Comparison of Process-Based and Machine Learning Models for Streamflow Simulation in Typical Basins in Northern and Southern China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Source

2.3. Model Description

2.3.1. SWAT Model Description

2.3.2. GWLF Model Description

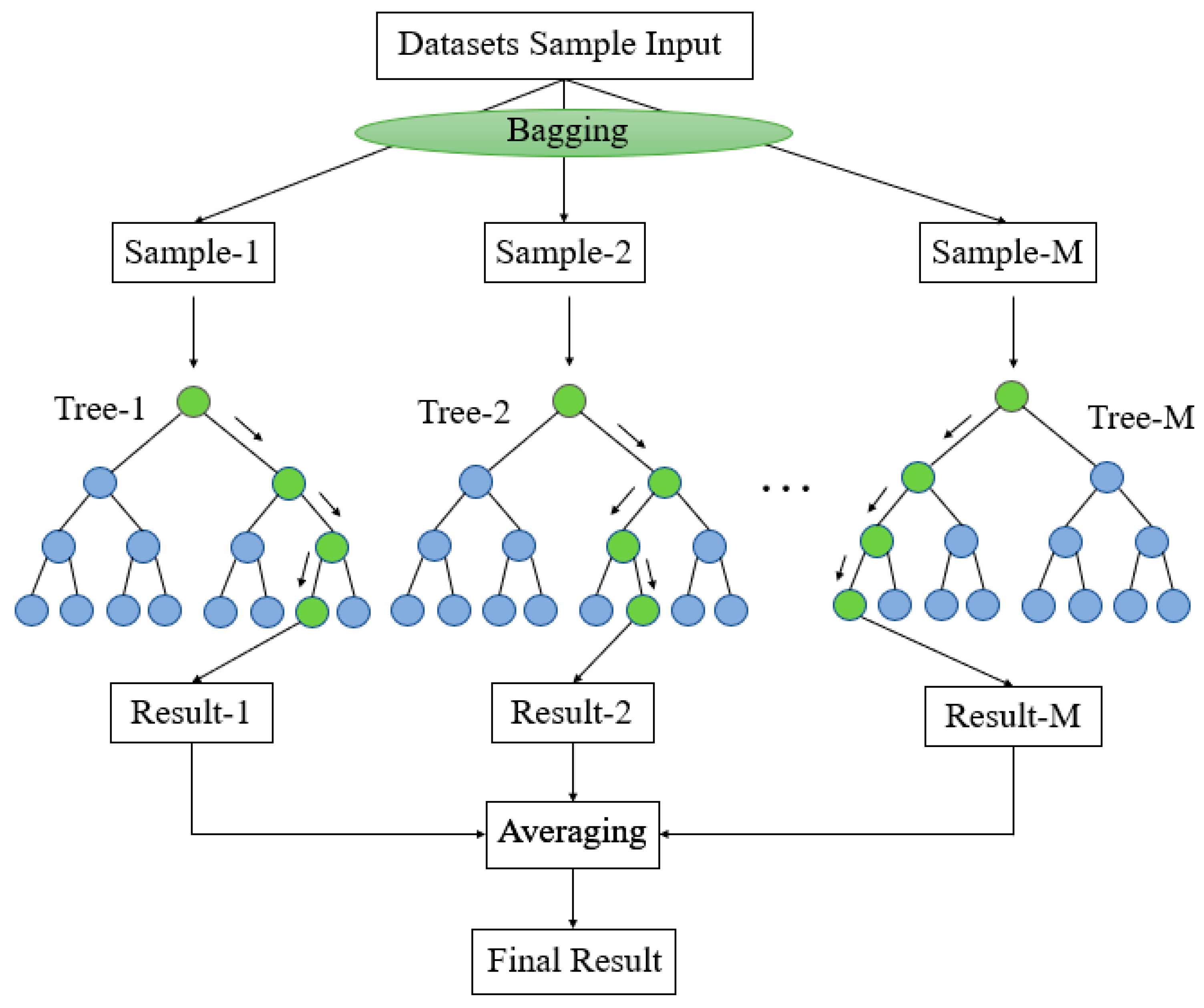

2.3.3. RF Model Description

2.4. Model Settings and Evaluation

2.4.1. SWAT Model

2.4.2. GWLF Model

2.4.3. RF Model

2.4.4. Performance Evaluation Indicators

3. Results and Discussion

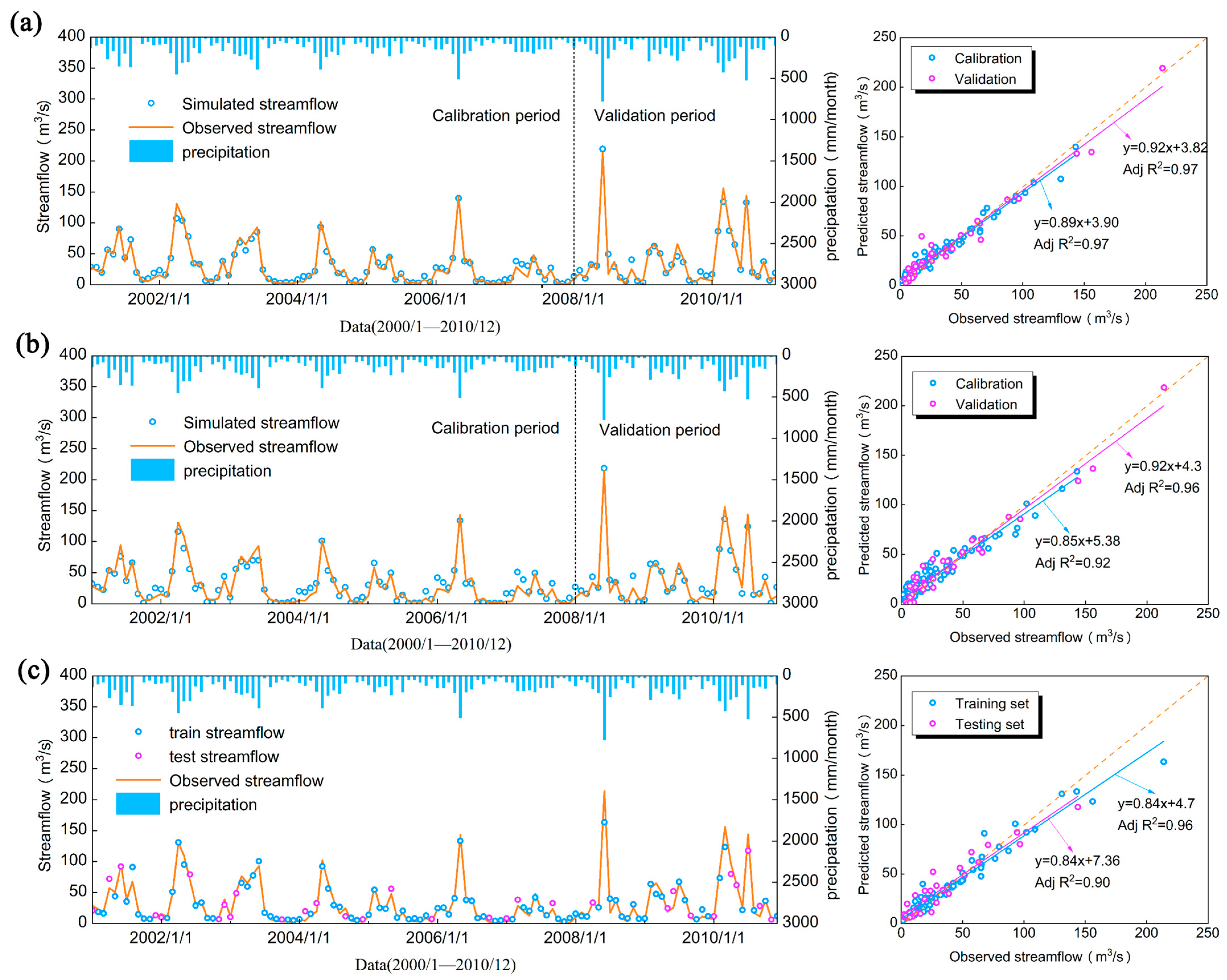

3.1. SWAT and GWLF Calibration

3.2. RF Training and Testing

3.3. Analysis and Comparison of the Model Performance in the SRB and SSB

3.4. Model Insights and Implications for Future Water Management

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Luo, X.; Yuan, X.; Zhu, S.; Xu, Z.; Meng, L.; Peng, J. A hybrid support vector regression framework for streamflow forecast. J. Hydrol. 2019, 568, 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, G.B.; da Silva, D.D.; Fernandes Filho, E.I.; Moreira, M.C.; Veloso, G.V.; de Souza Fraga, M.; Pinheiro, S.A.R. Effect of environmental covariable selection in the hydrological modeling using machine learning models to predict daily streamflow. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 290, 112625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarah, S.; Shah, W.; Ahmed, S. Modeling and comparing streamflow simulations in two different montane watersheds of western himalayas. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 15, 100689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, R.; Wang, T.; Yang, D.; Yang, Y. Streamflow decline threatens water security in the upper Yangtze river. J. Hydrol. 2022, 606, 127448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Zhang, X.; Hao, F.; Wu, Y.; Li, C.; Xu, Y. Evaluating the contributions of climate change and human activities to runoff in typical semi-arid area, China. J. Hydrol. 2020, 590, 125555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.K.; Liu, S.; Niu, W.J.; Li, B.J.; Wang, W.C.; Luo, B.; Miao, S.M. A modified sine cosine algorithm for accurate global optimization of numerical functions and multiple hydropower reservoirs operation. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2020, 208, 106461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, M.; Farokhnia, A.; Bahreinimotlagh, M.; Roozbahani, R. A hybrid of Random Forest and Deep Auto-Encoder with support vector regression methods for accuracy improvement and uncertainty reduction of long-term streamflow prediction. J. Hydrol. 2021, 597, 125717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ji, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Hou, X.; Ma, H. Consideration of streamflow forecast uncertainty in the development of short-term hydropower station optimal operation schemes: A novel approach based on mean-variance theory. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 304, 126929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo-Lacruz, J.; Morán-Tejeda, E.; Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Hannaford, J.; García, C.; Peña-Angulo, D.; Murphy, C. Streamflow frequency changes across western Europe and interactions with North Atlantic atmospheric circulation patterns. Glob. Planet. Change 2022, 212, 103797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teutschbein, C.; Grabs, T.; Karlsen, R.H.; Laudon, H.; Bishop, K. Hydrological response to changing climate conditions: Spatial streamflow variability in the boreal region. Water Resour. Res. 2015, 51, 9425–9446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadler, J.M.; Appling, A.P.; Read, J.S.; Oliver, S.K.; Jia, X.; Zwart, J.A.; Kumar, V. Multi-Task Deep Learning of Daily Streamflow and Water Temperature. Water Resour. Res. 2022, 58, e2021WR030138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Koropeckyj-Cox, L. SWAT model application for evaluating agricultural conservation practice effectiveness in reducing phosphorous loss from the Western Lake Erie Basin. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 302, 114000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.H.; Pachepsky, Y.A.; Oliver, D.M.; Muirhead, R.W.; Park, Y.; Quilliam, R.S.; Shelton, D.R. Modeling fate and transport of fecally-derived microorganisms at the watershed scale: State of the science and future opportunities. Water Res. 2016, 100, 38–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wei, G.; Zhong, Y.; Wang, G.; Shen, Z. Targeting priority management areas for multiple pollutants from non-point sources. J. Hazard. Mater. 2014, 280, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Zhong, Y.; Huang, Q.; Chen, L. Identifying non-point source priority management areas in watersheds with multiple functional zones. Water Res. 2015, 68, 563–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.L.; Gassman, P.W.; Yang, X.; Haywood, J. A review of SWAT applications, performance and future needs for simulation of hydro-climatic extremes. Adv. Water Resour. 2020, 143, 103662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, J.; Liu, M.; Wang, D.; Swaney, D.P.; Wang, Y. Application of the ReNuMa model in the Sha He river watershed: Tools for watershed environmental management. J. Environ. Manag. 2013, 124, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederiksen, R.R.; Molina-Navarro, E. The importance of subsurface drainage on model performance and water balance in an agricultural catchment using SWAT and SWAT-MODFLOW. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 255, 107058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niraula, R.; Kalin, L.; Srivastava, P.; Anderson, C.J. Identifying critical source areas of nonpoint source pollution with SWAT and GWLF. Ecol. Model. 2013, 268, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, F.M.; de Oliveira, R.P.; Mauad, F.F. Evaluating a parsimonious watershed model versus SWAT to estimate streamflow, soil loss and river contamination in two case studies in Tietê river basin, São Paulo, Brazil. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2020, 29, 100685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, H.; Wei, J.; Wu, W.; Jiang, Y.; Chu, Q.; Meng, X. A classification-based deep belief networks model framework for daily streamflow forecasting. J. Hydrol. 2021, 595, 125967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Ramsankaran, R.; Brocca, L.; Muñoz-Arriola, F. A simple machine learning approach to model real-time streamflow using satellite inputs: Demonstration in a data scarce catchment. J. Hydrol. 