Leakage Modelling in Water Distribution Networks: A Novel Framework for Embedding FAVAD Formulation into EPANET 2.2

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Prevention of leakage backflow under both demand-driven and pressure-driven analyses (DDA and PDA);

- Keeping the original WDN topology without any addition of fictitious elements;

- Association of leaks with pipes rather than nodes, and providing leaks on pipes as an output;

- Flexibility of dealing with different leakage configurations;

- No alteration of the source code of EPANET 2.2.

2. Methodology

2.1. Basic Formulations

- The leakage exponent tends to 0.5 when the leakage number tends to 0. Evidently, the fact that NL approaches 0 means no leak area variation, so the leak outflow simply obeys the orifice equation.

- The increase in NL (i.e., the variable part of the leak area is increasing) is followed by an increase in the leak exponent, reaching a maximum value of 1.5.

2.2. Formatting FAVAD Under Power Law Expression

2.3. Algorithm for Implementation of the FAVAD Formulation Under EPANET 2.2

2.3.1. Main Steps

- Upload the network input file and define required parameters.

- Define a set of leaking pipes.

- Analyse the network under the assumption of a fixed leak area: k = 1. One run of EPANET is performed.

- Start a first loop through all the leaking pipes: in each of the end nodes of a leaking pipe i:

- Evaluate the parameters m (slope of area versus pressure curve) considering the obtained pressure in the node and the characteristics of the leaking pipe linked to that node (the pipe treated at the iteration i);

- Evaluate the emitter coefficient C as a function of the pressure in the node and the evaluated value of m;

- Set the two obtained values of C (one for each end node) as emitter coefficients for these nodes.

- After setting the new emitter coefficients for all the end nodes of the leaking pipes, analyse the network: k = k +1, another run of EPANET is performed.

- For all the nodes of the network, check the pressure difference between the iterations k and k − 1 and set a condition (a stop criterion for the algorithm), for example: condition: mean(|Pressure(j,k)−Pressure(j,k−1)|) < ε, with j and k being indices associated with nodes and iterations, respectively, whereas ε is the predefined tolerance.

- As long as the condition is not fulfilled, repeat steps 4 to 6, resetting the emitter coefficients to zero before looping over the leaking pipes.

- Once the condition is fulfilled, save the output results for all the nodes (head, pressure, emitter coefficient, total outflow, leakage outflow, …)

- For the pipes, evaluate the leakage from each pipe considering the leakage flow rate at its end nodes and its connection to other pipes, and save the results for all the pipes of the network (velocity, flow rate, leakage).

- Although evaluated at nodes, the leakage is associated with pipes, which is more physically based;

- To calculate the emitter coefficients, the pressure and the slope m are evaluated. In fact, m is not a constant parameter for all pipes, as it depends on the pipe characteristics. Furthermore, if spiral or circumferential crack shapes are considered, the parameter m also becomes pressure-dependent. Therefore, one of the advantages of the proposed algorithm is that it does not require linearization of head-area plots towards a constant value of m when dealing with spiral or circumferential cracks. In fact, m is updated based on the evaluated pressure at the nodes in each iteration.

- For the convergence of the algorithm, the iterative procedure is set to end once nodal pressure values for two consecutive iterations are quasi equal, i.e., the searched for emitter coefficient values are obtained (since they are pressure dependent). Accordingly, the stop criterion as defined in step 6 assumes that the convergence is reached once the mean value of the nodal pressure difference between the two last iterations (“k” and “k−1”) does not exceed the predefined tolerance ε. For instance, for the numerical tests carried out in this work, ε was set equal to 1 × 10−3 m (1 mm of pressure head).

- For outputs related to pipes, the algorithm allows for evaluating leakage from each pipe separately, including cases where nodes are shared by multiple leaking pipes.

2.3.2. Specific Configurations of Pipe Leakage

- A leaking pipe with a reservoir (or a tank) as one of the end nodes (1st configuration: Figure 1a: the reservoir (node n1) is one of the end nodes of the leaking pipe (pipe p1). In this case, the leakage rate is calculated through an emitter coefficient C evaluated only at node n2 (as indicated by the red arrow) using the expression given by Equation (10) and the slope m value calculated using Equation (7) depending on the leak shape.

