Evaluating the Performance of Infiltration Models Under Semi-Arid Conditions: A Case Study from the Oum Zessar Watershed, Tunisia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

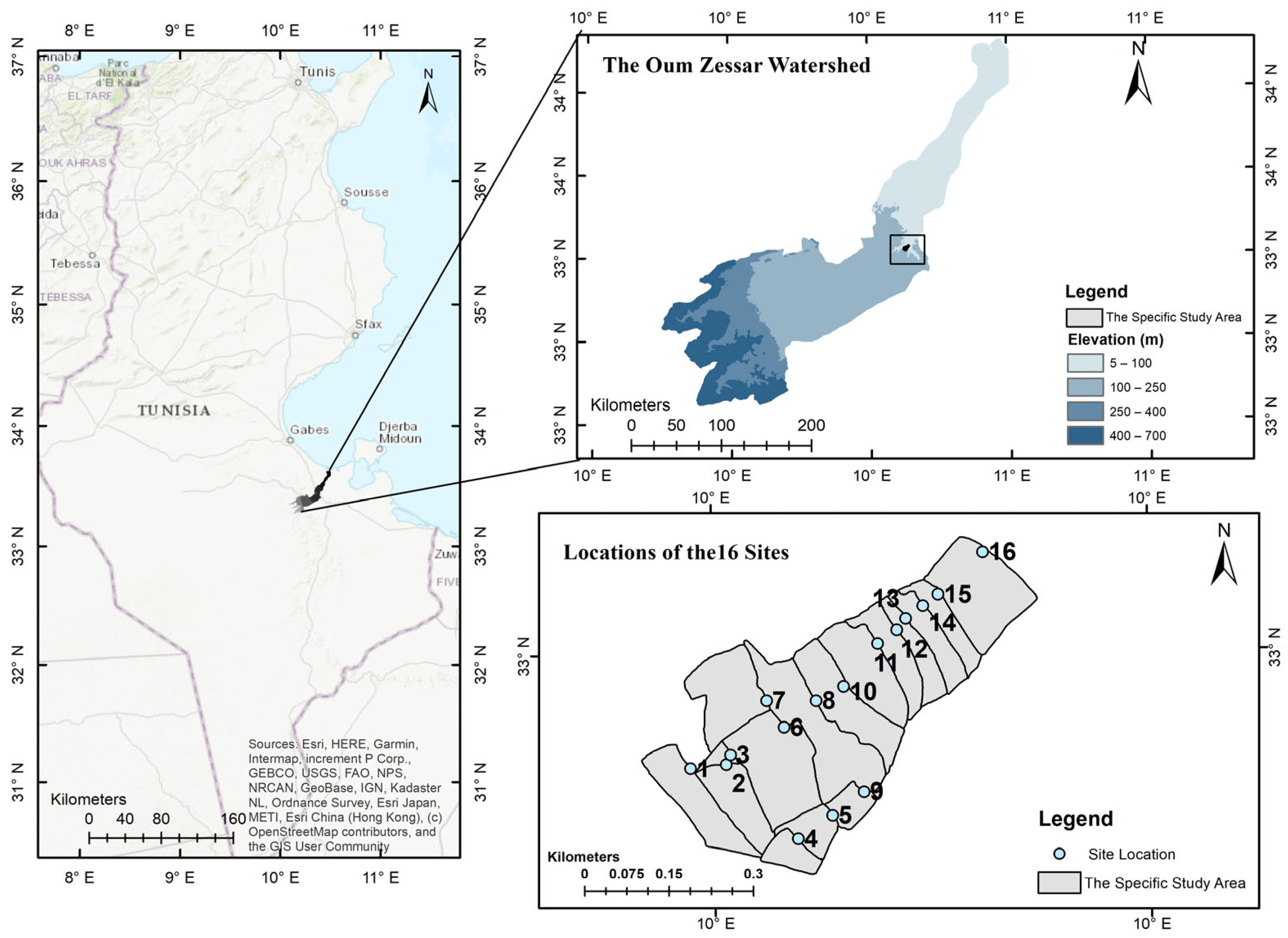

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Infiltration Measurements

2.3. Infiltration Rates: Prediction Models

2.4. Model Accuracy Evaluation

2.5. Statistical Analysis

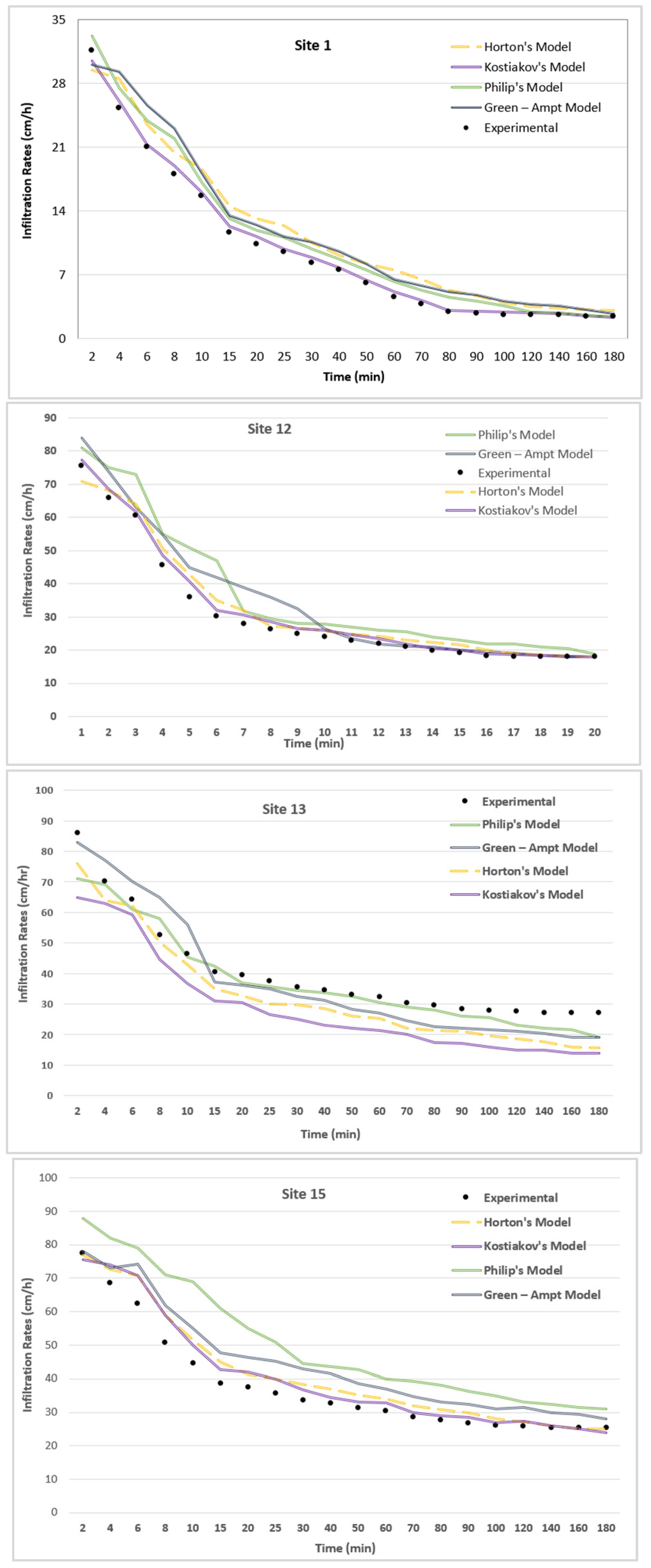

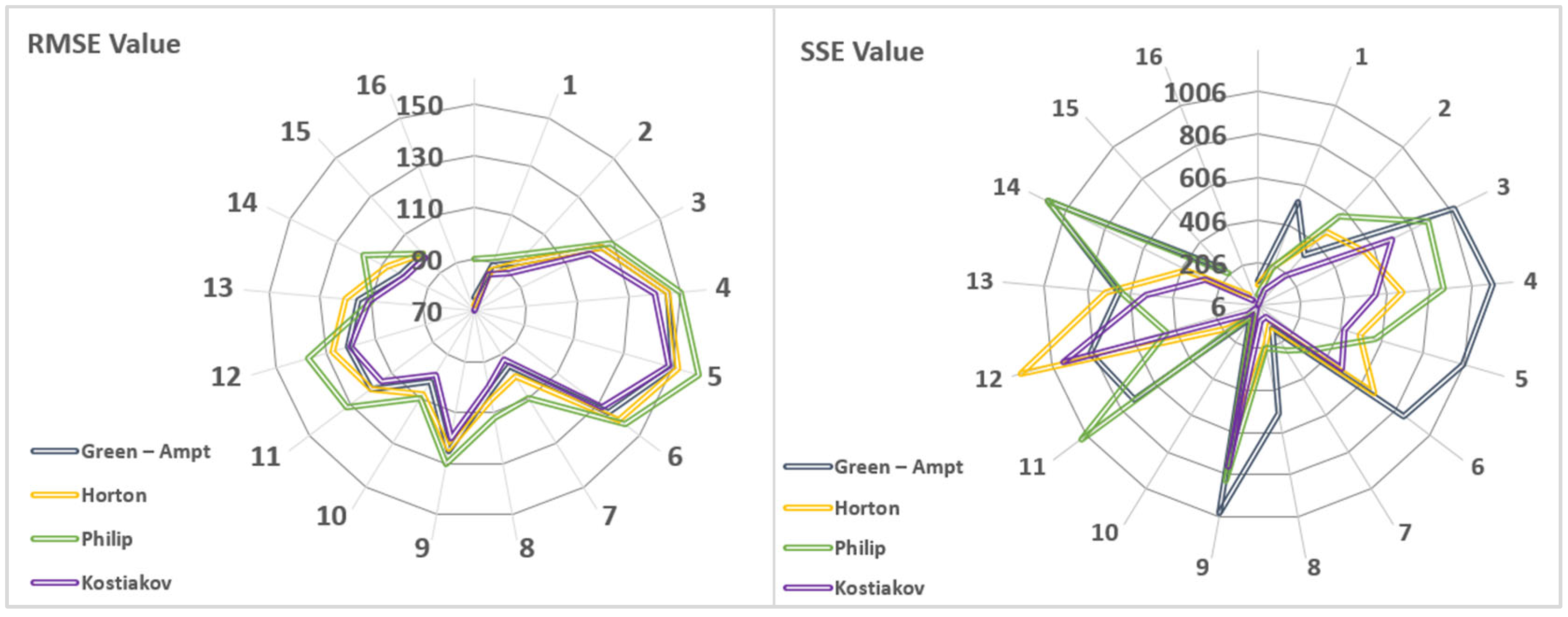

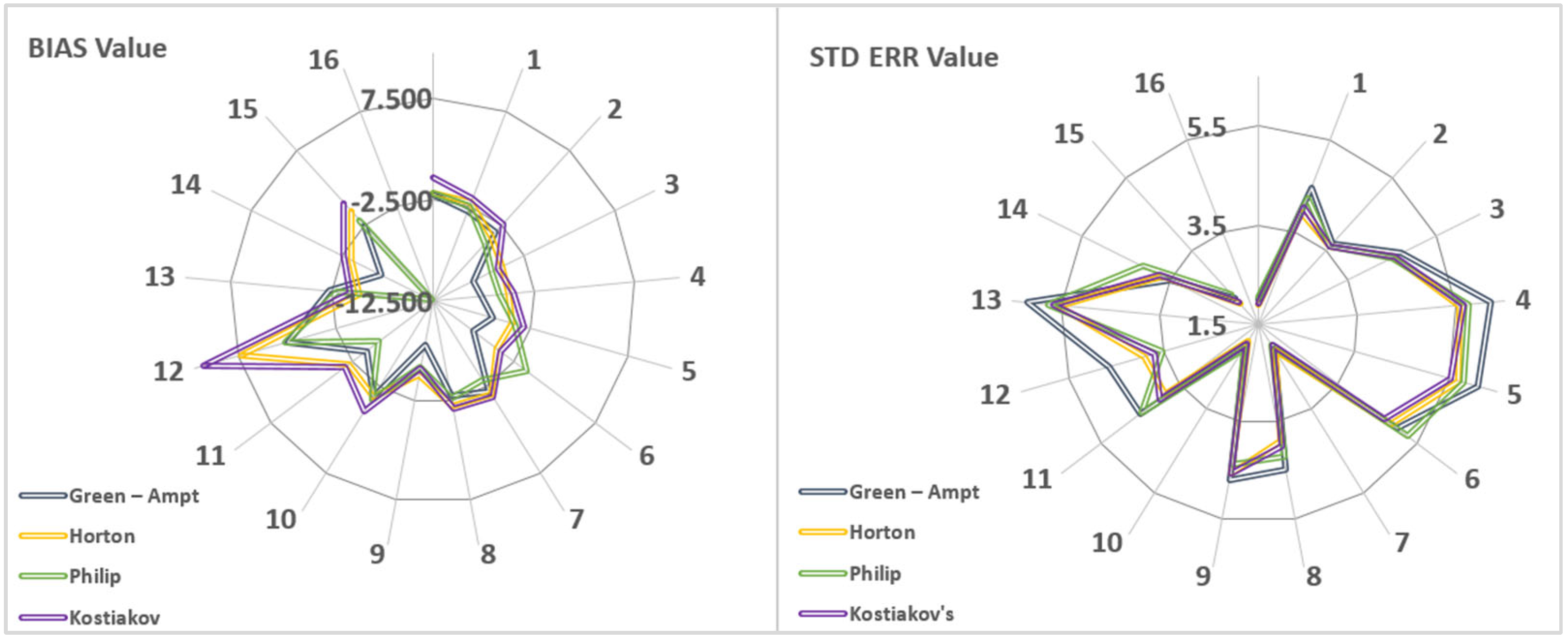

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xia, Q.; Han, H.; Xiong, J.; Zheng, C.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, H.; Zhao, Q. Research Progress of Soil Water Infiltration. E3S Web Conf. 2020, 189, 01006. [Google Scholar]

- Harisuseno, D.; Cahya, E.N. Determination of soil infiltration rate equation based on soil properties using multiple linear regression. J. Water Land Dev. 2020, 47, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adham, A.; Abed, R.; Mahdi, K.; Hassan, W.H.; Riksen, M.; Ritsema, C. Rainwater