2021, 595, 126046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, W.J.; Feng, Z.K. Evaluating the performances of several artificial intelligence methods in forecasting daily streamflow time series for sustainable water resources management. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 64, 102562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimeno-Sáez, P.; Martínez-España, R.; Casalí, J.; Pérez-Sánchez, J.; Senent-Aparicio, J. A comparison of performance of SWAT and machine learning models for predicting sediment load in a forested Basin, Northern Spain. CATENA 2022, 212, 105953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, R.G.; da Silva, D.D.; Elesbon, A.A.A.; Fernandes-Filho, E.I.; Veloso, G.V.; de Souza Fraga, M.; Ferreira, L.B. Machine learning models for streamflow regionalization in a tropical watershed. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 280, 111713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaseen, Z.M.; El-shafie, A.; Jaafar, O.; Afan, H.A.; Sayl, K.N. Artificial intelligence based models for stream-flow forecasting: 2000–2015. J. Hydrol. 2015, 530, 829–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Li, S.; Hu, J.; Huang, J. A modeling approach to evaluating the impacts of policy-induced land management practices on non-point source pollution: A case study of the Liuxi River watershed, China. Agric. Water Manag. 2014, 131, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, F.; Wei, Y.D.; Gao, J.; Chen, W. Water crisis, environmental regulations and location dynamics of pollution-intensive industries in China: A study of the Taihu Lake watershed. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 216, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wang, C.; Ren, Q.; Liu, X.; Ren, J.; Kang, G.; Wang, Y. Long-term water quality dynamics and trend assessment reveal the effectiveness of ecological compensation: Insights from China’s first cross-provincial compensation watershed. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 169, 112853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Di, Z.; Duan, Q. Effect of sensitivity analysis on parameter optimization: Case study based on streamflow simulations using the SWAT model in China. J. Hydrol. 2021, 603, 126896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeyrani, F.; Morid, S.; Srinivasan, R. Assessing basin blue–green available water components under different management and climate scenarios using SWAT. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 256, 107074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, B.M.; Lehning, D.W.; Corradini, K.J.; Petersen, G.W.; Robillard, P.D. A Comprehensive GIS-Based Modeling Approach for Predicting Nutrient Loads in Watersheds. J. Spat. Hydrol. 2002, 2, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Sharifi, A.; Yen, H.; Boomer, K.M.B.; Kalin, L.; Li, X.; Weller, D.E. Using multiple watershed models to assess the water quality impacts of alternate land development scenarios for a small community. CATENA 2017, 150, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.-S.; Lin, I.W. Modification of generalized watershed loading functions (GWLF) for daily flow simulation. Paddy Water Environ. 2014, 13, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Abbasi, M.; Yang, X.; Ren, L.; Hosseini-Moghari, S.