Distribution of 210Pb and 210Po and Particulate Organic Carbon (POC) Fluxes in the Northwestern Pacific Ocean in Summer 2024

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

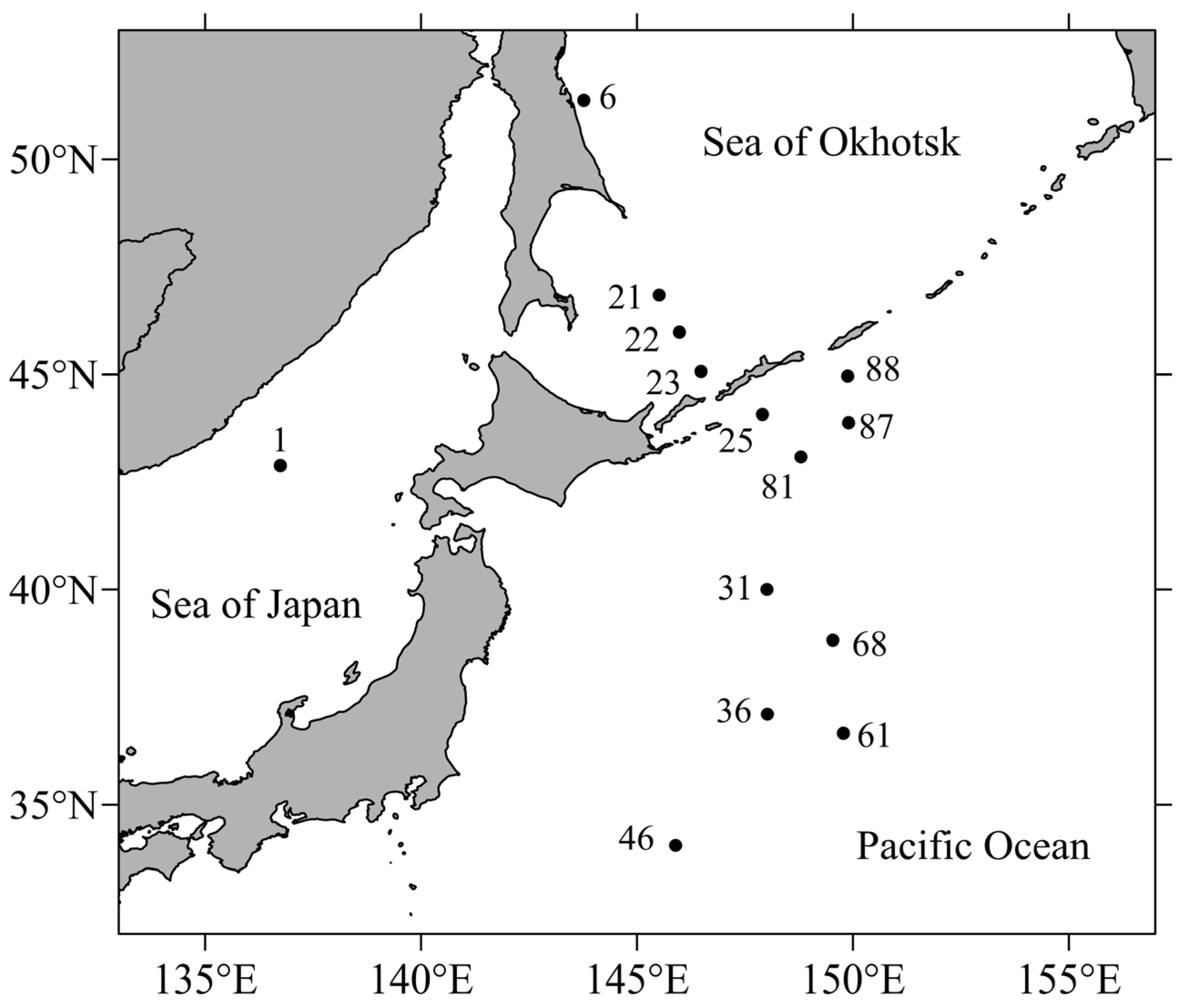

2.1. Sampling and Filtration

2.2. Hydrological Survey

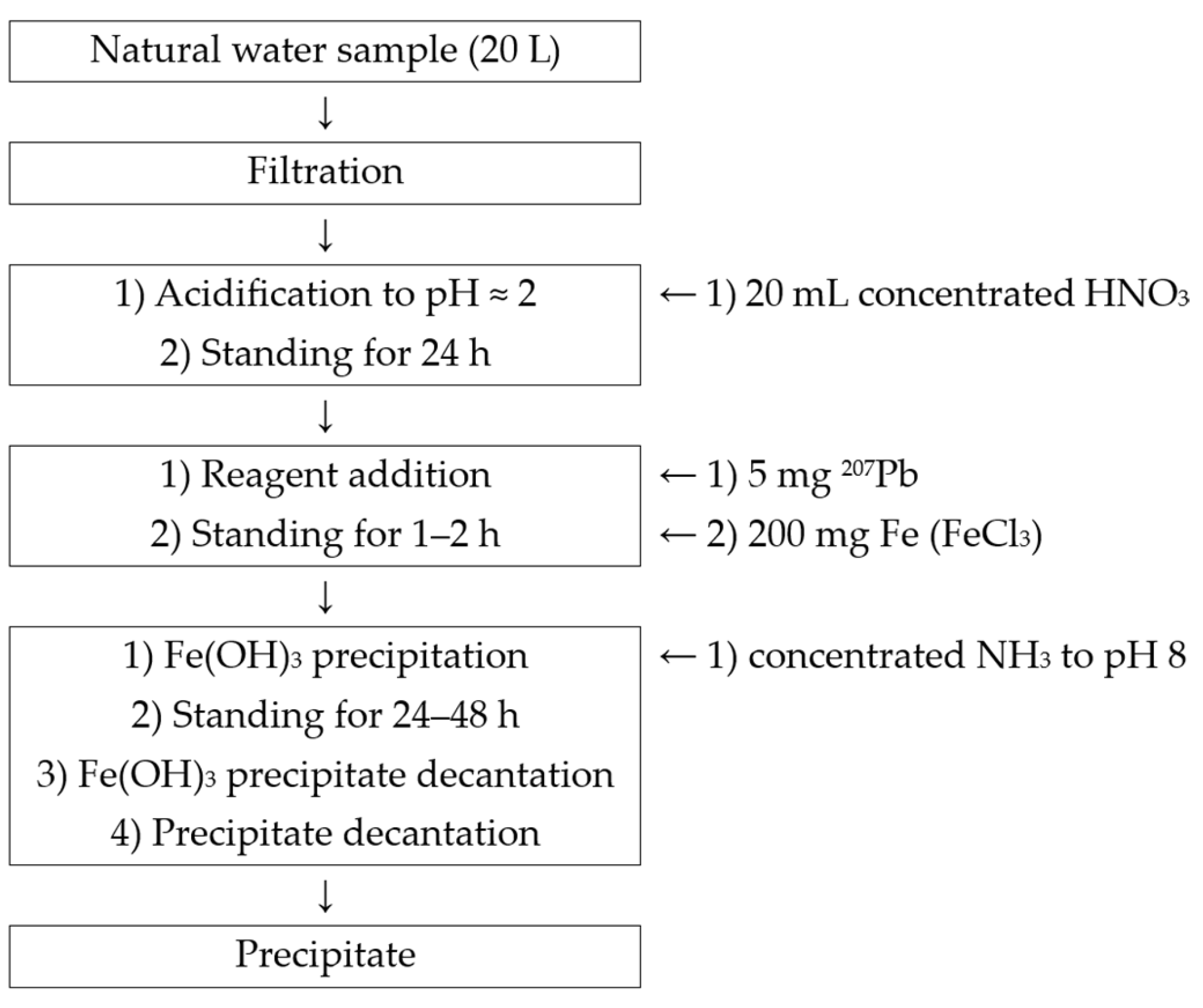

2.3. Concentration of Dissolved Forms of 210Pb and 210Po

2.4. Determination of 210Pb and 210Po Activity by Alpha-Spectrometry and Radiometric Method After Radiochemical Preparation

