Multi-Scale Experiments and Mechanistic Insights into Hydro-Physical Properties of Saturated Deep-Sea Sediments in the South China Sea

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

2.2. Hydro-Physical Properties and Mechanical Tests

2.3. Microstructural Testing

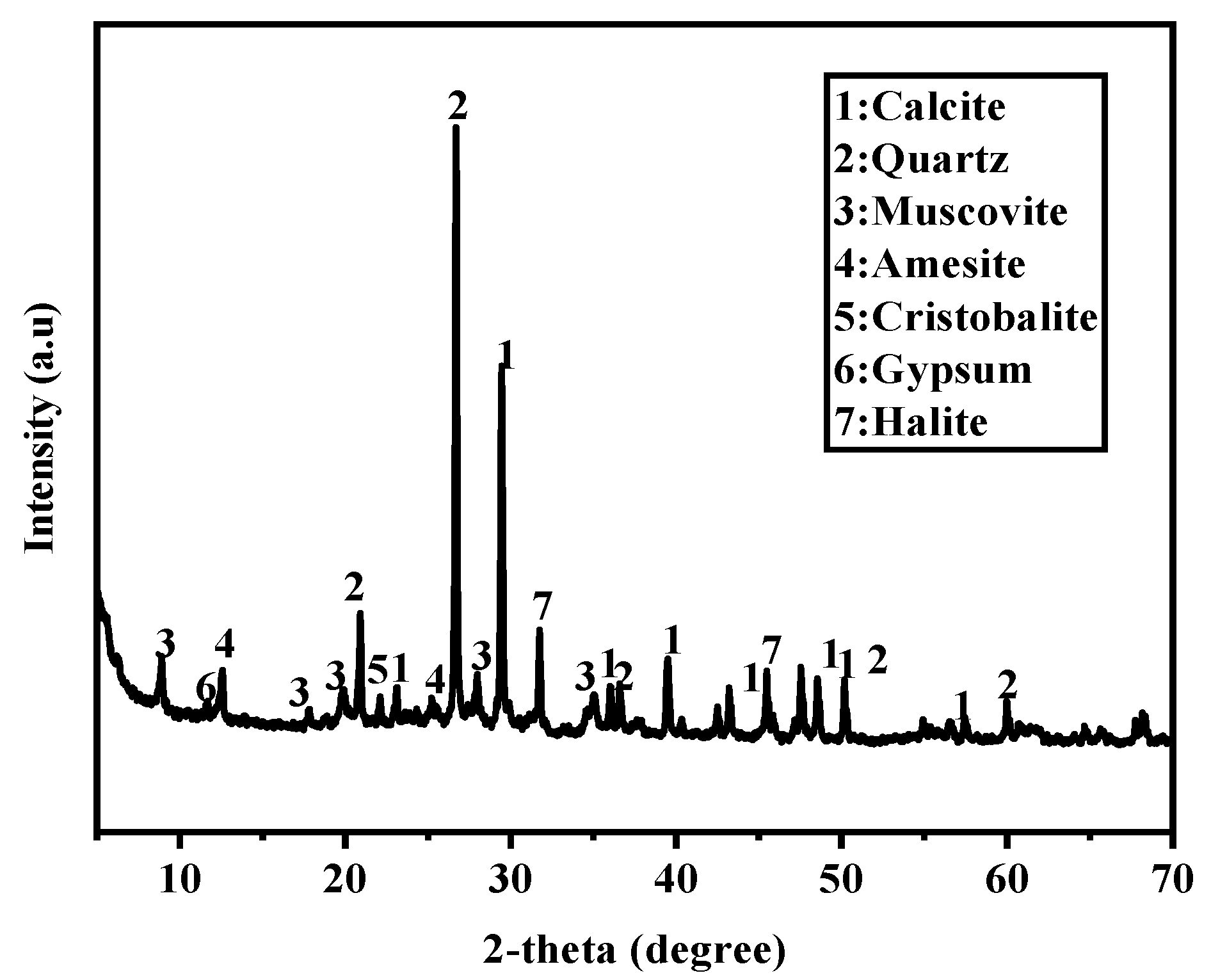

2.4. X-Ray Diffraction Test

2.5. EDX Energy-Dispersive Spectroscopy

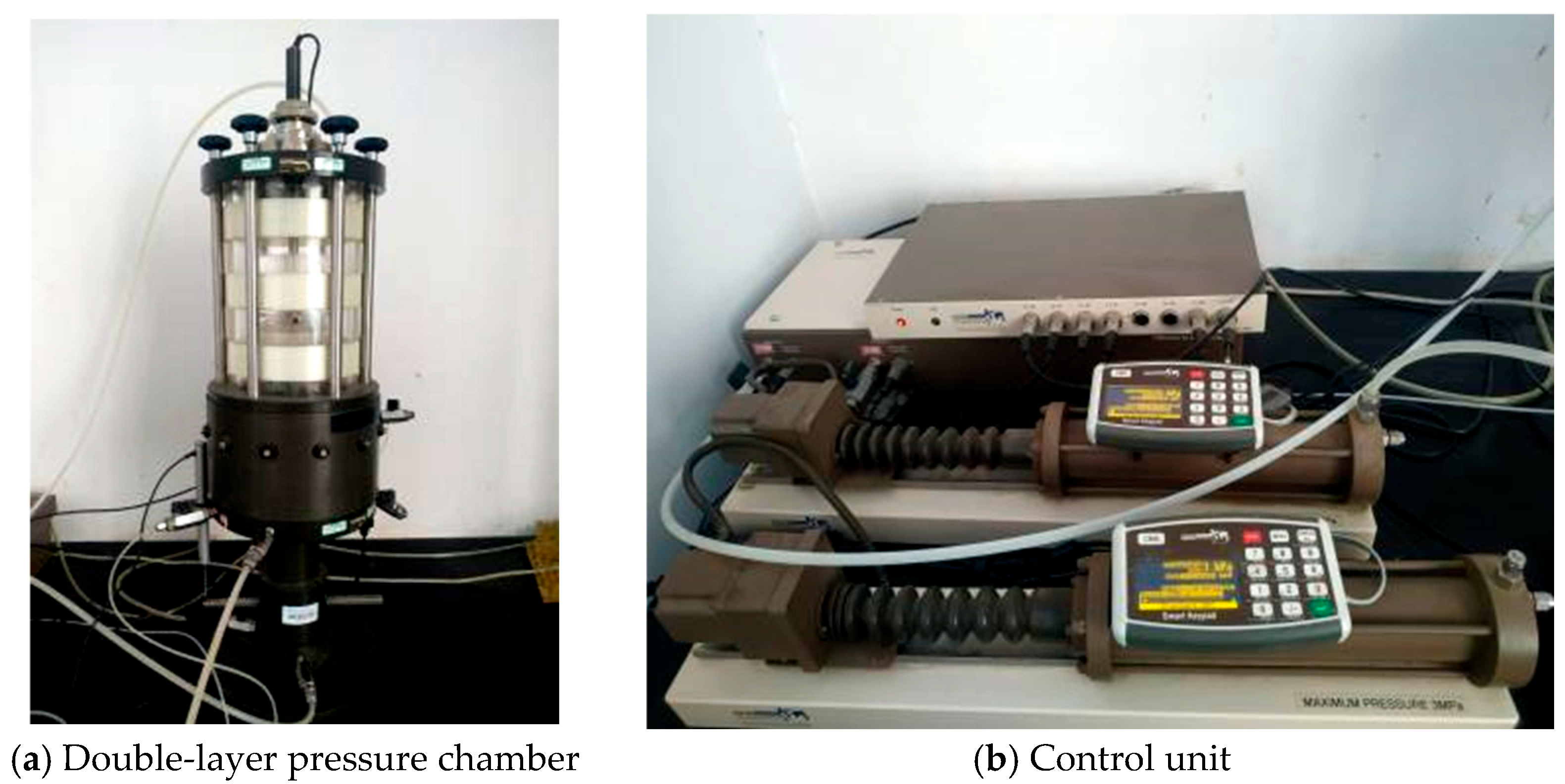

