1. Introduction

From a global perspective, the frequency, persistence, and severity of harmful algal blooms (HABs) have increased, jeopardizing ecosystem sustainability and posing numerous risks to human health [

1]. In particular, blooms formed by toxic algae (toxic HABs) are considered ecological catastrophes that threaten both inland and coastal ecosystems [

2].

Prymnesium parvum blooms, which were once common in inshore localities [

3], are currently categorized as “ecosystem-disruptive algal blooms” [

4].

Belonging to Haptophyta,

Prymnesium parvum N. Carter, 1937, often called “golden alga” because of the golden-brown color of its photosynthetic pigments, it is a tiny, ellipsoid microorganism (∼10 μm in diameter) tolerant of a broad range of temperatures and salinities [

5]. It is already widespread across five continents in brackish and high-mineral-content waters [

6]. This species produces a set of highly potent toxins, prymnesins, which exert ichthyotoxic, cytotoxic, and hemolytic effects on gill-breathing aquatic animals such as fish, mollusks, and amphibian tadpoles [

7] and also have a broad spectrum of biological impacts [

8]. Prymnesins represent large ladder-frame polyether compounds, which are divided into three types that differ in the number of carbon atoms in the agylcon backbone structure (A-type: 91; B-type: 85; and C-type: 83). Different types seem to have different toxicities, and each strain of

P. parvum produces only one type of prymnesin, though they may represent different variants [

9].

Additionally,

P. parvum can defend itself from grazing organisms [

10], compete for nutrients through autotrophy, mixotrophy, and saprophytic nourishment [

11], and inhibit the development of other phytoplankton species through allelopathy [

12]. These eco-physiological features indicate that

P. parvum blooms disrupt the functioning of planktonic food webs [

13]. While risks to human health have not yet been reported based on environmental data, the latest laboratory experiments indicate that prymnesins are toxic to human lung cancer cells and healthy skin cells and have significant effects on human neuronal cell lines, suggesting the presence of neurotoxicants [

14,

15].

Given the issues this species can cause, it is crucial to explore and improve methods for controlling its blooms [

16]. Managing toxic HABs can be approached in several ways, with prevention methods regarded as the safest and most environmentally friendly option [

17]. However, preventing blooms by reducing nutrient inputs is a long-term process; therefore, in the short to mid-term, it is often necessary to manage existing blooms or prevent them from entering new ecosystems. In the case of

P. parvum, hydrogen peroxide (HP) has been used as a treatment method in aquaculture [

18] and tested in the natural environment of the Norfolk Broads [

19], where it led to a significant decrease in

P. parvum abundance, measured by ITS copy numbers, within several hours. However, the effects of HP on other phytoplanktonic algae or prymnesin concentrations were not examined in these studies.

The Odra (Oder) River is one of the largest rivers in Central Europe, stretching 854 km and serving as a border river for 180 km between Poland and Germany. In 2022, Poland and Germany experienced a prolonged and large-scale mass fish kill along the Odra. From the end of July to the beginning of September 2022, significant levels of irregular morbidity and mortality were detected in various fish species. These massive fish deaths resulted in a 60% decrease in the fish population compared to before the disaster [

20]. In addition to common fish species such as ruffe, bream, perch, asp, pike, zander, and catfish, there was also high mortality among fish protected by Polish and European law (the EU Habitats Directive), including sturgeon (

Acipenser oxyrinchus), amur bitterling (

Rhodeus sericeus), and spined loach (

Cobitis taenia). The estimated total fish mortality was approximately 3.3 million fish, amounting to 1650 tons [

20], with the losses described being much more significant than initially expected [

21]. Alongside fish, other gill-breathing organisms, such as mussels and snails, suffered in the disaster, leading to an 88% decline in mussels of the Unionidae family and an 85% population decrease in

Viviparus viviparus [

20]. The 2022 Odra River event ranks among the largest ecological disasters caused by

P. parvum blooms worldwide [

6,

21].

Unfortunately,

P. parvum repeatedly occurs in tributaries of the Odra River, primarily in the Gliwice Canal, where it can reach high abundances. This poses a risk that the haptophyte could re-enter the river, leading to another immense bloom and associated massive fish kills. Therefore, this study aimed to test the HP method in the laboratory to assess the influence of various HP concentrations on

P. parvum, other phytoplankton taxa, and the presence and concentrations of prymnesins. Until recently, no standards for prymnesins were available; as a result, it was possible to detect their presence in water and, using indirect methods of quantification, assess the molar sum of prymnesins in water samples and in algal biomass [

9]. In this experiment, we not only confirmed the presence of three prymnesin variants but also measured their direct concentrations before and after HP application.

