3.2. Effect of Humic Acids on Spectrophotometric Analysis of Hg(II) with Dithizone

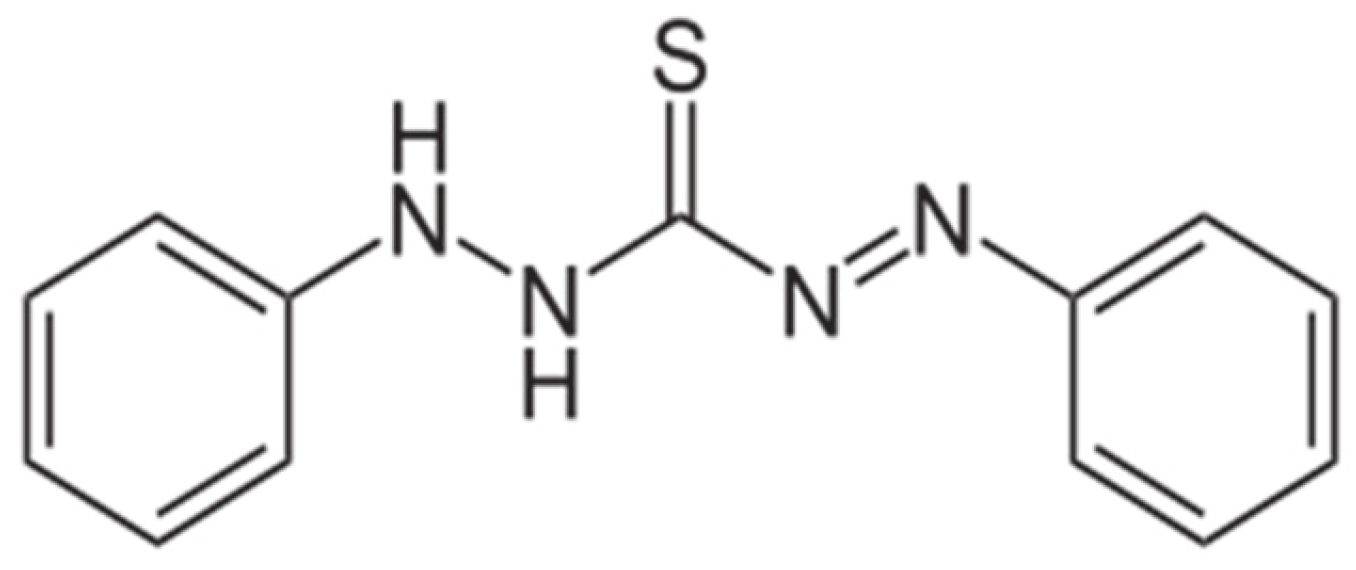

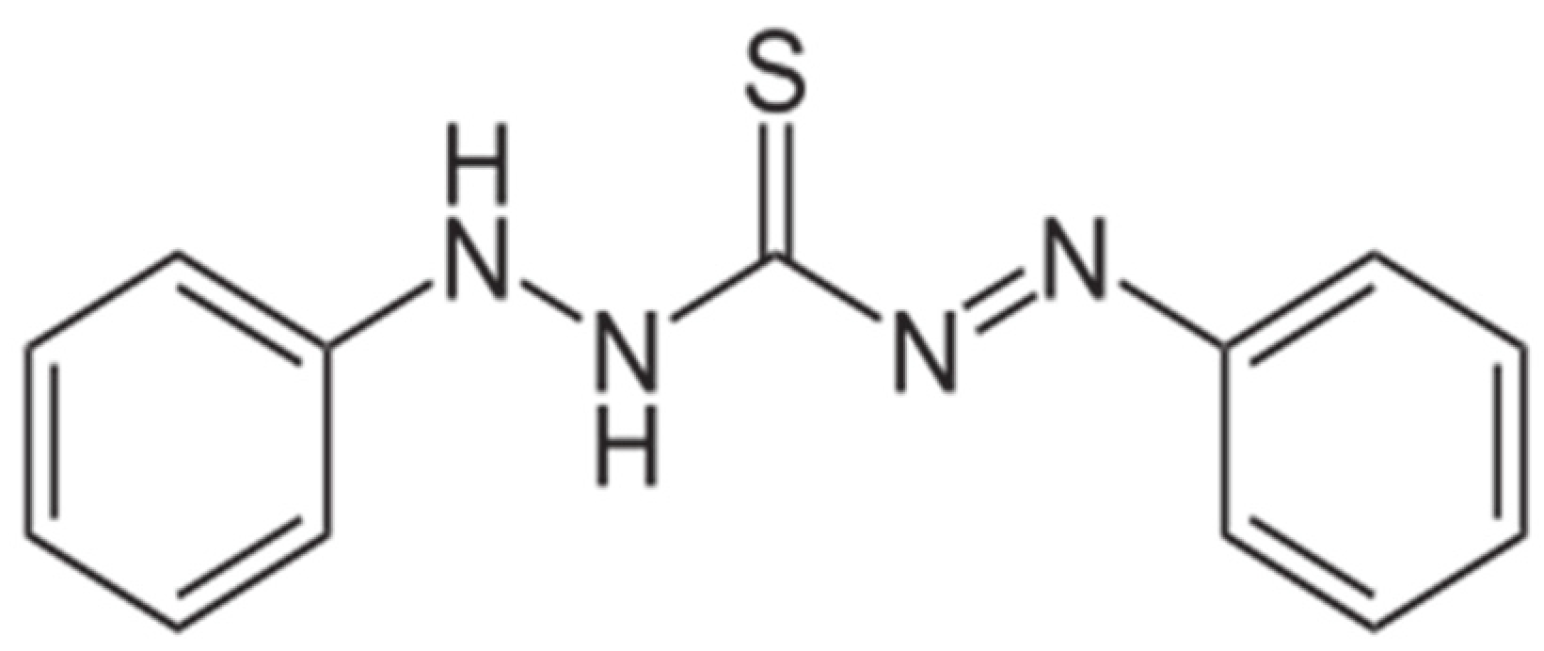

Humic acids are ubiquitous in natural waters and soils [

41,

43]. These natural products are macromolecular mixtures of polymers of poly-aromatic rings enriched with carboxylic and thiol groups [

44,

45]. Humic acids are difficult to remove from environmental samples and thus may potentially interfere with spectrophotometric analysis of Hg(II) using dithizone. To address this issue, experiments were conducted by spiking various amounts of certain humic acid in working standard Hg(II) solutions used for the calibration, and then, the slopes of the calibrations obtained in the presence and absence of the humic acid tested were compared to determine the effect of the humic acid on the Hg(II) analysis.

Two sorts of humic acids were used in this study, i.e., ADHA and ACHA (see

Section 2.1). These are commercially provided humic acids that have been widely used in research involving humic acids [

46,

47,

48,

49,

50]. To consider the potential effect of pH on the Hg(II) analysis, the experiments on the effect of humic acids were carried out first under acidic conditions (pH = 3), and then, similar tests were conducted under basic conditions (pH = 9).

Effect of humic acids. Figure 4 shows that under the acidic condition tested (pH = 3), the slopes of the Hg(II) calibrations in the presence of the humic acids decrease with increasing amounts of each humic acid tested (calibration slope vs. humic acid level) in a nearly linear fashion up to the level of 100 ppm (for ACHA, slope = −0.0006, R

2 = 0.869; for ADHA, slope = −0.0004, R

2 = 0.993,

Table 3). The calibration slopes decrease by 16.4%, 24.5%, 31.5%, and 31.1% in the presence of 25, 50, 75, and 100 ppm ACHA and by 16.8%, 19.6%, 23.4%, and 25.9% in the presence of 25, 50, 75, and 100 ppm ADHA, respectively (

Table 3,

Figure 4). Yet, the calibrations obtained in the presence of the humic acids still exhibit good linearity (R

2: 0.9872–0.9985 for ACHA and 0.9973–0.9988 for ADHA) (

Table 3 and

Table 4). The effect of the humic acids on the Hg(II) analysis at pH 3 was further confirmed by an elaborated experiment using ADHA at more levels (pH 3) (

Table 4).