catchment system reliability analysis for Al Abila Dam in Iraq’s western desert. Water 2023, 15, 944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, R.E. The role of infiltration in the hydrologic cycle. Eos Trans. Am. Geophys. Union 1933, 14, 446–460. [Google Scholar]

- Feki, M.; Ravazzani, G.; Ceppi, A.; Milleo, G.; Mancini, M. Impact of infiltration process modeling on soil water content simulations for irrigation management. Water 2018, 10, 850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patle, G.T.; Sikar, T.T.; Rawat, K.S.; Singh, S.K. Estimation of infiltration rate from soil properties using regression model for cultivated land. Geol. Ecol. Landsc. 2019, 3, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakwan, M.; Niazkar, M. A comparative analysis of data-driven empirical and artificial intelligence models for estimating infiltration rates. Complexity 2021, 1, 9945218. [Google Scholar]

- Angelaki, A.; Sihag, P.; Sakellariou-Makrantonaki, M.; Tzimopoulos, C. The effect of sorptivity on cumulative infiltration. Water Supply 2021, 21, 606–614. [Google Scholar]

- Sharief, S.M.; Zakwan, M.; Farhana, S.N. Estimation of Infiltration Rate using a Nonlinear Regression Model. J. Water Manag. Model. 2023, 31, C509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.W.; Chen, S.K.; Jou, S.W.; Kuo, S.F. Estimation of the infiltration rate of a paddy field in Yun-Lin, Taiwan. Agric. Syst. 2001, 68, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, G.A.; Talaat, A.M.; Zawe, C. Assessment of Infiltration Rate for Sustainability of Reclaimed Area in Harare Region-Zimbabwe. Middle East J. 2016, 5, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Kebede, M.M.; Kumar, M.; Mekonnen, M.M.; Clement, T.P. Enhancing groundwater recharge through Nature-Based Solutions: Benefits and barriers. Hydrology 2024, 11, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abed, R.; Adham, A.; Allawi, M.F.; Ritsema, C. Potential impacts of climate change on the Al Abila Dam in the Western Desert of Iraq. Hydrology 2023, 10, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, W.H.; Ampt, G.A. Studies on Soil Phyics. J. Agric. Sci. 1911, 4, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostiakov, A.N. On the Dynamics of the Coefficient of Water-Percolation in Soils and on the Necessity of Studying It from a Dynamic Point of View for Purposes of Amelioration. 1932, pp. 17–21. Available online: https://scispace.com/papers/on-the-dynamics-of-the-coefficient-of-water-percolation-in-k4vcanqlg0?citations_page=30 (accessed on 18 December 2025).

- Horton, R.E. The interpretation and application of runoff plat experiments with reference to soil erosion problems. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1939, 3, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philip, J.R. The theory of infiltration: 1. The infiltration equation and its solution. Soil Sci. 1957, 83, 345–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghiabi, A.H.; Abedi-Koupai, J.; Heidarpour, M.; Mohammadzadeh-Habili, J. A new method for estimating the parameters of Kostiakov and modified Kostiakov infiltration equations. World Appl. Sci. J. 2011, 15, 129–135. [Google Scholar]