The experiment, which consisted of two stages, first aimed to assess the effectiveness of HP in combating a P. parvum bloom and to investigate the effects of different HP concentrations on other phytoplankton and prymnesin concentrations (PRMs). The second stage aimed to examine the renewal of the phytoplankton community after HP treatment. We hypothesized that HP, being more toxic to P. parvum than to other eukaryotic algae, would eliminate this haptophyte. The second hypothesis was that using HP would not significantly increase prymnesin concentrations in the water due to HP’s oxidative properties. The third hypothesis posited that after HP treatment, phytoplankton would regenerate with a new supply of water containing a phytoplankton inoculum.

2. Materials and Methods

Water samples for the first stage of the experiment were collected from the Gliwice Canal on 12 April 2023 and sent to the University of Warsaw laboratory. The Gliwice Canal, which discharges high-conductivity water into the Odra River, is the first water body where fish kills were observed during the 2022 P. parvum blooms and where golden alga blooms were observed throughout most of the winter and spring of 2023.

Four tanks, each with a volume of 40 L, were filled with water from the Gliwice Canal with a bloom of Prymnesium parvum. The tanks were equipped with light bulbs designed for plant growth, which remained continuously illuminated. The experimental design included a control (C) and three treatments with increasing concentrations of HP (Warchem, Zakręt, Poland). The treatments were as follows: treatment 1 (T1)—14 mg H2O2/L; treatment 2 (T2)—28 mg H2O2/L; and treatment 3 (T3)—42 mg H2O2/L. The control consisted solely of canal water samples containing phytoplankton and the P. parvum bloom. The first stage lasted 12 days (from S1;D0 to S1;D12). On 24 April 2023, the first day of the second stage (S2;D0), approximately 15 L of water was removed and replaced with 15 L of unfiltered canal water, collected earlier that day, containing the P. parvum bloom (4.6 × 107 cells/L) to study the renewal of the phytoplankton community. Water for the second stage was collected. The experiment continued until May 9 (S2;D15) in the second stage. To examine the abundance of P. parvum, phytoplankton structure, and total biomass, samples were initially collected daily and then every 1 to 3 days. We also measured prymnesin concentrations [nM] in filtered water samples (dissolved PRMs) and on filters (cell-bound PRMs) daily from S1;D0 to S1;D5, and again on S2;D15, the last day of the second stage. Throughout the experiment, we monitored abiotic parameters, including pH, electrical conductivity (EC), temperature, and H2O2 levels.

Phytoplankton samples were fixed with Lugol’s solution and stored in the dark at 4 °C until analysis. Analyses of phytoplankton and

P. parvum were performed using an inverted Nikon Eclipse TS100 microscope following the Utermöhl method [

22]. Between 2.5 and 25 mL of samples was analyzed, depending on the expected number of phytoplankton cells, and between 10 and 40 fields were examined. The biomass of identified taxa was calculated using a geometric approach and converted to wet weight (mg/L) [

23].

Abiotic parameters were measured using Hach

® EC, temperature, and pH probes (Loveland, CO, USA). The initial concentration of HP was determined by a spectrophotometric method using potassium titanium (IV) oxalate [

24]. To monitor changes in H

2O

2, Quantofix

® Peroxide 100 testing strips from Macherey-Nagel GmbH & Co. (Düren, Germany) were used.

The presence and concentrations of prymnesins were analyzed in filtered water (dissolved PRM) and cell-bound prymnesins (cell-bound PRM) collected on GF/C filters using the LC-MS/MS method and were quantified with a recently obtained standard for prymnesins [

14]. The material accumulated on the filters was extracted with 100% methanol. For the analysis of prymnesins in water samples, solid-phase extraction was performed on preconditioned C8 cartridges (0.5 g; BEKOlut, Bruchmühlbach-Miesau, Germany). The sorbed toxins were eluted with 100% methanol. Both extracts were concentrated and analyzed using an LC-MS/MS system equipped with a Waters Acquity H-Class UPLC (Waters, Milford, MA, USA) coupled to a hybrid triple quadrupole mass spectrometer, QTRAP5500 (Sciex, Toronto, ON, Canada). For chromatographic separation, an Acquity CSH C18 column (1.7 µm, 2.1 × 100 mm) (Waters, Milford, MA, USA) was used, with an eluent composed of a water-acetonitrile mixture containing 0.1% (

v/

v) formic acid. Prymnesins were analyzed by multiple reaction monitoring, as recently described [

14]. The differences in prymnesin concentrations were analyzed using a one-sided paired Student’s

t-test.