2.6. Triaxial Shear Test

2.7. One-Dimensional Consolidation Compression Test

3. Results

3.1. Basic Physical and Mechanical Properties

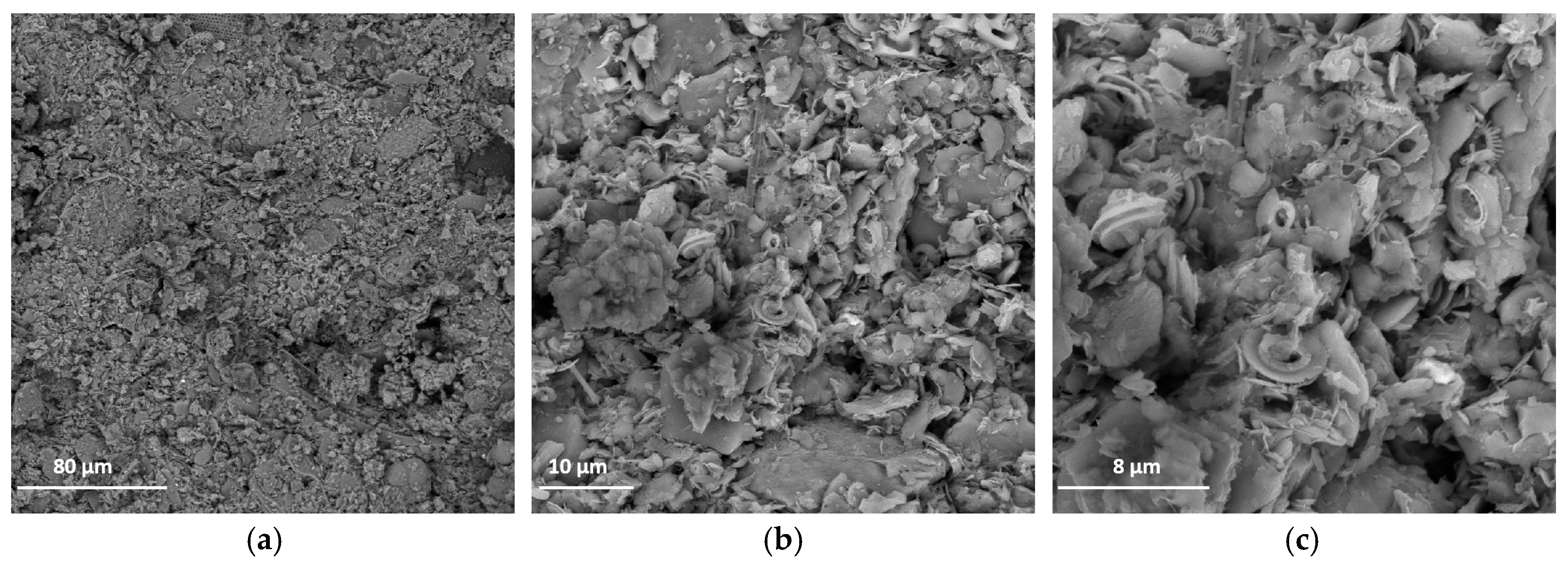

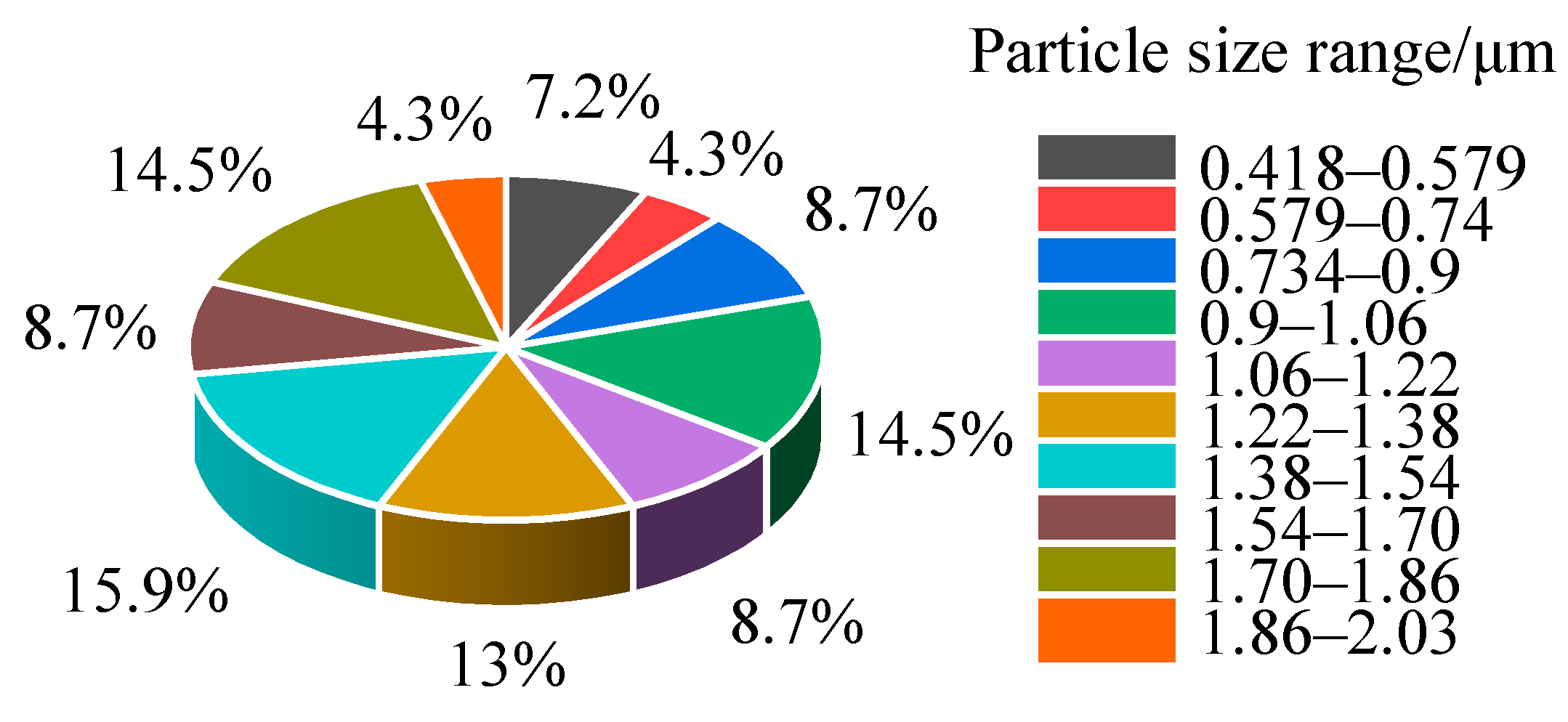

3.2. Results of the Microstructural Experiment

3.3. X-Ray Diffraction Analysis

3.4. EDX Energy Spectrum Analysis

3.5. Results of the Triaxial Shear Test

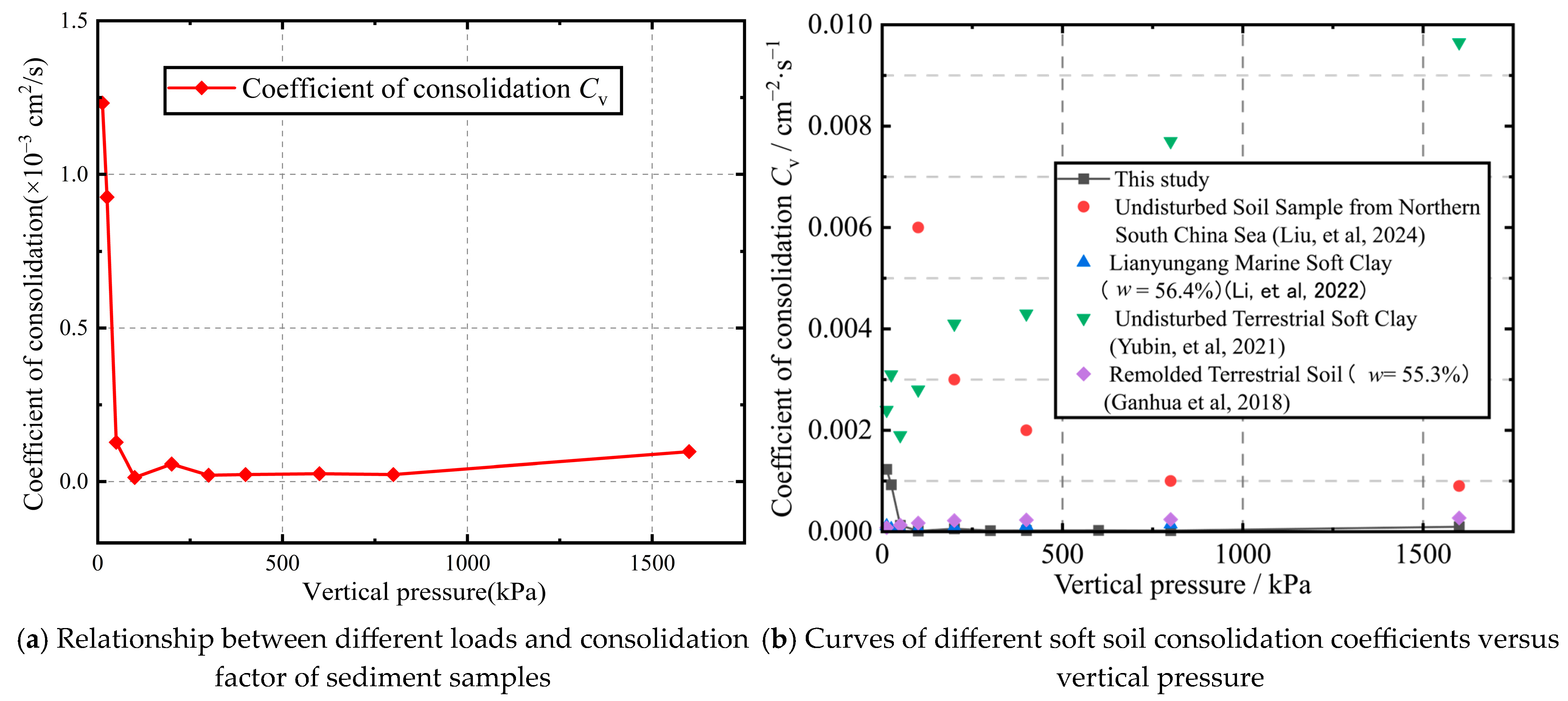

