Research on Water Hammer Protection in Coastal Drainage Pumping Stations Based on the Combined Application of Flap Valve and Sluice Gate

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

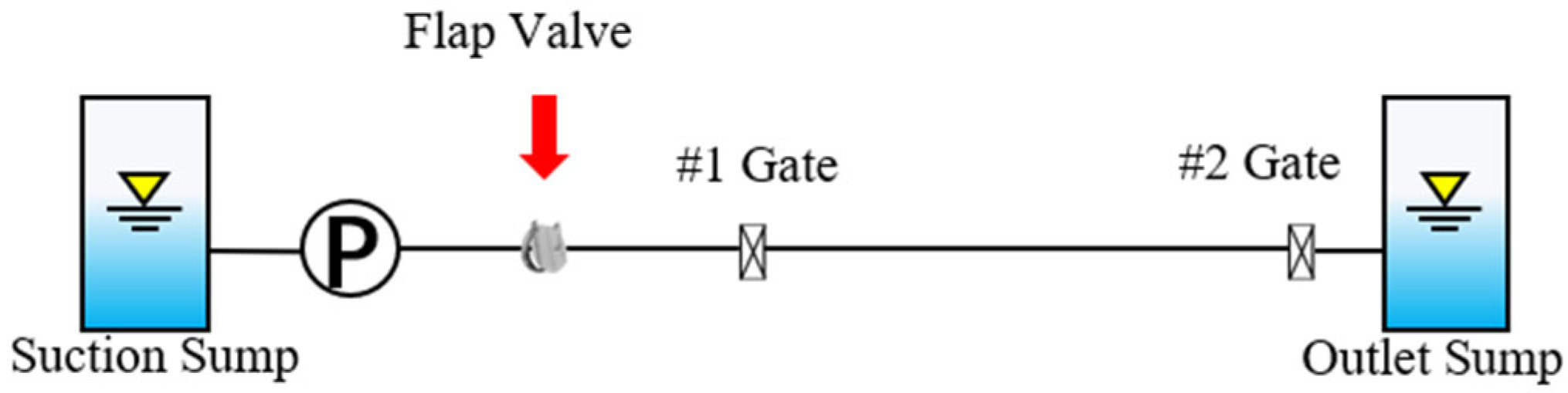

2.1. Coordinated Control Strategy and System Modeling

2.2. Mathematical Model for Pressurized Pipeline Calculations

2.2.1. Mathematical Model for Steady Flow Conditions in Pressurized Pipelines

- (1)

- Calculation of Frictional Head Loss

- (2)

- Calculation of local head loss

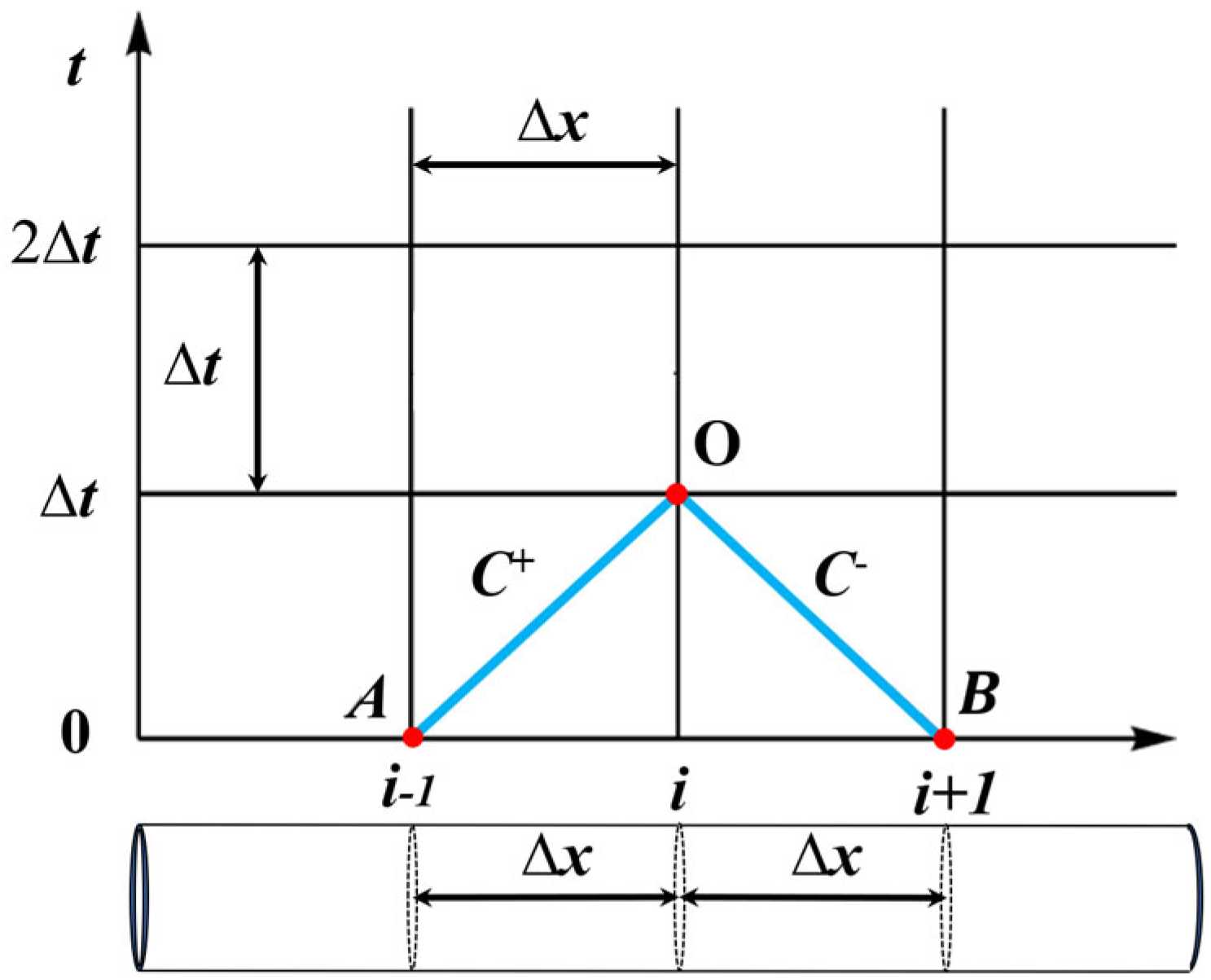

2.2.2. Mathematical Model for Water Hammer Calculation

2.3. Characteristic Equations for Water Hammer Calculation Nodes

2.3.1. Governing Equations for the Pump Node

- (1)

- Runner Boundary Head Equilibrium Equation

- (2)

- Treatment of Complete Characteristic Curves

- (3)