2.5. Determination of POC Concentration

2.6. Calculation of SPM and POC Fluxes

3. Results and Discussion

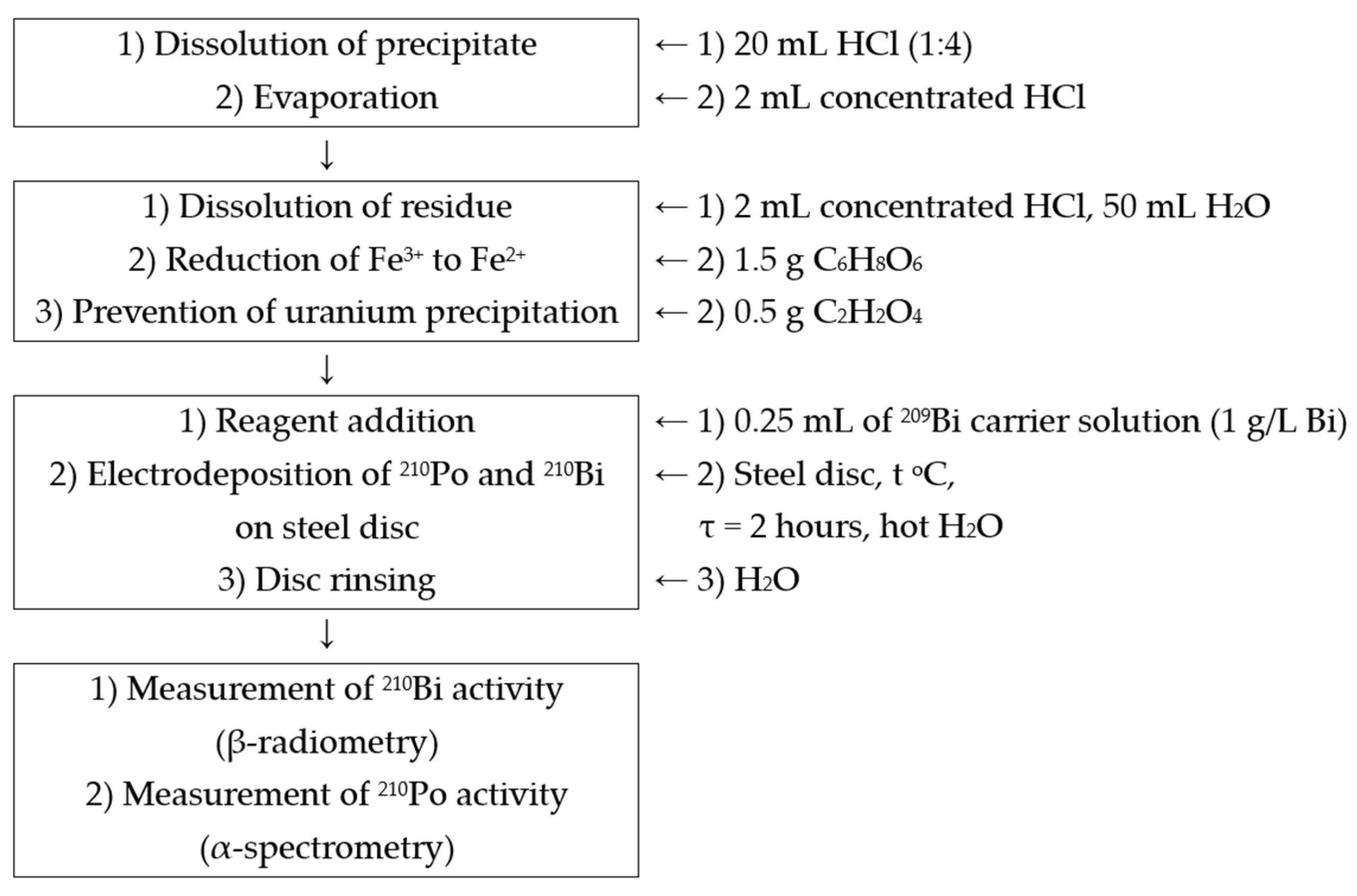

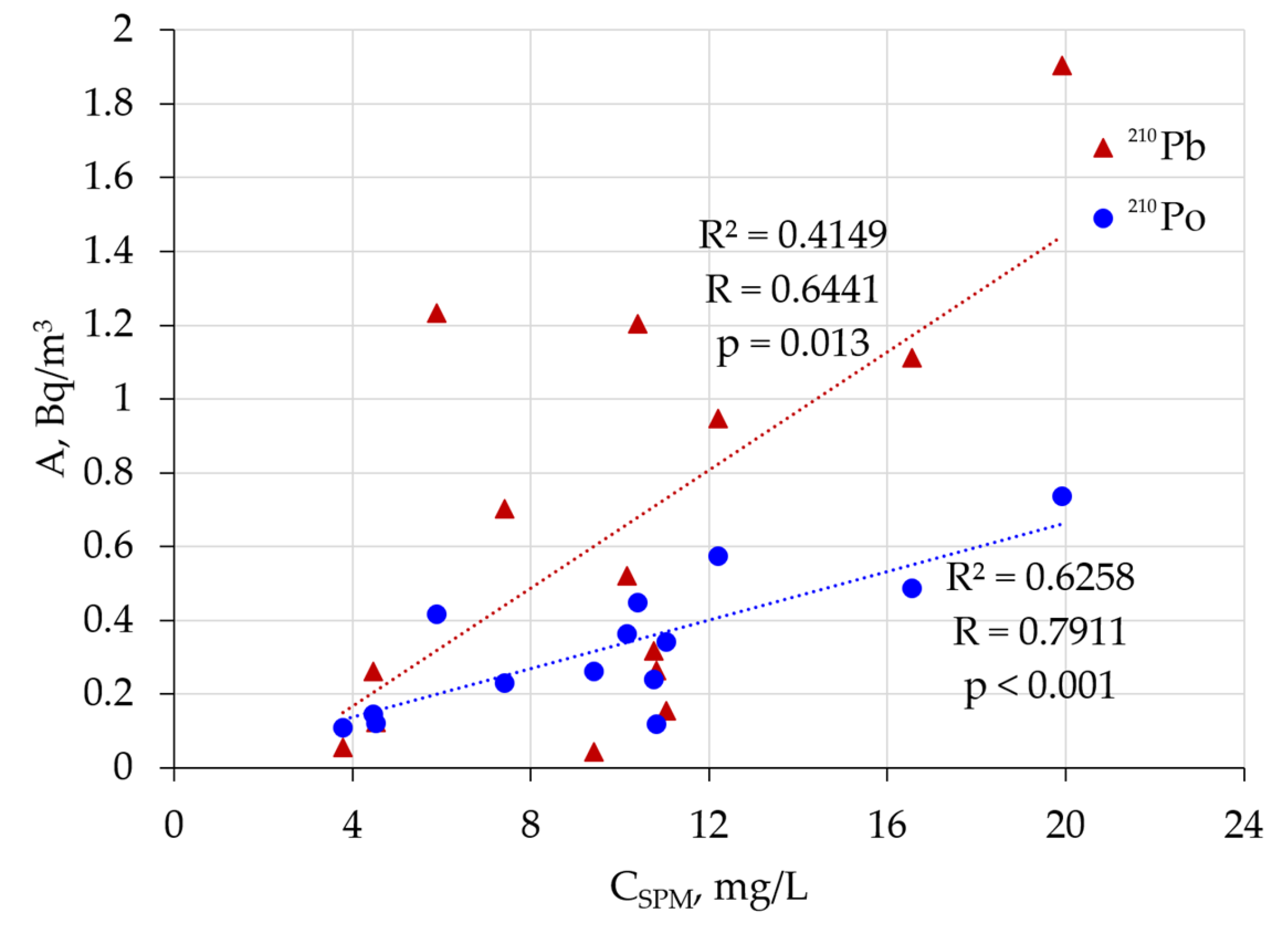

3.1. Distribution of 210Pb and 210Po

3.2. Fluxes of SPM and POC

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CTD | Conductivity, Temperature, Depth |

| POC | Particulate Organic Carbon |

| R/V | Research Vessel |

| SPM | Suspended Particulate Matter |

References

- Sanitary Rules 2.6.1.2612-10; Basic Sanitary Rules for Radiation Safety (OSPORB-99/2010). Federal Service for Surveillance on Consumer Rights Protection and Human Wellbeing (Rospotrebnadzor): Moscow, Russia, 2010. (In Russian)

- Sanitary Rules and Norms SanPiN 2.6.1.2523-09; Radiation Safety Standards (NRB-99/2009). Federal Center for Hygiene and Epidemiology of Rospotrebnadzor: Moscow, Russia, 2009. (In Russian)