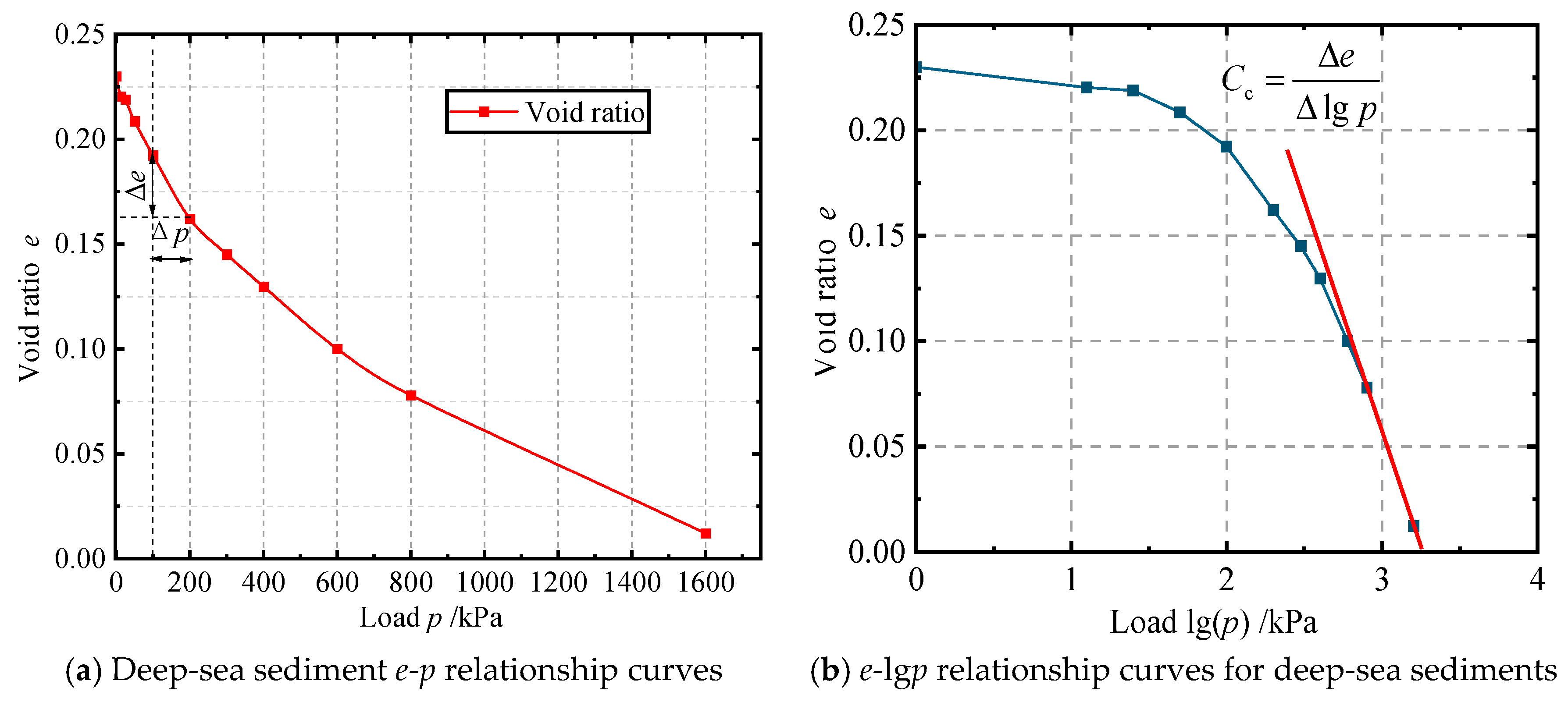

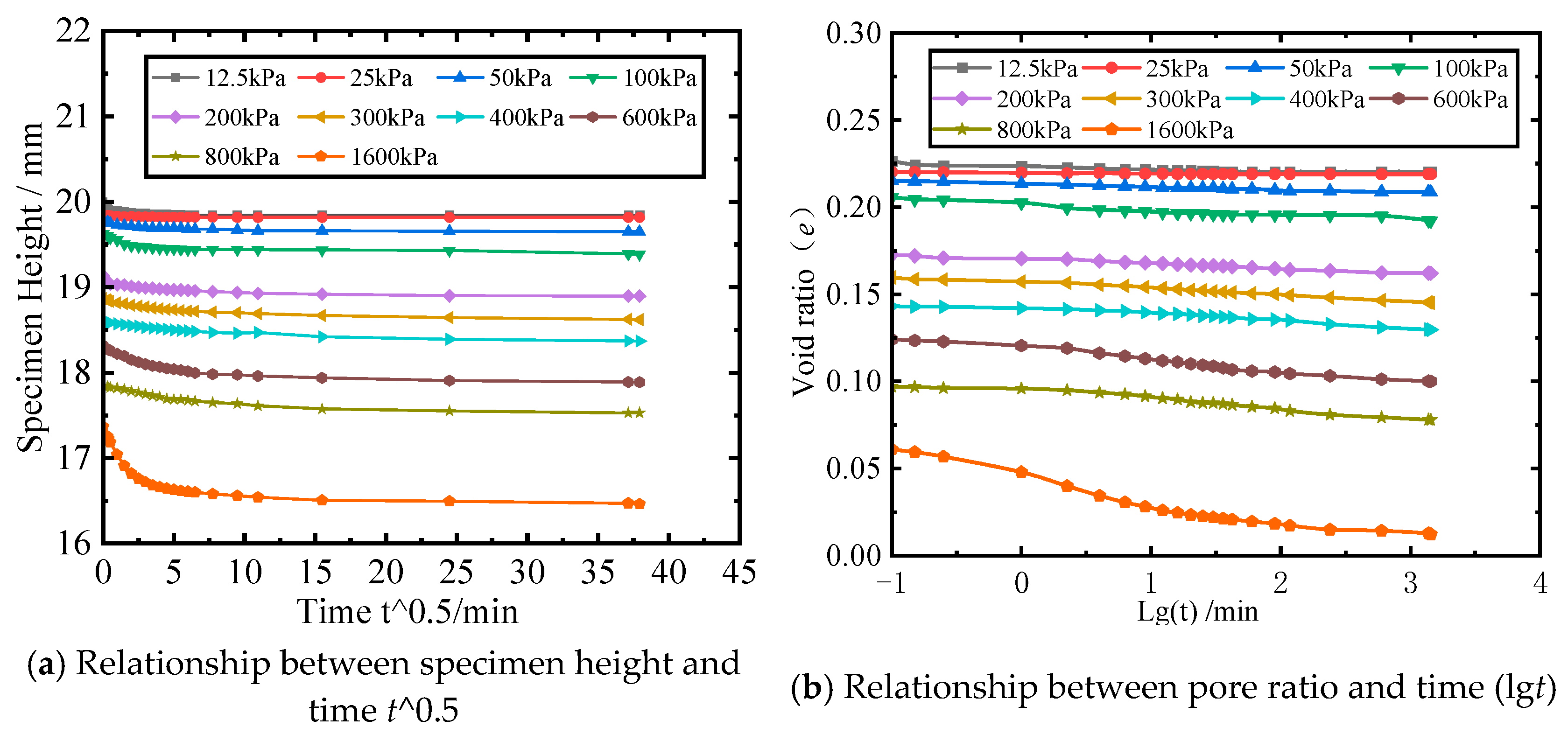

3.6. Results of One-Dimensional Consolidation Tests

4. Discussion

4.1. Geological Background’s Influence on Sediment Characteristics

4.2. Rationality of Experimental Method and Reliability Analysis of the Results

4.2.1. Basis for Selecting Reshaped Sediment Samples

4.2.2. Mechanism Linking Microstructure to Macroscopic Mechanical Behavior

4.2.3. Differences with Other Deep-Sea Sediments

4.3. Microscopic Mechanism Analysis of Mechanical Properties of the Deep-Sea Sediments

4.3.1. Granular Scale Mechanism of the Shear–Thrust to Shear–Shrink Transition

4.3.2. Consolidation Characteristics: Pore Water–Mineral Interactions

4.4. Engineering Application Value and Limitations

4.4.1. Practical Engineering Guidance Significance

4.4.2. Limitations of the Study

- Expand the spatiotemporal representativeness of samples to enhance the authenticity and regional applicability of experimental sediment samples. This can be achieved by establishing sampling points across different sedimentary units and water-depth gradients in the South China Sea and systematically collecting undisturbed sediment samples to improve the spatial generalizability of research conclusions.

