Experimental Evaluation of the Performance of a Flat Sheet Reverse Osmosis Membrane Under Variable and Intermittent Operation Emulating a Photovoltaic-Driven Desalination System

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Experimentally evaluate the performance of a flat sheet SWRO membrane emulating real-world, battery-less RE conditions that involve both intermittent operation (8-h daily cycles) and variable input dynamics (sunny and cloudy day profiles).

- Investigate the influence of abrupt and unregulated fluctuations in feed pressure and flowrate on key membrane performance indicators such as net driving pressure, water permeability, membrane resistance and salt rejection.

- Assess the effectiveness of daily rinsing as a mitigation strategy by comparing membrane performance over three consecutive days with and without rinsing, providing insights into membrane compaction, and surface deposition, under operational conditions that emulate real PVRO desalination systems.

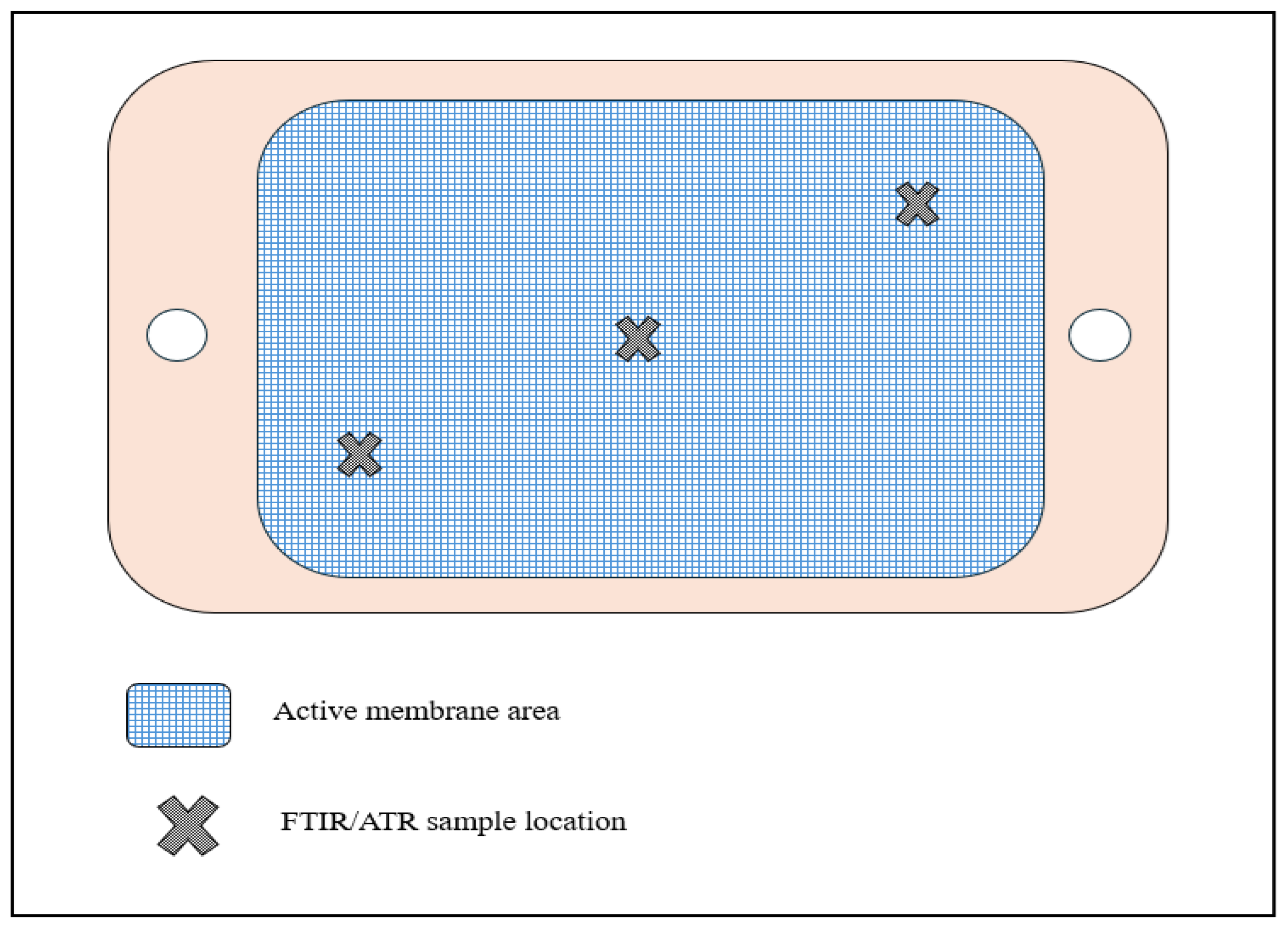

- Perform Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy with Attenuated Total Reflectance (FTIR/ATR) analysis to investigate potential compaction or surface deposition of the membrane material after exposure to the different operational scenarios.