3. Results

3.1. Abiotic Parameters

Nominal hydrogen peroxide concentrations varied significantly among the experimental tanks. Initially, concentrations were 14 mg/L in tank T1, 28 mg/L in tank T2, and 42 mg/L in tank T3. These corresponded to measured concentrations over 10, over 30, and less than 100 mg H2O2/L, as determined by testing strips used to monitor HP levels throughout the experiment. The HP concentration fluctuated daily, although the strip’s measurements tended to overestimate the readings slightly. After 24 h, hydrogen peroxide levels dropped sharply in all three tanks, with reductions from the initial measured concentrations to approximately 3 mg/L in T1, below 10 mg/L in T2, and 30 mg/L in T3. After 48 h, HP was only detectable in the tank with the highest initial nominal concentration (>3 mg/L; T3). By the third day, it fell below 1 mg/L and was not detected later. During the experiment, the temperature increased in all tanks from an initial 16 °C to 24 °C by the end of the experiment, with no significant differences between treatments. This rise was attributed to adjusting the water temperature to match the laboratory’s ambient temperature. Electroconductivity (EC) increased from about 3.5 mS/cm at the start to 3.6 mS/cm after the first stage of the experiment, reaching 4 mS/cm on the final day, likely due to evaporation. The pH ranged from 9.63 at the start to 9.18 in T1 and 8.83 in the other treatments by the end of the first stage, stabilizing at 8.84 in the control and 9.14 in T1 by D15.