- Strengthen the research on the dynamic load response mechanism, reveal the laws of strength deterioration and stability in engineering scenarios, conduct various types of dynamic load tests, and simulate deep-sea engineering load scenarios.

- Conduct long-term rheological property research, design triaxial creep tests, and simulate the long-term load conditions of deep-sea engineering.

5. Conclusions

- The deep-sea sediment has high water content, low density and high porosity, which belongs to the high liquid limit clay. It is mainly composed of clay minerals, silt particles, microbial debris and biological remains. The sediment is predominantly composed of muscovite, quartz, and calcite.

- Consolidated undrained (CU) tests yielded the total strength parameters of cohesion (c = 22.77 kPa) and the internal friction angle (φ = 11.02°), with effective strength parameters of c′ = 19.58 kPa and φ′ = 27.32°. During CU triaxial testing, the sediment initially exhibited dilative behavior upon shearing, transitioning to contractive behavior with continued deformation until a critical state was reached. Under various confining pressures, deviator stress exhibited strain-hardening characteristics, initially increasing and then stabilizing with principal strain ε1 development.

- One-dimensional consolidation tests indicated relatively small overall deformation under loading. The specimens showed negligible deformation and short primary consolidation duration under low-stress levels. When vertical pressure exceeded structural yield stress, significant deformation occurred. Classified as moderately compressible soil, this sediment’s consolidation coefficient exhibited an initial decrease followed by a gradual increase with loading, while the secondary consolidation coefficient showed a marked increase and then stabilization with vertical pressure elevation, and finally decreases slightly. Compared with other soft soils, both the consolidation and secondary consolidation coefficients of this deep-sea sediment displayed lower values.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aguzzi, J.; Chatzievangelou, D.; Marini, S.; Fanelli, E.; Danovaro, R.; Flögel, S.; Lebris, N.; Juanes, F.; De Leo, F.C.; Del Rio, J.; et al. New High-Tech Flexible Networks for the Monitoring of Deep-Sea Ecosystems. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 6616–6631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamil, M.; Siddiqui, N.A.; Usman, M.; Wahid, A.; Umar, M.; Ahmed, N.; Ul Haq, I.; El-Ghali, M.A.K.; Imran, O.S.; Rahman, A.H.A.; et al. Facies analysis and distribution of Late Palaeogene deep-water massive sandstones in submarine-fan lobes, NW Borneo. Geol. J. 2022, 57, 4489–4507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Liu, Z.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, C.; Ai, S.; Li, J.; Wang, X. Research on aquatic microcosm: Bibliometric analysis, toxicity comparison and model prediction. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 469, 134078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diesing, M. Deep-sea sediments of the global ocean. Earth Syst. Sci. Data Discuss. 2020, 2020, 3367–3381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.; He, S.; Chen, F.; Liao, Z.; Wang, J.; Deng, X. Engineering geological characteristics and genesisof the sediments from the southern Mariana Trench. J. Geol. 2015, 39, 251–257. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, M.J.; Li, Z.Y.; Huang, H.P.; Liu, J. Experimental study on microstructure and mechanical properties ofseabed soft soil from South China Sea. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2017, 39, 17–20. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, M.J.; Liu, A.S.; Li, G.S. Macro- and micro-characteristics and mechanical properties of deep-seasediment from South China Sea. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2023, 45, 618–626. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, A.; Kwok, C.; Li, W.; Jiang, M. Strain rate effects on intact deep-sea sediments under different confining pressures and overconsolidation ratios. Eng. Geol. 2023, 327, 107357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Long, J.J.; Li, G.X. Experimental study on mechanical propertiesof seafloor sediments of deep South China Sea. Ocean Eng. 2015, 33, 108–114. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Kechao, Z.; Xuan, Z.; Yanli, C.; Li, Y.; WenBo, M. Rheological properties of REY-rich deepsea sediments. Rock Soil Mech. 2022, 43, 348–356. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yubin, R.; Qing, Y.; Yin, W.; Shaoli, Y. Experimental study on thixotropic characteristic and microstructural evolution of representative deep-sea soft clay. J. Eng. Geol. 2021, 29, 1295–1302. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.; Lin, Y.; Qi, F.; Xu, J. Characterizing the sediment dynamics through in-situ measurements in the abyssal Manila Trench, northeast South China Sea. Mar. Geol. 2024, 476, 107372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, H.; Guo, X.; Fan, N.; Wu, H.; Nian, T. An undrained dynamic strain-pore pressure model for deep-water soft clays from the South China Sea. Front. Mar. Sci. 2024, 11, 1377474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.L.; Duan, G.-J.; Li, H.-L.; Zhao, F.-C. Dynamic shear modulus and damping ratio of deep-sea ultra-soft soil. Rock Soil Mech. 2023, 44, 3261–3271. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Sun, A.; Ren, Y.; Yang, G.; Yu, L.; Kong, G.; Wang, N.; Yang, Q. Ultrahigh static pore pressure effects on the undrained shear behavior of deep-sea cohesive soil. Appl. Ocean Res. 2023, 130, 103404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, S.; Duan, G. Steady rheological behavior and unified strength model for reconstituted deep-sea sediments. Eng. Geol. 2023, 316, 107058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, Q.A.; Sørlie, E.; Grimstad, G.; Eiksund, G.; Takahashi, H.; Sassa, S. Influence of sediment permeability in seismic-induced submarine landslide mechanism: CFD-MPM validation with centrifuge tests and analysis. Comput. Geotech. 