Although the calibration slope decreases are significant in the presence of the humic acids tested, our results indicate that the presence of the humic acids at levels up to 100 ppm does not appear to cause an interference with the Hg(II) analysis but indeed decreases the sensitivity of the Hg(II) analysis. It is also interesting to note that the two humic acids used in this study (ADHA and ACHA) appear to exhibit a similar effect at the pH tested (pH = 3), as evidenced by the close overlap of the two calibration slope curves for the two humic acids (

Figure 4).

Typical concentrations of dissolved organic matter in natural waters are in the range of 1–100 mg C L

−1 (ppm carbon, or ppm C) [

51]. Assuming the carbon contents of organic matter (humic matter) are commonly about 50–60% [

52], the humic acid level of 100 ppm (mg L

−1) in this study is equivalent to 50–60 ppm C, well within the common levels of aquatic dissolved organic matter. The present study thus shows that the linearity of the spectrophotometric analysis of Hg(II) with dithizone can hold valid for water samples containing up to about 50–60 ppm C. Above these levels, caution needs to be exercised to inspect the validation of the linearity of the Hg(II) analysis calibration.

The same experiments on the effect of the humic acids were also carried out at pH 9 using ADHA to investigate and illustrate the manifestation of the humic acid effect under basic conditions. Similar decreases in the calibration slopes in the presence of ADHA are evident (

Table 5,

Figure 5). The effect of ADHA on the Hg(II) analysis at pH 9 was further confirmed by elaborated experiments using ADHA at more levels (pH = 8, 9) (

Figure 6) and at pH 6–9 with various ADHA levels (

Table 6). An elaborated discussion on the effect of pH on the Hg(II) analysis in the presence of humic acids is detailed in a subsequent section.

Effect of carboxylic group and thiol group of model ligands (oxalate and cystine). Humic acids contain two major functional groups that can interact with Hg(II), i.e., a carboxylic group (–COO

− from –COOH) and a thiol group (–S

− from –SH). These can compete with dithizone for Hg(II) to form stable Hg(II) coordination compounds (

Figure 2) and thus affect the Hg(II) analysis. To investigate the role of these two functional groups in the effect of humic acids on the Hg(II) analysis, we spiked oxalate (model organic acid ligand with carboxylic groups) and cysteine (model organic acid ligand with both carboxylic and thiol groups) in the working standard Hg(II) solutions to compare the slopes of the calibrations in the presence and absence of these model agents to act as the ligands for Hg(II).

