Assessing the Impact of Land Use and Landscape Patterns on Water Quality in Yilong Lake Basin (1993–2023)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

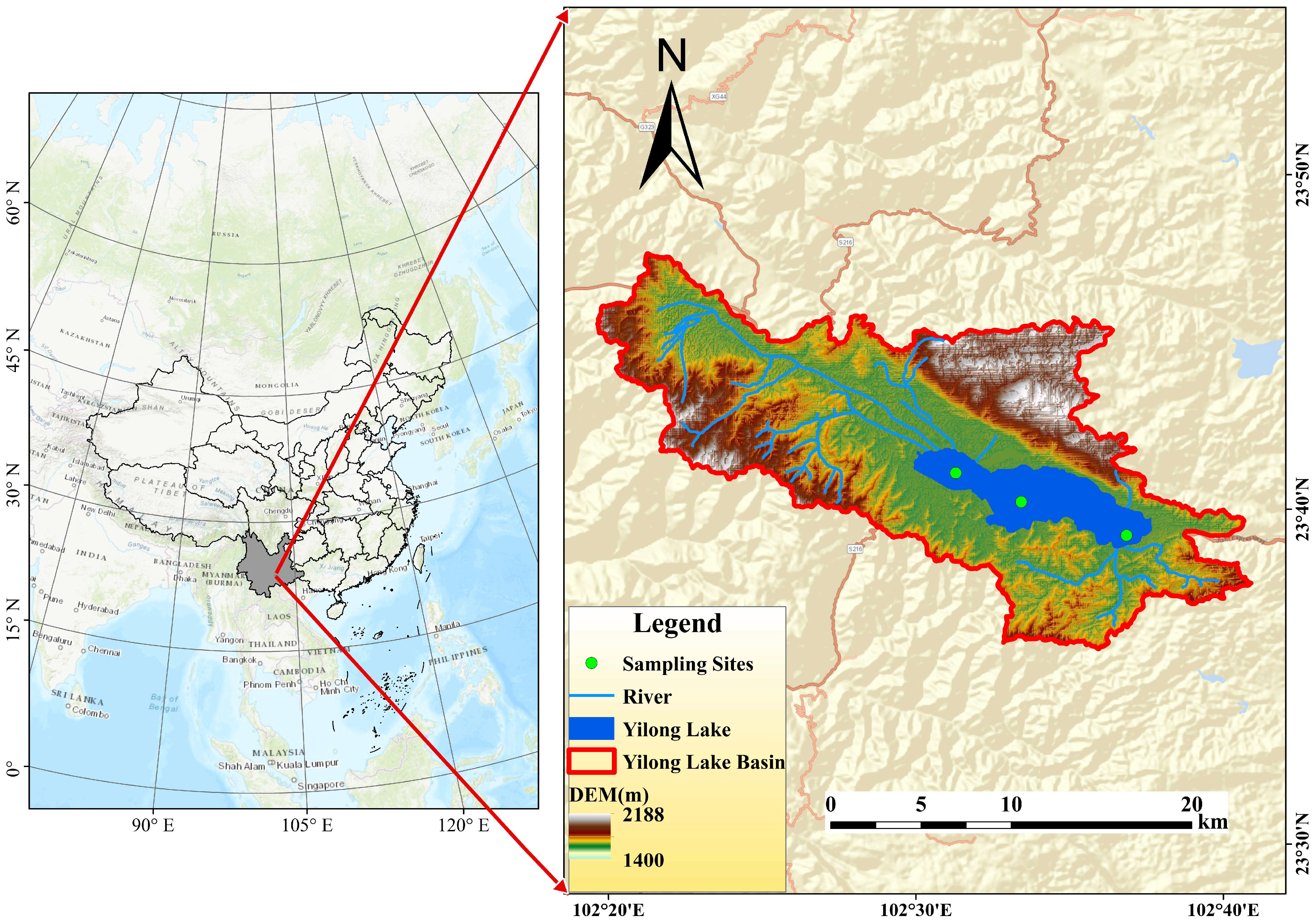

2.1. Research Area

2.2. Spatial Data

2.3. Water Quality Data

2.4. Research Methods

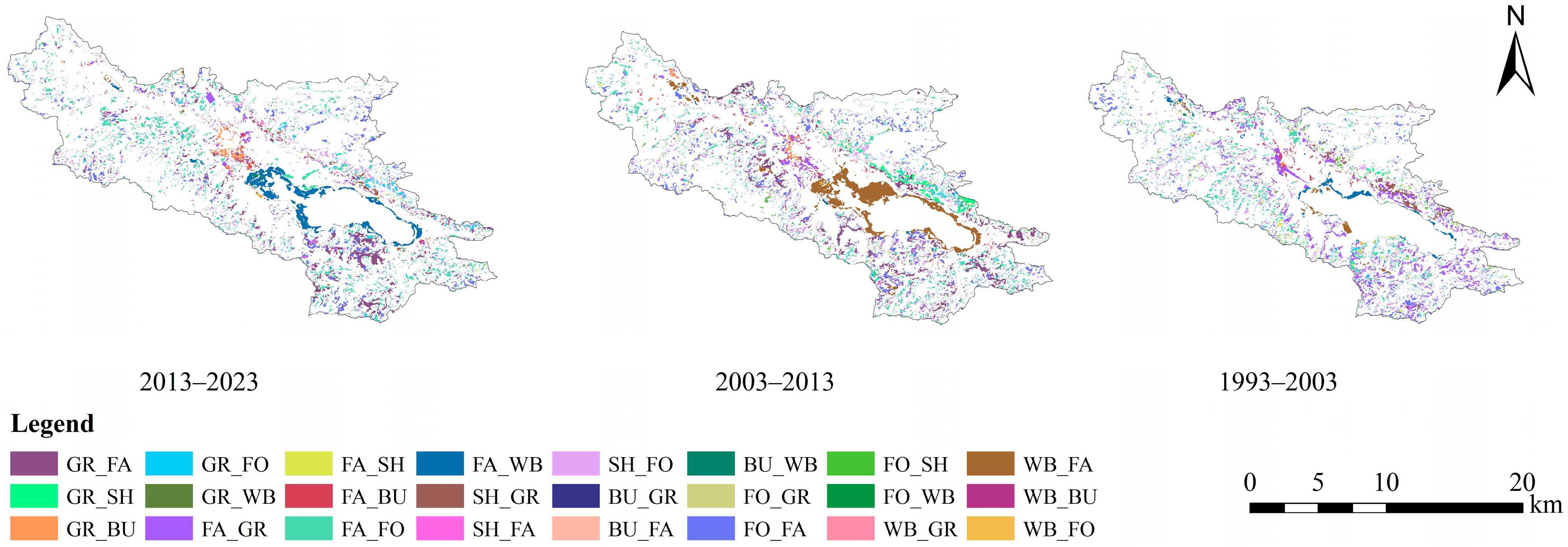

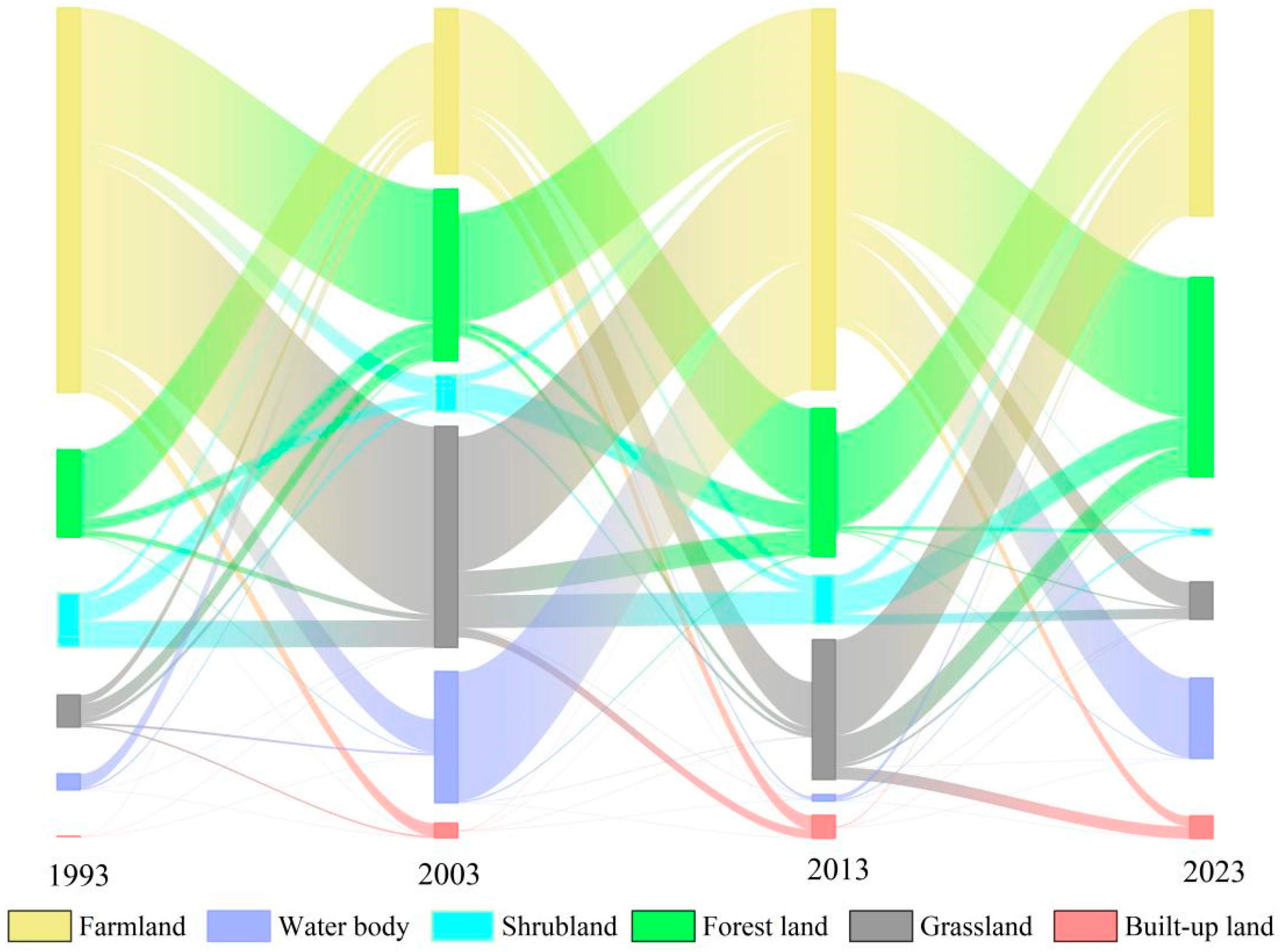

2.4.1. Land Use Transfer Matrix

2.4.2. Landscape Pattern Indices

2.4.3. Redundancy Analysis (RDA)

3. Results

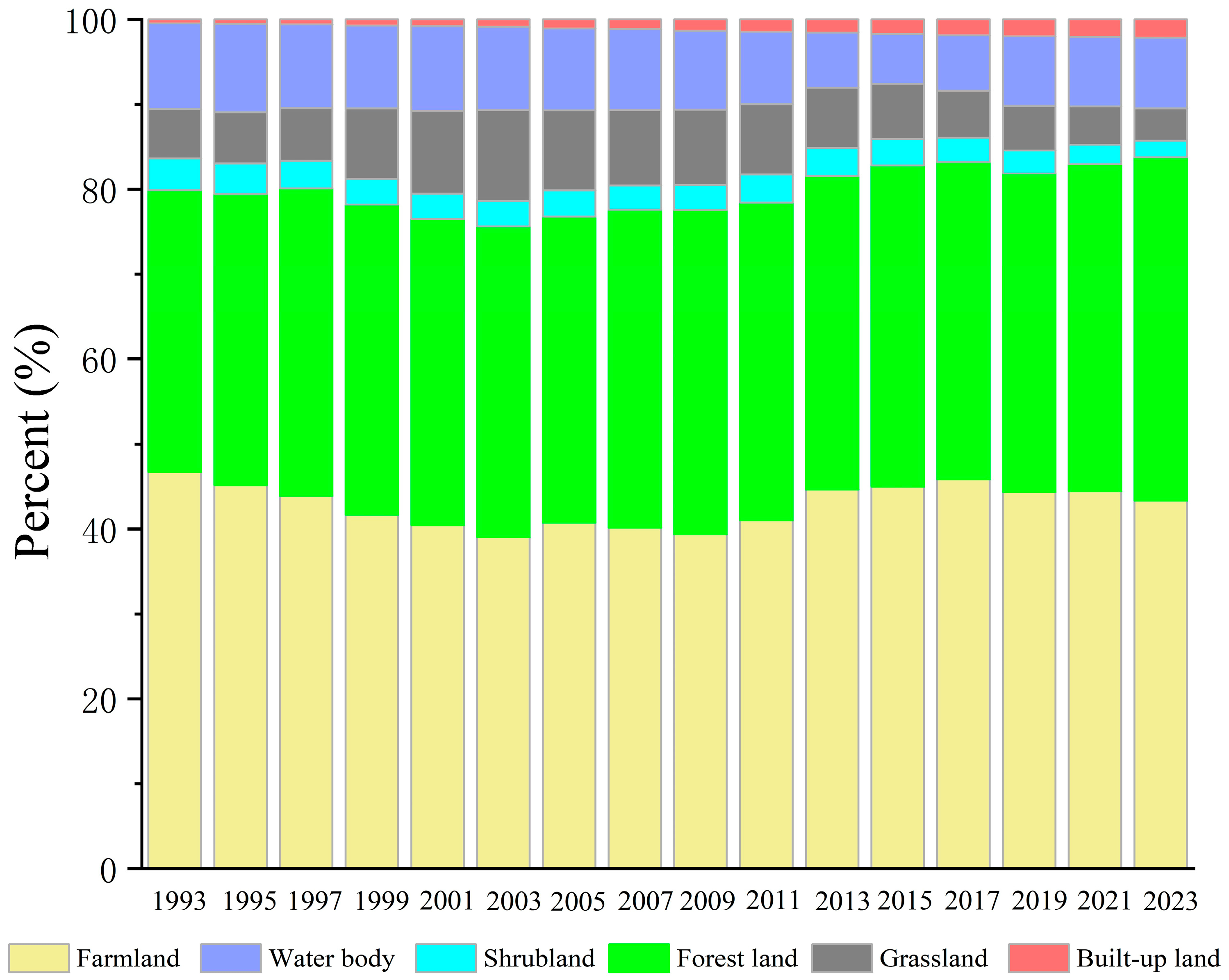

3.1. Land Use Change

3.2. Water Quality Change

3.3. Redundancy Analysis (RDA) of Landscape Pattern and Water Quality of Yilong Lake Basin from 1993 to 2023

4. Discussion

4.1. Reasons for Water Quality Changes

4.2. Influence of Landscape Pattern Indices on Water Quality

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- From 1993 to 2023, land use in the Yilong Lake Basin changed notably: farmland, shrubland, grassland, and water areas decreased, while forest land and built-up land expanded, especially the latter. The patch density slightly declined, but the landscape connectivity and heterogeneity improved. The water quality also changed, where TN, TP, Chl-a, and NH4+-N decreased overall, DO increased, and IMn and BOD5 showed opposite trends. These shifts suggest that eutrophication was mitigated, and the land use change had complex impacts on water quality.

- (2)

- Landscape patterns strongly influenced the water quality. The RDA showed that the LPI, ED, and LSI were positively correlated with IMn and negatively with TN, TP, NH4+-N, and Chl-a. The PD showed similar trends but was negatively correlated with DO and positively with BOD5. In contrast, CONTAG was positively correlated with most indices and negatively with BOD5. These results indicate that enhancing ecological connectivity may improve the water quality, while a higher patch density and heterogeneity may worsen it.

- (3)