- Villa-Alfageme, M.; Mas, J.L.; Hurtado-Bermudez, S.; Masqué, P. Rapid determination of 210Pb and 210Po in water and application to marine samples. Talanta 2016, 160, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdeny, E.; Masqué, P.; Garcia-Orellana, J.; Hanfland, C.; Cochran, J.K.; Stewart, G.M. POC export from ocean surface waters by means of 234Th/238U and 210Po/210Pb disequilibria: A review of the use of two radiotracer pairs. Deep Sea Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 2009, 56, 1502–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.Y.; Stewart, G.; Lomas, M.W.; Kelly, R.P.; Moran, S.B. Linking the distribution of 210Po and 210Pb with plankton community along Line P, Northeast Subarctic Pacific. J. Environ. Radioact. 2014, 138, 390–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subha Anand, S.; Rengarajan, R.; Shenoy, D.; Gauns, M.; Naqvi, S.W.A. POC export fluxes in the Arabian Sea and the Bay of Bengal: A simultaneous 234Th/238U and 210Po/210Pb study. Mar. Chem. 2017, 198, 70–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, C.T.; Black, E.E.; Anderson, R.F.; Baskaran, M.; Buesseler, K.O.; Charette, M.A.; Cheng, H.; Kirk Cochran, J.; Lawrence Edwards, R.; Fitzgerald, P.; et al. Flux of particulate elements in the North Atlantic Ocean constrained by multiple radionuclides. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycl. 2018, 32, 1738–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, H.; Krishnaswami, S.; Somayajulu, B.L.K. Lead-210–radium-226. Radioactive disequilibrium in the deep sea. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1973, 17, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, G.M.; Bradley Moran, S.; Lomas, M.W. Seasonal POC fluxes at BATS estimated from 210Po deficits. Deep Sea Res. Part I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 2010, 57, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducklow, H.D.; Steinberg, D.K.; Buesseler, K.O. Upper ocean carbon export and the biological pump. Oceanography 2001, 14, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feely, R.A.; Sabine, C.L.; Takahashi, T.; Wanninkhof, R. Uptake and storage of carbon dioxide in the oceans: The global CO2 survey. Oceanography 2001, 14, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berelson, W.M.; Johnson, K.; Coale, K.; Li, H.-C. Organic matter diagenesis in the sediments of the San Pedro Shelf along a transect affected by sewage effluent. Cont. Shelf Res. 2002, 22, 1101–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eppley, R.W.; Peterson, B.J. Particulate organic matter flux and planktonic new production in the deep ocean. Nature 1979, 282, 677–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacon, M.P.; Spencer, D.W.; Brewer, P.G. 210Pb/226Ra and 210Po/210Pb disequilibria in seawater and suspended particulate matter. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1976, 32, 277–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Soto, F.; Ceballos-Romero, E.; Villa-Alfageme, M. A microscopic simulation of particle flux in ocean waters: Application to radioactive pair disequilibrium. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2018, 239, 136–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceballos-Romero, E.; Le Moigne, F.A.C.; Henson, S.; Marsay, C.M.; Sanders, R.J.; García-Tenorio, R.; Villa-Alfageme, M. Influence of bloom dynamics on particle export efficiency in the North Atlantic: A comparative study of radioanalytical techniques and sediment traps. Mar. Chem. 2016, 186, 198–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrich, J.; Rutgers van der Loeff, M.M. A two-tracer (210Po–234Th) approach to distinguish organic carbon and biogenic silica export flux in the Antarctic circumpolar current. Deep Sea Res. Part I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 2002, 49, 101–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarin, M.M.; Guebuem, K.; Church, T.M. 210Po and 210Pb in the South-equatorial Atlantic: Distribution and disequilibrium in the upper 500 m. Deep Sea Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 1999, 46, 907–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.; Church, T.M. Seasonal biogeochemical fluxes of 234Th and 210Po in the upper Sargasso Sea: In fluence from atmospheric iron deposition. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycl. 2001, 15, 651–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran, J.K.; Wei, Z.; Horowitz, E.; Fitzgerald, P.; Heilbrun, C.; Stephens, M.; Lam, P.J.; Le Roy, E.; Charette, M. 210Po and 210Pb distributions along the GEOTRACES Pacific Meridional Transect (GP15): Tracers of scavenging and particulate organic carbon (POC) export. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycl. 2024, 38, e2024GB008243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, J.W.; Paul, B.; Dunne, J.P.; Chapin, T. 234Th, 210Pb, 210Po and stable Pb in the Central Equatorial Pacific: Tracers for particle cycling. Deep Sea Res. Part I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 2005, 52, 2109–2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bam, W.; Maiti, K.; Baskaran, M. 210Po and 210Pb as tracers of particle cycling and export in the Western Arctic Ocean. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 697444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Q.; Li, L.; Puigcorbé, V.; Huang, D.; Yu, T.; Du, J. Contrasting behaviors of 210Po, 210Pb and 234Th in the East China Sea during a severe red tide: Enhanced scavenging and promoted fractionation. Acta Oceanol. Sin. 2022, 41, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Zhao, X.; Guo, L.; Huang, B.; Chen, M.; Fang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Qiu, Y. Utilization of Soot and 210Po-210Pb disequilibria to constrain particulate organic carbon fluxes in the northeastern South China Sea. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 694428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Liu, X.; Ren, C.; Jia, R.; Qiu, Y.; Zheng, M.; Chen, M. 210Po/210Pb disequilibria and its estimate of particulate organic carbon export around Prydz Bay, Antarctica. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 701014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Chen, M.; Zheng, M.; Qiu, Y.; Chen, Q.; Li, Q. 210Po/210Pb disequilibria influenced by production and remineralization of particulate organic matter around Prydz Bay, Antarctica. Deep Sea Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 2021, 191–192, 104961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frolova, M.A.; Bezhin, N.A.; Slizchenko, E.V.; Kozlovskaia, O.N.; Tananaev, I.G. Assessment of Seasonal Variability in Phosphorus Biodynamics by Cosmogenic Isotopes 32P, 33P around Balaklava Coast. Materials 2023, 16, 1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betenekov, N.D. Radioecological Monitoring: A Textbook; Ural University Press: Yekaterinburg, Russia, 2014. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- All-Russian Scientific-Research Institute of Mineral Resources named after N.M. Fedorovsky. Procedure for Measuring the Volumetric Activity of Polonium-210 (210Po) and Lead-210 (210Pb) in Natural (Fresh and Mineralized), Process, and Waste Water Samples by Alpha-Beta Radiometric Method with Radiochemical Preparation; All-Russian Scientific-Research Institute of Mineral Resources named after N.M. Fedorovsky: Moscow, Russia, 2021. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Buesseler, K.O. Do upper-ocean sediment traps provide an accurate record of particle flux? Nature 1991, 353, 420–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulin, S.B.; Samyshev, E.Z.; Stokozov, N.A.; Sysoev, A.A. Assessment of sedimentation rate of the suspended matter from superficial layer of water of the Bransfield strait (Western Antarctic) with the use of Thorium-34 as natural radiotrasser. Ukr. Antarct. J. 2003, 1, 30–36. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roca-Martí, M.; Puigcorbé, V.; Rutgers van der Loeff, M.M.; Katlein, C.; Fernández-Méndez, M.; Peeken, I.; Masqué, P. Carbon export fluxes and export efficiency in the central Arctic during the record sea-ice minimum in 2012: A joint 234Th/238U and 210Po/210Pb study. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2016, 121, 5030–5049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roca-Martí, M.; Puigcorbé, V.; Castrillejo, M.; Casacuberta, N.; Garcia-Orellana, J.; Cochran, J.K.; Masqué, P. Quantifying 210Po/210Pb Disequilibrium in Seawater: A Comparison of Two Precipitation Methods with Differing Results. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 684484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Q.; Yu, T.; Lin, H.; Lin, J.; Ji, J.; Ni, J.; Du, J.; Huang, D. 210Po–210Pb Disequilibrium in the Western North Pacific Ocean: Particle Cycling and POC Export. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 700524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, H.; Joung, D.; Kim, G. Contrasting Behaviors of 210Pb and 210Po in the Productive Shelf Water Versus the Oligotrophic Water. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 701441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buesseler, K.O.; Benitez-Nelson, C.R.; Moran, S.B.; Burd, A.; Charette, M.; Cochran, J.K.; Coppola, L.; Fisher, N.S.; Fowler, S.W.; Gardner, W.D.; et al. An assessment of particulate organic carbon to thorium-234 ratios in the ocean and their impact on the application of 234Th as a POC flux proxy. Mar. Chem. 2006, 100, 213–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Station No. * | Coordinates | Depth (m) | T (°C) | S (‰) | Chlorophyll Fluorescence (mg/m3) | A 210Pb (Bq/m3) | A 210Po (Bq/m3) | CSPM (mg/L) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lat. (N) | Long. (E) | Diss. | Part. | Diss. | Part. | ||||||