3.2. Prymnesium parvum Abundance

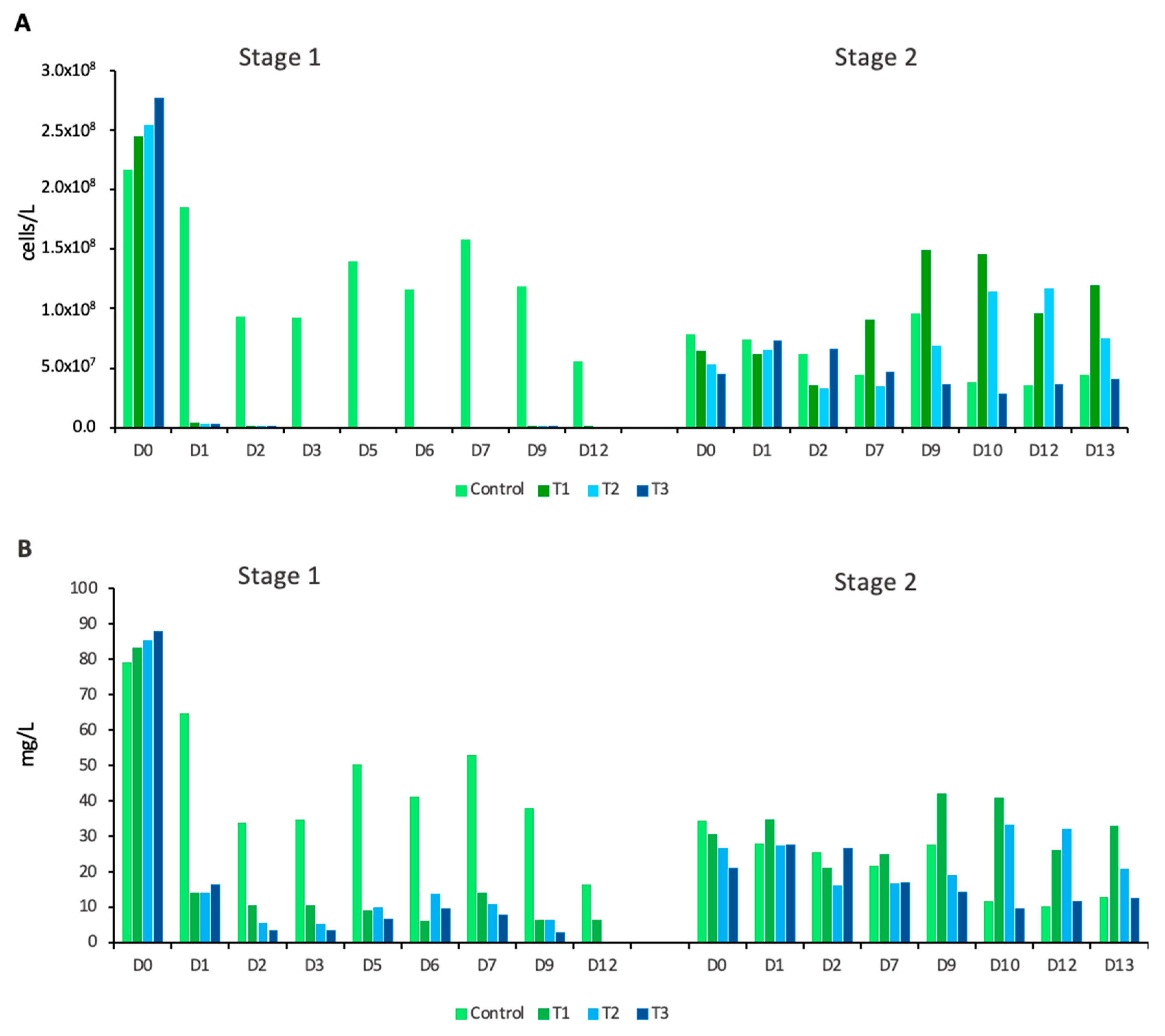

In the first stage of the experiment (S1), we observed a gradual decrease in

P. parvum in the control conditions with slight daily variations (

Figure 1A). The addition of HP resulted in a dramatic reduction in

P. parvum abundance across all three experimental treatments. Within the first 24 h, it decreased by 98.6%, 98.8%, and 99.0% in the tanks with the lowest to the highest initial HP concentrations, respectively. On the third day, no living

P. parvum cells were observed in any of the experimental treatments. Twenty-four hours after HP addition, numerous dead, incompletely lysed

P. parvum cells were observed in all three treatments. The cells were visibly damaged and ruptured, exhibiting impaired chloroplasts. The damaged cells remained in the tanks for another 24 h, after which only very few dead cells were observed in T1.

Prymnesium parvum did not recover in any of the HP treatments until the end of the first part of the experiment (S1;D12). In the second stage of the experiment (S2), following supplementation with a phytoplankton inoculum with a

P. parvum bloom from the canal, the amount of

P. parvum in the control increased briefly before decreasing again, similarly to the first stage. The abundance of

P. parvum in T1 and T2 increased, reaching levels higher than those in the control, whereas in T3, it followed the pattern observed in the control (

Figure 1A).

3.3. Phytoplankton Biomass, Composition, and Structure

Analysis of the entire phytoplankton community revealed that the total biomass of phytoplankton decreased in control conditions from the beginning to the end of the experiment, with a slight increase after the addition of canal water with

P. parvum bloom on S2;D0 (the first day of the second stage) (

Figure 1B). In all experimental treatments, total phytoplankton biomass sharply dropped during the first 24 h following the addition of HP, declining by 83%, 84%, and 81% compared to S1;D0, respectively. Later, in the treatment with the lowest HP concentration, the phytoplankton biomass gradually decreased, reaching about 6.6 mg/L on the final day (S1;D12), just before the addition of new water. In the second and third HP treatments, total phytoplankton biomass decreased sharply to 0.1 and 0.01 mg/L by the last day of the first stage (S1;D12), respectively (

Figure 1B). After adding the phytoplankton inoculum (S2;D0), biomass increased slightly and fluctuated daily. The phytoplankton biomass in the lowest (T1) and medium (T2) HP treatments increased moderately. In contrast, in the treatment with the highest initial HP dose (T3), total phytoplankton biomass followed the same pattern as in the control.

