Meter-Scale Redox Stratification Drives the Restructuring of Microbial Nitrogen Cycling in Soil-Sediment Ecotone of Coal Mining Subsidence Area

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Sample Collection

2.3. Chemical Analysis

2.4. DNA Extraction and Metagenomic Sequencing

2.5. Bioinformatics Analysis

3. Result

3.1. Physicochemical Transitions Along the Subsidence Gradient

3.2. Changes in Microbial Diversity

3.3. Differentiation of Species Composition

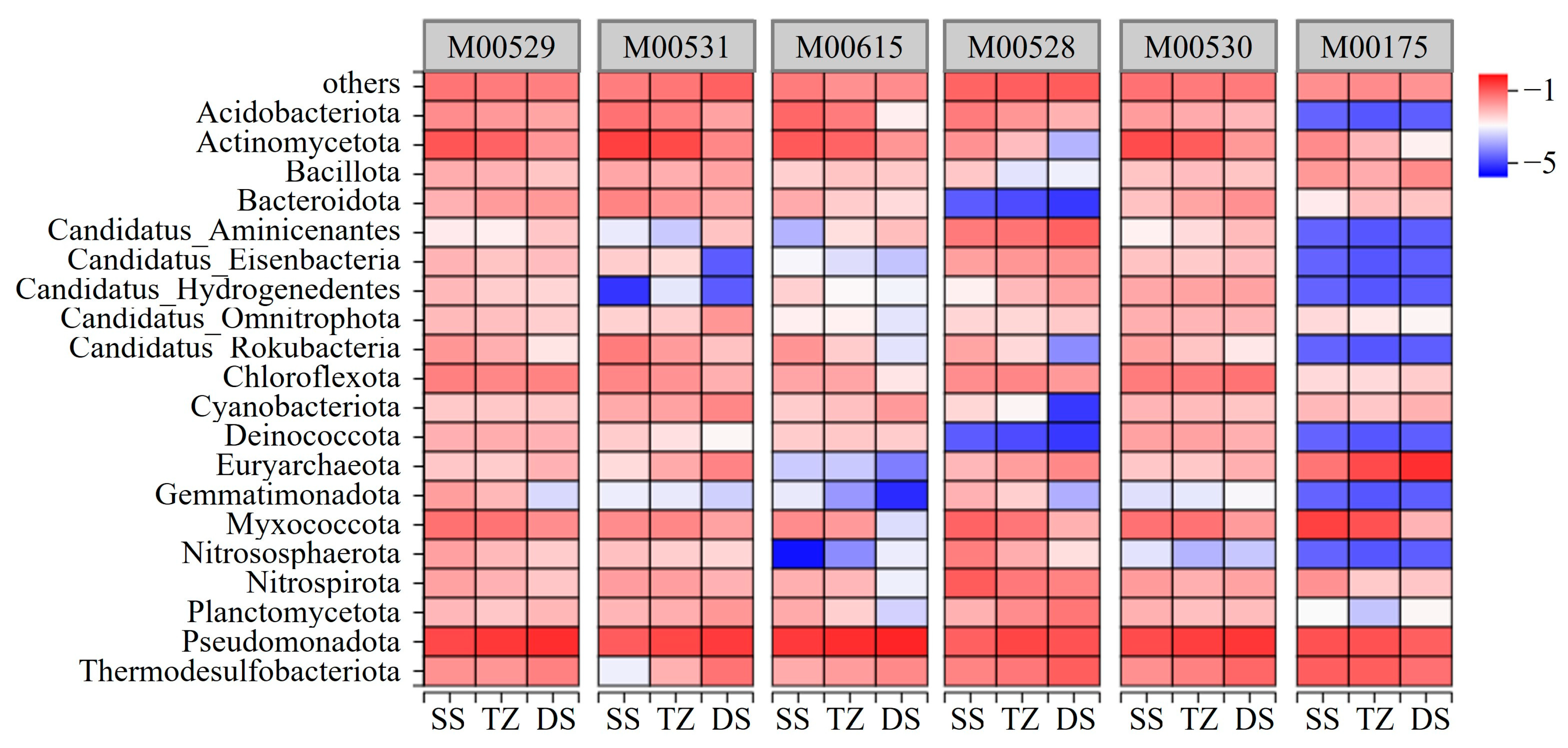

3.4. Analysis of Microbial Correlation Network at Different Subsidence Depths

3.5. Key Nitrogen Cycling Processes

4. Discussion

4.1. Changes in Microbial Community and Nitrogen Transformation Induced by Subsidence-Driven Redox Stratification

4.2. Coal Mining Subsidence Promotes Specific Rebalancing of Nitrogen Cycling Processes

4.3. Restructuring of the Co-Occurrence Network from a Densely Connected to a Modular Configuration

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, K.; Yang, K.; Wu, X.T.; Bai, L.; Zhao, J.G.; Zheng, X.H. Effects of Underground Coal Mining on Soil Spatial Water Content Distribution and Plant Growth Type in Northwest China. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 18688–18698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, E.; Guo, W.; Zhang, H.; Tan, Y.; Li, X.; Wei, Z. Degradation mechanism of cultivated land and its protection technology in the central coal-grain overlapped area of China. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 468, 143075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, Z.; Inyang, H.I.; Daniels, J.L.; Otto, F.; Struthers, S. Environmental issues from coal mining and their solutions. Min. Sci. Technol. 2010, 20, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, T.; Xiao, W.; Zhao, Y.L.; Deng, X.; Hu, Z. Identification of waterlogging in Eastern China induced by mining subsidence: A case study of Google Earth Engine time-series analysis applied to the Huainan coal field. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 242, 111742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.; Zhang, Y.; Ruan, M.; Guo, J.; Chai, T. Land Subsidence in a Coal Mining Area Reduced Soil Fertility and Led to Soil Degradation in Arid and Semi-Arid Regions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Wang, X.; Wang, R.; Liu, G. Health risk assessment of potentially harmful elements in subsidence water bodies using a Monte Carlo approach: An example from the Huainan coal mining area, China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 171, 737–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Wei, Y.; Meng, H.; Hong, J. Effects of fertilization and reclamation time on soil bacterial communities in coal mining subsidence areas. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 739, 139882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, C.; Jiang, C.; Wang, Q.; Liu, H.; Li, D.; Zhu, Q.; Liu, F. Seasonal characteristics of groundwater discharge controlled by precipitation and its environmental effects in a coal mining subsidence lake, eastern China. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 915, 170067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Shang, Z.; Wang, F.; Liang, Y.; Zou, Y.; Liu, F. Bacterial diversity in surface sediments of collapsed lakes in Huaibei, China. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 15784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, Q.; Zhao, G.; Wang, D.; Zhu, X.; Xie, L.; Zuo, D.; Wang, L.; Tian, L.; Peng, F.; Xu, B. Water periods impact the structure and metabolic potential of the nitrogen-cycling microbial communities in rivers of arid and semi-arid regions. Water Res. 2024, 267, 122472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakem, E.; Polz, M.; Follows, M. Redox-informed models of global biogeochemical cycles. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, N.; Alexander, H.; Bertrand, E.M.; Coles, V.; Dutkiewicz, S.; Leles, S. Microbial ecology to ocean carbon cycling: From genomes to numerical models. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2025, 53, 595–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birnbaum, C.; Waryszak, P.; Trevathan-Tackett, S.; Bowen, J.; Connolly, R.M.; Duarte, C.; Macreadie, P. Global review of blue carbon ecosystem microbial communities. Environ. Microbiol. 2025, 27, e70168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoliker, D.L.; Repert, D.A.; Smith, R.L.; Song, B.; Leblanc, D.R.; Mccobb, T.D.; Conaway, C.H.; Hyun, S.P.; Koh, D.C.; Moon, H.S. Hydrologic Controls on Nitrogen Cycling Processes and Functional Gene Abundance in Sediments of a Groundwater Flow-Through Lake. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 3649–3657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, F.; Qian, L.; Yu, X.; Huang, F.; Hu, R.; Su, H.; Gu, H.; Yan, Q. The vertical partitioning between denitrification and dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium of coastal mangrove sediment microbiomes. Water Res. 2024, 262, 122113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.Q.; Wu, G.P.; Chi, S.Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, C.L.; Jiang, H.L. Water level fluctuation regulated the effect of bacterial community on ecosystem multifunctionality in Poyang Lake wetland. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 373, 123965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, L.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, G.; Wu, G.Y.; Yang, Q.; Chen, Q. Microbial communities and sediment nitrogen cycle in a coastal eutrophic lake with salinity and nutrients shifted by seawater intrusion. Environ. Res. Sect. A 2023, 225, 115590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuypers, M.M.M.; Marchant, H.K.; Kartal, B. The microbial nitrogen-cycling network. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, Y.; Mise, K.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Shiratori, Y.; Senoo, K.; Itoh, H. Global soil metagenomics reveals distribution and predominance of Deltaproteobacteria in nitrogen-fixing microbiome. Microbiome 2024, 12, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Wang, X.; Cao, X.; Qi, W.; Peng, J.; Liu, H.; Qu, J. The influence of wet-to-dry season shifts on the microbial community stability and nitrogen cycle in the Poyang Lake sediment. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 903, 166036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yang, L.; Yu, S.; Ding, A.; Zuo, R.; Yang, J.; Li, X.; Wang, J. Environmental stressors altered the groundwater microbiome and nitrogen cycling: A focus on influencing mechanisms and pathways. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 905, 167004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, L.; Sun, Y.; Yue, Y.; Liu, C.; An, C.; Yang, T.; Lu, X.; Xu, Q.; Mei, J.; Liu, M.; et al. Stability of Aquatic Nitrogen Cycle Under Dramatic Changes of Water and Sediment Inflows to the Three Gorges Reservoir. GeoHealth 2022, 6, e2022GH000607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Xu, L.; Montoya, L.; Madera, M.; Hollingsworth, J.; Chen, L.; Purdom, E.; Singan, V.; Vogel, J.; Hutmacher, R.B.; et al. Co-occurrence networks reveal more complexity than community composition in resistance and resilience of microbial communities. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.P.; Yu, J.; Wang, S.Y.; Wang, X.M.; Schwark, L.; Zhu, G.B. Complete ammonia oxidization in agricultural soils: High ammonia fertilizer loss but low N2O production. Glob. Change Biol. 2023, 29, 1984–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, W.; Fan, T.; Xu, L.; Wang, S.; Wang, X.; Lu, A.; Chen, Y. Seasonal succession of microbial community co-occurrence patterns and community assembly mechanism in coal mining subsidence lakes. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1098236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Zhang, L.; Fang, W.K.; Shen, Z. Variations in bacterial community succession and assembly mechanisms with mine age across various habitats in coal mining subsidence water areas. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 948, 174822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pascoal, F.; Areosa, I.; Torgo, L.; Branco, P.; Baptista, M.S.; Lee, C.K.; Cary, S.C.; Magalhaes, C. The spatial distribution and biogeochemical drivers of nitrogen cycle genes in an Antarctic desert. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 927129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Hu, Y.; Fan, T.; Fang, W.; Liu, X.; Xu, L.; Li, B.; Wei, X. Microbial Community Structure and Co-Occurrence Patterns in Closed and Open Subsidence Lake Ecosystems. Water 2023, 15, 1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Hu, Z.; Yuan, D.; Li, P.; Feng, Z.; He, Y.; Wang, W. A new approach to increased land reclamation rate in a coal mining subsidence area: A case-study of Guqiao Coal Mine, China. Land Degrad. Dev. 2022, 33, 866–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Xing, P. Differences in the composition of archaeal communities in sediments from contrasting zones of Lake Taihu. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nayak, A.; Rahman, M.; Naidu, R.; Dhal, B.; Swain, C.; Nayak, A.; Tripathi, R.; Shahid, M.; Islam, M.; Pathak, H. Current and emerging methodologies for estimating carbon sequestration in agricultural soils: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 665, 890–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Yang, J.; He, G.; Liu, X.; Zhang, D. Characteristics of soil C:N:P stoichiometry and enzyme activities in different grassland types in Qilian Mountain nature reserve-Tibetan Plateau. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0271399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivani, I.; Degobbis, D. An optimal manual procedure for ammonia analysis in natural waters by the indophenol blue method. Water Res. 1984, 18, 1143–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K.; Petty, R. Determination of nitrate and nitrite in seawater by flow injection analysis. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1983, 28, 1260–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. fastp: An ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1754–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Liu, C.M.; Luo, R.; Sadakane, K.; Lam, T.W. MEGAHIT: An ultra-fast single-node solution for large and complex metagenomics assembly via succinct de Bruijn graph. Bioinformatics 2014, 31, 1674–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyatt, D.; Chen, G.L.; Locascio, P.F.; Land, M.L.; Larimer, F.W.; Hauser, L.J. Prodigal: Prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinform. 2010, 11, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Li, Y.; Kristiansen, K.; Wang, J. SOAP: Short oligonucleotide alignment program. Bioinformatics 2008, 24, 713–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huson, D.H.; Buchfink, B. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 59–60. [Google Scholar]

