Grading Evaluation of Grouting Seal Quality for Recharge Channels in Water-Hazardous Aquifers of Extremely Complex Mines

Abstract

1. Introduction

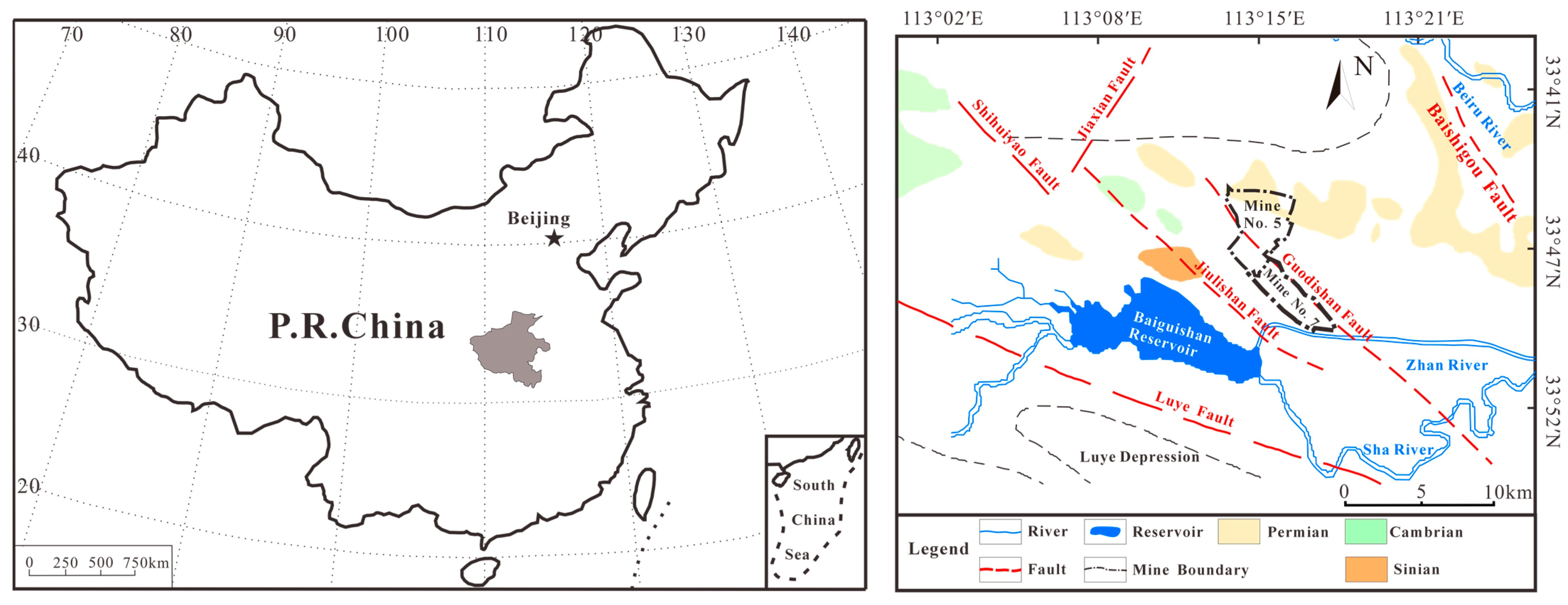

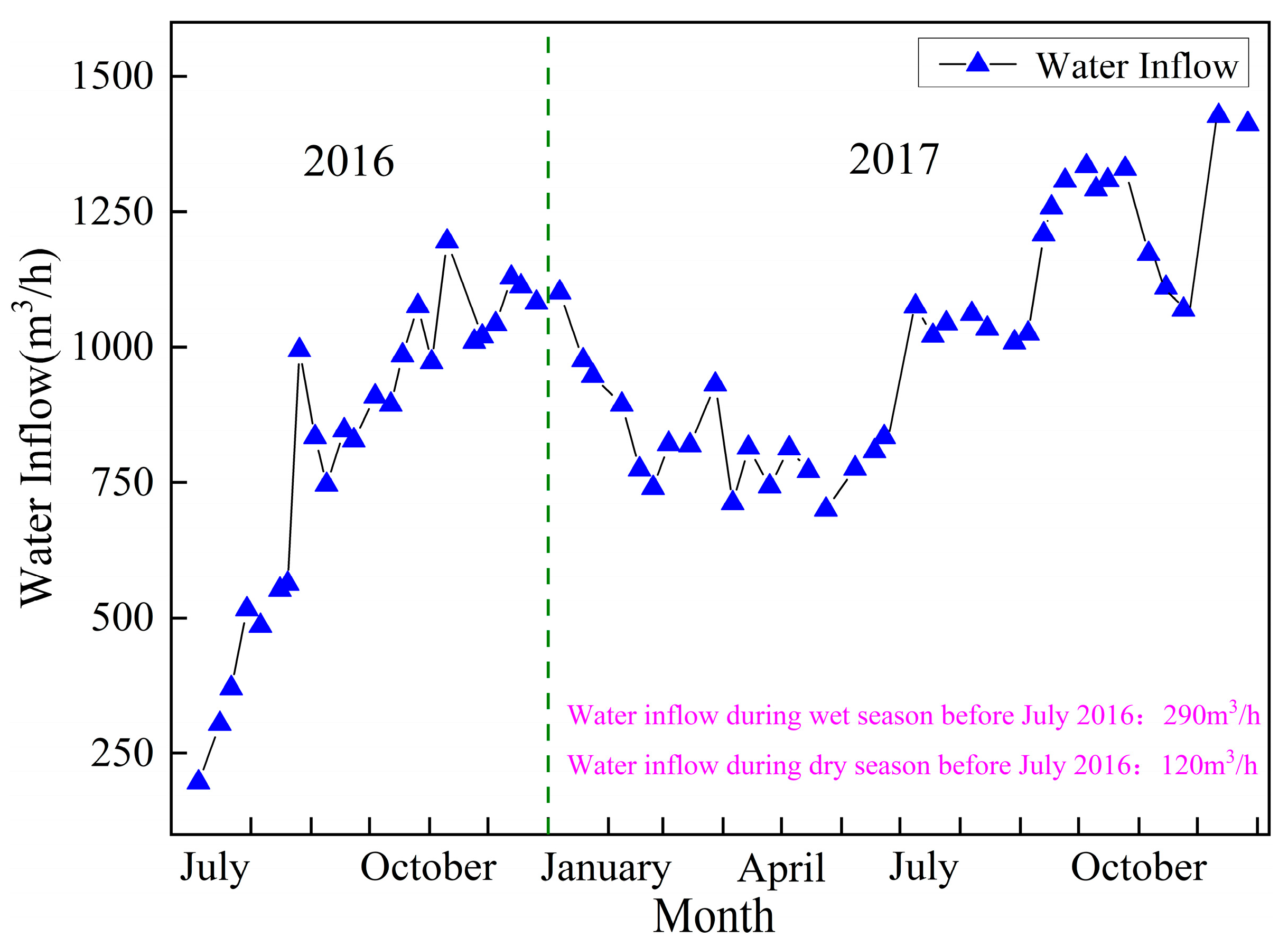

2. Project Background and Implementation

2.1. Project Background

2.2. Project Implementation

2.3. Project Outcomes

3. Development of an Evaluation Indicator System

3.1. Establishment of the Indicator System

3.1.1. Grout Volume

3.1.2. Grout Volume per Unit Time

3.1.3. Grout Volume per Unit Thickness

3.1.4. Final Borehole Pressure

3.1.5. Penetration Depth into Cambrian Limestone

3.1.6. Variation in Rock Mechanical Strength

3.2. Quantification of Indicator Factors

4. Quality Assessment Method for Sealing

4.1. Analytic Hierarchy Process

4.1.1. Judgment Matrix Construction

4.1.2. Consistency Test

4.2. Entropy Weight Method

4.2.1. Construction of the Judgment Matrix

4.2.2. Weight Determination

4.3. Combination Weighting Method

4.4. TOPSIS Model

4.4.1. Matrix Construction

4.4.2. Determination of Ideal Solutions

4.4.3. Weighted Distance Calculation

4.4.4. Adherence Calculation

5. Classification of Sealing Effectiveness

5.1. Weighting of Indicator Factors

5.1.1. Subjective Weighting

5.1.2. Objective Weighting

5.1.3. Combined Weight

5.2. Grouting Effectiveness Evaluation

5.3. Discussion

6. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wu, Q.; Li, S. Positive and negative environmental effects of closed mines and its countermeasures. J. China Coal Soc. 2018, 43, 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Gui, H.; Qiu, H.; Qiu, W.; Tong, S.; Zhang, H. Overview of goaf water hazards control in China coalmines. Arab. J. Geosci. 2018, 11, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Gai, Q.; Huang, L.; Yu, Y.; Shen, X.; Pang, L. Influence of water accumulation in closed mine on water prevention andcontrol in adjacent production mines. Coal Sci. Technol. 2020, 48, 96–101. [Google Scholar]

