Phytoplankton Community Shifts Under Nutrient Imbalance in the Yellow River Estuary and Adjacent Coastal Waters

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Field Sampling and Laboratory Analysis

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

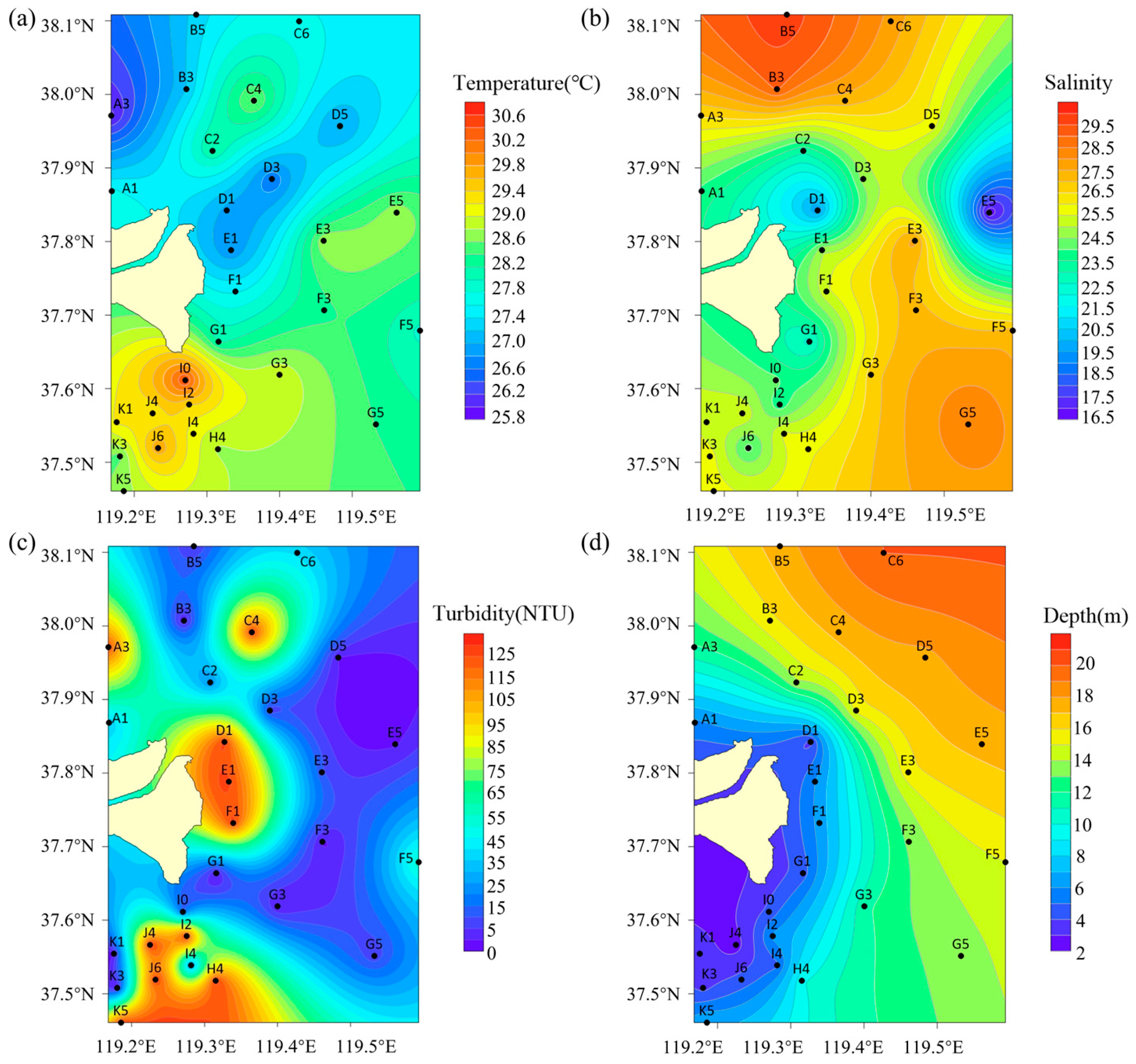

3.1. Physical Conditions

3.2. Spatial Variation in Phytoplankton Composition

3.3. Spatial Distribution of Phytoplankton Diversity

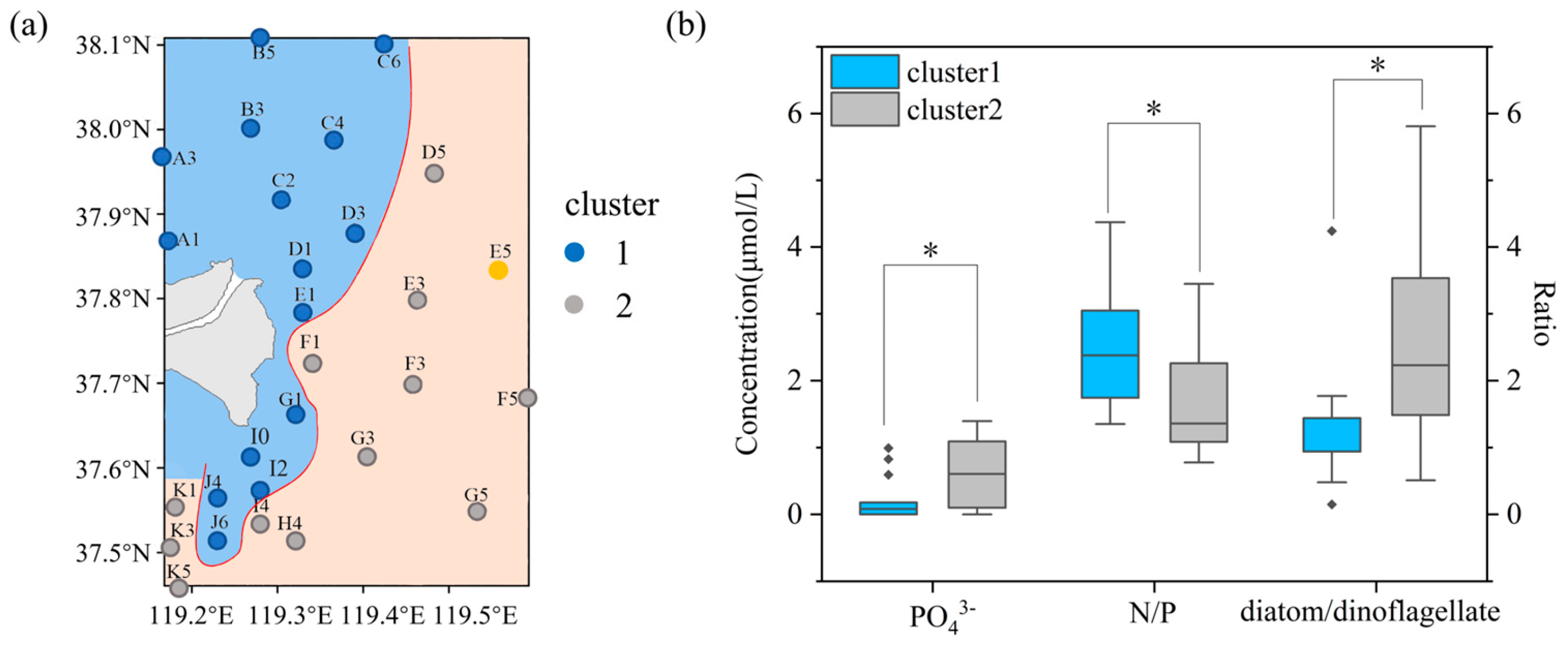

3.4. Distinct Zones in Diatom and Dinoflagellate Proportions