Figure 4 shows that under the acidic condition (pH = 3), oxalate only has a slight effect, but cysteine exhibits a substantial effect. The decreases in the calibration slopes for oxalate range from 12% to 14% at the concentrations of 25–100 ppm (136–543 μM), while those for cysteine have a larger range of 14% to 35% at the very low concentrations (≤3 ppm or 12.4 μM) (

Table 3). The effect of cysteine on the Hg(II) analysis was confirmed by an elaborated experiment at more cysteine levels (pH = 3) (

Figure 7).

Similarly, under the basic condition (pH = 9), oxalate also has the slightest effect, with the percentage decreases in the calibration slopes being 0.8%, 2.3%, 9.8%, and 25.9% at the oxalate levels of 7.5–60 ppm (40.7–325.8 μM), respectively (

Table 5,

Figure 5). On the contrary, cysteine exhibits the strongest effect with the percentage calibration slope decreases of 24.8%, 34.9%, and 54.9% at the cysteine levels of 0.125–0.500 ppm (1.03–4.13 μM), respectively (

Table 5). As a comparison, under the basic condition (pH = 9), the calibration slopes decrease by 5%, 9%, and 64.7% in the presence of 2.7, 4.0, and 10.0 ppm ADHA, respectively (

Table 5).

Likewise, as seen for the effect of the humic acids at pH 3, all the calibrations under the basic conditions also show good linearity (R

2: 0.9850–0.9997 for ADHA, 0.9897–0.9987 for oxalate, and 0.9980–0.9985 for cysteine,

Table 5 and

Table 6,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). These results indicate that the analytical method of spectrophotometric analysis of Hg(II) with dithizone retains fine calibration linearity in the presence of the humic acids and ligands tested under both acidic and basic conditions, without an alternation of its validation and effectiveness.

The results of our study on the effect of humic acids on the Hg(II) analysis as compared to the effect of the model ligands (oxalate and cysteine) suggest that thiol groups are mainly or more responsible for the effect of the humic acids on the Hg(II) analysis observed. This is consistent with the known notion that a thiol group (soft ligand) has a very high affinity for Hg species (soft metal ion) [

53,

54,

55,

56,

57].

It needs to be pointed out that cysteine not only exhibits a pronounced effect but also does so at very low or much lower concentrations (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5, and

Figure 7;

Table 3 and

Table 5). This indicates that cysteine can cause the effect much more efficiently as well as more intensively. Interestingly, although cysteine strongly affects the Hg(II) analysis, it is also noteworthy that this effect becomes significant only at a cysteine concentration above ~0.5 ppm (~4.1 μM) at pH 3 (

Figure 4) and ~0.25 ppm (~2.05 µM) at pH 9 (

Figure 5 and

Figure 7).

It is notable that although both oxalate and cysteine can affect the sensitivity of the Hg(II) analysis to various degrees, the calibration curves still clearly retain good linearity in the presence of these agents (

Table 3 and

Table 5). This is consistent with the observation for the effect of the humic acids (

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6;

Table 3,

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6). Incidentally, the calibration slopes decrease in the presence of cysteine in a linear fashion (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4), which is also consistent with the observation for the effect of the humic acids. These results reinforce the notion that the thiol groups in humic acids play a leading role in affecting the sensitivity of the Hg(II) analysis.

An empirical functional-group model for effect of humic acids on the Hg(II) analysis. To further investigate the role of the two functional groups in their effect on the sensitivity of the Hg(II) analysis, an attempt was made to model the effect of humic acids on the sensitivity of the Hg(II) analysis. This model originates from the findings described below.

As seen in

Figure 4, the curves of the calibration slope vs. the humic acid level in the case of the two humic acids tested (ADHA and ACHA) under the acidic condition (pH 3) are located somewhat below the curve for oxalate and quite far above the curve for cysteine. On the other hand, the curve of the calibration slope vs. the humic acid level for ADHA under the basic conditions (pH 9) is located quite below the curve for oxalate and closely above the curve for cysteine (

Figure 5). These observations share a common feature, i.e., the curve(s) of the calibration slope vs. the humic acid level is located in between the curves for oxalate and cysteine under both acidic and basic conditions.

The above findings prompted us to formulate a functional-group model to account for the effect of humic acids on the Hg(II) analysis. We created an index to measure the effect of various agents on the sensitivity of the Hg(II) analysis. This index is given by the slope of the curve (line or plot) of the calibration slope vs. the level of the agent present (tested) as shown in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5. This value is called the index for the sensitivity evaluation for the Hg(II) analysis—in short, the Sensitivity Evaluation Index (SEI).

The SEI values at pH 3 can be found to be −4 × 10

−4 for ADHA (SEI

ADHA), −6 × 10

−4 for ACHA (SEI

ACHA), −7 × 10

−5 for oxalate (SEI

ox), and −4.06 × 10

−2 for cysteine (SEI

cyst) (note: the negative sign is due to the nature of a decrease in the calibration slope with increasing concentration of the affecting agent present) (

Table 3).