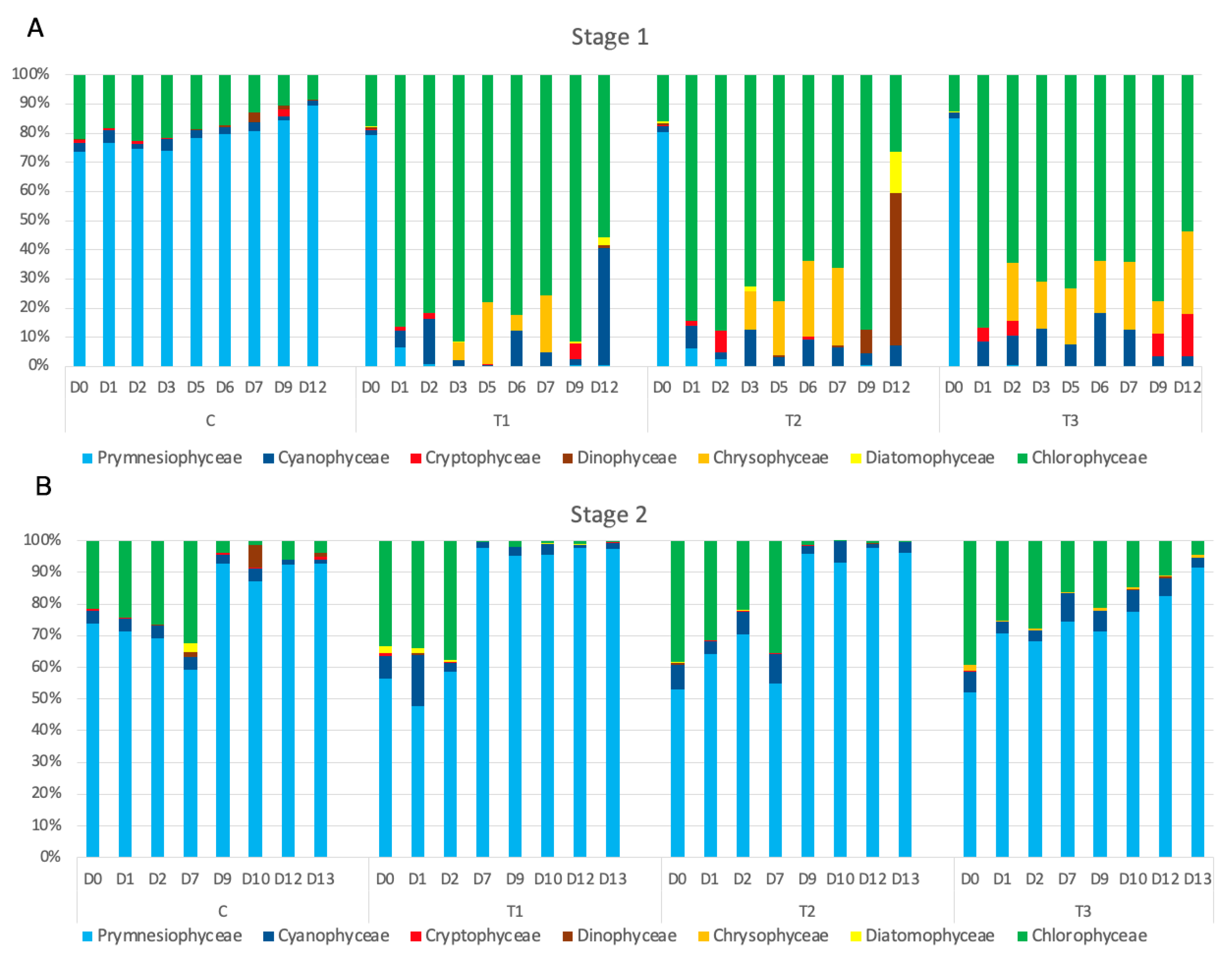

The analysis of phytoplankton composition and structure (

Figure 2A) revealed that at the beginning of the experiment (D0),

P. parvum overwhelmingly dominated the phytoplankton under both control conditions and experimental treatments. Chlorophytes ranked as the second most abundant phytoplankton group by biomass, with key species including

Scenedesmus acuminatus,

Monoraphidium contortum, and

M. minutum. Among the Cyanophyceae,

Planktothrix agardhii and

Pseudanabaena limnetica predominated, while

Panus sp.,

Microcystis incerta, and

Chroococcus sp. were present in lower quantities. Toward the end of the experiment,

P. agardhii and

P. limnetica disappeared from the tanks with HP treatments, although coccal cyanobacteria remained in low numbers. The biomass of green algae and cyanobacteria declined throughout the experiment in both the control and HP treatments. Small, unidentified Chrysophyceae were observed and began to flourish in the experimental treatment tanks, initially at the highest HP concentration (T3) and later in the lower-HP treatments.

In the control, despite the decrease in the total phytoplankton biomass,

P. parvum dominated the community throughout the experiment, increasing its contribution over time, mainly at the expense of green algae (

Figure 2A). In the three HP treatments, after the retreat of the haptophyte, green algae dominated the phytoplankton with a contribution of around 80% in T1. A subsequent decrease in the share of green algae was observed, to about 75% in T1, 66% in T2, and 55% in T3. This decline was related to an increase in small, unidentified Chrysophyceae. The contribution of Cyanophyceae also increased following the collapse of the

P. parvum bloom, especially in the treatment with the highest HP concentration; however, as mentioned above, their biomass did not increase. After the addition of the new inoculum (

Figure 2B), the contribution of

P. parvum varied between 53% and 71%. Within a few days, it reached 97–93% in T1 and T2 and 87% T3.

3.4. Concentration of Prymnesins

Throughout the experiment, only type B prymnesins were identified, represented by three variants described below. Here, we describe the summarized concentrations of all three variants, cell-bound and in water. In the control, the concentration of cell-bound prymnesins increased from 535 nM (S1;D0) to 1230 nM (S1;D5). However, a drop in this fraction of prymnesins was observed between S1;D2 and S1;D3. On the final day of the second stage of the experiment (S2;D15), the cell-bound PRM concentration was higher than at the beginning of the experiment (844 nM). The concentration of PRMs in water varied less than the cell-bound ones, increasing from 476 nM on S1;D0 to 962 nM (S1;D5). The concentration at the end of the experiment was similar to the beginning (S2;D15; 478 nM) (

Figure 3). In general, cell-bound PRM concentrations were higher than dissolved PRMs, apart from S1;D2 and S1;D3, and the total concentration of prymnesins under control conditions was lowest on S1;D0 and highest on S1;D5.