- Unit Driving Torque Equilibrium Equation

2.3.2. Flap Valve Node Governing Equations

2.3.3. Sluice Gate Control Node Equations

2.4. Numerical Model Validation

3. Practical Case

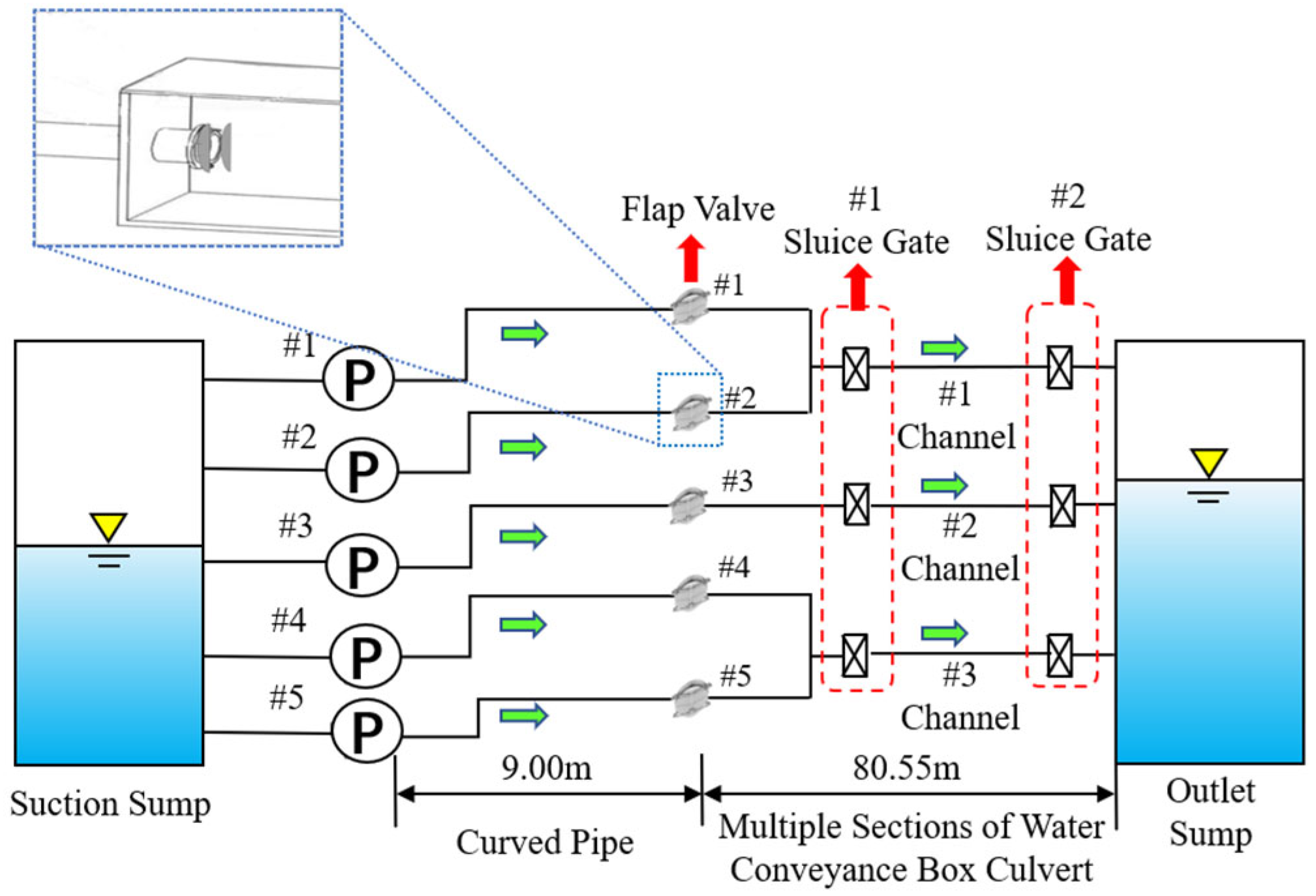

3.1. Project Overview

3.2. Control Settings

- (1)

- Starting Conditions for Drainage Pumping Station: When the water level in the suction sump exceeds the design level of 5.03 m, the pump units must be started immediately and maintained in continuous operation.

- (2)

- Water Hammer Control Conditions: Based on the engineering design requirements, during a pump-trip accident, the maximum reverse speed of the pumps must not exceed −150.00% of the rated speed, and the duration of this overspeed condition must not be greater than 120 s. Furthermore, the maximum pressure in the flow channel downstream of the pump outlets must not exceed 1.5 times the pump outlet pressure, and the minimum pressure must not fall below −4 m (water column).

- (3)

- Control Requirement for gates operation: Owing to the substantial self-weight of steel plate gates, the closing speed must be appropriately limited. According to the specification [29], the gates must be fully closed within 120 s. Excessively rapid closure of emergency gate in pumping stations can induce severe water hammer effects, accompanied by mechanical shocks and system negative pressure. These transient phenomena may cause damage to pipelines, pump units, and the gates themselves, potentially leading to cascading safety incidents.

3.3. Computational Cases

- (i)

- Only the flap valve close normally, with the sluice gates remaining open.

- (ii)

- The flap valve fails, and only the sluice gates operate. All sluice gates adopt a single-stage linear closure rule, with the control strategy schemes detailed in Table 4.

- (iii)

- Combined application of flap valves and sluice gates. The scenarios are shown in Table 5.