With the SEI values obtained, we can formulate an empirical model to describe and measure the effect of the carboxylic and thiol groups of the humic acids on the sensitivity of the Hg(II) analysis as follows:

where

n and

m are adjustable coefficients (model parameters), and the values of SEI

HA for ADHA and ACHA, SEI

ox, and SEI

cyst for the acidic conditions (pH 3) can be obtained from

Table 3. Hence, we have the following:

The values of

n and

m can be assigned to give various scenarios of the model. A particular set of the

n and

m values as approximation can be obtained from the fractions of the carboxylic and thiol groups in humic acids and then adopted in the above model (Equation (2)). The fraction of the carboxylic groups in humic acids varies, but a common, representative value that may be selected for use is 0.21 (

n = 0.21 for 4.6 meq. −COOH/g HA or 0.21 g −COOH/g HA as equivalent with M

–COOH = 45 g mol

−1) [

43,

58]. The fraction of the thiol groups in humic acids that may be selected for use is 0.00176 (

m = 0.00176; considering the fraction of the total S in humic acids as 0.004 and the fraction of the thiol in the total S as 0.44, 0.004 × 0.44 = 0.00176) [

43,

59].

Applying the fractions for −COOH (

n = 0.21) and for −SH (

m = 0.00176) in the above model equation (Equation (2)) yields a value for SEI

HA shown below:

The above value is quite close to or at least on the same magnitude of the actual SEI

HA values for the ADHA and ACHA obtained experimentally (−4 × 10

−4 for ADHA and −6 × 10

−4 for ACHA,

Table 3). Hence, this empirical model appears to work fairly well in accounting for the effect of the –COOH and –SH groups of humic acids on the sensitivity of the Hg(II) analysis.

Interestingly, the same treatment for the case under the basic conditions (pH = 9) (SEI

ox = −3 × 10

−3 and SEI

cyst = −5.3 × 10

−2,

Table 5;

n = 0.21 and

m = 0.00176) would lead to a value of the SEI

ADHA being −7.2 × 10

−4, which is two orders of magnitude lower than the experimentally obtained value (−5.8 × 10

−2,

Table 5).

The above model-predicted SEI

ADHA value for pH 9 indicates that the empirical model fails in the case for the basic conditions. This is probably because at pH 9, the sensitivity of the Hg(II) analysis is affected by both humic acids (mainly thiol groups) and pH (−OH ligand as a competing agent other than thiol group for Hg(II)). Hence, the SEI

ADHA reflects combined effects of both thiol and hydroxyl groups on the sensitivity of the Hg(II) analysis, while the model considers only the effects of carboxylic and thiol groups. In other words, the model may be modified to include the effect of the −OH ligand as follows:

where

p is an adjustable coefficient (model parameter) similar to

n and

m in Equation (1). Various scenarios of the model parameters of

n,

m, and

p may be entertained as desired to look into how the effect of humic acids on the Hg(II) analysis manifests through these functional groups or agents.

The absolute values of the SEI indexes can be considered a measure of the degree of the effect of humic acids on the sensitivity of the spectrophotometric analysis of Hg(II) with dithizone. Higher absolute values of the SEI indicate a higher humic acid effect. This index (calibration slope per ppm humic acid) is also useful in estimating the humic acid effect at various levels of humic acids present in water samples.

Analytical implication of the effect of humic acids on the Hg(II) analysis. Since the calibration remains essentially valid (linear) in the presence of the humic acids or other effective agents (

Table 3,

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6), and moreover, the sensitivity effect is also fairly linear (

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7), the curves of the decrease in the calibration slope vs. the concentration of the humic acid (or an affecting agent) can provide an analytical tool to measure and calibrate the sensitivity effect of humic acids or other agents on the Hg(II) analysis. We can find the specific relevant calibration slope for analyzing Hg(II) in the presence of a given level of the humic acid (or an affecting ligand) from the linear plot of the calibration slope in the presence of the humic acid (or the affecting ligand) vs. the concentration of the humic acid (or affecting ligand) as shown in

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 and

Table 3,

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6.

3.3. Effect of Ligands on Spectrophotometric Analysis of Hg(II) with Dithizone

Hg(II) is hardly found as a free Hg

2+ cation in natural aquatic systems or in aqueous solutions, but it actually is present as a coordination compound with various ligands. Even in pure water, Hg(II) exists as an aquo complex (coordination compound) with water molecules as the ligands to form a hydration shell around each Hg(II). Other ligands that typically form coordination compounds with Hg(II) include both inorganic (e.g., Cl

−) and organic species (e.g., oxalate, citrate, and cysteine). As discussed previously, these ligands can compete with dithizone to bind with Hg(II) (

Figure 2) and thus may interfere with spectrophotometric analysis of Hg(II) with dithizone.

Our study on the effect of the humic acids on the spectrophotometric analysis of Hg(II) as presented in

Section 3.2 shows that aquatic ligands can indeed affect the Hg(II) analysis through ligand competition for Hg(II) (

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7,

Table 3,

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6). To further verify and investigate the role of the ligands with respect to the applicability of the dithizone method for Hg(II) analysis, we conducted an extensive study on the effect of ligands for the Hg(II) analysis. In this study, the regular aquo-Hg(II) standards were substituted with Hg(II)–ligand standards (Hg(II)L). It should be pointed out that Hg(II)L is a general notion of expressing the Hg(II)L complexes (coordination compounds) and thus does not reflect that actually there is always a 1:1 ratio of mercury–ligand. As a matter of fact, dithizone is a bi-dentate ligand with −S and −N as the lone electron pair donor atoms, and the Hg(II)–dithizone coordination compound exists as Hg(II)-dithizone

2 (

Figure 2).

Specifically, we used various Hg(II)L (L = chloride, cysteine, citrate, and oxalate) stock solutions to prepare and use as the Hg(II) standard solutions for the Hg(II) calibration. The slopes of the calibrations were obtained and compared with the slopes in the absence of any added ligand (i.e., in water only with Hg(II) predominantly as Hg(OH)2 at both pH 4.2 and 7.2).