In all treatments with HP, the concentrations of both dissolved and cell-bound prymnesins decreased significantly within the first 24 h. In every instance, even when P. parvum was no longer observed (S1;D5), low levels of prymnesins remained detectable on the filters, possibly bound to seston. In T1, the cell-bound concentration of prymnesins ranged from 194 nM to 29 nM, with 40 nM on S1;D5. The dissolved prymnesin concentration was higher than that of cell-bound prymnesins in this treatment, but gradually declined from 822 to 109 nM.

In T2 and T3, dissolved PRMs were also higher, being twice as high on S1;D5 compared to T1. In both treatments, cell-bound prymnesins were slightly higher than in T1, ranging between 32 and 274 in T2 and between 55 nM and 247 T3. On day 5 (S1;D5), PRMs in the experimental treatments accounted for 8% to 17% in the cell-bound fraction and 23% to 43% in the water fraction, compared to S1;D0. The differences between the three experimental tanks were not statistically significant, while all three were significantly lower than in the control (p > 0.05). At the end of the second stage of the experiment (S2;D15), the highest concentrations of cell-bound and dissolved PRMs were observed in T1, reaching 3215 nM and 2210 nM, respectively. In T2, the cell-bound concentration was 2382 nM and 897 nM in water, while in T3, the values were close to those in the control: 742 nM cell-bound and 492 nM in water.

A detailed analysis of the prymnesin profile revealed three variants of B-type PRMs: PRM 990 (PRM B (1 × Cl + 2 × hexose), PRM 909 (PRM B (1 × Cl + 1 × hexose) and PRM 828 (PRM B (1 × Cl) (

Figure 3). At the start of the experiment, S1;D0, the contributions of PRM 909 and PRM 828 were equal in the cell-bound fraction, while in water, PRM 828 dominated. Throughout the experiment, under control conditions, the PRM 909 variant primarily appeared in cells and water; however, from S1;D1 onward, we observed the emergence of the third variant, PRM 990, which significantly contributed to the total PRM concentration in cells at S1;D4 and S1;D5. This variant was also present on the final day of the second stage of the experiment, co-dominating in cells.

In experimental HP treatments, PRM 828 predominated primarily in the cell-bound fraction and water until D5. However, on the last day of the second stage (S2;D15), the third variant (PRM 990) was observed in all experimental treatment tanks, contributing significantly to total prymnesins in cells and, to a lesser extent, in water. We also calculated the concentrations of PRMs per cell under control conditions, after HP treatment, and after introducing the new inoculum of phytoplankton with the P. parvum bloom in both the control and experimental treatments. Following HP treatment until S1;D3, the concentration of PRMs per cell decreased in all experimental treatments compared to the control. When the number of P. parvum cells fell nearly to 0, the concentrations per cell increased, although they remained very low. Compared to the beginning and the end of the experiment, we found that in both the control and experimental treatments, the concentration of PRMs per cell was higher after adding the new inoculum than at the start. PRMs per cell ranged from nine times higher in T1 to three times higher in T2 and up to six times higher in T3 and in the control. However, the PRMs per cell on the last day (S2;D15) in T1 and T2 reached about 1.5 times those in the control, while in T3 the concentration per cell was similar to that in the control.

4. Discussion

Our experiment combating

P. parvum blooms with hydrogen peroxide (HP) demonstrated that H

2O

2 effectively eliminated

P. parvum across all three nominal concentrations: 14, 28, and 42 mg H

2O

2/L. Until now, HP has primarily been used to combat cyanobacterial blooms, with varying concentrations applied depending on the targeted taxa and environmental conditions. Typically, HP doses range from 2 to 5 mg H

2O

2/L, although concentrations up to 10 mg H

2O

2/L have also been used [

25,

26,

27]. In the Netherlands, where several water bodies have been treated with HP, a concentration of 2 mg/L effectively eliminated

Planktothrix agardhii, while 5 mg/L proved effective for

Microcystis aeruginosa.