3.5. Difference in Nutrient Structures of Two Zones

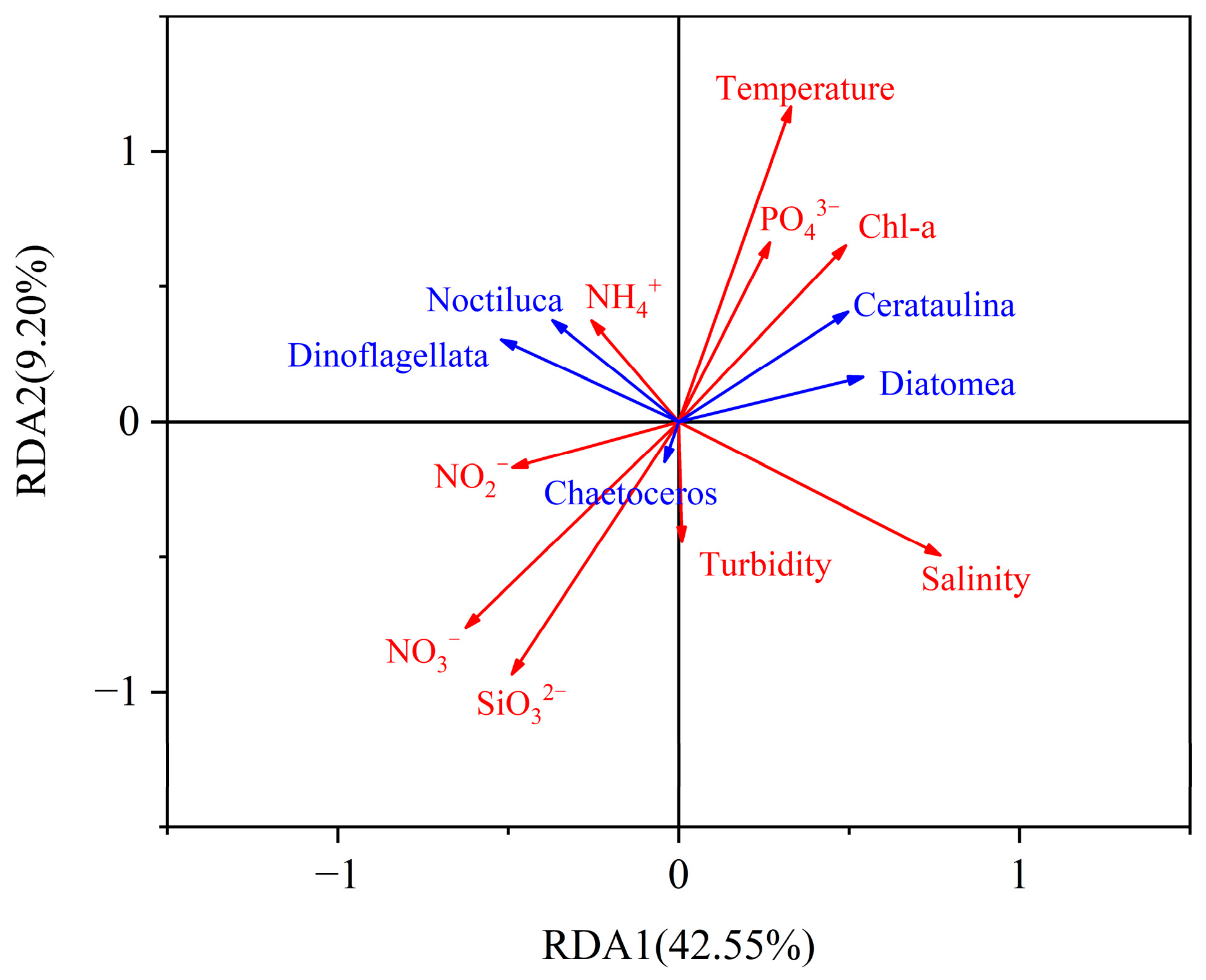

3.6. Controlling Factors of Phytoplankton Taxa

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| YRE | Yellow River Estuary |