- Kajihara, K.T.; Hynson, N.A. Networks as tools for defining emergent properties of microbiomes and their stability. Microbiome 2024, 12, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dove, N.; Barnes, M.; Moreland, K.; Graham, R.; Berhe, A.; Hart, S. Depth dependence of climatic controls on soil microbial community activity and composition. ISME Commun. 2021, 1, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stegen, J.C.; Lin, X.; Konopka, A.E.; Fredrickson, J.K. Stochastic and deterministic assembly processes in subsurface microbial communities. ISME J. 2012, 6, 1653–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jrgensen, B.; Wenzhfer, F.; Egger, M.; Glud, R. Sediment oxygen consumption: Role in the global marine carbon cycle. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2022, 228, 103987. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, T.S.; Schreiner, K.M.; Smith, R.W.; Burdige, D.J.; Woodard, S.; Conley, D.J. Redox Effects on Organic Matter Storage in Coastal Sediments During the Holocene: A Biomarker/Proxy Perspective. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet Sci. 2016, 44, 295–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolders, E.; Baetens, E.; Verbeeck, M.; Nawara, S.; Diels, J.; Verdievel, M.; Peeters, B.; De Cooman, W.; Baken, S. Internal Loading and Redox Cycling of Sediment Iron Explain Reactive Phosphorus Concentrations in Lowland Rivers. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 2584–2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirol, A.P.; Morales Williams, A.M.; Braun, D.C.; Marti, C.L.; Pierson, O.E.; Wagner, K.J.; Schroth, A.W. Linking Sediment and Water Column Phosphorus Dynamics to Oxygen, Temperature, and Aeration in Shallow Eutrophic Lakes. Water Resour. Res. 2024, 60, e2023WR034813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, B.B.; Findlay, A.J.; Pellerin, A. The Biogeochemical Sulfur Cycle of Marine Sediments. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froelich, P.N.; Klinkhammer, G.P.; Bender, M.L.; Luedtke, N.A.; Heath, G.R.; Cullen, D.; Dauphin, P.; Hammond, D.; Hartman, B.; Maynard, V. Early oxidation of organic matter in pelagic sediments of the eastern equatorial Atlantic: Suboxic diagenesis. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1979, 43, 1075–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, F.; Duan, L.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Kou, X.; Wan, F.; Wang, Y. Sediment grain size regulates the biogeochemical processes of nitrate in the riparian zone by influencing nutrient concentrations and microbial abundance. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 954, 176467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard-Cerda, J.C.; Bockstiegel, M.; Muoz-Vega, E.; Knller, K.; Schüth, C.; Schulz, S. High-Resolution Monitoring and Redox-Potential-Based Solute Transport Modeling to Partition Denitrification Pathways at an Agricultural Site. ACS Environ. Sci. Technol. Water 2024, 4, 4917–4931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyte, K.Z.; Schluter, J.; Foster, K.R. The ecology of the microbiome: Networks, competition, and stability. Science 2015, 350, 663–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Meara, T.A.; Yuan, F.; Sulman, B.N.; Noyce, G.L.; Rich, R.; Thornton, P.E.; Megonigal, J.P. Developing a Redox Network for Coastal Saltmarsh Systems in the PFLOTRAN Reaction Model. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2024, 129, e2023JG007633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, H.; Ye, D.; Jiang, Q.; Cui, X.; Li, J.; Jiang, J.; Wang, L.; Lu, X. Vertical distribution of dissimilatory iron reducing communities in the sediments of Taihu Lake. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 889, 164332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, R.; Lau, M.; Vishnivetskaya, T.; Lloyd, K.G.; Onstott, T.C. Predominance of Anaerobic, Spore-Forming Bacteria in Metabolically Active Microbial Communities from Ancient Siberian Permafrost. Appl. Environ. Microb. 2019, 85, e519–e560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Chen, X.; Chen, Y.Y.; Li, C.; Ren, M.X.; Jiang, C.L.; Chen, Y.C.; An, S.K.; Xu, Y.F.; Zheng, L.G. Nitrate sources and transformations in surface water of a mining area due to intensive mining activities: Emphasis on effects on distinct subsidence waters. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 298, 113451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broman, E.; Abdelgadir, M.; Bonaglia, S.; Forsberg, S.C.; Wikstrm, J.; Gunnarsson, J.; Nascimento, F.J.A.; Sjoling, S. Long-Term Pollution Does Not Inhibit Denitrification and DNRA by Adapted Benthic Microbial Communities. Microb. Ecol. 2023, 86, 2357–2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sparacino-Watkins, C.; Stolz, J.F.; Basu, P. Nitrate and periplasmic nitrate reductases. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 676–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saghaï, A.; Hallin, S. Diversity and ecology of NrfA-dependent ammonifying microorganisms. Trends Microbiol. 2024, 32, 602–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Elrys, A.S.; Merwad, A.R.M.