Drábkova et al. conducted a laboratory experiment that found that green algae and diatoms were resistant to HP concentrations 10 times higher than those used to control cyanobacteria (2 mg/L) [

28]. Additionally, other authors observed in a whole-lake experiment that a concentration of 2.5 mg/L of HP used against cyanobacteria was not harmful to eukaryotic algae, resulting in a shift in the phytoplankton community toward green algae and cryptophyte dominance at the expense of cyanobacteria [

25]. The authors also demonstrated that this dose did not adversely affect other components of the aquatic food web. A study using sodium carbonate peroxyhydrate to combat

Microcystis aeruginosa showed that this cyanobacterial species was more sensitive to HP than the non-target eukaryotic alga species

Pseudokirchneriella subcapitata [

29]. Hydrogen peroxide has also been shown to be an effective treatment against filamentous cyanobacterial species of the genera

Anabaena,

Cylindrospermopsis, and

Planktothrix, with species-specific sensitivity [

30]. Using a gradient design field experiment, it was found that H

2O

2 doses >1.3 mg/L significantly reduced cyanobacteria while promoting other phytoplankton taxa, including chlorophytes. These results indicate that eukaryotic algae are more resistant to HP than cyanobacteria, suggesting that if eukaryotes are to be targeted, higher doses should be employed. Consequently, when HP was used against eukaryotic algae, dinophytes [

31], and

P. parvum [

19], concentrations of approximately 40–50 mg H

2O

2/L were applied. However, even higher HP doses, ranging from 62 to 500 mg/L, have been used to eliminate

P. parvum in breeding fishponds [

18]. The authors of [

19], testing HP in the laboratory and later in a natural setting in the Norfolk Broads, UK, demonstrated that using 40–50 mg H

2O

2/L resulted in a substantial decrease in

P. parvum within six hours, with levels remaining very low for 24 h. However, after 96 h, the abundance measured by ITS copy numbers increased to levels observed in control locations.

In our laboratory experiment, we tested 42 mg/L of HP as the highest concentration; however, we also examined lower concentrations of 14 and 28 mg/L. Using a natural phytoplankton community with a pronounced bloom of P. parvum, we demonstrated that even the lowest concentration effectively removed nearly 99% of haptophyte cells within the first 24 h. The abundance of live cells decreased similarly rapidly across all three H2O2 concentrations, and differences between the HP doses became evident in the faster breakdown and lysis of dead cells in the T2 and T3 compared to the lowest HP concentration (T1). HP was undetectable in water three days after application, but P. parvum did not recover in any of the experimental tanks.

While examining the effects of HP on other phytoplankton components, we found that HP negatively influenced filamentous cyanobacteria and green algae in particular, and these effects persisted even after HP was no longer detectable. However, due to the dramatic decline in

P. parvum, the contributions of other phytoplankton groups, including cyanobacteria, increased in the experimental treatments. Total phytoplankton biomass decreased, especially in T2 and T3, demonstrating that HP concentrations of about 30 and 40 mg H

2O

2/L are harmful to all phytoplankton. In contrast, a dose of 14 mg H

2O

2/L (T1) appears safe for other phytoplankton taxa but effective against

P. parvum blooms. The higher sensitivity of

P. parvum to HP may be attributed to the absence of a true outer cell wall. Instead, this species is covered with two layers of ornate, plate-like cellulosic scales [

31], which might provide less protection due to increased permeability. However, further research is needed to understand why

P. parvum is more sensitive to HP than other algae. This supports the first hypothesis that HP can combat

P. parvum, as it is more toxic to this haptophyte than to other algae, such as green algae.

However, a laboratory experiment on the influence of sodium percarbonate (which releases H

2O

2) on zooplankton [

32] and HP in laboratory and field trials [

33] demonstrated that a HP concentration between 20 and 30 mg H

2O

2/L can be harmful to zooplankton, with Cladocera being more susceptible than Copepoda. Adverse effects on all zooplankton groups at an H

2O

2 concentration of 20 mg/L, and a particular sensitivity of rotifers at lower doses, were observed by Yang et al. [

30]. Concerning fish, harmful doses of HP are higher than those for cyanobacteria, eukaryotic algae, and zooplankton [

19,

26,

27,

28,

29,

32,

33,

34,

35]. Hydrogen peroxide is used in fishponds and aquaculture as a disinfectant, among other uses, against pathogenic fungi; it has been found that a concentration of 25 mg/L enhances hatching rates without affecting fish mortality [

35]. In another study [

28], HP at 50 mg/L for 48 h did not induce adverse effects in fish. To summarize, the use of HP to eliminate

P. parvum blooms can be effective in protecting fish and mollusk populations from the harmful effects of prymnesins and other toxins released by