- Rudakov, D.; Sharifi, S.; Westermann, S. An Empirical–Analytical Model of Mine Water Level Rebound. Mining 2025, 5, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gee, D.; Bateson, L.; Novellino, A.; Sowter, A.; Wyatt, L.; Marsh, S.; Morgenstern, R.; Athab, A. Modelling groundwater rebound in recently abandoned coalfields using DInSAR. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 249, 112021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komine, H. Evaluation of chemical grouted soil by electrical resistivity. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Ground Improv. 1997, 1, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher, L.; Marilyn, D.; John-S, M. Grouting Verification Using 3-D Seismic Tomography. In Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Grouting and Deep Mixing 2012: American Society of Civil Engineers, New Orleans, LA, USA, 15–18 February 2012; pp. 1506–1515. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, W. Real-time analysis of goaf grouting effect using speculative method groundon water level change. Coal Eng. 2025, 57, 50–57. [Google Scholar]

- Li, R. Optimization of parameter control and evaluation of grouting effectiveness for the curtain grouting project at Jianshan Phosphate Mine. Master’s Thesis, Kunming University of Science and Technology, Kunming, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Li, W.; Xue, F.; Wang, K.; Zhang, C.; Song, T. Comprehensive evaluation of TOPSIS-RSR grouting effect based onsubjective and objective combined weight. Coal Sci. Technol. 2023, 51, 191–199. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, S.; Wang, J.; Zhang, W.; Han, C.; Wang, G.; Jia, D.; Liu, L.; Guo, H. Ealuation system of grouting effect of coal seam floor based on TOPSIS-RSR method with combination weighting. J. Min. Strat. Control Eng. 2024, 6, 140–151. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Ji, Z.; Jiang, D. Evaluation of grouting reinforcement effectiveness in fractured coal and rock mass based on mathematical methods. Math. Pract. Theory 2024, 54, 220–227. [Google Scholar]