-M.; Döll, P. Estimation of the prevalence of non-perennial rivers and streams in anthropogenically altered river basins by random Forest modeling: A case study for the Yellow River basin. J. Hydrol. 2025, 656, 132910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saedi, J.; Sharifi, M.R.; Saremi, A.; Babazadeh, H. Assessing the impact of climate change and human activity on streamflow in a semiarid basin using precipitation and baseflow analysis. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 9228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbaspour, K.C.; Rouholahnejad, E.; Vaghefi, S.; Srinivasan, R.; Yang, H.; Kløve, B. A continental-scale hydrology and water quality model for Europe: Calibration and uncertainty of a high-resolution large-scale SWAT model. J. Hydrol. 2015, 524, 733–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Z.; Kang, G.; Chu, C.; Qiu, Y.; Xu, Z.; Wang, Y. Comparison of SWAT and GWLF Model Simulation Performance in Humid South and Semi-Arid North of China. Water 2017, 9, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, J.; Swaney, D.P.; Hong, B.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.-L. Estimation of watershed hydrologic processes in arid conditions with a modified watershed model. J. Hydrol. 2014, 519, 3550–3556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Gallichand, J. Use of the SHAW model to assess soil water recovery after apple trees in the gully region of the Loess Plateau, China. Agric. Water Manag. 2006, 85, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren-Jun, Z. The Xinanjiang model applied in China. J. Hydrol. 1992, 135, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodson, T.O.; Over, T.M.; Foks, S.S. Mean Squared Error, Deconstructed. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 2021, 13, e2021MS002681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milly, P.C.D.; Betancourt, J.; Falkenmark, M.; Hirsch, R.M.; Kundzewicz, Z.W.; Lettenmaier, D.P.; Stouffer, R.J. Stationarity is Dead: Whither Water Management? Science 2008, 319, 573–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, H.; Wang, L.X.; Zhang, J.W.; Liu, Z.; Yang, C. Hydrological simulation and prediction of the Jinghe River Basin based on CMIP6 climate scenario. Water Resour. Hydropower Eng. 2025, 56, 89–103. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.Y.; Jia, W.H.; Wang, S.; Feng, Z.; Qin, Y.; Zhang, K.; Liu, X.; Li, J. Research on the variation trends of precipitation and runoff in the Pearl River Basin based on innovative trend analysis method. Water Resour. Hydropower Eng. 2025, 56, 52–69. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Xia, C.L.; Song, Z.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, G.; Dai, C. Characteristics of extreme hydrological evolution in Nenjiang River Basin under future climate change scenarios. Water Resour. Hydropower Eng. 2025, 56, 109–123. [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, R.; Liu, Z.W.; Dai, H.C.; Liang, L.L.; Jiang, D.G.; Xu, Z.; Yin, Z.K.; Yang, H.; Lv, Z.Y. Characteristic and prediction of runoff change in the Yangtze River Basin. Water Resour. Hydropower Eng. 2023, 54, 87–97. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, X.; Sun, Y.; Li, Y.; Tang, S.W.; Shu, X.S. Analysis of annual runoff forecasting methods and the influence of factors in watersheds. Water Resour. Hydropower Eng. 2023, 54, 113–123. [Google Scholar]