- Adham, A.; Seeyan, S.; Abed, R.; Mahdi, K.; Riksen, M.; Ritsema, C. Sustainability of the Al-Abila Dam in the western desert of Iraq. Water 2022, 14, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogbe, V.B.; Jayeoba, O.J.; Ode, S.O. Comparison of four soil infiltration models on a sandy soil in Lafia, Southern Guinea Savanna Zone of Nigeria. Prod. Agric. Technol. 2011, 7, 116–126. [Google Scholar]

- Oku, E.; Aiyelari, A. Predictability of Philip and Kostiakov infiltration models under inceptisols in the humid forest zone, Nigeria. Agric. Nat. Resour. 2011, 45, 594–602. [Google Scholar]

- Adindu Ruth, U.; Igbokwe Kelechi, K.; Dike Ijeoma, I. Philip model capability to estimate infiltration for solis of Aba, Abia State. J. Earth Sci. Geotech. Eng. 2015, 5, 63–68. [Google Scholar]

- Sreejani, T.P.; Abhishek, D.; Srinivas Rao, G.V.; Abbulu, Y. A study on infiltration characteristics of soils at Andhra university campus, Visakhapatnam. Int. J. Environ. Res. Dev. 2017, 7, 29–44. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, B.; Sihag, P.; Singh, K. Comparison of infiltration models in NIT Kurukshetra campus. Appl. Water Sci. 2018, 8, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A.; Ofosu, A.; Emmanuel, A.; De-Graft, A.; Ayine, A.; Asare, A.; Alexander, A. Comparison and Estimation of Four Infiltration Models. Open J. Soil Sci. 2020, 10, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utin, U.E.; Oguike, P.C. Evaluation of Philip’s and Kostiakov’s infiltration models on soils derived from three parent materials in Akwa Ibom state, Nigeria. J. Sci. Eng. Res. 2018, 5, 79–87. [Google Scholar]

- Mahapatra, S.; Jha, M.K.; Biswal, S.; Senapati, D. Assessing variability of infiltration characteristics and reliability of infiltration models in a tropical sub-humid region of India. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamoud, Y.M. Evaluating the Green and Ampt infiltration parameter values for tilled and crusted soils. J. Hydrol. 1991, 123, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruth, U.A.; Kelechi, K.I.; Timothy, O.C.; Ike-Amadi, C.A. Application Kostiakov’s Infiltration Model on The Soils of Umudike, Abia State-Nigeria. Am. J. Environ. Eng. 2014, 4, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Ghazouani, W.; Zairi, A.; Slatni, A. Influence of tillage systems on soil physical properties and water infiltration in semi-arid Tunisia. Soil Tillage Res. 2022, 219, 105334. [Google Scholar]

- Ben Slimane, A.; Nasr, Z.; Bouhlila, R.; El Ayeb, N. Evaluation of hydraulic conductivity and water retention properties of Tunisian soils. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2021, 35, 100818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdi, R.; Jebari, S.; Berndtsson, R.; Bahri, A.; Boufaroua, M. Assessment of surface runoff and soil erosion in semi-arid Tunisia using the SWAT model. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2015, 70, 334–344. [Google Scholar]

- Adham, A.; Riksen, M.; Abed, R.; Shadeed, S.; Ritsema, C. Assessing suitable techniques for rainwater harvesting using analytical hierarchy process (AHP) methods and GIS techniques. Water 2022, 14, 2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouessar, M. Hydrological Impacts of Rainwater Harvesting in Wadi Oum Zessar Watershed (Southern Tunisia); Ghent University: Ghent, Belgium, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Abdeladhim, M.A.; Fleskens, L.; Baartman, J.; Sghaier, M.; Ouessar, M.; Ritsema, C.J. Generation of potential sites for sustainable water harvesting techniques in Oum Zessar watershed, South East Tunisia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Bosch, S.; Hessel, R.; Ouessar, M.; Zerrim, A.; Ritsema, C.J. Determining the Saturated Vertical Hydraulic Conductivity of Retention Basins in the Oum Zessar Watershed, Soutern Tunisia. 2014. Available online: https://edepot.wur.nl/332036 (accessed on 18 December 2025).