- Zadhesh, J.; Rastegar, F.; Sharifi, F.; Amini, H. Consolidation Grouting Quality Assessment using Artificial Neural Network (ANN). Indian Geotech. J. 2015, 45, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Jia, D.; Chen, J.; Fu, Z.; Chen, J.; Guo, H.; Liu, L. Intelligent evaluation method of directional drilling grouting effectin limestone aquifer. Coal Eng. 2024, 56, 63–69. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, S.; Fu, X.; Xie, B. Comprehensive Evaluation Method for the Grouting Management Effect of Mine Water Hazards Based on the Combined Assignment of the TOPSIS and RSR Methods. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Jin, M.; Wang, D. Evaluation of Grouting Reinforcement Effectiveness in Coal Seam Floors Using the Monte Carlo Analytical Hierarchy Process: A Case Study of the Rongkang Coal Mine. Acs Omega 2025, 10, 31410–31427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Chen, L.; Tian, F.; Zhao, L. Comprehensive evaluation model of coal mine safety under the combination of game theory and TOPSIS. Math. Probl. Eng. 2022, 2022, 5623282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Chen, J.; Zhu, J.; Ji, X.; Fu, Z. Research on factor analysis and method for evaluating grouting effects using machine learning. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 7782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, J.; Xu, Y.; Xie, D.; Liu, C.; Zhong, C. The risk assessment of water bursting based on combination rule of distance function. China Min. Mag. 2021, 21, 949–956. [Google Scholar]

- Sang, X.; Luo, W.; Zhong, P.; Yang, C. Risk assessment of mine water inrush based oncombined weights-TOPSIS method. China Min. Mag. 2024, 33, 397–402. [Google Scholar]