- A leaking pipe with both end nodes as normal junctions (2nd configuration: Figure 1b: both end nodes n2 and n3 of the leaking pipe (pipe p2) are normal junctions. In this case, the emitter coefficient is evaluated for both node n2 and node n3 (as indicated by the red arrows in both sides of the leak), considering their respective pressure values and assuming that the crack area is divided evenly between the two sides of the pipe (the side linked to node n2 and the side linked to node n3). In fact, since it is possible to evaluate the leak on both sides of the pipe, it is assumed that the leak flow from each side of the pipe is the result of the contribution of half the length of the crack. It must be noted that, in practice, a pipe can accommodate a large number of narrow cracks (in the range of a few millimetres in length) randomly distributed along its length. For modelling purposes, all these narrow cracks are modelled as a single crack centred in the middle of the pipe, with a length equal to the sum of the lengths of the narrow elementary cracks and a width equal to their mean width. Since the network’s input file for EPANET 2.2 reports only the end nodes of each pipe and treats them as calculation points, the effect of the crack, i.e., the leakage outflow, is evaluated at the end nodes of the pipe, under the assumption that the crack is centred in the middle. It is worth noticing that assuming a centred crack and splitting its effect (the leakage) between the two end nodes of the pipe is not an equivalent representation of the narrow cracks’ effects due to the difference between local pressures (in elementary crack positions) and the end node pressures. Indeed, elementary leakage rates are not equal to both leakage rates evaluated in end nodes. If crack locations are known, embedding the FAVAD approach in EPANET would require adding as many dummy nodes as the number of cracks. This task, although possible to execute, necessitates altering the WDN’s input file, which would complicate the numerical model. Additionally, in most cases, precise leak locations are unknown. Then, to keep using EPANET without altering the network topology or EPANET’s source code, a way to proceed is to calibrate the lengths of the centred cracks to compensate for the errors in leakage evaluation induced by the difference in pressure values between end nodes and crack locations. Since the calibration of the crack length is not the scope of this work, as it requires field leakage data in hand, we assumed that the crack length Lc is an already calibrated length that compensates for the pressure effects.

- iii.

- An end node belonging to more than one leaking pipe (3rd configuration: Figure 1c): the node n3 is an end node of two adjacent leaking pipes (pipe p2 and pipe p3). Under this configuration, node n3 will appear as a calculation node for the emitter coefficient in two distinct loops i (once as an end node for pipe p2 and once as an end node for pipe p3). In this case, the resulting emitter coefficients from both loops are summed up to evaluate the emitter coefficient of node n3 (two red arrows are directed to node 3 from p2 and p3 as seen in Figure 1c).