2. Experimental Setup

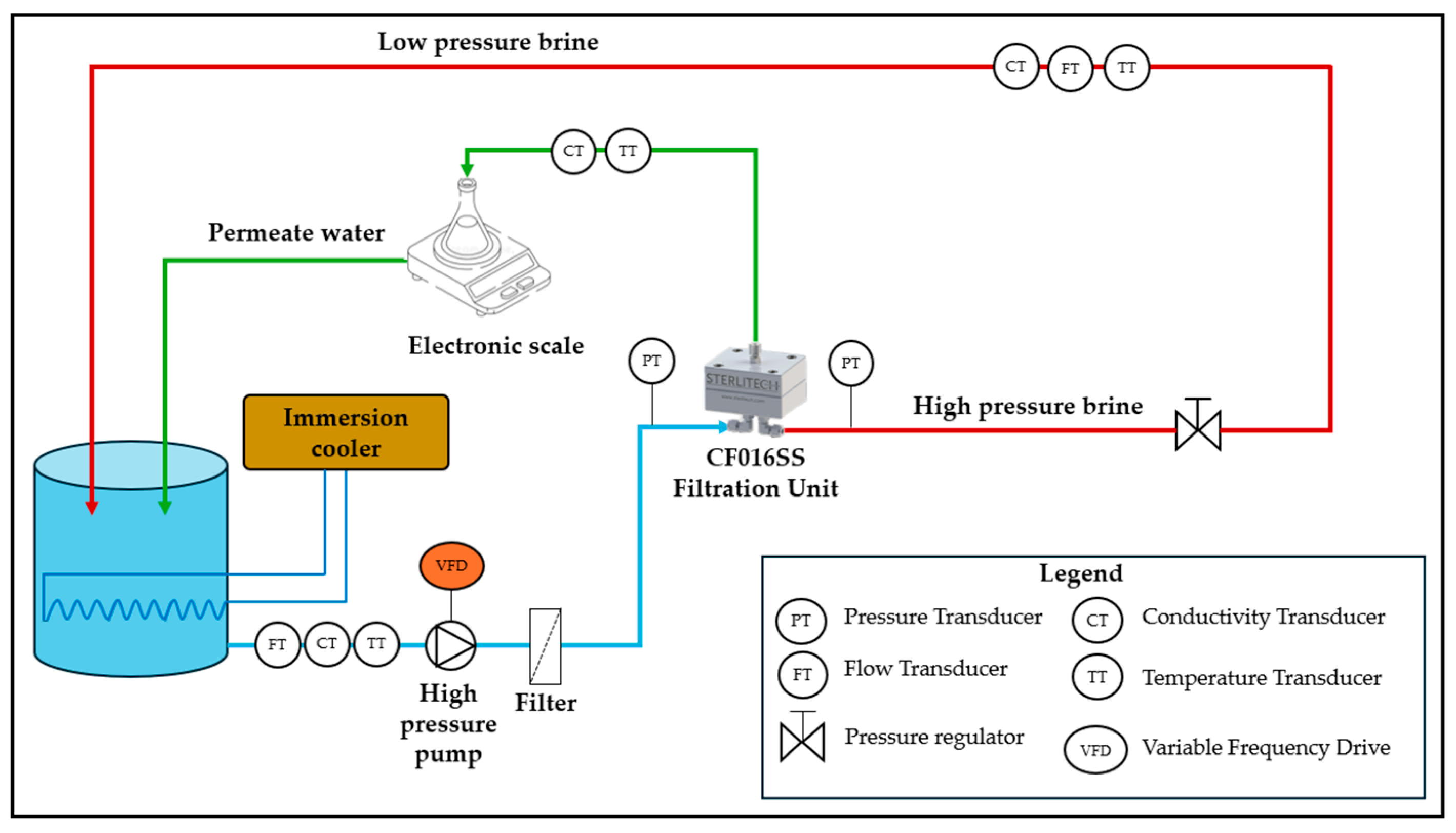

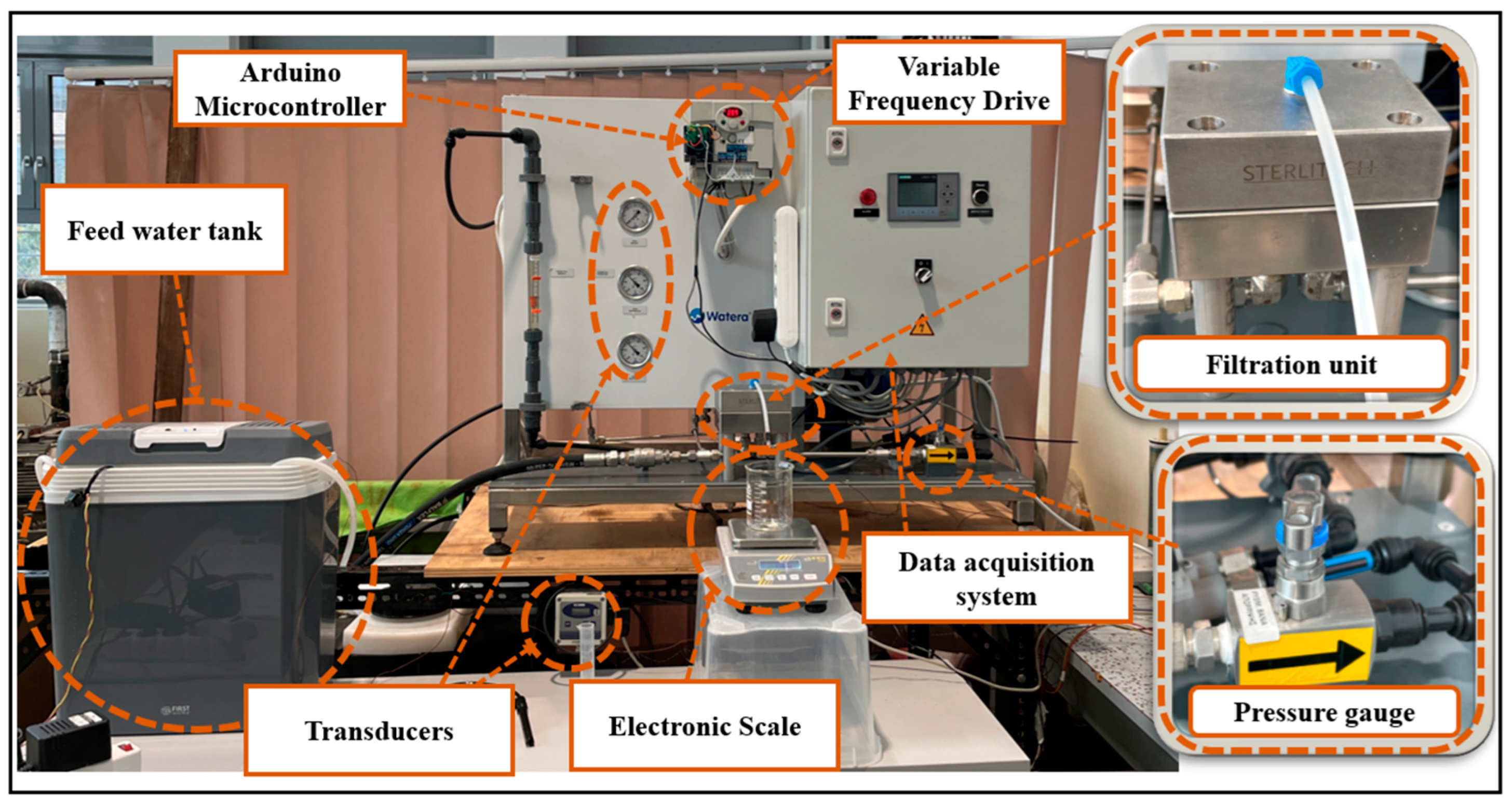

2.1. Lab Scale Filtration System

2.1.1. Feed Water Tank

2.1.2. Pretreatment System

2.1.3. High Pressure Motor Pump Assembly

2.1.4. Membrane Cell

2.1.5. Flat Sheet Membrane

2.1.6. Pressure Regulator

2.2. Filtration System Instrumentation

- Two analog pressure transmitters, A-10 (WIKA, Alexander Wiegand SE & Co., Klingenberg, Germany), to measure the feed (membrane inlet) and brine (membrane outlet) water pressures across the membrane cell.

- Three inline conductivity sensors, GLMU 200, MP (Greisinger GmbH, Münzbach, Austria), to measure the electrical conductivity of the feed and brine streams (range: 0–200 mS/cm) and the permeate stream (range: 0–2000 µS/cm).

- A precision electronic scale, PCB 1000-2 (KERN & SOHN GmbH, Balingen-Frommern, Germany), for accurate permeate flux measurement.

- A digital flowmeter, FHKK–PVDF (Greisinger GmbH, Münzbach, Austria), to measure brine flow rates within the range of 0.03–5 L/min.

- Three type-T thermocouples to monitor the temperature of the feed, brine, and permeate streams.

- An energy analyzer Fetmo D4, (Electrex s.r.l., Reggio Emilia, Italy), to record the electrical power consumption of the filtration unit.

- An immersion cooler and temperature controller installed in the feed-water tank to maintain a stable feed-water temperature of 25 °C