- Abdullah, O.S.; Kamel, A.H.; Khalil, W.H.; Al-damook, A. Estimation of Hydropower Harvesting from the Hydraulic Structures on Rivers: Ramadi Barrage, Iraq as a Case Study. Iraqi J. Civ. Eng. 2020, 14, 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Autovino, D.; Bagarello, V.; Caltabellotta, G.; Varadi, F.K.; Zanna, F. One-dimensional infiltration in a layered soil measured in the laboratory with the mini-disk infiltrometer. J. Hydrol. Hydromech. 2024, 72, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adham, A.; Riksen, M.; Ouessar, M.; Abed, R.; Ritsema, C. Development of methodology for existing rainwater harvesting assessment in (semi-) arid regions. In Water and Land Security in Drylands: Response to Climate Change; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 171–184. [Google Scholar]

- Sayl, K.N.; AL-Ani, A.; Oliwi, S. Hydrologic Study for Iraqi Western Desert to Assessment of Water Harvesting Projects. Iraqi J. Civ. Eng. 2012, 7, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukata, S.U.; Akintoye, O.A.; Digha, O.N.; Alade, A.; Asiyanbi, A. The transformation of Kostiakov’s (1932) infiltration equation on the infiltration rate of forest land cover in Biase, Cross River State, Nigeria. IOSR J. Environ. Sci. Toxicol. Food Technol. 2015, 9, 47–50. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.H. Model Selection in High-Dimensional Regression. In Wiley StatsRef: Statistics Reference Online; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; Volume 14, pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Handbook on Constructing Composite Indicators: Methodology and User Guide; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

| Site# | Elevation (m) | Latitude (Degree) | Longitude (Degree) | Soil Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 114.80 | 33.423168 | 10.374534 | Loam |

| 2 | 117.20 | 33.423225 | 10.375217 | Loam |

| 3 | 110.12 | 33.423382 | 10.375302 | Loam |

| 4 | 119.05 | 3.616522 | 10.152355 | Clay loam |

| 5 | 121.77 | 33.422394 | 10.377235 | Sand |

| 6 | 114.40 | 33.423813 | 10.376327 | Sandy loam |

| 7 | 116.37 | 33.424246 | 10.376001 | Sandy clay loam |

| 8 | 113.22 | 33.424234 | 10.376950 | Clay loam |

| 9 | 103.99 | 33.422767 | 10.377845 | Clay loam |

| 10 | 88.93 | 33.424457 | 10.377475 | Sandy clay loam |

| 11 | 111.96 | 33.425137 | 10.378138 | Silty clay loam |

| 12 | 107.38 | 33.425195 | 10.378435 | Sandy loam |

| 13 | 106.04 | 33.425534 | 10.378678 | Sand |

| 14 | 102.64 | 33.425735 | 10.379008 | Sandy loam |

| 15 | 109.14 | 33.425916 | 10.379304 | Sandy loam |

| 16 | 108.15 | 33.426585 | 10.380165 | Silty clay loam |

| Time (min) | Site (1) | Site (2) | Site (3) | Site (4) | Site (5) | Site (6) | Site (7) | Site (8) | Site (9) | Site (10) | Site (11) | Site (12) | Site (13) | Site (14) | Site (15) | Site (16) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 31.6 | 60.1 | 55.3 | 70.3 | 85.3 | 83 | 75.3 | 41 | 62.2 | 73.55 | 41.1 | 75.7 | 86 | 82.8 | 77.5 | 44.1 |

| 4 | 25.3 | 50.3 | 46.3 | 65 | 82 | 81 | 70 | 35.3 | 52.4 | 68.25 | 34.8 | 65.9 | 70.3 | 79.5 | 68.5 | 37.8 |

| 6 | 21 | 45.1 | 40.2 | 56 | 72 | 79 | 61 | 31 | 47.2 | 59.25 | 30.5 | 60.7 | 64.2 | 69.5 | 62.4 | 33.5 |

| 8 | 18 | 30 | 28.6 | 50.3 | 64.3 | 62.3 | 55.3 | 28 | 32.1 | 53.55 | 27.5 | 45.6 | 52.6 | 61.8 | 50.8 | 30.5 |

| 10 | 15.6 | 20.5 | 22.4 | 45.7 | 56.2 | 55.1 | 50 | 25 | 22.6 | 48.95 | 25.1 | 36.1 | 46.4 | 53.7 | 44.6 | 28.1 |

| 15 | 11.6 | 14.6 | 16.5 | 38.2 | 46.8 | 47 | 43 | 21.6 | 16.7 | 41.45 | 21.1 | 30.2 | 40.5 | 44.3 | 38.7 | 24.1 |

| 20 | 10.3 | 12.3 | 15.4 | 32.6 | 40.1 | 42 | 37 | 20 | 14.4 | 35.85 | 19.8 | 27.9 | 39.4 | 37.6 | 37.6 | 22.8 |

| 25 | 9.5 | 10.8 | 13.6 | 29.3 | 35 | 35 | 34 | 19.2 | 12.9 | 32.55 | 19 | 26.4 | 37.6 | 32.5 | 35.8 | 22 |