4. Results and Discussion

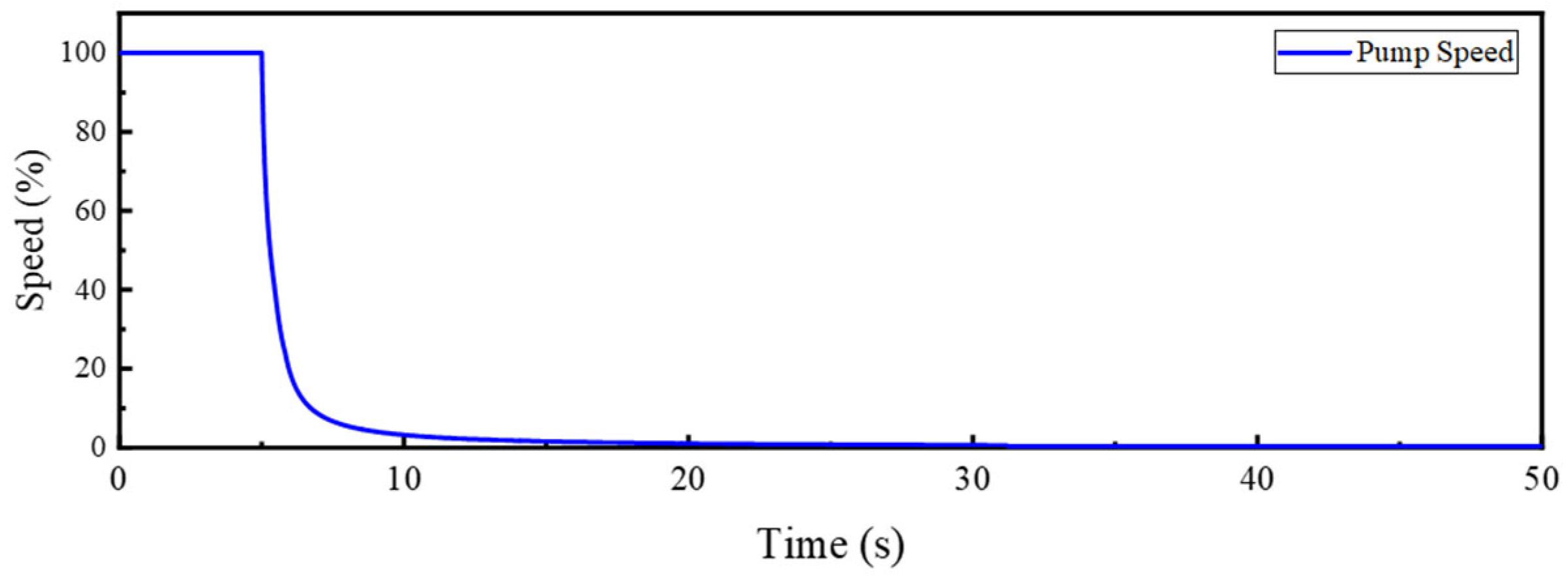

4.1. Analysis of the Hydraulic Transient Process Under Normal Flap Valve Operation

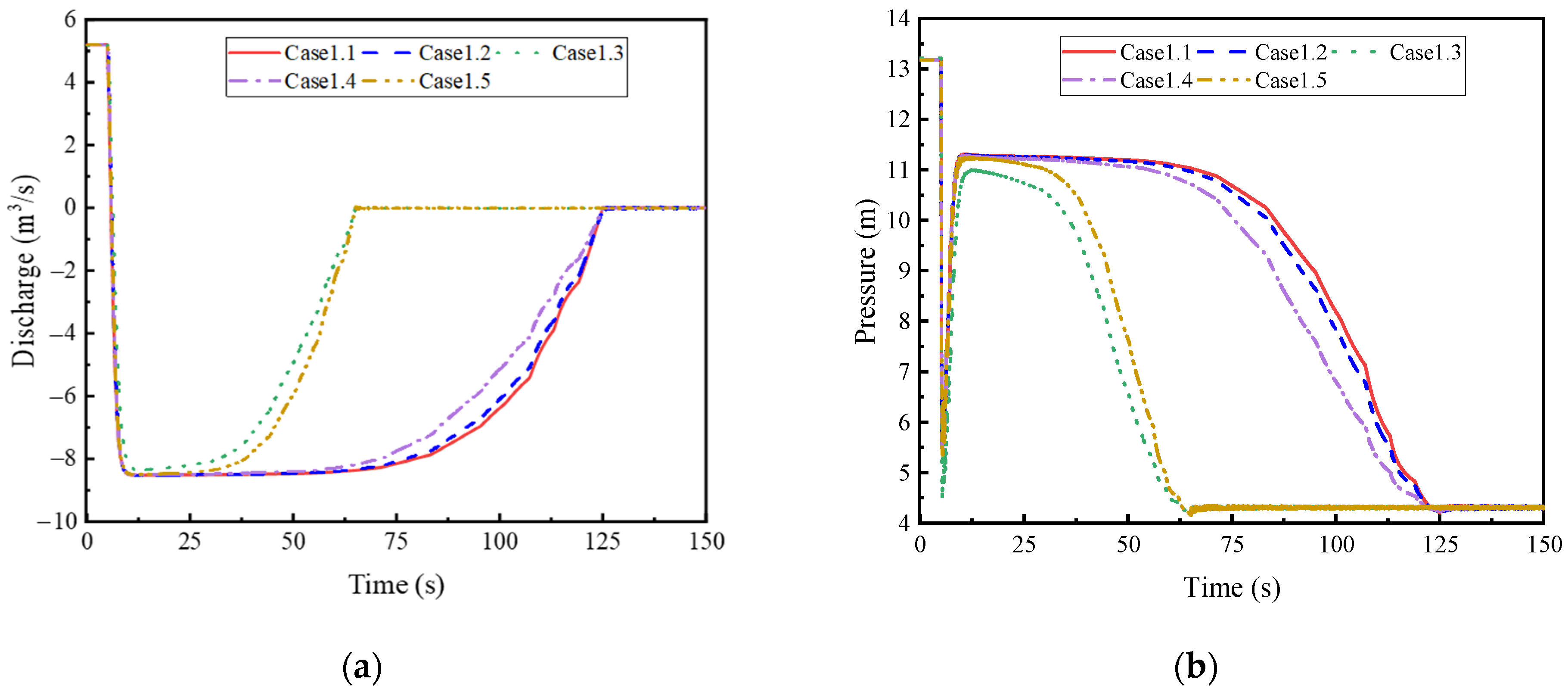

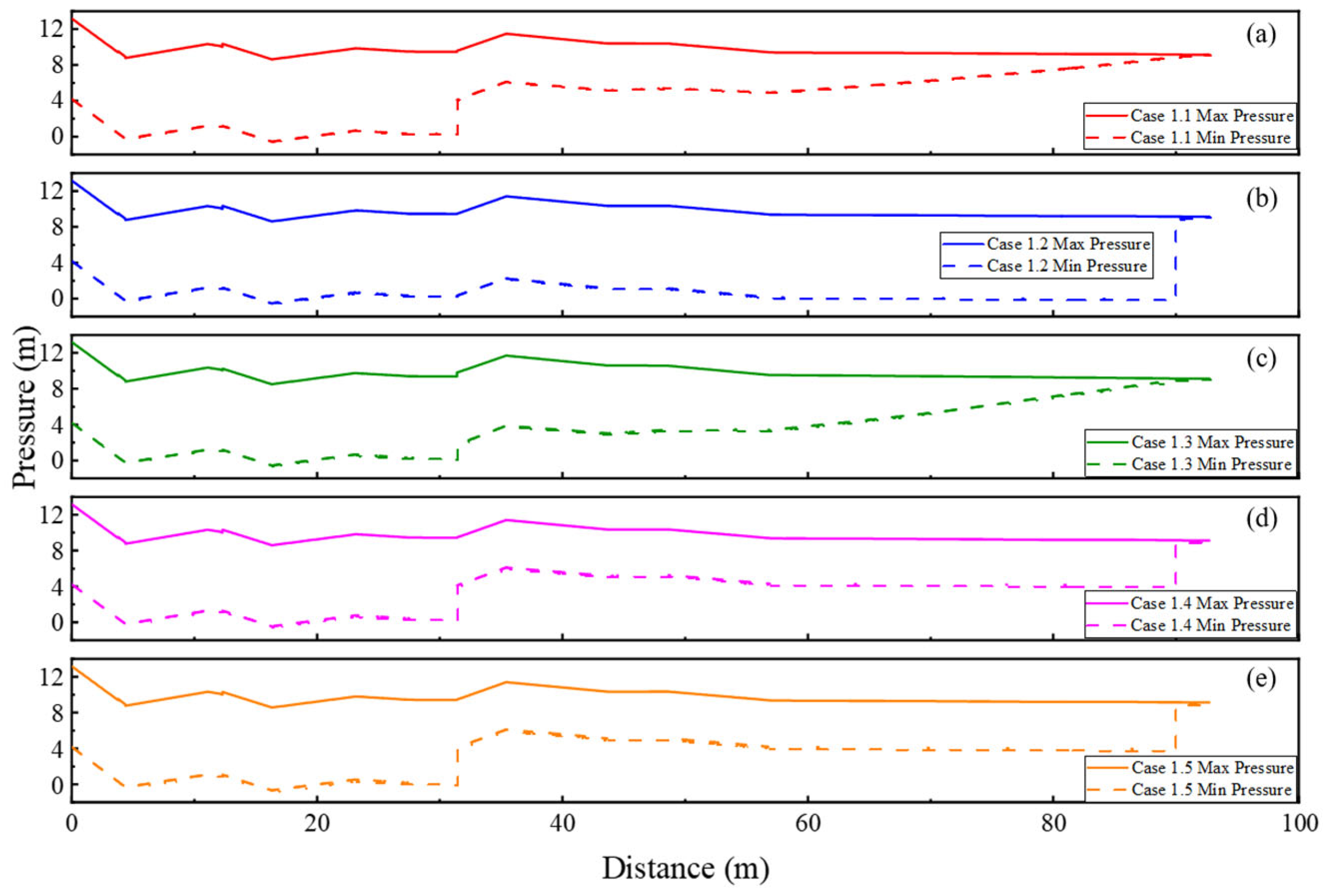

4.2. Analysis of the Hydraulic Transient Process When the Flap Valve Fails to Close

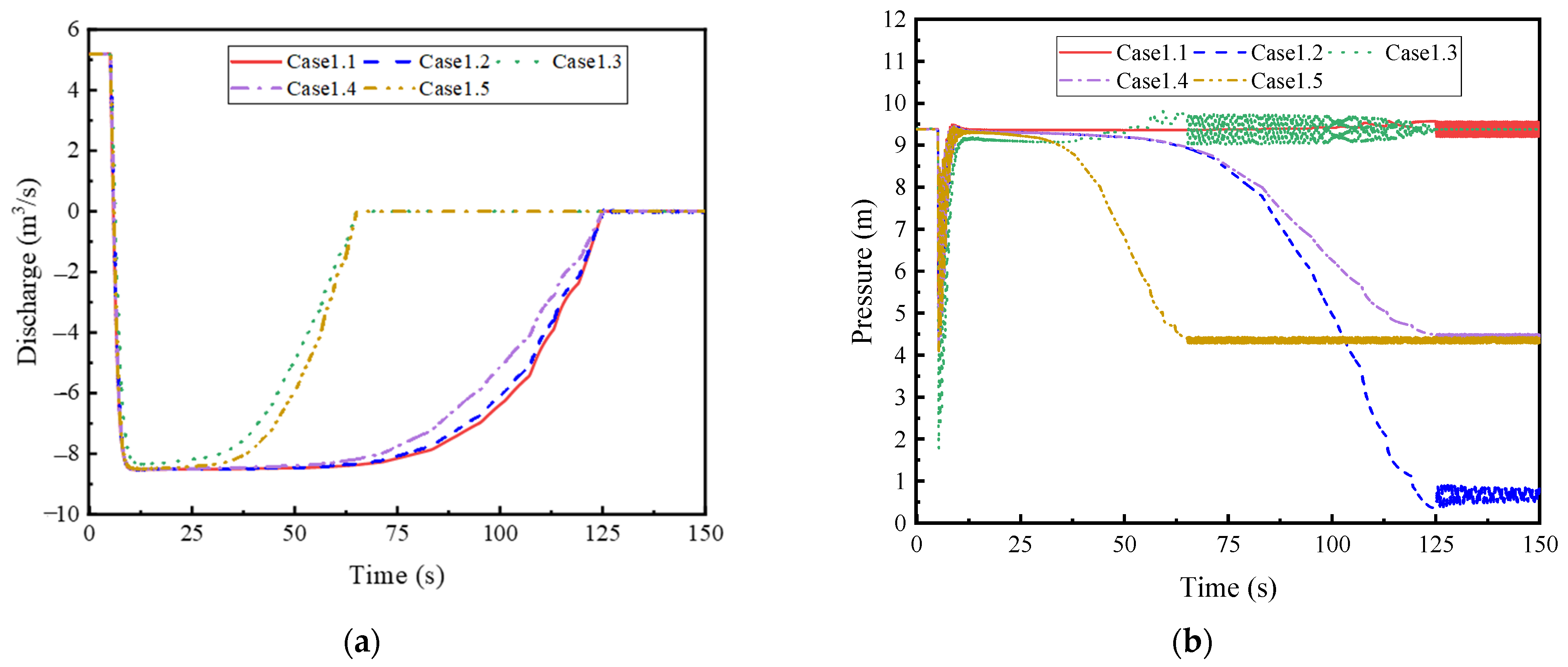

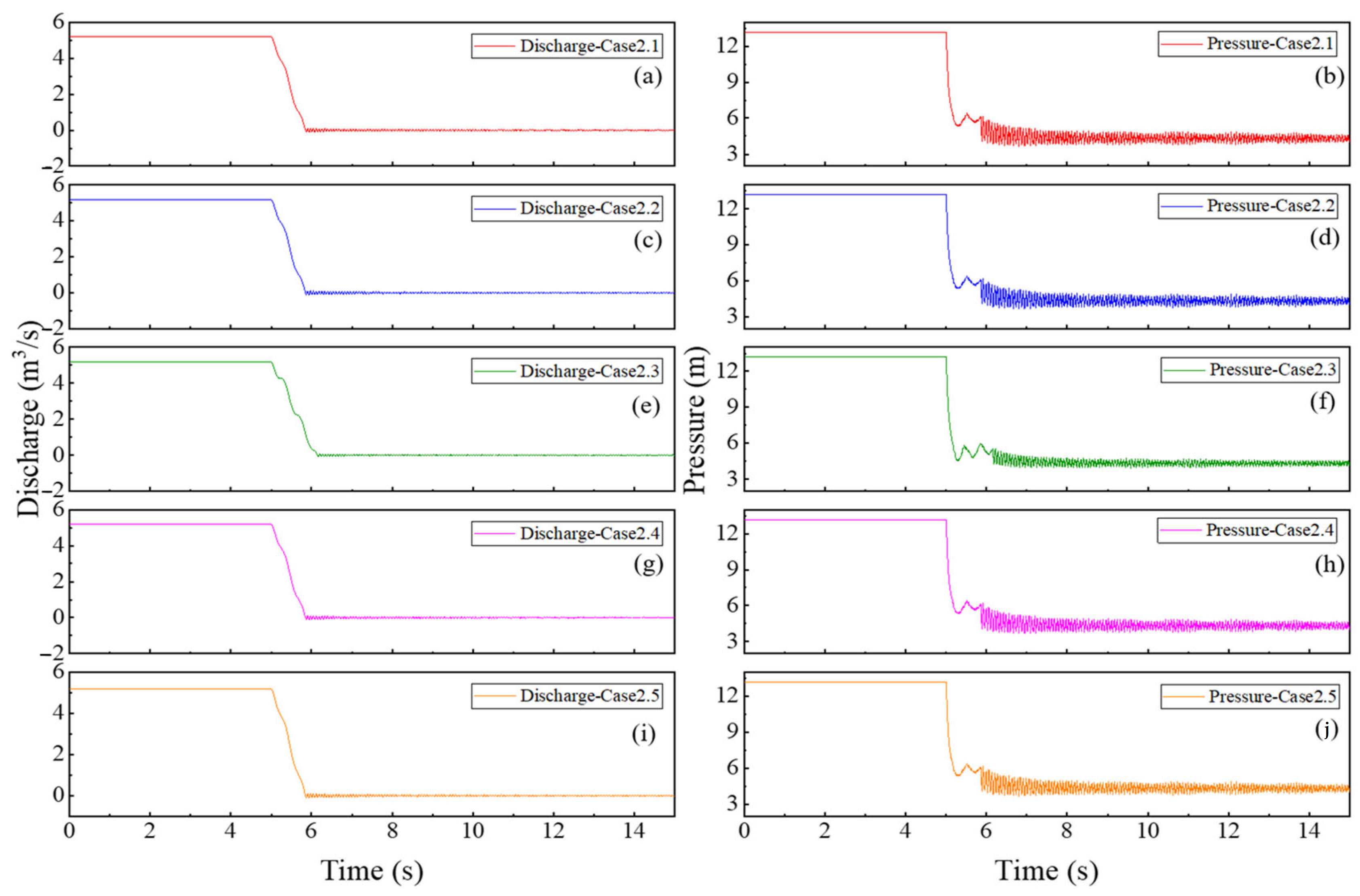

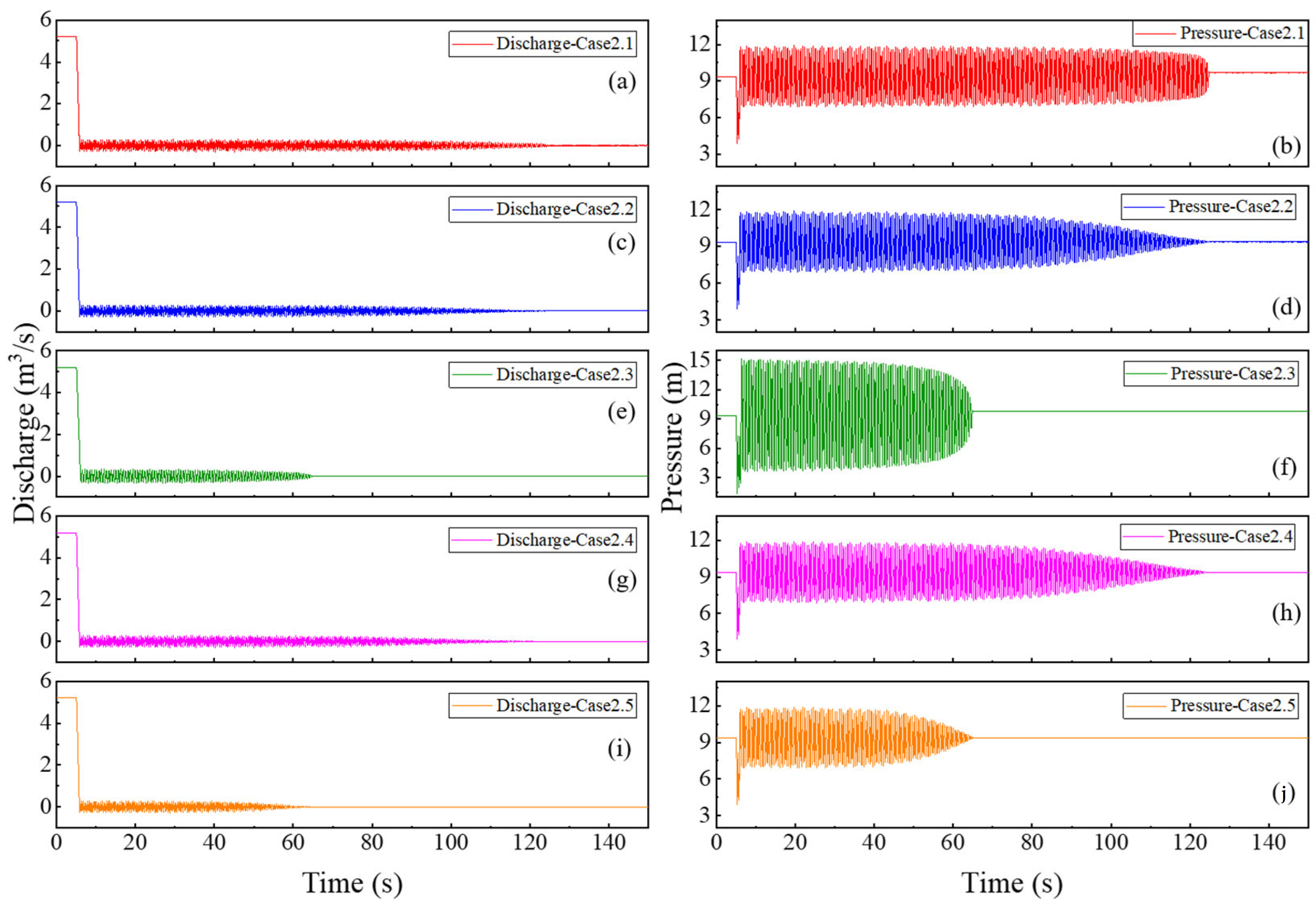

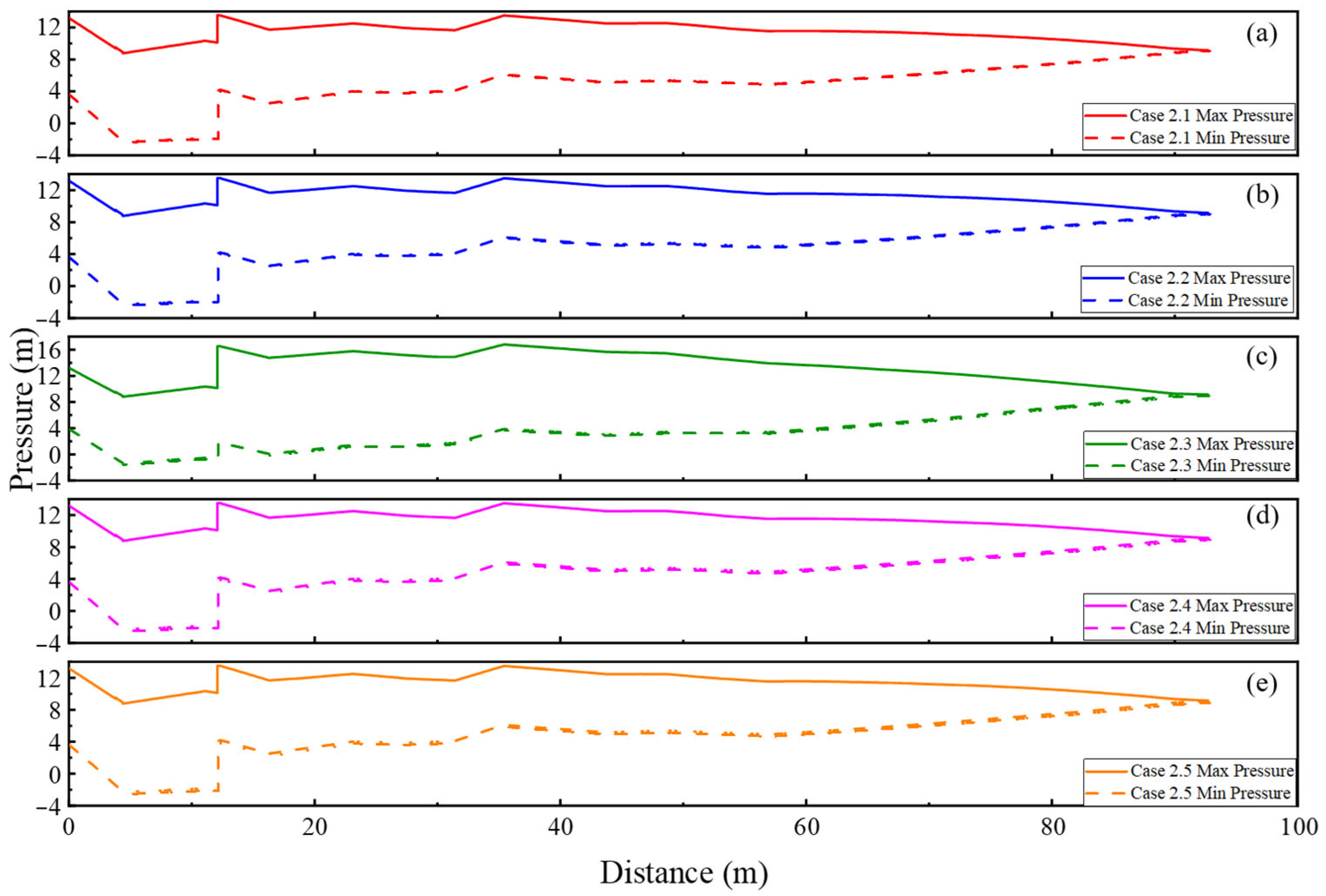

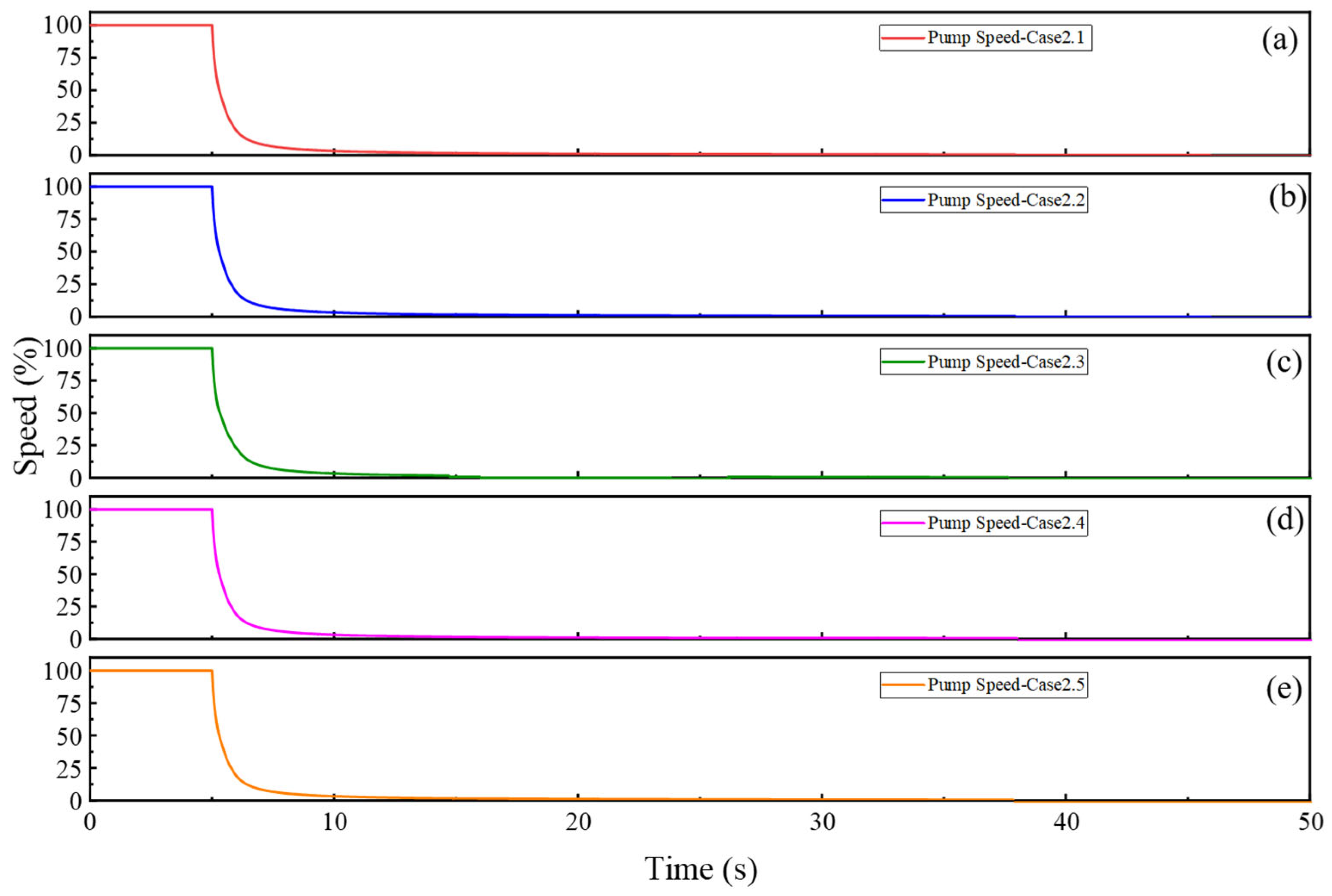