- Song, J.; Zhang, M. Safety risk assessment of rapid excavation working face based onAHP-TOPSIS. China Min. Mag. 2024, 33, 354–358. [Google Scholar]

- Dursun, A.E. Fatal accident analysis and hazard identification in Turkish coal-extracting industry using analytic hierarchy process. Min. Metall. Explor. 2024, 41, 149–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, C.; Fan, C.; Li, S.; Liu, X.; Wang, X.; Luo, M.; Yang, Z. Optimization of support parameters of development roadway passingthrough collapse column based on AHP−entropy weight combination. Coal Sci. Technol. 2025, 53, 187−201. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, L.; Fu, S.; Han, J.; Liu, T.; Zhan, S.; Wang, C. The mine emergency management capability based on EWM-CNN comprehensive evaluation. Eng. Manag. J. 2024, 36, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.; Alp, N.; Shi, J.; Wang, C.; Zhang, X.; Chen, H. Multi-criteria building energy performance benchmarking through variable clustering based compromise TOPSIS with objective entropy weighting. Energy 2017, 125, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, K.; Liu, L.; Xin, J.; Yang, H.; Gao, C. Application of the Entropy Weight and TOPSIS Method in Safety Evaluation of Coal Mines. Procedia Eng. 2011, 26, 2085–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Z.; Yun, Y.; Sun, J. Entropy method for determination of weight of evaluating indicators in fuzzy synthetic evaluation for water quality assessment. J. Environ. Sci. 2006, 18, 1020–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, M.; Zhao, J.; Shao, Z.; Zhang, W.; Zheng, Y.; Yin, X.; Gai, G.; Han, S. Risk assessment of water inrush from coal seam floor based on combinationweighting method and vulnerability index model. Coal Eng. 2025, 57, 160–168. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, T.; Wang, S. Evaluation on Urban Public Security Sense Based on Combined Weighting and Grey Correlation. Stat. Decis. 2019, 35, 45–50. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, J.; Ping, Y.; Hao, J.; Ren, J.; Meng, J.; Wang, X. Water inrush risk assessment of coal seam floor based on interval weight and unascertained measure theory. Ground Water 2023, 45, 1–6+25. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, F.; Yang, H.; Wang, H.; Jin, F.; Song, Z. Coal mine safety investment decision model based on combination empowerment and SPA-TOPSIS. China Saf. Sci. J. 2024, 34, 86–92. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, M.; Kou, X.; Yan, D.; Dong, P.; Wei, X.; Zhang, B. Safety risk assessment of underground mines based on combined weighting-TOPSIS. Min. Metall. Eng. 2025, 45, 35–40. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C. Extensions of the TOPSIS for group decision-making under fuzzy environment. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2000, 114, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Recharge Channel | No.1 | No.2 | No.3 | No.4 | No.5 | No.6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Borehole Numbers | A1~A3, B1~B2 | A4~A6, B3~B4 | A7~A12, B5~B8 | A13~A15, B9~B10 | A16~A18, B11~B12 | A19~A24, B13~B16 |

| Number of Boreholes | 5 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 5 | 10 |

| Pumping Test | Time Period | Duration (h) | Pumping Volume | Water Level (m) | Fluctuation (Decline) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First | 17 June 2022 16:54~25 June 15:50 | 190.93 | 696.93 | −121.9−122.6 | 0.7 |

| Second | 11 January 2023 10:10~14 January 11:55 | 73.75 | 683.89 | −121.3−122.6 | 1.3 |

| Third | 27 March 2023 11:05~28 March 1:23 | 14.3 | 683.89 | −123.5−123.9 | 0.4 |

| No. | June 2022 | January 2023 | March 2023 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water Level (m) | Water Level (m) | Water Level (m) | ||||

| 1 | −122.6~−122.5 | 29.44 | −122.6~−122.5 | 11,910.48 | −123.5~−123.6 | 8370.34 |

| 2 | −122.5~−122.4 | 29.37 | −122.5~−122.4 | 11,910.48 | −123.6~−123.7 | 8370.34 |

| 3 | −122.4~−122.3 | 407.65 | −122.4~−122.3 | 8360.24 | −123.7~−123.8 | 8370.34 |

