underscore the necessity of both long-term and targeted short-term measurements to comprehensively understand the complex processes of sediment transport. The variability of transport velocities in the Urslau can be partly attributed to the heterogeneous geomorphological features and the wide distribution of grain sizes. The preceding observations underscore the necessity of incorporating geomorphological and hydraulic factors, such as the grain size, slope, discharge, and event history, into the analysis [

51]. This incorporation is essential to facilitate a more comprehensive understanding of sediment transport dynamics.

The detection efficiency of RFID tracers is subject to variation due to a variety of factors. These include the river morphology, burial depth of particles, sediment composition, and hydrological events such as flooding or snowmelt [

20,

24]. The characteristics of the channel, in conjunction with the presence of wood debris, have been demonstrated to exert a substantial influence on the transport distances and tracer recovery. Consequently, it is imperative to meticulously calibrate the system to ensure the generation of robust interpretations [

15]. Pivotal roles for seasonal changes, particularly those resulting in extreme flows of snowmelt or rainfall, have been identified in the mobilisation of sediments [

24,

51]. Consequently, it is imperative that these seasonal variations be incorporated into any analysis pertaining to tracer movement and detection rates. For instance, the detection rates in the Urslau exhibited significant variation. Antenna 6 achieved a mere 3.6% detection rate due to challenges with the energy supply and hardware malfunctions. Conversely, antenna 7 achieved the highest rate (37.8%) due to its proximity to the particle release point. These challenges underscore the importance of the meticulous calibration of antennas and the consideration of the channel morphology, which has the capacity to influence detection rates. The efficacy of passive RFID systems has been demonstrated in a variety of challenging environmental conditions, with studies indicating the attainment of high recovery rates under such circumstances. However, the effectiveness of these systems can be constrained by factors such as the reading range and particle burial. These limitations are of particular pertinence in alpine river systems, where the sediment coverage and dynamic river morphology can impede detection. Addressing these challenges will require further refinement of antenna configurations and the development of more robust systems. According to Cassel et al. [

56], the installation of a stationary antenna at the terminus of each mobile survey route is recommended in order to limit the survey area. However, the findings of this study indicate that redundancy with multiple antennas is preferable, as a single antenna will never detect 100% of the stones passing over it.

The long-term operation of stationary RFID systems in alpine rivers is characterised by numerous technical challenges that must be addressed to ensure stable and reliable performance. Our field study has demonstrated that the most critical factors in this regard are antenna dimensioning, power supply stability, time synchronisation, and hardware robustness.

The accurate measurement of the antenna is paramount for ensuring reliable signal transmission. The geometric configuration, wire diameter, and wire length must be selected so that the antenna operates within the appropriate inductance range. Minor alterations in parameters can induce impedance mismatches and result in signal instability. It is therefore imperative to calibrate the equipment with meticulous precision prior to installation to ensure a consistent detection performance.

A stable power supply was determined to be equally important. While solar-powered systems hold considerable appeal for deployment in remote locations, they have been observed to be susceptible to disruptions resulting from limited sunlight or inadequate battery capacity. Grid-based power systems have been demonstrated to offer enhanced reliability in operation and to mitigate data gaps. The expansion of solar capacity has the potential to mitigate these issues; however, it would result in a substantial increase in cost and logistical effort, particularly in alpine terrain.

Accurate time synchronisation across stations was identified as a critical prerequisite. At the inception of the study, conventional data loggers demonstrated time drift due to unstable quartz oscillators, resulting in temporal inconsistencies between antennas. The issue was resolved through the implementation of Raspberry Pi-based loggers, which facilitate time synchronisation, thereby ensuring sub-second accuracy. Such precision is imperative for high-frequency measurements and for deriving transport velocities from RFID data. However, the process of detecting the RFID tag with the RFID antenna is accompanied by a significant degree of uncertainty. The temporal discrepancy in detection outcomes is contingent upon the orientation of the target. The maximum measured transport velocity is indicated as follows: The tracer stone, when detected by two antennas, would be measured with an accuracy of 405 milliseconds at a velocity of 2.47 m per second. Given a distance of 12 m between the antennas, the detection measurement error would be approximately 8.3%. Assuming the tracer stone covers a distance of 12 m at a velocity of 2.47 m per second, the elapsed time is 4.86 s. Given a detection accuracy of 0.5 m per antenna, which corresponds to an aggregate detection accuracy of 1 m, the elapsed time would be 0.405 s. Given an average speed of 0.001 m per second, the measurement error would be 0.003375%, as it would require 12,000 s to travel 12 m at that velocity. The potential for signal interference from metallic materials in proximity to the antenna was determined to be negligible. A study was conducted to determine the impact of small steel components, such as mounting pins utilised for antenna installation in the riverbed, on the signal strength. The findings revealed that these components did not have a statistically significant effect on the detection range. At the Strobler-Weißenbach site, antennas anchored with steel pins demonstrated reliable performance, suggesting that a moderate metal presence does not compromise the electromagnetic field.