2024, 174, 106588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Chen, X.; Wei, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, W.; Li, H. Experimental investigation of the inhibition of deep-sea mining sediment plumes by polyaluminum chloride. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2024, 34, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazis, I.-Z.; de Stigter, H.; Mohrmann, J.; Heger, K.; Diaz, M.; Gillard, B.; Baeye, M.; Veloso-Alarcón, M.E.; Purkiani, K.; Haeckel, M.; et al. Monitoring benthic plumes, sediment redeposition and seafloor imprints caused by deep-sea polymetallic nodule mining. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, B.P.F.; Jin, Y.; Peng, Y.; Liu, D. Drilling Technology Status and Development Trends of Deep-sea Seafloor Drill. J. Mech. Eng. 2024, 60, 385–402. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Li, X.; He, Z. The Impact of Pre-treatment Processes on Semi-quantitative Analysis of Clay Minerals in Sediments. Quat. Res. 2014, 34, 635–644. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.-T.; Liu, A.; Zhou, P.; Zhao, C.; Deng, X.-J.; Zhang, C.; Huang, W. Evolution of particle crushing of coal gangue coarse-grained subgrade filler using large-scale triaxial compression. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 23, e05334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Fang, J.; Gong, W.; Tang, Q. The material composition and bindingwater characteristics of marine softsoils in Shenzhen. Acta Sci. Nat. Univ. Sunyatseni 2023, 62, 57–63. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- He, J.; Luo, F.; Yang, H.; Yu, Z. Research on physical and mechanicalproperties of soft soil in Huama LakeBasin, Ezhou City. Express Water Resour. Hydropower Inf. 2024, 45, 70–74. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wentao, L.; Yaohong, S.; Xuhui, Z.; Ningfeng, Z.; Jiangping, Y.; Haijun, H.E. Geeotechnical features of theseabed soils in the east of xishatrough and the mechanicalproperties of gas hydrate-bearing fine deposits. Mar. Geol. Quat. Geol. 2014, 34, 39–47. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Q.C.G.; Wang, W.; Shl, Z.; Llu, H. Experimental Study on the Mechanical Properties of Natural Soft Soils AlongCoast Area of Fujian Province. J. Water Resour. Archit. Eng. 2023, 21, 78–84. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hong, Z.-S.; Yin, J.; Cui, Y.-J. Compression behaviour of reconstituted soils at high initial water contents. Géotechnique 2010, 60, 691–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Qiu, C.; Xu, B.; Liu, R.; Sun, H. Experimental study on remolded yield pressure and compression characteristics of remolded soil. Port Eng. Technol. 2018, 55, 110–115. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hui, G.; Li, S.; Guo, L.; Wang, P.; Liu, B.; Wang, G.; Li, X.; Somerville, I. A review of geohazards on the northern continental margin of the South China Sea. Earth Sci. Rev. 2021, 220, 103733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Wang, J.; Meng, X.; Hua, Q.; Kan, G.; Liu, C. Seafloor Sediment Acoustic Properties on the Continental Slope in the Northwestern South China Sea. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Xia, S.; Cao, J.; Zhao, F.; Wan, K. Seismic constraints on a remnant Mesozoic forearc basin in the northeastern South China Sea. Gondwana Res. 2022, 102, 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.T.; Hsu, S.K.; Lin, A.T.S.; Su, C.C.; Babonneau, N.; Ratzov, G.; Lallemand, S.; Huang, P.-C.; Lin, L.-K.; Lin, H.-S.; et al. Changes in marine sedimentation patterns in the northeastern South China Sea in the past 35,000 years. Commun. Earth Environ. 2024, 5, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabaić, D.; Kršulja, M.; Maričić, S.; Liverić, L. The Optimization of a Subsea Pipeline Installation Configuration Using a Genetic Algorithm. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, L.; Chen, H.; Chen, S.; Liu, H. Experimental Study on Wave Current Characteristics and Stability of the Junction of Artificial Island and Subsea Tunnel. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Guo, Z.; Xu, Q. Durability of MICP-reinforced calcareous sand in marine environments: Laboratory and field experimental study. Biogeotechnics 2023, 1, 100018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Cao, J.; Zhang, G. Improved methods, properties, applications and prospects of microbial induced carbonate precipitation (MICP) treated soil: A review. Biogeotechnics 2025, 3, 100123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Z. One-dimensional consolidation creep characteristics of Tianjin muddy silty clay. China Water Transp. 2024, 14, 216–217+303. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xiang-Yu, S.; Fei, H.; Jian-Xiang, G.; Lian-Fei, K.; Guo-Qing, Z.; Xiu-Zhong, Z. A preliminary study of characteristics of secondary consolidation ofremolded clay at high pressure. Rock Soil Mech. 2018, 39, 2387–2394. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Q.; An, X.; Liu, H.; Guo, L.; Qu, J. Electric Double-Layer Effects Induce Separation of Aqueous Metal Ions. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 10922–10930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Xiong, L.; Xie, W.; Gao, K.; Shao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yu, Y.; Kou, B.; Lu, Q.; Zeng, J.; et al. Design and experimental study of core bit for hard rock drilling in deep-sea. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, F.; Li, C.; Wang, W. Development of subsea pipeline buckling, corrosion and leakage monitoring. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sampling Area | Acquisition Equipment | Depth of Water Sampled/m | Borehole Depth/m | The Number of Sediment Samples | Turbulence of Sediment Samples |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| An area in the northern South China Sea | The “Hai niu” drilling system | 2060 | 231 | 32 tubes | Minor disturbance |

