Effects of Short, Flexible Fibers on Clogging and Erosion in a Sewage Pump

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Governing Equations and Models

2.1. Governing Equations

2.2. Flexible Fiber Model and Di Felice Model Drag Model

2.3. IEEM Erosion Model

2.4. Model Assumptions and Limitations

3. Configuration Setups and Verifications

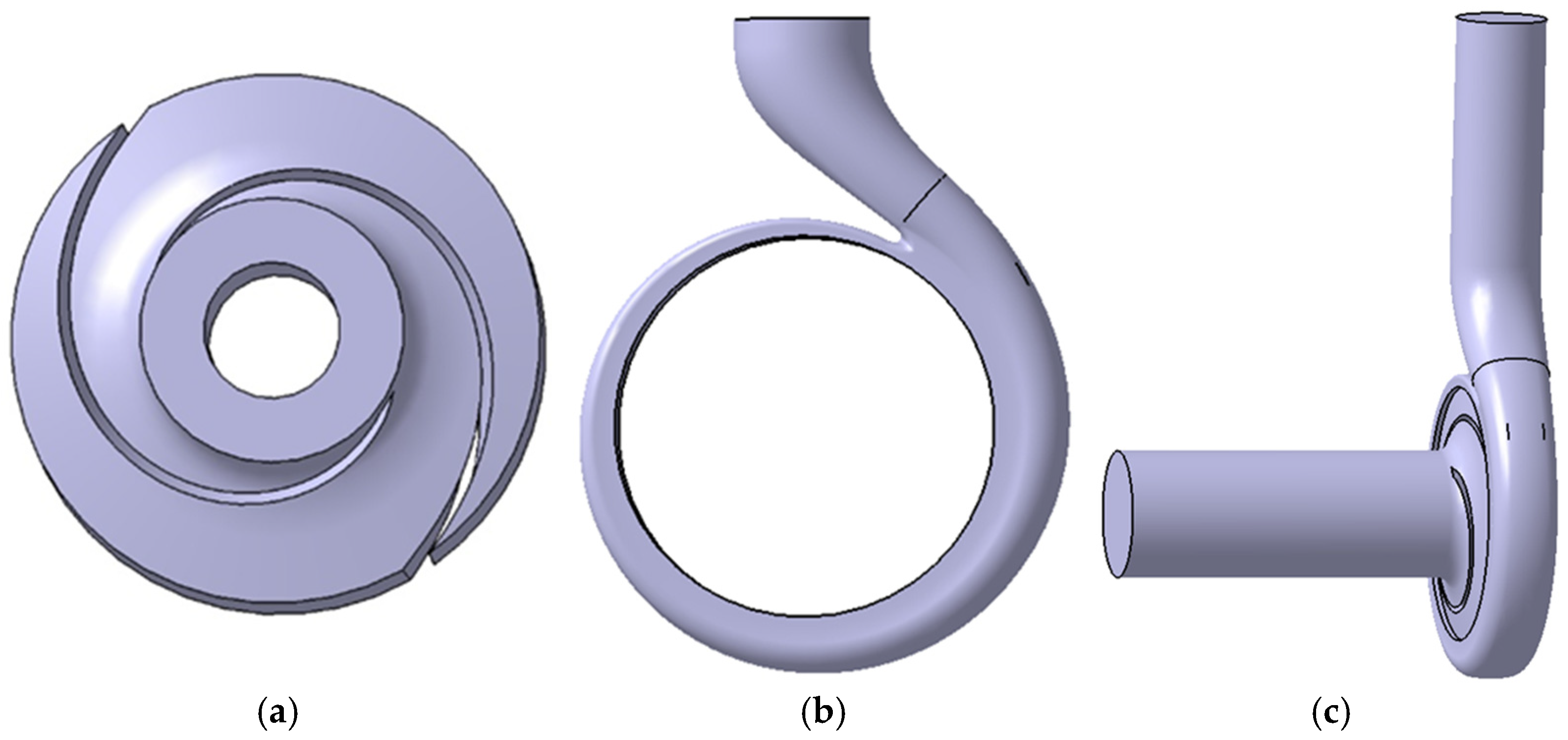

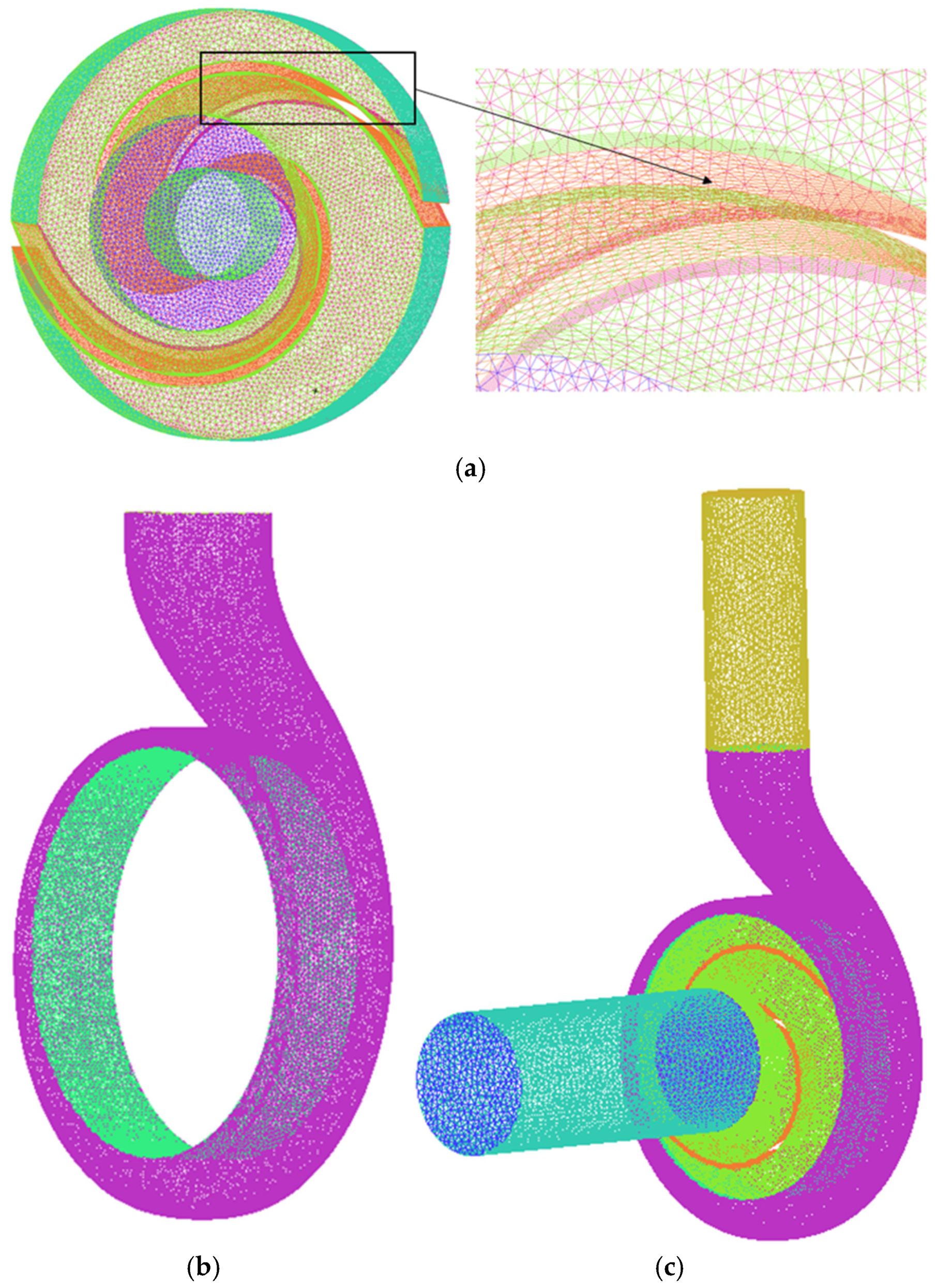

3.1. Fluid Domain and Mesh Information Within the Pump

3.2. Boundary Conditions and Setting

3.3. Reliability Verification

4. Results and Discussions

4.1. Flow State with Fiber Only

4.1.1. Effect of Inlet Positions of Fibers on Clogging

4.1.2. Effect of Fiber Diameter on Clogging

4.1.3. Effect of Fibers on Erosion Rates

4.2. Flow State of Fibers and Particles Together

4.2.1. Effect of Fibers and Particles Together on Clogging

4.2.2. Effect of Fibers and Particles Together on Erosion

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Fibers undergo deformations such as bending and twisting under the influence of the rotating flow field of the impeller. In the inlet pipe, the fiber moves linearly in a stable manner, but under the action of pre-rotation, the fiber deforms before entering the impeller domain, and the deformation of the fiber near the wall occurs earlier than in the center. In the volute, the fibers move along the wall away from the tongue and eventually out of the outlet pipe to the outside of the sewage pump. The movement of the fibers changes with the position of the inlet, and fibers in the center are more likely to collide with the shaft and remain in the inlet area. Additionally, as the particle diameter increases, the fibers stay in the pump body longer and the motion track is closer to the impeller working surface.