| 30 | 8.3 | 9.3 | 11.5 | 24.5 | 32.5 | 31 | 29 | 18.2 | 11.4 | 27.75 | 17.8 | 24.9 | 35.5 | 30 | 33.7 | 20.8 |

| 40 | 7.5 | 8.5 | 10.6 | 21.7 | 28.5 | 29 | 26.3 | 17.4 | 10.6 | 24.95 | 17 | 24.1 | 34.6 | 26 | 32.8 | 20 |

| 50 | 6.1 | 7.4 | 9.1 | 18.6 | 22.6 | 23.1 | 23.1 | 16.3 | 9.5 | 21.85 | 15.6 | 23 | 33.1 | 20.1 | 31.3 | 18.6 |

| 60 | 4.5 | 6.3 | 8.3 | 15.4 | 19.3 | 19.3 | 20.3 | 14.8 | 8.4 | 18.65 | 14 | 21.9 | 32.3 | 16.8 | 30.5 | 17 |

| 70 | 3.8 | 5.4 | 6.4 | 13.2 | 17.1 | 17.1 | 18.2 | 13.7 | 7.5 | 16.45 | 13.3 | 21 | 30.4 | 14.6 | 28.6 | 16.3 |

| 80 | 2.9 | 4.3 | 5.6 | 10.3 | 15.3 | 15.4 | 15.4 | 12.9 | 6.4 | 13.55 | 12.4 | 19.9 | 29.6 | 12.8 | 27.8 | 15.4 |

| 90 | 2.7 | 3.6 | 4.5 | 8.9 | 13.6 | 13.1 | 14 | 12.3 | 5.7 | 12.15 | 12.2 | 19.2 | 28.5 | 11.1 | 26.7 | 15.2 |

| 100 | 2.6 | 2.7 | 3.8 | 7.6 | 11.2 | 11.2 | 12.5 | 11.6 | 4.8 | 10.85 | 12.1 | 18.3 | 27.8 | 8.7 | 26 | 15.1 |

| 120 | 2.6 | 2.5 | 3.6 | 6.5 | 9.5 | 9.3 | 11.8 | 11.1 | 4.5 | 9.75 | 12.1 | 18 | 27.6 | 7 | 25.8 | 15.1 |

| 140 | 2.6 | 2.5 | 3.2 | 6.5 | 8.7 | 8.9 | 11.4 | 10.2 | 4.5 | 9.75 | 12.1 | 18 | 27.2 | 6.2 | 25.4 | 15.1 |

| 160 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 3.2 | 6.4 | 8.7 | 8.9 | 11.4 | 10.2 | 4.5 | 9.65 | 12 | 18 | 27.2 | 6.2 | 25.4 | 15 |

| 180 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 3.2 | 6.4 | 8.7 | 8.9 | 11.4 | 10.2 | 4.5 | 9.65 | 12 | 18 | 27.2 | 6.2 | 25.4 | 15 |

| CIR cm/h | 2.4 | 2.5 | 3.2 | 6.4 | 8.7 | 8.9 | 11.4 | 10.2 | 4.5 | 9.65 | 12 | 18 | 27.2 | 6.2 | 25.4 | 15 |

| Site # | Constant Infiltration Rate (cm/h) | Horton | Kostiakov | Philip | Green–Ampt | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kh (1/h) | A (cm/h(1–b)) | b | S | k (cm/h) | m (cm/h) | N (cm) | ||