| WSRS | Water-Sediment Regulation Scheme |

| RDA | Redundancy analysis |

| ASVs | Amplicon sequence variants |

References

- Kwon, E.Y.; Sreeush, M.G.; Timmermann, A.; Karl, D.M.; Church, M.J.; Lee, S.-S.; Yamaguchi, R. Nutrient uptake plasticity in phytoplankton sustains future ocean net primary production. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eadd2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akter, S.; Nama, S.; Wodeyar, K.A.; Deshmukhe, G.; Nayak, B.B.; Jaiswar, A.K.; Landge, A.T.; Ramteke, K. Unravelling tropical estuary health through a multivariate analysis of spatiotemporal phytoplankton diversity and community structure in relation to environmental interactions. Aquat. Sci. 2024, 86, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ptacnik, R.; Solimini, A.G.; Andersen, T.; Tamminen, T.; Brettum, P.; Lepisto, L.; Willen, E.; Rekolainen, S. Diversity predicts stability and resource use efficiency in natural phytoplankton communities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 5134–5138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Li, F.; Lv, Q.; Wang, Y.; Yu, J.; Gao, Y.; Ren, Z.; Zhang, X.; Lv, Z. Impact of the Water-Sediment Regulation Scheme on the phytoplankton community in the Yellow River estuary. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 294, 126291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Li, F.; Wei, J.; Li, S.; Lv, Z.; Gao, Y.; Cong, X. Community characteristics of macrobenthos in the Huanghe (Yellow River) Estuary during water and sediment discharge regulation. Acta Oceanol. Sin. 2016, 35, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howarth, R.W.; Marino, R. Nitrogen as the limiting nutrient for eutrophication in coastal marine ecosystems: Evolving views over three decades. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2006, 51, 364–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, F.; Tan, L.; Wang, J. Nutrients structure changes impact the competition and succession between diatom and dinoflagellate in the East China Sea. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 574, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, R.; Cao, Z.; Ismar-Rebitz, S.M.H.; Sommer, U.; Zhang, H.; Ding, Y.; Zhao, M. Responses of Marine Diatom-Dinoflagellate Competition to Multiple Environmental Drivers: Abundance, Elemental, and Biochemical Aspects. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 731786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, J.W.; Schulz, I.K.; Rowe, K.A.; Dobbins, W.; Winding, M.H.S.; Sejr, M.K.; Duarte, C.M.; Agusti, S. Silicic acid limitation drives bloom termination and potential carbon sequestration in an Arctic bloom. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 8149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondoc, K.G.V.; Heuschele, J.; Gillard, J.; Vyverman, W.; Pohnert, G. Selective silicate-directed motility in diatoms. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Hu, Z.; Tang, Y.Z. Plasticity and Multiplicity of Trophic Modes in the Dinoflagellate Karlodinium and Their Pertinence to Population Maintenance and Bloom Dynamics. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mena, C.; Long, M.; Lorand, O.; Malestroit, P.; Rabiller, E.; Maguer, J.-F.; L’Helguen, S.; De Gioux, A.R. Impact of light and nutrient availability on the phagotrophic activity of harmful bloom-forming dinoflagellates. J. Plankton Res. 2024, 47, fbae038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weng, C.; Ding, D.; Yang, Q.; Zhu, L.; Sun, J.; Qu, K.; Cui, Z.; Wei, Y. Significance of temperature and salinity in the dynamics of diatoms and dinoflagellates along the coastal Yellow Sea. Prog. Oceanogr. 2025, 234, 103478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.; Jiang, C.; Weng, X.; Zhang, M. Influence of Salinity Gradient Changes on Phytoplankton Growth Caused by Sluice Construction in Yongjiang River Estuary Area. Water 2020, 12, 2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.Y.; Guo, Y.Y.; Liu, H.J.; Zhang, G.C.; Zhang, X.D.; Thangaraj, S.; Sun, J. Water quality shifts the dominant phytoplankton group from diatoms to dinoflagellates in the coastal ecosystem of the Bohai Bay. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2022, 183, 114078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, F.T.; Zhu, Z.Y.; Ge, J.Z.; Deng, B.; Du, J.Z.; Zhang, J. Reconstruction of the main phytoplankton population off the Changjiang Estuary in the East China Sea and its assemblage shift in recent decades: From observations to simulation. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2022, 178, 113638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klais, R.; Tamminen, T.; Kremp, A.; Spilling, K.; Olli, K. Decadal-Scale Changes of Dinoflagellates and Diatoms in the Anomalous Baltic Sea Spring Bloom. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e21567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.M.; Li, L.W.; Zhang, G.L.; Liu, Z.; Yu, Z.G.; Ren, J.L. Impacts of human activities on nutrient transports in the Huanghe (Yellow River) estuary. J. Hydrol. 2012, 430, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Sheng, L. Model of water-sediment regulation in Yellow River and its effect. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2011, 54, 924–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B. Research summarize on dynamic mechanisms of geomorphological evolution in world estuary delta. Shanghai Land Resour. 2020, 41, 93–97. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=zYSMMY9t1scDx8GkwJV14eYnw655iyHErd3umSYA-iZ65WrwDFUf4CCX3AXXNxmCp4_LyqxjtCG3vgtyuK1b-R6u31dcZLOmaVUrsXIojfD-l5EAkPIM-_WrXa1c3r8ahMGk2YM52LCEWaDpPVlQnlZWfy7iHdZEV9CPLpcVMdNvu98xFx8SaHPlsQwy33Zc&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- Qiao, S.; Yang, Y.; Xu, B.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, M.; Li, F.; Yu, H. How the Water-Sediment Regulation Scheme in the Yellow River affected the estuary ecosystem in the last 10 years? Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 927, 172002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufrene, M.; Legendre, P. Species assemblages and indicator species: The need for a flexible asymmetrical approach. Ecol. Monogr. 1997, 67, 345–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Qin, H.; Qiao, S.; Li, F.; Shi, H.; Zhang, X. Effect of the yellow river runoff into the sea on the salinity of the waters near the estuary. Coast. Eng. 2022, 41, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justic, D.; Rabalais, N.N.; Turner, R.E. Stoichiometric nutrient balance and origin of coastal eutrophication. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 1995, 30, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, D.M.; Treguer, P.; Brzezinski, M.A.; Leynaert, A.; Queguiner, B. Production and dissolution of biogenic silica in the ocean-revised global estimates, comparison with regional data and relationship to biogenic sedimentation. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 1995, 9, 359–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.; Qin, H.; Ma, H.; Xu, Z.; Lv, H.; Liang, S. Temporospatial distribution of phosphorus and response of phytoplankton to low phosphorus stress in the Yellow River estuary and Laizhou Bay. Period. Ocean. Univ. China 2023, 53, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Dassow, P.; Mikhno, M.; Percopo, I.; Orellana, V.R.; Aguilera, V.; Alvarez, G.; Araya, M.; Cornejo-Guzman, S.; Llona, T.; Mardones, J.I.; et al. Diversity and toxicity of the planktonic diatom genus Pseudo-nitzschia from coastal and offshore waters of the Southeast Pacific, including Pseudo-nitzschia dampieri sp. nov. Harmful Algae 2023, 130, 102520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappell, P.D.; Whitney, L.P.; Haddock, T.L.; Menden-Deuer, S.; Roy, E.G.; Wells, M.L.; Jenkins, B.D. Thalassiosira spp. community composition shifts in response to chemical and physical forcing in the northeast Pacific Ocean. Front. Microbiol. 2013, 4, 54400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, T.; Thilagaraj, A.V.; Mouradov, D.; Piola, R.; Grandison, C.; Gordon, M.; Shimeta, J.; Mouradov, A. Diversity of dinoflagellate assemblages in coastal temperate and offshore tropical waters of Australia. BMC Ecol. Evol. 2021, 21, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Duan, H.; Bi, N.; Yuan, P.; Wang, A.; Wang, H. Interannual and seasonal variation of chlorophyll-a off the Yellow River Mouth (1997–2012): Dominance of river inputs and coastal dynamics. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2016, 183, 402–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, M.; Wang, B.; Xie, L.; Sun, X.; Wei, Q.; Mang, S.; Chen, K. Long-term changes in nutrient regimes and their ecological effects in the Bohai Sea, China. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 146, 562–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, E.S.; del Rio, J.G. Spatial variations of phytoplankton community structure in a highly eutrophicated coast of the Western Mediterranean Sea. Water Sci. Technol. 1995, 32, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Huang, H. Advances in the study of biodiversity of phytoplankton and red tide species in China (I): The Bohai Sea. Oceanol. Limnol. Sin. 2021, 52, 346–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; He, J.; Cheng, L.; Liu, N.; Fu, P.; Wang, N.; Jiang, X.; Sun, S.; Zhang, J. Long-term response of plankton assemblage to differentiated nutrient reductions in Laizhou Bay, China. J. Sea Res. 2024, 198, 102490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Qi, Y.; Chen, X.; Chen, Y.; Su, D.; Yuan, X.; Klippel-Cooper, J. Response of phytoplankton communities to environmental changes in the Bohai Sea in late summer (2011–2020). Acta Oceanol. Sin. 2024, 43, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.Y.; Bi, R.; Gao, J.W.; Zhang, H.L.; Li, L.; Ding, Y.; Jin, G.E.; Zhao, M.X. Kuroshio Intrusion Combined with Coastal Currents Affects Phytoplankton in the Northern South China Sea Revealed by Lipid Biomarkers. J. Ocean Univ. China 2023, 22, 576–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Guo, X.; Takeoka, H. Seasonal variations of the Yellow River plume in the Bohai Sea: A model study. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2008, 113, C08046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, C.; Jiang, W.; Pohlmann, T.; Suendermann, J. Hydrography-Physical Description of the Bohai Sea. J. Coast. Res. 2016, 74, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Qiao, L.; Li, G.; Zhong, Y.; Miao, H.; Hu, R. Discontinuity of sediment transport from the Bohai Sea to the open sea dominated by the wind direction. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2023, 293, 108486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.; Lee, C.H.; Kim, Y.B.; Kim, C.H.; Park, C.H.; Baek, S.H. Impacts of stratified water column on summer phytoplankton community structure and dynamics in the East Sea, Korea. Cont. Shelf Res. 2026, 296, 105592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yu, K.; Li, M.; Jiang, H.; Gao, W.; Zhao, J.; Li, K. Diatom-dinoflagellate succession in the Bohai Sea: The role of N/P ratios and dissolved organic nitrogen components. Water Res. 2024, 251, 121150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Achterberg, E.P.; Li, K.; Zhang, J.; Xin, M.; Wang, X. Governance pathway for coastal eutrophication based on regime shifts in diatom-dinoflagellate composition of the Bohai and Baltic Seas. Water Res. 2024, 250, 121042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Yang, Z.; Saito, Y.; Liu, J.P.; Sun, X.; Wang, Y. Stepwise decreases of the Huanghe (Yellow River) sediment load (1950–2005): Impacts of climate change and human activities. Glob. Planet. Change 2007, 57, 331–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bode, A.; Barquero, S.; González, N.; Alvarez-Ossorio, M.T.; Varela, M. Contribution of heterotrophic plankton to nitrogen regeneration in the upwelling ecosystem of A Coruna (NW Spain). J. Plankton Res. 2004, 26, 11–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, M.M.; Barquero, S.; Bode, A.; Fernández, E.; González, N.; Teira, E.; Varela, M. Microplanktonic regeneration of ammonium and dissolved organic nitrogen in the upwelling area of the NW of Spain:: Relationships with dissolved organic carbon production and phytoplankton size-structure. J. Plankton Res. 2003, 25, 719–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, G.T.; Clifford, C.H.; Smith, K.L. Benthic nutrient regeneration and its coupling to primary productivity in coastal waters. Nature 1975, 255, 215–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Gaye, B.; Tang, J.; Luo, Y.; Lahajnar, N.; Daehnke, K.; Sanders, T.; Xiong, T.; Zhai, W.; Emeis, K.