- (2)

- The interaction between fibers and particles affects the location and size of erosion. The fibers themselves do not have a significant impact on erosion, but the interaction between fibers and particles results in more irregular pitting at the impeller of the sewage pump. As the fiber concentration increases, the overall erosion rate in the sewage pump increases significantly, and the distribution of erosion shows a random and uniform character.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhao, B.T.; Ye, B.B.; Tao, R.H.; Cao, G.W.; Wu, F. Design of new non-clogging self-priming sewage pump. J. Mech. Electr. Eng. 2012, 29, 806–809. [Google Scholar]

- Moloshnuy, O.; Szulc, P.; Moliński, G. The analysis of the performance of a sewage pump in terms of the wear of hydraulic components. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1741, 012015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.H.; Zhu, M.Y. Simulation study on attrition to centrifugal sewerage pump. Key Eng. Mater. 2011, 1244, 474–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Shi, W.; Zhang, D.; Cao, W.; Xing, J. Numerical simulation of solid–liquid two-phase turbulent flow of swept-back double blades sewage pump. J. Drain. Irrig. Mach. Eng. 2015, 33, 116–122. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, A.; Zou, Z.P.; Zhou, D.Q.; Zheng, Y.; Luo, X.W. Investigation of the correlation mechanism between cavitation rope behavior and pressure fluctuations in a hydraulic turbine. Renew. Energy 2020, 147, 1199–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roelofs, F. Liquid metal thermal hydraulics: State-of-the-art and future perspectives. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2020, 362, 110590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, P.P.; Luo, M.T.; Li, F.Y.; Qi, X.G.; Huo, A.D.; Wang, Z.H.; He, B.; Takara, K.; Nover, D. Urban flood numerical simulation: Research, methods and future perspectives. Environ. Model. Softw. 2022, 156, 105478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.Y.; Fu, X.L.; Zuo, Z.G.; Wang, H.J.; Li, Z.J.; Liu, S.H.; Wei, X.Z. Investigation methods for analysis of transient phenomena concerning design and operation of hydraulic-machine systems—A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 101, 26–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomassi, G.; Romano, P.; Di Giacomo, G. Modern use of water produced by purification of municipal wastewater: A case study. Energies 2021, 14, 7610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marouek, J.; Marouková, A. Economic considerations on nutrient utilization in wastewater management. Energies 2021, 14, 3468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engin, T.; Gur, M.; Calli, I. Slurry and tip clearance effects on the performance of an open impeller centrifugal pump. In Handbook of Powder Technology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2001; Volume 10, pp. 499–504. [Google Scholar]

