Failure Mechanism of Steep Rock Slope Under the Mining Activities and Rainfall: A Case Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Engineering Background

2.1. Engineering Geology

2.2. Human Engineering Activities

3. Methods

3.1. Numerical Model

3.2. Monitoring Point Layout and Simulation Scenarios

4. Results

4.1. Analysis of Slope Displacement

- NRUE—Nonrainfall Unexcavated; NRSE—Nonrainfall Semi-excavated;

- NRFE—Nonrainfall Fully Excavated; RUE—Rainfall Unexcavated;

- RSE—Rainfall Semi-excavated; RFE—Rainfall Fully Excavated;

4.2. Analysis of Maximum Principal Stress

4.3. Analysis of Minimum Principal Stress

5. Discussion

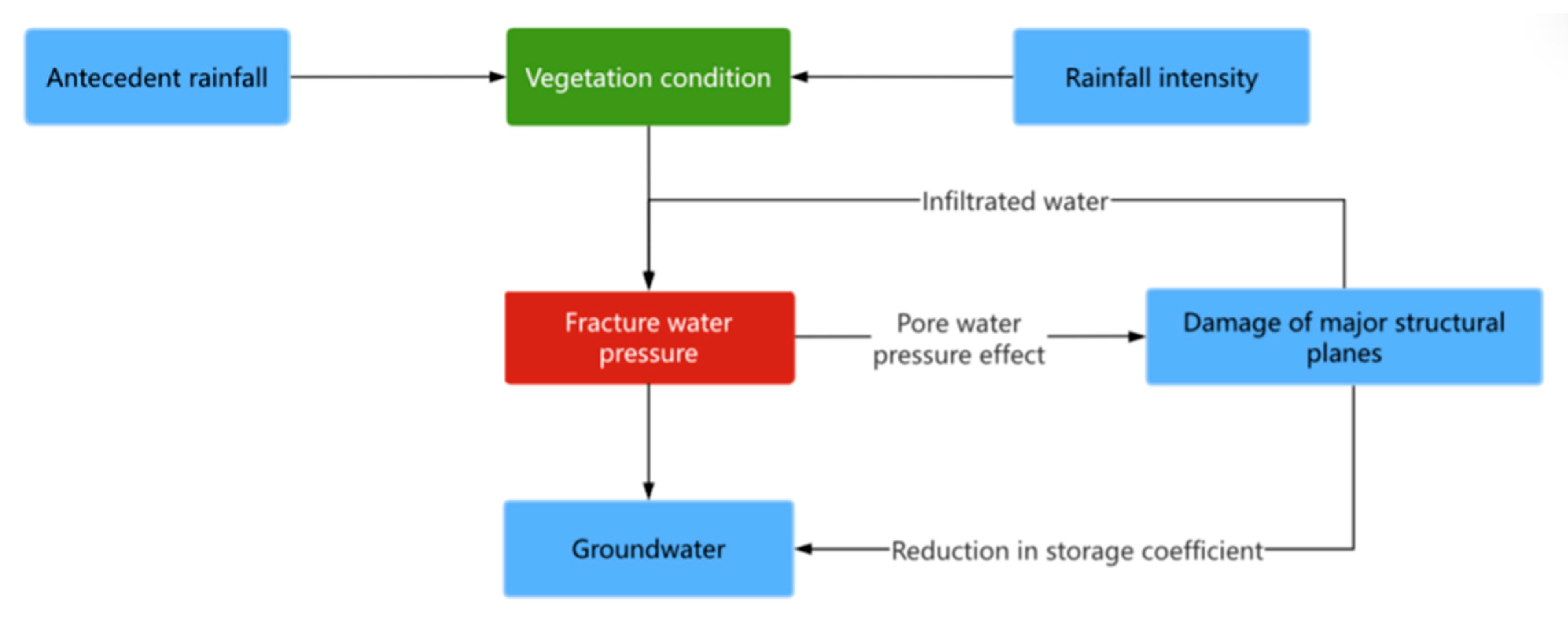

5.1. Mechanism Analysis of Instability of High Steep Slope Under Rainfall

- (1)

- Relationship between Rainfall and Rock Mass in Danger

- (2)