3. Case Studies

4. Application and Results

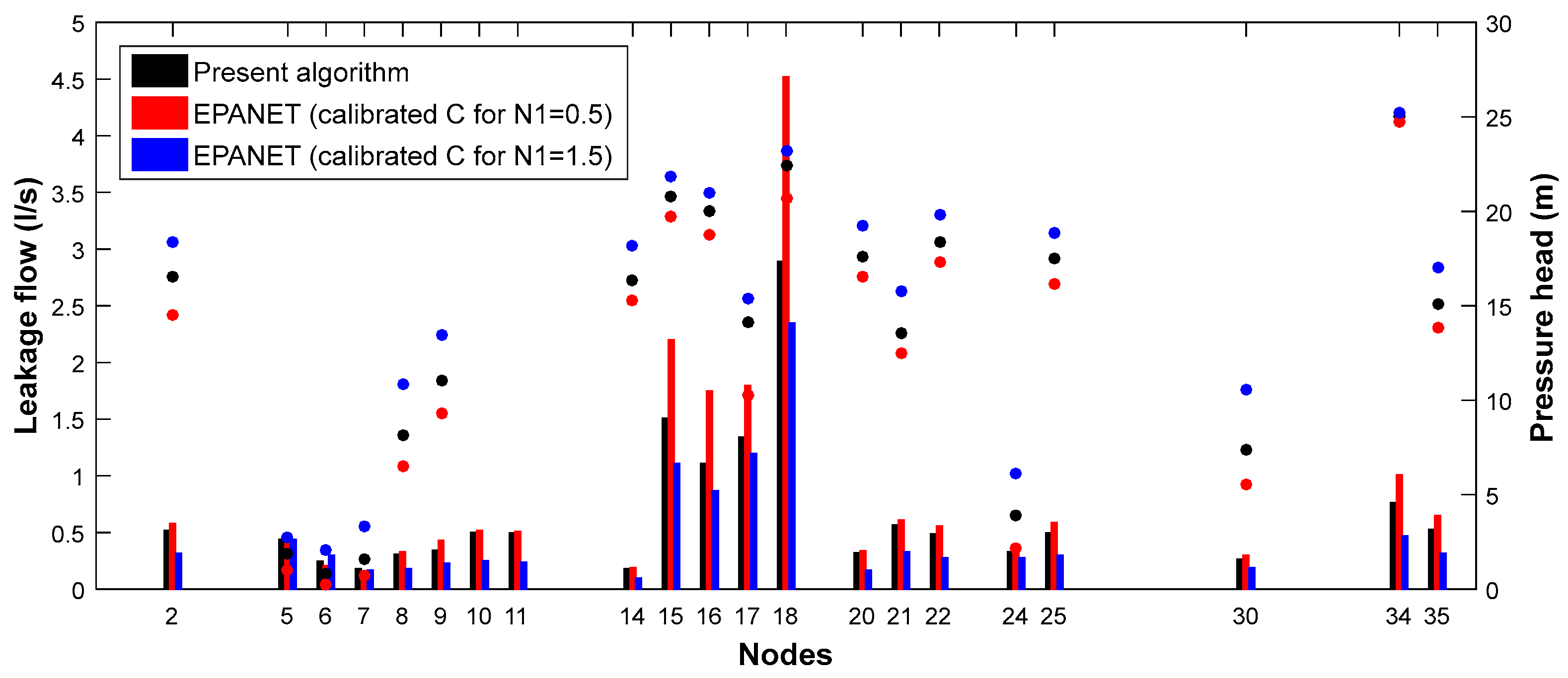

4.1. First Test: Present Algorithm vs. Calibrated EPANET 2.2

4.1.1. Calibration of Emitter Coefficients in EPANET 2.2

4.1.2. Testing of the Calibrated Emitter Coefficients Under a Reduced Service Pressure

4.1.3. Testing of the Calibrated Emitter Coefficients Under Highly Reduced Service Pressure

4.1.4. Evaluation of Leakage in Pipes

4.2. Second Test: FAVAD Approach vs. Fixed-Area Assumption

4.2.1. Effect of Pipe Material

- Under a fixed leaking area assumption (m = 0): by performing a direct analysis in EPANET 2.2 with setting and N1 = 0.5;

- Using the developed algorithm, considering the FAVAD approach in the case of HDPE pipes (E = 1 GPa);

- Using the developed algorithm, considering the FAVAD approach and assuming the pipes of Fossolo WDN to be made up of cast iron (E = 100 GPa).

4.2.2. Effect of the Crack Shape

4.3. Third Test: Large-Scale WDN Under PDA Approach

5. Conclusions

- The FAVAD approach can be successfully embedded into EPANET 2.2 following an iterative procedure without altering the WDN’s input file or EPANET’s source code;

- An iterative procedure in Matlab allows using the emitter function of EPANET 2.2 for leakage modelling while preventing leakage backflow in case of negative nodal pressure under both DDA and PDA demand models;

- Although evaluated in end nodes, through the iterative procedure, it is possible to associate leakage with pipes and to evaluate the leakage rate for each pipe in the EPANET environment;