| 4 | −122.3~−122.2 | 409.26 | −122.3~−122.2 | 986.38 | −123.8~−123.9 | 8370.34 |

| 5 | −122.2~−122.1 | 642.56 | −122.2~−122.1 | 562.88 | N/A | N/A |

| 6 | −122.1~−122.0 | 4592.59 | −122.1~−122.0 | 6089.03 | N/A | N/A |

| 7 | −122.0~−121.9 | 6110.87 | −122.0~−121.9 | 4777.11 | N/A | N/A |

| 8 | −121.9~−121.8 | 5671.63 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 9 | −121.8~−121.7 | 6944.09 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 10 | −121.7~−121.6 | 9972.46 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 11 | −121.6~−121.5 | 14,032.39 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 12 | −121.5~−121.4 | 13,534.86 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 13 | −121.4~−121.3 | 11,281.20 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Mean | 1745.96 | 8156.40 | 8370.34 | |||

| Time | Dry Season | Wet Season | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before Grouting | After Grouting | Before Grouting | After Grouting | |

| Mine No.7 Dynamic Recharge | 690.53 | 449.75 | 1500 | 621.43 |

| Recharge Channel | Borehole No. | Grout Volume (t) | Grout Volume per Unit Time (m3/h) | Grout Volume per Unit Thickness (t/m) | Final Borehole Pressure (Mpa) | Penetration Depth into Cambrian Limestone (m) | Variation in Rock Mechanical Strength ([-]) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No.1 | A1 | 452.41 | 6.96 | 8.32 | 1.5 | 51.9 | 1.0173 |