- Relationship between Groundwater and Rock Mass in Danger

- (3)

- Fracture Water Pressure

5.2. Mechanism Analysis of Instability of High Steep Slope Under Mining Activities

5.3. Limitations and Prospects

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- Through the analysis of the combined effects of mining and rainfall on steep rock slopes, in the initial stage, mining activities cause localized stress redistribution in the rock mass, leading to the formation of fractures and resulting in localized softening and deformation of the rock. Under the influence of rainfall, the water pressure within the cracks increases continuously, wetting the rock mass and reducing its shear strength. Ultimately, under the combined effects of these two factors, the landslide mass enters the failure stage.

- (2)

- In the deformation and instability process of steep rock slopes, both mining activities and rainfall play important roles, but their impact mechanisms are significantly different. According to the results of numerical simulations, the increase in crack width and displacement during rainfall is much greater than that during excavation. Therefore, in the process of landslide formation and development, mining mainly contributes to the initial stage of the landslide, while rainfall dominates the triggering stage and the rapid development phase.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhou, J.; Tang, M.; Xu, Q.; Wu, H.; Wang, X. An early warning model for rainfall-induced landslides in Chongqing based on rainfall threshold. Mt. Res. 2022, 40, 847–858. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, G.; Huang, G.; Du, Y.; Tu, R.; Han, J.; Wan, L. A low-cost real-time monitoring system for landslide deformation based on BeiDou cloud. J. Eng. Geol. 2018, 26, 1008–1016. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Meng, H.; Dong, Y.; Hu, S.E. Main types and characterisitics of geo-hazard in China—Based on the results of geo-hazard survey in 290 counties. J. Geol. Disasters Prev. China 2004, 15, 32–37. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Q.; Huang, R.; Yin, Y.; Hou, S.; Dong, X.; Fan, X.; Tang, M. The Jiweishan landslide of June 5, 2009 in Wulong, Chongqing: Characteristics and failure mechanism. J. Eng. Geol. 2009, 17, 433–444. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, D.; Sun, W.; Zhang, Z.; Hu, M.; Yu, S.; Chen, P.; Hu, L.; Zhu, T. Patterns of landslide development and their correlation with rainfall in Chongqing during 2024 flood season. Bull. Soil Water Conserv. 2025, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Yin, Y.; Feng, Z.; Li, B. Analysis of characteristics and stability for Zengziyan—Eryayan unstable rocks belt in Nanchuan county Chongqing. Chin. J. Geol. Hazard Control 2015, 26, 16–22. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, R. Large-scale landslides and their sliding mechanisms in China since the 20th century. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2007, 26, 433–454. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Cai, Y.; Zhang, K.; Yang, X.; Wang, L. Influence of deformation parameters of backfill body on slope stability after transition from open-pit to underground. Min. Metall. Eng. 2019, 39, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Dai, Z.; Guo, L.; Fang, W. Stability Analysis of Recent Failed Red Clay Landslides Influenced by Cracks and Rainfall Based on the XGBoost-PSO-SVR Model. Water 2025, 17, 1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wang, Y.; Hou, D.; Jiang, S.; Gong, B.; Li, X. Simulating the Failure Mechanism of High-Slope Angles Under Rainfall-Mining Coupling Using MatDEM. Water 2025, 17, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Zhang, R.; Yang, C.; Qing, M. Analysis of seepage in expansive soil slopes based on fluid-solid coupling. Highw. Automot. Appl. 2023, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, H. Study on the Instability Mechanism of Under-construction Highway Slopes under Rainfall Conditions. Railw. Constr. Technol. 2025, 106–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Wang, G.; Feng, Z.; Wang, W.P. Failure mechanism of steeply inclined rock slopes induced by underground mining. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2015, 34, 1148–1161. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Li, X.; Li, C.; Liu, Z. Mechanism of Surface Subsidence Induced by Underground Mining. Min. Metall. Eng. 2020, 40, 16–21. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Y.; Wang, F.; Ren, Q. Numerical simulation of surface subsidence caused by underground mining using discrete element software PFC2D. Min. Metall. Eng. 2023, 43, 30–34. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang, Y.; Hu, X.; He, W.; Shen, D.; Zhu, Y. Stability Analysis of a Rocky Slope with a Weak Interbedded Layer under Rainfall Infiltration Conditions. Water 2024, 16, 604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Cai, P.; Zhan, J.; Yang, Y.; Yao, Z.; Yu, Z. Deformation Patterns and Failure Mechanisms of Soft-Hard-Interbedded Anti-Inclined Layered Rock Slope in Wolong Open-Pit Coal Mine. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Zhang, J.; Song, Y.; Feng, Z.; Tian, J.; Gu, J.; Li, X. Failure Mechanism of Sandy Soil Slopes Under High-Angle Normal Bedrock-Fault Dislocation: Physical Model Tests. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, Q.; Hu, Y.; Teng, L.; Yang, S. Evolution Characteristics of Mining Fissures in Overlying Strata of Stope After Converting from Open-Pit to Underground. Arab. J. Geosci. 2021, 14, 2795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yao, A.; Gong, Y. Deformation and Failure Mechanism of a Massive Ancient Anti-Dip River-Damming Landslide in the Upper Jinsha River. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Wang, J.; Li, Z.; Kong, Y.; Zhang, L.; Qi, G. Study on Deformation Characteristics of Toppling Failure of Anti-Dip Rock Slopes Under Different Soft and Hard Rock Conditions. Front. Earth Sci. 2024, 12, 1339169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Z.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, C.; Hao, Z.; Zhang, X.; Hu, X. Design and operation of App-based intelligent landslide monitoring system: The case of Three Gorges Reservoir Region. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2019, 10, 1209–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z. Analysis of Rock Slope Stability: Principles, Methods, and Procedures; China Water Power and Hydropower Press: Beijing, China, 2005; pp. 65–75. [Google Scholar]