- The use of the FAVAD approach becomes necessary in the case of modelling leakage in a highly elastic pipeline that accommodates longitudinal or spiral cracks.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DDA | Demand-driven analysis |

| FAVAD | Fixed and variable area discharge |

| HDPE | High-density polyethylene |

| LBB | Leak before burst |

| PDA | Pressure-driven analysis |

| WDN | Water distribution network |

References

- Lo Presti, J.; Giudicianni, C.; Toffanin, C.; Creaco, E.; Magni, L.; Galuppini, G. Combining clustering and regularized neural network for burst detection and localization and flow/pressure sensor placement in water distribution networks. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 63, 105473. [Google Scholar]

- Rathnayaka, S.; Shannon, B.; Zhang, C.; Kodikara, J. Introduction of the leak-before-break (LBB) concept for cast iron water pipes on the basis of laboratory experiments. Urban Water J. 2017, 14, 820–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupiper, A.; Weill, J.; Bruno, E.; Jessoe, K.; Loge, F. Untapped potential: Leak reduction is the most cost-effective urban water management tool. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 034021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latchoomun, L.; Mawooa, D.; Ah King, R.T.F.; Busawon, K.; Binns, R. Quantifying the Pumping Energy Loss Associated with Different Types of Leak in a Piping System. In Emerging Trends in Electrical, Electronic and Communications Engineering; ELECOM 2016. Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering; Fleming, P., Vyas, N., Sanei, S., Deb, K., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altowayti, W.A.H.; Othman, N.; Tajarudin, H.A.; Al-Dhaqm, A.; Asharuddin, S.M.; Al-Gheethi, A.; Alshalif, A.F.; Salem, A.A.; Din, M.F.M.; Fitriani, N.; et al. Evaluating the Pressure and Loss Behavior in Water Pipes Using Smart Mathematical Modelling. Water 2021, 13, 3500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anfinsen, H.; Aamo, O.M. Leak detection, size estimation and localization in branched pipe flows. Automatica 2022, 140, 110213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelmsen, N.C.A.; Aamo, O.M. Leak Detection, Size Estimation and Localization in Water Distribution Networks Containing Loops. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 61st Conference on Decision and Control (CDC), Cancun, Mexico, 6–9 December 2022; pp. 5429–5436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, D.; Zanfei, A.; Menapace, A.; Meirelles, G.; Herrera, M.; Brentan, B. Leak detection and localization in water distribution systems via multilayer networks. Water Res. X 2025, 26, 100280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, S.B.; Curren, M.D.; Sims, N.D.; Stanway, R. Pipeline network features and leak detection by cross-correlation analysis of reflected waves. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2015, 131, 715–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elandalibe, K.; Jbari, A.; Bourouhou, A. Application of cross-correlation technique for multi leakage detection. In Proceedings of the 2015 Third World Conference on Complex Systems (WCCS), Marrakech, Morocco, 23–25 November 2015; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Brennan, M.J.; Liu, Y.; Almeida, F.C.L.; Joseph, P.F. Improving the shape of the cross-correlation function for leak detection in a plastic water distribution pipe using acoustic signals. Appl. Acoust. 2017, 127, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicola, M.; Nicola, C.I.; Vintilă, A.; Hurezeanu, I.; Duță, M. Pipeline Leakage Detection by Means of Acoustic Emission Technique Using Cross-Correlation Function. J. Mech. Eng. Autom. 2018, 8, 59–67. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, P.J.; Vítkovský, J.P.; Lambert, M.F.; Simpson, A.R.; James, A. Frequency Domain Analysis for Detecting Pipeline Leaks. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2005, 131, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lay-Ekuakille, A.; Vergallo, P.; Trotta, A. Impedance Method for Leak Detection in Zigzag Pipelines. Meas. Sci. Rev. 2010, 10, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. Time-domain impedance method for transient analysis and leakage detection in reservoir pipeline valve systems. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2022, 167, 108527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kim, B. Machine learning model for leak detection using water pipeline vibration sensor. Sensors 2023, 23, 8935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajasekaran, U.; Kothandaraman, M.; Hong Pua, C. Water pipeline leak detection and localization with an integrated AI technique. IEEE Access 2024, 13, 2736–2745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wu, X.; Jiang, Z.; Li, Q.; Zhang, L.; Chu, J.; Song, Y.; Yang, L. Application of machine learning to leakage detection of fluid pipelines in recent years: A review and prospect. Measurement 2025, 248, 116857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, D.; Blesa, J.; Duviella, E.; Rajaoarisoa, L. Leak Detection in Water Distribution Networks Based on Water Demand Analysis. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2022, 55, 679–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.S.; Lee, H.-H.; Lee, Y.-J. Prediction of Minimum Night Flow for Enhancing Leakage Detection Capabilities in Water Distribution Networks. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 6467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zhang, J.; Xiong, J. Leakage assessment of water supply networks in a university based on WB-Easy Calc and night minimum flow: A case study in Xi’an. Water Supply 2024, 24, 2781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giudicianni, C.; Mazzoni, F.; Marsili, V.; Alvisi, S.; Creaco, E. Modelling minimum night consumption as a function of long-run average outflow to users and applications to real world case studies. Front. Water 2025, 7, 1693893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzolani, G.; Berardi, L.; Laucelli, D.; Martino, R.; Simone, A.; Giustolisi, O. A Methodology to Estimate Leakages in Water Distribution Networks Based on Inlet Flow Data Analysis. Procedia Eng. 2016, 162, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizarraga-Raygoza, A.; Delgado-Aguiñaga, J.A.; Begovich, O. Steady state algorithm for leak diagnosis in water pipeline systems. IFAC Pap. 2018, 51, 402–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucciarelli, T.; Criminisi, A.; Termini, D. Leak analysis in pipeline system by means of optimal value regulation. J. Hydraul. Eng. 1999, 125, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, J. Pressure Dependent Leakage; World Water and Environmental Engineering, Water Environment Federation: Washington, DC, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Piller, O.; van Zyl, J.E. Incorporating the FAVAD Leakage Equation into Water Distribution System Analysis. Procedia Eng. 2014, 89, 613–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creaco, E. Global algorithm based on inverse outflow/head relationship for solving water distribution networks with multiple nodal outflows and improved convergence. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 2025, 151, 04025017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossman, L.A.; Woo, H.; Tryby, M.; Shang, F.; Janke, R.; Haxton, T. EPANET 2.2 User’s Manual; Water Infrastructure Division, Center for Environmental Solutions and Emergency Response, Office of Research and Development, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Cincinnati, OH, USA, 2020.