- Over the past 30 years, ecological management reduced TN, TP, NH4+-N, Chl-a, IMn, and BOD5, but increased DO. Yet, urbanization still affected the water quality. Built-up land expanded rapidly, which increased the patch density; the loss of shrubland and grassland weakened filtration, which raised the runoff risks. The forest land expansion helped, but urban growth added new pollution sources. As most forests lie far from the lake, their purification role is limited. In general, the improvement of water quality in the Yilong Lake Basin was due to the reduction in farmland and the increase in forest lands, but the expansion of built-up land may pose a threat to water quality.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vörösmarty, C.J.; McIntyre, P.B.; Gessner, M.O.; Dudgeon, D.; Prusevich, A.; Green, P.; Glidden, S.; Bunn, S.E.; Sullivan, C.A.; Liermann, C.R.; et al. Global threats to human water security and river biodiversity. Nature 2010, 467, 555–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, S.B.; Saphores, J.D.; Feldman, D.L.; Hamilton, A.J.; Fletcher, T.D.; Cook, P.L.M.; Stewardson, M.; Sanders, B.F.; Levin, L.A.; Ambrose, R.F.; et al. Taking the “waste” out of “wastewater” for human water security and ecosystem sustainability. Science 2012, 337, 681–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Chen, Y.; Gozlan, R.E.; Liu, H.; Lu, Y.; Qu, X.; Xia, W.; Xiong, F.; Xie, S.; Wang, L. Patterns of fish communities and water quality in impounded lakes of China’s south-to-north water diversion project. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 713, 136515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purvis, L.; Dinar, A. Are intra- and inter-basin water transfers a sustainable policy intervention for addressing water scarcity? Water Secur. 2019, 9, 100058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodell, M.; Famiglietti, J.S.; Wiese, D.N.; Reager, J.T.; Beaudoing, H.K.; Landerer, F.W.; Lo, M.H. Emerging trends in global freshwater availability. Nature 2018, 557, 651–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinha, P.; Rollason, E.; Bracken, L.J.; Wainwright, J.; Reaney, S.M. A new framework for integrated, holistic, and transparent evaluation of inter-basin water transfer schemes. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 721, 137646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, Z.; Zheng, H.; Ouyang, Z.Y. Research progress on the relationship between biodiversity and ecosystem services. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2020, 31, 340–348. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Z.; Wu, D.; Niu, L.; Ma, X.; Li, Y.; Hillman, A.L.; Abbott, M.B.; Zhou, A. Contrasting ecosystem responses to climatic events and human activity revealed by a sedimentary record from lake Yilong, southwestern China. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 783, 146922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Meng, C.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Wu, J. Multi-spatial scale effects of multidimensional landscape pattern on stream water nitrogen pollution in a subtropical agricultural watershed. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 321, 115962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karr, J.R.; Schlosser, I.J. Water Resources and the Land-Water Interface: Water resources in agricultural watersheds can be improved by effective multidisciplinary planning. Science 1978, 201, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orwin, J.F.; Klotz, F.; Taube, N.; Kerr, J.G.; Laceby, J.P. Linking catchment structural units (CSUs) with water quality: Implications for ambient monitoring network design and data interpretation. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 312, 114881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basnyat, P.; Teeter, L.D.; Flynn, K.M.; Lockaby, B.G. Relationships between landscape characteristics and nonpoint source pollution inputs to coastal estuaries. Environ. Manag. 1999, 23, 539–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlosser, I.J.; Karr, J.R. Riparian vegetation and channel morphology impact on spatial patterns of water quality in agricultural watersheds. Environ. Manag. 1981, 5, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clément, F.; Ruiz, J.; Rodríguez, M.A.; Blais, D.; Campeau, S. Landscape diversity and forest edge density regulate stream water quality in agricultural catchments. Ecol. Indic. 2017, 72, 627–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Hou, X.; Li, W.; Aini, G.; Chen, L.; Gong, Y. Impact of landscape pattern at multiple spatial scales on water quality: A case study in a typical urbanised watershed in China. Ecol. Indic. 2015, 48, 417–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Lu, J. Spatial scale effects of landscape metrics on stream water quality and their seasonal changes. Water Res. 2021, 191, 116811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Gao, J.; Xie, Z.; Zhao, M.; Wang, E. Evaluating landscape ecological sensitivity of an estuarine island based on landscape pattern across temporal and spatial scales. Ecol. Indic. 2019, 101, 221–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Shen, Z.; Chen, L. Assessing how spatial variations of land use pattern affect water quality across a typical urbanized watershed in Beijing, China. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 176, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.W.; Hwang, S.J.; Lee, S.B.; Hwang, H.S.; Sung, H.C. Landscape ecological approach to the relationships of land use patterns in watersheds to water quality characteristics. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2009, 92, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, H.; Meng, W.; Zhang, Y.; Wan, J. Relationships between land use patterns and water quality in the Taizi river basin, China. Ecol. Indic. 2014, 41, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Song, J.; Yan, J. Influences of landscape pattern on water quality at multiple scales in an agricultural basin of western China. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 319, 120986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uuemaa, E.; Roosaare, J.; Mander, Ü. Scale dependence of landscape metrics and their indicatory value for nutrient and organic matter losses from catchments. Ecol. Indic. 2005, 5, 350–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, C.P.; Bode, R.W.; Smith, A.J.; Kleppel, G.S. Land-use proximity as a basis for assessing stream water quality in New York state (USA). Ecol. Indic. 2010, 10, 727–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, S.L.; Hayes, D.B.; Kendall, A.D.; Hyndman, D.W. The land-use legacy effect: Towards a mechanistic understanding of time-lagged water quality responses to land use/cover. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 579, 1794–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.; Xu, Q.; Yi, H.; Jin, L. Study on the threshold relationship between landscape pattern and water quality considering spatial scale effect—A case study of dianchi lake basin in China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 44103–44118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, L.; Yu, Y.; Shen, Z. Water quality variability affected by landscape patterns and the associated temporal observation scales in the rapidly urbanizing watershed. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 298, 113523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Xiong, X.; Wang, K.; Li, X.; Hu, H.; Li, Q.; Yin, H.; Wu, C. The effects of land use on water quality of alpine rivers: A case study in Qilian mountain, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 875, 162696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, W.; Yang, N.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, Z. Impacts of land use patterns on river water quality: The case of Dongjiang Lake Basin, China. Ecol. Inform. 2023, 75, 102083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Li, Y.; Zou, R.; He, B.; Zhu, X.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhu, Y. A three-dimensional water quality modeling approach for exploring the eutrophication responses to load reduction scenarios in lake Yilong (China). Environ. Pollut. 2013, 177, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Ma, R.; Shi, H.; Li, J.; Tu, S. Centennial lake environmental evolution reflected by diatoms in Yilong lake, Yunnan province, China. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 5288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Yu, Z.; Luo, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, L.; Zhou, X. Spatial and temporal variations in the relationship between lake water surface temperatures and water quality—A case study of Dianchi Lake. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 624, 859–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, K.; Pan, M.; Luo, Y.; Chen, K.; Zhao, Y.; Zhou, X. A time-series analysis of urbanization-induced impervious surface area extent in the Dianchi lake watershed from 1988–2017. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2018, 40, 573–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Chen, Z.; Mao, G.; Chen, L.; Crittenden, J.; Li, R.Y.M.; Chai, L. Evaluation of eutrophication in freshwater lakes: A new non-equilibrium statistical approach. Ecol. Indic. 2019, 102, 686–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Wang, M.; Liang, Z.; Zhou, Q. Identification of regime shifts and their potential drivers in the shallow eutrophic lake Yilong, southwest China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Cui, B.; Chen, B.; Zhang, K.; Wei, D.; Gao, H.; Xiao, R. Spatial distribution and ecological risk assessment of heavy metals in surface sediments from a typical plateau lake wetland, China. Ecol. Model. 2011, 222, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Tan, B.; Ni, J.; Liao, M.N. Hydroclimate changes since last glacial maximum: Geochemical evidence from Yilong lake, southwestern China. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2018, 38, 8973–8982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Yang, Z.; Cui, B.; Gao, H.; Ding, Q. Some heavy metals distribution in wetland soils under different land use types along a typical plateau lake, China. Soil Tillage Res. 2010, 106, 344–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 3838-2002; Environmental Quality Standard for Surface Water. State Environmental Protection Administration of China: Beijing, China, 2002.