It is important to note that for the present study and in Hg(II) samples of environmental waters, Hg(II) is never really found in the absence of any ligand, as previously discussed. Thus, an absence of any added ligand actually means that Hg(II) exists as Hg(OH)

2 regardless of the pH (4.2 or 7.2 used for the present study), as indicated by the species distribution diagrams for every experimental test scenario obtained by the computer speciation modeling program (Visual MINTEQ, Version 3.1, 2014) [

31]. In consideration of the potential effect of pH on the Hg(II)L analysis, the experimental tests for this ligand effect study were carried out first under acidic conditions (pH = 4.2) and then similarly under circumneutral conditions (pH = 7.2). These two selected pH conditions offer additional pH conditions (in addition to the two pH conditions of pH 3 and pH 9 used in the study on the effect of humic acids) to enlarge the specific pH scenarios covered for the study of the effect of ligands.

Table 7 provides the percentage decreases in the Hg(II) calibration slopes with the calibration linearity (R

2) for spectrophotometric analysis of Hg(II) using dithizone in the presence of chloride, cysteine, citrate, or oxalate at the levels tested and pH 4.2 as compared to the regular calibration in the absence of the ligands (water only with hydroxyl as the ligand for the regular calibration). The results show that under acidic conditions (pH = 4.2) at the ligand levels tested, citrate has only a slight effect, chloride and cysteine have a similar effect that is slightly greater than the effect of citrate, and oxalate exhibits the largest ligand effect on the Hg(II) analysis.

The decrease in the Hg(II) calibration slopes (i.e., a decrease in the sensitivity of the method) in the presence of the ligands ranges from 3.3% for citrate at the level of 1.0 × 10−3 M (1.0 mM) to 14.1% for oxalate at the same level. Chloride and cysteine exhibit a similar slope decrease at around 9% but at much lower concentrations tested than citrate or oxalate (Cl−: 2.0 × 10−5 M; cysteine: 4.1 × 10−6 M).

It is notable that oxalate exhibits a larger effect than cysteine because oxalate has a much higher concentration (1.0 × 10

−3 M for oxalate vs. 4.1 × 10

−6 M for cysteine). This shows that even though carboxylate group is a weaker ligand with a lower affinity for Hg(II) (a soft Lewis acid or soft metal ion, logK

f-Hg(II)–oxalate = 9.7) than a thiol group (logK

f-Hg(II)–cysteine = 14.4) (

Table 2), oxalate can still affect the Hg(II) analysis more pronouncedly than cysteine at significantly higher levels. This indicates that the effect of the ligands depends not only on the ligand sort but also on the ligand level. This implicates that carboxylate groups in humic acids can still play a significant role depending on the ligand quantity, although their affinity for Hg(II) is weaker than the thiol group-containing ligands.

The basic condition (pH 7.2) sees similar results with the exception of cysteine, exhibiting a much stronger effect than at pH 4.2 at the same concentration. Citrate has the lowest percentage slope decrease again (3.5%), followed by chloride at 7% and oxalate at 10.4%, with cysteine causing the largest percentage slope decrease at 31.3% (

Table 8).

It needs to be pointed out that regardless of the slope decreases, all of the calibrations under both pH conditions show satisfactory linearity (R2: 0.9987–0.9999 for chloride, 0.9919–9981 for cysteine, 0.9999 for citrate, and 0.9973–0.9975 for oxalate). This confirms the same finding presented previously for the effect of humic acids: the ligands as well as humic acids only affect the sensitivity of the Hg(II) analysis method and not the linearity of the calibration for the method.

The special effect of cysteine is reflected by the fact that although its level (μM) is one order of magnitude lower than Cl− (101 μM) and three orders of magnitude lower than citrate and oxalate (mM), its effect stands out nearly the same at pH 4.2 or even much stronger at pH 7.2 as compared with the other ligands. This is a manifestation of the stability of the Hg(II) coordination compounds since the formation constant (Kf) for Hg(II) with cysteine is several orders of magnitude higher (1014.4) as compared with the Kf with citrate (1010.9) and oxalate (109.7). Interestingly, citrate and oxalate have varying effects on the Hg(II) analysis, which is rather unexpected since both ligands contain carboxylic groups and have similar stability constants.

Another interesting finding is the pH dependence of the ligand effects. The effect of citrate appears nearly the same at both pH conditions (similar slope decreases,

Table 7 and

Table 8), while oxalate has a higher effect at pH 4.2 (more slope decrease). It needs to be pointed out that while the actual slope of oxalate at pH 4.2 appears higher (m = 0.0443) than the slope at pH 7.2 (m = 0.438), the slope decrease (%) is based on its comparison with the baseline calibration slope, which is the slope of only Hg(II) with no added ligand (i.e., Hg(II)–hydroxide complex) at the appropriate pH (see footnote on

Table 7 and

Table 8).

3.4. Effect of pH on Spectrophotometric Analysis of Hg(II) with Dithizone

Spectrophotometric analysis of Hg(II) using dithizone is commonly carried out under acidic conditions [

38,

39]. This practice is adopted to ensure that all Hg(II) remains completely dissolved as Hg

2+ species. Under acidic conditions, Hg(II) speciation favors the free ion (Hg

2+) when no ligand for Hg(II) is present or added, and Hg(II) is fully ionized in the aqueous solution and can readily bind with dithizone.