| A2 | 895.38 | 7.39 | 16.87 | 1.5 | 50.35 | 1.0173 | |

| A3 | 569.35 | 6.69 | 10.58 | 1.5 | 50.59 | 1.0173 | |

| B1 | 863.67 | 8.43 | 15.33 | 1.6 | 53.33 | 1.0173 | |

| B2 | 136 | 9.75 | 2.52 | 1.7 | 50.7 | 1.0173 | |

| No.2 | A4 | 412.79 | 9.6 | 7.35 | 3.5 | 94.17 | 1.2594 |

| A5 | 455.6 | 8.99 | 8.22 | 3.9 | 50 | 1.2594 | |

| A6 | 522.22 | 9.17 | 3.07 | 3 | 164.76 | 1.2594 | |

| B3 | 1509.43 | 8.94 | 27.39 | 3.1 | 50.5 | 1.2594 | |

| B4 | 652.68 | 9.75 | 11.16 | 3.1 | 50.49 | 1.2594 | |

| No.3 | A7 | 241.09 | 7.79 | 4.50 | 1.6 | 56.72 | 1.3109 |

| A8 | 1174.8 | 8.62 | 25.48 | 2 | 53.6 | 1.3109 | |

| A9 | 1055.86 | 10.56 | 20.78 | 1.7 | 53.8 | 1.3109 | |

| A10 | 911.26 | 10.43 | 17.27 | 1.5 | 55.76 | 1.3109 | |

| A11 | 645.49 | 7.80 | 12.63 | 1.5 | 54.8 | 1.3109 | |

| A12 | 519.8 | 11.55 | 9.92 | 1.7 | 55.9 | 1.3109 | |

| B5 | 728.66 | 8.88 | 14.44 | 1.8 | 53.8 | 1.3109 | |

| B6 | 1408.76 | 9.44 | 32.76 | 1.5 | 54.8 | 1.3109 | |

| B7 | 463.76 | 8.90 | 9.45 | 1.6 | 52.5 | 1.3109 | |

| B8 | 958.40 | 12.15 | 19.36 | 2.1 | 53.4 | 1.3109 | |

| No.4 | A13 | 212 | 7.16 | 1.84 | 3.1 | 54.56 | 1.355 |

| A14 | 176 | 6.56 | 1.25 | 3.2 | 83 | 1.355 | |

| A15 | 536 | 10.53 | 4.69 | 3.3 | 52 | 1.355 | |

| B9 | 224 | 9.40 | 1.94 | 3.2 | 63.05 | 1.355 | |

| B10 | 480 | 8.74 | 4.20 | 3.5 | 53 | 1.355 | |

| No.5 | A16 | 853.56 | 8.69 | 8.09 | 2.1 | 108.5 | 1.0701 |

| A17 | 413.18 | 8.04 | 8.11 | 1.5 | 55.06 | 1.0701 | |

| A18 | 318.86 | 9.84 | 6.31 | 1.6 | 54.4 | 1.0701 | |

| B11 | 489.95 | 8.19 | 9.76 | 1.6 | 55.4 | 1.0701 | |

| B12 | 388.85 | 7.57 | 7.73 | 1.6 | 54.6 | 1.0701 | |

| No.6 | A19 | 986 | 8.82 | 4.96 | 3 | 85.3 | 1.3074 |

| A20 | 980 | 9.45 | 5.69 | 3.2 | 57 | 1.3074 | |

| A21 | 2054.4 | 9.76 | 9.96 | 0 | 90.62 | 1.3074 | |

| A22 | 1638 | 10.04 | 8.77 | 3 | 87.87 | 1.3074 | |

| A23 | 616 | 5.97 | 6.34 | 3.2 | 88.3 | 1.3074 | |

| A24 | 264 | 5.73 | 2.61 | 3 | 89.75 | 1.3074 | |

| B13 | 1050 | 9.42 | 5.25 | 3 | 86.81 | 1.3074 | |

| B14 | 1174 | 8.31 | 5.61 | 3 | 84 | 1.3074 | |

| B15 | 424 | 7.20 | 4.22 | 3.2 | 90.3 | 1.3074 | |

| B16 | 696 | 6.17 | 6.98 | 3.1 | 89 | 1.3074 |

| Scale | Meaning of the Scale |

|---|---|

| 1 | Factor i is as important as factor j. |

| 3 | Factor i is slightly more important than factor j. |

| 5 | Factor i is moderately more important than factor j. |

| 7 | Factor i is strongly more important than factor j. |

| 9 | Factor i is extremely more important than factor j. |

| 2, 4, 6, 8 | Intermediate values between the above judgments. |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

| RI | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.58 | 0.90 | 1.12 | 1.24 | 1.32 | 1.41 | 1.45 |

| Secondary Indicators | Weight | Third-Level Indicators | Weight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grouting Volume Characteristics | 0.5056 | Grouting Volume | 0.1798 |

| Grout volume per unit time | 0.0427 | ||

| Grout volume per unit thickness | 0.2831 | ||

| Grouting parameters | 0.2642 | Final borehole pressure | 0.2642 |

| Final hole stratum | 0.1434 | Depth of Cambrian limestone | 0.1434 |

| Stratigraphic characteristics | 0.0868 | Variation in Rock Mechanical Strength | 0.0868 |

| Evaluation Indicator | Grout Volume | Grout Volume per Unit Time | Grout Volume per Unit Thickness | Final Borehole Pressure | Depth of Cambrian limestone | Variation in Rock Mechanical Strength |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Combined weighting | 0.2453 | 0.0348 | 0.3667 | 0.2051 | 0.1197 | 0.0283 |

| Recharge Channel | Borehole No. | Mean | Recharge Channel | Borehole No. | Mean | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NO.1 | A1 | 0.1452 | 0.0416 | 0.223 | 0.298 | NO.4 | A13 | 0.1737 | 0.0404 | 0.189 | 0.212 |