The occurrence of sporadic hardware instabilities, manifesting as system freezes and logger crashes, underscored the significance of the remote maintenance capabilities. The integration of Raspberry Pi control units enabled the execution of remote reboots and automated recovery routines, thereby enhancing the system uptime and reducing the necessity for field intervention.

Tuner reliability also influenced data consistency. While the underlying causes of tuner failure could not be discerned in all cases, the maintenance of spare units did prove advantageous. Fixed-frequency tuners demonstrated greater stability than auto-tuning systems, which occasionally exhibited overheating and the burning of the mosfet. For long-term installations, the use of fixed tuners is therefore recommended, as they have been shown to offer predictable performance and reduced maintenance requirements.

The erosion of the concrete casing lasted longer than expected. From 2018–2025, only one of seven antennas was destroyed due to erosion at the Urslau site. The stationary antennas at the Strobler-Weissenbach, on the other hand, were only pinned with metal stakes and lasted until a major flood event occurred in the summer of 2019.

In summary, the successful operation of stationary RFID systems in dynamic riverine environments depends not only on the technical characteristics of the sensors but also on a robust system design that anticipates environmental and operational constraints. Adequate consideration of factors such as the antenna configuration, power management, time synchronisation, and hardware maintenance has been demonstrated to result in substantial enhancements in the data quality and system reliability. These practical insights are crucial for improving the performance of future RFID-based monitoring networks in fluvial research. Technological advances have further enhanced the utility of RFID systems in sediment transport research. Active ultra-high-frequency (UHF) RFID tags, for instance, have been demonstrated to enhance the detection range and reliability in challenging settings [

15]. Recent advancements in methodologies, such as probabilistic localisation and the integration of RFID with digital elevation models (DEMs), have facilitated more precise spatial analyses [

19]. Machine learning has seen a surge in applications aimed at recognising patterns and enhancing predictive models of sediment transport [

15,

19]. The integration of RFID with acoustic and optical systems has yielded discernible advantages in multi-method validation and data quality [

19]. These technological advancements offer two major benefits. First, they enhance the precision of sediment transport monitoring. Second, they establish novel avenues for interdisciplinary research.

The integration of hydrology, geomorphology, and ecology through interdisciplinary research has led to significant advancements in our understanding of how sediment transport affects habitats and long-term landscape development [

15,

59]. RFID facilitates analyses of ecological impacts and helps in evaluating restoration interventions such as gravel augmentation [

15,

24]. This interdisciplinary approach is of particular value in alpine river systems, where sediment transport processes are closely linked to ecological dynamics and geomorphological stability. Moreover, the implementation of long-term RFID monitoring systems facilitates the documentation of trends attributable to climate change, including shifts in hydrological regimes and an increase in the frequency of extreme weather events. For instance, the analysis of long-term RFID monitoring data can provide a valuable basis for investigating the impacts of climate change on sediment transport. The documentation of alterations in hydrological regimes, including increased flood frequency or shortened snowmelt periods, is imperative. These data are essential for formulating adaptive management strategies that address the challenges posed by climate change. This approach aligns with the principles of adaptive management and impact assessment [

15].

The findings of this study have practical implications for the management of sediments and the protection of infrastructure against flooding. The implementation of RFID monitoring systems facilitates the effective and prolonged tracking of sediment particles across vast spatial domains at a relatively modest cost. This capacity provides key information for improving sediment transport models and guiding river restoration or flood management strategies. For instance, the prediction of bedload mobilisation as a function of discharge rates can facilitate the planning of retention systems and the design of flood protection measures. Furthermore, the results of this study can contribute to sediment management strategies aimed at optimising the reintroduction of sediment into river systems to promote geomorphological stability. By comprehending the interrelationships among particle properties, the transport velocity, and discharge, practitioners can formulate more efficacious interventions to mitigate sediment-related risks. The incorporation of stakeholder perspectives, including government authorities, further enhances the practical value and adoption of RFID monitoring [

59].

Key uncertainties persist, particularly regarding variable recovery rates, burial, antenna calibration, and limited data environments [

20,

28]. The scientific consensus emphasises the validation of RFID results using independent methods, such as physical sampling and remote sensing, to ensure robust conclusions [

28]. Furthermore, RFID-based bedload monitoring offers a cost-effective, scalable alternative to traditional techniques, supporting improved flood risk prediction and potentially reducing overall damage and costs [

28,

59]. There is also growing potential to integrate RFID datasets into regional and global sediment databases, fostering standardised approaches and comparative, multi-site research [

15].