- Chandel, S.; Singh, S.N.; Seshadri, V. A comparative study on the performance characteristics of centrifugal and progressive cavity slurry pumps with high concentration fly ash slurries. Part. Sci. Technol. 2011, 29, 378–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagalthivarthi, K.V.; Gupta, P.K.; Tyagi, V.; Ravi, M.R. CFD prediction of erosion wear in centrifugal slurry pumps for dilute slurry flows. J. Comput. Multiph. Flow 2011, 3, 225–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pegon, P. On the Lagrangian branched transport model and the equivalence with its Eulerian formulation. In Topological Optimization and Optimal Transport; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2017; pp. 281–303. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, A.; Law, W.K. Numerical modeling of municipal waste bed incineration. Int. J. Numer. Methods Heat Fluid Flow 2019, 29, 504–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biobaku, A.; Schmitz, W.; Naidoo, R. Wall roughness modification of a standard Lagrangian model for the prediction of saltation velocities in gas–solid flows. Energy 2019, 176, 888–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarodiya, R.; Gandhi, B.K. Numerical investigation of erosive wear of a centrifugal slurry pump due to solid–liquid flow. J. Tribol. 2021, 143, 101702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarodiya, R.; Gandhi, B.K. Experimental investigation of centrifugal slurry pump casing wear handling solid–liquid mixtures. Wear 2019, 434–435, 202972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, G.J.; Huang, X.; Zhou, L.; Zhou, G.X.; Zhou, H. Solid–liquid two-phase flow and wear analysis in a large-scale centrifugal slurry pump. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2020, 114, 104602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffery, P.K.; Godfrey, R.W.; Adelroth, E.; Nelson, F.; Rogers, A.; Johansson, S.A. Effects of treatment on airway inflammation and thickening of basement membrane reticular collagen in asthma: A quantitative light and electron microscopic study. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1992, 145, 890–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Wassgren, C.; Hancock, B.; Ketterhagen, W.; Curtis, J. Validation and time step determination of discrete element modeling of flexible fibers. Powder Technol. 2013, 249, 386–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musango, L.; John, S.; Lloyd, M. CFD–DEM simulation of small-scale challenge problem 1 with EMMS bubble-based structure-dependent drag coefficient. Particuology 2020, 55, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.H.; Yang, C.J.; Yan, C.S.; Chai, M.; Sun, Z.N. Study on fiber clogging mechanism in sewage pump based on CFD–DEM simulation. Energies 2022, 15, 1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.; Liu, H.Y.; Hu, D.; Liu, M.; Wang, S.; Zhao, W. Research on sediment wear characteristics of large axial-flow pump. Lubr. Eng. 2019, 44, 89–95. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.Y.; Wang, F.J.; Chen, W.H.; He, Q.R.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Z.C. A dynamic particle scale-driven interphase force model for water–sand two-phase flow in hydraulic machinery and systems. Int. J. Heat Fluid Flow 2022, 95, 108974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supraba, I.; Majid, A.I.; Pradecta, M.R.; Widyaparaga, A. Experimental investigation on the flow behavior during the solid particles lifting in a micro-bubble generator type airlift pump system. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2019, 13, 100386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perissinotto, R.M.; Verde, W.M.; Biazussi, J.L.; Bulgarelli, N.A.V.; Fonseca, W.D.P.; de Castro, M.S.; de Moraes Franklin, E.; Bannwart, A.C. Flow visualization in centrifugal pumps: A review of methods and experimental studies. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2021, 203, 108582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Shi, J.W.; Zhao, Q.Y.; Jin, H. Research progress of industrial application based on two-phase flow system of supercritical carbon dioxide and particles. Powder Technol. 2022, 407, 117621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Felice, R. The voidage function for fluid–particle interaction systems. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 1994, 20, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archard, J.F. Contact and Rubbing of Flat Surfaces. J. Appl. Phys. 1953, 24, 981–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imasaka, Y.; Kanno, H.; Saito, S.; Miyagawa, K.; Kawai, M. Clogging mechanisms of vortex pumps: Fibrous material motion capture and simulation with a CFD and DEM coupling method. In Proceedings of the ASME 2018 5th Joint US-European Fluids Engineering Division Summer Meeting, Montreal, QC, Canada, 15–20 July 2018; p. V003T12A030. [Google Scholar]

- Forgacs, O.L.; Mason, S.G. Particle Motions in Sheared Suspensions. IX. Spin and Deformation of Threadlike Particles. J. Colloid Sci. 1959, 14, 473–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desale, G.R.; Gandhi, B.K.; Jain, S.C. Effect of Erodent Properties on Erosion Wear of Ductile Type Materials. Wear 2006, 261, 914–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Flow rate (Q) | 25 m3/h |

| Head | 20 m |

| Rotation speed (n) | 2800 r/min |

| Efficiency (η) | 52% |

| Inlet diameter of the impeller (D1) | 70 mm |

| Outlet diameter of the impeller (D2) | 60 mm |

| Schemes | Mesh Number | Head (m) | Changing Value (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1325741 | 21.24 | |

| 2 | 1824378 | 21.11 | 1.57 |

| 3 | 2354012 | 21.03 | 0.68 |

| 4 | 3574628 | 20.89 | 0.23 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zheng, S.; Li, Y.; Wang, L.; Sun, Z.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, C. Effects of Short, Flexible Fibers on Clogging and Erosion in a Sewage Pump. Water 2026, 18, 114. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010114

Zheng S, Li Y, Wang L, Sun Z, Zhao X, Zhang C. Effects of Short, Flexible Fibers on Clogging and Erosion in a Sewage Pump. Water. 2026; 18(1):114. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010114

Chicago/Turabian StyleZheng, Shuihua, Yiliang Li, Liuming Wang, Zenan Sun, Xueyan Zhao, and Cheng Zhang. 2026. "Effects of Short, Flexible Fibers on Clogging and Erosion in a Sewage Pump" Water 18, no. 1: 114. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010114

APA StyleZheng, S., Li, Y., Wang, L., Sun, Z., Zhao, X., & Zhang, C. (2026). Effects of Short, Flexible Fibers on Clogging and Erosion in a Sewage Pump. Water, 18(1), 114. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010114