- Muranho, J.; Ferreira, A.; Sousa, J.; Gomes, A.; Sá Marques, A. Pressure–dependent Demand and Leakage Modelling with an EPANET Extension—WaterNetGen. Procedia Eng. 2014, 89, 632–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, H.; Nie, L. Hydraulic Simulation of Water Supply Network Leakage Based on EPANET. J. Pipeline Syst. Eng. Pract. 2023, 15, 05023006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaydalani, M.O. Hydraulic modelling for leakage reduction in water distribution systems through pressure control. Open Civ. Eng. J. 2024, 18, E18741495289971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demetrios, G.E.; Marios, K.; Stelios, V.; Marios, M.P. EPANET-MATLAB Toolkit: An Open-Source Software for Interfacing EPANET with MATLAB. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Computing and Control for the Water Industry (CCWI), Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 7–9 November 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grevenstein, B.; van Zyl, J.E. An experimental investigation into the pressure-leakage relationship of some failed water pipes. J. Water Supply Res. Technol.—AQUA 2007, 56, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrante, M. Experimental investigation of the effects of pipe material on the leak head discharge relationship. J. Hydraul. Eng. ASCE 2012, 138, 736–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassa, A.M.; van Zyl, J.E. Predicting the head-leakage slope of cracks in pipes subject to elastic deformations. J. Water Supply Res. Technol.-AQUA 2013, 62, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassa, A.M.; van Zyl, J.E. Predicting the leakage exponents of elastically deforming cracks in pipes. Procedia Eng. 2014, 70, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deyi, M.; van Zyl, J.; Shepherd, M. Applying the FAVAD Concept and Leakage Number to Real Networks: A Case Study in Kwadabeka, South Africa. Procedia Eng. 2014, 89, 1537–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzola, I.; Alvisi, S.; Franchini, M. Analysis of MNF and FAVAD Model for Leakage Characterization by Exploiting Smart-Metered Data: The Case of the Gorino Ferrarese (FE-Italy) District. Water 2021, 13, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafeim, A.V.; Fourniotis, N.T.; Deidda, R.; Kokosalakis, G.; Langousis, A. Leakages in water distribution networks: Estimation methods, influential factors, and mitigation strategies—A comprehensive review. Water 2024, 16, 1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gere, J.M. Mechanics of Materials, 5th ed.; Brooks/Cole: Pacific Grove, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Creaco, E.; Franchini, M. Low level hybrid procedure for the multi-objective design of water distribution networks. Procedia Eng. 2014, 70, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdi, J.; Choi, Y.H.; Kim, J.H. Non-dominated sorting harmony search differential evolution (NS-HS-DE): A hybrid algorithm for multi-objective design of water distribution networks. Water 2017, 9, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santonastaso, G.F.; Di Nardo, A.; Di Natale, M.; Giudicianni, C.; Greco, R. Scaling-laws of flow entropy with topological metrics of water distribution networks. Entropy 2018, 20, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonora, M.A.; Capano, G.; De Rango, A.; Maiolo, M. Novel Eulerian approach with cellular automata modelling to estimate water quality in a drinking water network. Water Resour. Manag. 2022, 36, 5961–5976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artina, S.; Bolognesi, A.; Bragalli, C.; D’ambrosio, C.; Marchi, A. Comparison among best solutions of the optimal design of water distribution networks obtained with different algorithms. In CCWI 2011 Urban Water Management: Challenges and Opportunities; Centre for Water Systems: Exeter, UK, 2011; Volume 3, pp. 985–990. [Google Scholar]