- Itasca Consulting Group. UDEC User’s Guide, 6th ed.; Itasca Consulting Group: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2014; pp. 25–30. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, M. Rock Mechanics and Engineering; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2002; pp. 105–114. [Google Scholar]

- Cundall, P.A.; Strack, O.D.L. A discrete numerical model for granular assemblies. Geotechnique 1979, 29, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Guo, M.; Wang, S.; Ge, X.R. Vector sum method for slope stability analysis based on discrete elements. Rock Soil Mech. 2016, 37, 592–600. [Google Scholar]

- He, S.; Li, Y.; Aydin, A. A comparative study of UDEC simulations of an unsupported rock tunnel. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2018, 72, 242–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, G. Numerical Manifold Method and Discontinuous Deformation Analysis; Pei, J., Translator; Tsinghua University Press: Beijing, China, 1997; pp. 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, J.; Wang, J. Analysis of the mechanical model of overburden rock strata and the conditions for fracture failure due to mining. J. China Coal Soc. 2002, 27, 16–20. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Li, S.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Y.; Guo, X. Development of new similarity materials for geomechanical model tests. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2006, 25, 1842–1847. [Google Scholar]

- Ning, Y.; Xu, W.; Zheng, W. Application in complicated high slope with strength reduction method based on discrete element method. Rock Soil Mech. 2007, 28, 569–574. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, E.M.; Roth, W.H. Drescher A Slope stability analysis by strength reduction. Geotechnique 1999, 49, 835–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z. Research on Early Warning Criteria for Soil Landslide Induced by Typhoon Rain Based on Monitoring Data. Master’s Thesis, Fuzhou University, Fuzhou, China, 2015; pp. 48–53. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, Y.; Wang, S. Stability analysis of jointed rock slope by strength reduction method based on UDEC. Rock Soil Mech. 2006, 27, 1693–1698. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, S.; Zheng, Y.; Shi, W.; Wang, J.L. Analysis on safety factor of slope by strength reduction FEM. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2002, 24, 343–346. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Shang, J.; Li, W.; Wang, X.; Gao, L. Investigation of stress and deformation characteristics of a geotextile tubes dam understrength reduction via discrete element method. J. N. China Univ. Water Resour. Electr. Power (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2021, 42, 83–91. [Google Scholar]