2.3. FTIR/ATR Spectrometer for Membrane Surface Characterization

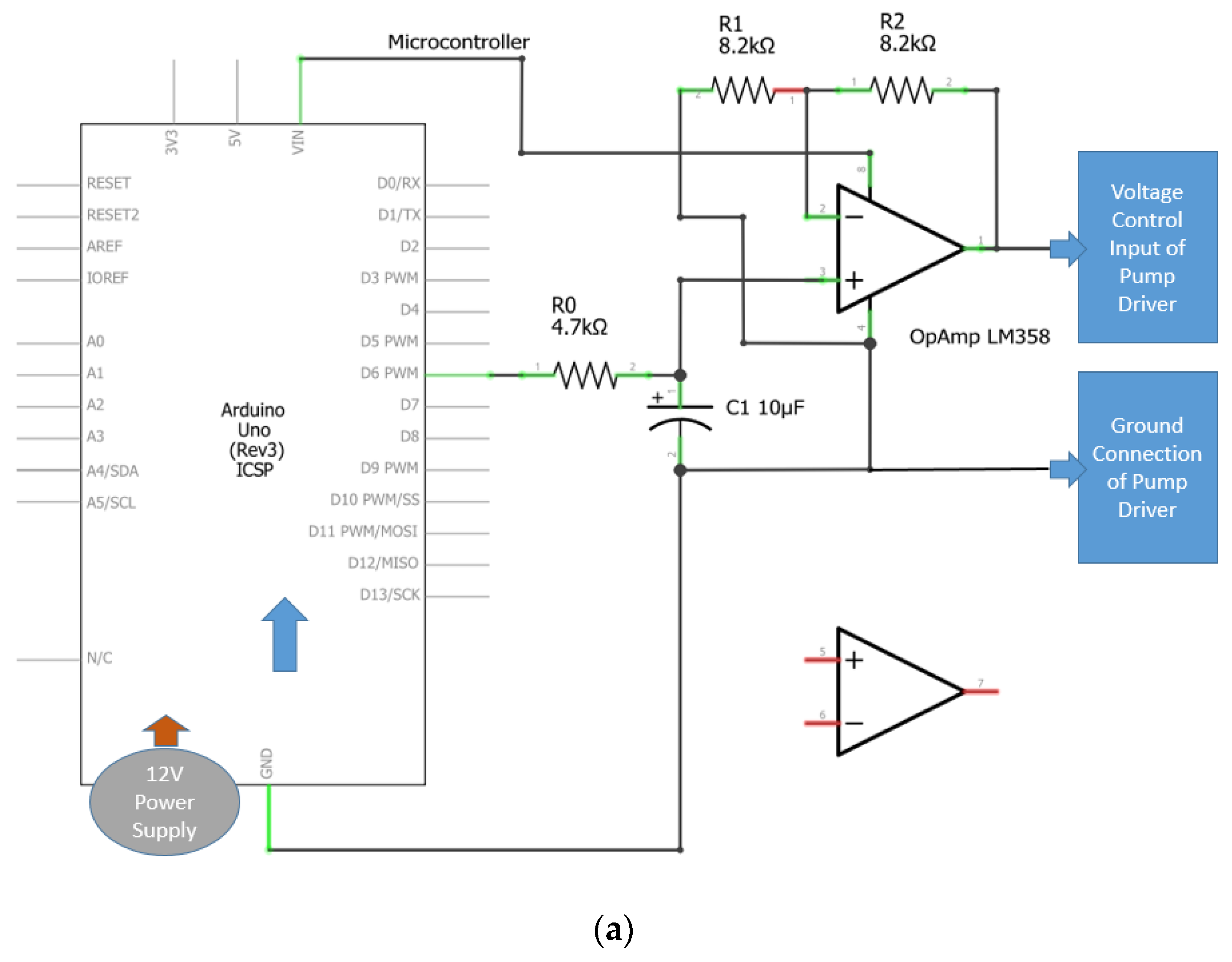

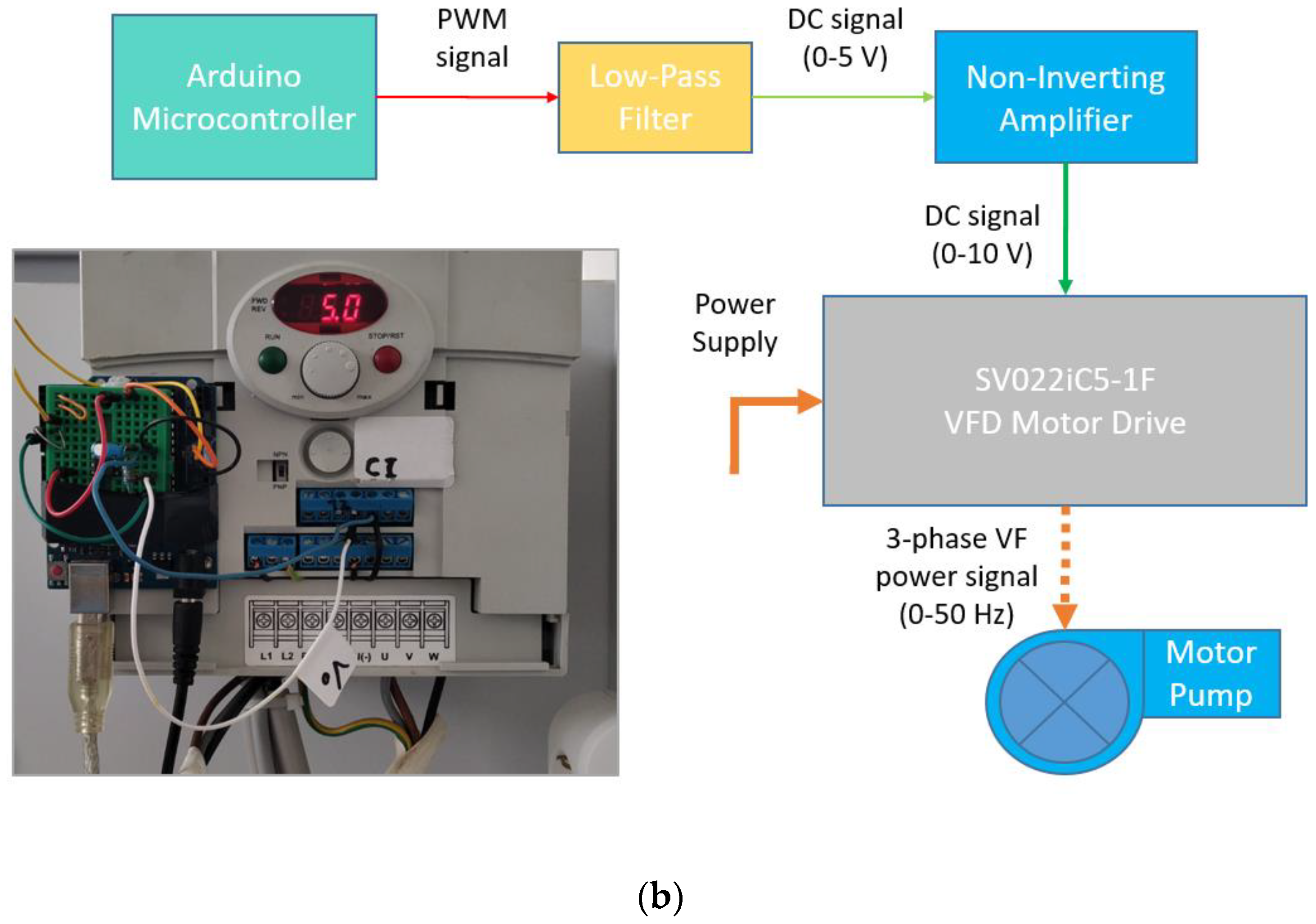

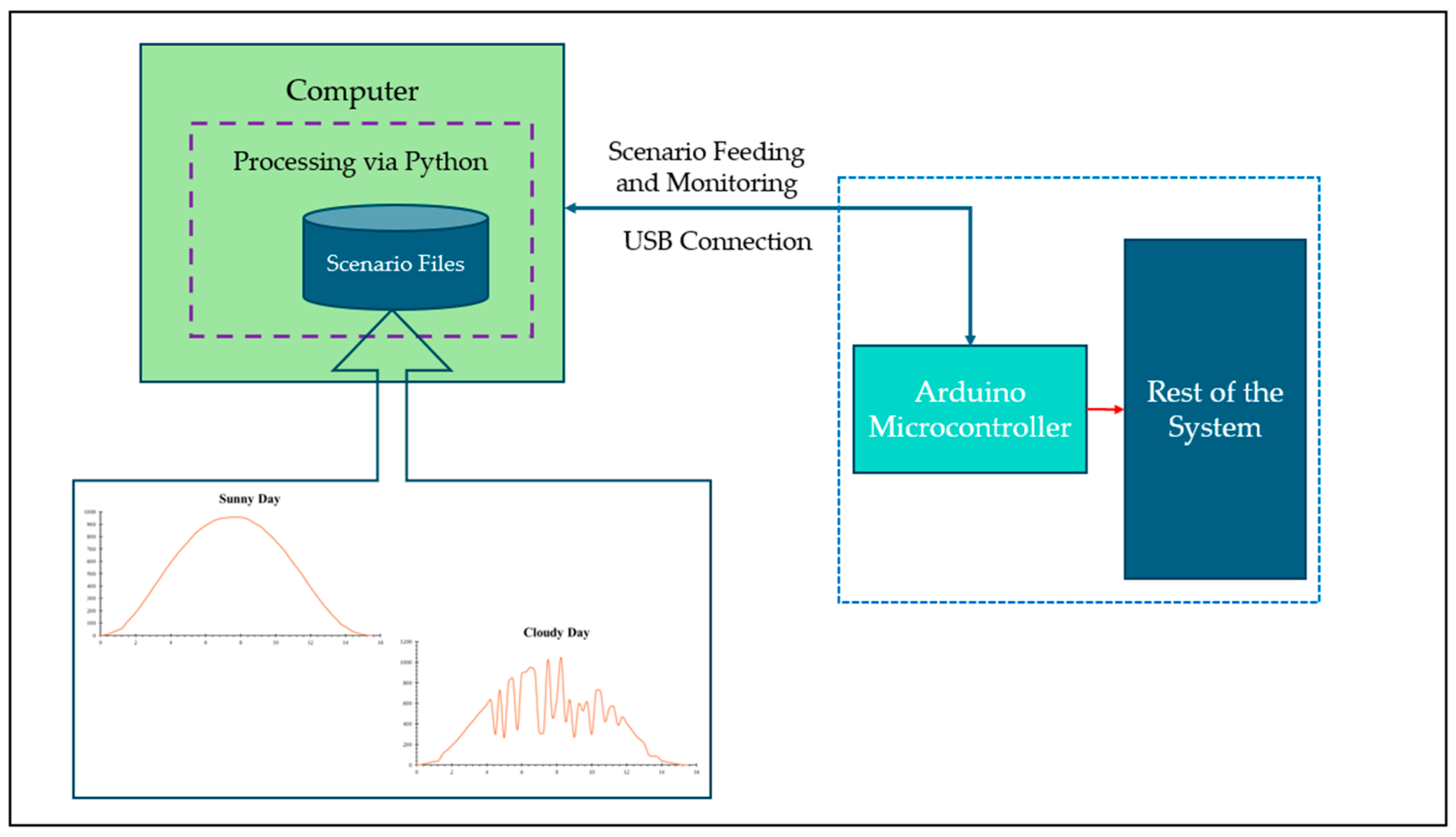

2.4. Enhancing the Control of the System

3. Methodology and Calculations

3.1. Methodology of Experimental Investigation

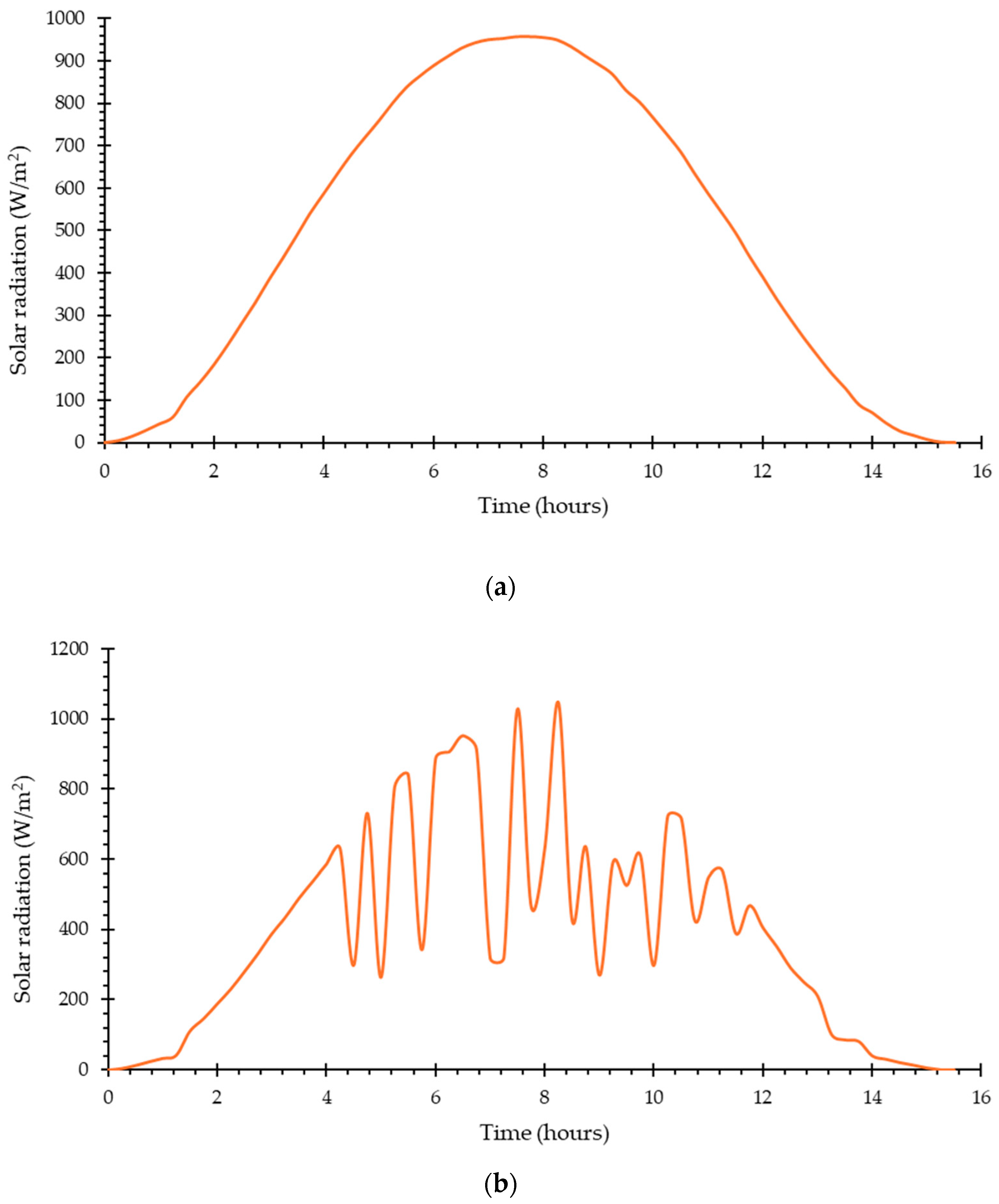

- (a)

- Scenario #1: Full load operation emulating power production from a PV system with batteries.

- (b)

- Scenario #2: Variable operation emulating power production from a PV system on sunny days.

- (c)

- Scenario #3: Variable operation emulating power production from a PV system on cloudy days.