- Devia, G.K.; Ganasri, B.P.; Dwarakish, G.S. A Review on Hydrological Models. Aquat. Procedia 2015, 4, 1001–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohl, J.P.; Wood, R.R.; Frank, C.; Astagneau, P.C.; Peters, J.; Brunner, M.I. Hybrid models generalize better to warmer climate conditions than process-based and purely data-driven models. EGUsphere 2025, preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapas, M.R.; Howard, G.; Etheridge, R.; Mair, M.; Peralta, A.L. Integrating human decision-making into a hydrological model to accurately estimate the impacts of agricultural policies. Commun. Earth Environ. 2025, 6, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, L.T.; Luo, L.; Finley, A. Evaluation of random forests for short-term daily streamflow forecasting in rainfall- and snowmelt-driven watersheds. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2021, 25, 2997–3015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altarawneh, E.S.; Sharil, S.; Razali, S.F.M.; Ahmed, A.N.; El-Shafie, A. Hybrid hydrological modeling: Integration of machine learning and conventional hydrology. Phys. Chem. Earth Parts A/B/C 2025, 141, 104150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Data Type | Data Source | Resolution | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Meteorological data | National Weather Science Data Center (http://data.cma.cn/ (accessed on 15 May 2023)) | daily | Precipitation, temperatures, relative humidity, wind speed, solar radiation |