- Chaves, H.M.L.; Montalvão, M.T.L.; Fonseca, M.R.S. Mapping Wet Areas and Drainage Networks of Data-Scarce Catchments Using Topographic Attributes. Water 2025, 17, 2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Zeng, L.; Wang, G.; Jiang, Z.M.; Yang, Q.X. Stability analysis of soft rock slopes under rainfall infiltration conditions. Rock Soil Mech. 2012, 33, 2359–2365. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Wang, H.; Fu, H.; Liu, B.C. Influences of rainfall infiltration on stability of accumulation slope by in-situ monitoring test. J. Cent. S. Univ. Technol. 2009, 16, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Yin, K. Analysis of the infiltration mechanism of precipitation in rainfall-induced landslides. Rock Soil Mech. 2008, 29, 1061–1066. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Y. Mechanism of apparent dip slide of inclined bedding rockslide a case study of Jiweishan rockslide in Wulong, Chongqing. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2010, 29, 217–226. [Google Scholar]

- Hoek, E. Progressive caving induced by mining an inclined orebody. Trans. Inst. Min. Metall. 1974, 83, 133–139. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Z.; Li, B.; He, K. Rock collapse mechanism on highsteep slope failure in sub-horizontal thick-bedded mountains. J. Geomech. 2014, 20, 123–131. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J. Studies on several theoretical and technical problems related to subsidence during coal mining. Mine Surv. 2003, 3, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, X.; Chen, R.; Pu, H.; Guo, W. Analysis of the failure and collapse characteristics of key strata in thick overburden during mining. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2005, 24, 1289–1295. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, M.; Wang, C. Prediction of subsidence in thick loess-covered mountainous areas during mining. Coal Geol. Explor. 2001, 29, 44–47. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Dong, J.; Xu, G.; Cai, Z. Engineering impact of underground faults on overlying soil layers of different soil types. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2005, 24, 1868–1874. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Wei, L.; Xu, Q.; Li, H.; Wang, J. Structural Detection and Stability Monitoring of Deep Strata on a Slope Using High-Density Resistivity Method and FBG Strain Sensors. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolakopoulos, K.G.; Kyriou, A.; Koukouvelas, I.K.; Tomaras, N.; Lyros, E. UAV, GNSS, and InSAR Data Analyses for Landslide Monitoring in a Mountainous Village in Western Greece. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Rock Types | Rain | Density/(kg·m−3) | Elastic Modulus/GPa | Shear Modulus/GPa | Internal Friction Angle/(°) | Cohesion/MPa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Limestone | Yes Not | 2650 2650 | 12.5 12.7 | 5.5 5.5 | 39.0 39.0 | 1.8 1.8 |

| Shale | Yes Not | 2550 2550 | 9.4 9.7 | 4.2 4.2 | 36.3 36.5 | 1.4 1.4 |

| Sandstone-shale | Yes Not | 2600 2600 | 9.7 9.9 | 5.1 5.1 | 37.1 37.3 | 1.7 1.7 |

| Rock Types | Rain | Normal Stiffness/106 N/M | Tangential Stiffness/106 N/M | Internal Friction Angle/(°) | Cohesion/MPa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Limestone | Yes Not | 49 49 | 5.7 5.7 | 29.7 32.0 | 0.45 0.59 |

| Shale | Yes Not | 40 40 | 3.7 4.0 | 23.8 26.5 | 0.22 0.34 |

| Sandstone-shale | Yes Not | 42 42 | 4.1 4.3 | 25.4 38.7 | 0.27 0.38 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ning, K.; Li, Z.-Q. Failure Mechanism of Steep Rock Slope Under the Mining Activities and Rainfall: A Case Study. Water 2026, 18, 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010056

Ning K, Li Z-Q. Failure Mechanism of Steep Rock Slope Under the Mining Activities and Rainfall: A Case Study. Water. 2026; 18(1):56. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010056

Chicago/Turabian StyleNing, Kai, and Zhi-Qiang Li. 2026. "Failure Mechanism of Steep Rock Slope Under the Mining Activities and Rainfall: A Case Study" Water 18, no. 1: 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010056

APA StyleNing, K., & Li, Z.-Q. (2026). Failure Mechanism of Steep Rock Slope Under the Mining Activities and Rainfall: A Case Study. Water, 18(1), 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010056