-C. Nitrate Regeneration and Loss in the Central Yellow Sea Bottom Water Revealed by Nitrogen Isotopes. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 834953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Zhang, M.; Yin, H. Phosphorus release from the sediment of a drinking water reservoir under the influence of seasonal hypoxia. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 917, 170490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, R.J.K.; Waltham, N.J.; Teasdale, P.R.; Robertson, D.; Welsh, D.T. Short-Term Nitrogen and Phosphorus Release during the Disturbance of Surface Sediments: A Case Study in an Urbanised Estuarine System (Gold Coast Broadwater, Australia). J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2017, 5, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Yu, W.; Chen, B.; Ma, Z.; Chen, G.; Ge, F.; An, S.; Han, W. Imbalanced phytoplankton C, N, P and its relationship with seawater nutrients in Xiamen Bay, China. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 187, 114566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Bi, R.; Sachs, J.P.; Wang, Y.; Ding, Y.; Che, H.; Zhang, J.; Yao, P.; Shi, J.; Zhao, M. Assessing the interaction of oceanic and riverine processes on coastal phytoplankton dynamics in the East China Sea. Mar. Life Sci. Technol. 2025, 7, 157–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Nakano, S.-I. The crucial influence of trophic status on the relative requirement of nitrogen to phosphorus for phytoplankton growth. Water Res. 2022, 222, 118868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Lv, Q.; Lv, Z.; Wang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Ren, Z. Effects of water and sediment regulation scheme on phytoplankton community and abundance in the Yellow River Estuary. Mar. Environ. Sci. 2021, 40, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Sun, J.; Gu, T.; Zhang, G.; Wei, Y. Nutrient ratios driven by vertical stratification regulate phytoplankton community structure in the oligotrophic western Pacific Ocean. Ocean Sci. 2021, 17, 1775–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisinicu, E.; Lazar, L. Assessing the Black Sea Mesozooplankton Community Following the Nova Kakhovka Dam Breach. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraguchi, L.; Kraft, K.; Yloestalo, P.; Kielosto, S.; Haellfors, H.; Tamminen, T.; Seppaelae, J. Trait response of three Baltic Sea spring dinoflagellates to temperature, salinity, and light gradients. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1156487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Chen, M.; Ouyang, W.; Lin, C.; He, M. Fine particle contents in sediment drive silica transport and deposition to the estuary in the turbid river basin. Water Res. 2024, 255, 121464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, B.; Montagna, P.A.; Adams, L. Variations in the release of silicate and orthophosphate along a salinity gradient: Do sediment composition and physical forcing have roles? Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2015, 157, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, H.; Lin, J.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, W.; Li, C. Phytoplankton Blooms off a High Turbidity Estuary: A Case Study in the Changjiang River Estuary. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2019, 124, 8036–8059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Feng, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Bian, Z.; Zhang, F.; Cao, F.; Wu, H.; Wang, Y.P. Light attenuation parameterization in a highly turbid mega estuary and its impact on the coastal planktonic ecosystem. Front. Mar. Sci. 2024, 11, 1486261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carstensen, J.; Klais, R.; Cloern, J.E. Phytoplankton blooms in estuarine and coastal waters: Seasonal patterns and key species. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2015, 162, 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wang, H.; Cui, Z.; Wang, H.; Ding, X.