Operationally, Hg(II) samples are commonly acidified first before being analyzed. Yet, acidic conditions deviate from the environmentally realistic settings commonly seen. There are occasions in which Hg(II) samples need to be analyzed under original conditions. We conducted experiments to test the applicability of the spectrophotometric analysis of Hg(II) under basic conditions as compared with the acidic condition. This was achieved by running the Hg(II) calibrations using standard Hg(II) solutions at pH 3 and pH 6–9 for the study on the effect of humic acids. The test on the effect of pH was accomplished for the study on the effect of ligands by running the Hg(II) calibrations under slightly acidic conditions (pH 4.2) and circumneutral (near neutral) conditions (pH 7.2). These pH values were chosen to mimic different environmental systems, where pH 7.2 is typical of many freshwater aquatic systems, while pH 4.2 is typical of freshwater systems subjected to acid mine drainage.

Effect of pH in association with the effect of humic acids. Our study shows that in the absence of humic acids, the calibration slopes become smaller at pH 6–9 (average slope = 0.6922,

Table 5) as compared to those at pH 3 (average slope = 0.7898,

Table 3 and

Table 4), which amounts to a ~12% decrease. Nevertheless, the calibrations still exhibit good linearity at pH 6–9 (R

2 = 0.9813–0.9989 without ADHA,

Table 5). This indicates that at neutral or basic pH, the spectrophotometric analysis of Hg(II) using dithizone is still effective but with lower sensitivity. This is similar to what was observed in the presence of the humic acids. However, our results show that at pH ≥ 10, no Hg(II) is detectable, indicating the failure of dithizone to bind Hg(II) under the high pH conditions in competing for Hg(II) with the −OH

− group.

It is well known that at neutral and basic pH, HgOH

+ and Hg(OH)

2 are the two dominant Hg(II) species [

60]. Under the high pH conditions, dithizone becomes weaker in competing with −OH

− ligand to form coordination compounds with Hg(II). Hence, less Hg(II) can bind to dithizone, and eventually, all Hg(II) forms Hg(OH)

2 at the high pH, which leads to the decrease in the calibration slopes and ultimate failure of the method at pH ≥ 10.

It is interesting to note that our study shows that at pH 6–9, in the absence of humic acids, the calibration slopes differ moderately, exhibiting only slight decreases in the calibration slopes with increasing pH (

Figure 5,

Table 5). This is most likely because at this pH range, Hg(II) is already present mainly as Hg(OH)

2. In summary, the spectrophotometric analysis of Hg(II) using dithizone is still effective, with good linearity but lower sensitivity at high pH up to pH = 9. However, the method fails to function at pH ≥ 10.

In the presence of humic acids and at high pH simultaneously, the calibration slopes decrease to larger degrees as compared to in the absence of humic acids. This is indicative of a two-fold effect (both humic acid and pH) jointly affecting the Hg(II) analysis. It is well known that at high pH, more thiol groups become deprotonated, and thus, more thiol groups become available to effectively bind Hg(II). Hence, high pH enhances the effect of humic acids, leading to even lower calibration slopes (sensitivity) (

Table 5).

Effect of pH in association with the effect of ligands. Table 9 provides a collective summary of the results of the study on the pH effect. This summary offers an overview of the pH effect for a general inspection. Here, it is worth mentioning that the slope is 0.0516 at pH 4.2 and 0.0489 at pH 7.2 in the absence of any other ligand, such as citrate, oxalate, cysteine, or chloride. It is understandable that at high pH, more Hg(II) binds to −OH

− groups, making Hg(II) less accessible or amenable to forming a complex with dithizone.

In the presence of various ligands and at high pH simultaneously, it is notable that the effect of cystine is much higher at pH 7.2 (31.3% slope drop) than at pH 4.2 (9.3% slope drop) (

Table 7 and

Table 8). This may be related to the speciation variation of cysteine with pH. At pH 7.2, the thiol group of cysteine tends to be deprotonated, releasing the donor sulfur atom and causing the ligand to readily make a coordination bond with Hg(II) (i.e., donating a lone pair of electrons from S to Hg(II)). At pH 4.2, some of the thiol groups remain protonated and thus unavailable to form the bond with Hg(II).

A similar pH effect concerning the influence of chloride on the Hg(II) analysis is observable. The effect of chloride is higher at pH 4.2 than at pH 7.2. At pH 4.2, fewer –OH− groups are present in the inner coordination sphere of the Hg(II)–hydroxyl coordination compound, which leaves more room for Hg(II) to bond to Cl−, while at pH 7.2, the opposite is seen.

Finally,

Table 10 provides an overview of the effect of the ligands of oxalate and cysteine on the spectrophotometric analysis of Hg(II) at various pH (pH = 3–9). This table clearly shows how the calibration slope decreases with increasing pH, resulting in a pH-dependent sensitivity variation for a particular ligand of concern.

3.5. Improvement and Refinement of Analytical Procedures and Operations

In spite of the wide use of the method of spectrophotometric determination of Hg(II) using dithizone in the environmental field, there is a lack of a comprehensive documentation of the operational procedures with sufficient technical details provided to serve as a useful reference. Many seemingly trivial technical details are often omitted in the literature. At times, there is a need for further improvement or modification when this method is applied to various cases in environmental analysis and research. Here, we report several improvements or refinements developed when this method was applied to our environmental research [

40], with the intention that these details may be beneficial for various applications. An updated comprehensive documentation of the method for spectrophotometric analysis of Hg(II) using dithizone with sufficient technical details of the operational procedures and the new improvements and refinements from this study is provided in

Appendix A.