| Rainfall station data | Local hydrological bureau | daily | Precipitation |

| Evapotranspiration data | Institute of Tibetan Plateau Research, Chinese Academy of Sciences (http://data.tpdc.ac.cn/zh-hans/ (accessed on 15 May 2023)) | monthly | Evapotranspiration |

| Hydrological data | Local hydrological bureau | daily | Streamflow |

| DEM | Geospatial Data Cloud (https://www.gscloud.cn/ (accessed on 15 May 2023)) | 30 m | Digital elevation model |

| Land use | Resource and Environmental Science and Data Center (https://www.resdc.cn/ (accessed on 15 May 2023)) | 1:1,000,000 | Land use type |

| Soil | Resource and Environmental Science and Data Center (https://www.resdc.cn/ (accessed on 15 May 2023)) | 1:1,000,000 | Soil type |

| Scenarios | Independent Variable | Dependent Variable |

|---|---|---|

| I | Pt, ET, AT, RH, WS, SR | Qt |

| II | Pt-1, ET, AT, RH, WS, SR | Qt |

| III | Pt-2, ET, AT, RH, WS, SR | Qt |

| IV | Pt-3, ET, AT, RH, WS, SR | Qt |

| Statistical Metrics | Formula | Range |

|---|---|---|

| R2 | [0, 1] | |

| NSE | [–∞, 1] | |

| MAE | [0, ∞] | |

| RMSE | [0, ∞] |

| Model | Parameter | Description | Default Value Range | Calibrated Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SRB | SSB | ||||

| SWAT | v__CN2.mgt | SCS runoff curve number | 35~98 | 46.47 | 80.06 |

| v__ESCO.hru | Soil evaporation compensation factor | 0~1 | 0.62 | 0.91 | |

| v__SOL_AWC.sol | Available water capacity of the soil layer | 0~1 | 0.88 | 0.36 | |

| v__GW_REVAP.gw | Groundwater “revap” coefficient | 0.02~0.2 | 0.04 | 0.07 | |

| v__GWQMN.gw | Threshold depth of water in the shallow aquifer required for return flow to occur | 0~5000 | 102.5 | 848.87 | |

| v__REVAPMN.gw | Threshold depth of water in the shallow aquifer for “revap” to occur | 0~500 | 210.48 | 373.4 | |