- Herrera, M.; Giudicianni, C.; Sasidharan, M.; Wright, R.; Creaco, E.; Parlikad, A.K. Landmark-node based reliability assessment for critical infrastructure networks. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2025, 265, 111563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, M.; Gong, J.; Zhang, C.; Marchi, A.; Dix, L.; Lambert, M.F. Leak-Before-Break Main Failure Prevention for Water Distribution Pipes Using Acoustic Smart Water Technologies: Case Study in Adelaide. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 2020, 146, 05020020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, J.M.; Shamir, U.; Marks, D.H. Water distribution reliability: Simulation method. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 1988, 114, 276–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Tests | Objective | Network | Demand Model | Settings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First test | - Calibration of emitter coefficients in EPANET 2.2 | Fossolo | DDA | - Default settings |

| - Testing the stability of the calibration | Fossolo | DDA | - Reduced service pressure (reservoir level lowered to 91 m) | |

| - Preventing the emitter backflow | Fossolo | DDA | - Highly reduced service pressure (reservoir level lowered to 71 m) | |

| Second test | - Effect of crack shape | Fossolo | DDA | - Different crack shapes (longitudinal, spiral and circumferential) |

| - Effect of pipe material | Fossolo | DDA | - Two different pipe materials (HDPE and cast iron) | |

| Third test | - Scalability of the algorithm and preventing the emitter backflow under PDA | Modena | DDA and PDA | - Reduced service pressure (reservoir levels lowered by 35 m each); PDA with hmin = 5 m; hreq = 10 m and n = 0.5 |

| Parameter | Fossolo WDN | Modena WDN |

|---|---|---|

| Young modulus E (GPa) | 1 (HDPE) | 100 (cast iron) |

| Pipe wall thickness t (mm) | 0.1D (with D (mm) is the pipe diameter) | 4.57 (for D = 100; 125; 150 mm) 5.84 (for D = 200 mm) 7.11 (for D = 250; 300 mm) 7.87 (for D = 350; 400 mm) |