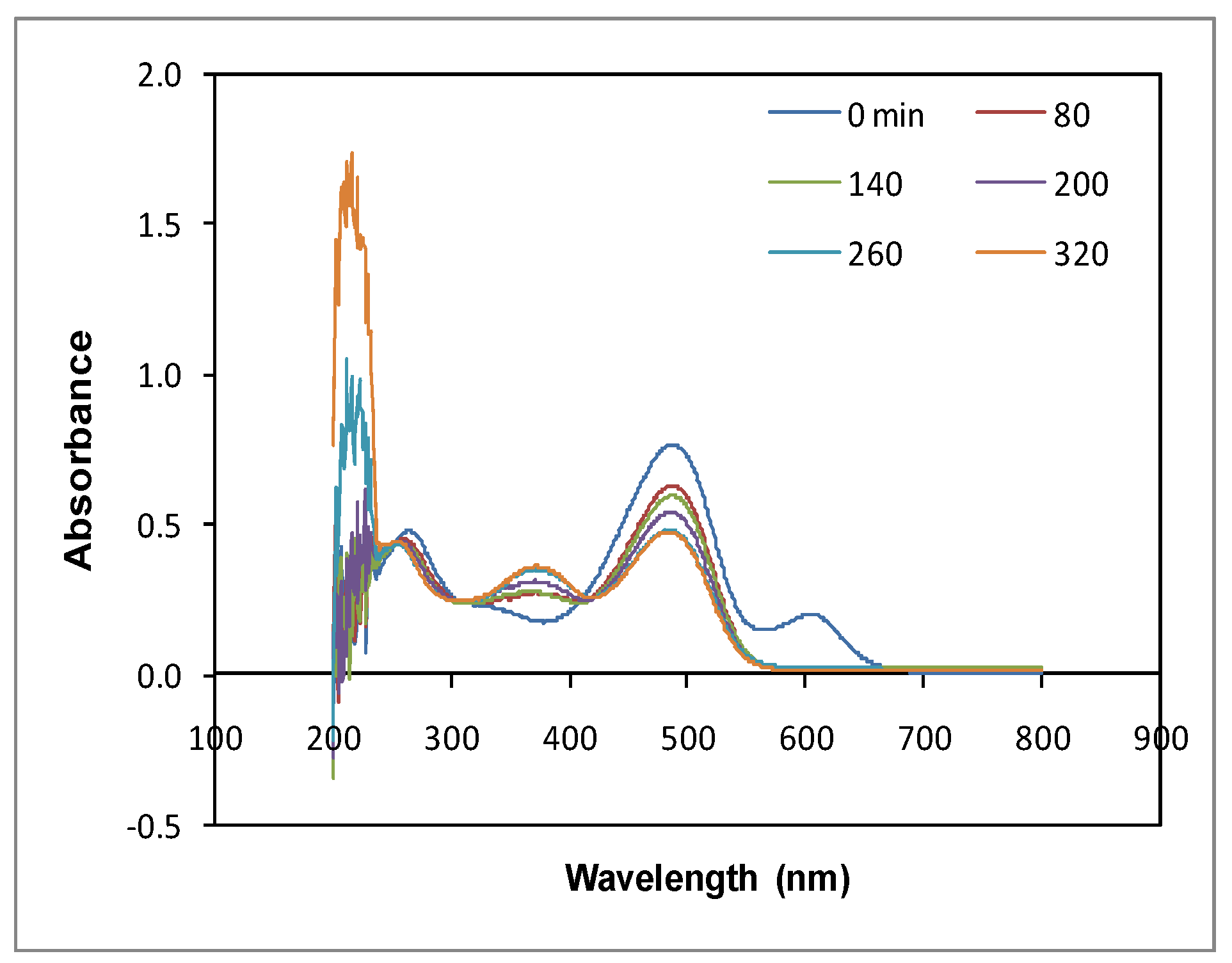

Decomposition and concentration of dithizone. Spectrophotometric analysis of Hg(II) using dithizone requires formation of Hg(II)–dithizone coordination compound. However, dithizone is prone to gradual decomposition at room temperature even in the dark [

61].

Figure 8 shows 3 × 10

−5 M (30 μM) of dithizone in a chloroform solution decomposed continuously within 285 min. With decomposing of dithizone ligand, the Hg(II)–dithizone coordination compound molecules consequently underwent a gradual loss (

Figure 9). This disadvantage is commonly overcome by using an excessive amount of dithizone to ensure that all the Hg(II) is always kept complexed with dithizone. A certain amount (or concentration) of dithizone is recommended or reported for use in the literature (e.g., ~0.0039 g dithizone in 500 mL chloroform) [

30,

39].

However, it needs to be pointed out that one particular concentration is not universally applicable to all cases of its use. Actually, the degree of the excess of dithizone required depends on and should be varied or adjusted according to the level of Hg(II) present to be analyzed. Generally, Hg(II)–dithizonate is orange in color, while the dithizone ligand itself is dark green. Hence, a deep-greenish or purple-greenish color should register the presence of excessive dithizone since both dithizone ligand and the Hg(II) coordination compound are present, while an orange color signals the deficiency of dithizone present. In our study, the amount of dithizone was increased to ~0.02 g in 100 mL of chloroform, and 5 mL of this concentrate was diluted in 50 mL of chloroform and used for the Hg(II) extraction for the Hg(II) levels of 0.6–1.2 mg L−1 (ppm) (3–6 µM).