| Specimen Area/cm2 | Specimen Height/cm | Initial Water Content/% | Loading Duration Per Stage/h | Loading Path/kPa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 | 2 | 27.8 | 24 | 12.5, 25, 50, 100, 200, 300, 400, 600, 800, 1600 |

| Water Depth h1/m | Sub-Seabed Depth h2/m | Water Content Ω/% | Natural Density ρ/g·cm−3 | Specific Gravity Gs | Void Ratio e | Dry Density Ρd/g·cm−3 | Degree of Saturation Sr/% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2060 | 20-50 | 103.2 | 1.41 | 2.55 | 2.69 | 0.52 | 97.64 |

| Plastic Limit ωL/% | Liquid Limit ωP/% | Plasticity Index IP | Organic Content | Soil Classification | Gravel | Silt (0.075~0.05 mm) | Clay (<0.05 mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 27.97 | 53.95 | 29.98 | 3.7% | CH | 1.45% | 72.86% | 27.14% |

| Sample Location | This Study | Northeastern South China Sea (Remolded Sediment Sample) [6] | Marine-Deposited Soft Soil (Remolded Sediment Sample) [23] | Soft Soil in Alluvial-Lacustrine Plain (Remolded Sediment Sample) [24] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water Depth h/m | 2060 | 1187 | - | 2 |

| Soil Classification | CH | MH | - | - |

| Muscovite | 29.6 | 0 | 7.35 | 0 |

| Montmorillonite | 4.6 | 24 | 10.02 | 0 |

| Illite | 4.65 | 43 | 3.18 | 35 |

| Kaolinite | 0 | 13 | 2.53 | 0 |

| Chlorite | 1.1 | 20 | 6.77 | 25 |

| Quartz | 25.19 | 0 | 67.83 | 25 |

| Orthoclase | 0 | 0 | 2.31 | 0 |

| K-Feldspar | 0 | 0 | 0 | 15 |

| Albite | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| Calcite | 28.23 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Gypsum | 1.76 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Halite | 3.87 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cristobalite | 1.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Sample Location | Water Depth h /m | Test Type | Total Cohesion c /kPa | Total Internal Friction Angle/° | Effective Cohesion c′/kPa | Effective Internal Friction Angle φ′/° |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| This study | 2060 | CU | 22.77 | 11.02 | 19.58 | 27.32 |

| Northeastern SCS (Remolded sediment sample) [6] | 1187 | CU | 3.45 | 32.2 | 1.99 | 38.2 |

| Northern SCS (Unsanctified sediment samples) [7] | 1552 | CU | 8.33 | 12.25 | 12.75 | 25.34 |

| CD | 19.84 | 23.89 | 16.92 | 25.20 | ||

| Western Sahara Trough eastern (Unsanctified sediment samples) [24] | 400–2500 | CU | 2.33–4.50 | 10.78–14.57 | 1.33–3.50 | 20.0–27.2 |

| Sample Location | Sampling Depth h/m | Compression Coefficient a1-2 /MPa−1 | Compression Modulus Es,1-2/MPa | Compression Index Cc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| This study (Remolded sediment sample) | Subaqueous 2060 | 0.302 | 4.07 | 0.107 |

| Northeastern SCS (Undisturbed sediment) [6] | Subaqueous 1187 | 1.88–1.90 | – | 0.610–0.630 |

| Eastern Xisha Trough (Undisturbed soil) [25] | Subaqueous 400–2500 | 2.28–3.57 | 1.16–1.64 | – |

| Fujian terrestrial soil (Undisturbed sediment) [26] | Subsurface 29 | 1.02 | 1.96 | 0.34 |

| Kemen clay (Remolded soil sample) [27] | – | – | – | 0.22–0.49 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Feng, Y.; Chen, Q.; Liu, G.; Huang, X.; Wang, Z.; Hu, W.; Chen, B.; Liu, S.; Xu, X. Multi-Scale Experiments and Mechanistic Insights into Hydro-Physical Properties of Saturated Deep-Sea Sediments in the South China Sea. Water 2025, 17, 3581. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243581

Feng Y, Chen Q, Liu G, Huang X, Wang Z, Hu W, Chen B, Liu S, Xu X. Multi-Scale Experiments and Mechanistic Insights into Hydro-Physical Properties of Saturated Deep-Sea Sediments in the South China Sea. Water. 2025; 17(24):3581. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243581

Chicago/Turabian StyleFeng, Yan, Qiunan Chen, Guangping Liu, Xiaocheng Huang, Zengliang Wang, Wei Hu, Bingchu Chen, Shunkai Liu, and Xiaodi Xu. 2025. "Multi-Scale Experiments and Mechanistic Insights into Hydro-Physical Properties of Saturated Deep-Sea Sediments in the South China Sea" Water 17, no. 24: 3581. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243581

APA StyleFeng, Y., Chen, Q., Liu, G., Huang, X., Wang, Z., Hu, W., Chen, B., Liu, S., & Xu, X. (2025). Multi-Scale Experiments and Mechanistic Insights into Hydro-Physical Properties of Saturated Deep-Sea Sediments in the South China Sea. Water, 17(24), 3581. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243581