| Crack length per unit of pipe length lc (mm/m) | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Crack width Wc (mm) | 1 | 1 |

| Pipe | Node n1 | Node n2 | Pipe | Node n1 | Node n2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 5 | 6 | 36 | 15 | 16 |

| 8 | 7 | 24 | 39 | 30 | 9 |

| 16 | 10 | 11 | 40 | 17 | 18 |

| 20 | 2 | 18 | 43 | 14 | 21 |

| 26 | 25 | 8 | 45 | 21 | 22 |

| 35 | 20 | 15 | 55 | 34 | 35 |

| Pipe | Node n1 | Node n2 | Pipe | Node n1 | Node n2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 28 | 53 | 230 | 94 | 118 | 117 |

| 44 | 76 | 217 | 237 | 15 | 213 |

| Node | C (ls−1m−0.5) | Pressure Head (m) | Leakage Flow (L/s) | Node | C (ls−1m−0.5) | Pressure Head (m) | Leakage Flow (L/s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 0.1532 | 38.07 | 0.94 | 17 | 0.5594 | 28.20 | 2.97 |

| 5 | 0.4560 | 4.76 | 0.99 | 18 | 0.9926 | 47.03 | 6.80 |

| 6 | 0.4383 | 4.39 | 0.92 | 20 | 0.0825 | 40.71 | 0.52 |

| 7 | 0.1930 | 6.86 | 0.50 | 21 | 0.1733 | 32.55 | 0.99 |

| 8 | 0.1283 | 25.48 | 0.64 | 22 | 0.1343 | 41.85 | 0.87 |

| 9 | 0.1400 | 30.07 | 0.77 | 24 | 0.2511 | 13.57 | 0.92 |

| 10 | 0.1051 | 53.39 | 0.77 | 25 | 0.1460 | 40.37 | 0.92 |

| 11 | 0.1050 | 52.11 | 0.75 | 30 | 0.1258 | 22.63 | 0.60 |

| 14 | 0.0477 | 38.48 | 0.30 | 34 | 0.2024 | 54.13 | 1.49 |

| 15 | 0.4954 | 45.69 | 3.35 | 35 | 0.1746 | 37.86 | 1.07 |

| 16 | 0.4040 | 44.50 | 2.70 | Leakage rate | 46.8% | ||

| Node | C (ls−1m−N1) | Node | C (ls−1m−N1) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N1 = 0.5 | N1 = 1.5 | N1 = 0.5 | N1 = 1.5 | ||

| 2 | 0.1532 | 0.0040 | 17 | 0.5594 | 0.0198 |

| 5 | 0.4560 | 0.0957 | 18 | 0.9926 | 0.0211 |

| 6 | 0.4383 | 0.0997 | 20 | 0.0825 | 0.0020 |

| 7 | 0.1930 | 0.0281 | 21 | 0.1733 | 0.0053 |

| 8 | 0.1283 | 0.0050 | 22 | 0.1343 | 0.0032 |

| 9 | 0.1400 | 0.0046 | 24 | 0.2511 | 0.0185 |

| 10 | 0.1051 | 0.0019 | 25 | 0.1460 | 0.0036 |

| 11 | 0.1050 | 0.0020 | 30 | 0.1258 | 0.0055 |

| 14 | 0.0477 | 0.0012 | 34 | 0.2024 | 0.0037 |

| 15 | 0.4954 | 0.0108 | 35 | 0.1746 | 0.0046 |

| 16 | 0.4040 | 0.0090 | |||

| Node | C (ls−1m−0.5) | Node | C (ls−1m−0.5) | Node | C (ls−1m−0.5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 0.1278 | 11 | 0.1010 | 21 | 0.1547 |