3.2. Membrane Preparation and Performance Evaluation

3.3. Membrane Autopsy via FTIR/ATR Analysis

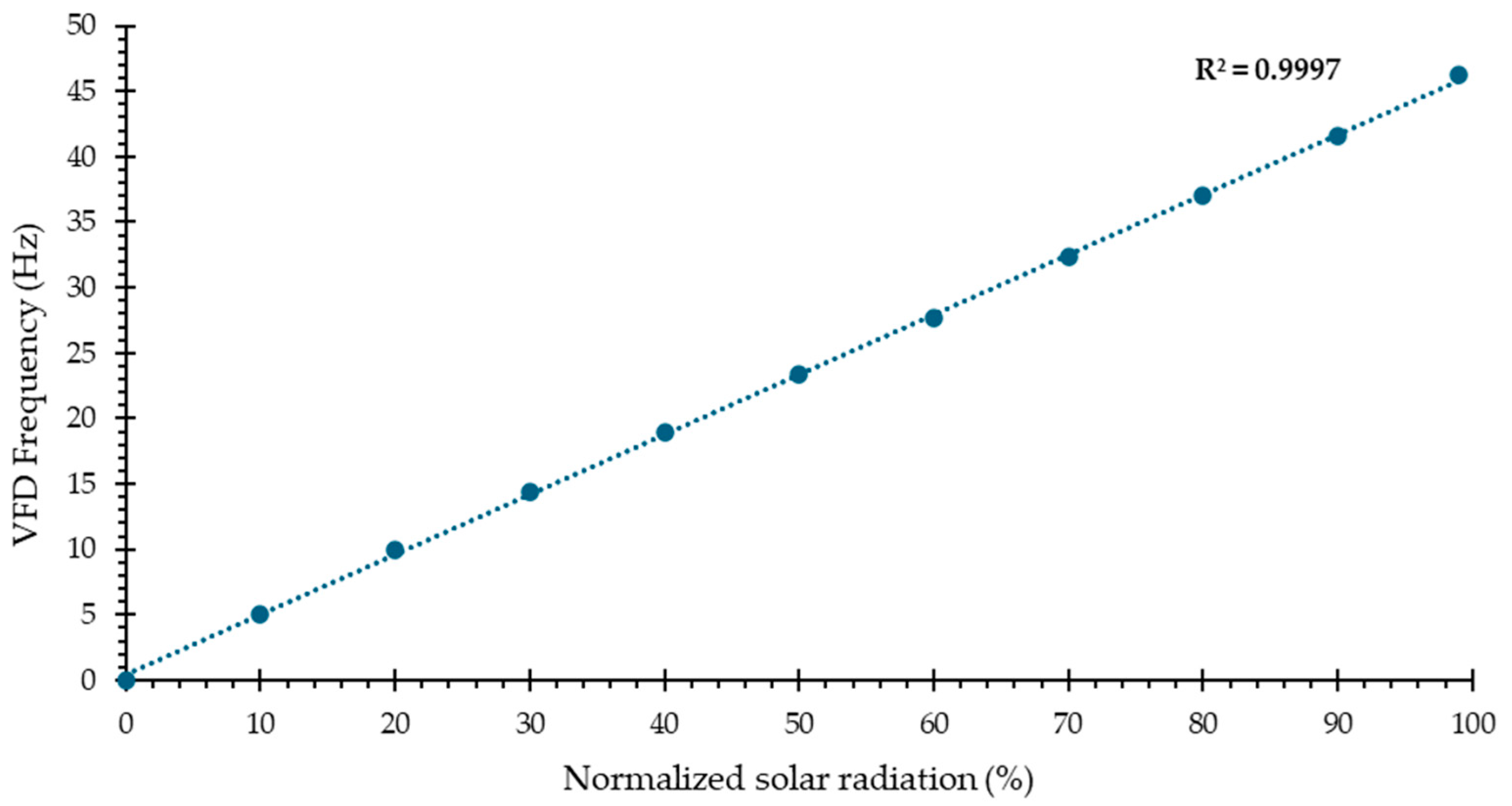

3.4. Generating Operational Scenarios Emulating the PV Power Supply Conditions

3.5. Calculations

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. General Overview and Inlet Parameters