| v__ALPHA_BF.gw | Baseflow alpha factor | 0~1 | 0.59 | 0.88 | |

| v__SOL_K.sol | Saturated hydraulic conductivity | 0~2000 | 23.5 | 10 | |

| v__SFTMP.bsn | Snowfall temperature | −20~20 | 10.59 | 13.4 | |

| v__RCHRG_DP.gw | Deep aquifer percolation fraction | 0~1 | 0.47 | 0.23 | |

| v__LAT_TTIME.hru | Lateral flow travel time | 0~30 | 1.86 | 0.67 | |

| v__SOL_ALB.sol | Moist soil albedo | 0~0.25 | 0.18 | 0.11 | |

| v__SURLAG.bsn | Surface runoff lag coefficient | 0.05~24 | 14.87 | 5.27 | |

| v__SMTMP.bsn | Snowmelt base temperature | −20~20 | 7.03 | 4.28 | |

| v__SOL_BD.sol | Moist bulk density | 0.9~2.5 | 1.57 | 1.74 | |

| GWLF | CN2 | SCS runoff curve number | 0~100 | Varies | Varies |

| (40–100) a | (45–100) a | ||||

| Recess coefficient | Groundwater discharge coefficient | 0.1 | 0.004 | 0.158 | |

| Seepage coefficient | Groundwater seepage constant | 0 | 0.008 | 0.02 | |

| Unsat Avail Wat | Available soil water capacity | - | 14.05 | 9.65 | |

| Watershed | Model | Scenario | Model Performance Metrics Calibration (Validation) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | NSE | MAE | RMSE | |||

| SRB | SWAT | - | 0.87 | 0.86 | 1.02 | 1.35 |

| (0.86) | (0.60) | (1.09) | (1.29) | |||

| GWLF | - | 0.83 | 0.82 | 1.07 | 1.53 | |

| (0.60) | (0.58) | (1.24) | (1.58) | |||

| RF | I | 0.90 | 0.80 | 1.50 | 0.88 | |

| (0.44) | (0.67) | (2.00) | (1.53) | |||

| II | 0.90 | 0.81 | 0.85 | 1.43 | ||

| (0.44) | (0.48) | (1.55) | (2.03) | |||

| III | 0.89 | 0.79 | 0.94 | 1.59 | ||

| (0.63) | (0.66) | (1.06) | (1.36) | |||

| IV | 0.91 | 0.79 | 0.92 | 1.62 | ||

| (0.53) | (0.56) | (1.31) | (1.75) | |||

| SSB | SWAT | - | 0.97 | 0.97 | 4.08 | 5.72 |

| (0.96) | (0.96) | (6.08) | (9.05) | |||

| GWLF | - | 0.93 | 0.92 | 6.84 | 8.87 | |

| (0.96) | (0.96) | (7.40) | (9.66) | |||

| RF | I | 0.96 | 0.94 | 5.21 | 8.58 | |

| (0.91) | (0.90) | (7.82) | (10.37) | |||

| II | 0.96 | 0.96 | 4.67 | 8.26 | ||

| (0.85) | (0.89) | (8.69) | (12.68) | |||

| III | 0.97 | 0.96 | 4.44 | 7.65 | ||

| (0.89) | (0.88) | (8.71) | (11.84) | |||

| IV | 0.97 | 0.96 | 4.52 | 7.59 | ||

| (0.90) | (0.89) | (8.53) | (11.33) | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ye, R.; Zhang, F.; Ren, J.; Wu, T.; Chen, H. Comparison of Process-Based and Machine Learning Models for Streamflow Simulation in Typical Basins in Northern and Southern China. Water 2025, 17, 3498. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243498

Ye R, Zhang F, Ren J, Wu T, Chen H. Comparison of Process-Based and Machine Learning Models for Streamflow Simulation in Typical Basins in Northern and Southern China. Water. 2025; 17(24):3498. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243498

Chicago/Turabian StyleYe, Rui, Feng Zhang, Jiaxue Ren, Tao Wu, and Haitao Chen. 2025. "Comparison of Process-Based and Machine Learning Models for Streamflow Simulation in Typical Basins in Northern and Southern China" Water 17, no. 24: 3498. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243498

APA StyleYe, R., Zhang, F., Ren, J., Wu, T., & Chen, H. (2025). Comparison of Process-Based and Machine Learning Models for Streamflow Simulation in Typical Basins in Northern and Southern China. Water, 17(24), 3498. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243498