| 5 | 0.3179 | 14 | 0.0452 | 22 | 0.1140 |

| 6 | 0.2660 | 15 | 0.3308 | 24 | 0.1675 |

| 7 | 0.1471 | 16 | 0.2486 | 25 | 0.1188 |

| 8 | 0.1077 | 17 | 0.3579 | 30 | 0.0966 |

| 9 | 0.1035 | 18 | 0.6112 | 34 | 0.1527 |

| 10 | 0.1011 | 20 | 0.0767 | 35 | 0.1358 |

| Node | C (ls−1m−0.5) | Node | C (ls−1m−0.5) | Node | C (ls−1m−0.5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 0.1096 | 11 | 0.0984 | 21 | 0.1414 |

| 5 | 0 | 14 | 0.0434 | 22 | 0.0998 |

| 6 | 0 | 15 | 0.2169 | 24 | 0 |

| 7 | 0 | 16 | 0.1387 | 25 | 0.2088 |

| 8 | 0 | 17 | 0.174 | 30 | 0 |

| 9 | 0 | 18 | 0.3363 | 34 | 0.3113 |

| 10 | 0.0984 | 20 | 0.0728 | 35 | 0 |

| HDPE Pipes E = 1 GPa; HW = 150 | Cast Iron E = 100 GPa; HW = 130 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed Area | FAVAD | Fixed Area | FAVAD | |

| Number of iterations | 1 | 35 | 1 | 3 |

| Leakage rate | 32.28% | 46.80% | 31.05% | 31.30% |

| Relative error of leakage rate | 30.44% | 0.80% | ||

| Fixed Area | FAVAD | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Longitudinal Crack | Spiral Crack | Circumferential Crack | ||

| Number of iterations | 1 | 35 | 31 | 4 |

| Leakage rate | 32.28% | 46.80% | 44.85% | 33.66% |

| Relative error with reference to the fixed-area assumption | 0% | 30.44% | 28.02% | 4.10% |

| Node ID | Elevation (m) | DDA | PDA | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Head (m) | Pressure Head (m) | C (ls−1m−0.5) | Leakage Flow (L/s) | Head (m) | Pressure Head (m) | C (ls−1m−0.5) | Leakage Flow (L/s) | ||

| 15 | 41.26 | 29.49 | −11.76 | 0 | 0 | 38.06 | −3.19 | 0 | 0 |

| 53 | 39.28 | 25.52 | −13.75 | 0 | 0 | 37.98 | −1.29 | 0 | 0 |

| 76 | 41.09 | 28.25 | −12.83 | 0 | 0 | 38.00 | −3.08 | 0 | 0 |

| 117 | 30.59 | 25.11 | −5.47 | 0 | 0 | 36.36 | 5.77 | 0.077478 | 0.186 |

| 118 | 30.73 | 25.13 | −5.59 | 0 | 0 | 36.39 | 5.66 | 0.077477 | 0.184 |

| 213 | 37.3 | 29.54 | −7.75 | 0 | 0 | 38.09 | 0.79 | 0.434397 | 0.388 |

| 217 | 41.16 | 27.92 | −13.23 | 0 | 0 | 38.00 | −3.15 | 0 | 0 |

| 230 | 38.49 | 25.53 | −12.95 | 0 | 0 | 38.01 | −0.47 | 0 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hafsi, Z.; Giudicianni, C.; Creaco, E. Leakage Modelling in Water Distribution Networks: A Novel Framework for Embedding FAVAD Formulation into EPANET 2.2. Water 2026, 18, 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010100

Hafsi Z, Giudicianni C, Creaco E. Leakage Modelling in Water Distribution Networks: A Novel Framework for Embedding FAVAD Formulation into EPANET 2.2. Water. 2026; 18(1):100. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010100

Chicago/Turabian StyleHafsi, Zahreddine, Carlo Giudicianni, and Enrico Creaco. 2026. "Leakage Modelling in Water Distribution Networks: A Novel Framework for Embedding FAVAD Formulation into EPANET 2.2" Water 18, no. 1: 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010100

APA StyleHafsi, Z., Giudicianni, C., & Creaco, E. (2026). Leakage Modelling in Water Distribution Networks: A Novel Framework for Embedding FAVAD Formulation into EPANET 2.2. Water, 18(1), 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010100