- U.S. Geological Survey. Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) 1 Arc-Second Digital Terrain Elevation Data—Void Filled. U.S. Geological Survey. 2018. Available online: https://www.usgs.gov/centers/eros/science/usgs-eros-archive-digital-elevation-shuttle-radar-topography-mission-srtm-1 (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Yang, J. The 30 m Annual Land Cover Datasets and Its Dynamics in China from 1985 to 2023. Zenodo. 2024. Available online: https://www.ncdc.ac.cn/portal (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Meals, D.W.; Dressing, S.A.; Davenport, T.E. Lag time in water quality response to best management practices: A review. J. Environ. Qual. 2009, 39, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, J.; Li, W.; Li, Y. Evaluating the effectiveness of landscape metrics in quantifying spatial patterns. Ecol. Indic. 2010, 10, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Li, S. Scale relationship between landscape pattern and water quality in different pollution source areas: A case study of the Fuxian lake watershed, China. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 121, 107136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Ji, W. Relating landscape characteristics to non-point source pollution in mine waste-located watersheds using geospatial techniques. J. Environ. Manag. 2007, 82, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, J.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Hou, Z.; Liao, J.; Fu, L.; Peng, Q. Influences of the land use pattern on water quality in low-order streams of the Dongjiang River basin, China: A multi-scale analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 551–552, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legendre, P.; Oksanen, J.; ter Braak, C.J.F. Testing the significance of canonical axes in redundancy analysis. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2010, 2, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karydis, M. Eutrophication assessment of coastal waters based on indicators: A literature review. Global NEST J. 2013, 11, 373–390. [Google Scholar]