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, J.; Cai, Z.; Mueller, C. Global Patterns and Drivers of Soil Dissimilatory Nitrate Reduction to Ammonium. Environ. Sci. Technol. EST 2022, 56, 3791–3800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Liu, F.; Al, M.A.; Yang, Y.; Yu, H.; Li, M.; Wu, K.; Niu, M.; Wang, C.; He, Z. Nitrogen and sulfur cycling and their coupling mechanisms in eutrophic lake sediment microbiomes. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 928, 172518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, R.; Hou, D.; Zeng, S.; Wei, D.; Yu, L.; Bao, S.; Weng, S.; He, J.; Huang, Z. Sedimentary nitrogen and sulfur reduction functional-couplings interplay with the microbial community of anthropogenic shrimp culture pond ecosystem. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 830777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brune, A. Life at the oxic–anoxic interface: Microbial activities and adaptations. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2000, 24, 691–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehto, N.; Larsen, M.; Zhang, H.; Glud, R.; Davison, W. A mesocosm study of oxygen and trace metal dynamics in sediment microniches of reactive organic material. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 11369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, P.; Tang, X.; Koch, H.; Dong, X.; Hou, L.; Wang, D.; Zhao, Q.; Li, Z.; Liu, M.; Lücker, S. Unveiling unique microbial nitrogen cycling and nitrification driver in coastal Antarctica. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 3143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, A.E.; Bulseco, A.N.; Ackerman, R.; Vineis, J.H.; Bowen, J.L. Sulphide addition favours respiratory ammonification (DNRA) over complete denitrification and alters the active microbial community in salt marsh sediments. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 22, 2124–2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akimbekov, N.; Digel, I.; Tastambek, K.; Marat, A.K.; Turaliyeva, M.; Kaiyrmanova, G. Biotechnology of microorganisms from coal environments: From environmental remediation to energy production. Biology 2022, 11, 1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, C.; Cheng, L.; Li, C.; Zheng, L. A hydrochemical and multi-isotopic study of groundwater sulfate origin and contribution in the coal mining area. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 248, 114286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Jiang, Z.; Ji, G. Effect of sulfur sources on the competition between denitrification and DNRA. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 305, 119322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K.; Oshiki, M.; Ruan, C.; Morinaga, K.; Toyofuku, M.; Nomura, N.; Johnson, D.R. Denitrification in low oxic environments increases the accumulation of nitrogen oxide intermediates and modulates the evolutionary potential of microbial populations. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2024, 16, e13221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koch, H.; Van, K.; Lücker, S. Complete nitrification: Insights into the ecophysiology of comammox Nitrospira. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 103, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, H.; Zhou, M.; Wang, Y.; Hu, M.; Wen, J.; Li, S.; Bao, Y.; Zhao, J. Vertical niche differentiation of comammox Nitrospira in water-level fluctuation zone of the Three Gorges Reservoir, China. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2022, 34, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roumelis, C.; Willert, F.; Scaccia, M.; Welch, S.; Gabor, R.; Carrera, J.; Folch, A.; Salgot, M.; Sawyer, A. Water table fluctuations control nitrate and ammonium fate in coastal aquifers. Water Resour. Res. 2025, 61, e2024WR038087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, L.; Yu, X.; Gu, H.; Liu, F.; Fan, Y.; Wang, C.; He, Q.; Tian, Y.; Peng, Y.; Shu, L. Vertically stratified methane, nitrogen and sulphur cycling and coupling mechanisms in mangrove sediment microbiomes. Microbiome 2023, 11, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Wu, W.; Liang, W.; Wang, Y.; Hou, J.; Chen, Y.; Elvert, M.; Hinrichs, K.; Wang, F. Anaerobic degradation of organic carbon supports uncultured microbial populations in estuarine sediments. Microbiome 2023, 11, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.Z.; Li, P.; Liu, L.; Sun, Y.J.; Ju, W.M.; Li, Z.H. Seasonal variations of microbial communities and viral diversity in fishery-enhanced marine ranching sediments: Insights into metabolic potentials and ecological interactions. Microbiome 2024, 12, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.W.; Qing, C.; Huang, X.F.; Zeng, J.; Zheng, Y.K.; Xia, P.H. Seasonal dynamics and driving mechanisms of microbial biogenic elements cycling function, assembly process, and co-occurrence network in plateau lake sediments. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 951, 175510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Kan, J.J.; Liu, F.L.; Lian, K.Y.; Liang, Y.T.; Shao, H.B.; McMinn, A.; Wang, H.L.; Wang, M. Depth shapes microbiome assembly and network stability in the Mariana Trench. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e0211023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Metric | ZZ | TZ | DS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nodes | 196 | 196 | 198 |