4.3. Analysis of the Hydraulic Transient Process Under Coordinated Application of the Flap Valve and Sluice Gates

5. Conclusions

- While normal flap valve closure effectively prevents backflow and pump reversal—with channel pressures (maximum: 13.53 m; minimum: −2.22 m) complying with basic safety standards (Section 3.2)—it induces persistent, high-amplitude pressure fluctuations downstream. These oscillations, resulting from water inertia in the elongated drainage channel, pose a potential long-term fatigue risk to the channel structure. Therefore, designs relying solely on flap valves must account for these cyclic loads.

- In the event of flap valve failure, slow single-gate closure strategies prove inadequate, allowing pump reversal speeds to approach −150% of the rated value. In contrast, rapid closure (60 s) of the upstream Gate #1 (Case 1.3) effectively limits the maximum reversal speed to −147.25%, halved the reversal duration to 60 s, and maintained all channel pressures within safe limits. Thus, a 60 s closure rule for the upstream sluice gate is recommended as the primary protection against flap valve failure.

- The combined use of flap valves and sluice gates delivers optimal performance. The flap valve ensures immediate backflow blocking, eliminating pump reversal, while the strategic closure of the sluice gates mitigates subsequent pressure fluctuations. Case 2.5 (simultaneous 60 s linear closure of both gates) demonstrates the highest efficacy, significantly damping oscillations and reducing the system stabilization time from a persistent state to 60 s. This scheme is therefore the preferred design solution, offering superior pressure stability, backflow control, and response speed.