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, H.; Li, S.; Jiang, T. Microbial community dynamics and ecological interactions during an atypical winter Cerataulina pelagica (Bacillariophyta) bloom in Laizhou Bay, southern Bohai Sea. Mar. Environ. Res. 2025, 212, 107589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuwata, A.; Takahashi, M. Life-form population responses of a marine planktonic diatom, chaetoceros-pseudocurvisetus, to oligotrophication in regionally upwelled water. Mar. Biol. 1990, 107, 503–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.; Liu, S.; Xu, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, N. Differential ecological adaptation of diverse Chaetoceros species revealed by metabarcoding analysis. Environ. DNA 2023, 5, 1332–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, P.J.; Furuya, K.; Glibert, P.M.; Xu, J.; Liu, H.B.; Yin, K.; Lee, J.H.W.; Anderson, D.M.; Gowen, R.; Al-Azri, A.R.; et al. Geographical distribution of red and green Noctiluca scintillans. Chin. J. Oceanol. Limnol. 2011, 29, 807–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, H.D.R.; Goes, J.I.; Matondkar, S.G.P.; Buskey, E.J.; Basu, S.; Parab, S.; Thoppil, P. Massive outbreaks of Noctiluca scintillans blooms in the Arabian Sea due to spread of hypoxia. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 4862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, M.; Yue, X.; Chen, Y.; Su, D.; Liu, Z. Noctiluca scintillans Bloom Reshapes Microbial Community Structure, Interaction Networks, and Metabolism Patterns in Qinhuangdao Coastal Waters, China. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Yang, Q.; Zhu, L.; Cui, Z.; Qu, K.; Wei, Y. Environmental controls on the seasonal variations of diatoms and dinoflagellates in the Qingdao coastal region, the Yellow Sea. Mar. Environ. Res. 2024, 198, 106524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishikawa, T.; Hori, Y. Effects of nitrogen, phosphorus and silicon on a growth of a diatom Coscinodiscus wailesii causing Porphyra bleaching isolated from Harima-Nada, Seto Inland Sea, Japan. Nippon Suisan Gakkaishi 2004, 70, 872–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tragin, M.; Vaulot, D. Novel diversity within marine Mamiellophyceae (Chlorophyta) unveiled by metabarcoding. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yung, C.C.M.; Redondo, E.R.; Sanchez, F.; Yau, S.; Piganeau, G. Diversity and Evolution of Mamiellophyceae: Early-Diverging Phytoplanktonic Green Algae Containing Many Cosmopolitan Species. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Wang, J.; Zuo, T.; Shan, X.; Jin, X.; Sun, J.; Yuan, W.; Pakhomov, E.A. Seasonal Changes in Zooplankton Community Structure and Distribution Pattern in the Yellow Sea, China. Front. Mar. Sci. 2020, 7, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Dong, Y.; Li, H.; Lin, S.; Huang, L.; Xiao, T.; Gregori, G.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, W. Grazing by microzooplankton and copepods on the microbial food web in spring in the southern Yellow Sea, China. Mar. Life Sci. Technol. 2020, 2, 442–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Han, M.; Dong, C.; Jia, J.; Chen, J.; Wong, C.K.; Liu, X. Mesozooplankton Selective Feeding on Phytoplankton in a Semi-Enclosed Bay as Revealed by HPLC Pigment Analysis. Water 2020, 12, 2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, Y.; Zhao, M.; Ren, H.; Zhang, D.; Yan, K.; Guo, Z.; Chen, Y. Phytoplankton Community Shifts Under Nutrient Imbalance in the Yellow River Estuary and Adjacent Coastal Waters. Water 2026, 18, 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010054

Li Y, Zhao M, Ren H, Zhang D, Yan K, Guo Z, Chen Y. Phytoplankton Community Shifts Under Nutrient Imbalance in the Yellow River Estuary and Adjacent Coastal Waters. Water. 2026; 18(1):54. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010054

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Yifei, Mingtao Zhao, Hongwei Ren, Dongrui Zhang, Ke Yan, Zhigang Guo, and Ying Chen. 2026. "Phytoplankton Community Shifts Under Nutrient Imbalance in the Yellow River Estuary and Adjacent Coastal Waters" Water 18, no. 1: 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010054

APA StyleLi, Y., Zhao, M., Ren, H., Zhang, D., Yan, K., Guo, Z., & Chen, Y. (2026). Phytoplankton Community Shifts Under Nutrient Imbalance in the Yellow River Estuary and Adjacent Coastal Waters. Water, 18(1), 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010054