| 1 | 136.74049 | 42.88050 | 5 | 10.8067 | 33.9373 | 24.28 | 4.32 ± 0.43 | 0.263 ± 0.026 | 0.30 ± 0.07 | 0.119 ± 0.012 | 10.8264 |

| 27 | 8.0633 | 33.9610 | 84.42 | 5.26 ± 0.53 | 0.464 ± 0.046 | 0.49 ± 0.11 | 0.498 ± 0.050 | 18.9233 | |||

| 40 | 6.0781 | 34.0110 | 21.60 | 5.37 ± 0.54 | 0.437 ± 0.044 | 0.32 ± 0.08 | 0.482 ± 0.048 | 18.2654 | |||

| 6 | 143.76805 | 51.36921 | 5 | 1.1533 | 31.6295 | 9.14 | 4.93 ± 0.49 | 0.702 ± 0.070 | 1.04 ± 0.14 | 0.230 ± 0.026 | 7.4075 |

| 20 | −0.1179 | 32.0683 | 30.49 | 4.28 ± 0.43 | 0.045 ± 0.009 | 0.30 ± 0.08 | 0.047 ± 0.010 | 12.8219 | |||

| 21 | 145.51447 | 46.84548 | 5 | 6.9583 | 32.5678 | 104.7 | 4.43 ± 0.44 | 1.904 ± 0.190 | 1.05 ± 0.15 | 0.737 ± 0.074 | 19.9269 |

| 22 | 145.98249 | 45.98332 | 5 | 8.4107 | 32.3414 | 7.40 | 4.51 ± 0.45 | 0.122 ± 0.013 | 0.50 ± 0.11 | 0.120 ± 0.013 | 4.5184 |

| 20 | 3.4998 | 32.3457 | 60.26 | 4.64 ± 0.46 | 0.727 ± 0.073 | 0.43 ± 0.12 | 0.250 ± 0.030 | 11.9668 | |||

| 40 | −0.7164 | 32.7263 | 4.39 | 4.20 ± 0.42 | 0.571 ± 0.057 | 0.64 ± 0.11 | 0.054 ± 0.020 | 11.1527 | |||

| 23 | 146.48012 | 45.06959 | 5 | 9.0408 | 32.4497 | 11.95 | 4.80 ± 0.48 | 0.521 ± 0.052 | 0.68 ± 0.12 | 0.362 ± 0.042 | 10.1514 |