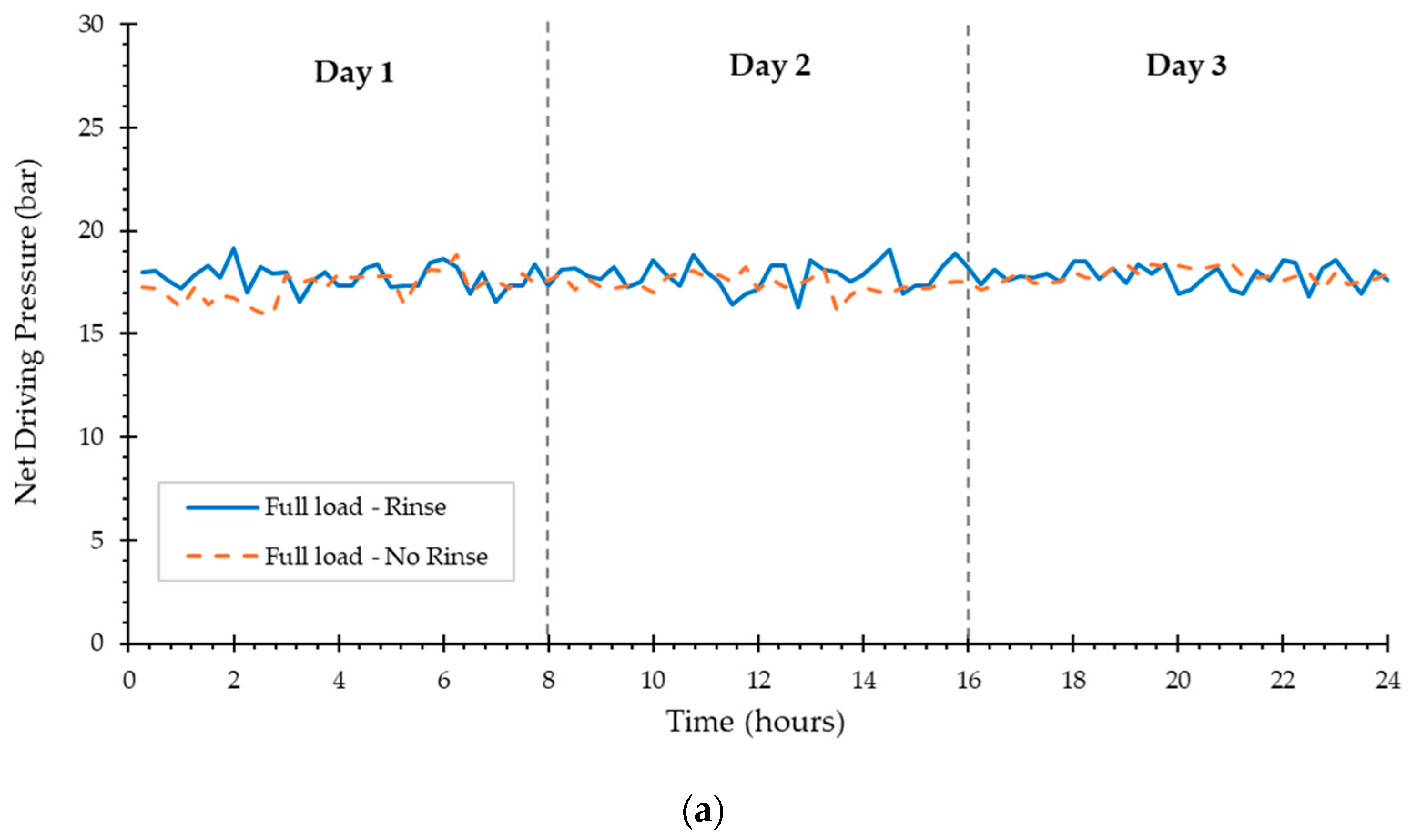

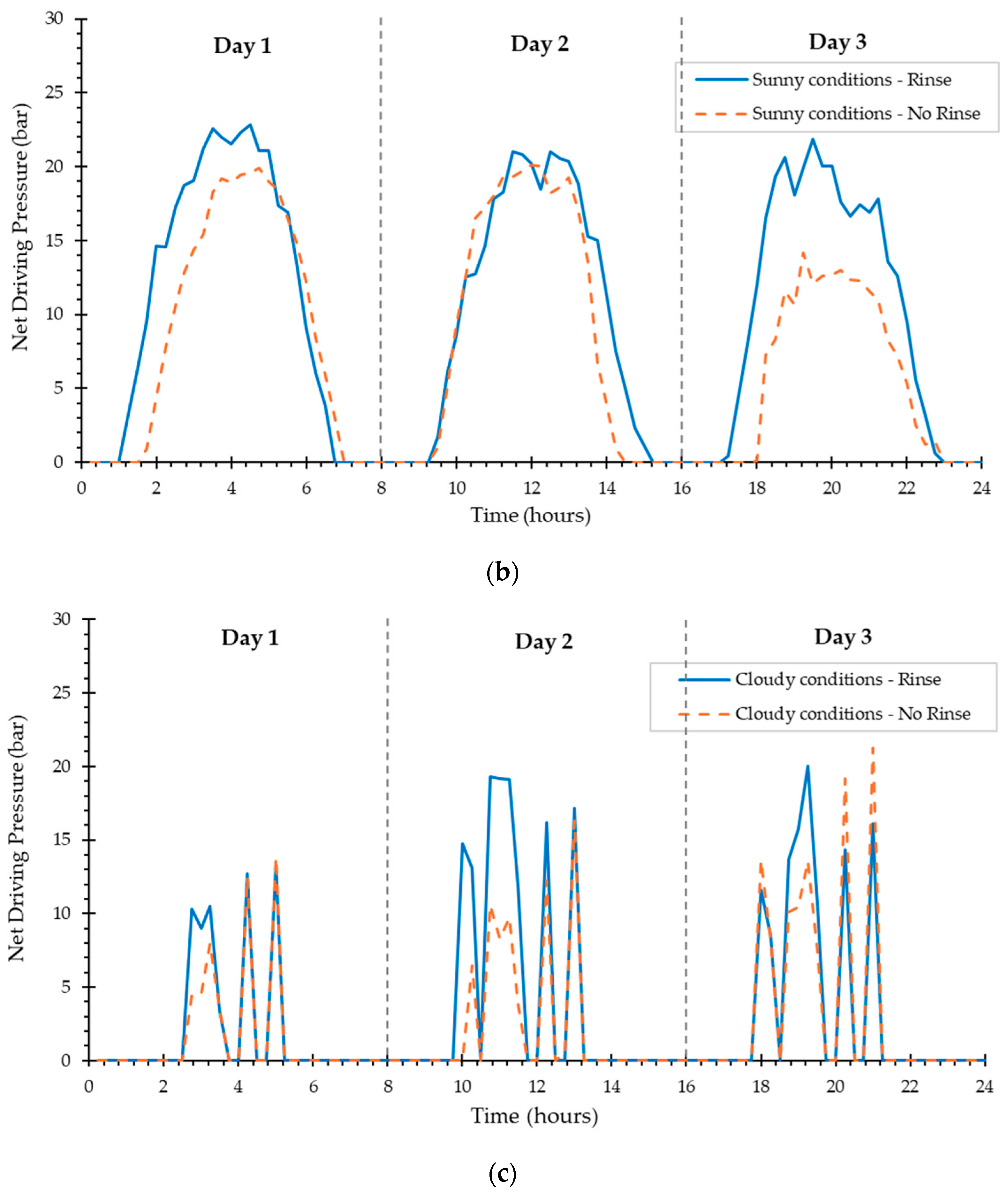

4.2. Effect of Operational Conditions on Net Driving Pressure

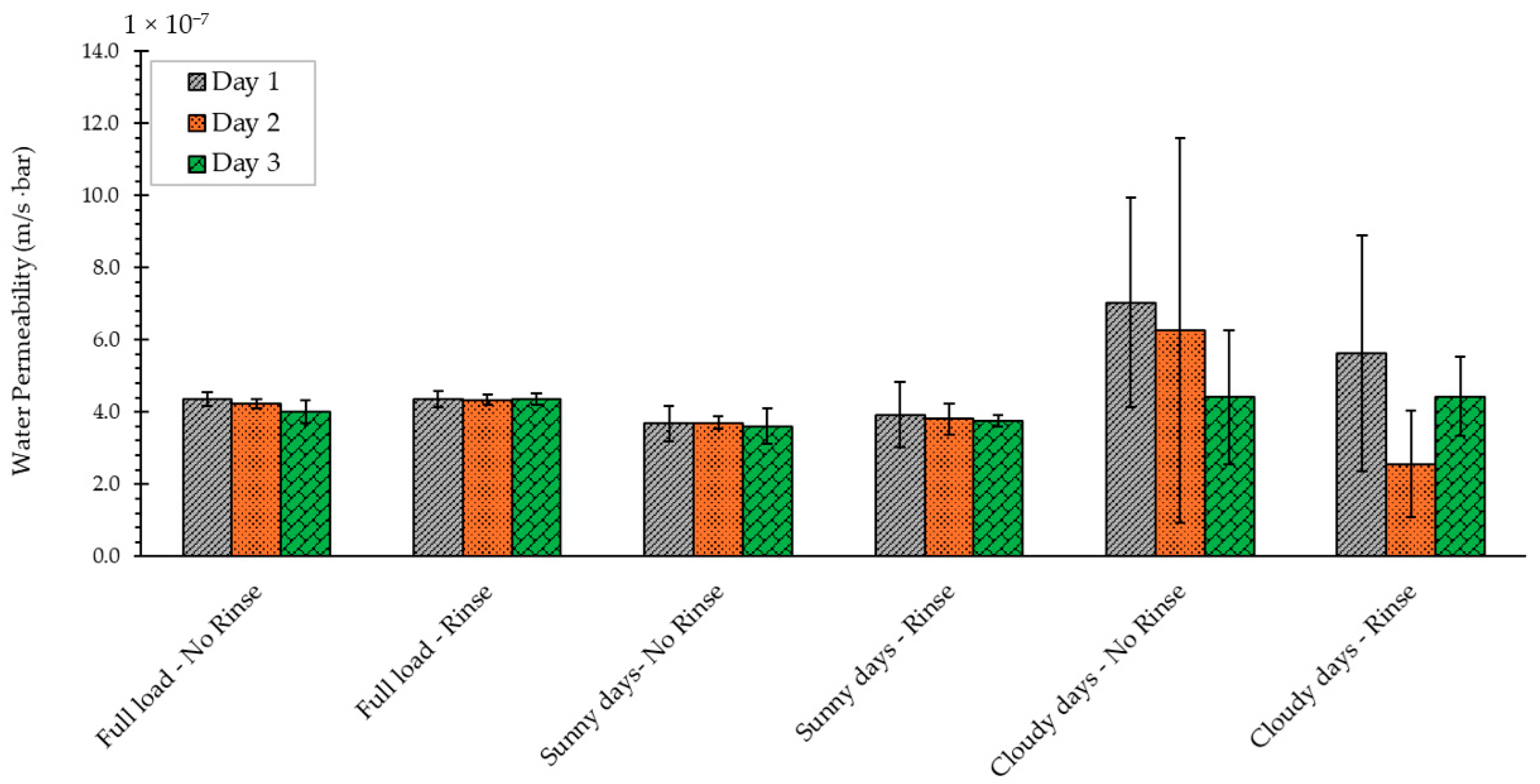

4.3. Comparison of the Effect of Operating Conditions on Water Permeability

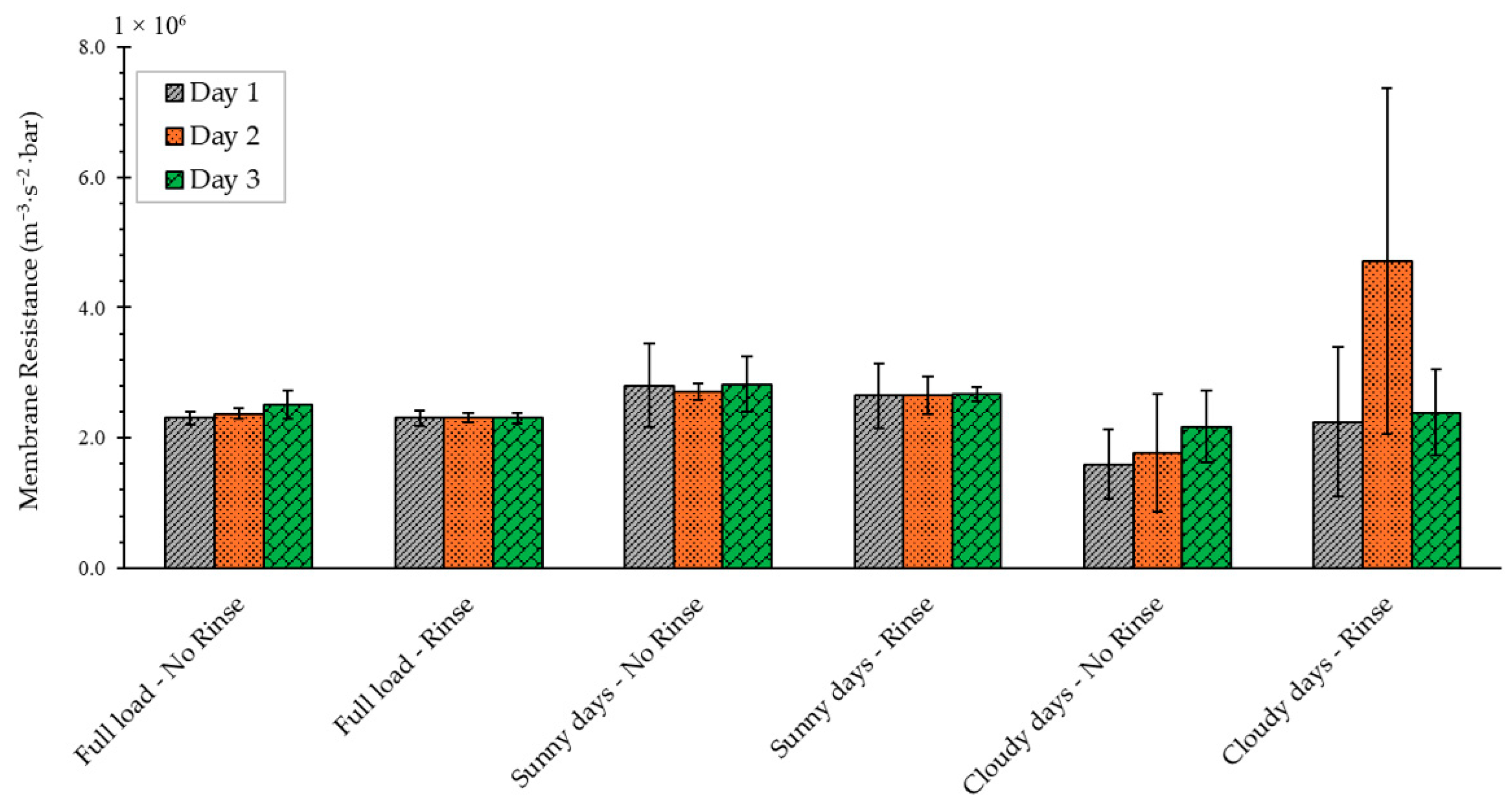

4.4. Comparison of the Effect of Operational Conditions on Membrane Resistance

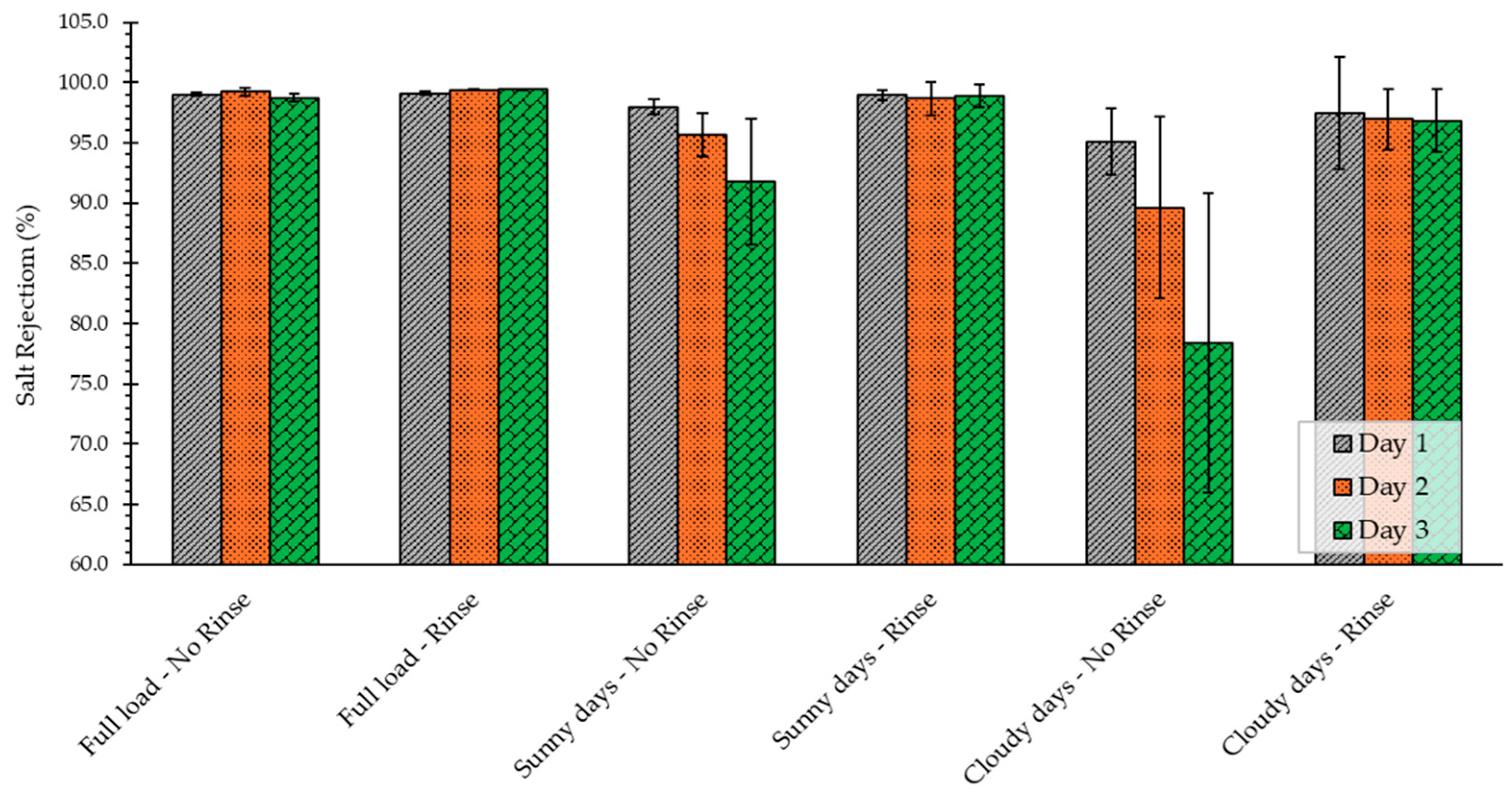

4.5. Comparison of the Effect of Operational Conditions on Salt Rejection

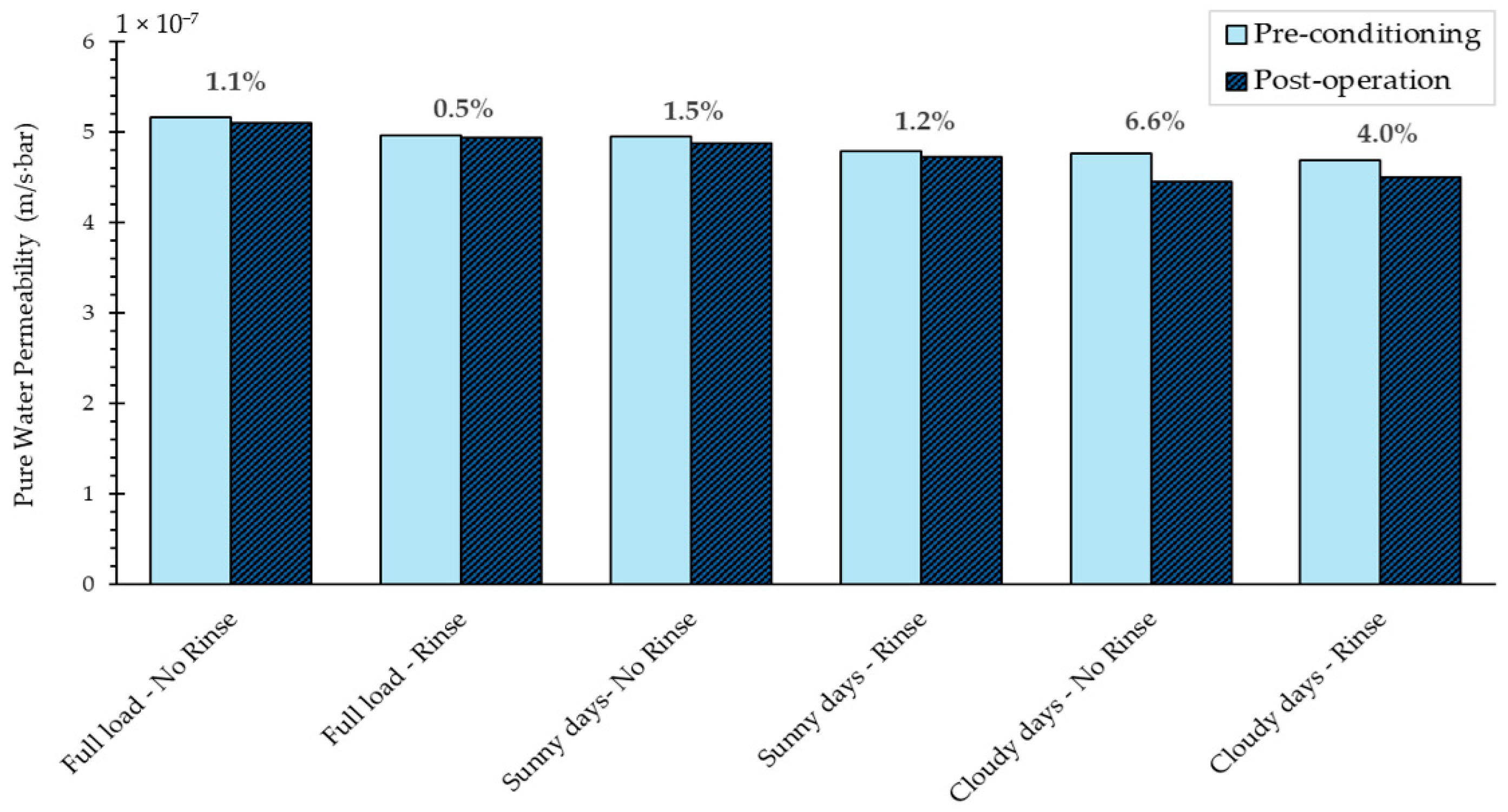

4.6. Comparison of the Effect of Operational Conditions on Pure Water Permeability

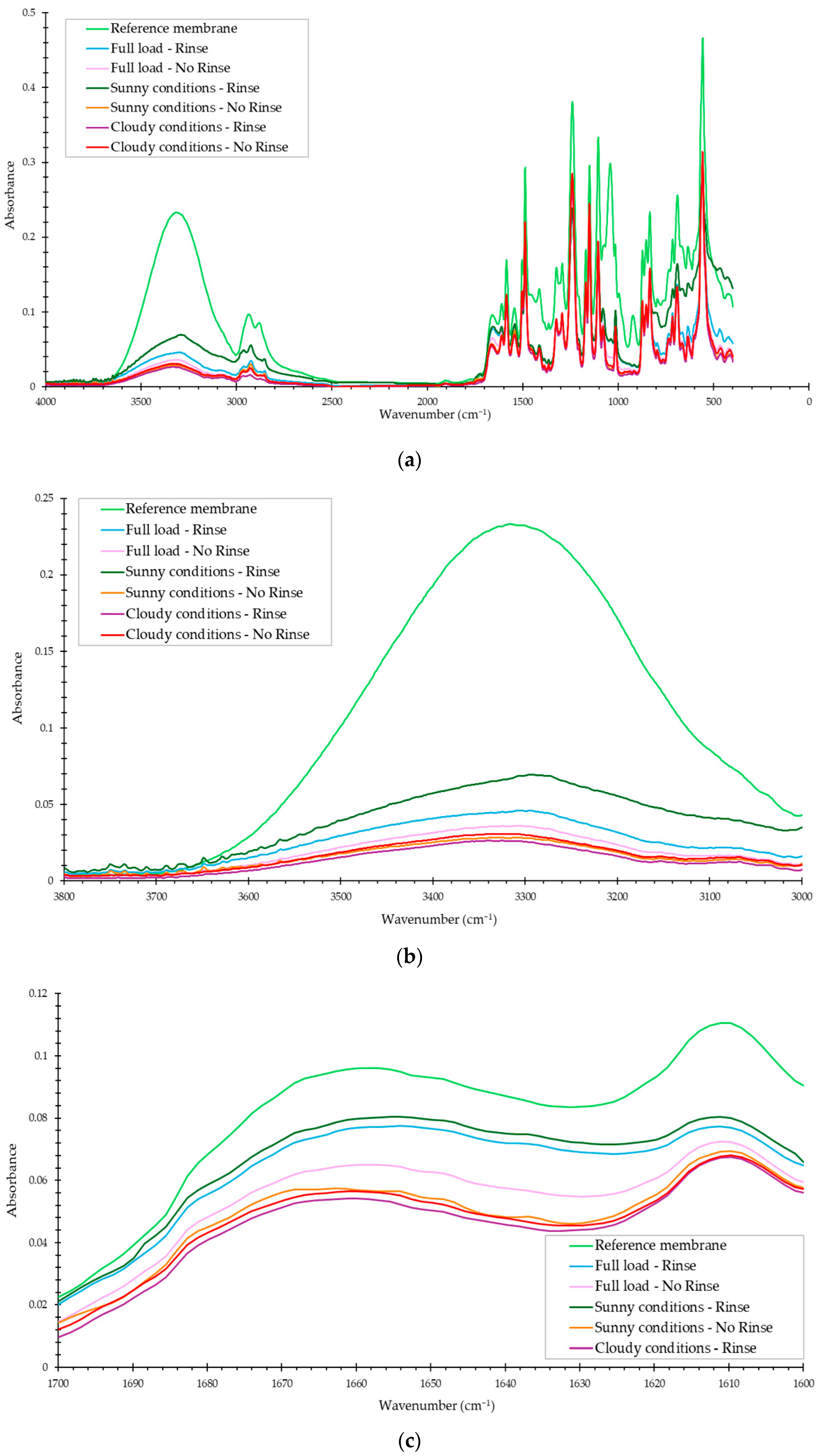

4.7. Comparison of FTIR/ATR Spectroscopic Analysis of RO Membranes

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ATR | Attenuated Total Reflectance |

| BWRO | Brackish Water Reverse Osmosis |

| FTIR | Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| HR | Hydraulic Resistance |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| PWM | Pulse Width Modification |

| RE | Renewable Energy |

| RO | Reverse Osmosis |

| SWRO | Seawater Reverse Osmosis |

| VFD | Variable Frequency Drive |

References

- United Nations Summary Progress Update 2021: SDG 6—Water and Sanitation for Al. Available online: https://www.unwater.org/publications/summary-progress-update-2021-sdg-6-water-and-sanitation-all (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- UNESCO World Water Assessment Programme. The United Nations World Water Development Report 2023: Partnerships and Cooperation for Water; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Mekonnen, M.M.; Hoekstra, A.Y. Four Billion People Facing Severe Water Scarcity. Sci. Adv. 2016, 2, e1500323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Climate Change 2023 Synthesis Report, A Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [CrossRef]