- These conclusions are based on numerical simulations of a typical coastal drainage pumping station and require further validation through field tests or physical modeling. For practical applications, gate closure parameters should be optimized based on specific system characteristics. Future work should focus on: (1) developing real-time adaptive control strategies for sluice gates; (2) investigating the influence of key geometric parameters on transient performance; (3) exploring multi-stage closure rules to balance pressure surge and backflow control; and (4) experimentally verifying the synergistic mechanisms of combined protection.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sun, Y.-M.; Yu, G.-P.; Liu, C. Research on closing control of the sluice gate for sudden power off of large pump. Adv. Sci. Lett. 2011, 4, 2316–2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghidaoui, M.S.; Zhao, M.; McInnis, D.A.; Axworthy, D.H. A review of water hammer theory and practice. Appl. Mech. Rev. 2005, 58, 49–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Wang, L.; Cai, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Fan, X. The sealing performance and failure analysis of marine valve packing seal structures based on dimensionless function definition. Ocean Eng. 2025, 316, 119939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indimath, S.S.; Das, S.; Mukhopadyay, G.; Bhattacharyya, S. Prevention of in-service failure of seal valve axles of blast furnace through non-destructive condition monitoring. J. Fail. Anal. Prev. 2015, 15, 430–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, K.K.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, R.R. Systematic review of bearing component failure: Strategies for diagnosis and prognosis in rotating machinery. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2025, 50, 5353–5375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.; Liu, D.; Zheng, Y.; Chen, H. Review of research on the three-dimensional transition process of large-scale low-lift pump. Energies 2022, 15, 8338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supri, I.M.M.; Madon, R.H.; Salleh, Z.M.; Madon, H. Design and analysis of a new check valve on water hammer performance by using SolidWorks Flow Simulation. Prog. Eng. Appl. Technol. 2021, 2, 830–843. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, R.; Xiang, C.; Chen, Y.; Fang, H.; Wang, L. Analysis of flow capability of gate with small flap valve base on CFD. Hydropower Energy Sci. 2018, 36, 156–158. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Du, Y. Opening angle and impact force analysis of different types flap valve in pumping stations. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 371, 022067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, W.; Lu, W.; Wang, C.; Fu, G. Numerical and experimental study on the opening angle of the double-stage flap valves in pumping stations. Front. Energy Res. 2022, 10, 866044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Lou, H.; Li, J.; Xu, Y.; Ye, F.; Zhang, Y. Structure and impact force calculating of the laisses-aller side-turn-over flap valve of large diameter. J. Irrig. Drain. 2008, 4, 44–47. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lu, W. Studies on the Mechanical Characteristics of Flap Valve Cutoff Device in Pumping Stations. Ph.D. Thesis, Shanghai University, Shanghai, China, 2009. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Malmur, R. Methods of drainage and transfer of rainwater. E3S Web Conf. 2019, 116, 00049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdi, J.; Kim, J. Intelligent pump operation and river diversion systems for urban storm management. J. Hydrol. Eng. 2015, 20, 04015031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, C.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, C.; Zhao, Z.; Yin, X.; Yang, J. Does the upstream gate control scheme threaten the safety of extra-long pressurized water diversion tunnel: Gas–liquid evolution characteristics of the filling process. Phys. Fluids 2024, 36, 094130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Du, S. Analysis on Water Hammer Resistant Characteristics of Pipeline Valves. Curr. Sci. 2025, 5, 5152–5164. [Google Scholar]

- Lescovich, J.E. The control of water hammer by automatic valves. J.-Am. Water Work. Assoc. 1967, 59, 632–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Liu, Y. Research on two-way flow passage self-irrigation and self-draining of gate open control based on CFX. China Rural Water Hydropower 2017, 7, 140–143. [Google Scholar]

- Song, J. Application of Pump Gate in Inland River Water Treatment in Fuzhou. Fujian Archit. 2018, 7, 140–142. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, K. Pump Stations for Flood Harvesting or Irrigation Downstream of a Storage Dam; A Technical Report from the CSIRO Victoria and Southern Gulf Water Resource Assessments for the National Water Grid; CSIRO: Canberra, Australia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Guo, X.; Chen, Y.; Yang, C.; Liu, S.; Guo, L. Research on the characteristics and protection of water hammer in long-distance dual-pipe water supply systems. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0314998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohrasbi, A.; Attarnejad, R. Water hammer analysis by characteristic method. Am. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2008, 1, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Q.; Du, J.; Liu, M.; Liu, Y.; Huang, J.; Yu, W.; Yuan, F.; Wang, D.; Yang, X. Experimental study on the effects of two-stage valve closure on the maximum water hammer pressure in micro-hydroelectric system. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 65, 105886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Wei, C. Determination of the Area of Flap Valve in Rapid-Drop Gate of Large Vertical Axial Flow Pumping Station. S.–N. Water Transf. Water Sci. Technol. 2010, 8, 6–8. [Google Scholar]

- Bettaieb, N.; Taieb, E.H. Assessment of failure modes caused by water hammer and investigation of convenient control measures. J. Pipeline Syst. Eng. Pract. 2020, 11, 04020006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Jiang, Y.; Song, X.; Tang, F.; Dai, J.; Yang, F.; Wang, H.; Shi, L. Investigation on the influence of flap valve area on transition process of large axial flow pump system. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wylie, E.B.; Streeter, V.L. Fluid Transients; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, D.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X. New suter-transformation method of complete characteristic curves of pump-turbines based on the 3-D surface. China Rural Water Hydropower 2015, 1, 143–145. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Water Resources of the People’s Republic of China. Specification for Design of Steel Gate in Hydraulic and Hydroelectric Engineering: SL 74-2013; China Water & Power Press: Beijing, China, 2013. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

| No. | Length (m) | Width (m) | Height (m) | Elevation of Pipe Centerline (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5.26 | 4.20 | 6.47 | 5.27 |