P. parvum. However, a balance between the gains for one population and the losses to others must be considered.

The sudden release of toxins into water following algicidal treatments remains a concern in bloom control, as it can cause severe ecological damage. This was observed in a case of cylindrospermopsin intoxication following the application of an algicide to control a cyanobacterial bloom in Palm Island, Australia [

36]. The mechanisms by which toxins are released from

Prymnesium parvum cells are not fully understood. However, it is believed that prymnesins may leak into the surrounding water due to cell damage or mortality [

37,

38]. This heightens the threat to aquatic environments and efforts to reduce blooms by lowering

P. parvum populations. A key finding of our study is that after applying HP and observing the dramatic collapse of

P. parvum, we did not see an increase in prymnesin levels in either the cells or the water. In fact, the levels of cell-bound toxins and those in water were much lower in the experimental treatments than in the D0) and in control conditions across all days of the first stage of the experiment. It seems that the hydrogen peroxide used to control the bloom not only killed

P. parvum but also broke down the toxins. Likewise, earlier research on cyanobacterial bloom control using HP [

25] showed that the detrimental side effect of increased toxin levels was not observed with microcystins.

Interestingly, cell-bound prymnesins could be measured after live or dead

Prymnesium cells were no longer present in the experimental tanks. It appears that prymnesins released from

P. parvum cells may have been adsorbed onto the seston collected on the filters, as observed for microcystins in Mexican waters [

39]. The concentrations of prymnesins in the water of the HP treatment tanks exceeded cell-bound concentrations, and, similar to the latter, they seemed to be higher in the two treatments with larger HP additions than in the treatment with the lowest concentration. Although the differences in concentration were not statistically significant, they indicate that the lowest initial HP concentration was sufficient to limit both the numbers and biomass of

P. parvum and to mitigate the adverse effects of toxins produced by these algae. We also observed that during the experiment, the concentrations of toxins in water in the control increased similarly to those in the experimental treatments and were higher than cell-bound concentrations. This may suggest an enclosure effect and potential stress on

P. parvum, leading to increased toxin release into the water. However, it is essential to reiterate that after the addition of HP, prymnesin levels in the experimental treatments were significantly lower than at the beginning of the experiment and under control conditions. This supports the second hypothesis: that the oxidative properties of HP inhibit the increase in prymnesin concentrations following cellular release—an effect itself triggered by the addition of HP.

Adding the phytoplankton inoculum with the

P. parvum bloom to all tanks aimed to determine whether, after HP treatment and once HP was no longer detectable, the phytoplankton community could be revived with a new inoculum. This stage of the experiment resulted in an increase in total phytoplankton biomass, supporting the third hypothesis that after HP treatment, phytoplankton would regenerate with a new supply of phytoplankton inoculum. Nonetheless, an increase in

P. parvum contribution to total phytoplankton biomass was observed across all tanks. The dominance of

P. parvum in both control and experimental treatments could be linked to the fact that the introduced phytoplankton inoculum contained a

P. parvum bloom, giving the haptophyte a competitive edge. The prymnesin profile, along with the prymnesin concentrations per haptophyte cell, changed in all treatments, including the control. In the PRM profile, we observed the prymnesin variant PRM 990 in the experimental treatments, where it was either entirely absent or previously detected at very low levels. The concentrations of PRM 990 in T1 and T2 were also significantly higher than at the start of the experiment (S1;D0) and in the control on S2;D15. This suggests that between the beginning of the experiment (S1;D0, 12.04.25) and the addition of water with inoculum (S2;D0, 24.04), a new

P. parvum population characterized by a distinct PRM profile emerged in the environment. It is worth noting that PRM concentrations per cell were also higher during the second stage of the experiment in the control and all treatments, supporting the supposition of population changes in

P. parvum. However, a shift in the prymnesin profile within cells was also observed toward the end of the first part of the experiment in the control, indicating a change in the chemotype components of the

P. parvum population. Similarly, a change in prymnesin profiles was also observed in an experimental study with three strains of

P. parvum [

40]. The authors demonstrated that the growth phase and salinity influenced the prymnesin profile, although the response to changing conditions was species-specific. In our experiment, changes in salinity were not significant. Still, the permanent illumination and/or interactions within the phytoplankton community could be responsible for the observed changes.

An intriguing result of the experiment is that, in the treatment with the lowest HP concentration, upon addition of a new inoculum containing the P. parvum bloom, we observed the most significant increase in haptophyte abundance, accompanied by the highest toxin concentrations. This outcome is counterintuitive, as we expected the tank with the highest initial concentration of HP and the lowest final phytoplankton biomass at the end of stage 1 (S1) to create the best conditions—through high nutrient concentrations and low competition—for the growth of the new phytoplankton inoculum. The reason for this unexpected result warrants further investigation.