- ESCWA Water Development Report 10-The Water Action Decade (2018–2028): Midterm Review in the Arab Region–Algeria. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/algeria/escwa-water-development-report-10-water-action-decade-2018-2028-midterm-review-arab-region (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Desalination-European Commission. Available online: https://blue-economy-observatory.ec.europa.eu/eu-blue-economy-sectors/desalination_en (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- De Roo, A.; Trichakis, I.; Bisselink, B.; Gelati, E.; Pistocchi, A.; Gawlik, B. The Water-Energy-Food-Ecosystem Nexus in the Mediterranean: Current Issues and Future Challenges. Front. Clim. 2021, 3, 782553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyl-Mazzega, M.-A. The Geopolitics of Seawater Desalination in Association with; Ifri: Paris, France, 2022; ISBN 9791037306616. [Google Scholar]

- Elsaid, K.; Sayed, E.T.; Abdelkareem, M.A.; Mahmoud, M.S.; Ramadan, M.; Olabi, A.G. Environmental Impact of Emerging Desalination Technologies: A Preliminary Evaluation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 104099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, F.E.; Khalil, A.; Hilal, N. Emerging Desalination Technologies: Current Status, Challenges and Future Trends. Desalination 2021, 517, 115183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Which Methods Are Used Most for Desalination?|Fluence. Available online: https://www.fluencecorp.com/common-methods-used-for-desalination/ (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Zhang, M.; Yu, S.; Shi, C.; Wang, H.; Chang, N. Carbon Footprint Analysis and Carbon Neutrality Potential of Desalination by Reverse Osmosis for Different Applications Basd on Life Cycle Assessment Method. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 40842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do Thi, H.T.; Tóth, A.J. Investigation of Carbon Footprints of Three Desalination Technologies: Reverse Osmosis (RO), Multi-Stage Flash Distillation (MSF) and Multi-Effect Distillation (MED). Period. Polytech. Chem. Eng. 2023, 67, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagopoulos, A. Assessing the Energy Footprint of Desalination Technologies and Minimal/Zero Liquid Discharge (MLD/ZLD) Systems for Sustainable Water Protection via Renewable Energy Integration. Energies 2025, 18, 962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EWEC Forecasts Halving CO2 Emissions from Water and Electricity Production by 2025|Emirates Water and Electricity Company (EWEC). Available online: https://www.mediaoffice.abudhabi/en/energy/ewec-forecasts-halving-co2-emissions-from-water-and-electricity-production-by-2025/ (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Kyriakarakos, G.; Papadakis, G. Is Small Scale Desalination Coupled with Renewable Energy a Cost-Effective Solution? Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 5419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mito, M.T.; Ma, X.; Albuflasa, H.; Davies, P.A. Reverse Osmosis (RO) Membrane Desalination Driven by Wind and Solar Photovoltaic (PV) Energy: State of the Art and Challenges for Large-Scale Implementation. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 112, 669–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Cáceres González, R.A.; Hatzell, M.C.; Hatzell, K.B. Challenges and Roadmap for Solar-Thermal Desalination. ACS EST Eng. 2023, 3, 1055–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hamzawi, H.A.H.; Sailawi, A.S.A. Al Optimized Multi-Generation System for Sustainable Desalination and Power Production Using Solar-Driven Multi-Effect Distillation (MED) in Basra, Iraq. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2025, 85, 101684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Agouz, S.A.; Zayed, M.E.; Abo Ghazala, A.M.; Elbar, A.R.A.; Shahin, M.; Zakaria, M.Y.; Ismaeil, K.K. Solar Thermal Feed Preheating Techniques Integrated with Membrane Distillation for Seawater Desalination Applications: Recent Advances, Retrofitting Performance Improvement Strategies, and Future Perspectives. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2022, 164, 595–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abolli, S.; Ghordouei Milan, E.; Bashardoust, P.; Alimohammadi, M. What Is the Carbon Footprint of Reverse Osmosis in Water Treatment Plants? A Systematic Review Protocol. Environ. Evid. 2023, 12, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, I.; Chen, Y.; Huang, S.; Rahman, M.M. Recycled Value-Added Circular Energy Materials for New Battery Application: Recycling Strategies, Challenges, and Sustainability-a Comprehensive Review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 108728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, C.; La Mantia, F. Insights into Desalination Battery Concepts: Current Challenges and Future Perspectives. Chem. Commun. 2023, 59, 6437–6452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Lv, Y.; Ji, M.; Zhao, F. Evaluation and Economic Analysis of Battery Energy Storage in Smart Grids with Wind–Photovoltaic. Int. J. Low-Carbon Technol. 2024, 19, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura, L.; Nuez, I.; Gómez, A. Direct Integration of a Renewable Energy into a Reverse Osmosis Process. In Proceedings of the European Wind Energy Conference and Exhibition 2006, EWEC 2006, Athens, Greece, 27 February–2 March 2006; Volume 3, pp. 2240–2246. [Google Scholar]

- Mito, M.T.; Ma, X.; Albuflasa, H.; Davies, P.A. Variable Operation of a Renewable Energy-Driven Reverse Osmosis System Using Model Predictive Control and Variable Recovery: Towards Large-Scale Implementation. Desalination 2022, 532, 115715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laissaoui, M.; Palenzuela, P.; Sharaf Eldean, M.A.; Nehari, D.; Alarcón-Padilla, D.-C. Techno-Economic Analysis of a Stand-Alone Solar Desalination Plant at Variable Load Conditions. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2018, 133, 659–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntavou, E.; Kosmadakis, G.; Manolakos, D.; Papadakis, G.; Papantonis, D. Experimental Evaluation of a Multi-Skid Reverse Osmosis Unit Operating at Fluctuating Power Input. Desalination 2016, 398, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriou, E.; Mohamed, E.S.; Kyriakarakos, G.; Papadakis, G. Experimental Investigation of the Performance of a Reverse Osmosis Desalination Unit under Full- and Part-Load Operation. Desalination Water Treat. 2015, 53, 3170–3178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriou, E.; Mohamed, E.S.; Karavas, C.; Papadakis, G. Experimental Comparison of the Performance of Two Reverse Osmosis Desalination Units Equipped with Different Energy Recovery Devices. Desalination Water Treat. 2015, 55, 3019–3026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mito, M.T.; Ma, X.; Albuflasa, H.; Davies, P.A. Modular Operation of Renewable Energy-Driven Reverse Osmosis Using Neural Networks for Wind Speed Prediction and Scheduling. Desalination 2023, 567, 116950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriou, E.; Loukatos, D.; Tampakakis, E.; Arvanitis, K.G.; Papadakis, G. An Experimental Investigation of an Open-Source and Low-Cost Control System for Renewable-Energy-Powered Reverse Osmosis Desalination. Electronics 2024, 13, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire-Gormaly, M.; Bilton, A. An Experimental System for Characterization of Membrane Fouling of Solar Photovoltaic Reverse Osmosis Systems Under Intermittent Operation. Desalination Water Treat. 2017, 73, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire-Gormaly, M. Experimental Characterization of Membrane Fouling Under Intermittent Operation and Its Application to the Optimization of Solar Photovoltaic Powered Reverse Osmosis Drinking Water Treatment Systems; University of Toronto: Toronto, ON, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, B.S.; Capão, D.P.S.; Früh, W.G.; Schäfer, A.I. Renewable Energy Powered Membrane Technology: Impact of Solar Irradiance Fluctuations on Performance of a Brackish Water Reverse Osmosis System. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2015, 156, 379–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-García, A.; Nuez, I. Long-Term Intermittent Operation of a Full-Scale BWRO Desalination Plant. Desalination 2020, 489, 114526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriou, E.; Boutikos, P.; Mohamed, E.S.; Koziel, S.; Papadakis, G. Theoretical Performance Prediction of a Reverse Osmosis Desalination Membrane Element under Variable Operating Conditions. Desalination 2017, 419, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriou, E.; Camacho-Espino, J.; Anastasiou, A.; Papadakis, G. Experimental Investigation of the Performance of a Seawater Reverse Osmosis Desalination System Operating under Variable Feed Flowrate Pressure and Temperature Conditions. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 115778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire-Gormaly, M.; Bilton, A.M. Experimental Quantification of the Effect of Intermittent Operation on Membrane Performance of Solar Powered Reverse Osmosis Desalination Systems. Desalination 2018, 435, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, M.; Al-Obaidi, M.A.; Hadadian, Z.; Moradi, M.; Haghighi, A.; Mujtaba, I.M. Performance Evaluation of a Brackish Water Reverse Osmosis Pilot-Plant Desalination Process Under Different Operating Conditions: Experimental Study. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2021, 4, 100134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aladwani, S.H.; Al-Obaidi, M.A.; Mujtaba, I.M. Performance of Reverse Osmosis Based Desalination Process Using Spiral Wound Membrane: Sensitivity Study of Operating Parameters under Variable Seawater Conditions. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2021, 5, 100284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitterley, K.A.; Cath, T.J.; Jenne, D.S.; Yu, Y.H.; Cath, T.Y. Performance of Reverse Osmosis Membrane with Large Feed Pressure Fluctuations from a Wave-Driven Desalination System. Desalination 2022, 527, 115546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.; Ma, K.; Childress, A.E. Compaction of Pressure-Driven Water Treatment Membranes: Real-Time Quantification and Analysis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 18404–18413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, T.K.; Folley, M.; Lamont-Kane, P.; Frost, C. Performance of a SWRO Membrane under Variable Flow Conditions Arising from Wave Powered Desalination. Desalination 2024, 571, 117069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carta, J.A.; Cabrera, P.; Melián-Martel, N.; Arenas-Urrea, S. Experimental Investigation of the Effect of Intermittent Operation on Membranes in Wind-Powered SWRO Plants, Focusing on Frequent Start-Stop Scenarios. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2025, 25, 100848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupont. FilmTecTM Reverse Osmosis Membranes Technical Manual. Dupont Filmtec 2023. Available online: https://www.dupont.com/content/dam/water/amer/us/en/water/public/documents/en/RO-NF-FilmTec-Manual-45-D01504-en.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Sterlitech Corporation. Crossflow Filtration Handbook; Starlitech Co.: Kent, WA, USA, 2018; Available online: https://www.sterlitech.com/media/wysiwyg/Manual2018/Manual_CF016SS_CF.pdf?srsltid=AfmBOoqnfcFFYij5U8lKDfBzSDHDUEIcatSymoeZEN0LOurpuX996oWL (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Jankhah, S. Hydrodynamic Conditions in Bench-Scale Membrane Flow-Cells Used to Mimic Conditions Present in Full-Scale Spiral-Wound Elements. Membr. Technol. 2017, 2017, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, D.M.; Ritt, C.L.; Verbeke, R.; Dickmann, M.; Egger, W.; Vankelecom, I.F.J.; Elimelech, M. Thin Film Composite Membrane Compaction in High-Pressure Reverse Osmosis. J. Memb. Sci. 2020, 610, 118268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SterliTECH Tip: Membrane Pre-Conditioning. Available online: https://www.sterlitech.com/blog/post/tech-tips-may-2016-membrane-pre-conditioning (accessed on 26 April 2025).