| 2 | 6.20 | 3.60 | 4.47 | 4.02 |

| 3 | 2.80 | 4.35 | 3.64 | 4.18 |

| 4 | 7.00 | 3.60 | 3.30 | 4.35 |

| 5 | 4.00 | 3.60 | 7.12 | 2.44 |

| 6 | 8.50 | 3.60 | 6.05 | 2.97 |

| 7 | 5.09 | 3.60 | 5.06 | 3.47 |

| 8 | 8.50 | 3.60 | 4.03 | 4.00 |

| 9 | 33.20 | 3.60 | 3.00 | 4.50 |

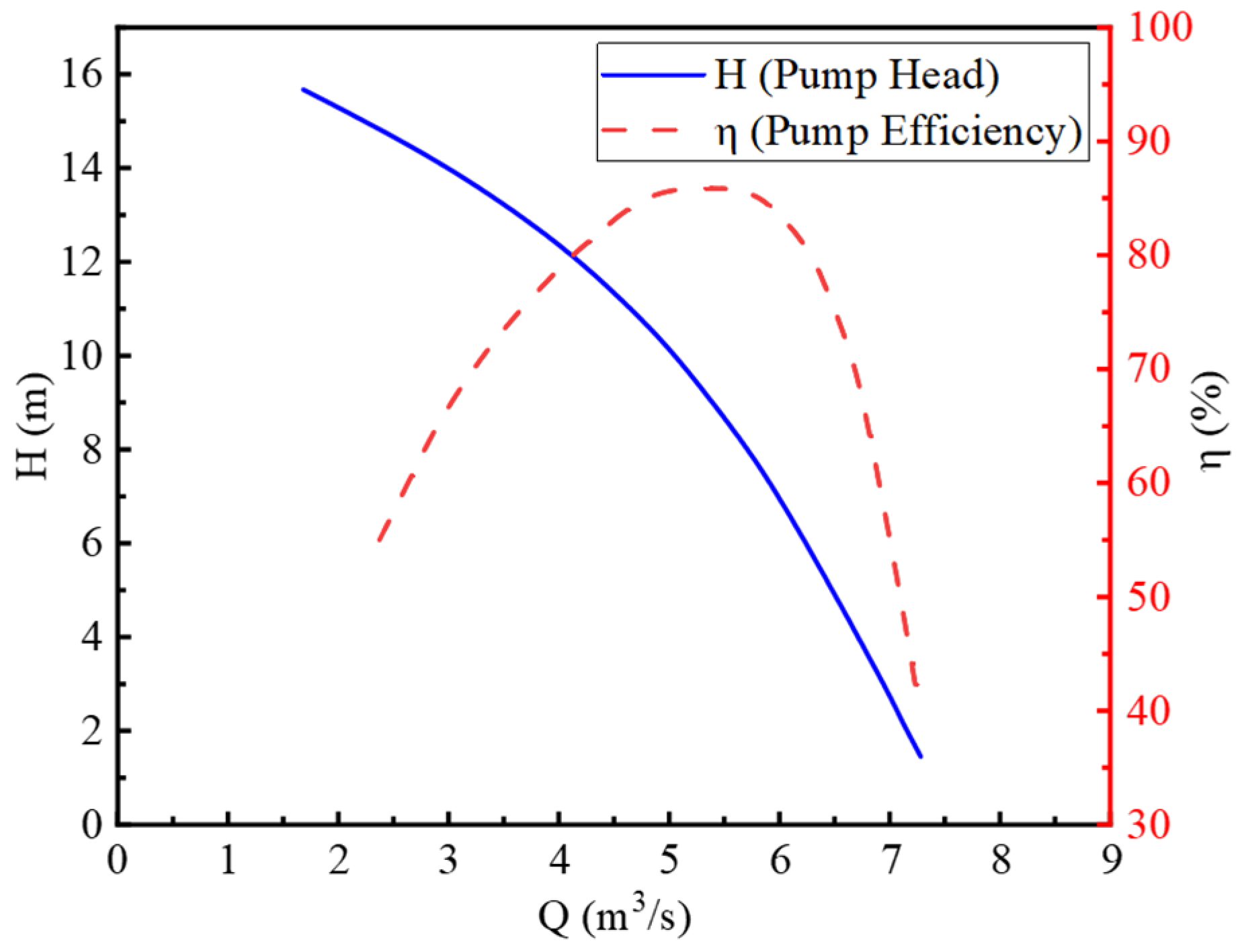

| Design Head (m) | Design Discharge (m3/s) | Rated Speed (r/min) | Rated Power (kW) | Moment of Inertia (kg·m2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8.51 | 5.56 | 365 | 710 | 88.75 |

| Sump | Minimum Water Level (m) | Design Water Level (m) | Maximum Water Level (m) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Suction Sump | 3.68 | 5.03 | 7.35 |

| Outlet Sump | 3.73 | 12.19 | 13.74 |

| Case | Method | Flap Valve | #1 Sluice Gate Closure Time (s) | #2 Sluice Gate Closure Time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1.1 | Single Gate Closure (#1) | Failure | 120 | Remains fully open |

| Case 1.2 | Single Gate Closure (#2) | Failure | Remains fully open | 120 |

| Case 1.3 | Asynchronous Dual-Gate Closure (Fast–Slow) | Failure | 60 | 120 |

| Case 1.4 | Synchronized Dual-Gate Slow Closure | Failure | 120 | 120 |

| Case 1.5 | Synchronized Dual-Gate Fast Closure | Failure | 60 | 60 |

| Case | Method | Flap Valve | #1 Sluice Gate Closure Time (s) | #2 Sluice Gate Closure Time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 2.1 | Single Gate Closure (#1) | Normal closure | 120 | Remains fully open |

| Case 2.2 | Single Gate Closure (#2) | Normal closure | Remains fully open | 120 |

| Case 2.3 | Asynchronous Dual-Gate Closure (Fast–Slow) | Normal closure | 60 | 120 |

| Case 2.4 | Synchronized Dual-Gate Slow Closure | Normal closure | 120 | 120 |

| Case 2.5 | Synchronized Dual-Gate Fast Closure | Normal closure | 60 | 60 |

| Case | Maximum Pump Reverse Speed (%) | Maximum Pressure Along the Channel (m) | Minimum Pressure Along the Channel (m) | Does the Pump Speed Meet the Control Standard | Does the Pressure Meet the Control Standard | Maximum Sustained Oscillation Duration (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1.1 | −150.44 | 11.48 | −0.56 | No | Yes | Persistent |

| Case 1.2 | −150.39 | 11.42 | −0.53 | No | Yes | Persistent |

| Case 1.3 | −147.25 | 11.70 | −0.56 | Yes | Yes | 120 |

| Case 1.4 | −150.18 | 11.42 | −0.45 | No | Yes | 120 |

| Case 1.5 | −149.92 | 11.40 | −0.67 | Yes | Yes | 60 |

| Case | Maximum Pump Reverse Speed (%) | Maximum Pressure Along the Channel (m) | Minimum Pressure Along the Channel (m) | Pump Speed Meets the Control Standard | Pressure Meets the Control Standard | Maximum Sustained Oscillation Duration (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 2.1 | 0.07 | 13.52 | −2.22 | Yes | Yes | Persistent |

| Case 2.2 | 0.07 | 13.50 | −2.22 | Yes | Yes | 120 |

| Case 2.3 | 0.08 | 16.80 | −1.32 | Yes | Yes | 120 |

| Case 2.4 | 0.07 | 13.51 | −2.22 | Yes | Yes | 120 |

| Case 2.5 | 0.07 | 13.51 | −2.22 | Yes | Yes | 60 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, R.; Hu, J.; Wang, L.; Du, T.; Song, M.; Gao, H.; Mao, J.; Zhang, Z.; Fang, Y. Research on Water Hammer Protection in Coastal Drainage Pumping Stations Based on the Combined Application of Flap Valve and Sluice Gate. Water 2026, 18, 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010025

Zhang R, Hu J, Wang L, Du T, Song M, Gao H, Mao J, Zhang Z, Fang Y. Research on Water Hammer Protection in Coastal Drainage Pumping Stations Based on the Combined Application of Flap Valve and Sluice Gate. Water. 2026; 18(1):25. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010025

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Runlong, Jianyong Hu, Linghua Wang, Taowei Du, Mingming Song, Haijing Gao, Jiahua Mao, Zhen Zhang, and Yunrui Fang. 2026. "Research on Water Hammer Protection in Coastal Drainage Pumping Stations Based on the Combined Application of Flap Valve and Sluice Gate" Water 18, no. 1: 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010025

APA StyleZhang, R., Hu, J., Wang, L., Du, T., Song, M., Gao, H., Mao, J., Zhang, Z., & Fang, Y. (2026). Research on Water Hammer Protection in Coastal Drainage Pumping Stations Based on the Combined Application of Flap Valve and Sluice Gate. Water, 18(1), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010025