| Edges | 1007 | 2443 | 656 |

| Average degree | 20.551 | 49.857 | 13.253 |

| Average weighted degree | 16.054 | 40.36 | 11.573 |

| Network diameter | 5 | 5 | 8 |

| Number of communities | 5 | 4 | 6 |

| Network density | 0.212 | 0.514 | 0.135 |

| Modularity | 0.278 | 0.112 | 0.492 |

| Average clustering coefficient | 0.576 | 0.824 | 0.658 |

| Average path length | 2.221 | 1.674 | 3.053 |

| Degree centralization | 0.304 | 0.249 | 0.171 |

| Positive cohesion | 0.519 | 0.528 | 0.497 |

| Negative cohesion | 0.481 | 0.472 | 0.503 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cao, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Cui, R.; Meng, L.; Jiang, X.; Hao, L.; Hu, Z. Meter-Scale Redox Stratification Drives the Restructuring of Microbial Nitrogen Cycling in Soil-Sediment Ecotone of Coal Mining Subsidence Area. Water 2025, 17, 3469. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243469

Cao Y, Li Y, Zhang X, Cui R, Meng L, Jiang X, Hao L, Hu Z. Meter-Scale Redox Stratification Drives the Restructuring of Microbial Nitrogen Cycling in Soil-Sediment Ecotone of Coal Mining Subsidence Area. Water. 2025; 17(24):3469. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243469

Chicago/Turabian StyleCao, Yingjia, Yuanyuan Li, Xi Zhang, Ruihao Cui, Lingtong Meng, Xuyang Jiang, Lijun Hao, and Zhenqi Hu. 2025. "Meter-Scale Redox Stratification Drives the Restructuring of Microbial Nitrogen Cycling in Soil-Sediment Ecotone of Coal Mining Subsidence Area" Water 17, no. 24: 3469. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243469

APA StyleCao, Y., Li, Y., Zhang, X., Cui, R., Meng, L., Jiang, X., Hao, L., & Hu, Z. (2025). Meter-Scale Redox Stratification Drives the Restructuring of Microbial Nitrogen Cycling in Soil-Sediment Ecotone of Coal Mining Subsidence Area. Water, 17(24), 3469. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243469