- Loukatos, D.; Sarakis, L.; Kontovasilis, K.; Skianis, C.; Kormentzas, G. Tools and Practices for Measurement-Based Network Performance Evaluation. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE 18th International Symposium on Personal, Indoor and Mobile Radio Communications, Athens, Greece, 3–7 September 2007; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Penña, N.; Gallego, S.; del Vigo, F.; Chesters, S.P. Evaluating Impact of Fouling on Reverse Osmosis Membranes Performance. Desalination Water Treat. 2013, 51, 958–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamah, S.C.; Goh, P.S.; Ismail, A.F.; Suzaimi, N.D.; Ahmad, N.A.; Lee, W.J. Flux Enhancement in Reverse Osmosis Membranes Induced by Synergistic Effect of Incorporated Palygorskite/Chitin Hybrid Nanomaterial. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 105432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddah, H.A. Simulating Fouling Impact on the Permeate Flux in High-Pressure Membranes. Int. J. Adv. Appl. Sci. 2021, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuwatfa, W.H.; AlSawaftah, N.; Darwish, N.; Pitt, W.G.; Husseini, G.A. A Review on Membrane Fouling Prediction Using Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs). Membranes 2023, 13, 685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire-Gormaly, M.; Bilton, A.M. Impact of Intermittent Operation on Reverse Osmosis Membrane Fouling for Brackish Groundwater Desalination Systems. J. Membr. Sci. 2019, 583, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.A.; Amin, S.; Mohamed, A.A. Fouling in Reverse Osmosis Membranes: Monitoring, Characterization, Mitigation Strategies and Future Directions. Heliyon 2023, 9, e14908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-García, A.; Al-Obaidi, M.A.; Nuez, I.; Mujtaba, I.M. Impact of SWMM Fouling and Position on the Performance of SWRO Systems in Operating Conditions of Minimum SEC. Membranes 2023, 13, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, N.R.; Cherukupally, P.; Sodhi, R.; Bilton, A. End-of-the-Day Rinsing for Improved Maintainability of Intermittently Operated Small-Scale Photovoltaic-Powered Reverse Osmosis Systems. Desalination 2025, 599, 118439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; He, J.; Quezada-Renteria, J.A.; Le, J.; Au, K.; Guo, K.; Xiao, M.; Wang, X.; Dlamini, D.; Fan, H.; et al. Polyamide Reverse Osmosis Membrane Compaction and Relaxation: Mechanisms and Implications for Desalination Performance. J. Memb. Sci. 2024, 706, 122893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werber, J.R.; Osuji, C.O.; Elimelech, M. Materials for Next-Generation Desalination and Water Purification Membranes. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2016, 1, 16018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoek, E.M.V.; Allred, J.; Knoell, T.; Jeong, B.H. Modeling the Effects of Fouling on Full-Scale Reverse Osmosis Processes. J. Memb. Sci. 2008, 314, 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Li, Y.; Ladewig, B.P. A Review of Reverse Osmosis Membrane Fouling and Control Strategies. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 595, 567–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karavas, C.S.; Arvanitis, K.G.; Kyriakarakos, G.; Piromalis, D.D.; Papadakis, G. A Novel Autonomous PV Powered Desalination System Based on a DC Microgrid Concept Incorporating Short-Term Energy Storage. Sol. Energy 2018, 159, 947–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardakani, R. Enhancing Water Purification Performance Through Reverse Osmosis at the Genaveh Combined Cycle Power Plant: A Study on Salt Rejection and Permeate Flow Rate Optimization. Iran. J. Chem. Chem. Eng. 2024, 43, 4067–4078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, C.G.; Joshi, M.; Swaminathan, J. Membrane Compaction in Batch Reverse Osmosis Operation and Its Impact on Specific Energy Consumption. Desalination 2024, 592, 118132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, B.; Wu, P.; Siesler, H.W. In Situ Study of Diffusion and Interaction of Water and Mono- or Divalent Anions in a Positively Charged Membrane Using Two-Dimensional Correlation FT-IR/Attenuated Total Reflection Spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. B 2008, 112, 2880–2887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Al-Sulaimi, S.; Farooque, A.M. Characterization of New and Fouled SWRO Membranes by ATR/FTIR Spectroscopy. Appl. Water Sci. 2018, 8, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donose, B.C.; Sukumar, S.; Pidou, M.; Poussade, Y.; Keller, J.; Gernjak, W. Effect of PH on the Ageing of Reverse Osmosis Membranes upon Exposure to Hypochlorite. Desalination 2013, 309, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, M.A.; Jaafar, J.; Ismail, A.F.; Othman, M.H.D.; Rahman, M.A. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy. In Membrane Characterization; Elsevier B.V.: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Abri, M.; Al-Ghafri, B.; Bora, T.; Dobretsov, S.; Dutta, J.; Castelletto, S.; Rosa, L.; Boretti, A. Chlorination Disadvantages and Alternative Routes for Biofouling Control in Reverse Osmosis Desalination. npj Clean Water 2019, 2, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| High pressure pump | |

| Pump type | Positive displacement, seal-less diaphragm pump |

| Model | G21XDSGSNEMG |

| Maximum flow rate | 3.1 L/min @ 1450 RPM |

| Maximum pressure | 103 bar |

| Motor Specifications | |

| Motor type | K100L-6 (Valiadis S.A., Athens, Greece) |

| Rated Power | 1.5 kW/50 Hz |

| Voltage | 3-phase, 380 V |

| VFD specifications | |

| Model | iC5 (LS Electric Co., Anyang, South Korea) |

| Type | SV022iC5-1F |

| Input voltage | 1-phase, 230 V |

| Output voltage | 3-phase, 380 V |

| Membrane active area | 20.6 cm2 |

| Maximum pressure | 69 bar |

| Maximum Temperature | 150 °C |

| Dimensions: | |

| Slot Depth | 2.28 mm |

| Slot Width | 39 mm |

| Membrane type | SW30XFR (FiltmecTM, Edina, MN, USA) |

| Feed | Seawater |

| pH range (25 °C) | 1–13 |

| Flux | 31.5 L·m−2∙h−1 at 55 bar |

| Rejection | 99.8% |

| Polymer | Polyamide TFC |

| Feed salinity | 32 kg/m3 (32,000 ppm NaCl solution) |

| Osmotic pressure | 26.19 bar |

| Feed temperature | 25 °C |

| Membrane active area | 20.6 cm2 |

| Maximum pressure | 50 bar |

| Maximum pressure during the pre-conditioning | 55 bar |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dimitriou, E.; Loukatos, D.; Arvanitis, K.G.; Papadakis, G. Experimental Evaluation of the Performance of a Flat Sheet Reverse Osmosis Membrane Under Variable and Intermittent Operation Emulating a Photovoltaic-Driven Desalination System. Water 2025, 17, 3576. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243576

Dimitriou E, Loukatos D, Arvanitis KG, Papadakis G. Experimental Evaluation of the Performance of a Flat Sheet Reverse Osmosis Membrane Under Variable and Intermittent Operation Emulating a Photovoltaic-Driven Desalination System. Water. 2025; 17(24):3576. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243576

Chicago/Turabian StyleDimitriou, Evangelos, Dimitrios Loukatos, Konstantinos G. Arvanitis, and George Papadakis. 2025. "Experimental Evaluation of the Performance of a Flat Sheet Reverse Osmosis Membrane Under Variable and Intermittent Operation Emulating a Photovoltaic-Driven Desalination System" Water 17, no. 24: 3576. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243576

APA StyleDimitriou, E., Loukatos, D., Arvanitis, K. G., & Papadakis, G. (2025). Experimental Evaluation of the Performance of a Flat Sheet Reverse Osmosis Membrane Under Variable and Intermittent Operation Emulating a Photovoltaic-Driven Desalination System. Water, 17(24), 3576. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243576