| A2 | 0.1029 | 0.0848 | 0.452 | A14 | 0.1758 | 0.0424 | 0.194 | ||||

| A3 | 0.1339 | 0.0526 | 0.282 | A15 | 0.1548 | 0.0495 | 0.242 | ||||

| B1 | 0.1086 | 0.0781 | 0.418 | B9 | 0.1725 | 0.0419 | 0.196 | ||||

| B2 | 0.1750 | 0.0229 | 0.116 | B10 | 0.1579 | 0.0501 | 0.241 | ||||

| NO.2 | A4 | 0.1448 | 0.0566 | 0.281 | 0.387 | NO.5 | A16 | 0.1334 | 0.0563 | 0.297 | 0.231 |

| A5 | 0.1422 | 0.0623 | 0.305 | A17 | 0.1468 | 0.0402 | 0.215 | ||||

| A6 | 0.1592 | 0.0533 | 0.251 | A18 | 0.1558 | 0.0330 | 0.175 | ||||

| B3 | 0.0484 | 0.1460 | 0.751 | B11 | 0.1383 | 0.0485 | 0.260 | ||||

| B4 | 0.1263 | 0.0666 | 0.345 | B12 | 0.1486 | 0.0391 | 0.208 | ||||

| NO.3 | A7 | 0.1646 | 0.0264 | 0.138 | 0.434 | NO.6 | A19 | 0.1439 | 0.0590 | 0.291 | 0.308 |

| A8 | 0.0662 | 0.1281 | 0.659 | A20 | 0.1419 | 0.0610 | 0.301 | ||||

| A9 | 0.0844 | 0.1051 | 0.554 | A21 | 0.1216 | 0.0993 | 0.450 | ||||

| A10 | 0.1006 | 0.0869 | 0.463 | A22 | 0.1186 | 0.0884 | 0.427 | ||||

| A11 | 0.1241 | 0.0624 | 0.335 | A23 | 0.1447 | 0.0540 | 0.272 | ||||

| A12 | 0.1367 | 0.0503 | 0.269 | A24 | 0.1681 | 0.0412 | 0.197 | ||||

| B5 | 0.1144 | 0.0727 | 0.388 | B13 | 0.1415 | 0.0616 | 0.303 | ||||

| B6 | 0.0523 | 0.1630 | 0.757 | B14 | 0.1382 | 0.0661 | 0.324 | ||||

| B7 | 0.1403 | 0.0469 | 0.250 | B15 | 0.1576 | 0.0470 | 0.230 | ||||

| B8 | 0.0902 | 0.0985 | 0.522 | B16 | 0.1404 | 0.0561 | 0.286 |

| Recharge Channel | No.1 | No.2 | No.3 | No.4 | No.5 | No.6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Borehole exposure rate (%) | 20 | 100 | 50 | 0 | 20 | 0 |

| Cave height (m) | 1.17 | 4.99 | 4.71 | N/A | 4.51 | N/A |

| Cambrian limestone exposure rate (%) | 2.7 | 8.66 | 13.26 | N/A | 8.19 | N/A |

| Old voids rate (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| Channel | AHP Score | AHP Rank | EWM Score | EWM Rank | Combined Score | Combined Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NO.3 | 0.425227 | 2 | 0.437869 | 1 | 0.433854 | 1 |

| NO.2 | 0.441987 | 1 | 0.351323 | 2 | 0.386961 | 2 |

| NO.6 | 0.360964 | 3 | 0.279225 | 4 | 0.308139 | 3 |

| NO.1 | 0.308547 | 4 | 0.290784 | 3 | 0.298432 | 4 |

| NO.5 | 0.258220 | 6 | 0.217675 | 5 | 0.231217 | 5 |

| NO.4 | 0.300994 | 5 | 0.150189 | 6 | 0.212955 | 6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

He, J.; Li, H.; Huang, Y.; Tian, S.; Yue, J.; Meng, H.; Wang, Q.; Wang, X. Grading Evaluation of Grouting Seal Quality for Recharge Channels in Water-Hazardous Aquifers of Extremely Complex Mines. Water 2026, 18, 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010121

He J, Li H, Huang Y, Tian S, Yue J, Meng H, Wang Q, Wang X. Grading Evaluation of Grouting Seal Quality for Recharge Channels in Water-Hazardous Aquifers of Extremely Complex Mines. Water. 2026; 18(1):121. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010121

Chicago/Turabian StyleHe, Jianggen, Hankun Li, Yaolong Huang, Shiyuan Tian, Junchao Yue, Hongwei Meng, Qi Wang, and Xinyi Wang. 2026. "Grading Evaluation of Grouting Seal Quality for Recharge Channels in Water-Hazardous Aquifers of Extremely Complex Mines" Water 18, no. 1: 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010121

APA StyleHe, J., Li, H., Huang, Y., Tian, S., Yue, J., Meng, H., Wang, Q., & Wang, X. (2026). Grading Evaluation of Grouting Seal Quality for Recharge Channels in Water-Hazardous Aquifers of Extremely Complex Mines. Water, 18(1), 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010121