- Suresh, K.; Tang, T.; Van Vliet, M.T.H.; Bierkens, M.F.P.; Strokal, M.; Sorger-Domenigg, F.; Wada, Y. Recent advancement in water quality indicators for eutrophication in global freshwater lakes. Environ. Res. Lett. 2023, 18, 063004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davison, W. Iron and manganese in lakes. Earth Sci. Rev. 1993, 34, 119–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastviken, D.; Persson, L.; Odham, G.; Tranvik, L. Degradation of dissolved organic matter in oxic and anoxic lake water. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2004, 49, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, Q.; Duan, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, H. Seasonal water quality changes and the eutrophication of lake Yilong in southwest China. Water 2022, 14, 3385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collinge, S.K. Ecological consequences of habitat fragmentation: Implications for landscape architecture and planning. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1996, 36, 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heathwaite, A.L.; Griffiths, P.; Parkinson, R.J. Nitrogen and phosphorus in runoff from grassland with buffer strips following application of fertilizers and manures. Soil Use Manag. 1998, 14, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.J.; Menzel, R.G.; Rhoades, E.D.; Williams, J.R.; Eck, H.V. Nutrient and sediment discharge from southern plains grasslands. J. Range Manag. 1983, 36, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, C.; Foy, R. Environmental impacts of nitrogen and phosphorus cycling in grassland systems. Outlook Agric. 2001, 30, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longyang, Q. Assessing the effects of climate change on water quality of plateau deep-water lake-a study case of hongfeng lake. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 647, 1518–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Landscape Pattern Index | Calculation Model | Indexical Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| PD | Patch density: The larger the value, the more fragmented the landscape is. | |

| ED | Edge density: The larger the value, the more heterogeneous the landscape patches are and the more fragmented the landscape is. | |

| LSI | Landscape shape index: The larger the value, the more irregular the shape inside the landscape is and the more fragmented and discretized the landscape is. | |

| LPI | Large patch index: The larger the value, the greater the influence of the dominant landscape type in the region is. | |

| COHESION | Patch cohesion: The larger the value, the higher the spatial aggregation degree of the landscape is. | |

| CONTAG | ∗ 100 | Contagion index: The larger the value, the better the landscape connectedness is. |

| SHDI | Shannon’s diversity index: The larger the value, the stronger the landscape heterogeneity is. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Huang, Y.; Wang, R.; Li, J.; Jiang, Y. Assessing the Impact of Land Use and Landscape Patterns on Water Quality in Yilong Lake Basin (1993–2023). Water 2026, 18, 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010030

Huang Y, Wang R, Li J, Jiang Y. Assessing the Impact of Land Use and Landscape Patterns on Water Quality in Yilong Lake Basin (1993–2023). Water. 2026; 18(1):30. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010030

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Yue, Ronggui Wang, Jie Li, and Yuhan Jiang. 2026. "Assessing the Impact of Land Use and Landscape Patterns on Water Quality in Yilong Lake Basin (1993–2023)" Water 18, no. 1: 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010030

APA StyleHuang, Y., Wang, R., Li, J., & Jiang, Y. (2026). Assessing the Impact of Land Use and Landscape Patterns on Water Quality in Yilong Lake Basin (1993–2023). Water, 18(1), 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010030