| 30 | 4.1246 | 32.8411 | 47.16 | 4.53 ± 0.45 | 0.181 ± 0.021 | 0.77 ± 0.14 | 0.158 ± 0.020 | 13.6434 | |||

| 25 | 147.90582 | 44.06788 | 5 | 7.9192 | 32.9331 | 129.2 | 5.05 ± 0.51 | 0.042 ± 0.010 | 0.77 ± 0.12 | 0.262 ± 0.038 | 9.4139 |

| 15 | 5.1283 | 32.9665 | 152.3 | 4.90 ± 0.49 | 0.060 ± 0.011 | 0.87 ± 0.11 | 0.193 ± 0.034 | 16.5764 | |||

| 40 | 2.5627 | 33.0838 | 21.08 | 1.82 ± 0.18 | 0.065 ± 0.010 | 1.08 ± 0.11 | 0.062 ± 0.012 | 16.1874 | |||

| 31 | 148.00939 | 40.00293 | 5 | 20.2482 | 34.4823 | 8.66 | 4.70 ± 0.47 | 0.262 ± 0.026 | 1.88 ± 0.23 | 0.144 ± 0.027 | 4.4625 |

| 20 | 16.6783 | 34.2747 | 20.23 | 5.21 ± 0.52 | 0.383 ± 0.038 | 1.17 ± 0.18 | 0.702 ± 0.070 | 17.7603 | |||

| 36 | 148.01845 | 37.10271 | 5 | 19.5928 | 33.8659 | 2.66 | 2.20 ± 0.22 | 0.056 ± 0.010 | 1.73 ± 0.17 | 0.108 ± 0.016 | 3.7826 |

| 33 | 17.3377 | 34.2599 | 19.44 | 2.71 ± 0.27 | 0.048 ± 0.011 | 2.32 ± 0.23 | 0.093 ± 0.010 | 13.2455 | |||

| 40 | 14.9937 | 34.0616 | 33.48 | 2.60 ± 0.26 | 0.064 ± 0.012 | 2.34 ± 0.23 | 0.081 ± 0.010 | 13.0464 | |||

| 46 | 145.89192 | 34.05742 | 5 | 23.5155 | 34.4775 | 6.44 | 4.31 ± 0.43 | 0.947 ± 0.095 | 1.17 ± 0.13 | 0.575 ± 0.058 | 12.2051 |

| 61 | 149.77839 | 36.66245 | 5 | 24.6333 | 34.4700 | 1.33 | 5.19 ± 0.52 | 1.234 ± 0.123 | 1.02 ± 0.14 | 0.417 ± 0.052 | 5.8806 |

| 20 | 24.1555 | 34.4602 | 2.14 | 4.94 ± 0.49 | 0.562 ± 0.056 | 2.28 ± 0.23 | 0.334 ± 0.038 | 12.7721 | |||

| 68 | 149.53298 | 38.82417 | 5 | 21.7025 | 34.6008 | 2.03 | 5.55 ± 0.56 | 1.204 ± 0.120 | 2.13 ± 0.21 | 0.448 ± 0.048 | 10.4037 |

| 20 | 21.3631 | 34.5912 | 2.57 | 5.49 ± 0.55 | 0.757 ± 0.076 | 2.05 ± 0.21 | 0.482 ± 0.050 | 14.7758 | |||

| 81 | 148.79276 | 43.08188 | 5 | 16.5603 | 34.0160 | 23.22 | 4.76 ± 0.48 | 0.154 ± 0.020 | 0.94 ± 0.13 | 0.340 ± 0.039 | 11.0367 |

| 20 | 13.0126 | 34.0546 | 77.54 | 4.82 ± 0.48 | 0.087 ± 0.012 | 1.29 ± 0.14 | 0.125 ± 0.018 | 15.0450 | |||

| 87 | 149.89904 | 43.87579 | 5 | 4.7375 | 33.0093 | 161.57 | 3.08 ± 0.31 | 1.112 ± 0.111 | 0.90 ± 0.16 | 0.487 ± 0.050 | 16.5432 |

| 88 | 149.87744 | 44.96065 | 5 | 3.5710 | 33.0190 | 21.31 | 2.02 ± 0.20 | 0.318 ± 0.032 | 1.08 ± 0.16 | 0.239 ± 0.034 | 10.7690 |

| 15 | 3.5203 | 33.0196 | 68.20 | 3.92 ± 0.39 | 0.066 ± 0.010 | 0.88 ± 0.12 | 0.144 ± 0.021 | 14.0514 | |||

| Station No. | Coordinates | Depth (m) | CSPM (mg/L) | (Bq/(m2·day)) | FSPM (g/(m2·day)) | CPOC (mg/L) | FPOC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lat. (N) | Long. (E) | (mg C/(m2·Day)) | (mmol C/(m2·Day)) | ||||||