| Site 1 | 2.40 | 1.90 | 6.75 | 0.54 | 8.10 | 1.01 | 0.02 | 6.30 |

| Site 2 | 2.50 | 1.32 | 6.33 | 0.56 | 7.86 | 1.98 | 0.02 | 5.02 |

| Site 3 | 3.20 | 1.12 | 7.14 | 0.61 | 9.25 | 2.35 | 0.02 | 7.12 |

| Site 4 | 6.40 | 0.98 | 7.05 | 0.65 | 9.75 | 3.15 | 0.02 | 6.12 |

| Site 5 | 8.70 | 0.89 | 7.87 | 0.67 | 10.24 | 4.12 | 1.01 | 11.25 |

| Site 6 | 8.90 | 0.70 | 8.10 | 0.74 | 11.30 | 4.60 | 2.10 | 13.20 |

| Site 7 | 11.40 | 0.69 | 8.25 | 0.73 | 12.10 | 5.10 | 2.70 | 14.10 |

| Site 8 | 10.20 | 0.87 | 9.30 | 0.75 | 14.20 | 5.90 | 2.50 | 13.70 |

| Site 9 | 4.50 | 1.84 | 6.02 | 0.61 | 8.90 | 2.01 | 0.03 | 8.50 |

| Site 10 | 9.65 | 0.90 | 6.50 | 0.57 | 7.80 | 1.80 | 0.60 | 6.80 |

| Site 11 | 12.00 | 0.65 | 7.10 | 0.59 | 8.30 | 2.10 | 2.10 | 13.10 |

| Site 12 | 18.00 | 0.51 | 7.80 | 0.65 | 11.10 | 4.10 | 2.30 | 13.60 |

| Site 13 | 27.20 | 0.32 | 8.30 | 0.70 | 9.50 | 2.90 | 1.50 | 8.60 |

| Site 14 | 6.20 | 0.97 | 5.60 | 0.51 | 10.30 | 4.00 | 1.30 | 7.90 |

| Site 15 | 25.40 | 0.30 | 5.30 | 0.49 | 7.80 | 1.90 | 1.80 | 8.60 |

| Site 16 | 15.00 | 0.57 | 9.20 | 0.71 | 8.50 | 1.12 | 2.30 | 8.10 |

| Site Number | Constant Infiltration Rate (cm/h) | Horton’s Model | Kostiakov’s Model | Philip’s Model | Green–Ampt Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site 1 | 2.4 | 3.1 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 2.7 |

| Site 2 | 2.5 | 2.3 | 2.5 | 2.1 | 1.9 |

| Site 3 | 3.2 | 3.4 | 3.1 | 3.6 | 3.1 |

| Site 4 | 6.4 | 9.3 | 8.1 | 8.3 | 9.6 |

| Site 5 | 8.7 | 9.5 | 8.1 | 9.3 | 9.0 |

| Site 6 | 8.9 | 10.1 | 7.8 | 7.5 | 9.1 |

| Site 7 | 11.4 | 7.6 | 10.2 | 5.0 | 9.6 |

| Site 8 | 10.2 | 10.1 | 12.3 | 14.1 | 9.3 |

| Site 9 | 4.5 | 4.212 | 4.5 | 4.31 | 3.916 |

| Site 10 | 9.65 | 12.86 | 11.64 | 14.1 | 14.3 |

| Site 11 | 12.0 | 12.1 | 10.0 | 10.2 | 11.8 |

| Site 12 | 18.0 | 17.9 | 17.9 | 19.0 | 17.9 |

| Site 13 | 27.2 | 15.6 | 13.8 | 19.0 | 19.1 |

| Site 14 | 6.2 | 7.2 | 5.0 | 3.3 | 1.0 |

| Site 15 | 25.4 | 25.0 | 24.0 | 31.0 | 28.0 |

| Site 16 | 15.0 | 11.8 | 11.0 | 11.0 | 11.0 |

| Model | NI RMSE | NI NSE | NI SSE | NI CORR | NI STD.ERR | NI Bias | MPI | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kostiakov | 0.253529 | 0.788109 | 1 | 0.614147 | 1 | 0.637677 | 0.119263 | 1 |

| Horton | 0 | 1 | 0.954627 | 1 | 0.97216708 | 1 | 0.136855 | 2 |

| Philip | 0.764953 | 0.302546 | 0.301205 | 0.315482 | 0.49396129 | 0.164421 | 0.065071 | 3 |

| Green–Ampt | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.027778 | 4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Abed, R.; Adham, A.; Shareef, M.E.; Riksen, M. Evaluating the Performance of Infiltration Models Under Semi-Arid Conditions: A Case Study from the Oum Zessar Watershed, Tunisia. Water 2026, 18, 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010055

Abed R, Adham A, Shareef ME, Riksen M. Evaluating the Performance of Infiltration Models Under Semi-Arid Conditions: A Case Study from the Oum Zessar Watershed, Tunisia. Water. 2026; 18(1):55. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010055

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbed, Rasha, Ammar Adham, Mohammad Esam Shareef, and Michel Riksen. 2026. "Evaluating the Performance of Infiltration Models Under Semi-Arid Conditions: A Case Study from the Oum Zessar Watershed, Tunisia" Water 18, no. 1: 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010055

APA StyleAbed, R., Adham, A., Shareef, M. E., & Riksen, M. (2026). Evaluating the Performance of Infiltration Models Under Semi-Arid Conditions: A Case Study from the Oum Zessar Watershed, Tunisia. Water, 18(1), 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010055