In summary, because of the decomposition of dithizone, to ensure the presence of a sufficient (excessive) amount of dithizone to complex with the Hg(II) completely at the levels of Hg(II) encountered, there is a need to adjust the concentration of dithizone to ensure that over a certain period of time during the Hg(II) analysis accompanying the decomposition, dithizone still remains sufficiently excessive as required. In practice, this can be gauged by watching the color (its change) of the dithizone solution over time as discussed above.

Analytical blank for spectrophotometric analysis of Hg(II). Spectrophotometric analysis generally requires use of an analytical blank to zero the spectrophotometer to deduct the light absorption caused by the substances other than the analyte. For the Hg(II) analysis using dithizone, chloroform is commonly or conventionally used as the blank. However, dithizone itself also absorbs light at the wavelength used for the Hg(II) analysis (

Figure 8). This is reflected by the intercept of the calibration equation in proportion to the concentration of dithizone in the solution analyzed. Yet, dithizone decomposes over the course of the analysis. Consequently, the absorbance blank from dithizone (i.e., the calibration intercept) decreases over time. This can result in certain analytical errors when the same calibration equation is used over time, with the intercept only corresponding to the initial level of dithizone. Similar errors can occur when different levels of dithizone are used in the Hg(II) extraction.

To eliminate the analytical error caused by dithizone decomposition as discussed above, we employed the dithizone in chloroform solution specifically used for Hg(II) extraction during the Hg(II) analysis as the analytical blank instead of simply chloroform to zero the spectrophotometer. By this practice, the blank from dithizone can be removed regardless of the actual level of dithizone present in the solution being analyzed or the changing of dithizone level caused by its decomposition. Operationally, a portion of the working dithizone solution used for Hg(II) extraction is saved and then used to zero the spectrophotometer each time when a calibration is conducted, or a Hg(II) sample is analyzed.

Sensitivity improvement. A useful means to increase the sensitivity of spectrophotometric analysis is an employment of a longer light path (

b) according to Beer–Lambert’s law (

A =

εbc). To analyze Hg(II) at lower concentrations, we used a set of triplet 1 cm cuvettes in a row instead of a singlet 1 cm cuvette. Operationally, one additional cuvette with the solution analyzed is placed immediately by each side of the original singlet cuvette along the light path. The spectrophotometer usually has sufficient space to accommodate two additional 1 cm cuvettes. The average calibration curve slope obtained using three cuvettes is 0.861 as compared to the slope of 0.297 with a single cuvette. The measured ratio of the two slopes was 2.9:1, very close to the theoretic value of 3:1. Hence the sensitivity can be increased in such a simple way as described above. The detection limit of this method with a singlet cuvette should be one-third of that with a set of triplet cuvettes.

Figure 10 shows how the arrangement of the cuvettes in the spectrophotometer can be accomplished.

3.6. Evaluation of Spectrophotometric Analysis of Hg(II) with Dithizone

An analytical method is generally evaluated based on the following analytical factors: (1) accuracy and precision, (2) reproducibility, (3) selectivity, (4) linearity and linear range of the analytical calibration, (5) sensitivity, and (6) interference. Our study shows that humic acids and ligands are influential in spectrophotometric Hg(II) analysis using dithizone mainly with respect to analytical sensitivity and interference, with the rest of the factors (factors (1)–(4)) remaining intact.

The sensitivity of an analytical method is reflected and quantified by the slope of the calibration. The greater the slope value, the higher the sensitivity of the method. Our study shows that the effect of the humic acids and ligands materializes mainly in terms of the sensitivity change (specifically sensitivity decrease as a result of the presence of the humic acids or ligands). Even the effect of pH still registers a manifestation of the effect of the ligands (–OH− ligand). Hence, the apparent interference in the method by humic acids and ligands actually does not invalidate the method.

Figure 11 provides a compilation of all absorbance readings taken during the study on the effect of the ligands. This shows that while each condition may affect the calibration slope to some extent, the standard deviations appear to be small. Yet, it needs to be pointed out that this standard deviation is for absorbance, but when converted to concentration (µM), the significance (meaning) of the standard deviation becomes clear. Therefore, using the proper calibration curve with the effect of humic acids or ligands considered for the dithizone method is crucial to limiting analytical errors.

This research shows that the dithizone method can still be used effectively even in the presence of humic acids or ligands, but the specific calibration needs to be performed in the presence of the ligand(s) and at the ligand level(s) and pH relevant to the study conditions (instead of just universally acidifying the Hg(II) solution/sample to ensure Hg(II) being fully soluble).

Yet, although the spectrophotometric analysis of Hg(II) using dithizone remains be a valid, reliable analytical method, overlooking the interference of humic acids and ligands in terms of decreasing the analytical sensitivity and a lack of appropriate measures to address the interference can surely result in considerable or significant analytical errors and experimental artifacts. It is recommended that appropriate analytical calibrations be conducted with the effect of humic acids and ligands in consideration and, furthermore, only the specific calibration in the presence of the humic acid or ligand of concern at the relevant level(s) at the relevant pH be employed appropriately to calculate the results of the analytical unknowns. Such a caution with the appropriate operating measures can never be overstated.