| 1 | 136.74049 | 42.88050 | 5 | 10.8264 | 0.9138 | 39.92 | 0.061 | 191.25 | 15.92 |

| 27 | 18.9233 | 0.075 | |||||||

| 40 | 18.2654 | 0.095 | |||||||

| 6 | 143.76805 | 51.36921 | 5 | 7.4075 | 0.4235 | 30.93 | 0.183 | 428.07 | 35.60 |

| 20 | 12.8219 | 0.097 | |||||||

| 21 * | 145.51447 | 46.84548 | 5 | 19.9269 | – | – | 0.160 | – | – |

| 22 | 145.98249 | 45.98332 | 5 | 4.5184 | 0.8682 | 56.59 | 0.085 | 513.01 | 42.71 |

| 20 | 11.9668 | 0.146 | |||||||

| 40 | 11.1527 | 0.020 | |||||||

| 23 | 146.48012 | 45.06959 | 5 | 10.1514 | 0.6133 | 28.06 | 0.080 | 166.20 | 13.84 |

| 30 | 13.6434 | 0.061 | |||||||

| 25 | 147.90582 | 44.06788 | 5 | 9.4139 | 0.5928 | 48.36 | 0.103 | 536.60 | 44.68 |

| 15 | 16.5764 | 0.198 | |||||||

| 40 | 16.1874 | 0.167 | |||||||

| 31 | 148.00939 | 40.00293 | 5 | 4.4625 | 0.3245 | 8.52 | 0.062 | 49.09 | 4.09 |

| 20 | 17.7603 | 0.066 | |||||||

| 36 | 148.01845 | 37.10271 | 5 | 3.7826 | 0.0744 | 7.94 | 0.064 | 53.33 | 4.44 |

| 33 | 13.2455 | 0.075 | |||||||

| 40 | 13.0464 | 0.063 | |||||||

| 46 * | 145.89192 | 34.05742 | 5 | 12.2051 | – | – | 0.088 | – | – |

| 61 | 149.77839 | 36.66245 | 5 | 5.8806 | 0.4217 | 10.47 | 0.048 | 65.13 | 5.42 |

| 20 | 12.7721 | 0.068 | |||||||

| 68 | 149.53298 | 38.82417 | 5 | 10.4037 | 0.4019 | 10.88 | 0.028 | 46.24 | 3.85 |

| 20 | 14.7758 | 0.079 | |||||||

| 81 | 148.79276 | 43.08188 | 5 | 11.0367 | 0.3595 | 20.16 | 0.028 | 82.73 | 6.89 |

| 20 | 15.0450 | 0.079 | |||||||

| 87 * | 149.89904 | 43.87579 | 5 | 16.5432 | – | – | 0.119 | – | – |

| 88 | 149.87744 | 44.96065 | 5 | 10.7690 | 0.1255 | 8.13 | 0.117 | 74.38 | 6.19 |

| 15 | 14.0514 | 0.110 | |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bezhin, N.A.; Tokar’, E.A.; Tarasevich, D.V.; Razina, V.A.; Matskevich, A.I.; Turyanskiy, V.A.; Shibetskaia, I.G.; Patrushev, D.K. Distribution of 210Pb and 210Po and Particulate Organic Carbon (POC) Fluxes in the Northwestern Pacific Ocean in Summer 2024. Water 2026, 18, 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010031

Bezhin NA, Tokar’ EA, Tarasevich DV, Razina VA, Matskevich AI, Turyanskiy VA, Shibetskaia IG, Patrushev DK. Distribution of 210Pb and 210Po and Particulate Organic Carbon (POC) Fluxes in the Northwestern Pacific Ocean in Summer 2024. Water. 2026; 18(1):31. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010031

Chicago/Turabian StyleBezhin, Nikolay A., Eduard A. Tokar’, Diana V. Tarasevich, Viktoriia A. Razina, Anna I. Matskevich, Vladislav A. Turyanskiy, Iuliia G. Shibetskaia, and Dmitry K. Patrushev. 2026. "Distribution of 210Pb and 210Po and Particulate Organic Carbon (POC) Fluxes in the Northwestern Pacific Ocean in Summer 2024" Water 18, no. 1: 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010031

APA StyleBezhin, N. A., Tokar’, E. A., Tarasevich, D. V., Razina, V. A., Matskevich, A. I., Turyanskiy, V. A., Shibetskaia, I. G., & Patrushev, D. K. (2026). Distribution of 210Pb and 210Po and Particulate Organic Carbon (POC) Fluxes in the Northwestern Pacific Ocean in Summer 2024. Water, 18(1), 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010031